Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Cerebral endothelial cells (CECs) and axons of neurons interact to maintain vascular and neuronal homeostasis and axonal remodeling in normal and ischemic brain, respectively. However, the role of exosomes in the interaction of CECs and axons in brain under normal conditions and after stroke are unknown.

Methods:

Exosomes were isolated from CECs of non-ischemic rats (nCEC-exos) and ischemic rats (isCEC-exos), respectively. A multi-compartmental cell culture system was employed to separate axons from neuronal cell bodies.

Results:

Axonal application of nCEC-exos promotes axonal growth of cortical neurons, whereas isCEC-exos further enhance axonal growth than nCEC-exos. Ultrastructural analysis revealed that CEC-exos applied into distal axons were internalized by axons and reached to their parent somata. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that both nCEC-exos and isCEC-exos contain abundant mature miRNAs; however, isCEC-exos exhibit more robust elevation of select miRNAs than nCEC-exos. Mechanistically, axonal application of nCEC-exos and isCEC-exos significantly elevated miRNAs and reduced proteins in distal axons and their parent somata that are involved in inhibiting axonal outgrowth. Blockage of axonal transport suppressed isCEC-exo-altered miRNAs and proteins in somata, but not in distal axons.

Conclusion:

nCEC-exos and isCEC-exos facilitate axonal growth by altering miRNAs and their target protein profiles in recipient neurons.

Keywords: stroke, endothelial cells, exosomes, microRNA, axons

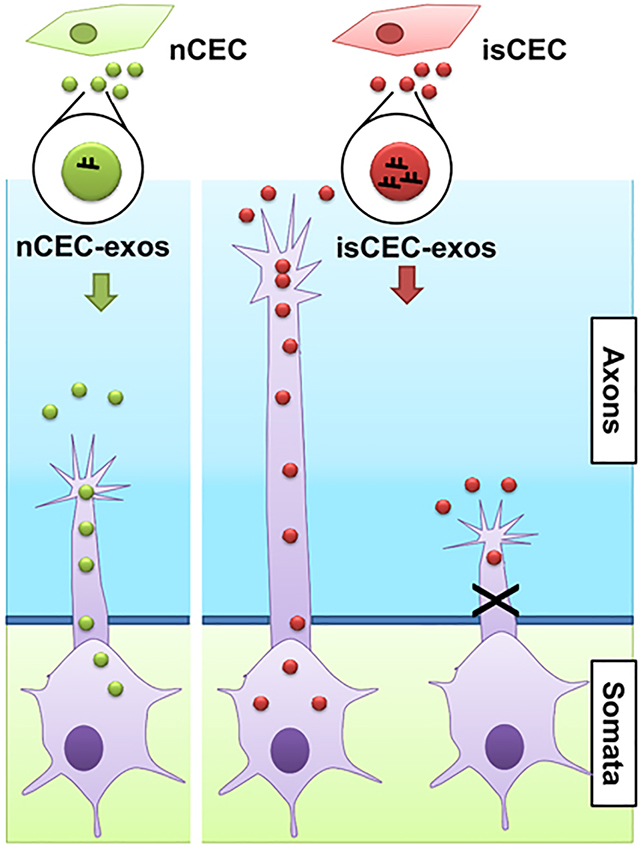

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of morbidity. Neurovascular coupling, including stroke-induced angiogenesis and axonal remodeling, is one of the key contributors to brain repair processes after stroke, which leads to spontaneous and most often incomplete functional recovery1, 2. Angiogenesis is an orchestrated process that requires a switch of relatively quiescent cerebral endothelial cells (CECs) to activated phenotype in the peri-infarct area where the survival neurons often undergo spontaneous axonal outgrowth 3, 4. Communications between stroke-activated CECs and axonal sprouting have not been fully investigated, although sprouting cerebral blood vessels and neurites share the same group of genes that guide axonal remodeling5, 6. Elucidating cellular and molecular mechanisms that underlie this communication may provide new therapeutic targets for facilitating neurovascular remodeling, consequently resulting in improvement of neurological function during stroke recovery.

Exosomes (diameter of ~30 to 100nm), small extracellular vesicles (EVs, <100nm), are nano-vesicles originating from the fusion of endosomes and multivesicular bodies (MVB) with the cell plasma membranes 7, 8. Exosomes are essential components of cell-cell communication by transferring their cargo of proteins, lipids and RNAs between source and recipient cells 9, 10. Emerging data indicate that exosomes derived from glial cells and mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) regulate neuronal function by transferring cargo of proteins and miRNAs 11–14. Fruhbeis et al demonstrated that exosomes from oligodendrocytes can be internalized by distal axons of embryonic cortical neurons and thereby improve neuronal viability under conditions of cell stress12. We have shown that exosomes derived from MSCs transfer miRNAs including the miR-17–92 cluster to distal axons of cortical neurons and promote axonal growth even in the presence of axonal inhibitory chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs)14. These data suggest that distal axons can internalize exosomes, and that transfer of exosomes miRNAs may modulate axonal function. However, it is unknown whether exosomes derived from CECs activated by stroke play a role in axonal growth.

In the present study, we employed cortical neurons cultured in a multi-compartmental culture device as a model system to investigate the effect of exosomes derived from non-ischemic and ischemic CECs (nCEC-exos and isCEC-exos, respectively) on axonal growth and on changes of endogenous miRNA profiles within recipient neurons. Our findings indicate that both nCEC-exos and isCEC-exos significantly promote axonal growth, however, isCEC-exos exhibit a more robust effect on axonal growth by modulating axonal and somal miRNAs and their target proteins that are involved in mediating axonal growth.

Methods and materials

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Henry Ford Hospital. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request. Please see supplemental materials for expanded methods.

Cortical neurons cultured in microfluidic devices

Cortical neurons were harvested from embryonic day-18 Wistar rats (Charles River), in which the sex cannot be identified, according to published protocols14, 15.

Two types of axonal microfluidic chamber devices were used: 1) Standard Device (SND450, Xona Microfluidics, Supplemental Fig. IA) 16. 2) Triple Chamber Neuron Device (TCND500, Supplemental Fig. II AB)17.

Animal model and primary culture of rat CECs

Young adult male Wistar rats (3-months old, 270–300g, Charles River) were subjected to transient (1 hour) middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) according to our published protocols18, 19. Animals were sacrificed 7 days after tMCAO when angiogenesis is at a peak 19. Male rats were employed based on data that angiogenesis in the ischemic brain has been well characterized in male, but not in female ischemic rats18, 20. CECs were isolated from non ischemic adult male rats (n=4) or rats subjected to 7 days of tMCAO (n=4), respectively, according to published protocols and more than 90 % of isolated CECs exhibited phenotypes of endothelial cells 20, 21. The CECs were cultured in CEC growth medium for 4 to 7 days when CECs reached approximately 60% confluence. Then, fetal bovine serum (FBS) was replaced with exosome depleted FBS (System Biosciences) for additional 48~72 hours. After that, the conditioned medium was collected for isolation of exosomes.

