Abstract

Objectives

Following the outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus and the subsequent global spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), health systems and the populations who use them have faced unprecedented challenges. We aimed to measure the impact of COVID-19 on the uptake of hospital-based care at a national level.

Design

The study period (weeks ending 5 January to 28 June 2020) encompassed the pandemic announcement by the World Health Organization and the initiation of the UK lockdown. We undertook an interrupted time-series analysis to evaluate the impact of these events on hospital services at a national level and across demographics, clinical specialties and National Health Service Health Boards.

Setting

Scotland, UK.

Participants

Patients receiving hospital care from National Health Service Scotland.

Main outcome measures

Accident and emergency (A&E) attendances, and emergency and planned hospital admissions measured using the relative change of weekly counts in 2020 to the averaged counts for equivalent weeks in 2018 and 2019.

Results

Before the pandemic announcement, the uptake of hospital care was largely consistent with historical levels. This was followed by sharp drops in all outcomes until UK lockdown, where activity began to steadily increase. This time-period saw an average reduction of −40.7% (95% confidence interval [CI]: −47.7 to −33.7) in A&E attendances, −25.8% (95% CI: −31.1 to −20.4) in emergency hospital admissions and −60.9% (95% CI: −66.1 to −55.7) in planned hospital admissions, in comparison to the 2018–2019 averages. All subgroup trends were broadly consistent within outcomes, but with notable variations across age groups, specialties and geography.

Conclusions

COVID-19 has had a profoundly disruptive impact on hospital-based care across National Health Service Scotland. This has likely led to an adverse effect on non-COVID-19-related illnesses, increasing the possibility of potentially avoidable morbidity and mortality. Further research is required to elucidate these impacts.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, A&E attendances, hospital admissions, uptake, secondary care

Introduction

Following the outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus and the subsequent global spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), unprecedented challenges have been placed on health systems and the populations who use them. The initial phase of the health system’s response was to ensure sufficient hospital capacity was available to deal with any surges in severe COVID-19 cases. This was accompanied by the need to minimise threats to the health of healthcare workers and the risk of transmission. This response has seen a major disruption to healthcare delivery and uptake across the world, including the UK and other parts of Europe.1–5 The extent of this disruption has not been fully quantified, particularly at a national level.

In Scotland, UK, the first positive case was announced on 1 March 20206 and, within the next fortnight, the number of confirmed cases surged to 210.7 In this period, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced COVID-19 as a pandemic on 11 March 20208 and Scotland confirmed its first death on 14 March 2020.9 Three days on, the Scottish Government announced that all non-urgent elective care was to be postponed.10 This was followed by the subsequent decision by the UK and Scottish Governments to institute a lockdown on 23 March 2020,11 where all Scottish residents were directed to self-isolate with non-essential services closing.12

To capture the impact of COVID-19 on the Scottish healthcare system, we sought to measure the influence of (1) the pandemic announcement by the WHO and (2) the UK/Scottish lockdown on accident and emergency (A&E) attendances, and emergency and planned hospital admissions across Scotland. To evaluate whether groups were impacted differently, we undertook additional analyses by patient demographics, clinical specialties and geography.

Methods

Study design and setting

We carried out a population-based interrupted time-series analysis in Scotland, using the 26 weeks from the weeks ending 5 January to 28 June 2020. Scotland is ideally suited to undertake this work given that most hospital care is free at the point of care and is predominately delivered by the National Health Service (NHS) Scotland. This public service is organised into 14 territorial NHS boards, seven special NHS Boards and one public health body. The latter is known as Public Health Scotland where most unified data on NHS Scotland are recorded.

Data sources

We obtained national data on A&E attendances and emergency and planned hospital admissions from the Public Health Scotland R Shiny App ‘COVID-19 wider impacts on the health care system’.13 This dashboard provides an overview of weekly changes in completed contacts with NHS Scotland’s clinical services during the pandemic. These data contained both COVID and non-COVID-related cases and was aggregated by patient demographics, hospital admissions clinical specialty and NHS Health Board. The underlying data sources of interest in this study are as follows.

