Abstract

Background:

Weight bias against persons with obesity impairs health care delivery and utilization and contributes to poorer health outcomes. Despite rising rates of pet obesity (including among dogs), the potential for weight bias in veterinary settings has not been examined.

Subjects/Methods:

In two online, 2×2 experimental studies, the effects of dog and owner body weight on perceptions and treatment recommendations were investigated in 205 practicing veterinarians (Study 1) and 103 veterinary students (Study 2). In both studies, participants were randomly assigned to view one of four vignettes of a dog and owners with varying weight statuses (lean vs. obesity). Dependent measures included emotion/liking ratings toward the dog and owners; perceived causes of the dog’s weight; and treatment recommendations and compliance expectations. Other clinical practices, such as terms to describe excess weight in dogs, were also assessed.

Results:

Veterinarians and students both reported feeling more blame, frustration, and disgust toward dogs with obesity and their owners than toward lean dogs and their owners (p values<0.001). Interactions between dog and owner body weight emerged for perceived causes of obesity, such that owners with obesity were perceived as causing the dog with obesity’s weight, while lean owners were perceived as causing the lean dog’s weight. Participants were pessimistic about treatment compliance from owners of the dog with obesity, and weight loss treatment was recommended for the dog with obesity when presenting with a medical condition ambiguous in its relationship to weight. Veterinarians and students also reported use of stigmatizing terms to describe excess weight in dogs.

Conclusions:

Findings from this investigation, with replication, have implications for training and practice guidelines in veterinary medicine.

Keywords: Obesity, pet care, veterinary medicine, weight bias, weight stigma

Introduction

Increases in obesity and its associated health comorbidities have necessitated enhanced training for health professionals to meet patients’ weight management needs (1). Prior studies have demonstrated that healthcare practitioners report negative attitudes toward patients with obesity and endorse factors such as willpower and “personal responsibility” as causes of obesity more strongly than they endorse biological or environmental factors (2). Obesity may also affect the number of tests ordered by physicians, and physicians attribute health problems to patients’ weight even when they are ostensibly unrelated (3,4). In addition, patients who perceive being judged by their health professionals report avoiding preventive and follow-up care services (4). To address weight bias in health care, and consequently enhance treatment utilization and patient-centered care, several professional societies have undertaken initiatives to promote awareness of weight bias among practitioners and to prevent the stigmatization of patients with obesity (1,5,6). For example, increased attention to the terms used to describe patients’ weight and the use of “people-first” language have been promoted to reduce weight stigma (7,8). Calls for more education about the etiology and treatment of obesity have also come from multiple health professions (9).

Surprisingly, the topic of weight bias has not been investigated among veterinarians. Estimates suggest that overweight/obesity affects over half of pets, including up to 60% of dogs (10–12). Similar to humans, dogs with obesity are at heightened risk for metabolic and osteoarthritic diseases (10). Dogs with obesity may also be subject to weight stigmatization. In addition, their owners may experience “courtesy stigma,” in which they are viewed negatively and blamed for their dog’s weight, as has been observed in attitudes toward parents of children with obesity (13,14). Given prior evidence that perceived weight stigma among humans in medical settings interferes with patient care (4), investigating the potential presence of weight bias in veterinary interactions may have important implications for pet health care.

The present research represents a first effort to explore potential weight bias in veterinarians. Specifically, the current two studies investigated how dog and owner body weight may impact veterinarians’ emotional responses to dogs and owners, perceived causes of and blame for dogs’ weight, and treatment recommendations and compliance expectations. Veterinarians were predicted to respond more positively to lean dogs and owners than to those with obesity, with particularly negative responses when both the owners and dog had obesity. Exploratory analyses assessed other aspects of clinical practice, such as the terms used by veterinarians to describe dogs with obesity. These aims were tested in an experimental, online study of practicing veterinarians and in an additional replication study of veterinary students.

Study 1

Methods

Participants.

Alumni from a single veterinary school were recruited by email to participate in a 10-minute voluntary, anonymous online survey. The recruitment target was 120 participants (n=30 per condition, described below), based on anticipated medium to large effect sizes (15–17) Emails were sent over the span of a few weeks. Of the 290 alumni who entered the survey, 205 veterinarians completed at least the first block of items and were included in the analyses. Table 1 presents participants’ demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Variable | Veterinarians (N=205) M±SD or N (%) |

Veterinary Students

(N=103) M±SD or N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 145 (70.7) | 82 (79.6) |

| Male | 55 (26.8) | 13 (12.6) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 143 (69.8) | 81 (78.6) |

| Male | 55 (26.8) | 13 (12.6) |

| Other | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 193 (94.1) | 84 (81.6) |

| Black or African American | 0 (0) | 2 (1.9) |

| Asian | 2 (1.0) | 5 (4.9) |

| Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Caribbean Islander, Other, or Multiracial | 3 (1.5) | 5 (4.8) |

| Hispanic and/or Latinx | 4 (2.0) | 6 (5.8) |

| Age (years) | 48.3±14.8 | 25.4±2.7 |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 25.0±5.0 | 23.4±3.6 |

| Self-Identified Weight Status (1–7) | 4.5±0.9 | 4.2±0.9 |

| Years Since Graduation | N/A | |

| Within 5 years | 37 (18.1) | - |

| 6–10 years ago | 27 (13.2) | - |

| More than 10 years ago | 133 (64.9) | - |

| Year in School | N/A | |

| Year 1 | - | 20 (19.4) |

| Year 2 | - | 19 (18.4) |

| Year 3 | - | 33 (32.0) |

| Year 4 | - | 23 (22.3) |

| Year 5 or more | - | 1 (1.0) |

Note. Participant characteristic data were missing for 5 veterinarians and 7 students. M=Mean; SD=Standard Deviation

Procedures.