Isolation and characterization of exosomes from CECs

Exosomes were isolated from the conditioned medium according to our published protocol 22. The particle numbers and size of CEC-exos were analyzed by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) of Nanosight (NS300, Malvern Panalytical).

Ultra-structural morphology and proteins in collected exosomes were examined by means of transmission electron microscope (TEM, Phillips, EM208) and Western blotting, respectively.

Experimental protocol of axonal growth

To examine the effect of exosomes on axonal growth, exosomes were placed into the axonal compartment of the SND450 and TCND500 devices on DIV3 and DIV5, respectively, and the total length of axons and growth cone extension were measured according to our published protocols 15, 22, 23.

To analyze growth cone extension, a time-lapse microscope was employed.

To assess the effects of CSPGs and the soluble form of Sema6A (Sema6A-Fc) on axonal growth in the presence of exosomes, CSPGs at 2μg/ml23 (MilliporeSigma) or Sema6A-Fc at 10nM 24 (R&D system) along with exosomes were applied to the axonal compartment of SND450 on DIV3 for 24 hours.

To examine the effect of exosomes on axonal transport, the movement of endosomes/lysosomes labeled by lysotracker (ThermoFisher Scientific) within the axons were analyzed25.

To block the axonal transport, emetine (2μM) was added into the proximal axon compartment (Proximal Axon, Supplemental Fig. II) for 4 hours on DIV5 and then removed. After that, exosomes were added into the distal axon compartment (Distal Axon, Supplemental Fig. II). The growth cone extension was measured by means of the time-lapse microscope. The RNA and protein samples were collected accordingly at the end of experiments.

Exosome labeling and Immunogold staining

Two sets of exosomes labeling were employed. To label fresh harvested exosomes, an Exo-fect exosome transfection kit (System Bioscience, CA) was used as previously reported22. To specifically label exosomes, CEC-exos with the presence of GFP proteins (CEC-GFP-exos) were generated according to our published protocol26. To track axonal internalization of CEC-GFP-exos at the ultra-structural level, we performed immunogold staining according to our published protocol26.

Knockdown of Dicer

To examine the effect of CEC-exo cargo miRNAs on axonal growth, we transfected CECs with shRNA against Dicer. Levels of Dicer and miRNAs in dp-Dicer-exo cargo were examined by means of Western blot and qRT-PCR, respectively.

Fluorescent In situ hybridization (FISH) and Immunocytochemistry

Locked nucleic acid probes specifically against rat miR-27a, miR-19a and U6 snRNA, and scramble probes (Exiqon) were used for hybridization to detect mature miRNAs according to a published protocol 27. Immunofluorescent staining was performed and analyzed as previously described 15.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins in the cell body or in axonal compartments were extracted. Western blots were performed according to our published protocol15, 22.

miRNA PCR Array and Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction.

Total RNA in axons and cell bodies of cortical neurons or in CEC-exos was isolated using the miRNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) as reported 15, 22, 23.

MiRNA profiles were analyzed using a miRNA PCR array kit (MIRN-107ZE-1, Qiagen) 22, 23.

TaqMan miRNA assays was performed to verify miRNAs detected by the miRNA PCR array.

miScript Precursor Assay (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used to determine the precursor miRNA levels. Analysis of gene expression was carried out using the 2(−ΔΔCt) method 28.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analysis was performed using the GraphPad Prism 8 (version 8.2.1). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used when comparing more than two groups. Student’s t test was used when comparing two groups. Values presented are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A p-value < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

CEC-exos applied to distal axons promote axonal growth of cortical neurons

We first characterized EVs isolated from primary non-ischemic and ischemic cerebral endothelial cells (nCEC-exos and isCEC-exos, respectively). Our data (Supplemental Fig. III) indicate that EVs isolated from CEC supernatant are enriched with exosomes according to the MISEV 2018 guideline29 and that ischemic CECs do not alter the morphological and characteristic properties of their released exosomes.

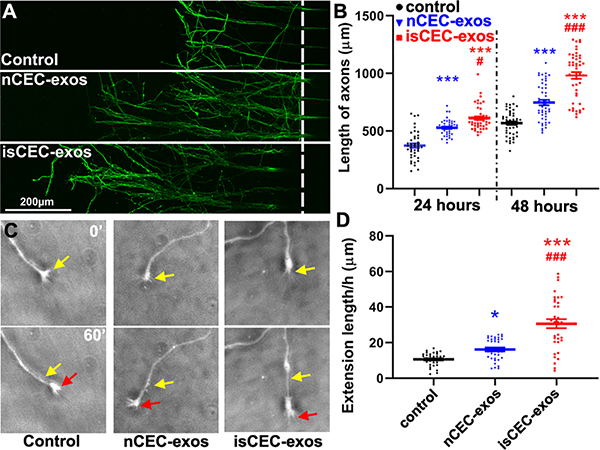

We then assessed the effects of nCEC-exos and isCEC-exos on axonal growth of cortical neurons cultured in microfluidic device SND450 (Supplemental Fig. I A). The axonal application of nCEC-exos significantly increased axonal growth in a dose dependent manner with a maximum effect at a dose of 3×107particles/mL (Supplemental Fig. I B). In addition, nCEC-exos significantly enhanced the speed of growth cone extension with leveling off at 4 hours after treatment (Supplemental Fig. I C). Compared with nCEC-exos, isCEC-exos further significantly enhanced axonal growth and growth cone extension (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. CEC-exos applied to distal axons promote axonal growth.

Representative confocal microscopic images show axonal growth at 24 hours (A) and time-lapse microscopic images of growth cone extension (C) and quantitative data of distal axonal growth at 24 hours and 48 hours (B) and growth cone extension during a 24 hours period (D), respectively. Yellow and red arrows in panel C indicate the start (0’) and end positions (60’), respectively. * p<0.05, *** p<0.001 vs control; #, p<0.05, ###, p<0.001 vs nCEC-exos.

