Abstract

Leishmaniasis, a major neglected tropical disease, affects millions of individuals worldwide. Among the various clinical forms, visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is the deadliest. Current antileishmanial drugs exhibit toxicity- and resistance-related issues. Therefore, advanced chemotherapeutic alternatives are in demand, and currently, plant sources are considered preferable choices. Our previous report has shown that the chloroform extract of Corchorus capsularis L. leaves exhibits a significant effect against Leishmania donovani promastigotes. In the current study, bioassay-guided fractionation results for Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL) were observed by spectroscopic analysis (FTIR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and GC–MS). The inhibitory efficacy of this β-sitosterolCCL against L. donovani promastigotes was measured (IC50 = 17.7 ± 0.43 µg/ml). β-SitosterolCCL significantly disrupts the redox balance via intracellular ROS production, which triggers various apoptotic events, such as structural alteration, increased storage of lipid bodies, mitochondrial membrane depolarization, externalization of phosphatidylserine and non-protein thiol depletion, in promastigotes. Additionally, the antileishmanial activity of β-sitosterolCCL was validated by enzyme inhibition and an in silico study in which β-sitosterolCCL was found to inhibit Leishmania donovani trypanothione reductase (LdTryR). Overall, β-sitosterolCCL appears to be a novel inhibitor of LdTryR and might represent a successful approach for treatment of VL in the future.

Subject terms: Mechanism of action, Natural products, Pharmacology, Biochemistry, Chemical biology, Computational biology and bioinformatics, Drug discovery

Introduction

Leishmaniasis, the vector-borne neglected tropical disease, is the second leading infectious disease after malaria. Approximately 350 million people are affected by leishmaniasis per year in 98 countries worldwide1. Leishmaniasis is caused by parasites of the genus Leishmania, which are transmitted to mammals by the bite of the vector, the female Phlebotominae sand fly. Leishmania parasites exist in two morphological stages: promastigotes, an elongated, flagellated, extracellular form, and amastigotes, an intracellular, round, nonflagellated form2. Major clinical manifestations of leishmaniasis comprise cutaneous, mucocutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis (VL). The most dreadful form of the disease is VL, which is caused by the species Leishmania donovani3.

The current treatment strategy for VL has various limitations and is still under debate due to the lack of suitable vaccines and inadequate chemotherapeutics. The foremost line of recommended therapeutics are pentavalent antimonials, such as sodium stibugluconate (Pentostam) and meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime), which emerged as the only remedies for the disease4. Regrettably, due to prolonged treatment strategies, these drugs are associated with high toxicity and increased incidences of drug resistance4. Although other drugs, such as pentamidine, miltefosine and amphotericin B, are very well known drugs for the treatment of VL, they exhibit unsatisfactory results due to toxic effects, high cost and, more importantly, drug resistance. Therefore, the search for economical alternative drugs with the weakest side effects seems imperative for VL treatment.

The history of classic plant-derived medicinal agents indicates their potential in modern medicine for their less lethal effects; hence, screening of many plant crude extracts can provide an array of novel biologically active plant products5. Thus, studies on natural products are now a priority in modern biological sciences6, and accordingly, innovation of novel, natural antileishmanial compounds has been escalated in the last few years7. Several plant-derived compounds have been investigated previously to evaluate their effects on various Leishmania spp.8. Accordingly, although our previous work showed the antiparasitic effects of the chloroform extract of Corchorus capsularis L. leaves on the Indian strain of L. donovani9, exploration of the leaf-derived active component(s) warrants great attention for the development of alternative remedies for VL. With regard to different disease manifestations, phytosterols have attracted attention for their beneficial role in health10. Among various phytosterols, β-sitosterol is predominant in plants and has significant dietary importance11,12. In recent years, the abundant plant sterol β-sitosterol has also been examined for its effect on various microbial infections, including parasitic diseases13–16. Plant-derived β-sitosterol has previously been tested on different species of Leishmania parasites, such as L. amazonensis17 and L. tropica18. A mixture of phytosterols containing stigmasterol and β-sitosterol has been reported to possess leishmanicidal activity against L. infantum chagasi19. Although the effect of these plant-derived β-sitosterols has been studied on various Leishmania spp., detailed study of plant β-sitosterol as an antiparasitic agent against L. donovani has not been performed until now.

The most promising method of effective drug discovery and development is to target the enzymes involved directly or indirectly in the parasite life cycle during the establishment of infection. Trypanothione reductase (TryR) is a key enzyme of Leishmania species that maintains redox homeostasis for the survival of the parasite20. Hence, considering the role of TryR, it could be assumed to be an appropriate drug target to treat L. donovani infection. During the last few years, medicinal use of natural lead components has been of growing interest for targeting different enzymes of parasites8. More importantly, plant products have also been shown to be excellent sources of TryR inhibitors21. Considering all of these aspects, the current investigation was undertaken to determine the effect of Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL) against L. donovani by targeting TryR for the design of a selective therapeutic against VL.

Results

Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL): bioassay-guided isolation and characterization

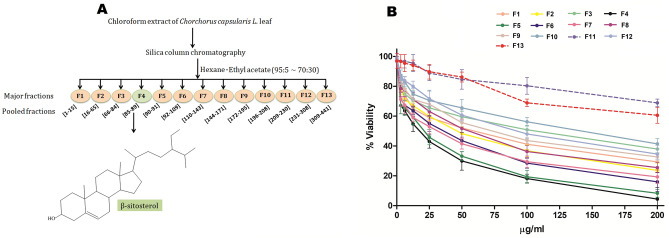

Major fractions (F1 to F13) were obtained according to the schematic presentation shown in Fig. 1A. The antipromastigote activity of all the fractions at doses ranging from 0 to 200 µg/ml was determined by calculating the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) using the MTT assay method (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table S1). The dose response curve (Fig. 1B) demonstrated that F4 is the most active fraction, having the maximum inhibitory effect with an IC50 value of 17.7 ± 0.43 µg/ml. Then, the lead fraction F4 (ethyl acetate:hexane = 7:93) was fully characterized on the basis of spectroscopic analysis (FTIR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR and GC–MS), the results of which are shown below, and the obtained lead phytocompound (F4) was found to be β-sitosterol.

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of bioassay-guided isolation of β-sitosterol from the chloroform extract of Corchorus capsularis L. leaves. (B) Determination of the antipromastigote activity of fractions (F1–F13). L. donovani promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) were treated individually with 13 fractions (F1–F13) at doses ranging from 0 to 200 µg/ml for 48 h, and the MTT assay was performed. F4 was found to be most active (IC50 = 17.7 ± 0.43 µg/ml), denoted by the black line, whereas the F11 and F13 fractions, denoted by dotted lines, exhibited IC50 values > 200 µg/ml. The results are expressed as the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments.

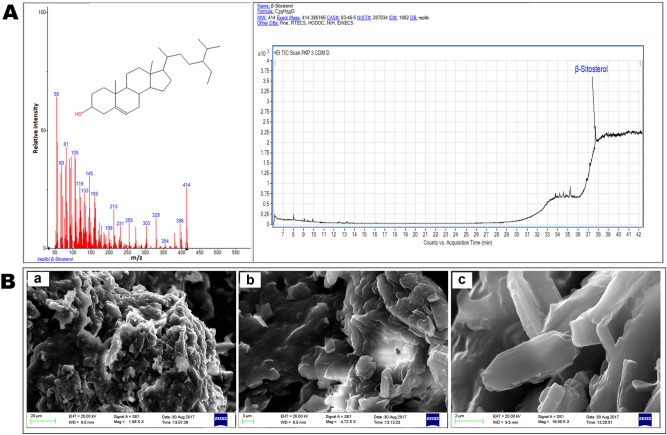

β-Sitosterol (C29H50O): White yellowish powder, mp 135 °C; FTIR (KBr) ν (cm−1): 3423.17, 2955.78, 2918.23, 2849.71, 1737.32, 1706.41, 1463.88, 1166.34 (Supplementary Fig. S1). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 5.340 (s, 1H), 3.559–3.505 (m, 1H), 2.351–2.201 (m, 4H), 2.022–1.949 (m, 3H), 1.840 (d, 3H, J = 10 Hz), 1.688–1.587 (m, 3H), 1.561–1.406 (m, 7H), 1.181–1.065 (m, 6H), 1.028–1.005 (m, 5H), 0.963–0.913 (m, 3H), 0.894–0.878 (m, 2H), 0.861–0.843 (m, 4H), 0.823–0.764 (m, 5H), 0.696–0.678 (m, 3H) (Supplementary Fig. S2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 179.17, 140.69, 121.75, 56.75, 56.04, 50.10, 45.80, 42.15, 39.76, 37.23, 36.49, 36.15, 34.03, 31.89, 31.51, 29.71, 29.68, 29.38, 29.09, 28.25, 26.03, 24.73, 24.30, 22.70, 21.07, 19.39, 19.03, 14.14, 11.85 (Supplementary Fig. S3). The molecular weight obtained by GC–MS was 414 Da (Fig. 2A). In the current study, the Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol was designated β-sitosterolCCL.