The first page of the survey was the informed consent form, and participants had to click a box to provide consent before proceeding to the survey. Participants were then asked to indicate if they were a practicing veterinarian. Eligible participants were randomized via Qualtrics software to view one of four potential images featuring: a lean dog and lean owners (one male and one female owner); a lean dog and owners with obesity; a dog with obesity and lean owners; or a dog and owners with obesity. Owner images featured cartoon men and women with no faces and generic clothing. These images were identical except for weight status. The dog images were from a veterinary guide for assessing weight status and pictured the dog from the side and above. Dog and owner images were combined using Photoshop CC, with the owners standing behind the dog. Participants completed all measures and received a debriefing statement upon completion. No compensation was given for participation. This study was granted exemption by the institutional review board and was preregistered in the Open Science Framework.

Measures.

As a manipulation check, participants rated the weight status of the dog and owners (1=very underweight to 7=very overweight) (18). Positive regard toward dogs and owners was assessed by asking participants to rate (1–7) the extent to which they felt the following emotions in response to the dog and owners, respectively: affection; blame; compassion; frustration; disgust; respect; and contempt. These emotion ratings have been used in prior studies of weight bias (and general bias) in humans (19,20). Participants also rated how much they liked the dog and owners (1–7). To assess perceived causes of the dog’s body weight, an 18-item scale (items rated 1–7) was adapted, in consultation with a veterinarian, from prior weight bias scales used to measure the extent to which weight in humans is attributed to biology/genetics, behaviors, personal responsibility (e.g., motivation), and the environment (21). Participants also rated (1–7) the extent to which they believed, overall, the owners’ weight affected the dog’s weight and vice versa.

Participants were asked to endorse (yes/no) up to 7 treatment recommendations related to the dog’s weight (weight loss, reduce portion sizes, reduce treats, increase physical activity, medication for weight, follow-up visit in 2–3 weeks, or no weight loss recommendations). Treatment options also included a recommendation for a prescribed maximum number of treats per day (scored continuously). Participants rated how likely they thought owners were to comply with their treatment recommendations and how much they would want to continue to treat the dog (ratings 1–7). Participants were then informed, in a hypothetical vignette, that the dog they viewed was presenting at their clinic with respiratory problems. Participants were asked to endorse (yes/no) four potential diagnostic procedures (physical exam, scoping, chest film, or no diagnostic action). Participants were then told that the dog was diagnosed with a collapsed trachea and asked to endorse five potential treatment options (weight loss, stents, medication, surgery, or no treatment).

Participants were also provided a list of potential terms to label a dog with excess weight and asked to indicate whether they had ever used any of the terms with clients and/or colleagues (and could write in additional terms used). Finally, participants were asked whether (and how frequently) they had recommended that owners seek weight loss counseling for themselves and whether or not they would recommend obesity to be labeled as a disease in dogs.

Demographic characteristics included participant age, race/ethnicity, sex and gender, self-reported height, weight, and weight status (rated 1 [very underweight] to 7 [very overweight]), and how long ago participants graduated from veterinary school.

Analytic plan.

Factor analysis with varimax rotation and eigenvalue cutoff of 1 was conducted to group causes of dog’s weight into causal categories with item loadings>0.5. Item ratings within each grouping were averaged to create causal category scores. Data were checked to meet assumptions of normality, and dependent variables were transformed as needed. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to test the main and interacting effects of dog and owner body weight on emotions/liking toward the dog and owners and perceived causes of the dog’s weight. Logistic regression was used to identify effects of dog and owner body weight on treatment recommendations. Family-wise Bonferroni-type corrections were used to conservatively account for the large number of comparisons by dividing 0.05 by the number of comparisons per family of outcome measure (emotions/liking toward dogs, emotions/liking toward owners, perceived causes of dog’s weight, and treatment recommendations/expectations). Descriptive statistics were computed for terms used to describe excess weight in dogs, counseling of owners to seek weight management, and support for obesity to be labeled as a disease.

Results

Manipulation check.

Participants rated the dog with obesity as having a significantly higher weight status than the lean dog (6.4 vs. 4.1 on 1–7 scale, p<0.001). Similarly, owners with obesity were rated as having a significantly higher weight status than lean owners (6.1 vs. 4.0, p<0.001). No significant interaction of dog and owners’ weight was found.

Emotions and liking.