CEC-exos applied to axons alter endogenous miRNAs and their target genes in recipient neurons

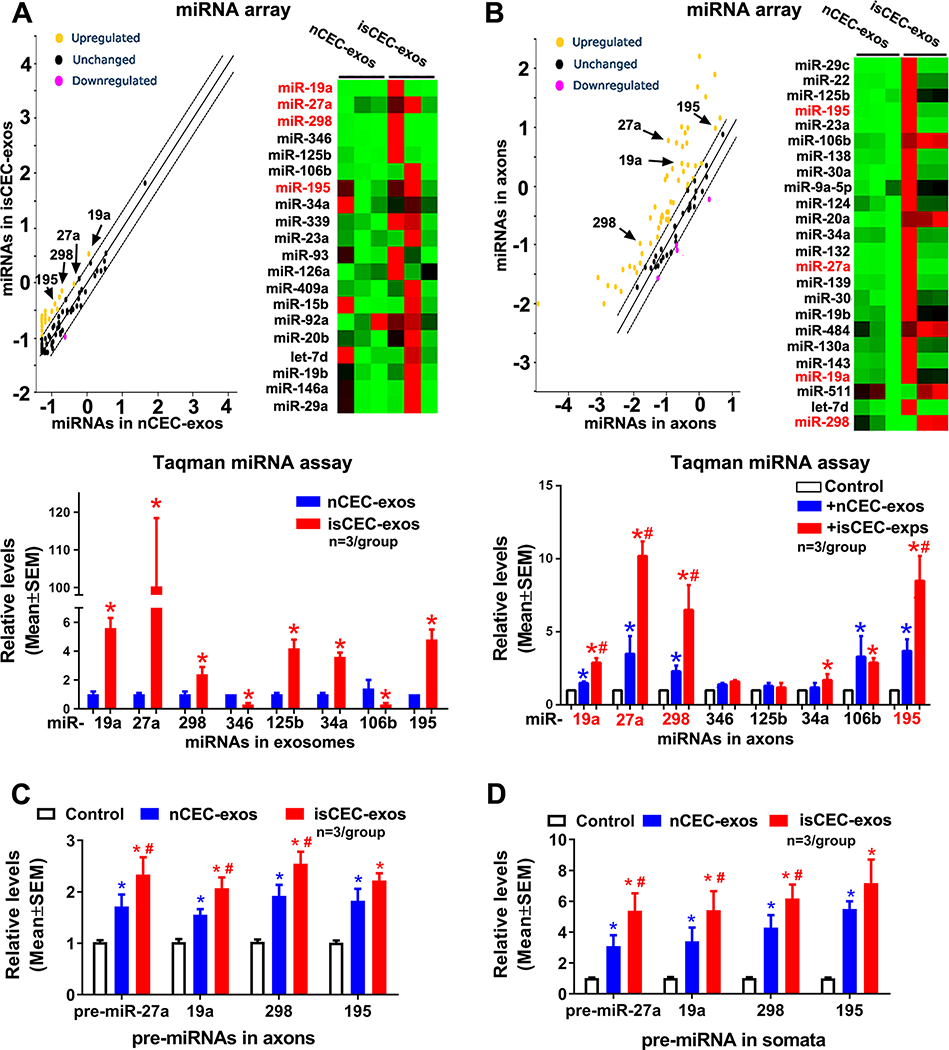

Exosomes transfer their cargo miRNAs into recipient cells and mediate cell function 30, 31. The PCR miRNA array analysis of CEC-exo cargo showed that 24 enriched miRNAs were found to be more than 2 times higher in isCEC-exos than in nCEC-exos (Fig. 2A, Supplemental Tables I–III, Supplemental Fig. IV). Taqman miRNA assay verified the levels of 6 miRNAs (miR-19a, miR-27a, miR-298, miR-125b, miR-34a, and miR-195) were significantly higher in isCEC-exos than nCEC-exos (Fig. 2A). We then examined the effect of CEC-exos on axonal miRNAs with PCR miRNA array and found that compared with non-treated axons, the 6 exosome-enriched miRNAs were among upregulated miRNAs in axons by CEC-exo treatment (Fig. 2B, Supplemental Tables IV–VI, Supplemental Fig. IV). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that compared with nCEC-exos, isCEC-exos treatment significantly increased four miRNAs (miR-19a, 27a, 298 and 195) in axons, while miR-34a and miR-125b did not significantly increase (Fig. 2B). FISH analysis further verified isCEC-exos substantially increased miR-27a and miR-19a in axons and growth cones (Supplemental Fig. V A). These data indicate that the increased four miRNAs in axons were associated with their enrichment within CEC-exos.

Figure 2. The effect of CEC-exos on levels of mature and precursor miRNAs and miRNA machinery proteins of cortical neurons.

Scatter plot and heatmap of miRNA PCR array data demonstrate the differential miRNAs in exosomes (A, upper), and the differential miRNAs in axons after axonal application of CEC-exos (B, upper). Quantitative RT-PCR data show the mature miRNAs in exosomes (A, lower), mature (B, lower) and precursor miRNAs (C) in axons and mature miRNAs in somata (D) after the axonal application of CEC-exos,. respectively. *, p<0.05 vs nCEC-exos in A, vs control in B-D; #, p<0.05 vs nCEC-exos in B-D. The heatmap images only listed partial miRNAs and please view all miRNAs measured in Supplemental Figure IV.

It is possible that the augmented miRNAs could be endogenously induced by axons of neurons upon CEC-exos uptake, rather than transferred by CEC-exos. Mature miRNAs are derived from Dicer-cleaved precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNA), while Dicer and pre-miRNAs are present in distal axons of neurons15, 32. We thus examined pre-miRNA levels of the four miRNAs within CEC-exos and in axons and somata of cortical neurons. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis did not detect these 4 pre-miRNAs within nCEC-exos and isCEC-exos (Supplemental Table VII). However, application of nCEC-exos into the axonal compartment for 4 hours increased the levels of 4 pre-miRNAs in distal axons and their parent somata, with more robust elevation of these pre-miRNAs in samples collected from the cell body compartment (Fig. 2C) than in samples from the axon compartment (Fig. 2D). Compared with nCEC-exos, isCEC-exos further elevated these pre-miRNAs in axons and their somata (Fig. 2C, D). Moreover, nCEC-exos and isCEC-exos significantly increased mature forms of these four miRNAs in the cell bodies (Supplemental Fig. V B). Western blotting analysis showed that application of CEC-exos into the axonal compartment for 4 hours did not alter the levels of Dicer and Ago2 in distal axons and in their parent somata, suggesting that CEC-exos did not affect levels of the miRNA synthesis machinery proteins (Supplemental Fig. V C). Collectively, these data suggest that in addition to transferring their cargo miRNAs to recipient neurons, CEC-exos applied into the distal axons trigger endogenous miRNA synthesis in the somata of cortical neurons, leading to increased pre- and mature miRNAs.

