Abstract

Medication-related problems are a leading cause of morbidity and mortality. Patients requiring dialysis are at a heightened risk of adverse drug reactions because of the prevalence of polypharmacy, multiple chronic conditions, and altered (but not well understood) medication pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics inherent to renal failure. To minimize preventable medication-related problems, healthcare providers need to prioritize medication safety for this population. The cornerstone of medication safety is medication reconciliation. Here, we present a case highlighting adverse outcomes when medication reconciliation is insufficient at care transitions. We review available literature on the prevalence of medication discrepancies worldwide. We also explain effective medication reconciliation and the practical considerations for implementation of effective medication reconciliation in dialysis units. In light of the addition of medication reconciliation requirements to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Quality Incentive Program, this review also provides guidance to dialysis unit leadership for improving current medication reconciliation practices. Prioritization of medication reconciliation has the potential to positively impact rates of medication-related problems, as well as, medication adherence, healthcare costs, and quality of life.

Keywords: Patient safety, Medication discrepancy, Adverse drug events, Quality improvement, Renal failure

Medication reconciliation case

An 89-year-old man receiving peritoneal dialysis (PD) presented to the emergency room (ER) with one day history of fever, malaise and unilateral rash. He was diagnosed with herpes zoster and prescribed acyclovir 800 mg orally five times daily for seven days and gabapentin 300 mg orally three times daily and was discharged to home. Three days later, he sustained a fall with injury (hip fracture requiring hip replacement) and returned to the hospital via emergency medical services (EMS). The EMS team brought the patient’s medication bottles to the hospital, and they were used to reconcile his medications. Nephrology was consulted for dialysis during his inpatient stay, and it was noted that acyclovir and gabapentin doses were inappropriately high. Doses were then appropriately reduced in the hospital, based upon the patient’s PD status.

The patient was discharged to a rehabilitation facility to undergo physical and occupational therapy. During this time, the patient was prescribed oxycodone/acetaminophen 10 mg-325 mg tablet orally every six hours as needed for pain management and a bowel regimen for constipation. As part of his bowel regimen he was administered sodium phosphate enema. As for many dialysis patients, medication reconciliation at the dialysis unit was deferred until after discharge from the inpatient rehabilitation facility; therefore, the patient order for sodium phosphate enema was not discovered. On monthly labs, the patient’s serum phosphorus concentration was elevated to 10 mg/dL and the dialysis team increased the patient’s phosphate binder dose.

After 34 days, the patient was discharged home from the rehabilitation facility. Upon discharge, the patient continued to take his opioid therapy but his bowel regimen medications were not continued. Three days later while at home, the patient experienced severe abdominal pain. He went to the emergency department (ED) and an abdomen scan showed significant constipation, likely due to the regular use of opioids. His laboratory results also revealed low serum phosphorus of 2.1 mg/dL. The patient was treated with lactulose for his constipation and his phosphorus binders were held due to low phosphorus levels and potential to cause constipation.

Introduction:

Knowing what medications a patient is taking is foundational for medication safety programs. The process used to obtain and maintain patient medication use information is called medication reconciliation.

The aforementioned case highlights the importance of medication reconciliation at each transition of care. Performing medication reconciliation after initial ED discharge could have identified the inappropriate medication dosing (e.g., acyclovir and gabapentin) and avoided injury (e.g., hip fracture from fall). If medication reconciliation was completed as part of routine care at the dialysis unit, high-risk medications could have been identified early (e.g., sodium phosphate enema) to prevent the subsequent prescribing cascade (e.g., increasing phosphate binder dose to treat hyperphosphatemia caused by enema). Finally, medication reconciliation upon discharge to home from the rehabilitation facility could have identified therapy omission (e.g., no bowel regimen for patient on opioid therapy) and medication overdose (e.g., high phosphate binder dose in absence of phosphate enema) and possibly prevented subsequent ED visit.

We review the evidence describing the prevalence of medication discrepancies and their clinical impact in patients requiring dialysis, describe current and near future Medicare requirements for medication reconciliation at dialysis units, and provide best practice processes for medication reconciliation.

The Significance of Medication discrepancies

Patients on hemodialysis (HD) are at particularly high risk of discrepancies between medication orders and actual consumption due to highly complex medication regimens.1–2 On average, HD patients consume five to 14 medications and 17 to 25 doses per day.3–4 It has been reported that HD patients have two to nine physicians and five to 11 comorbid conditions.5 Moreover, patients with end stage kidney disease (ESKD) are admitted to the hospital nearly twice a year.6 Complex medical problems, frequent hospitalizations and having multiple physicians results in frequent medication-related problems in these patients.7 These medication-related problems contribute significantly to the resources spent on ESKD care.1–2