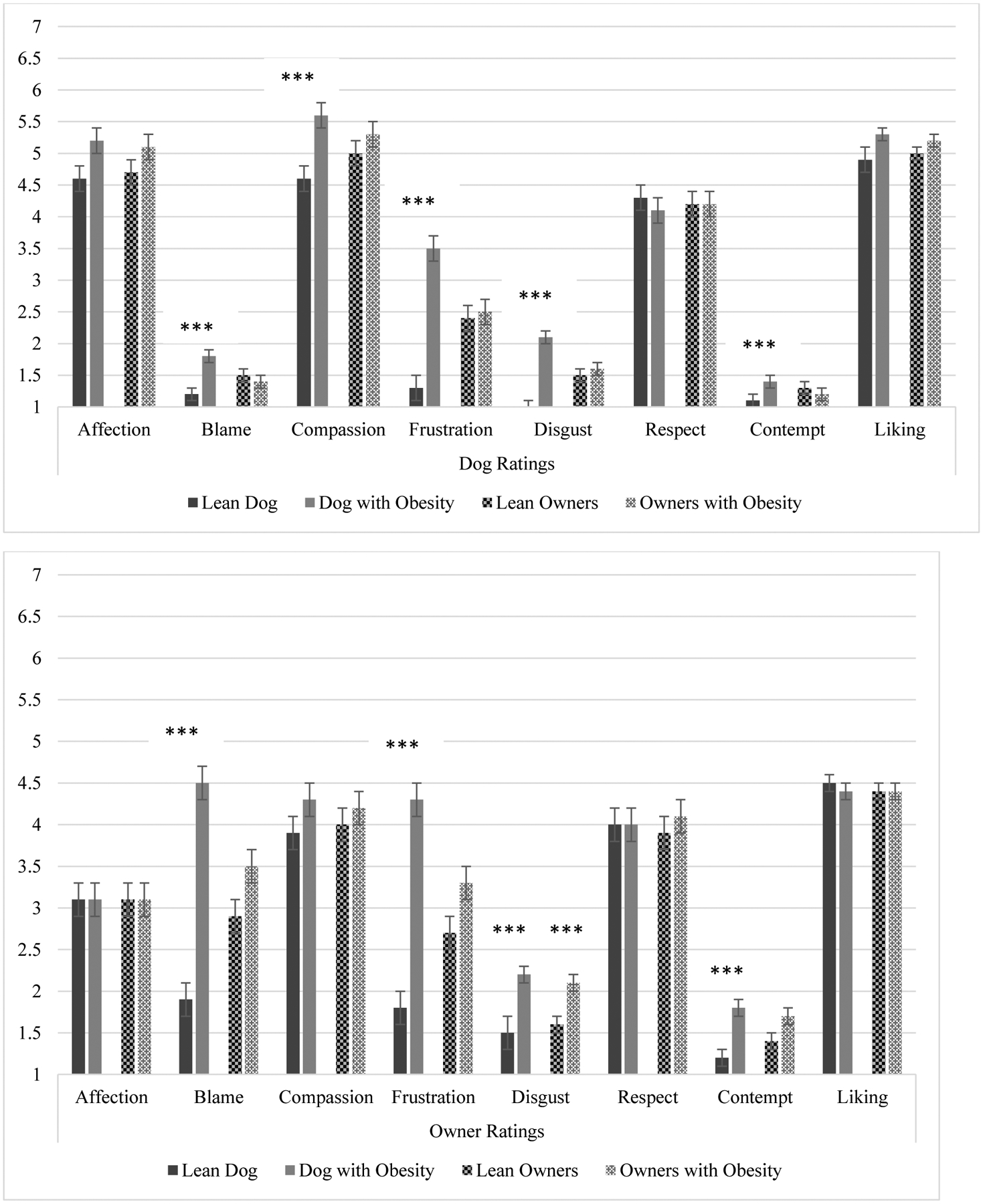

To account for the total comparisons made across emotion/liking ratings of dogs and of owners, respectively, p≤0.002 was used as the cutoff for significance for each family of comparisons.1 Figures 1a and 1b present mean emotion and liking ratings toward dogs and owners. Comparison statistics can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1.

Veterinarian Ratings of Emotions and Liking

Figure 1a. Main effects of dog and owner weight on ratings of dogs, ***p≤0.001

Figure 1b. Main effects of dog and owner weight on ratings of owners, ***p≤0.001

Note. The solid bars depict the main effects of the dog’s weight (lean versus obesity), regardless of the owners’ weight, on emotion and liking ratings. The patterned bars depict the main effects of the owners’ weight (lean versus obesity), regardless of the dog’s weight, on emotion and liking ratings.

Main effects of dog (but not owner) weight emerged for all emotion ratings toward dogs, with the exception of affection (p=0.01) and respect (p=0.42). The dog with obesity, compared to the lean dog, elicited stronger feelings of blame, frustration, disgust, and contempt toward the dog, as well as greater ratings of compassion (all p values≤0.001; Figure 1a). Main effects of owners’ weight and interaction terms of dog and owners’ weight were not significant for any emotion ratings toward the dog. No significant effects of dog or owners’ body weight were found for liking of the dog.

Similar effects were found for emotion ratings toward owners (Figure 1b). The dog with obesity elicited greater blame, frustration, disgust, and contempt toward the owners than did the lean dog (ps<0.001). Veterinarians reported more disgust toward owners with obesity than toward lean owners, although ratings were low overall. Main effects were not significant for liking of the owners, and no interaction effects of dog and owner weight were significant.

Causes of weight.

