The objectives of this study were to evaluate the performance of the recently released IMMY Aspergillus galactomannan enzyme immunoassay (IMMY GM-EIA) when testing serum samples and to identify the optimal galactomannan index (GMI) positivity threshold for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis (IA). This was a retrospective case/control study, comprising 175 serum samples obtained from 131 patients, 35 of whom had probable or possible invasive fungal disease (IFD) as categorized using recently revised, internationally accepted definitions.

KEYWORDS: invasive aspergillosis, ELISA, Aspergillus diagnostics, serum, galactomannan

ABSTRACT

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the performance of the recently released IMMY Aspergillus galactomannan enzyme immunoassay (IMMY GM-EIA) when testing serum samples and to identify the optimal galactomannan index (GMI) positivity threshold for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis (IA). This was a retrospective case/control study, comprising 175 serum samples obtained from 131 patients, 35 of whom had probable or possible invasive fungal disease (IFD) as categorized using recently revised, internationally accepted definitions. The IMMY GM-EIA was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Performance parameters were determined and receiver operator characteristic analysis was used to identify an optimal GMI threshold. Concordance with the Bio-Rad Aspergillus Ag assay (Bio Rad GM-EIA) and IMMY sona Aspergillus lateral flow assay was assessed. The median GMIs generated by the IMMY GM-EIA for samples originating from probable IA/IFD cases (n = 31), possible IFD (n = 4), and control patients (n = 100) were 0.61, 0.11, and 0.14, respectively, and were comparable to those of the Bio-Rad GM-EIA (0.70, 0.04, and 0.04, respectively). Overall qualitative observed sample agreement between the IMMY GM-EIA and Bio-Rad GM-EIA was 94.7%, generating a kappa statistic of 0.820. At a GMI positivity threshold of ≥0.5, the IMMY GM-EIA had a sensitivity and specificity of 71% and 98%, respectively. Reducing the threshold to ≥0.27 generated sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 92%, respectively. The IMMY GM-EIA provides a comparable alternative to the Bio-Rad GM-EIA when testing serum samples. Further prospective, multicenter evaluations are required to confirm the optimal threshold and associated clinical performance.

INTRODUCTION

The detection of galactomannan using the Aspergillus antigen enzyme immunoassay (GM-EIA) is a well-established non-culture-based method to assist in the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis (IA). A number of meta-analyses have confirmed its utility in the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis and it is included in the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium (MSGERC) definitions for invasive fungal disease (IFD), and is recommended by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidelines (1–3). Until recently, GM-EIA testing was only available through a single manufacturer (Bio-Rad, CA, USA); however, as highlighted by meta-analysis, interlaboratory performance was heterogeneous despite a standardized testing method (4, 5). The development of alternative GM-EIAs by different manufacturers could, as a result of market forces, lead to cost savings for service users and pressure manufacturers to improve product design, procedure, and hopefully performance.

The IMMY cryptoccal antigen lateral flow assay (LFA) improved performance over the preexisting latex agglutination test by including additional antibodies targeting different serotypes where the detection was previously suboptimal (6). This approach of using multiple monoclonal antibodies was adopted by IMMY when developing their Aspergillus LFA and has the potential to provide greater sensitivity (7, 8). While the Bio-Rad GM-EIA utilizes the single rat monoclonal antibody (MAb) called EB-A2 to bind and detect galactomannan, the IMMY Aspergillus LFA has been developed to incorporate two MAbs, where one binds to a similar GM epitope as does EB-A2 and the other binds a novel target. Indeed, the LFA has been associated with excellent performance when testing respiratory samples (e.g., BAL fluid, sensitivity 83 to 92% and specificity 91 to 92%) and blood (e.g., serum, sensitivity 97% and specificity 98%) (7–9). While the LFA provides flexibility in testing, permitting both a high frequency of testing and application to low sample numbers, it cannot readily be applied to high-throughput screening of large numbers, where plate-based ELISA formats, with the potential for automation, are preferential. With this in mind, IMMY applied the same antibody combination used in the Aspergillus LFA to the ELISA format.

This study describes the first evaluation of the performance of the IMMY Aspergillus ELISA when testing serum from a large cohort of patients at risk of IA and compares it with the performances of IMMY sona Aspergillus LFA and the well-validated Bio-Rad GM-EIA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient population.