Figure 2.

(A) Mass spectrum of Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL) is shown in the left panel, and the right panel depicts the chromatogram. GC–MS analysis was performed with a gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies 7980A) equipped with a mass spectrometric system (7000, GC/MS triple quad). Agilent Mass Hunter software (Version B.50.00) was used for instrument control and data analysis. (B) Surface morphology analysis of β-sitosterolCCL by SEM imaging. SEM photographs: (a) scale bar, 20 μm; (b) scale bar, 3 μm; (c) scale bar, 2 μm.

Surface morphology analysis of β-sitosterolCCL

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging was performed to analyse the surface morphology, and the images obtained by SEM showed the flake-like structure of the isolated leaf compound, as depicted in Fig. 2B.

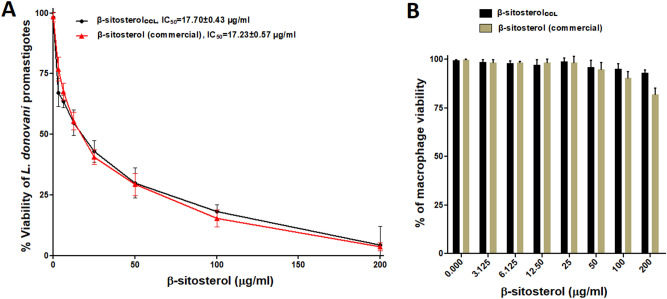

Screening of β-sitosterolCCL or commercial β-sitosterol as an antileishmanial agent by antipromastigote activity and cytotoxicity assays

The dose response curve obtained from the MTT assay demonstrated that commercial β-sitosterol (Abcam, USA) exhibits an inhibitory effect against the growth of L. donovani promastigotes with an IC50 value of 17.23 ± 0.57 µg/ml. Similarly, β-sitosterolCCL showed parasite growth inhibition at IC50 = 17.7 ± 0.43 µg/ml (Fig. 3A). These observations clearly demonstrate the analogous efficacy of β-sitosterolCCL compared with that of commercial β-sitosterol in killing L. donovani promastigotes.

Figure 3.

(A) Evaluation of antipromastigote activity. L. donovani promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) were treated with commercial β-sitosterol (Abcam, USA) (0–200 µg/ml) for 48 h, and the MTT assay was performed, and the IC50 was found to be 17.23 ± 0.57 µg/ml, denoted by the red line. β-SitosterolCCL, as shown by the black line (similar line used in Fig. 1B, IC50 = 17.7 ± 0.43 µg/ml), was used for comparison with the commercial standard. The results are presented as the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments. (B) Cytotoxicity against murine RAW 264.7 macrophages. The cytotoxic effects of β-sitosterolCCL and commercial β-sitosterol (Abcam, USA) were tested on macrophages (1 × 105/ml) with increasing concentrations (0–200 µg/ml) for 48 h, and an MTT assay was performed. The results expressed herein are from three independent experiments (mean ± S.E.).

β-SitosterolCCL affected 7.04 ± 0.38% of host cells at a high dose (200 µg/ml), but commercial β-sitosterol exhibited greater toxicity at a high dose, exhibiting 18.04 ± 0.75% killing of normal host cells (Fig. 3B). Thus, β-sitosterolCCL displays antileishmanial properties with negligible cytotoxicity even at a high doses. Therefore, β-sitosterolCCL seems to be more reliable than commercial β-sitosterol for subsequent evaluation of antileishmanial potency against L. donovani.

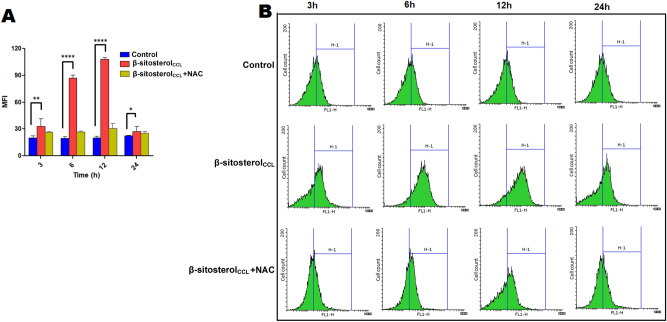

β-SitosterolCCL induces intracellular ROS production in promastigotes

Intracellular production of ROS is the central factor involved in triggering apoptosis in promastigotes22. Hence, we initially monitored the generation of intracellular ROS in β-sitosterolCCL-treated L. donovani promastigotes by using H2DCFDA, a cell-permeable dye. H2DCFDA is a nonfluorescent molecule, but once it enters cells, it is ultimately converted to the fluorescent DCF (2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein) by exposure to proper oxidants present within the cells. Therefore, the detected fluorescence of DCF is considered to be an indicator of the intracellular ROS level. Flow cytometry demonstrated that in the early hours of β-sitosterolCCL treatment, there was a gradual time-dependent increase in ROS production for up to 12 h, which triggered oxidative stress in β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites compared to the untreated control. Maximum production of ROS was found at 12 h, after which, ROS generation drastically decreased, reaching close to the level in control cells at 24 h. However, pre-treatment of promastigotes with the ROS quencher NAC (N-acetyl-l-cysteine) restrained the level of ROS generation in β-sitosterolCCL-treated cells to the level in control parasites at the same time points. A comparison of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the treated and control cells is shown in a bar graph (Fig. 4A), and shifting of the fluorescence intensity (FL1-H channel) in β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites compared to the control is also shown by a histogram (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Measurement of intracellular ROS generation in L. donovani promastigotes. ROS generation was monitored by flow cytometry using H2DCFDA at 3 h, 6 h, 12 h and 24 h. Elevated ROS level in β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites was observed compared to the control, whereas ROS generation in NAC-pre-treated promastigotes was found to be restrained to the level in control cells at each time point. Comparison of ROS generation in untreated, β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose)-treated and NAC (20 mM)-pre-treated promastigotes at different time points are represented in both the bar graph and histogram. (A) The bar graph is representative of three independent experiments, and statistical significance is calculated compared to the untreated control set by using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison test, where *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001 are considered statistically significant. (B) Histograms depict the shift of MFI as indicated by the H-1 region. Data were acquired in a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analysed in Flowing software (https://www.flowingsoftware.com), version 2.5.1, Finland.

β-SitosterolCCL alters the morphological structure of promastigotes

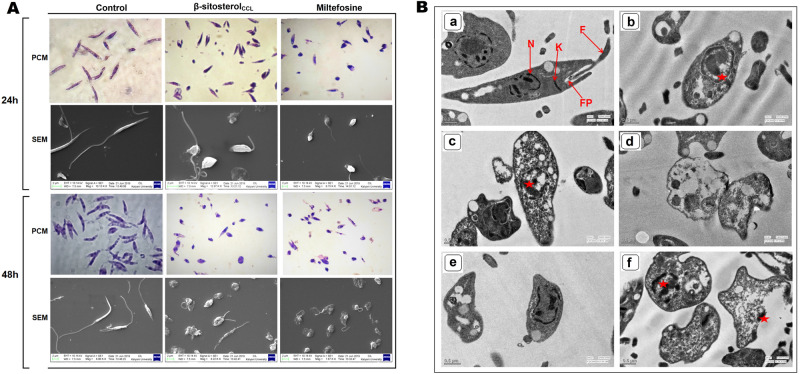

Changes in the morphological structure of promastigotes are the key indication of an apoptosis-like mode of cell death23. Henceforth, morphological deformities in β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes compared to the untreated cells were detected. For comparison, miltefosine (10 µM) was used as a positive control, showing distinct morphological alterations at both 24 h and 48 h. A snapshot captured by phase contrast microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Germany) showed that untreated parasites were structurally organized and elongated in shape with intact flagella after 24 h and 48 h. Similarly, β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites were morphologically atypical, exhibiting features such as roundness with shrinkage and shortening of flagella, compared to the untreated control parasites. This phase contrast microscopic data was also confirmed with SEM imaging of treated and untreated parasites at the same time points (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

(A) Morphological study of L. donovani promastigotes. Phase contrast microscopy (PCM) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) results depicting morphological alterations in β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose)-treated promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) for 24 h and 48 h compared to control cells. SEM scale bars = 2 μm. (B) TEM results showing ultrathin sections of L. donovani promastigotes. Promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) were treated with β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose) for 24 h and 48 h. (a) Untreated control, (b) β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes for 24 h, (c,d) β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes for 48 h, (e) miltefosine (10 µm)-treated promastigotes for 24 h, (f) miltefosine (10 µm)-treated promastigotes for 48 h. N, nucleus; K, kinetoplast; F, flagellum; FP, flagellar pocket. Scale bar = 0.5 μm. In treated cells, the star (red) indicates the vacuolated nucleus.