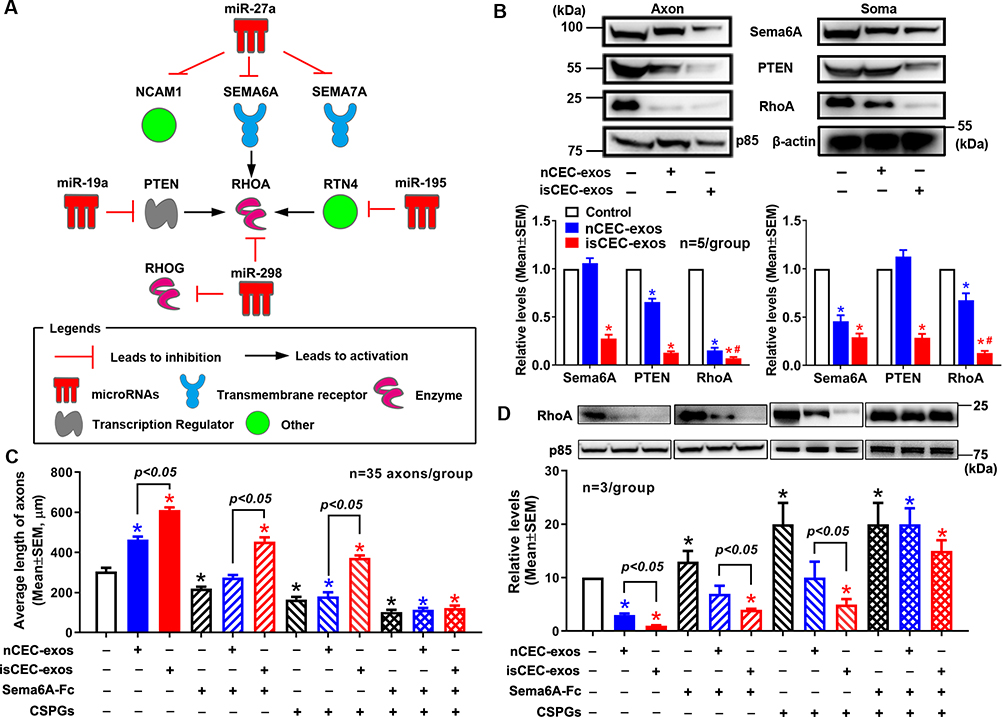

Axonal miRNAs regulate axonal growth by locally modulating protein composition15, 23, 33. We thus performed bioinformatics analysis by means of Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA), which revealed a network of miR-27a, −19a, −298 and −195 and their putative target genes (Fig. 3A) that include well-known axon-inhibitory proteins, Sema6A, PTEN, and RhoA15, 34–36. Western blotting analysis showed that treatment of axons with nCEC-exos or isCEC-exos reduced neuronal levels of PTEN, RhoA, and Sema6A in axons and somata, whereas treatment with isCEC-exos induced a significantly greater reduction of these proteins than treatment with nCEC-exos (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that the CEC-exos-elevated the four miRNAs could potentially target genes encoding these axonal inhibitory proteins in axons and somata. We thus examined whether CEC-exosomal cargo miRNAs contribute to the effect of CEC-exos on axonal growth. CEC-exos isolated from CECs transfected with shRNA against Dicer (dp-Dicer-exos) had a broad reduction of Dicer-related miRNAs compared to cargo miRNAs of CEC-exos derived from CECs transfected with control shRNAs (con-exos, Supplemental Fig. VI AB). Treatment of axons with dp-Dicer-exos did not significantly enhance axonal growth (Supplemental Fig. VI C), indicating that CEC-exo cargo miRNAs are required for promoted axonal growth.

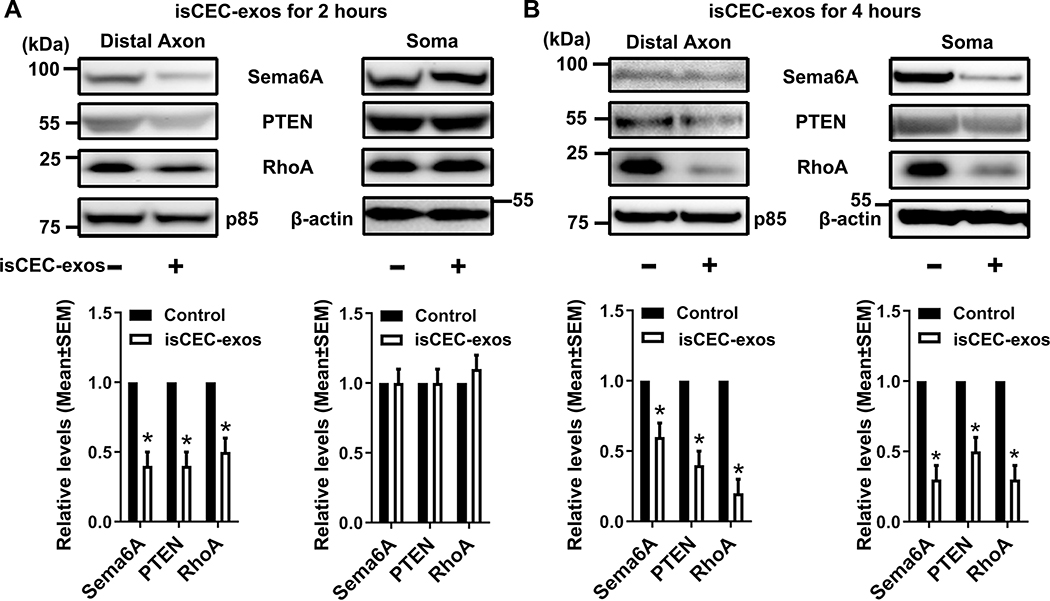

Figure 3. The effect of CEC-exos on levels of proteins in cortical neurons.

A miRNA/target genes network generated by IPA (A). Representative Western blot images and quantitative data (B, n=5/group) show axonal application of nCEC- or isCEC-exos on levels of Sema6A, PTEN, RhoA in distal axons (Axon) and cell bodies (Soma). Quantitative data of axon length (C), representative Western blot images and their quantitative data (D) show axonal application of Sema6A-Fc or CSPGs in the presence or absence of nCEC-exos or isCEC-exos, respectively, on axonal growth (C) and the axonal levels of RhoA (D). * p<0.05 vs control; #, p<0.05 vs nCEC-exos.