This was a retrospective, anonymous case/control study, comprising 175 serum samples taken between 2012 and 2019 for routine diagnostic investigations for IFD, with 97.1% of samples originating between 2017 and 2019. Samples were stored at −80°C for quality control and performance evaluation purposes not requiring ethical approval. Samples were selected to represent a range of galactomannan indices (GMI) as generated by the Bio-Rad GM-EIA. While Bio-Rad GM-EIA positivity is regularly associated with the presence of IA, the assay is neither 100% sensitive nor 100% specific and the GM-EIA result alone is not sufficient to confirm or exclude a diagnosis. Sample selection was performed independently from the classification of IFD. The recent second revision of the EORTC/MSGERC definitions were used to classify the certainty of IFD in each patient, using the Bio-Rad GM-EIA and/or Aspergillus PCR positivity in blood or BAL fluid as a mycological criterion when defining IA (1). In addition, probable IFD was defined in patients with host factors, clinical features typical of IFD, and positive Fungitell (1-3)-β-d-glucan (BDG) results as the mycological criterion. The IMMY GM-EIA or Aspergillus LFA result played no role when defining IA or IFD.

Routine investigations for invasive fungal disease.

As part of routine prospective diagnostic testing, samples were tested by the Bio-Rad Aspergillus Ag assay, using the EVOLIS twin plus (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, UK) by following the manufacturer’s instructions and using a positivity threshold at the time of testing of GMI ≥ 0.5. However, when using the result as a mycological criterion for defining IA, a positivity threshold of GMI ≥ 1.0 was applied. Aspergillus PCR testing was performed on serum/plasma following the recommendations of the European Aspergillus PCR initiative (now known as the Fungal PCR initiative) using a well validated “in-house” qualitative real-time PCR assay (10, 11).

The detection of BDG was performed using the Associates of Cape Cod Fungitell assay by following the manufacturer’s instructions, with a positivity threshold of 80 pg/ml. Samples were tested in duplicate and the mean value was used for interpretation, provided the coefficient of variation (COV) was less than 20%. Under circumstances where the COV was ≥20%, repeat testing was performed. Multiple (≥2) positive BDG results were used as the mycological criterion when defining IFD.

IMMY sona lateral flow assay.

The LFA was performed by following the manufacturer’s instructions, using a GMI of 0.5 as a threshold for positivity. To remove subjectivity, confirm validity, and provide a GMI, the sona LFA cube reader (IMMY Diagnostics, OK, USA) was used when reading each LFA.

IMMY Aspergillus galactomannan enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

The IMMY GM-EIA was performed manually by following the manufacturer’s instructions, utilizing the Wellwash plate washer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Basingstoke, UK) and Multiscan FC spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Basingstoke, UK). Prior to testing, all samples were heat treated with serum treatment solution for 7 min at 120°C using a heating block. Currently, given its research-use-only status, no positivity threshold is available for the IMMY GM-EIA. For clinical consistency, a GMI of 0.5 was used for comparison of performance with the LFA and the Bio-RAd GM-EIAs, and prior to receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis, performed in an attempt to define an optimal threshold.

Statistical analysis.

When determining the clinical accuracy of the IMMY GM-EIA, the positivity rate in samples originating from cases was compared to the false positivity rate in control samples. Clinical performance was determined by the construction of 2-by-2 tables to calculate sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and diagnostic odds ratio of the LFA. Given the case control study design, and artificially high incidence of probable IA/IFD (23.0%), predictive values are provided for completeness, but should be interpreted with an appreciation for the influence of disease incidence on these parameters. For each proportionate value, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and, where required, P values (Fisher’s exact test; P: 0.05) were generated to determine the significance of the differences between rates. ROC analysis was performed to determine the overall performance of the GM-EIA, and to identify an optimal positivity threshold. Qualitative agreement between the IMMY GM-EIA, IMMY LFA, and Bio-Rad GM-EIA was demonstrated through the generation of observed agreement (accuracy) and a kappa statistic. Quantitative agreement was performed by determining a Spearman correlation between the GMI calculated by pairwise comparison of the three tests. When generating agreement, the original Bio-Rad GM-EIA result was utilized, while IMMY LFA and GM-EIA testing were performed contemporaneously. Median values were compared using a Mann-Whitney t test for pairwise analysis or the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) when comparing multiple median values.