β-SitosterolCCL causes ultrastructural changes in promastigotes

Regarding ultrastructural alterations, β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites exhibited notable deformities of internal cellular organelles, such as vacuolated nuclei, distortion of flagellar pockets, and disorganization of mitochondria and kinetoplasts at 24 h and 48 h. However, untreated control parasites displayed normal morphological structures with well-organized intracellular organelles consisting of intact flagellar pockets with flagella, nuclei at central positions and kinetoplasts at the proper location (Fig. 5B). In parallel, miltefosine (10 µm) was used as a positive control for comparison of ultrastructural deformities as observed in the β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites at 24 h as well as 48 h.

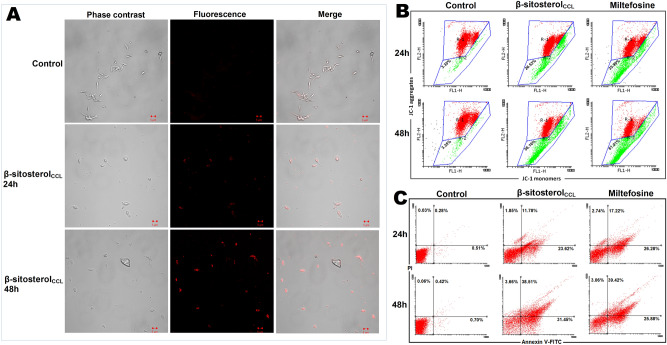

β-SitosterolCCL triggers lipid body accumulation in promastigotes

Excess accumulation of intracellular lipid droplets is a key characteristic of cellular stress and triggers apoptosis in parasites24. Therefore, while searching for apoptotic events in parasites caused by β-sitosterolCCL, we were greatly concerned with evaluating the enhanced accumulation of lipid bodies in treated L. donovani promastigotes by using the common fluorescent marker Nile Red, which generally stains intracellular lipid droplets. Upon β-sitosterolCCL treatment for 24 h and 48 h, superfluous lipid droplets were observed to be randomly distributed throughout the cytoplasm of promastigotes, in contrast to the untreated control parasites (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6.

(A) Superfluous lipid body detection in L. donovani promastigotes. Promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) treated with β-sitosterolCCL for 24 h and 48 h; images were obtained by LSM510-META confocal microscopy after Nile Red staining. Phase contrast, fluorescence, and phase contrast-fluorescence merged images are representative of three independent experiments. (B) Flow cytometric determination of mitochondrial membrane depolarization. Promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) treated with β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose) for 24 h and 48 h followed by JC-1 staining. The fluorescence intensity of JC-1 was measured, and histograms (snapshot) of β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites were compared with control and miltefosine (10 µM)-treated cells for 24 h and 48 h. Red (R-1 region) and green (R-2 region) depict high and low mitochondrial membrane potential, respectively. The snapshots are representative of one of three independent experiments. Data were acquired in a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analysed in Flowing software (https://www.flowingsoftware.com), version 2.5.1, Finland. (C) Determination of externalization of phosphatidylserine by flow cytometry. Promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) were treated with β-sitosterolCCL followed by annexin V-FITC and PI staining. Respective dot plots of β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites are represented along with control and miltefosine (10 µM)-treated cells for 24 h and 48 h. Data were acquired in a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analysed in Flowing software (https://www.flowingsoftware.com), version 2.5.1, Finland.

β-SitosterolCCL causes mitochondrial membrane depolarization in promastigotes

Elevated production of intracellular ROS causes oxidative stress inside promastigotes and subsequently induces mitochondrial membrane depolarization, a major indication of apoptosis25. Therefore, the significant effect of β-sitosterolCCL on ROS production made us curious to observe its simultaneous effect on mitochondrial transmembrane potential. Therefore, measurement of mitochondrial membrane depolarization was carried out in promastigotes using the dye JC-1 (5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′ tetraethylbenzimidazolcarbocyanine iodide). The dye usually forms aggregates in mitochondria after entering cells. However, in apoptotic cells, aggregated JC-1 is released from mitochondria to the cytoplasm as a monomer. Consequently, aggregated JC-1 at higher potential emits red fluorescence, whereas at lower membrane potentials, JC-1 remains as a monomer within the cytoplasm and emits green fluorescence26. Thus, the shift in the cell population towards green fluorescence, as observed by the FACS study, indicates mitochondrial membrane potential depolarization. In the JC-1 assay, FACS data showed that β-sitosterolCCL treatment induced the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential in promastigotes by 26.53% and 56.16% at 24 h and 48 h, respectively (Fig. 6B). Correspondingly, in miltefosine (10 µm)-treated promastigotes, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential was perceived by 35.99% (24 h) and 61.01% (48 h) of the promastigotes.

β-SitosterolCCL induces externalization of phosphatidylserine in promastigotes

Externalization of phosphatidylserine to the outer surface of the plasma membrane is the core indication of apoptosis in unicellular eukaryotic cells27. Phosphatidylserine exposure is usually analysed by flow cytometry through a dual staining process with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (annexin V-FITC) and propidium iodide (PI)27. In the early stage of cellular apoptosis, when the plasma membrane loses its symmetry, membrane phospholipids are eventually translocated from the inner to outer plasma membrane, and annexin V-FITC rapidly binds with high affinity to the phosphatidylserine exposed to apoptotic cells (early and late). PI selectively binds to DNA in necrotic cells in which membrane integrity is already interrupted, and PI eventually discriminates apoptotic cells from necrotic cells28. Thus, the different labelling patterns of annexin V-FITC/PI in the dot plot describe various conditions of cells, which are as follows: annexin V-FITC-negative and PI-negative cells are considered viable, annexin V-FITC-positive and PI-negative cells are considered early apoptotic cells, and annexin V-FITC-positive and PI-positive cells are considered late apoptotic cells, whereas annexin V-FITC-negative and PI-positive cells are considered necrotic cells. Therefore, to determine the apoptotic effect of β-sitosterolCCL in comparison to the effect in untreated control and positive control (miltefosine treated), L. donovani promastigotes were double stained with both annexin V-FITC and PI for subsequent flow cytometric analysis. As a result, 26.28% of cells found in the lower-right quadrant were in the early apoptotic phase at 24 h, and 17.22% of cells in the upper-right quadrant were in the late apoptotic stage at the same time point upon miltefosine (10 µM) treatment. After 48 h of miltefosine treatment, 25.88% and 39.42% parasites were detected in the early and late apoptotic stages, respectively, compared to the untreated control parasites (Fig. 6C). Similarly, β-sitosterolCCL treatment for 24 h resulted in 23.62% and 11.78% early and late apoptotic cells, respectively. Increasing the exposure time of β-sitosterolCCL to 48 h increased the amounts of early and late apoptotic cells by 31.45% and 38.51%, respectively (Fig. 6C). Therefore, taken together, these flow cytometry data undoubtedly indicate β-sitosterolCCL to be a potent apoptosis-triggering agent in L. donovani promastigotes.