RhoA is a center node among genes in the miRNA/target network (Fig. 3A). We thus further examined the effect of RhoA on CEC-exo-enhanced axonal growth. Application of nCEC-exos into the axonal compartment in the presence of CSGPs that are known to activate RhoA37 in axons abolished nCEC-exo-augmented axonal growth, which was associated with an increase of RhoA (Fig. 3CD). Moreover, soluble Sema6A-Fc also inhibited nCEC-exo-enhanced axonal growth and increased RhoA protein (Fig. 3CD). However, individually adding CSPGs or soluble Sema6A-Fc into the axonal compartment did not significantly affect isCEC-exo-augmented axonal growth and did not alter isCEC-exo-reduced RhoA, although CSPGs or soluble Sema6A-Fc by themselves significantly inhibited axonal growth and increased RhoA (Fig. 3CD). In contrast, when they were added together, CSPGs and soluble Sema6A-Fc blocked isCEC-exo-enhanced axonal growth and significantly increased RhoA (Fig. 3CD). These data suggest that reduction of RhoA is critical to nCEC-exo- and isCEC-exo-enhanced axonal growth.

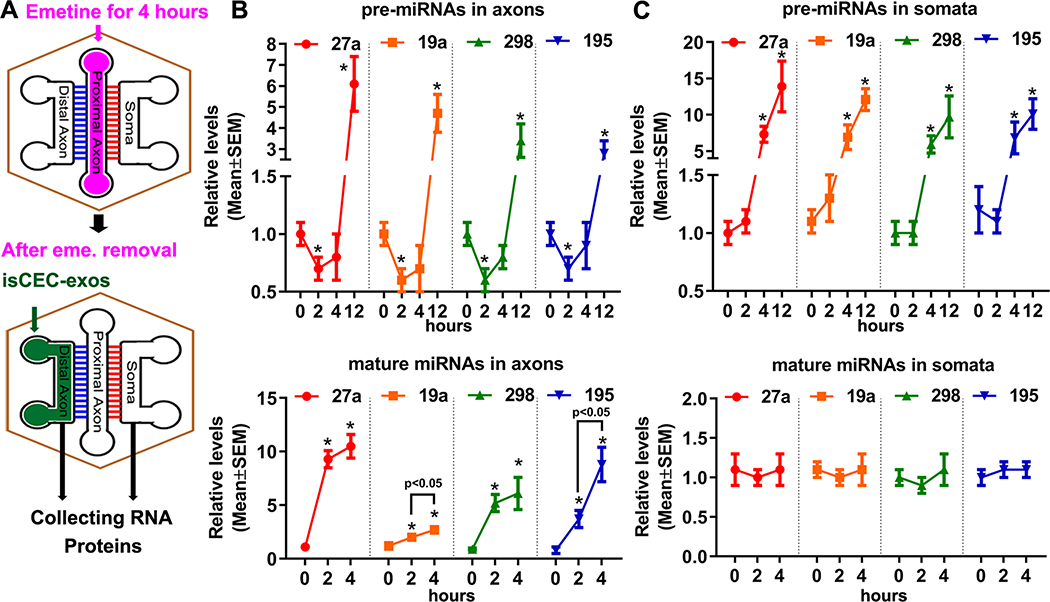

Axonal transport contributes to axon-applied CEC-exo-induced endogenous miRNA regulation

Aforementioned data that pre-miRNAs and mature miRNAs in axons and somata increased by axonal application of CEC-exos suggest that there is a communication between distal axons and their parent somata. To examine the effect of CEC-exos on this communication, a triple-compartment device (TCND500) was employed (Supplemental Fig. II AB). We found axonal application of nCEC-exos promotes axonal transport. However, the isCEC-exos exhibited further enhancement of axonal transport than nCEC-exos (Supplemental Fig. II). Emetine is a global protein synthesis inhibitor and has been widely used to study axonal transport 38, 39. Transient application of emetine alone for 4h to the proximal axon compartment inhibited bidirectional axonal transport up to 4 hours (Supplemental Fig. VII). We thus assessed whether transient blockage of axonal transport affects the endogenous miRNA expression induced by isCEC-exos. isCEC-exos applied into distal axons after emetine removal (Fig. 4A) for 2 hours did not significantly increase the selected pre-miRNAs in distal axons and somata (Fig. 4BC). In contrast, levels of mature miRNAs in the distal axons were significantly increased at 2 hours after isCEC-exos treatment (Fig. 4B, lower), whereas levels of these mature miRNAs in the somata did not significantly change (Fig. 4C, lower). These data suggest that blockage of axonal transport between distal axons and their parent cell bodies affects pre-miRNA, but not mature miRNA levels in distal axons altered by isCEC-exos. However, 4 hours after the isCEC-exos application, a significant augmentation of pre-miRNAs was detected in somata (Fig. 4C, upper), but not in distal axons (Fig. 4B, upper). By 12 hours, these pre-miRNAs were significantly elevated in both distal axons (Fig. 4B, upper) and somata (Fig. 4C, upper). Western blot analysis showed that when isCEC-exos were applied into the distal axon for 2 hours after emetine removal (Fig. 5A), isCEC-exos reduced protein levels of Sema6A, PTEN, and RhoA only in distal axons, but did not alter these protein levels in somata (Fig. 5A). At 4 hours, significant decreases of Sema6A, PTEN, and RhoA proteins were detected in both distal axons and somata (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, we found transient application of emetine alone significantly decreased the speed of axonal growth in the distal axon compartment, which gradually recovered 12 hours after removing emetine (Supplemental Fig. VIII). Application of isCEC-exos in distal axons after emetine removal did not significantly increase axonal growth until application for 4 hours (Supplemental Fig. VIII). Transient application of emetine alone to the proximal axon compartment did not significantly change levels of pre-miRNAs and mature miRNAs in the distal axon and cell body compartments (Supplemental Fig. IX). These data suggest that a network of miRNAs and proteins regulated by CEC-exos in recipient neurons is involved in CEC-exos-enhanced axonal growth, which likely occurs via a communication between distal axons and their parent somata.

Figure 4. The transient blockage of axonal transport on isCEC-exo-altered miRNAs in cortical neurons.

A schematic (A) shows a workflow of collecting samples in distal axons and somata in TCND500 after transient proximal axonal application of emetine and followed distal axonal application of isCEC-exos. Quantitative RT-PCR data show levels of selected precursor (upper panels) and mature (lower panels) miRNAs in the distal axons (B) and somata (C) after the distal axonal application of isCEC-exos for 0, 2, 4 and 12 hours, respectively, following emetine removal. * p<0.05 vs control.

Figure 5. The transient blockage of axonal transport on isCEC-exo-altered proteins in cortical neurons.

Representative Western blot images and quantitative data show the levels of Sema6A, PTEN, RhoA in distal axons (Distal Axon) and cell bodies (Soma) after the distal axon application of isCEC-exos for 2 hours (A) or 4 hours (B), respectively, following emetine removal. * p<0.05 vs control.