RESULTS

The study involved 27 cases of probable IA, four cases of probable IFD, four cases of possible IFD, and 100 patients with no evidence of fungal disease. Most patients (87.0%) were being treated for a hematological malignancy, the median age was 58 years, and the male/female ratio was 1.46/1 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics by diagnosis type

| Parameter |

Aspergillus diagnosisc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Probable IA/IFD (n = 31) | Possible IFD (n = 4) | NEF (n = 100) | |

| Median age | 57 | 60 | 59 |

| No. male/no. female | 1.8/1 | 1/1 | 1.4/1 |

| Hematology (%) | 68a | 100 | 92b |

| No. samples tested | 53 | 10 | 112 |

Nonhematological conditions included one renal transplant, one bilateral lung transplant in a cystic fibrosis patient, and one cardiac transplant with subsequent mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Underlying disease for 7 patients was not specified.

Nonhematological conditions included community-acquired pneumonia (n = 3), solid cancer (n = 1), pulmonary embolism with cellulitis (n = 1), chronic respiratory illness with pancreatitis (n = 1), possible chronic aspergillosis after Mycobacterium avium infection (n = 1), and chest abscess (n = 1).

IA, invasive aspergillosis; IFD, invasive fungal disease; NEF, no evidence of fungal disease.

Sample positivity rates and typical galactomannan index values across populations as generated by the individual assays.

Thirty-two (18.3%) of the 175 samples were positive (GMI ≥ 0.5) by the IMMY GM-EIA, and positivity rates for samples originating from cases (probable IA/IFD), possible IFD, and control patients were 56.6% (30/53; 95% CI, 43.3 to 69.1), 0% (0/10; 95% CI, 0.0 to 27.8), and 1.8% (2/112; 95% CI, 0.5 to 6.3), respectively. Positivity rates for samples originating from cases were significantly greater than those for samples from both possible IFD and control patients (Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.001 and P < 0.0001, respectively). The median GMIs generated by the IMMY GM-EIA for cases, possible IFD, and control samples were 0.61, 0.11, and 0.14, respectively (Table 2). The median value for case samples was significantly higher than for the others (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001).

TABLE 2.

Associated IMMY GM-EIA, IMMY sona Aspergillus LFA, and Bio-Rad GM-EIA galactomannan index values by diagnosis type

| Index value |

Aspergillus diagnosisa

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probable IA/IFD (n = 31) |

Possible IFD (n = 4) |

NEF (n = 100) |

|||||||

| IMMY GM-EIA | IMMY LFA | Bio-Rad GM-EIA | IMMY GM-EIA | IMMY LFA | Bio-Rad GM-EIA | IMMY GM-EIA | IMMY LFA | Bio-Rad GM-EIA | |

| Min. GMI | 0.11 | 0.33 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| 25% percentile GMI | 0.30 | 0.68 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.03 |

| Median GMI | 0.61 | 1.26 | 0.70 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.04 |

| 75% percentile GMI | 1.40 | 2.11 | 1.60 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.05 |

| 90% percentile GMI | 2.41 | 3.15 | 4.61 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.37 | 0.09 |

| Max. GMI | 10.60 | 8.05 | >19.98 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 1.08 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

IA, invasive aspergillosis; IFD, invasive fungal disease; NEF, no evidence of fungal disease; LFA, lateral flow assay; GM-EIA, galactomannan enzyme immunoassay; GMI, galactomannan index.

Fifty (28.6%) of the 175 samples were positive (GMI ≥ 0.5) by the IMMY LFA and positivity rates for samples originating from cases (probable IA/IFD), possible IFD, and control patients were 90.6% (48/53; 95% CI, 79.8 to 95.9), 0% (0/10; 95% CI, 0.0 to 27.8), and 1.8% (2/112; 95% CI, 0.5 to 6.3), respectively. The IMMY LFA positivity rate when testing samples from cases was significantly greater than that generated by the IMMY GM-EIA (P < 0.0001). The median GMIs generated by the IMMY LFA for cases, possible IFD, and control samples were 1.26, 0.21, and 0.17, respectively (Table 2). The median GMIs generated by the IMMY LFA when testing probable and possible IFD cases were significantly greater than that generated by the IMMY GM-EIA (P = 0.0008 and P = 0.0045, respectively).