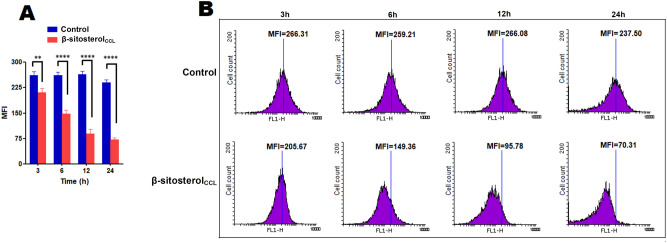

β-SitosterolCCL decreases non-protein thiol levels and trypanothione reductase (TryR) activity in promastigotes

Thiols play a key role in protecting parasites against ROS-mediated oxidative stress29, and thus, depletion of non-protein thiols could be considered an appropriate focus for drug targeting. In addition, trypanothione reductase (TryR), an indispensable enzyme of kinetoplastid parasites, participates in their unique thiol-redox metabolism20. Therefore, the ROS-mediated induction of apoptosis by β-sitosterolCCL made us interested in examining the trypanothione reductase activity and intracellular levels of non-protein thiols. The level of the thiols was monitored flow cytometrically in β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes by using the well-known dye 5-chloromethylfluorescein-diacetate (CMFDA). The dye penetrates the cells and usually binds to non-protein thiols and is ultimately converted to a fluorescent thioether30. Therefore, the detected fluorescence reflects the level of total non-protein thiols present within the parasites. In β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes, a gradual time-dependent decrease in fluorescence intensity was noticed by flow cytometry for up to 24 h compared to the intensity in the control. A comparison of the MFI values of β-sitosterolCCL-treated and control parasites is shown in a bar graph (Fig. 7A) and histogram (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Measurement of intracellular non-protein thiols in promastigotes. Promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) were treated with β-sitosterolCCL, and fluorescence intensity was measured after CMFDA staining at various time points, i.e., 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h. (A) The bar graph depicts the MFI values of three independent experiments, and statistical significance was determined with respect to the control by using a t-test, where **p < 0.01 and ****p < 0.0001 were considered statistically significant. (B) Histograms depicting the reduction of MFI in β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites compared to the control at every time point. Data were acquired in a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analysed in Flowing software (https://www.flowingsoftware.com), version 2.5.1, Finland.

Since β-sitosterolCCL causes a reduction in the levels of thiols in Leishmania promastigotes, TryR inhibition by this component was initially performed in soluble extracts of L. donovani promastigotes. The percentage of inhibition of this enzyme in parasite extracts was calculated in terms of the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm, indicating NADPH oxidation. Thus, the optical density itself indicates the consumption of NADPH by TryR. The control lacking any inhibitor was considered as having 100% TryR activity. However, the presence of β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose) inhibited NADPH consumption by TryR by 52.77 ± 1.04% in parasite extracts compared to the control (Supplementary Fig. S4). To validate the observation, commercial β-sitosterol (Abcam, USA) was also used, which showed a similar inhibitory effect as that of β-sitosterolCCL (Supplementary Fig. S4).

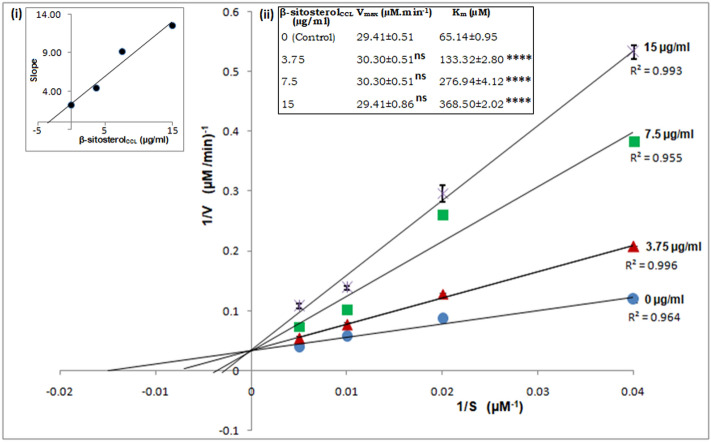

β-SitosterolCCL competitively inhibits Leishmania donovani trypanothione reductase (LdTryR)

To determine the type of inhibition of L. donovani trypanothione reductase (LdTryR) exhibited by β-sitosterolCCL, an enzyme kinetics study was performed on recombinant LdTryR. The Lineweaver–Burk plot obtained from the kinetics study showed a gradual increase in apparent Km with increasing β-sitosterolCCL concentration without any effect on Vmax. As a result, the inhibition of LdTryR by β-sitosterolCCL appeared to be competitive, and the inhibition constant (Ki) of β-sitosterol was found to be 3.5 µg/ml (8.43 µM) (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Kinetic analysis of LdTryR inhibition. Lineweaver–Burk plot of LdTryR inhibition by β-sitosterolCCL represents the competitive type. T(S)2 was used as the substrate at 25, 50, 100, and 200 µM, and the concentrations of β-sitosterolCCL were 0, 3.75, 7.5 and 15 µg/ml. S, substrate concentration (µM); V, reaction velocity (µmol/min); R2, coefficient of determination. The graph in the inset (i) is the secondary replot of the slope of the Lineweaver–Burk plots versus various concentrations of β-sitosterolCCL, and the value of the inhibition constant (Ki) was calculated as 3.5 µg/ml (8.43 µM). The inset (ii) depicts the kinetic parameters (Vmax and Km) of LdTryR inhibition in the presence of different concentrations of β-sitosterolCCL. The statistical significance of the Vmax and Km values was calculated in comparison to the control by using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison tests. The values are statistically significant, where **** indicates p < 0.0001; “ns” indicates values that are not statistically significant. Herein, values are shown as the mean ± S.D. of three independent studies.

Molecular docking-based binding interactions of β-sitosterolCCL with Leishmania donovani trypanothione reductase (LdTryR)

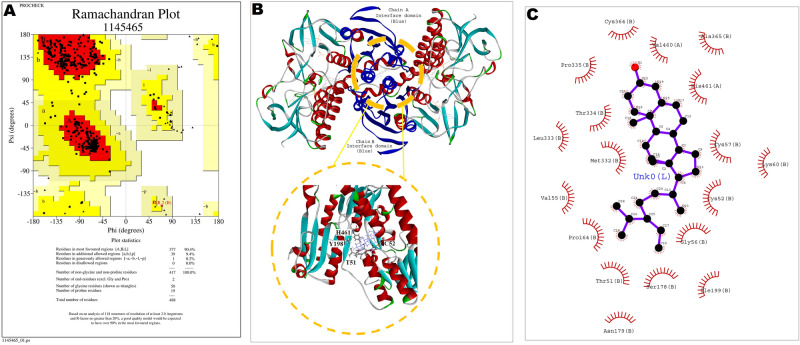

Trypanothione reductase (TryR), an NADPH-dependent enzyme, is unique to kinetoplastid parasites, including Leishmania. The key role of TryR in redox metabolism has made it an interesting option for the design of advanced antileishmanial drugs20,31. To better understand the binding interactions of the ligand β-sitosterolCCL (Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol), molecular docking simulations were performed using the three-dimensional structure of the ligand with L. donovani trypanothione reductase (LdTryR). Due to the lack of a crystal structure for LdTryR, homology modelling was performed to generate a three-dimensional model of the protein LdTryR. The homology model of LdTryR was built using the crystallographic structure of TryR from Leishmania infantum in complex with TRL156 (PDB Code: 6I7N, chain B), which was used as the template because it shared 98% sequence identity with the LdTryR protein. The modelled structure of LdTryR was superimposed on the crystal structure of the template, and the RMSD of the superimposition was found to be 0.25 Å (Supplementary Fig. S5A). The validation of stereo-chemical qualities of the modelled structure of LdTryR was estimated by the PROCHECK program, and 90.4% of the amino acid residues were in the most favoured region of the Ramachandran plot (Fig. 9A). The structural qualities of the modelled protein were again analysed by Verify3D, and the model passed the criteria of Verify3D; thus, the constructed LdTryR structure was considered a good quality model. Then, the modelled protein (Supplementary Fig. S5B) was docked to the ligand to obtain the three-dimensional (3D) docking conformation with a close-up view of the binding interactions of LdTryR and the ligand, as shown by the circle in Fig. 9B. In this docking analysis, the list of amino acid residues of dimeric LdTryR and their binding energy values with the ligand β-sitosterolCCL are presented in tabular form (Supplementary Table S2), and the total ΔG value of the binding interactions was found to be − 119.4 kcal/mol. The stability of the docked complex was determined for up to 100 ns. Some of the fluctuating amino acid residues identified herein were Pro 42, Asp 84, Asp142, Gly168, Asp 272, Gly 352, Ser 464, and Ser 488 (Supplementary Fig. S5C). The amino acids of LdTryR involved in the binding interactions with the ligand β-sitosterolCCL are shown as two-dimensional (2D) representations (Fig. 9C), which indicate that Val 460 and His 461 were from chain A and Cys 364, Ala 365, Cys 57, Lys 60, Cys 52, Gly 56, Ser 178, Asn 179, Ile 199, Thr 51, Pro 164, Val 55, Met 332, Leu 333, Thr 334, and Pro 335 were from chain B of LdTryR.