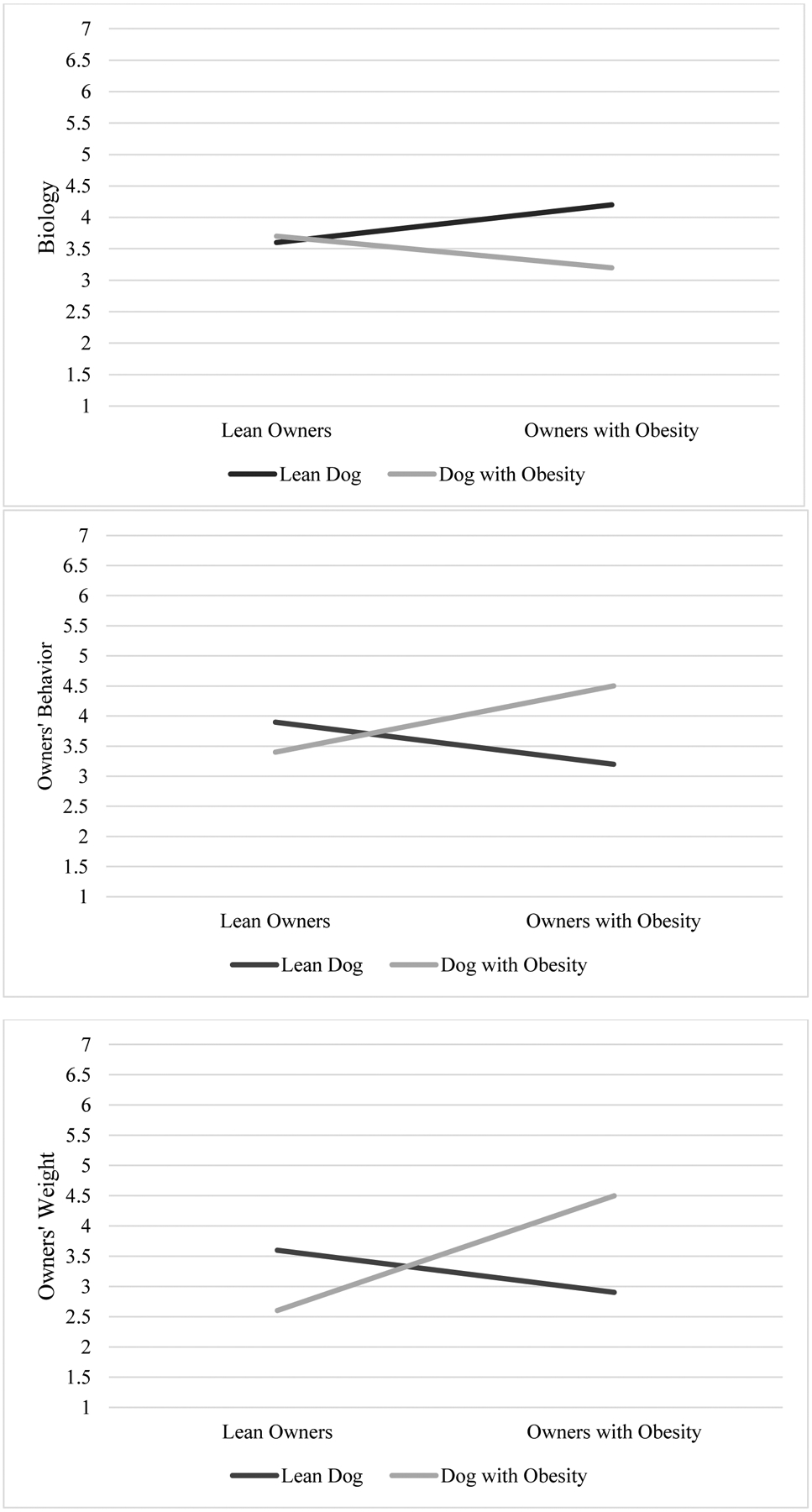

Factor analysis results produced five causal categories: biology (breed, age, genetics); dog behavior (treats, portions, physical activity); owner behavior (owners’ relationship to food, health habits); owner responsibility (owners’ level of responsibility, commitment, motivation); and environment (neighborhood safety, access to outdoor space, children in the home, other animals in the home, dog history of food deprivation) (items for owner nutrition knowledge and finances did not load onto any factor and were excluded). To account for the total comparisons across causal attribution categories and ratings of dog/owner weight affecting one another, statistical significance was set at p≤0.002.

Mean ratings of causal factors are displayed in Table S2. Significant interactions emerged for biology and owner behavior (see Figures 2a and 2b for simple slopes). When the owners had obesity, participants attributed the dog with obesity’s weight less to biology and more to owner behavior than they did for the lean dog’s weight. No effects of dog body weight were found when the owners were lean (i.e., dogs with and without obesity were perceived to have equivalent causes of weight when the owner was lean). A significant interaction of dog and owner weight also emerged for perceptions of the degree to which, in general, the owners’ weight affected the dog’s weight. Participants perceived the lean owners’ weight as having less of an effect on the dog with obesity’s weight than on the lean dog’s weight. Conversely, participants reported that the owners with obesity’s weight had more of an effect on the dog with obesity’s weight than on the lean dog’s weight (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Interaction effects of dog and owner body weight on perceived causes of dog weight among veterinarians

Figure 2a. Interaction effects for biology as a cause of dog’s weight

Figure 2b. Interaction effects for owners’ behavior as a cause of dog’s weight

Figure 2c. Interaction effects for owners’ weight as a cause of dog’s weight

Note. Interaction term for Figure 2a: F(1,201)=9.95, p=0.002; Effects of dog weight for lean owners F(1,99)=0.02, p=0.88, and owners with obesity F(1,102)=19.90, p<0.001. Interaction term for Figure 2b: F(1,201)=17.88, p<0.001; Effects of dog weight for lean owners F(1,99)=3.19, p=0.08, and owners with obesity F(1,102)=16.96, p<0.001. Interaction term for Figure 2c: F(1,201)=38.92, p<0.001; Effects of dog weight for lean owners F(1,99)=11.55, p=0.001, and owners with obesity F(1,102)=29.61, p<0.001.

Treatment recommendations.

To account for the total comparisons tested for treatment recommendations/expectations, the significance level was set at p≤0.001. The dog with obesity, compared to the lean dog, elicited more treatment recommendations to reduce portion sizes (OR=572.0, 95% CI=77.4–4229.3, p<0.001), reduce treats (OR=1166.0, CI=102.3–13291.0, p<0.001), increase physical activity (OR=82.4, CI=20.5–331.1, p<0.001), and to schedule a follow-up appointment for 2–3 weeks (OR=28.6, CI=3.7–223.7, p=0.001). Participants rated the owners of the dog with obesity as less likely than owners of the lean dog to comply with their treatment recommendations (3.6 vs. 4.6, F[1,200]=26.19, p<0.001). No effects of dog or owner body weight were found for desire to continue to treat the dog or prescribed number of treats per day. Similarly, no differences emerged in diagnostic recommendations for a dog presenting with respiratory problems. When the dog was diagnosed with a collapsed trachea, participants were more likely to recommend weight loss treatment for the dog with obesity versus the lean dog (OR=190.8, CI=23.4–1556.2, p<0.001).

Other clinical practices.

Table 2 lists terms endorsed by veterinarians to describe dogs with excess weight to clients and/or colleagues. “Overweight” and “obese” were the most commonly endorsed terms (80–96%), followed by “heavy,” “fat,” and “chunky” (>60% each). Approximately 28% of veterinarians endorsed using terms such as “tick” and “coffee table,” and an additional 10.7% wrote in some variant of the term “ottoman.” Approximately 10% of veterinarians reported that they had counseled owners to seek weight loss treatment from a human health professional (8.3% reported they did this rarely, 2% sometimes or very often). The vast majority of veterinarians (76.1%) recommended that obesity be labeled as a disease in dogs.

Table 2.