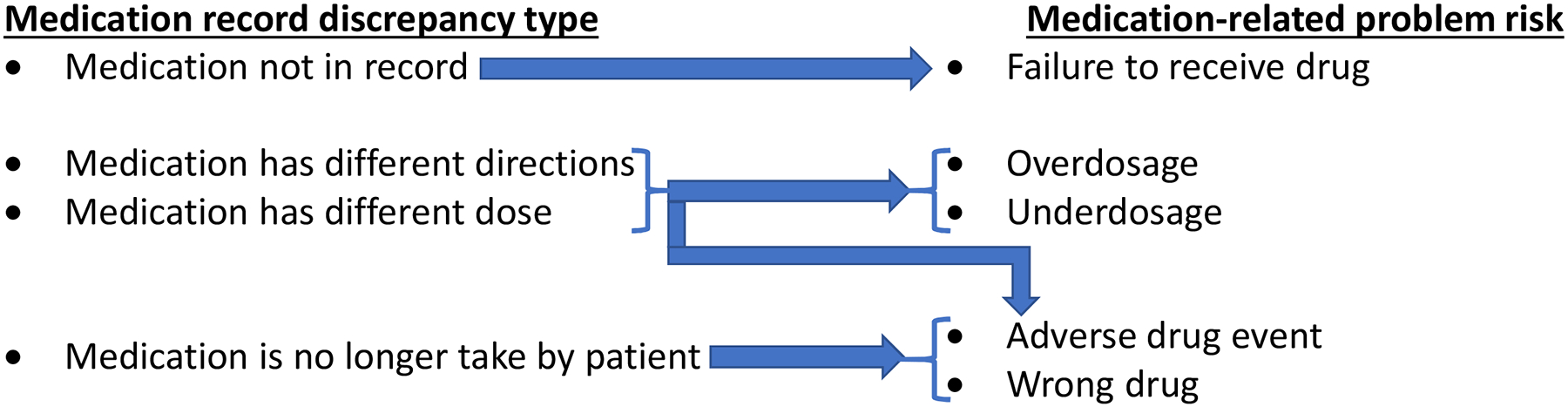

Medication discrepancies can be classified into four groups: no-longer taking (i.e., patient is no longer taking a medication that clinicians thought they were), not in record (i.e., patient is taking a medication that the clinician was not aware of), dosing issue (i.e., patient is taking a different dose than the clinician thought they were taking) and direction issue (e.g., patient is taking correct dose but at different frequency than that the clinician thought they were).8 (Figure 1.) Additionally, each medication discrepancy type places a patient at risk for a medication-related problem.8 Since 2003, studies worldwide have demonstrated medication discrepancy prevalence and type observed in dialysis patients (Table 1).8–14 Overall, they illustrate that on average two to three (range 1.3–3.9) medication discrepancies can be identified each time a dialysis patient has their medications reconciled. The most common medication discrepancy types are “medication no longer taken” and “medication not in record” which can place patients at risk for medication adverse drug events, over- or under- dosage, failure to receive necessary medication and wrong medication.

Figure 1.

Medication related problems associated with medication record discrepancies.

Based on information in Manley, et al.8

Table 1.

Medication record discrepancies (MRD) reports in dialysis patients.

| Study | Country | Medication Reconciliation Approach | # Patients | Frequency of Medication Reconciliation | # MRD Identified | Mean # of MRD per patient | Most common type of MRD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manley, et al. 20038 | USA |

|

215 | Monthly event* | 113 | 1.7 | Patient no longer taking medication |

| Lindberg, et al. 20079 | Sweden |

|

204 | Single event | 590 | 3.6 | Patient no longer taking medication |

| Ledger, et al. 200810 | Canada |

|

19 | Single event | 62 | 3.3 | Medication not in record |

| Leung, et al. 200911 | Canada |

|

93 | Single event | 358 | 3.9 | Patient no longer taking medication |

| Chan, et al. 201512 | Canada |

|

151 | Single event | 512 | 3.4 | Medication dose or directions discrepancy |

| Patricia, et al. 201613 | USA |

|

124 | Single event | 376 | 3.1 | Medication not in record |

| Wilson, et al. 201714 | Canada |

|

147 | Multiple events* | 193 | 1.3 | Medication dose or directions discrepancy |

In these studies, there was more than one reconciliation event per patient for some patients.

Dialysis units often provide patient medication lists to the ED or hospitals whenever the patient is admitted; therefore, a dialysis unit’s medication list serves as a very important clinical document. Assuming that two to three medication discrepancies are found whenever a dialysis patient has medication reconciliation, extrapolating this to the entire United States (US) population of HD (n=468,086) and PD (n=52,718) patients suggests that approximately 1 – 1.6 million medication discrepancies could be identified.6 It is estimated that 4–6% of medication discrepancies are clinically relevant and place patient at risk for harm.12,14 Therefore, the US dialysis population has an estimated 41,664 – 93,744 clinically significant medication discrepancies that could cause patient harm.