A&E Data Mart

The A&E Data Mart captured A&E attendances14 from 105 emergency departments across Scotland.15 These were hospital departments that predominately provided consultant-led 24-h service care for emergency patients.16 This excluded all minor injury units, community A&E departments and small A&E sites, as they only submitted aggregate level data due to the lack of support to enable the collection of detailed patient-based information. These excluded small units and predominately covered more rural areas.15

The Rapid Preliminary In-patient Data Mart

We used the Rapid Preliminary In-patient Data (RAPID) Data Mart to capture acute care for in-patient admissions in all general hospitals across Scotland.17 This did not include maternity or neonatal care admissions and admissions to the Golden Jubilee National Hospital. This hospital is part of a special NHS Health Board ‘National Waiting Times Centre’ providing specialist and elective care for patients across Scotland.18 We anticipated no overall biases to the national picture from the exclusion of these data sources.

Variables

Exposures

To evaluate differing impacts across the uptake in healthcare services, data were aggregated by patient demographics, clinical specialties and the 14 territorial NHS Health Boards in Scotland.

Demographics included sex (female, male), age (under 5 years, 5–14 years, 15–44 years, 45–64 years, 65–74 years, 75–84 years, 85 years and over) and Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles (1–5). The Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation is a measure of deprivation unique to Scotland and is created by ranking small areas called data zones using seven domains of what makes an area ‘deprived’.19 These ranks were grouped into quintiles, where lower quintiles represented the most deprived areas and the higher quintiles representing the least.

Clinical specialties were defined as a specific area of clinical activity and were only applicable to emergency and planned hospital admissions. We used the following categories: A&E, Cancer, Cardiology, Community, Gynaecology, Medical (excluding Cardiology and Cancer), Paediatrics (medical), Paediatrics (surgical) and Surgery. A list of the specific specialties within these groups is given in the Public Health Scotland dashboard GitHub (https://github.com/Health-SocialCare-Scotland/covid-wider-impact).

The NHS Health Boards in Scotland were Ayrshire and Arran, Borders, Dumfries and Galloway, Fife, Forth Valley, Grampian, Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Highland, Lanarkshire, Lothian, Orkney, Shetland, Tayside and Western Isles.

Outcomes

We were interested in the impact on A&E attendances, and emergency and planned hospital admissions. An A&E attendance was defined as a record of whether a patient attended for the first time or a follow-up attendance to an NHS emergency department.16 An emergency hospital admission was defined as an unexpected admission following a visit to a doctor, an emergency ambulance call or A&E attendance.20 Planned (or elective) care was defined as an admission where the patient was given a date to attend the hospital for a planned procedure or treatment.20 These were measured using the relative change of weekly counts in 2020 to the averaged counts for equivalent weeks in 2018 and 2019. The weekly counts for these two years were combined because they were similar and to provide a more stable baseline for comparison.

Statistical methods

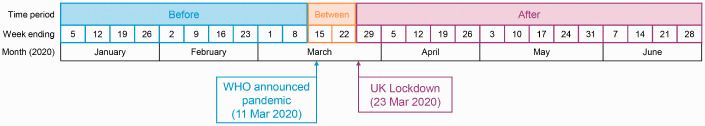

The interrupted time-series analysis used two change-points: 11 March 2020 (WHO announcing pandemic) and 23 March 2020 (UK lockdown). Three time-periods were therefore considered: before the pandemic announcement (weeks ending 5 January to 5 March 2020); between change-points (weeks ending 15 and 22 March); and after UK lockdown (weeks ending 29 March to 28 June 2020). A diagram of this timeline is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Timeline of time-periods and change-points. Before indicates weeks before pandemic announcement (weeks ending 5 January to 8 March 2020); Between indicates weeks between change-points (weeks ending 15 and 22 March 2020); After indicates weeks after UK lockdown (weeks ending 29 March to 28 June 2020).