Figure 9.

(A) Validation of the modelled structure using a Ramachandran plot by PROCHECK analysis. Ramachandran plot showing that 90.4% of amino acid residues are distributed in the allowed region with no amino acids in the disallowed region, indicating good stereochemical fitness of the generated model. (B) 3D conformation of the LdTryR-β-sitosterolCCL docked complex, where the circle indicates a close-up view of the binding interactions. (C) Ligplot (2D representation) of the docked conformation of LdTryR-β-sitosterolCCL represents adjoining interaction residues of LdTryR denoted by an eyelash mark.

Discussion

Plant-derived natural products possess diverse pharmacological activities and consequently are an attractive resource for the development of advanced chemotherapeutics to treat a wide range of disease conditions, including microbial infections32. For the last few years, plant sources have also been reported to be very important in Leishmania research8. Existing drugs against visceral leishmaniasis exhibit several limitations, such as the emergence of resistance, toxicity and high cost33,34. Therefore, in the search for economically feasible antileishmanial agents with better efficacy and low toxicity, plant sources are highly prioritized. In this regard, our previous work on the antileishmanial activity of C. capsularis L. leaf extract revealed its efficacy against L. donovani promastigotes9; therefore, isolation of the natural lead component seems to be significant for exploration of its therapeutic utility in the treatment of VL. Thus, based on the antileishmanial property9 and relatively low cytotoxicity of C. capsularis L. leaf extract (see Supplementary Method, Results, Fig. S6), the current work was undertaken with the aim of identifying bioactivity-based lead compounds that may play a role in killing parasites. The subsequent bioassay-guided fractionation process resulted in the isolation of a major phytosterol, β-sitosterol, from Corchorus capsularis L. leaves (β-sitosterolCCL).

In many earlier reports, the medicinal value of plant-derived β-sitosterol has been demonstrated, and the role of β-sitosterol as an antimicrobial agent has also been revealed in the treatment of various infectious diseases13,14. β-Sitosterol from a variety of plant sources is applied in the treatment of many parasitic diseases15,16. Plant-derived β-sitosterol has also been studied against different forms of leishmaniasis; for example, phytosterols (stigmasterol + β-sitosterol) isolated from Musa paradisiaca fruit peel have been tested for antileishmanial properties in vitro by studying growth inhibition of L. infantum chagasi promastigotes and amastigotes19. Similarly, β-sitosterol isolated with other components from Sassafras albidum stem bark was studied against Leishmania amazonensis, where the β-sitosterol was found to be least effective against the promastigotes, which was evident from its highest IC50 value in comparison to that of the other isolated products17. Furthermore, although the leishmanicidal effect of β-sitosterol from Ifloga spicata showed apoptosis-type killing of L. tropica promastigotes, the detailed mechanism of apoptosis is unclear18. Previously, β-sitosterol isolated from Thalia geniculata was also tested against L. donovani amastigotes (strain MHOM/ET/67/L82), but no significant activity of β-sitosterol was documented16. Therefore, despite the many studies on the effect of plant-derived β-sitosterol on various forms of leishmaniasis, the mechanisms by which the compound kills the parasites remain unclear. On the basis of previous reports, it could be suggested that although the effect of different plant-derived β-sitosterols has been examined on various Leishmania spp., the effectiveness varies among different Leishmania species and strains16–19,35. The discrepancy in the efficacy of drugs depends on the phenotypic variability of different species or strains, clinical appearances and geographical origin36,37. Certain antileishmanial drugs have also been reported to exhibit species- and strain-specific efficiency37–40. Additionally, various plant-derived secondary metabolites have been shown to exhibit target-specific activity against parasites15. Therefore, considering these aspects, the present investigation of Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL) against the Indian strain of L. donovani promastigotes [(MHOM/IN/1983/AG83)] seems very reasonable and unique.

As β-sitosterol is available commercially, during our investigation of the antileishmanial properties of β-sitosterolCCL, it was also of interest to evaluate the efficacy of commercial β-sitosterol on L. donovani promastigotes. Therefore, commercial β-sitosterol was initially compared herein with β-sitosterolCCL in terms of its antileishmanial properties and cytotoxicity. Although both β-sitosterolCCL and commercial β-sitosterol exhibited potent antileishmanial activity, β-sitosterolCCL was less toxic than commercial β-sitosterol. Similar observations have also been reported previously, showing that plant extracts or plant-derived components are safer and more efficient than any synthetic drugs against parasitic diseases18. As a result, the current investigation on the natural lead component β-sitosterol from the commonly available edible plant C. capsularis L. focused on β-sitosterolCCL as a novel agent for elucidating the cell death mechanism in L. donovani.

In the present study, β-sitosterolCCL initially led to the appearance of major features of apoptosis, such as the formation of intracellular ROS and, subsequently, an atypical morphology of L. donovani promastigotes with alterations in internal organelles. Similar morphological and ultrastructural changes were observed during apoptotic death of L. donovani promastigotes treated with clerodane diterpene (K-09) obtained from Polyalthia longifolia leaves24. Lipid droplets are very special, dynamic and complex organelles that play a key role in regulating lipid metabolism in unicellular protozoan parasites41. Surplus cytoplasmic accumulation of these lipid droplets is also regarded as a symbolic feature of apoptotic cells42. A report suggests that the dibenzylideneacetone A3K2A3 exerts leishmanicidal activity through the excess accumulation of lipid bodies within the parasites43. An elevated number of lipid droplets upon clerodane diterpene K-09 exposure was also noted in L. donovani parasites24. Generally, impeding lipid metabolism causes excess production of lipid precursors that accumulate in the form of lipid bodies inside cells and provoke cell death24,42. Correspondingly, in the current study, the antiparasitic nature of β-sitosterolCCL was also observed as enhanced accumulation of lipid bodies in β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites, which ultimately led to parasite killing due to probable alteration of lipid metabolism.

Leishmania parasites possess a single mitochondrion that plays an essential role in the survival of parasites by maintaining homeostasis; thus, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential could be considered a very striking characteristic of cell death by means of apoptosis22,23. Interestingly, an appreciable time-dependent decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential was noticed in β-sitosterolCCL-treated parasites and consequently provided an excellent indication of apoptosis. Subsequently, depolarization of the mitochondrial membrane potential allowed us to explore the apoptosis promotion capability of this β-sitosterolCCL in L. donovani promastigotes. Apoptosis is a common physiological phenomenon that leads cells towards death27. In higher eukaryotic unicellular organisms, apoptosis is represented by externalization of phosphatidylserine from the inner leaflet to the outer surface of the plasma membrane. Interestingly, increased exposure of phosphatidylserine was similarly noticed in L. donovani promastigotes after β-sitosterolCCL treatment, which further confirms the mode of parasite killing exhibited by this natural lead component.

Furthermore, the ROS-mediated apoptosis-like programmed cell death events in promastigotes caused by β-sitosterolCCL exposure inspired us to explore the effect of the compound on non-protein thiols, which play an important role in protecting parasites under oxidative stress condition29,30. Fascinatingly, in the current study, significant depletion of non-protein thiol levels was also noticed in L. donovani promastigotes upon β-sitosterolCCL treatment. Thus, β-sitosterolCCL causes redox imbalance situations with increased ROS production and decreased antioxidant-like thiol levels in L. donovani promastigotes followed by apoptosis. Moreover, the viability and infectivity of Leishmania parasites generally depend on some key enzymes, the major enzyme among which is a redox-maintaining enzyme, trypanothione reductase (TryR). In general, the redox balance in Leishmania is regulated by TryR, which provokes a cascade of events via the reduction of trypanothione disulphide [T(S)2] to the dithiol form [T(SH)2] by neutralization of ROS20. Thus, the antileishmanial function of β-sitosterolCCL targeting the enzyme TryR appears very imperative and relevant in the current study. Consequently, an enzymatic assay was performed, which showed that β-sitosterolCCL significantly inhibits TryR activity in soluble extracts of L. donovani promastigotes. Therefore, a subsequent enzyme kinetics study on recombinant LdTryR was performed with β-sitosterolCCL and clearly demonstrated that β-sitosterolCCL is an efficient competitive inhibitor of LdTryR. This further confirms that β-sitosterolCCL acts as a potent antileishmanial agent by competitively inhibiting the enzyme LdTryR. Although many synthetic compounds are also reported to inhibit the parasitic trypanothione reductase enzyme in a competitive manner21,44,45, the inhibition of LdTryR by β-sitosterol obtained from C. capsularis L. leaves is the first report of an efficient antileishmanial agent. Therefore, the significant inhibitory effect of β-sitosterolCCL against LdTryR led us to check the binding affinity of the compound with the enzyme with the help of molecular docking simulation.