Terms endorsed by veterinarians and students to describe excess weight in dogs, N(%)

| Term | Veterinarians | Veterinary Students |

|---|---|---|

| Overweight | 197 (96.1) | 95 (92.2) |

| Obese | 168 (82.0) | 73 (70.9) |

| Heavy | 134 (65.4) | 63 (61.2) |

| Fat | 130 (63.4) | 61 (59.2) |

| Chunky | 125 (61.0) | 79 (76.7) |

| Chubby | 118 (57.6) | 61 (59.2) |

| Morbidly obese | 104 (50.7) | 35 (34.0) |

| Large | 87 (42.4) | 54 (52.4) |

| Plump | 75 (36.6) | 29 (28.2) |

| A tick | 59 (28.8) | 6 (5.8) |

| Coffee table | 58 (28.3) | 11 (10.7) |

| Other (write-in responses) | 46 (22.4) | 14 (13.6) |

| Ottoman/Footstool/End table | 22 (10.7) | 2 (1.9) |

| Fluffy | 24 (11.7) | 16 (15.5) |

| Curvy | 13 (6.3) | 12 (11.7) |

Discussion

Practicing veterinarians endorsed more negative emotional responses toward dogs and owners when the dog had obesity versus was lean. Notably, ratings for some of these emotions were low overall. Veterinarians also reported feeling more compassion toward the dog with obesity and reported respect for dogs and owners regardless of body weight. Still, the observed differences in negative emotional responses by dog body weight provide the first known empirical evidence of potential weight bias among veterinarians.

Owners’ weight interacted with dog weight to shape veterinarians’ beliefs about the causes of the dog’s weight. Lean owners received “credit” for keeping their dogs lean but were seen as less responsible for the dog with obesity’s weight, while owners with obesity were viewed as responsible for their dog’s obesity but not leanness. Similarly, the dog with obesity’s weight was rated as less biologically-based than was the lean dog’s weight when the owners had obesity, but the perceived biological basis of the dog’s weight did not differ when the owners were lean. These observed differences provide further evidence of how dog and owner body weight may bias veterinarians’ assessment of their clients.

As expected, veterinarians were more likely to provide weight-related treatment recommendations for the dog with obesity than for the lean dog. Owners’ weight did not appear to affect these recommendations. Diagnostic recommendations for a dog with respiratory problems also did not differ by dog or owner body weight, although when the dog was described as having a collapsed trachea, weight loss was more likely to be recommended for the dog with obesity versus the lean dog. Weight can affect respiratory health in dogs, suggesting that this may be an appropriate recommendation, as long as other potential causal factors are also considered and not dismissed or ignored (22). In addition, owners of the dog with obesity were rated as less likely to comply with weight-related treatment recommendations than owners of the lean dog. Veterinarians reported use of terms to describe dogs with excess weight such as “fat,” “tick,” “coffee table,” and “ottoman.” The term “fat” is typically perceived as stigmatizing when used to describe humans (23–26), although it is unknown how this and other terms are perceived when used to describe dogs.

Study 2 examined the effects of dog and owner body weight on perceptions among veterinary students. This served as a replication, as well as an investigation of whether weight bias may emerge early in medical training, as has been observed in other preservice health trainees (27,28).

Study 2

Methods

Veterinary students from the same institution as Study 1 were recruited by email over several weeks, with a goal of recruiting 120 participants. Of the 147 students who entered the survey, 103 completed at least the first block of items and were included in the analyses. Table 1 presents participant demographic characteristics. Participants reported their current year in veterinary school. All other procedures were identical to those described in Study 1.

Results

Manipulation check.

As with veterinarians, students rated the dog with obesity as having a significantly higher weight status than the lean dog (6.5 vs. 4.1, p<0.001), and the owners with obesity as having a higher weight status than the lean owners (6.2 vs. 4.2, p<0.001). Interaction effects of dog and owner weight on perceived weight status were not significant.