The temporal trends of the outcomes were visualised using graphs of the percentage change from the weekly 2018–2019 average and the equivalent 2020 counts for all three outcomes by each of the exposures. We also reported on the overall mean percentage changes for the three outcomes across the three time-periods alongside their 95% confidence intervals.

We undertook an interrupted time-series analysis using segmented/piecewise linear regression21 to assess the overall impact of the change-points on the trends of the three outcomes of interest. This technique tested for different trend lines within the time-periods, which were visualised and reported using the estimated intercepts and slopes and their 95% confidence intervals. This meant there were only two observations for the time-period between the change-points (15–22 March), which gave rise to higher uncertainty around estimates fit in this time. These were still included for completeness but were not interpreted, with the main focus on the before and after time-periods.

We then took a comparative interrupted time-series analysis approach22 to test whether the levels within the exposures exhibited similar trend patterns in the weekly percentage changes within the time-periods. This was repeated for each of the three outcomes.

Time was captured using the number of days from 5 January (the first week in the analysis) as opposed to the date of the week. This allowed estimates to be more interpretable, particularly for the intercept which would estimate the average percentage change for the outcomes on 5 January 2020. Details on the specific modelling techniques used in the analyses can be found in S1 Appendix.

To protect patient confidentiality, the data supplied on specific groups were suppressed if a weekly count was below five, despite being included in the aggregate total for Scotland. Therefore, if a specific group had at least one suppressed value for a particular week, then the whole group was omitted when analysing the relevant subgroup trends. This only occurred in the planned hospital admissions for the specialty A&E and NHS Health Boards with small populations, including NHS Orkney, NHS Shetland and NHS Western Isles. NHS Forth Valley was also omitted for emergency and planned hospital admissions, due to a known data issue of the lowest completion rates in returning hospital-level data.23 We anticipated little bias in this as according to the National Records of Scotland’s 2019 mid-year estimates, NHS Forth Valley only contained 5% of the Scottish population.24

Reporting guideline

We used the Reporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected Data (RECORD) extended from the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement on reporting guidelines to support the communication of findings. This is found in S2 Appendix.

Ethics, software and dissemination

We obtained approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee, Southeast Scotland 02 under the Early Pandemic Evaluation and Enhanced Surveillance of COVID-19 (EAVE II) study. We used R/R Studio (R version 3.6.3) to carry out the analyses and to produce figures. All R code scripts will be made available on the EAVE II GitHub page (https://github.com/EAVE-II).

Results

A&E attendances, emergency and planned hospital admissions drop substantially during the pandemic across Scotland

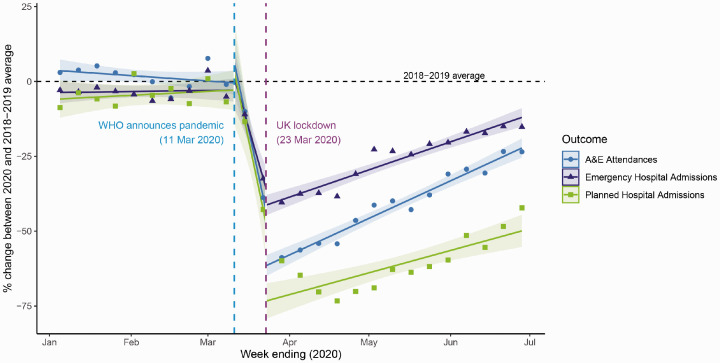

The fitted temporal trends of A&E attendances, emergency and planned hospital admissions before the WHO announcement were broadly consistent across the three outcomes and with the 2018–2019 baseline (Figure 2). This was followed by a sharp fall until the UK implemented lockdown following which there was a further decline; thereafter, trends have begun to return to the 2018–2019 average baseline (Figure 2). Emergency hospital admissions and A&E attendances appeared to be returning quicker than planned hospital admissions, which continued to fall further until the week ending 19 April 2020 (Figure 2). The overall mean percentage change to the 2018–2019 average after UK lockdown was −40.7% (95% confidence interval: −47.7 to −33.7) in A&E attendances, −25.8% (95% confidence interval: −31.1 to −20.4) in emergency hospital admissions and −60.9% (95% confidence interval: −66.1 to −55.7%) in planned hospital admissions. See S4 for temporal trends in the counts and S5 Appendix for further information.