Molecular modelling, a computer-assisted tool, has emerged as an attractive platform for better understanding drug design and is widely used to predict the preferred binding orientation of pharmacologically active molecules (ligands) with biological macromolecules46. Trypanothione reductase (TryR) is an NADPH-dependent homodimer that comprises the cofactor FAD bound to each subunit and helps in electron transfer from NADPH to oxidized trypanothione through the prosthetic group, FAD and a redox-active cysteine disulphide residue20,47. Previously, many phytocompounds and synthetic compounds have been reported to dock with TryR from different Leishmania spp.18,20,21. Docking studies have been performed between TryR from L. infantum (PDB ID 4APN) and β-sitosterol18. However, the efficiency of plant-derived β-sitosterols in the binding of L. donovani trypanothione reductase has yet to be studied. Hence, we used molecular docking to investigate the binding capacity of β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL) with trypanothione reductase of L. donovani. The X-ray crystallographic structure of L. donovani trypanothione reductase (LdTryR) is not well documented21. Therefore, we employed homology modelling to generate the three-dimensional structure of LdTryR using the X-ray crystallographic structure of TryR from Leishmania infantum in complex with TRL156 (PDB Code: 6I7N, chain B) as a template. The sequence identity between LdTryR and the template was 98%. Then, we made a structural comparison between the modelled structure of LdTryR with the template 6I7N, chain B by structurally aligning their C-α backbone atoms. The root mean squared deviation (RMSD) between the backbones of the proteins was found to be 0.25 Å, which indicates a significant structural similarity between the modelled LdTryR and the template 6I7N, chain B. Ultimately, the modelled structure of LdTryR was used to dock with the ligand β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL) in the presence of FAD (cofactor) and NADPH; the stability of the molecular interaction was also established from the ΔG value. Next, we tried to compare the distribution of the active site amino acid residues of LdTryR with the same proteins from other members of the Leishmania and Trypanosoma families. For that purpose, we used the amino acid residues of the following sets of proteins:

LiTryR from Leishmania infantum TryR.

TcTryR from Trypanosoma cruzi TryR.

LbTryR from Leishmania braziliensis TryR.

We compared the amino acid sequences of the above mentioned proteins by a multiple sequence alignment method and identified the conserved active site amino acid residues in the proteins (Supplementary Fig. S7). These residues are conserved in all species. In our model, all these residues were also found to be involved in binding interactions, which take place in and around the active sites. Therefore, the in silico interaction study again validates the observations of the inhibitory activity of β-sitosterolCCL targeting TyrR of L. donovani promastigotes.

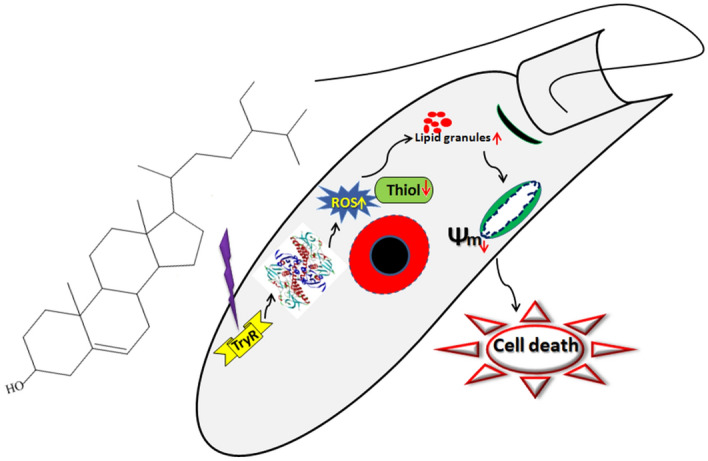

Overall, the antileishmanial activity of β-sitosterolCCL against L. donovani promastigotes exhibits very specific apoptotic features by targeting LdTryR, as depicted in the proposed model (Fig. 10). Thus, the present work might provide an efficient way to use Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL) as an alternative novel therapeutic agent against visceral leishmaniasis in the future.

Figure 10.

Proposed model of C. capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL)-mediated inhibition of LdTryR in parasite killing.

Conclusion

The present investigation introduces Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL) as a novel antileishmanial agent that competitively inhibits Leishmania donovani trypanothione reductase. Overall, the antiparasitic efficiency and the ability of this phytosterol to block one of the most crucial parasitic enzymes emphasize its proficiency as a strong candidate for treatment of visceral leishmaniasis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The Indian strain of Leishmania donovani (MHOM/IN/1983/AG83) promastigotes was cultured at 22 °C in medium 199 (Sigma-Aldrich) with 100 U/ml penicillin (Gibco) and 100 mg/ml streptomycin (Gibco) with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated foetal calf serum (Gibco). The murine macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 was also maintained in RPMI 1640 at 37 °C in 5% CO248.

Bioassay-guided fractionation and isolation of compounds

Chloroform extract of Corchorus capsularis L. leaves was subjected to silica gel (Merck, pore size 60–120) column chromatography and eluted with different step gradients of hexane–ethyl acetate by increasing the proportion of ethyl acetate. A total of 441 fractions of 50 ml each were collected. Based on thin layer chromatography (TLC) (Merck) profiles, fractions were pooled to obtained thirteen major fractions (F1 to F13). These fractions (F1-F13) were evaporated to dryness on rotary evaporator (Buchi, Switzerland).

The fractions (F1-F13) were screened against L. donovani promastigotes, testing for viability, by the MTT assay9. Log-phase promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) were seeded in 96-well plates (BD falcon) and treated separately with these fractions (0–200 µg/ml) for 48 h. Next, MTT was added, and the plate was incubated for 6 h at 37 °C. Then, viable cells were estimated by conversion of MTT to formazan at 570 nm in an iMark Microplate Reader (Bio-Rad). The IC50 value of each fraction was calculated by GraphPad Prism software (version 5).

Characterization of Corchorus capsularis L. leaf-derived β-sitosterol (β-sitosterolCCL)

FTIR analysis of the isolated lead compound was carried out to identify the existing functional groups. A thin disc of the sample was prepared by using a KBr pellet, and the spectral data were recorded by FTIR spectrometry (Perkin Elmer)49. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were scanned with a Bruker Avance spectrometer at 400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively, by using CDCl3 as the solvent system49. GC–MS analysis was performed with a gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies 7980A) equipped with a mass spectrometric system (7000, GC/MS triple quad). An HP-5MS column (30 m length, 0.25 mm I.D., film thickness 0.25 μm) was employed50. Agilent Mass Hunter software (Version B.50.00) was used for instrument control and data analysis.

Surface morphology analysis of β-sitosterolCCL

The compound was dried under vacuum for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) imaging. Images of the surface morphology of the compound were then obtained by SEM (ZEISS EVO LS 10).

Antipromastigote activity and cytotoxicity assay of β-sitosterolCCL and commercial β-sitosterol

To check the inhibitory effect of commercial β-sitosterol on the growth of L. donovani promastigotes, an MTT assay was performed as described previously9. Promastigotes (1 × 107/well) were treated individually with β-sitosterolCCL and commercial β-sitosterol (Abcam, USA) (0–200 µg/ml) for 48 h. The IC50 value was determined from a graphical representation (GraphPad Prism software, version 5).

Similarly, cytotoxicity was tested on RAW 264.7 macrophages (1 × 105/ml) by an MTT assay with β-sitosterolCCL and commercial β-sitosterol. Macrophages were treated with both the β-sitosterols at a dose of 0 to 200 µg/ml for 48 h. The percentage of host cells affected by the compounds was calculated through graphical exploitation by using GraphPad Prism software (version 5).

Measurement of ROS in β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes

Leishmania donovani promastigotes (1 × 107/ml) were treated with β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose) for 3 h, 6 h, 12 h and 24 h. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and incubated with the cell-permeable probe 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA)51 for 30 min. One set of cells was pre-treated with 20 mM ROS quencher (NAC; Sigma–Aldrich) at the same time points. The intensity of the fluorescence signal was then acquired with a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analysed by Flowing software (version 2.5.1, Finland)52.