One-hundred sixty-nine samples were also tested by the Bio-Rad GM-EIA (six samples tested by the IMMY GM-EIA were BDG-positive samples only); of these, 30 (17.8%) samples were positive (GMI ≥ 0.5). Bio-Rad GM-EIA positivity rates for samples originating from cases (probable IA/IFD), possible IFD, and control patients were 63.8% (30/47; 95% CI, 49.5 to 76.0), 0% (0/10; 95% CI, 0.0 to 27.8), and 0% (0/112; 95% CI, 0.0 to 3.3), respectively. There were no significant differences in the positivity rates generated by the IMMY and Bio-Rad GM-EIA across the different subpopulations (P > 0.5413). The median GMIs generated by the Bio-Rad GM-EIA for cases, possible IFD, and control samples were 0.70, 0.04, and 0.04, respectively (Table 2). There was no significant difference between the median GMI associated with cases when tested by the IMMY and Bio-Rad GM-EIAs (P = 0.9578), although median GMIs for controls and possible IFD were significantly lower by the Bio-RAd GM-EIA (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0028, respectively).

Sample concordance between the IMMY GM-EIA, IMMY LFA, and Bio-Rad GM-EIA.

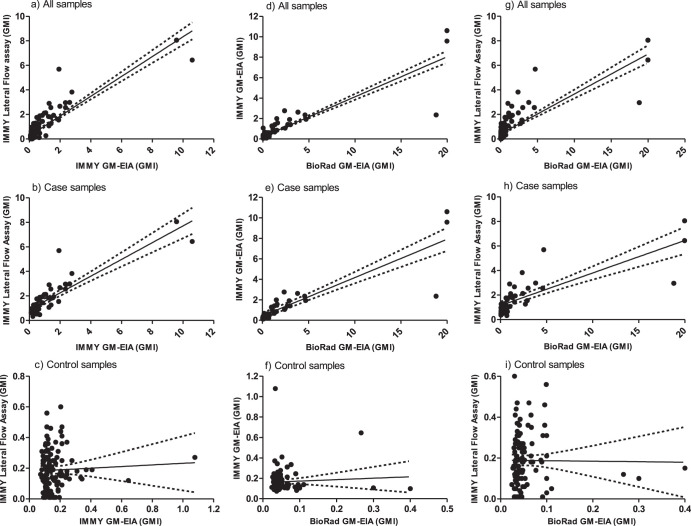

Overall qualitative observed sample agreement between the IMMY LFA and GM-EIA was 86.3% (95% CI, 80.4 to 90.6), generating a kappa statistic of 0.623 (95% CI, 0.442 to 0.805), representing good agreement. Qualitative observed agreement for samples originating from cases was 62.3% (95% CI, 48.8 to 74.1), with 95% of the discordance arising due to samples that were IMMY GM-EIA negative but positive by the LFA. Qualitative observed agreement for samples originating from controls was 96.7% (95% CI, 91.9 to 98.7). The overall quantitative correlation between the GMIs calculated by the IMMY GM-EIA and the LFA was moderate (Spearman’s coefficient = 0.57; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1a). The correlation between GMIs from samples originating from cases was very strong (Spearman’s coefficient = 0.84; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1b). There was no significant correlation between the GMIs for samples originating from the control population (Spearman’s coefficient = 0.03; P = 0.715) (Fig. 1c), although the 95th percentile values for both IMMY tests (IMMY GMI-EIA = 0.34; IMMY LFA = 0.45) were below the usual GMI positivity threshold (GMI ≥ 0.5).

FIG 1.

Linear correlation between galactomannan index (GMI) values generated by the IMMY GM-EIA, IMMY sona Aspergillus lateral flow assay (LFA), and the Bio-Rad GM-EIA when testing serum samples.