Two studies highlight the risk related to medication discrepancies for dialysis patients. One study of adults hospitalized via the ED found that 97 of 832 patients (11.7%) had at least one medication discrepancy, the most common discrepancies were incorrect medication dose (44.9%) and not in record (36.4%).15 Characteristics independently associated with medication discrepancies were age (OR=1.02 [95%CI 1.01–1.03]) and medication count (OR=1.10 [95%CI 1.06–1.15]), highly relevant to increasing age and polypharmacy common in the US dialysis population. Another report of 47 dialysis patients admitted to the hospital over a 12-week period identified that 92% of patients with ESKD had at least one medication-related problem at admission (total 199 distinct issues).16 The authors determined that 130 (65%) of those issues were related to “gaps in medication information transfer.” (i.e., medication discrepancy) most frequently between the inpatient hospital and the ambulatory clinic pharmacists (21.5% of time) and between the admitting physician and the patient (17.7% of time).16 Overall, these findings suggest that dialysis patients are at high risk of medication discrepancies. To minimize these discrepancies, there is need for high quality medication reconciliation in dialysis units and subsequent communication of the updated patient medication lists to other care settings.

Medication reconciliation in dialysis units

Given the evidence for medication discrepancies worldwide, standardized programs and policies to promote medication reconciliation are warranted. An example of a standardized program is the Manitoba Renal Program’s integration of renal pharmacists to conduct medication reconciliation at intervals and care transitions.17 Medication reconciliation is also a requirement for dialysis units in the US. The Conditions for Coverage for ESRD Facilities states that the patient plan of care includes “Medication history” and that it should be developed within 30 days of patient admittance to a dialysis unit, annually for stable patients and monthly for unstable patients.18 Additionally, the dialysis unit survey tag V506 “Immunization history, and medication history“ states that “Medication history” should include a review of the patient’s allergies and all medications including over-the-counter medications and supplements that the patient is taking. The assessment should demonstrate that all current medications were reviewed for possible adverse effects/interactions and continued need.”19

More recently, a new proposal to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recommended adopting medication reconciliation as a quality metric for End Stage Renal Disease Quality Incentive Programs (QIP).20 The Kidney Care Quality Alliance defines medication reconciliation as “the process of creating the most accurate list of all home medications that the patient is taking, including name, indication, dosage, frequency, and route, by comparing the most recent medication list in the dialysis medical record to one or more external list(s) of medications obtained from a patient or caregiver (including patient-/caregiver- provided ‘brown bag’ information), pharmacotherapy information network (e.g., Surescripts), hospital, or other healthcare provider.”21 The intermediate outcome desired is improved and expedited identification of real and potential mediation-related problems. The anticipated health outcomes associated with medication reconciliation are reduction of medication-related problems associated with hospitalizations, readmission, mortality and health care costs.

Beginning 2022, medication reconciliation will be included in the Medicare QIP Safety Domain.22 US dialysis units will be required to attest to providing monthly medication reconciliation on all dialysis patients having more than seven treatments provided in the unit that reporting month. Eligible individuals to perform medication reconciliation include: physician, registered nurse, advanced registered nurse practitioner (ARNP), physician assistant, pharmacist, or pharmacy technician. Evidence from other clinical settings suggests pharmacists provide more comprehensive medication reconciliation than physicians.23–26 The measure requires dialysis organizations to provide medication reconciliation on a monthly basis using qualified personnel.

Under the medication reconciliation reporting measure, dialysis units will have to attest that four items were addressed and documented during the calculation month: 1.) the patient’s most recent medication list in the dialysis medical record was reconciled to one or more external list(s) of medications obtained from the patient/caregiver (including patient/caregiver provided “brown-bag” information, pharmacotherapy information network (e.g., Surescripts®), hospital, or other healthcare provider); 2.) all known medications (prescriptions, over the counter medications, herbals, vitamin/mineral/dietary [nutritional] supplements, and medical marijuana) were reconciled; 3.) all of the following items were addressed for each identified medication: medication name, indication, dosage, frequency, route of administration, start and end date (if applicable), discontinuation date (if applicable), reason medication was stopped or discontinued (if applicable), identification of individual who authorized stoppage or discontinuation of medication; and 4.) all allergies, intolerances, and adverse drug events. Of the medication-related data elements, “Unknown” is an acceptable response for all except “medication name”.22

Under this reporting measure, CMS will determine the percentage of patient-months for which medication reconciliation was performed and documented by eligible professionals. During measure testing between April 1 and Sept 30, 2015 in 325,000 patients at 5,292 dialysis units, the mean percentage was 52.6 ± 32.8% (median 48.2%; range 0–100%; IQR 27.6% to 87.8%).21 Although a specific goal is not yet known, a high percentage is desired. The data sources used to calculate percentage of patient-months with medication reconciliation will be: Consolidated Renal Operations in a Web-Enabled Network (CROWNWeb) which is the ESRD National Patient Registry and Quality Measure Reporting System for CMS, facility medical records, and administrative data. In January 2020, CROWNWeb medication reconciliation data reporting began for all HD and PD patients. Dialysis units are not required to report the data; however, the system provides users with the ability to review the medication reconciliation fields in preparation for data reporting.