Figure 2.

Fitted lines of segmented regression models for A&E attendances and emergency and planned hospital admissions across Scotland. Points represent weekly percentage changes between 2020 and 2018–2019 average weeks ending 5 January to 28 June 2020 for A&E attendances, emergency and planned hospital admissions. Vertical lines represent change-point 1 (WHO announcing pandemic on 11 March) and change-point 2 (UK lockdown on 23 March). Horizontal line is the 2018–2019 average at 0. Fitted lines represent segmented regression models of the interaction between the number of days since 5 January and the two change-points for each outcome. Shaded areas around lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

Age was the main demographic characteristic with differential impacts across services

Trends in all three categories of hospital use across sex, age and deprivation, displayed similar patterns to the Scotland level trends albeit with some variations (S3 Appendix, Figures 2 to 4). For sex, there was little variation between levels for trends which was confirmed when there was no important effect in the modelling.

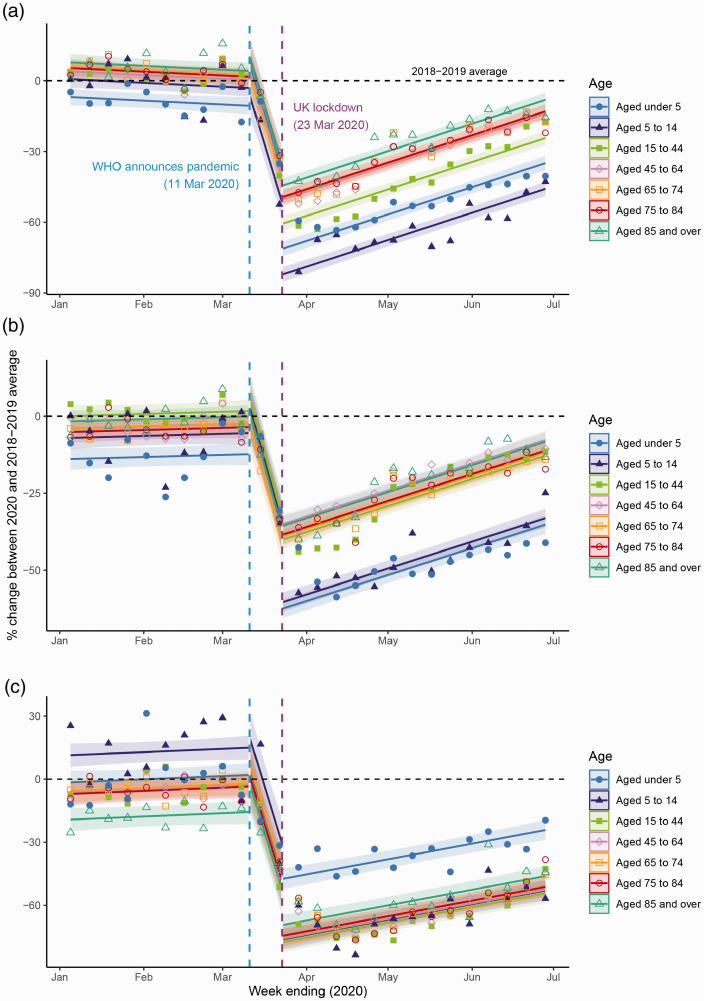

For age, there was an effect with the final chosen model capturing the same slope for each age group, which differed across the time-periods. These parallel trend lines changed in order depending on the time-period (Model 3, S1 Appendix). Plots of the fitted model suggested that younger age groups, particularly those under 15, were slower to recover for A&E attendances and emergency hospital admissions having gone down to much lower levels (Figure 3(a) and (b)). The youngest age group was the quickest to improve for planned hospital admissions (Figure 3(c)). See S6 Appendix for further information.

Figure 3.