Overall qualitative observed sample agreement between the IMMY GM-EIA and Bio-Rad GM-EIA was 94.7% (95% CI, 90.2 to 97.2), generating a kappa statistic of 0.820 (95% CI, 0.706 to 0.934), representing excellent agreement. Qualitative observed agreement for samples originating from cases was 85.1% (95% CI, 72.3 to 92.6), with discordance evenly dispersed (57.1% Bio-Rad GM-EIA positive/IMMY GM-EIA negative; 42.9% Bio-Rad GM-EIA negative/IMMY GM-EIA positive). Qualitative observed agreement for samples originating from controls was 98.4% (95% CI, 94.2 to 99.6). The overall quantitative correlation between the GMIs calculated by the IMMY and the Bio-Rad GM-EIA tests was fair (Spearman’s coefficient = 0.49; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1d). The correlation between GMIs from samples originating from cases was very strong (Spearman’s coefficient = 0.91; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1e). There was no significant correlation between the GMIs for samples originating from the control population (Spearman’s coefficient = −0.16; P = 0.096) (Fig. 1f).

Overall qualitative observed sample agreement between the IMMY LFA and Bio-Rad GM-EIA was 89.9% (95% CI, 84.5 to 93.6), generating a kappa statistic of 0.712 (95% CI, 0.587 to 0.837), representing very good agreement. Qualitative observed agreement for samples originating from cases was 67.4% (95% CI, 53.0 to 79.1), with 94% of the discordance arising due to samples that were GM-EIA negative but positive by the LFA. Qualitative observed agreement for samples originating from controls was 98.4% (95% CI, 94.2 to 99.6). The overall quantitative correlation between the GMIs calculated by the Bio-Rad GM-EIA and the IMMY LFA was moderate (Spearman’s coefficient = 0.63; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1g). The correlation between GMIs from samples originating from cases was very strong (Spearman’s coefficient = 0.82; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1h). There was no significant correlation between the GMIs for samples originating from the control population (Spearman’s coefficient = 0.09; P = 0.3249) (Fig. 1i).

Clinical performance of the IMMY GM-EIA.

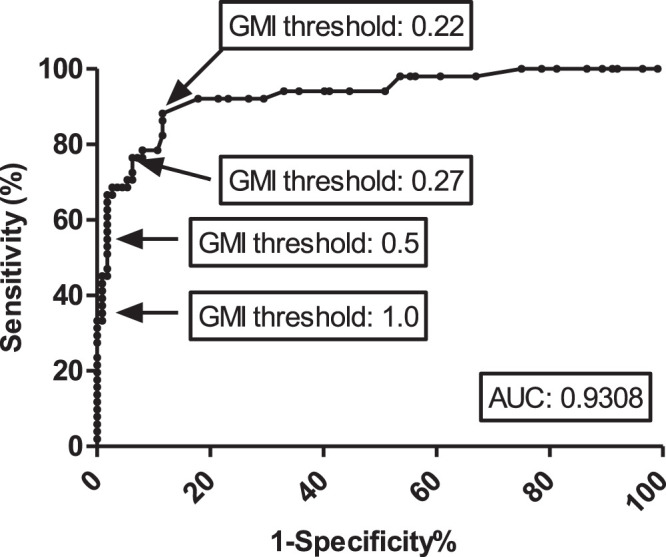

The IMMY GM-EIA performance when testing serum is shown in Table 3. At a GMI positivity threshold of ≥0.5, sensitivity and specificity were 71% and 98%, respectively, and the assay could be confidently used to confirm a diagnosis of IA (positive likelihood ratio: 35.5). Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analysis identified an optimal positivity threshold at a GMI of 0.27, where the test could be used to both confirm (positive likelihood ratio: 11.3) and exclude IA (negative likelihood ratio: 0.11) (Table 3 and Fig. 2). By lowering the threshold to 0.22, sensitivity was increased to 96.8% while maintaining a good specificity. Increasing the threshold to 1.0 provided only a minimal increase in specificity but compromised sensitivity (Table 3). The area under the ROC curve was 0.9308 (95% CI, 0.8868 to 0.9748).

TABLE 3.