To prepare for this medication reconciliation QIP measure, dialysis units need to consider both external and internal challenges. One significant external challenge is electronic medical record silos among dialysis units, hospitals, and other health care clinics. Different settings have varying levels of information sharing. Some dialysis providers such as within the US-based Veteran’s Affairs (VA) system, may have a greater extent of information exchange between care transitions than for private dialysis providers. In the VA system, health records and prescribing systems are typically shared between clinics and hospitals. However, not all veterans receive all of their care solely from providers within the VA system. Less than 4% of veterans receive dialysis treatments at a VA.27 Other issues of medical record silos that can occur in any setting include outdated or unreliable electronic records based on a number of factors, such as paying cash for medications, non-adherence, or changes to regimen that are not yet documented. This separation of records limits information-sharing among healthcare providers and yields separate and distinct medication lists.28 One potential solution to overcome this challenge may be integrating a process for systematic transfer of discharge medication lists from hospitals to dialysis units.

Significant internal challenges to medication reconciliation may include resistance by leadership and clinicians to adequately resource medication reconciliation, due to competing organizational priorities, limited resources, or confusion over whose responsible for performing medication reconciliation.29,30 It will be important to get leadership support to implement processes that facilitate medication reconciliation including training staff and integrating medication reconciliation into the workflow. Leadership and clinicians should also recognize potential benefits of medication reconciliation, such as preventing hospitalizations and missed treatments, and cost avoidance associated with missed treatments. In the coming years, proactively identifying barriers and establishing medication reconciliation programs will be essential to the success of medication safety efforts. Regardless of the various challenges dialysis units will face to implement medication reconciliation, it will be important to overcome barriers to adhere to the metric, and improve clinical care and outcomes for dialysis patients.

There are many innovations which may improve the efficiency and accuracy of medication reconciliation. Studies have found that pharmacy technicians may be a cost effective and efficient staffing solution.11,31 Tools such as artificial intelligence decision (AI) support software and hardware (e.g., tablets) in primary care clinics may assist with medication reconciliation, increase patient engagement, and assist in creating the best possible medication history engage patients.32–33

Dialysis organizations should create appropriate policy and procedures, training materials for professionals conducting medication reconciliation, and track medication reconciliation metrics in clinic Quality Assurance and Performance Improvement (QAPI) program. There are several resources available to units that need to create or enhance their current medication reconciliation practices including: the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) medication reconciliation toolkit: the Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) guide book for creating medication management systems with tools and videos on obtaining the Best Medication History/Best Medication Discharge plan, the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) guide book for medication reconciliation quality improvement resources and ESRD Forum and Network resources for medication management and medication reconciliation.34–36

Best Practices for Medication Reconciliation

The goals of medication reconciliation are to identify medication list discrepancies, and create the most accurate medication list for patient and healthcare provider use. Having an accurate medication list provides valuable information to clinicians as they make care management decisions (i.e., medication review process). Most medication reconciliation guidance addresses care transitions and provision of information to primary care providers, but not details on the optimal setting and timing for performing medication reconciliation for dialysis patients.34–36 While no standardized, uniform process for medication reconciliation exists for dialysis units, several studies around the development and implementation of medication reconciliation programs describe best practices and their potential impact (Table 2). A notable example of program development and implementation is the AHRQ funded MARQUIS study.35 The study developed a medication reconciliation toolkit to provide resources for organizations seeking to reduce medication errors occurring at care transitions. The toolkit includes an implementation manual, training videos for taking medication histories and providing medication counseling, and a return-on-investment calculator for medication reconciliation quality improvement investments.

Table 2.

Dialysis facility medication reconciliation best practices.

| Best Practice | Impact |

|---|---|

| Make available a medication reconciliation Policy and Procedure that clearly defines what medication reconciliation is, and what the expectations are for performance |

|

| Clearly define roles/responsibility of staff; use a team based approach |

|

| Provide adequate staff training, evaluate competency and promote accountability |

|

| Maintain one centrally located medication list that is able to be updated by the patient and healthcare providers |

|

| Perform medication reconciliation monthly and following care transitions, and after events like falls, dental procedures, or other pain related care appointments. |

|

| Use automation and prompts to integrate medication reconciliation into existing workflow of the dialysis unit |

|

| Provide a medication list to the patient and other healthcare providers as appropriate/allowed |

|

| Develop a quality improvement program |

|

Alternatively, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s three-step process could be applied to dialysis units, with some modifications.37 The three steps are: 1) verification 2) clarification and 3) documentation of communications. Because outpatient dialysis units often operate as silos, we recommend separating communication and adding it as a fourth step. (Table 3). This underscores how crucial effective, coordinated interprofessional communication is for maintenance of the medication list over time. The dialysis unit could be an ideal site for a centralized medication list, due the frequent nature of patient contact, as well as the ability to undertake close monitoring and follow up.28

Table 3.