Parasite morphology analysis of β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes

Promastigotes were treated with β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose) for 24 h and 48 h. Then, treated and untreated cells were fixed in methanol and stained with Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich). Subsequently, images were obtained under a Meiji (ML 2955) light microscope (100× objective). For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), fixation of cells was performed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde for 3 h at room temperature, and the cells were left overnight at 4 °C53. Then, the samples were dehydrated with an increasing gradient of ethanol washing solution and imaged under a scanning electron microscope (ZEISS EVO LS 10). Herein, miltefosine (10 µm) was used as a positive control.

Ultrastructural study of β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes

Promastigotes were treated with β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose) for 24 h and 48 h. Cells were then fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). Then, samples were prepared for TEM, and ultrastructural imaging was performed using a Tecnai G2 20 S-Twin transmission electron microscope at SAIF, AIIMS, New Delhi54.

Detection of lipid droplet accumulation in β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes

Excess accumulation of lipid bodies within parasites was detected by using Nile Red dye55. Briefly, promastigotes (1 × 107 cells/ml) were treated with β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose) at 24 h and 48 h. Cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml Nile Red for 30 min in the dark and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.2). Parasites were then imaged under LSM510-META confocal microscopy (Carl Zeiss, Germany)56 at 480 nm for excitation and 530 nm for emission.

Determination of mitochondrial membrane potential in β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes

The mitochondrial membrane potential in treated and untreated parasites was assessed flow cytometrically by using the cell-permeable dye JC-122. Promastigotes (1 × 107 cells/ml) were treated with β-sitosterolCCL for 24 h and 48 h. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated with JC-1 (BD Biosciences) for 15 min at 37 °C according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Then, data were acquired in a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analysed in Flowing software (version 2.5.1, Finland).

Detection of phosphatidylserine externalization in β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes

Promastigotes (1 × 107 cells/ml) were treated with an IC50 dose of β-sitosterolCCL for 24 h and 48 h. The washed cell pellet was resuspended in 1× binding buffer. Subsequently, the samples were incubated in the dark for 20 min after the addition of annexin V-FITC and PI22. Data acquisition and analysis were performed in a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and Flowing software (version 2.5.1, Finland), respectively.

Measurement of non-protein thiols in β-sitosterolCCL-treated promastigotes

Promastigotes (1 × 107 cells/ml) were treated with an IC50 dose of β-sitosterolCCL at 3 h, 6 h, 12 h and 24 h. After treatment, the cells were incubated with 10 μM CMFDA (Molecular Probes) in the dark for 30 min30. The samples were acquired in a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer and analysed in Flowing software (version 2.5.1, Finland).

Trypanothione reductase assay

Soluble extract of L. donovani promastigotes was obtained by resuspending the washed pellet in buffer containing 40 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and 1 mM EDTA57. The cell suspension was then lysed in a Dounce homogenizer and centrifuged at 12,000×g for 15 min. The supernatant collected was considered the soluble fraction containing trypanothione reductase. Then, the assay was performed by incubating the soluble protein fraction (1 mg/ml) for 10 min with β-sitosterolCCL (IC50 dose). Then, the reaction was initiated by the addition of NADPH (0.1 mM) in HEPES (40 mM) and EDTA 1 (mM) plus 100 mM substrate (trypanothione disulphide, Sigma-Aldrich). Herein, commercial β-sitosterol (Abcam, USA) was also tested in parallel, and a positive control set was made by incubation with clomipramine (10 µM), a known TryR inhibitor31. TryR activity was measured in a spectrophotometer (Hitachi, Japan) by measuring NADPH consumption at 340 nm. The percentage of inhibition was eventually calculated based on a decrease in optical density20,57.

Enzyme kinetics study of the effect of β-sitosterolCCL on recombinant Leishmania donovani trypanothione reductase (LdTryR)

Recombinant L. donovani trypanothione reductase (LdTryR)47 was kindly provided by Dr. Neena Goyal, The CSIR-Central Drug Research Institute, Lucknow, India. An enzyme inhibition assay was performed spectrophotometrically58. The enzyme inhibition kinetics were determined in an assay mixture (40 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA at pH 7.5) containing LdTryR and the substrate trypanothione disulphide T(S)2 (Sigma-Aldrich) at varying concentrations (25, 50, 100 and 200 µM), where β-sitosterolCCL as an inhibitor was added at concentrations of 0, 3.75, 7.5, and 15 µg/ml. The reactions were monitored by the addition of 100 µM NADPH (Sigma-Aldrich), and changes in absorbance were measured at 340 nm44. In the presence of β-sitosterolCCL, the mode of inhibition was detected by a Lineweaver–Burk plot, and the value of the inhibition constant (Ki) was calculated.

Molecular docking simulation

The three-dimensional coordinates of the atoms of the ligand β-sitosterol were obtained from Pubchem59. The amino acid sequence of the protein LdTryR from L. donovani was retrieved from UniProt with the accession number P39050. We used homology modelling to build the three-dimensional structure of LdTryR using 6I7N and chain B as templates. The stereo-chemical qualities of the modelled structure were validated through a Ramachandran plot by using the PROCHECK program. The structural qualities of the modelled protein were again analysed by Verify3D. A molecular docking study between the modelled structure of LdTryR and ligand (β-sitosterolCCL) was performed using the tool GOLD, and the best docking poses were chosen as per the GOLD scores60.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in the GraphPad Prism program (version 5.0 for Windows; Fay Avenue, La Jolla, CA, USA). The data are representative of three separate experiments and expressed as the mean ± standard error (S.E.)/standard deviation (S.D.) as stated in the figure legends. The significance of differences was calculated by using Student’s t-test (two-group comparison) and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison test (multiple-group comparison), where *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Department of Science and Technology (DST-SERB), Government of India [Grant Number: CRG/2018/000361]; the Indian Council of Medical Research, Government of India [Grant Number: Fellowship/21/2018-ECD-II]; and UGC-SAP (Phase-II) [Grant Number: F5-3/2018/DRS-II]. We thank Neena Goyal, Scientist, CSIR-Central Drug Research Institute, Lucknow, India, who provided recombinant Leishmania donovani trypanothione reductase (LdTryR). We also thank SAIF, AIIMS, New Delhi, India, for use of the TEM facility.

Author contributions

P.K.P. designed and conducted experimental work, data interpretation, and writing of the whole manuscript; S.C. guided the enzyme kinetics study and provided scientific suggestions. A.B. performed in silico modelling. T.C. supervised the entire research work and manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-77066-2.