Clinical performance of the IMMY GM-EIA when testing serum samples from cases with probable IA/IFD (n = 31) and control patients with no evidence of invasive fungal disease (n = 100)

| Performance parametera | Galactomannan index positivity threshold |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥0.22 | ≥0.27 | ≥0.5 | ≥1.0 | |

| % sensitivity (95% CI) | 96.8 (83.8–99.4) | 90.3 (75.1–96.7) | 71.0 (53.4–83.9) | 48.4 (32.0–65.2) |

| % specificity (95% CI) | 87.0 (79.0–92.2) | 92.0 (85.0–95.9) | 98.0 (93.0–99.5) | 99.0 (94.6–99.8) |

| % PPV (95% CI) | 69.8 (54.9–81.4) | 77.8 (61.9–88.3) | 91.7 (74.2–97.7) | 93.8 (71.7–98.9) |

| % NPV (95% CI) | 98.9 (93.8–99.8) | 96.8 (89.9–98.4) | 91.6 (83.8–94.9) | 86.1 (78.6–91.3) |

| LR +tive | 7.44 | 11.29 | 35.48 | 48.39 |

| LR −tive | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.30 | 0.52 |

| DOR | 200.77 | 107.33 | 119.78 | 92.81 |

| Youden’s statistic | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 0.47 |

IA, invasive aspergillosis; IFD, invasive fungal disease; GM-EIA, galactomannan enzyme immunoassay; CI, confidence interval; LR +tive, positive likelihood ratio; LR –tive, negative likelihood ratio; DOR, diagnostic odds ratio.

FIG 2.

Receiver operator characteristic curve of the IMMY GM-EIA when testing serum samples from cases of probable IA/IFD (n = 31) and control patients with no evidence of IFD (n = 100). When considering all samples, at a 0.5 GMI threshold the sensitivity was 54.9% and the specificity was 98.2%. Using a 0.22 GMI threshold, sensitivity was 88.2% and specificity was 88.4%. Using a 0.27 GMI threshold, sensitivity was 76.5% and specificity 92.9%. Using a 1.0 GMI threshold, sensitivity was 37.3% and specificity 99.1%. Note that these values differ from those in Table 3 as they consider all samples tested, whereas in Table 3 performance was calculated on a patient basis. IA, invasive aspergillosis; IFD, invasive fungal disease; GMI, galactomannan index; AUC, area under the curve.

DISCUSSION

This study describes the first evaluation of the IMMY GM-EIA to assist in the diagnosis of IA when testing serum samples. At the usual GMI positivity threshold of ≥0.5, the combined performance (sensitivity 71.0%; specificity 98.0%) was comparable to the meta-analytical performance of the well-established Bio-RAd GM-EIA, where pooled sensitivity and specificity were 79% and 81 to 86%, respectively, although the influence of the heterogeneity of the case population needs to be considered when interpreting sensitivity (4, 5). At this GMI threshold, the assay was excellent for confirming IA, and applying the positive likelihood ratio (35.48) to an incidence more typical of routine prospective setting (5%) generates a posttest probability of IA of 65.1% when the test is positive. Even though the negative likelihood ratio (0.3) at a threshold of ≥0.5 is not sufficient to exclude IA, when this is applied to a 5% incidence the probability of the patient having IA when the test is negative is only 1.6%. ROC analysis indicated that by using a lower GMI positivity threshold of ≥0.27, the overall assay performance could be improved through increasing sensitivity by 19.3%, while only compromising specificity by 6.0%. Using this threshold, both the positive (11.29) and negative (0.11) likelihood ratios were sufficient to confirm and exclude IA, respectively. Given the 90th percentile for GMI values from control samples tested by the IMMY GM-EIA was 0.24, assay robustness between batches of kit must be confirmed before this lower threshold can be accepted as suitable.

Lowering the threshold to ≥0.22 improved sensitivity slightly, but compromised specificity to the same degree. Nevertheless, if the IMMY GM-EIA generates a GMI of <0.22, the posttest probability of IA is 0.2%. Increasing the threshold to ≥1.0 resulted in only a minor improvement in specificity, but significantly reduced sensitivity. At this threshold the posttest probability of IA was 71.8%, which is important when considering the recent revision of the EORTC/MSGERC definitions, where the GMI threshold has been increased to 1.0 to improve confidence when defining probable cases (1).

Qualitative agreement between the IMMY and Bio-Rad GM-EIA assays was excellent across both the known cases and control populations. While the overall quantitative correlation between the assays was fair, this was driven by there being no significant correlation in the GMIs generated for samples originating from control patients. However, this was not a major cause for concern and was not significantly associated with conflicting qualitative results (2% of control samples, Fig. 1c and f), and the median GMI associated with the 95th percentile for both tests remained at <0.5 (IMMY = 0.3; Bio-Rad = 0.1). The quantitative correlation between the GMIs for case-based samples was excellent. There was no significant difference between the median GMIs generated by the IMMY and Bio-Rad GM-EIA assays when testing cases.