Medication reconciliation steps and associated task(s) and goal(s).

| Medication Reconciliation Step | Task(s) | End Goal(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Verification (gathering information) |

|

|

| 2. Clarification |

|

|

| 3. Documentation |

|

|

| 4. Communication |

|

|

In order to perform medication reconciliation, at least two sources of medication use information are needed, such as, but not limited to, the patient, healthcare provider, acute or chronic care institution documents, electronic medical record and brown bag. Clinicians often recommend that patients “brown bag” their medications for office visits. The goals of brown bag medication review are to allow clinicians to actually view what the patient is using and provide an opportunity to actively engage patients in discussing and reconciling medications. The brown bag process requires that patients bring in all their medications to the clinic for review.37 Unfortunately, the brown bag process is difficult to implement as patients often times do not remember to bring in their medications for review.

Not only is brown bag medication reconciliation process difficult to actually complete, even in patients that do participate in the brown bag process their participation alone may not be sufficient to create an accurate medication list when compared to those that provide a medication list alone.38,39 Despite bringing in medications for a brown bag event, the resultant medication list may not be accurate as patients may not bring in all of their medications for reconciliation. This may be for a variety of reasons, such as multiple medication storage sites around home (e.g., bedside, bathroom, dining table, refrigerator), or not appreciating that over-the-counter medications (e.g. pain relievers, cough and cold products, vitamins and herbal products) need to be included. Although medication list accuracy may not differ between those that brown bag versus those that do not, patients who brown bag their medications prompt healthcare providers to conduct a more thorough medication history. Innovative measures that increase patient engagement and facilitate brown bag method of medication reconciliation are timely and necessary. For example, patient participation in brown bag medication reconciliation improves by 50% when telephone and secure messaging via patient portal reminders are utilized.40

After the medication list is updated and discrepancies identified, the list should be presented to the patient’s nephrologist for their review and resolution of any medication discrepancy as clinically appropriate. Next, the updated and finalized medication list should be documented in the clinic medical record along with date and clinician name that performed medication reconciliation. If any medication discrepancies remain unresolved, a plan of action should be created and progress tracked during patient care conferences. The final step is to share the updated medication list with the patient and their healthcare providers.

Providing the updated medication and allergy list to the patient serves multiple purposes. First, it alerts them to any changes or clarifications that may have occurred as a result of clinicians resolving discrepancies. Patients can use the new list as a reference for how to take their medications. Additionally, it gives them a resource that they can share with any other healthcare providers who may not have received the most up-to-date list. Going over the list with the patient is an opportunity to educate the patient about their medication regimen and ensure they understand it. We also encourage getting permission from the patient to allow the dialysis unit to directly share the patient’s updated medication and allergy list with their healthcare provider(s) and pharmacy(ies). Two studies illustrate benefits of sharing an updated medication lists to a dialysis patient’s healthcare providers. Wilson, et al. found that nearly 90% of family physicians and community pharmacists who received updated medication reconciliation forms for dialysis patients were satisfied and felt it improved quality of care.14 Riley and Wazny also surveyed community pharmacists and family physicians, and had similar findings. Over 80% of survey respondents indicated they would use the provided (faxed) medication profile to update their records and felt it was a worthwhile project to continue, and over 90% felt that the document improved communication with the dialysis unit.41 Providers also reported that having an accurate and contemporary medication list saved them time required to care for patients who are on dialysis.14,41

Outcomes associated with Medication Reconciliation

A structured and frequent medication reconciliation program should result in more accurate records of which medications the patient is actually taking, which medications the patient should be taking and which medications the patient has experienced adverse reactions to. Intuitively, it seems plausible that this would also positively impact in-center patient care. Theoretically, medication related problems can make dialysis treatments go awry leading to missed or shortened treatments, which in turn could disrupt the unit’s schedule for the day, and result in lost revenue from missed treatments. Given the relatively large proportion of time (nine to 12+ hours per week) that patients spend in the dialysis unit, it’s conceivable that non-dialysis-related medication adverse events may occur while the patient is present at a dialysis unit (e.g., patient may experience altered mental status changes or fall while at dialysis unit due to newly prescribed central nervous system depressant [e.g., opiate, antihistamine, benzodiazepine, gabapentin], patient may experience intradialytic hypotensive episode after a new antihypertensive has been added to their regimen, patient may experience prolonged bleeding after initiation of antithrombotic therapy, hypoglycemia from a sulfonylurea, arrhythmias due to medication interactions). Beyond patient care, potential downstream effects of medication reconciliation include improvements in medication adherence, medication appropriateness, costs, and quality of life.