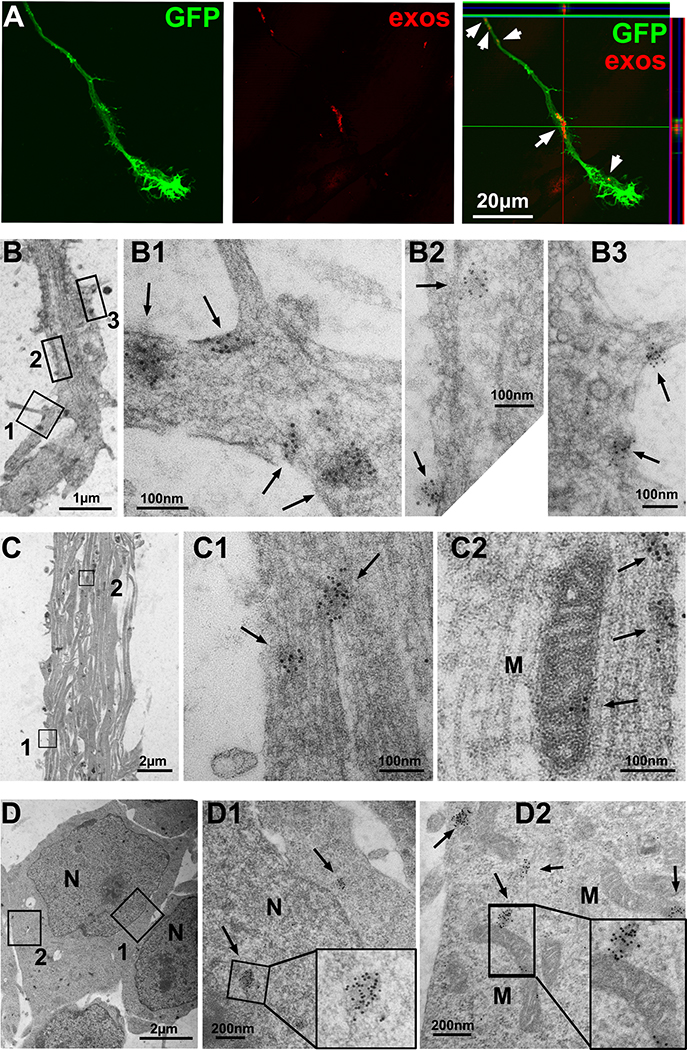

CEC-exos are internalized by distal axon and reach to parental cell bodies

To examine whether CEC-exos are internalized by axons, we imaged Texas-red labeled nCEC-exos applied to the axonal compartment. Confocal microscopic images showed red fluorescent signals were detected within GFP positive axons and growth cones (Fig. 6A), suggesting the axonal internalization of nCEC-exos.

Figure 6. Axonal application of CEC-exos are internalized by axons and reach to their parent cell bodies.

Confocal microscopic images show the internalization of Texas-red labeled nCEC-exos in axons and growth cone (exos, white arrows). Representative TEM images show the presence of GFP positive gold particles (black arrows) in axonal growth cone in the axonal compartment (B), axon bundles in microgrooves (C) and neuronal cell bodies in the soma compartment (D). M, mitochondria; N, nucleus.

To further examine whether exogenous CEC-exos are internalized by axons and reach to their parent cell bodies, we generated GFP carrying CEC-GFP-exos (Supplemental Fig. X) and applied CEC-GFP-exos into the axonal compartment for 4 hours. TEM analysis revealed GFP positive gold particles within neurofilaments and mitochondria of the treated axons (Fig. 6B,C), whereas GFP-gold particles were not detected when the primary antibody against GFP was omitted (Supplemental Fig. XI), indicating that CEC-exos are internalized by axons. Moreover, GFP positive gold particles were also detected in cytoplasm and nucleus of neuronal cell bodies (Fig. 6D), suggesting that CEC-exos internalized by axons reach to their parent cell bodies.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that exosomes derived from non-ischemic and ischemic CECs enhanced axonal growth. More importantly, the CEC-exos internalized by distal axons triggered upregulation of miRNAs, which was associated with targeted reduction of axonal inhibitory proteins in recipient neurons. These novel data suggest that CECs released exosomes play an important role in mediating axonal homeostasis and axonal plasticity under physiological and ischemic conditions, respectively. This is so particularly in light of the fact that activated CECs contributes to improvement of neurological function, while axonal remodeling in ischemic brain is required for stroke recovery40, 41.

The dynamic interaction between CECs and neurons in the neurovascular unit plays an essential role in the maintenance of brain homeostasis42, 43. Exosomes mediate communication among brain cells that include neurons, glia and blood vessel cells44–46. CECs release exosomes47, 48; however, how the endothelial-derived exosomes communicate with brain parenchymal cells, in particular with neurons, remains unknown. The present in vitro study provides evidence that exosomes derived from non-ischemic endothelial cells promote axonal growth. Furthermore, exosomes derived from ischemic endothelial cells have a more robust effect on promoting axonal growth. Limited axonal growth has been demonstrated in peri-infarct regions after stroke1, 49. We previously demonstrated that primary CECs isolated from the ischemic brain exhibit distinct RNA and protein profiles and angiogenic activity compared with CECs harvested from non-ischemic brain, although the isCECs were cultured under the normoxia condition20. The present findings suggest that isCEC-exos contribute to axonal remodeling in ischemic brain. In addition to axons, our data show that CEC-exos internalized by distal axons reached to their cell bodies, suggesting that CEC-exos could affect dendritic plasticity, which warrants further investigation. Together, data from the present study and others suggest that in addition to factors released by CECs, the endothelial generated exosomes mediate neuronal function, and that administration of CEC-exos could potentially enhance neuronal remodeling in ischemic brain.