As seen previously when comparing the IMMY LFA with the Bio-Rad GM-EIA, the IMMY GM-EIA generated lower positivity rates and median GMI values compared to the IMMY LFA when testing cases (9). Of the four cases of probable IFD that were Bio-Rad GM-EIA negative but BDG positive, only one was positive by the IMMY GM-EIA using the ≥0.5 threshold, yet all were positive by the IMMY LFA. Given the similar bases of design of the IMMY assays, with both combining the use of two monoclonal antibodies, this is unexpected and could be a result of the limitations of the GM-EIA process that employs robust washing stages, thereby removing weakly bound antigen and reducing signal strength. Reducing the GMI threshold to ≥0.27 provides IMMY GM-EIA performance similar to that of the IMMY LFA using the ≥0.5 threshold, but a threshold reduction to ≥0.22 is required if >95% cases of probable IFD are to be detected by the IMMY GM-EIA. Using a threshold of ≥0.27 when defining positivity using the IMMY GM-EIA increased the qualitative agreement between the IMMY LFA and GM-EIAs (accuracy, 90.1%; kappa, 0.752), providing very good agreement by enhancing the detection of (6/9) cases that were missed using the higher 0.5 threshold. The Bio-Rad GM-EIA failed to detect any of the probable IFD cases even when the threshold was reduced to ≥0.22.

Ten samples from the four possible IFD cases (by definition GM-IA negative) previously reported negative by the LFA, were also negative by the IMMY GM-EIA and other biomarker assays (1-3-β-d-glucan and Aspergillus PCR) (9). While it is possible that these patients had an alternative fungal infection (e.g., Mucorales infection) or an alternative clinical reason for their chest radiology, it highlights the limitations of the EORTC/MSGERC definition of possible IA based on radiology alone, which should arguably be downgraded in the presence of multiple negative fungal biomarker assays or alternatively considered possible IFD (1).

The retrospective case/control single center design of the study is an obvious limitation. While this study design is beneficial for evaluating diseases of low incidence, such as IA, sample selection bias needs to be considered when interpreting performance. Furthermore, the artificially high incidence of disease will inevitably affect predictive values, hence the need to provide likelihood ratios. The effect of storage on assay performance need also be considered. However, agreement between the Bio-Rad and IMMY GM-EIA data were excellent (95%), and while discordance was slightly greater when testing samples from cases, conflicting positivity was distributed relatively evenly between both assays, indicating sample degradation was not a major issue. Indeed, the IMMY LFA, performed contemporaneously with IMMY-GIA, confirmed the presence of galactomannan in samples that were negative by GM-EIA testing. Further large-scale, multicenter, prospective performance evaluation is required. It would be useful to determine performance through the combination of biomarkers, but this is not feasible when the biomarkers in question are being used to define the actual cases. Subsequently, performance parameters for the other biomarker assays (BDG, Bio-Rad GM-EIA, and Aspergillus PCR) have not been included.

To conclude, the IMMY GM-EIA provides a comparable alternative to the Bio-Rad GM-EIA when testing serum samples. When using the usual ≥0.5 threshold, performance was slightly inferior to the IMMY LFA companion assay, but could be improved by lowering the threshold to ≥0.27, and the plate-based design of the assay does ease the testing of larger batches of samples, with the potential to automate the procedure. A strategy combining the IMMY GM-EIA and LFA would also permit complementary near patient testing and high-throughput screening, utilizing the same monoclonal antibodies. Further prospective, multicenter evaluations are required to confirm the optimal threshold and associated clinical performance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank IMMY for providing the kits required to perform this study at no charge.