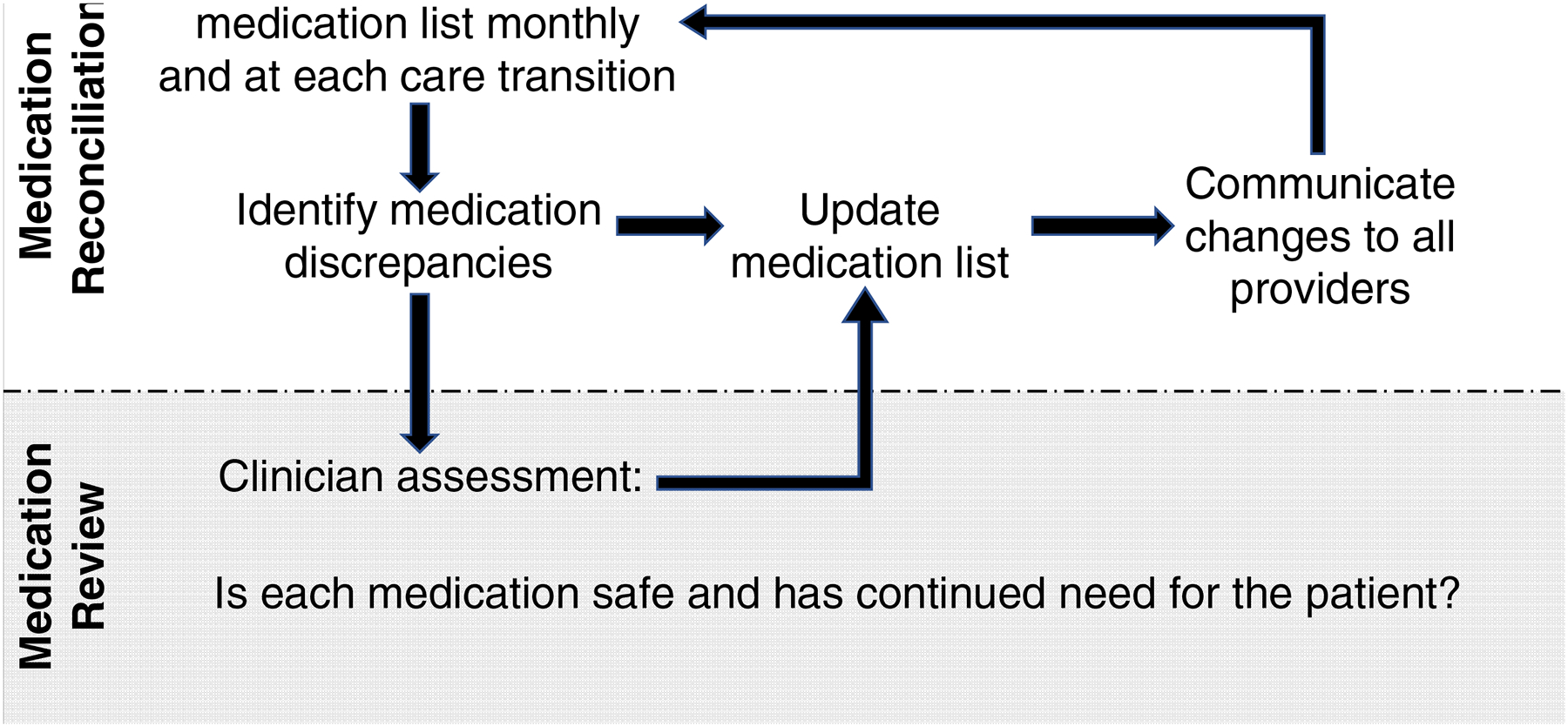

Clearly, medication reconciliation in dialysis patients can identify clinically significant discrepancies8–14 and can be considered integral for patient safety programs at dialysis units. However, maximal benefit from medication reconciliation will be realized only if subsequent medication review occurs (Figure 2). Medication review is the structured process whereby a clinician makes clinical decisions based upon the medication use information.2 Dialysis patients that participate in a structured program of combined medication reconciliation and medication review processes involving pharmacists experience lower hospitalization and readmission rates.42,43 One 2-year trial randomized 104 hemodialysis patients to receive either bimonthly usual care consisting of nurse medication reconciliation or a medication review that also included clinical pharmacist identification and resolution of various medication related issues. Patients receiving additional medication review services had fewer hospitalizations (1.8±2.4 versus 3.1±3, P=0.02) and trended towards reduced lengths of stay (10±15 versus 16±16 days, P=0.06).42

Figure 2.

Difference between Medication Reconciliation and Medication Review

In a retrospective cohort study of maintenance dialysis patients discharged home from acute-care hospitals, patients that received medication therapy management services consisting of nurse medication reconciliation, pharmacist medication review, and nephrologist engagement had lower time-varying 30-day readmission risk (HR 0.26; 95% CI 0.15–0.45) versus those that did not receive medication therapy management).43 In a propensity score matched sensitivity analysis, medication therapy management services continued to be associated with lower 30-day readmission risk (HR 0.20; 95% CI 0.06–0.69).43 Dialysis unit leadership should recognize the potential value that high quality medication reconciliation, as a foundation for medication review, could bring to other QIP measures, such as the Standardized Readmission Ratio and Standardized Hospitalization Ratio.