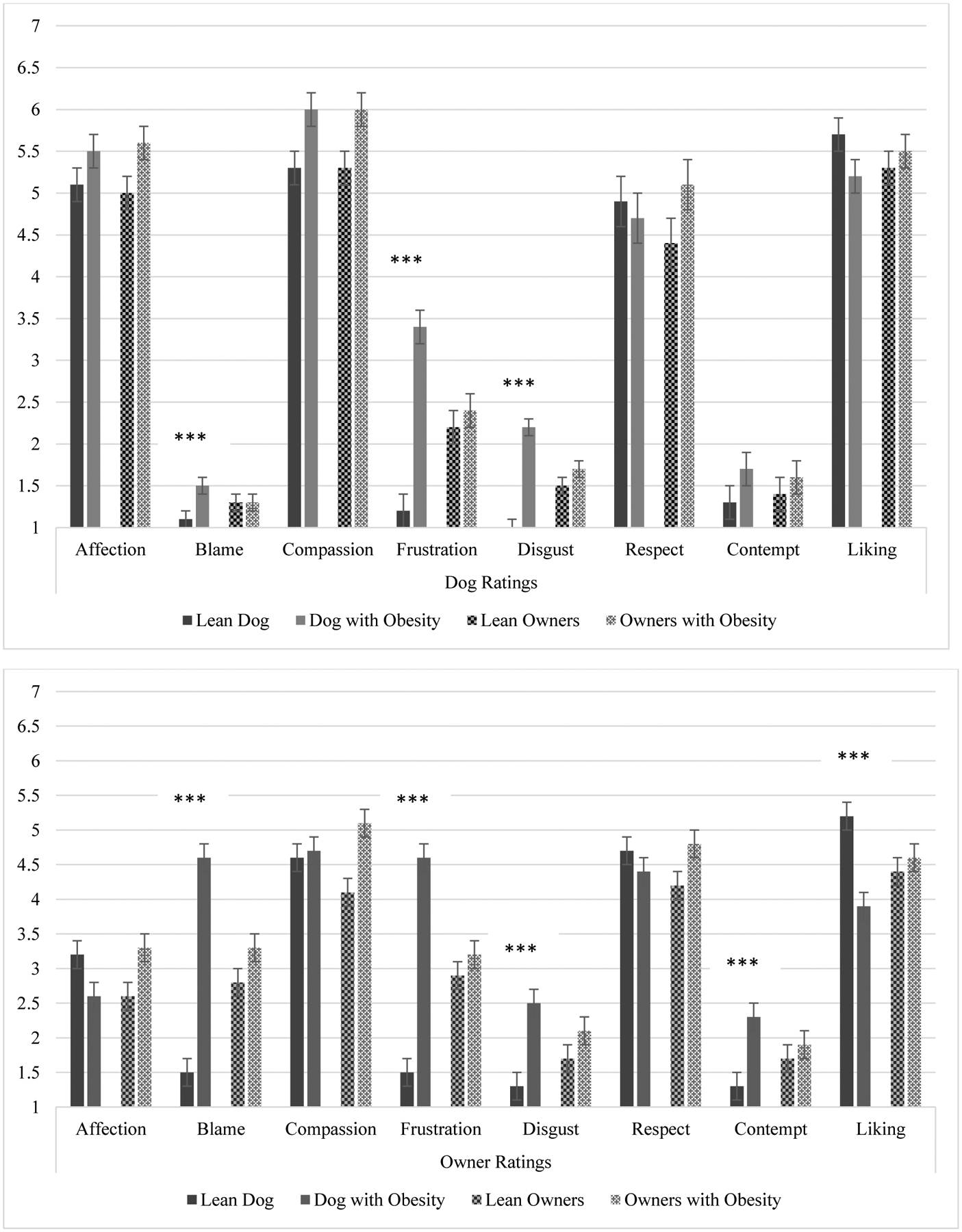

Emotions and liking.

Consistent with Study 1, students reported greater blame, frustration, and disgust toward the dog with obesity compared to the lean dog (Figure 3a, Table S3a). The dog with obesity also elicited significantly higher ratings of blame, frustration, disgust, and contempt toward owners than did the lean dog (Figure 3b, Table S3b). In addition, participants reported liking the owners less if the dog had obesity.

Figure 3.

Veterinary Student Ratings of Emotions and Liking

Figure 3a. Main effects of dog and owner weight on ratings of dogs, ***p<0.001

Figure 3b. Main effects of dog and owner weight on ratings of owners, ***p<0.001

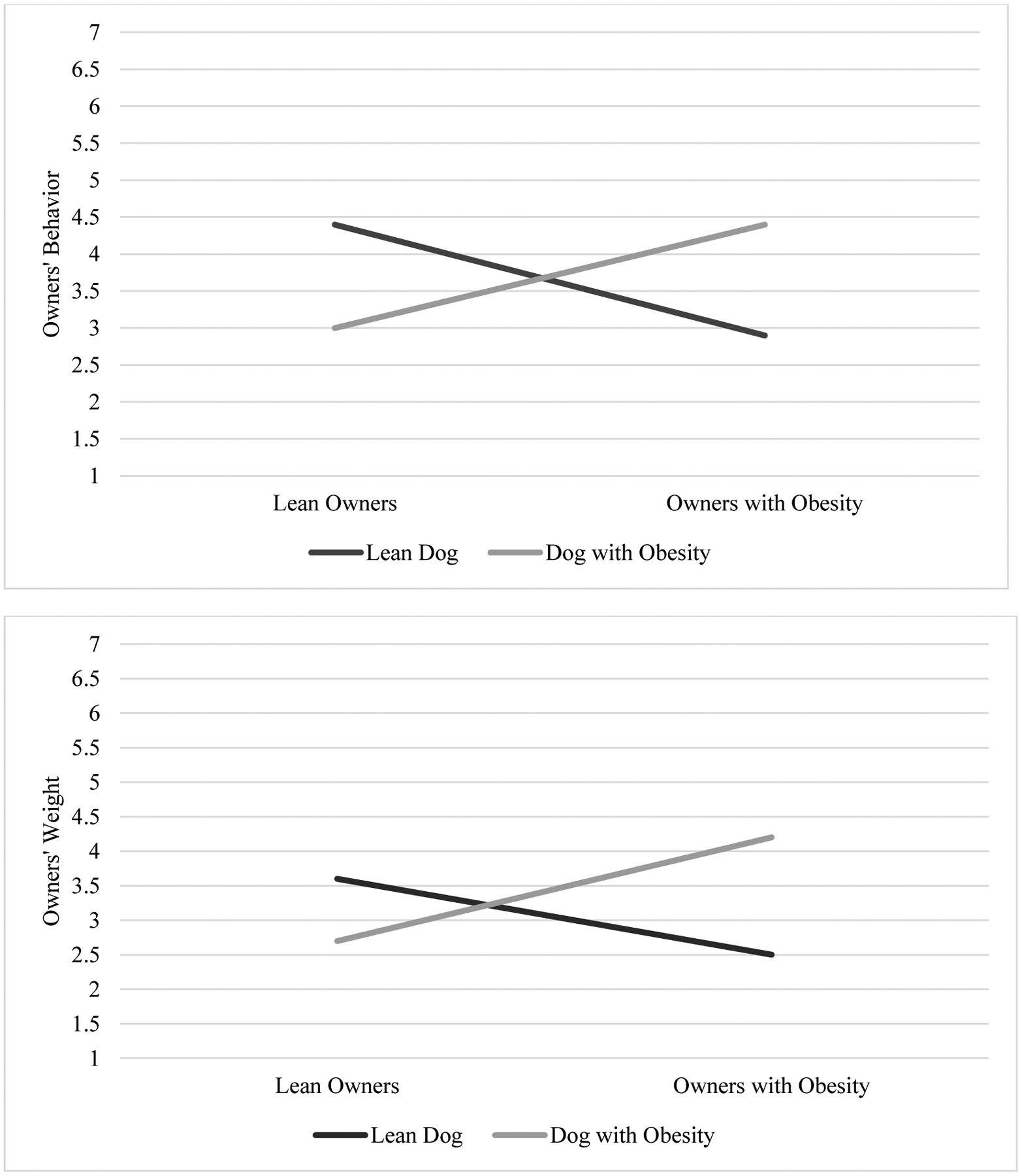

Causes of weight.

Ratings for “owner responsibility” as a cause of dog weight were lower when the dog had obesity versus was lean (p<0.001; Table S4). In addition, dog and owner weight significantly interacted for ratings of owner behavior as a cause of dog weight (Figure 4a). When the owners had obesity, the dog with obesity’s weight was attributed more to owners’ behavior than was the lean dog’s weight (p<0.001). Conversely, when the owners were lean, the lean dog’s weight was rated as more attributable to owners’ behavior than was the dog with obesity’s weight (p=0.002). A significant interaction between dog and owners’ weight was also found for ratings of the effects of owners’ weight on the dog’s weight (Figure 4b). When the owners had obesity, the owners’ weight was rated as having significantly more effect on the dog with obesity’s weight than on the lean dog’s weight, but no such effects emerged when the owners were lean.