P.L.W. has performed diagnostic evaluations and received meeting sponsorship from Bruker, Dynamiker, and Launch Diagnostics and has received speaker fees, expert advice fees, and meeting sponsorship from Gilead, speaker and expert advice fees from F2G, and speaker fees from MSD and Pfizer. P.L.W. is a founding member of the European Aspergillus PCR Initiative. M.B. has received speaker fees, expert advice fees, and meeting sponsorship from Gilead, and meeting sponsorship from AbbVie. J.S.P., R.P., and L.V. have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, Steinbach WJ, Baddley JW, Verweij PE, Clancy CJ, Wingard JR, Lockhart SR, Groll AH, Sorrell TC, Bassetti M, Akan H, Alexander BD, Andes D, Azoulay E, Bialek R, Bradsher RW, Bretagne S, Calandra T, Caliendo AM, Castagnola E, Cruciani M, Cuenca-Estrella M, Decker CF, Desai SR, Fisher B, Harrison T, Heussel CP, Jensen HE, Kibbler CC, Kontoyiannis DP, Kullberg BJ, Lagrou K, Lamoth F, Lehrnbecher T, Loeffler J, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Marchetti O, Marr KA, Masur H, Meis JF, Morrisey CO, Nucci M, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Pagano L, Patterson TF, Perfect JR, Racil Z, Roilides E, Ruhnke M, Prokop CS, Shoham S, et al. 2020. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin Infect Dis 71:1367–1376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson TF, Thompson GR 3rd, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Nguyen MH, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, Walsh TJ, Wingard JR, Young JA, Bennett JE. 2016. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 63:e1–e60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ullmann AJ, Aguado JM, Arikan-Akdagli S, Denning DW, Groll AH, Lagrou K, Lass-Flörl C, Lewis RE, Munoz P, Verweij PE, Warris A, Ader F, Akova M, Arendrup MC, Barnes RA, Beigelman-Aubry C, Blot S, Bouza E, Brüggemann RJM, Buchheidt D, Cadranel J, Castagnola E, Chakrabarti A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Dimopoulos G, Fortun J, Gangneux JP, Garbino J, Heinz WJ, Herbrecht R, Heussel CP, Kibbler CC, Klimko N, Kullberg BJ, Lange C, Lehrnbecher T, Löffler J, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Marchetti O, Meis JF, Pagano L, Ribaud P, Richardson M, Roilides E, Ruhnke M, Sanguinetti M, Sheppard DC, Sinkó J, Skiada A, Vehreschild MJGT, Viscoli C, Cornely OA. 2018. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect 24 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):e1–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leeflang MM, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Visser CE, Scholten RJ, Hooft L, Bijlmer HA, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM. 2008. Galactomannan detection for invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromized patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4:CD007394. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfeiffer CD, Fine JP, Safdar N. 2006. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis using a galactomannan assay: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 42:1417–1427. doi: 10.1086/503427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang HR, Fan LC, Rajbanshi B, Xu JF. 2015. Evaluation of a new cryptococcal antigen lateral flow immunoassay in serum, cerebrospinal fluid and urine for the diagnosis of cryptococcosis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS One 10:e0127117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lass-Flörl C, Lo Cascio G, Nucci M, Camargo Dos Santos M, Colombo AL, Vossen M, Willinger B. 2019. Respiratory specimens and the diagnostic accuracy of Aspergillus lateral flow assays (LFA-IMMY™): real-life data from a multicentre study. Clin Microbiol Infect 25:1563.e1-1563–e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mercier T, Dunbar A, de Kort E, Schauwvlieghe A, Reynders M, Guldentops E, Blijlevens NMA, Vonk AG, Rijnders B, Verweij PE, Lagrou K, Maertens J. 2020. Lateral flow assays for diagnosing invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in adult hematology patients: a comparative multicenter study. Med Mycol 58:444–452. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myz079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White PL, Price JS, Posso R, Cutlan-Vaughan M, Vale L, Backx M. 2020. Evaluation of the performance of the IMMY sona Aspergillus galactomannan lateral flow assay when testing serum to aid in the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol 58:e00053-20. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00053-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White PL, Mengoli C, Bretagne S, Cuenca-Estrella M, Finnstrom N, Klingspor L, Melchers WJG, McCulloch E, Barnes RA, Donnelly JP, Loeffler J, European Aspergillus PCR Initiative (EAPCRI). 2011. Evaluation of Aspergillus PCR protocols for testing serum specimens. J Clin Microbiol 49:3842–3848. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05316-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White PL, Linton CJ, Perry MD, Johnson EM, Barnes RA. 2006. The evolution and evaluation of a whole blood polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of invasive aspergillosis in hematology patients in a routine clinical setting. Clin Infect Dis 42:479–486. doi: 10.1086/499949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]