Conclusion

Due to unusually complex medication regimens, altered pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, frequent care transitions, utilization of multiple healthcare providers, and high comorbidity rate, dialysis patients are at particularly high risk for adverse medication events. Resolution of potentially harmful medication-related problems is predicated on the identification of medication list discrepancies through the medication reconciliation process. To reduce the incidence of medication-related adverse effects and effectively resolve medication-related problems, it is critical for dialysis providers to advance the priority of establishing and maintaining a comprehensive medication reconciliation process, which can serve as the foundation for a robust medication safety program.

Moreover, US clinicians should be aware that in 2022 the reporting requirements for the CMS ESRD QIP will include medication reconciliation data. The QIP Safety Domain specifies that medication reconciliation performed by qualified personnel must be completed at least monthly for all patients who received seven or more treatments in that clinic’s reporting month. Multiple resources and step-by-step guides are available to facilitate healthcare providers’ efforts to meet the QIP for medication reconciliation requirements.

In preparation for the QIP, clinicians should engage in a systematic approach for developing medication reconciliation policies and procedures, staff training, and integration of medication reconciliation into the workflow. Dialysis providers should proactively seek to identify and address any internal (e.g., leadership support) and external (e.g., multiple medical records among providers) barriers to medication reconciliation in order to prepare for and comply with the upcoming QIP. In addition to meeting QIP requirements and avoiding associated negative financial consequences, medication reconciliation will lay a strong foundation for the medication review process and ultimately improve patient care.

Support:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging K76AG059930 (RH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Research was also supported by the American Society of Nephrology Foundation for Kidney Research (RH) and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Grant 2015207 (RH). These sponsors had no role in defining the content of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: the authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

References:

- 1.Kidney Care Quality Alliance (KCQA): Medication Reconciliation for Patients Receiving Care at Dialysis Facilities. 2017. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/NQF-2988-Patients-Receiving-Care-at-Dialysis-Facilities.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020

- 2.Pai AB, Cardone KE, Manley HJ, et al. Medication reconciliation and therapy management in dialysis-dependent patients: need for a systematic approach. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(11):1988–1999. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01420213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardone KE, Manley HJ, Grabe DW, Meola S, Hoy CD, Bailie GR. Quantifying home medication regimen changes and quality of life in patients receiving nocturnal home hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2011;15(2):234–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2011.00539.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiu YW, Teitelbaum I, Misra M, de Leon EM, Adzize T, Mehrotra R. Pill burden, adherence, hyperphosphatemia, and quality of life in maintenance dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(6):1089–1096. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00290109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rifkin DE, Laws MB, Rao M, Balakrishnan VS, Sarnak MJ, Wilson IB. Medication adherence behavior and priorities among older adults with CKD: a semistructured interview study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(3):439–446. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United States Renal Data System. 2018 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 7.St Peter WL. Management of Polypharmacy in Dialysis Patients. Semin Dial. 2015;28(4):427–432. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manley HJ, Drayer DK, McClaran M, Bender W, Muther RS. Drug record discrepancies in an outpatient electronic medical record: frequency, type, and potential impact on patient care at a hemodialysis center. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(2):231–239. doi: 10.1592/phco.23.2.231.32079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindberg M, Lindberg P, Wikström B. Medication discrepancy: a concordance problem between dialysis patients and caregivers. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2007;41(6):546–552. doi: 10.1080/00365590701421363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ledger S, Choma G. Medication reconciliation in hemodialysis patients. CANNT J. 2008;18(4):41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung M, Jung J, Lau W, Kiaii M, Jung B. Best possible medication history for hemodialysis patients obtained by a pharmacy technician. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2009;62(5):386–391. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v62i5.826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan WW, Mahalingam G, Richardson RM, Fernandes OA, Battistella M. A formal medication reconciliation programme in a haemodialysis unit can identify medication discrepancies and potentially prevent adverse drug events. J Ren Care. 2015;41(2):104–109. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patricia NJ, Foote EF. A pharmacy-based medication reconciliation and review program in hemodialysis patients: a prospective study. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2016;14(3):785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson JS, Ladda MA, Tran J, et al. Ambulatory Medication Reconciliation in Dialysis Patients: Benefits and Community Practitioners’ Perspectives. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2017;70(6):443–449. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v70i6.1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Der Luit CD, De Jong IR, Ebbens MM, et al. Frequency of occurrence of medication discrepancies and associated risk factors in cases of acute hospital admission. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2018;16(4):1301. doi: 10.18549/PharmPract.2018.04.1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ong SW, Fernandes OA, Cesta A, Bajcar JM. Drug-related problems on hospital admission: relationship to medication information transfer. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(3):408–413. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raymond CB, Wazny LD, Sood AR. Standards of Clinical Practice for Renal Pharmacists. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013. Nov-Dec;66(6): 369–374. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v66i6.1302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicare and Medicaid Programs: Conditions for Coverage for End-Stage Renal Disease Facilities: Final Rule, 2013. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CFCsAndCoPs/downloads//esrdfinalrule0415.pdf Accessed December 11, 2019 [PubMed]

- 19. [December 11, 2019];End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Program Interpretive Guidance, Version 1.1. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/downloads/SCletter09-01.pdf Accessed.