References

- 1.Valdivia HO, et al. Comparative genomics of canine-isolated Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis from an endemic focus of visceral leishmaniasis in Governador Valadares, southeastern Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:40804. doi: 10.1038/srep40804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang WW, Matlashewski G. Loss of virulence in Leishmania donovani deficient in an amastigote-specific protein, A2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:8807–8811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burza S, Croft SL, Boelaert M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2018;392:951–970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31204-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alves F, et al. Recent development of visceral leishmaniasis treatments: successes, pitfalls, and perspectives. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018;31:e00048–e118. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00048-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atanasov AG, et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015;33:1582–1614. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pye CR, Bertin MJ, Lokey RS, Gerwick WH. Retrospective analysis of natural products provides insights for future discovery trends. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017;114:5601–5606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614680114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagle AS, et al. Recent developments in drug discovery for leishmaniasis and human African trypanosomiasis. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:11305–11347. doi: 10.1021/cr500365f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sen R, Chatterjee M. Plant derived therapeutics for the treatment of Leishmaniasis. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:1056–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pramanik PK, Paik D, Pramanik A, Chakraborti T. White jute (Corchorus capsularis L.) leaf extract has potent leishmanicidal activity against Leishmania donovani. Parasitol. Int. 2019;71:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2019.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plat J, et al. Plant-based sterols and stanols in health and disease: "consequences of human development in a plant-based environment?". Prog. Lipid Res. 2019;74:87–102. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bin Sayeed MS, Karim SMR, Sharmin T, Morshed MM. Critical analysis on characterization, systemic effect, and therapeutic potential of beta-sitosterol: a plant-derived orphan phytosterol. Medicines (Basel) 2016;3:29. doi: 10.3390/medicines3040029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Babu S, Jayaraman S. An update on β-sitosterol: a potential herbal nutraceutical for diabetic management. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020;131:110702. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, et al. β-sitosterol interacts with pneumolysin to prevent Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:17668. doi: 10.1038/srep17668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ododo MM, Choudhury MK, Dekebo AH. Structure elucidation of β-sitosterol with antibacterial activity from the root bark of Malva parviflora. Springerplus. 2016;5:1210. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2894-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panda SK, Luyten W. Antiparasitic activity in Asteraceae with special attention to ethnobotanical use by the tribes of Odisha, India. Activité antiparasitaire chez les Asteraceae avec une attention particulière pour l’utilisation ethnobotanique par les tribus d’Odisha en Inde. Parasite. 2018;25:10. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2018008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lagnika L, et al. Phytochemical study and antiprotozoal activity of compounds isolated from Thalia geniculata. Pharm. Biol. 2008;46:162–165. doi: 10.1080/13880200701499000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pulivarthi D, Steinberg KM, Monzote L, Piñón A, Setzer WN. Antileishmanial activity of compounds isolated from Sassafras albidum. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015;10:1229–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Majid Shah S, et al. β-Sitosterol from Ifloga spicata (Forssk.) Sch. Bip. as potential anti-leishmanial agent against leishmania tropica: docking and molecular insights. Steroids. 2019;148:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva AA, et al. Activity of cycloartane-type triterpenes and sterols isolated from Musa paradisiaca fruit peel against Leishmania infantum chagasi. Phytomedicine. 2014;21:1419–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodrigues RF, et al. Investigation of trypanothione reductase inhibitory activity by 1,3,4-thiadiazolium-2-aminide derivatives and molecular docking studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:1760–1766. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chauhan SS, et al. Novel β-carboline–quinazolinone hybrid as an inhibitor of Leishmania donovani trypanothione reductase: synthesis, molecular docking and bioevaluation. MedChemComm. 2015;6:351–356. doi: 10.1039/C4MD00298A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shadab M, et al. Apoptosis-like cell death in Leishmania donovani treated with KalsomeTM10, a new liposomal amphotericin B. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0171306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee N, et al. Programmed cell death in the unicellular protozoan parasite Leishmania. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:53–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kathuria M, et al. Induction of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in Leishmania donovani by orally active clerodane diterpene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014;58:5916–5928. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02459-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verçoza BRF, et al. KH-TFMDI, a novel sirtuin inhibitor, alters the cytoskeleton and mitochondrial metabolism promoting cell death in Leishmania amazonensis. Apoptosis. 2017;22:1169–1188. doi: 10.1007/s10495-017-1397-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perelman A, et al. JC-1: alternative excitation wavelengths facilitate mitochondrial membrane potential cytometry. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e430. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balasubramanian K, Mirnikjoo B, Schroit AJ. Regulated externalization of phosphatidylserine at the cell surface: implications for apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:18357–18364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brauchle E, Thude S, Brucker SY, Schenke-Layland K. Cell death stages in single apoptotic and necrotic cells monitored by Raman microspectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4698. doi: 10.1038/srep04698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Romero I, et al. Upregulation of cysteine synthase and cystathionine β-synthase contributes to Leishmania braziliensis survival under oxidative stress. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:4770–4781. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04880-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarkar A, et al. Flow cytometric determination of intracellular non-protein thiols in Leishmania promastigotes using 5-chloromethyl fluorescein diacetate. Exp. Parasitol. 2009;122:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corral MJ, et al. Allicin induces calcium and mitochondrial dysregulation causing necrotic death in Leishmania. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016;10:e0004525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbieri R, et al. Phytochemicals for human disease: an update on plant-derived compounds antibacterial activity. Microbiol. Res. 2017;196:44–68. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponte-Sucre A, et al. Drug resistance and treatment failure in leishmaniasis: A 21st century challenge. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11:e0006052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pramanik PK, Alam MN, RoyChowdhury D, Chakraborti T. Drug resistance in protozoan parasites: an incessant wrestle for survival. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019;18:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jgar.2019.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amin E, Moawad A, Hassan H. Biologically-guided isolation of leishmanicidal secondary metabolites from Euphorbia peplus L. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017;25:236–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kariyawasam UL, et al. Genetic diversity of Leishmania donovani that causes cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sri Lanka: a cross sectional study with regional comparisons. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017;17:791. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2883-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alcântara LM, et al. A multi-species phenotypic screening assay for leishmaniasis drug discovery shows that active compounds display a high degree of species-specificity. Molecules. 2020;25:2551. doi: 10.3390/molecules25112551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Escobar P, Matu S, Marques C, Croft SL. Sensitivities of Leishmania species to hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine), ET-18-OCH(3) (edelfosine) and amphotericin B. Acta Trop. 2002;81:151–157. doi: 10.1016/S0001-706X(01)00197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mandal G, et al. Species-specific antimonial sensitivity in Leishmania is driven by post-transcriptional regulation of AQP1. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015;9:e0003500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morais-Teixeira ED, Damasceno QS, Galuppo MK, Romanha AJ, Rabello A. The in vitro leishmanicidal activity of hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine) against four medically relevant Leishmania species of Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo. Cruz. 2011;106:475–478. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762011000400015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vallochi AL, et al. Lipid droplet, a key player in host-parasite interactions. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:1022. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boren J, Brindle KM. Apoptosis-induced mitochondrial dysfunction causes cytoplasmic lipid droplet formation. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1561–1570. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garcia FP, et al. A3K2A3-induced apoptotic cell death of Leishmania amazonensis occurs through caspase- and ATP-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction. Apoptosis. 2017;22:57–71. doi: 10.1007/s10495-016-1308-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ortalli M, et al. Identification of chalcone-based antileishmanial agents targeting trypanothione reductase. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;152:527–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson JL, et al. Improved tricyclic inhibitors of trypanothione reductase by screening and chemical synthesis. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:1333–1340. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ekins S, Mestres J, Testa B. In silico pharmacology for drug discovery: applications to targets and beyond. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007;152:21–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mittal MK, Misra S, Owais M, Goyal N. Expression, purification, and characterization of Leishmania donovani trypanothione reductase in Escherichia coli. Protein Express Purif. 2005;40:279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pramanik A, Paik D, Pramanik PK, Chakraborti T. Serine protease inhibitors rich Coccinia grandis (L.) Voigt leaf extract induces protective immune responses in murine visceral leishmaniasis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019;111:224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Galán LA, et al. Visible and near-infrared emission from lanthanoid β-triketonate assemblies incorporating cesium cations. Inorg. Chem. 2017;56:8975–8985. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mondal R, Mukherjee A, Biswas S, Kole RK. GC–MS/MS determination and ecological risk assessment of pesticides in aquatic system: a case study in Hooghly River basin in West Bengal, India. Chemosphere. 2018;206:217–230. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.04.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amaral M, et al. A semi-synthetic neolignan derivative from dihydrodieugenol B selectively affects the bioenergetic system of Leishmania infantum and inhibits cell division. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:6114. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42273-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tougan T, et al. Application of the automated haematology analyzer XN-30 in an experimental rodent model of malaria. Malar. J. 2018;17:165. doi: 10.1186/s12936-018-2313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lázaro-Souza M, et al. Leishmania infantum lipophosphoglycan-deficient mutants: a tool to study host cell-parasite interplay. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:626. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mukhopadhyay AG, Dey CS. Reactivation of flagellar motility in demembranated Leishmania reveals role of cAMP in flagellar wave reversal to ciliary waveform. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37308. doi: 10.1038/srep37308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Macedo T, Silva S, et al. In vitro antileishmanial activity of ravuconazole, a triazole antifungal drug, as a potential treatment for leishmaniasis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018;73:2360–2373. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mondal A, et al. Cytotoxic and inflammatory responses induced by outer membrane vesicle-associated biologically active proteases from vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 2016;84:1478–1490. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01365-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lima GS, Castro-Pinto DB, Machado GC, Maciel MA, Echevarria A. Antileishmanial activity and trypanothione reductase effects of terpenes from the Amazonian species Croton cajucara Benth (Euphorbiaceae) Phytomedicine. 2015;22:1133–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Colotti G, et al. Structure-guided approach to identify a novel class of anti-leishmaniasis diaryl sulfide compounds targeting the trypanothione metabolism. Amino Acids. 2020;52:247–259. doi: 10.1007/s00726-019-02731-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim S, et al. PubChem 2019 update: improved access to chemical data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:1102–1109. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones G, et al. Development and validation of a genetic algorithm for flexible docking. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;267:727–748. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.