Exosomes mediate intercellular communication by transferring their cargo including proteins and miRNAs between source and recipient cells and consequently regulate biological function of recipient cells9, 10. Emerging data indicate that exosomes affect axonal function by delivering their cargo30, 50; however, there are few studies that investigate how exosomal cargo alters gene and protein profiles that eventually determine biological function of recipient neurons. Stroke alters miRNA expression in CECs51, 52, but it remains unknown whether stroke changes miRNA profiles in CEC-exos. Using multiple approaches, the present study suggests that exosomes internalized by distal axons regulate a network of miRNA/target locally in distal axons and remotely in their cell bodies, which impact axonal growth. We first demonstrated that CEC-exos were rapidly internalized by distal axons, which led to elevation of CEC-exo-enriched mature miRNAs, initially in the distal axons and later in somata, indicating that CEC-exos elevate axonal miRNAs. We then showed that in addition to mature miRNAs, precursors of mature miRNAs were increased in somata and distal axons. Precursor miRNAs are synthesized in the nucleus and are then exported to cytoplasm where they are processed into mature miRNAs by Dicer 32, 53. Since CEC-exos only contained mature miRNAs, elevated pre-miRNAs are likely transported anterogradely from neuronal cell bodies to the axons. Indeed, our ultrastructural data showed that CEC-exos were internalized by distal axons and reached the cytoplasm and nucleus of neuronal cells, which provide strong evidence to support that the CEC-exo-cargo regulates miRNA expression in recipient neurons. Moreover, transient blocking of axonal transport resulted in reduction of pre-miRNA levels in distal axons, while resuming transiently blocked axonal transport led to elevation of pre-miRNAs in distal axons treated with CEC-exos. In addition, pre-miRNAs and Dicer were present in distal axons, whereas CEC-exos only contained mature miRNAs. Augmentation of mature miRNAs and reduction of pre-mRNAs in distal axons by CEC-exos under conditions of axonal transport blockage suggest that increased mature miRNAs either from CEC-exos and/or from preexisting pre-miRNAs in the axon that have been locally converted into mature miRNAs by Dicer. Studies have shown that multivesicular bodies (MVB) and mitochondria regulate axonal transport54–56. Our ultrastructural imaging data showed that nCEC-exos were localized to mitochondria of axons after axonal internalization (Fig. 6). Thus, the roles of MVB and mitochondria in mediating CEC-exos altered axonal transport warrant further investigation.

Selectively increased miRNAs in distal axons and their cell bodies were inversely related to their target gene encoded proteins, Sema6A, PTEN and RhoA. These proteins have been demonstrated as intrinsically inhibitory proteins within neurons that suppress axonal growth35, 36, 57. We and others have reported that the CSGPs activate RhoA in axons, leading to inhibition of axonal growth, and that inhibition of RhoA increases the regeneration of axons37, 58. Using CSPGs and Sema6A-Fc that activate RhoA, the present study suggests that reduction of RhoA plays an important role in mediating CEC-exos-enhanced axonal growth. Others have shown that suppression of axonal miR-338 leads to augmentation of mRNA and protein in one of its target genes, mitochondrial cytochrome c cxidase IV, in axons and somata as early as 4 hours after transfecting59. Collectively, the present study suggests that in addition to transferring cargo miRNAs, CEC-exos regulate endogenous miRNAs and their putative target protein profiles in recipient neurons, leading to CEC-exo-enhanced axonal growth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Maria Ericsson from The Harvard Medical School Electron Microscopy Facility for the guidance and assistance on TEM sample processing and imaging.

Source of Funding: This work was supported by the NIH grants, R01 NS111801 (ZGZ), and American Heart Association 16SDG29860003 (YZ).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CECs

cerebral endothelial cells

- MVBs

multivesicular bodies

- MSCs

mesenchymal stromal cells

- CSPGs

chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans

- nCEC-exos

exosomes derived from non-ischemic CECs

- isCEC-exos

exosomes derived from ischemic CECs

- NTA

nanoparticle tracking analysis

- MCAO

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- FISH

fluorescent in situ hybridization

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Disclosures: None

Supplemental Materials: Expanded Materials & Methods, Online Figures I – XI, Online Tables I–VII.

References:

- 1.Yiu G, He Z. Glial inhibition of cns axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:617–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohab JJ, Fleming S, Blesch A, Carmichael ST. A neurovascular niche for neurogenesis after stroke. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13007–13016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Risau W Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature. 1997;386:671–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krupinski J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Wang JM. Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1994;25:1794–1798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Font MA, Arboix A, Krupinski J. Angiogenesis, neurogenesis and neuroplasticity in ischemic stroke. Current cardiology reviews. 2010;6:238–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klagsbrun M, Eichmann A. A role for axon guidance receptors and ligands in blood vessel development and tumor angiogenesis. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 2005;16:535–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: Composition, biogenesis and function. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2002;2:569–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colombo M, Raposo G, Thery C. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tkach M, Thery C. Communication by extracellular vesicles: Where we are and where we need to go. Cell. 2016;164:1226–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pegtel DM, Cosmopoulos K, Thorley-Lawson DA, van Eijndhoven MA, Hopmans ES, Lindenberg JL, de Gruijl TD, Wurdinger T, Middeldorp JM. Functional delivery of viral mirnas via exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6328–6333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Verrilli MA, Picou F, Court FA. Schwann cell-derived exosomes enhance axonal regeneration in the peripheral nervous system. Glia. 2013;61:1795–1806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fruhbeis C, Frohlich D, Kuo WP, Amphornrat J, Thilemann S, Saab AS, Kirchhoff F, Mobius W, Goebbels S, Nave KA, et al. Neurotransmitter-triggered transfer of exosomes mediates oligodendrocyte-neuron communication. PLoS Biol. 2013;11:e1001604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xin H, Katakowski M, Wang F, Qian JY, Liu XS, Ali MM, Buller B, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Microrna cluster mir-17–92 cluster in exosomes enhance neuroplasticity and functional recovery after stroke in rats. Stroke. 2017;48:747–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Liu XS, Katakowski M, Wang X, Tian X, Wu D, Zhang ZG. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal cells promote axonal growth of cortical neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:2659–2673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Ueno Y, Liu XS, Buller B, Wang X, Chopp M, Zhang ZG. The microrna-17–92 cluster enhances axonal outgrowth in embryonic cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6885–6894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor AM, Blurton-Jones M, Rhee SW, Cribbs DH, Cotman CW, Jeon NL. A microfluidic culture platform for cns axonal injury, regeneration and transport. Nat Methods. 2005;2:599–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villarin JM, McCurdy EP, Martinez JC, Hengst U. Local synthesis of dynein cofactors matches retrograde transport to acutely changing demands. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang ZG, Zhang L, Jiang Q, Zhang R, Davies K, Powers C, Bruggen N, Chopp M. Vegf enhances angiogenesis and promotes blood-brain barrier leakage in the ischemic brain. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:829–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang R, Wang L, Zhang L, Chen J, Zhu Z, Zhang Z, Chopp M. Nitric oxide enhances angiogenesis via the synthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor and cgmp after stroke in the rat. Circ Res. 2003;92:308–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teng H, Zhang ZG, Wang L, Zhang RL, Zhang L, Morris D, Gregg SR, Wu Z, Jiang A, Lu M, et al. Coupling of angiogenesis and neurogenesis in cultured endothelial cells and neural progenitor cells after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:764–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Z, Hofman FM, Zlokovic BV. A simple method for isolation and characterization of mouse brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;130:53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Liu XS, Katakowski M, Wang X, Tian X, Wu D, Zhang ZG. Exosomes derived from mesenchymal stromal cells promote axonal growth of cortical neurons. Mol Neurobiol. 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Liu X, Kassis H, Wang X, Li C, An G, Gang Zhang Z. Micrornas in the axon locally mediate the effects of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans and cgmp on axonal growth. Dev Neurobiol. 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu XM, Fisher DA, Zhou L, White FA, Ng S, Snider WD, Luo Y. The transmembrane protein semaphorin 6a repels embryonic sympathetic axons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2638–2648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castle MJ, Perlson E, Holzbaur EL, Wolfe JH. Long-distance axonal transport of aav9 is driven by dynein and kinesin-2 and is trafficked in a highly motile rab7-positive compartment. Mol Ther. 2014;22:554–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang L, Chopp M, Szalad A, Lu X, Zhang Y, Wang X, Cepparulo P, Lu M, Li C, Zhang ZG. Exosomes derived from schwann cells ameliorate peripheral neuropathy in type 2 diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2020;69:749–759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pena JT, Sohn-Lee C, Rouhanifard SH, Ludwig J, Hafner M, Mihailovic A, Lim C, Holoch D, Berninger P, Zavolan M, et al. Mirna in situ hybridization in formaldehyde and edc-fixed tissues. Nat Methods. 2009;6:139–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative pcr and the 2(-delta delta c(t)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thery C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, Antoniou A, Arab T, Archer F, Atkin-Smith GK, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (misev2018): A position statement of the international society for extracellular vesicles and update of the misev2014 guidelines. Journal of extracellular vesicles. 2018;7:1535750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Exosomes in stroke pathogenesis and therapy. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:1190–1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou Y, Tian T, Zhu Y, Jaffar Ali D, Hu F, Qi Y, Sun B, Xiao Z. Exosomes transfer among different species cells and mediating mirnas delivery. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118:4267–4274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microrna biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:509–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dajas-Bailador F, Bonev B, Garcez P, Stanley P, Guillemot F, Papalopulu N. Microrna-9 regulates axon extension and branching by targeting map1b in mouse cortical neurons. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15:697–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Urbich C, Kaluza D, Fromel T, Knau A, Bennewitz K, Boon RA, Bonauer A, Doebele C, Boeckel JN, Hergenreider E, et al. Microrna-27a/b controls endothelial cell repulsion and angiogenesis by targeting semaphorin 6a. Blood. 2012;119:1607–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohtake Y, Hayat U, Li S. Pten inhibition and axon regeneration and neural repair. Neural regeneration research. 2015;10:1363–1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker BA, Ji SJ, Jaffrey SR. Intra-axonal translation of rhoa promotes axon growth inhibition by cspg. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:14442–14447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Chopp M, Liu XS, Kassis H, Wang X, Li C, An G, Zhang ZG. Micrornas in the axon locally mediate the effects of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans and cgmp on axonal growth. Dev Neurobiol. 2015;75:1402–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilley J, Coleman MP. Endogenous nmnat2 is an essential survival factor for maintenance of healthy axons. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koyuncu OO, Perlman DH, Enquist LW. Efficient retrograde transport of pseudorabies virus within neurons requires local protein synthesis in axons. Cell host & microbe. 2013;13:54–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chopp M, Zhang ZG, Jiang Q. Neurogenesis, angiogenesis, and mri indices of functional recovery from stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:827–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang ZG, Buller B, Chopp M. Exosomes - beyond stem cells for restorative therapy in stroke and neurological injury. Nature reviews. Neurology. 2019;15:193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banerjee S, Bhat MA. Neuron-glial interactions in blood-brain barrier formation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:235–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiss N, Miller F, Cazaubon S, Couraud PO. The blood-brain barrier in brain homeostasis and neurological diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:842–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Von Bartheld CS, Altick AL. Multivesicular bodies in neurons: Distribution, protein content, and trafficking functions. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93:313–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fruhbeis C, Frohlich D, Kuo WP, Kramer-Albers EM. Extracellular vesicles as mediators of neuron-glia communication. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dozio V, Sanchez JC. Characterisation of extracellular vesicle-subsets derived from brain endothelial cells and analysis of their protein cargo modulation after tnf exposure. Journal of extracellular vesicles. 2017;6:1302705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andras IE, Toborek M. Extracellular vesicles of the blood-brain barrier. Tissue barriers. 2016;4:e1131804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang J, Guo R, Yang Y, Jacobs B, Chen S, Iwuchukwu I, Gaines KJ, Chen Y, Simman R, Lv G, et al. The novel methods for analysis of exosomes released from endothelial cells and endothelial progenitor cells. Stem cells international. 2016;2016:2639728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang ZG, Chopp M. Promoting brain remodeling to aid in stroke recovery. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:543–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fruhbeis C, Frohlich D, Kramer-Albers EM. Emerging roles of exosomes in neuron-glia communication. Front Physiol. 2012;3:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma F, Sun P, Zhang X, Hamblin MH, Yin KJ. Endothelium-targeted deletion of the mir-15a/16–1 cluster ameliorates blood-brain barrier dysfunction in ischemic stroke. Sci Signal. 2020;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pan J, Qu M, Li Y, Wang L, Zhang L, Wang Y, Tang Y, Tian HL, Zhang Z, Yang GY. Microrna-126–3p/−5p overexpression attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in a mouse model of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2020;51:619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Macfarlane LA, Murphy PR. Microrna: Biogenesis, function and role in cancer. Curr Genomics. 2010;11:537–561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hollenbeck PJ, Saxton WM. The axonal transport of mitochondria. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:5411–5419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ye M, Lehigh KM, Ginty DD. Multivesicular bodies mediate long-range retrograde ngf-trka signaling. Elife. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maday S, Twelvetrees AE, Moughamian AJ, Holzbaur EL. Axonal transport: Cargo-specific mechanisms of motility and regulation. Neuron. 2014;84:292–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shim SO, Cafferty WB, Schmidt EC, Kim BG, Fujisawa H, Strittmatter SM. Plexina2 limits recovery from corticospinal axotomy by mediating oligodendrocyte-derived sema6a growth inhibition. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2012;50:193–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walker BA, Ji SJ, Jaffrey SR. Intra-axonal translation of rhoa promotes axon growth inhibition by cspg. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14442–14447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aschrafi A, Schwechter AD, Mameza MG, Natera-Naranjo O, Gioio AE, Kaplan BB. Microrna-338 regulates local cytochrome c oxidase iv mrna levels and oxidative phosphorylation in the axons of sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12581–12590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.