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Center for Clinical Standards and Quality. CMS ESRD Measures Manual for the 2020 Performance Period. Draft Version 5.0, July 1, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/Measures-Manual-v50.pdf Accessed December 20, 2019

- 21.National Quality Forum (NQF), NQF-2988 Medication Reconciliation for Patients Receiving Care at Dialysis Facilities. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/NQF-2988-Patients-Receiving-Care-at-Dialysis-Facilities.pdf Accessed December 20, 2019

- 22.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) End-Stage Renal Disease quality Incentive Program (ESRD QIP) Payment Year (PY) 2022 Measure Technical Specifications. June 5, 2019. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/ESRDQIP/Downloads/PY-2022-Proposed-Rule-Technical-Specifications.pdf Accessed December 20, 2019

- 23.De Winter S, Spriet I, Indevuyst C, et al. Pharmacist- versus physician-acquired medication history: a prospective study at the emergency department. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redeer TA, Mutnick A. Pharmacist- versus physician-obtained medication histories. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2008;65:875–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mergenhagen KA, Blum SS, Kulger A, et al. Pharmacist- versus physician-initiated admission medication reconciliation: impact on adverse drug events. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2012;10:242–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lind KB, Soerensen CA, Salamon SA, et al. Consequence of delegating medication-related tasks from physician to clinical pharmacist in an acute admission unit: an analytical study. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2016;0:1–6. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-000990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang V, Coffman C, Stechuchak K, et al. Survival among Veterans Obtaining Dialysis in VA and Non-VA Settings. JASN. January 2019, 30 (1) 159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.St Peter WL. Improving medication safety in chronic kidney disease patients on dialysis through medication reconciliation. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17(5):413–419. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Hashar A, Al-Zakwani I, Eriksson T, et al. Whose responsibility is medication reconciliation: Physicians, pharmacists or nurses? A survey in an academic tertiary care hospital. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2015;25:52–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vogelsmeier A, Pepper G, Oderda L, et al. Medication Reconciliation: A qualitative analysis of clinicians’ perceptions. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 9 (2013) 419–430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Codd C, Marinusen D, Cardone K, et al. Preparing for implementation of a medication reconciliation measure for dialysis: Expanding the role of pharmacy technicians. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2020; 77:892–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Long J, Juntao Yuan M Poonawala R. An Observational Study to Evaluate the Usability and Intent to Adopt an Artificial Intelligence-Powered Medication Reconciliation Tool. Interactive Journal of Medical Research. 2016;5(2):e14 Doi: 10.2196/ijmr.5462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lesselroth B, Adams K, Church V, et al. Evaluation of Multimedia Medication Reconciliation Software: A Randomized Controlled, Single-Blind Trial to Measure Diagnostic Accuracy for Discrepancy Detection. Appl Clin Inform 2018;9:285–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gleason KM, Brake H, Agramonte V, Perfetti C. Medications at Transitions and Clinical Handoffs (MATCH) Toolkit for Medication Reconciliation (Prepared by the Island Peer Review Organization, Inc., under Contract No. HHSA2902009000 13C.) AHRQ Publication No. 11(12)-0059 Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Revised August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS) Toolkit. Available at: https://innovations.ahrq.gov/qualitytools/multi-center-medication-reconciliation-qualityimprovement-study-marquis-toolkit.

- 36.The National Forum of ESRD Networks. Medication Reconciliation Toolkit: Developed by the Forum of ESRD Networks’ Medical Advisory Council (MAC). https://esrdnetworks.org/resources/toolkits/mac-toolkits-1/medication-reconciliation-toolkit Accessed December 11, 2019

- 37.How-to Guide: Prevent Adverse Drug Events by Implementing Medication Reconciliation. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2011. (Available at www.ihi.org) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown S. Overcoming the pitfalls of medication reconciliation. Nurs Manage. 2012;43(1):15–17. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000409932.77213.9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarzynski EM, Luz CC, Rios-Bedoya CF, Zhou S. Considerations for using the ‘brown bag’ strategy to reconcile medications during routine outpatient office visits. Qual Prim Care. 2014;22(4):177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raghu TS, Frey K, Chang YH, Cheng MR, Freimund S, Patel A. Using secure messaging to update medications list in ambulatory care setting. Int J Med Inform. 2015;84(10):754–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2015.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riley KD, Wazny LD. Assessment of a fax document for transfer of medication information to family physicians and community pharmacists caring for hemodialysis outpatients. CANNT J. 2006;16(1):24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pai AB, Boyd A, Depczynski J, Chavez IM, Khan N, Manley H. Reduced drug use and hospitalization rates in patients undergoing hemodialysis who received pharmaceutical care: a 2-year, randomized, controlled study. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(12):1433–1440. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.12.1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manley HJ, Aweh G, Weiner DW, Jiang H, Miskulin DC, Johnson D, Lacson EK. Multidisciplinary Medication Therapy Management and Hospital Readmission in Patients Undergoing Maintenance Dialysis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2019, in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]