Figure 4.

Interaction effects of dog and owner body weight on perceived causes of dog weight among veterinary students

Figure 4a. Interaction effects for owners’ behavior as a cause of dog’s weight

Figure 4b. Interaction effects for owners’ weight as a cause of dog’s weight

Note. Interaction term for Figure 4a: F(1,99)=29.19, p<0.001; Effects of dog weight for lean owners F(1,49)=10.42, p=0.002, and owners with obesity F(1,50)=20.43, p<0.001. Interaction term for Figure 4b: F(1,99)=19.91, p<0.001; Effects of dog weight for lean owners F(1,49)=3.82, p=0.06, and owners with obesity F(1, 50)=22.41, p<0.001.

Treatment recommendations.

Students were more likely to recommend an increase in physical activity, but no other weight-related treatment, for the dog with obesity compared to the lean dog (OR=176.0, CI=17.0–1819.7, p<0.001). Consistent with Study 1, owners of the dog with obesity were rated as less likely to comply with weight-related treatment recommendations than owners of the lean dog (3.8 vs. 5.4, F[1,98]=34.38, p<0.001). When the dog was diagnosed with a collapsed trachea, students were also more likely to recommend weight loss for the dog with obesity versus the lean dog (OR=38.5, CI=7.7–193.0, p<0.001).

Other clinical practices.

“Overweight” was the most common term used to describe a dog with excess weight, followed by “chunky,” then “obese.” Over half of students endorsed using the terms “fat” or “chubby” (Table 2). Only 5–10% reported using the terms “tick” or “coffee table.” Approximately seven percent of students reported counseling owners to speak with a healthcare professional about managing their own weight (2.9% reported they did this rarely, 1.9% sometimes, and 1.9% very often). The majority of students (79.6%) recommended that obesity should be labeled a disease in dogs.

Discussion

Study 2 replicated among veterinary students several of the findings from Study 1. Consistent with Study 1 results, students reported more negative emotions toward the dog and owners when the dog had obesity. Also similar to Study 1, dog and owner body weight interacted in their effects on perceived causes of dog weight. Students attributed the dog’s weight more to owners’ behavior, and to the overall influence of the owners’ weight, when the owners and dog both had obesity. Study 1’s interaction effects for biological attributions of the dog’s weight did not replicate, and students recommended fewer weight loss behaviors for the dog with obesity than did veterinarians. The use of stigmatizing weight-related terms was also slightly lower among students than veterinarians. However, the pessimism about weight-related treatment compliance for the dog with obesity and recommendation of weight loss for a dog with obesity and a collapsed trachea that were observed among veterinarians also appeared among students.

General Discussion

This is the first study to investigate weight bias among practicing veterinarians and students. Across studies, veterinarians and veterinary students reported more negative emotional responses – including disgust, frustration, blame, and contempt – toward dogs and owners when the dog had obesity versus was lean. As noted, the ratings for some of these emotions (e.g., contempt) were low across conditions and did not rise to a level of frank stigmatization. Students reported that they liked the owners less if their dog had obesity, and both veterinarians and students reported pessimism about the owners’ likelihood of complying with weight-related treatment recommendations for the dog with obesity. In human health care, negative automatic emotional responses to patients based on specific characteristics (e.g., race, weight) contribute to implicit bias and differential treatment of patients with stigmatized identities (29). Further research is needed to determine the potential impact of weight bias on veterinarians’ interactions with pet owners and clinical decision making.

When the owners had obesity, students and veterinarians both perceived the owners’ personal relationship to food and health habits as causing the dog with obesity’s weight. They also generally viewed the owners with obesity’s weight as having a stronger effect on the dog with obesity’s weight. Thus, participants made the common assumption that individuals with obesity had poorer eating habits and health behaviors than lean individuals. Seven to ten percent of students and veterinarians reported that they had counseled a pet owner to seek weight management from a human health professional. It is surprising that any participants reported counseling owners about weight, considering that veterinarians are not trained to give health advice to humans. Greater attention is due to whether or not some veterinarians are commenting on owners’ weight or health habits and, as a result, potentially stigmatizing owners with obesity.

Related to this point, more than half of veterinarians and students endorsed use of the term “fat” to describe excess weight in dogs, and up to 28% used the terms “coffee table,” “ottoman,” or “tick.” If these findings were to be replicated in another sample, veterinary organizations may benefit from considering standards for training and practice put forth by human health care organizations for use of non-stigmatizing and patient-centered language in obesity care (7,8). Future studies could investigate the effects on provider-client communication and treatment utilization of respectful and “pet-first” language related to weight among owners of pets with obesity.

Veterinarians viewed the dog with obesity’s weight as less biologically-based when the owners had obesity. In addition, over three quarters of veterinarians and students supported labeling obesity in dogs as a disease. It is possible that framing obesity as a medical condition may reduce stigma, in part by increasing biological attributions for weight and thus reducing blame (30–32). However, the effects on stigma and treatment outcomes of biological attributions for obesity in humans are largely mixed (21,33,34). As causal attributions and disease labeling continue to be examined in humans, veterinarians may also continue to consider how this debate pertains to trainees and practice guidelines in their field.

In a clinical scenario in which a dog presented with a collapsed trachea, veterinarians and students were more likely to recommend weight loss to the dog with obesity than the lean dog. Weight is one of many factors than can cause respiratory problems in dogs (22), and practitioners who focus on weight loss in their recommendations may miss other potential health issues that require treatment (4). Future studies could potentially test for veterinarians’ ability to accurately diagnose obesity in dogs and identify its known comorbidities. Owner body weight did not appear to affect treatment recommendations in this study. Studies that assess treatment recommendations in simulated clinical scenarios with standardized patients could further elucidate the potential effects of body weight on treatment recommendation for conditions that may not be entirely related to obesity.

Strengths of the current studies included the novel investigation of weight bias in a previously neglected population of health professionals, replication in two different veterinary samples, and use of a randomized, experimental design to assess causal effects. The studies were limited by sampling from a single institution, use of hypothetical dog/owner drawings and vignettes, reliance on self-report measures, and a sole focus on perceptions of dogs (versus other types of pets, such as cats). Due to the high number of comparisons (resulting in a conservative statistical adjustment) and a relatively small sample size (particularly for students), the analyses may have been limited in their power to detect some statistically-significant findings. Further replication in a larger, multi-site study is needed to verify results from this preliminary investigation of weight bias among veterinarians.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

RLP is supported by a K23 Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the NIH (K23HL140176).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no competing interests to disclose. RLP is supported by a K23 Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the NIH (K23HL140176).

To reduce the number of comparisons, sensitivity analyses were also conducted by dividing emotion ratings into two categories of positive and negative emotions. Results were consistent with those presented here and were not included due to less specificity in emotion ratings.

Supplementary information is available at the International Journal of Obesity’s website.

References

- 1.M, Panigrahi E, Egner R, Webb V, et al. Patients’ preferred terms for describing their excess weight: 1. Kushner RF, Batsis JA, Butsch WS, Davis N, Golden A, Halperin F, et al. Weight history in clinical practice: The state of the science and future directions. Obesity. 2020;28(1):9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberga AS, Pickering BJ, Hayden KA, Ball GDC, Edwards A, Jelinski S, et al. Weight bias reduction in health professionals: A systematic review. Clin Obes. 2016;6:175–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebl MR, Xu J. Weighing the care: Physicians’ reactions to the size of a patient. Int J Obes. 2001;25:1246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phelan SM, Burgess DJ, Yeazel MW, Hellerstedt WL, Griffin JM, Ryn M. Impact of weight bias and stigma on quality of care and outcomes for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2015;16:319–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Healy M, Gorman A. AMA declares obesity a disease. Los Angeles Times. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pont SJ, Puhl R, Cook SR, Slusser W, The Obesity Society. Stigma experienced by children and adolescents with obesity. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyle TK, Puhl RM. Putting people first in obesity. Obesity. 2014;22(5):1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanford FC, Kyle TK. Respectful language and care in childhood obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1001–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manson JE, Skerrett PJ, Greenland P, Vanltallie TB. The escalating pandemics of obesity and sedentary lifestyle: A call to action. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(3):249–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farcas AK, Michel KE, editors. Small Animal Obesity Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartges J, Kushner RF, Michel KE, Sallis R, Day MJ. One Health solution to obesity in people and their pets. J Comp Pathol. 2017;156:326–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.German AJ, Holden SL, Brennan L, Burke C. Dangerous trends in pet obesity. Vet Rec. 2018;182:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamlington B, Ivey LE, Brenna E, Biesecker LG, Biesecker BB, Sapp JC. Characterization of courtesy stigma perceived by parents of overweight children with Bardet-Biedl Syndrome. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0140705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holub SC, Tan CC, Patel SL. Factors associated with mothers’ obesity stigma and young children’s weight stereotypes. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2011;32:118–26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Routledge; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 16.VanVoorhis CRW, Morgan BL. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol. 2007;3(2):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabin JA, Marini M, Nosek BA. Implicit and explicit anti-fat bias among a large sample of medical doctors by BMI, race/ethnicity and gender. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e48448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCleary-Gaddy AT, Miller CT, Grover KW, Hodge JJ, Major B. Weight stigma and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis reactivity in individuals who are overweight. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53(4):392–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pearl RL, Argueso D, Wadden TA. Effects of medical trainees’ weight-loss history on perceptions of patients with obesity. Med Educ. 2017;51(8):802–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruttan RL, McDonnell M, Nordgren LF. Having “been there” doesn’t mean I care: When prior experience reduces compassion for emotional distress. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2015;108(4):610–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearl RL, Lebowitz MS. Beyond personal responsibility: Effects of causal attributions for obesity on weight-related beliefs, stigma, and policy support. Psychol Health. 2014;29(10):1176–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chandler ML. Impact of obesity on cardiopulmonary disease. Farcas AK and Michel KE, editors. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puhl RM, Peterson JL, Luedicke J. Motivating or stigmatizing? Public perceptions of weight-related language used by health providers. Int J Obes. 2013;37:612–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Puhl RM, Peterson JL, Luedicke J. Parental perceptions of weight terminology that providers use with youth. Pediatrics. 2011;128:786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wadden TA, Didie E. What’s in a name? Patients’ preferred terms for describing obesity. Obes Res. 2003;11(9):1140–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volger S, Vetter ML, Dougherty Discussing obesity in clinical practice. Obesity. 2012;20:147–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phelan SM, Dovidio JF, Puhl RM, Burgess DJ, Nelson DB, Yeazel MW, et al. Implicit and explicit weight bias in a national sample of 4732 medical students: The medical student CHANGES study. Obesity. 2014;22(4):1201–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Brien KS, Puhl RM, Latner JD, Mir AS, Hunter JA. Reducing anti-fat prejudice in preservice health students: A randomized trial. Obesity. 2010;18:2138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacInnis CC, Alberga AS, Nutter S, Ellard JH, Russell-Mayhew S. Regarding obesity as a disease is associated with lower weight bias among physicians: A cross-sectional survey study Stigma Health. 2019: Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nutter S, Alberga AS, MacInnis C, Ellard JH, Russell-Mayhew S. Framing obesity as a disease: Indirect effects of affect and controllability beliefs on weight bias. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1804–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ata RN, Thompson KJ, Boepple L, Marek RJ, Heinberg LJ. Obesity as a disease: Effects on weight-biased attitudes and beliefs. Stigma Health. 2018;3(4):406–16. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McVay MA, Steinberg DM, Askew S, Kaphingst KA, Bennett GG. Genetic causal attributions for weight status and weight loss during a behavioral weight gain prevention intervention. Genet Med. 2016;18(5):476–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hilbert A Weight stigma reduction and genetic determinism. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(19):e0162993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.