Fitted lines of segmented regression models by age group for (a) A&E attendances, (b) emergency and (c) planned hospital admissions. Points represent weekly percentage changes between 2020 and 2018–2019 average weeks ending 5 January to 28 June 2020 by age group for (a) A&E attendances, (b) emergency and (c) planned hospital admissions. Vertical lines represent change-point 1 (WHO announcing pandemic on 11 March) and change-point 2 (UK lockdown on 23 March). Horizontal line is the 2018–2019 average at 0. Fitted lines represent segmented regression models of the baseline model (the number of days since 5 January and the two change-points) and the interaction between age and the change-points for each outcome. Shaded areas around lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

For deprivation, only emergency hospital admissions saw any substantial difference in the groups. This difference was only slight and it seemed to be driven by differences before the pandemic announcement. See S7 Appendix for further information.

Variations by clinical specialties were different among hospital admissions

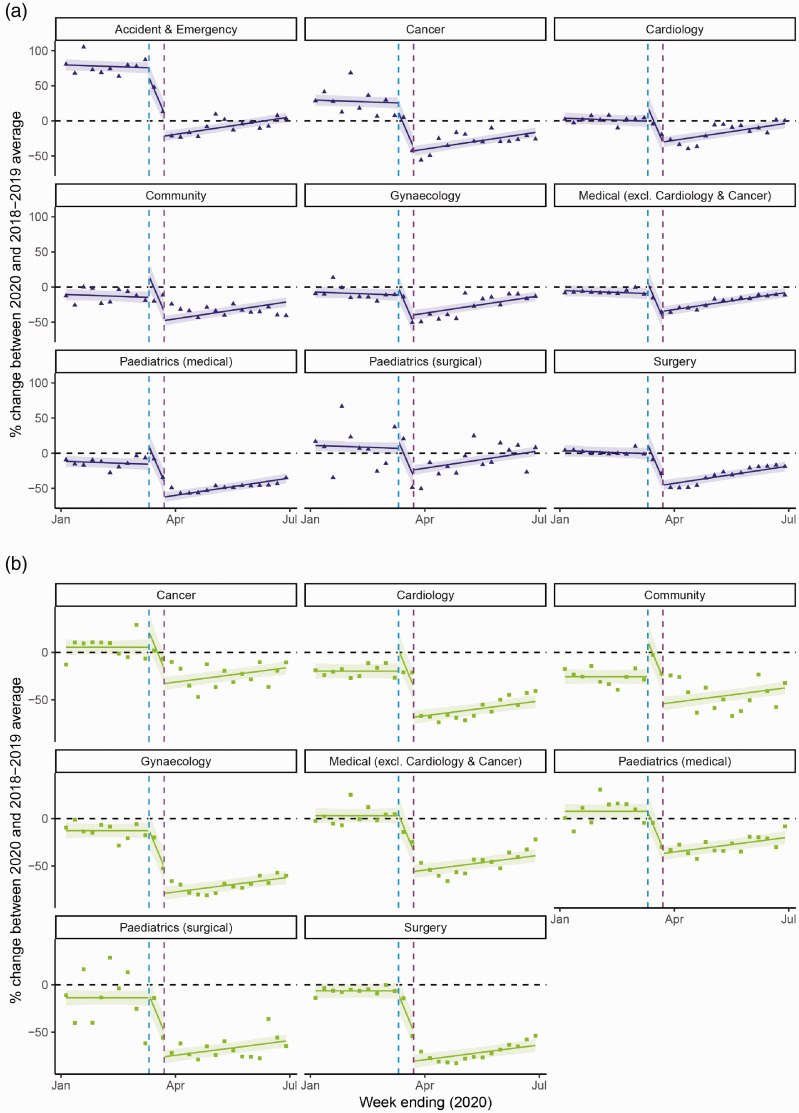

Investigating the differentiating impact of specialties for hospital admissions saw differing trends between emergency and planned admissions (S3 Appendix, Figure 5). There was a differing impact by speciality for both outcomes, with the final model having the same structure to the age models (Model 3, S1 Appendix).

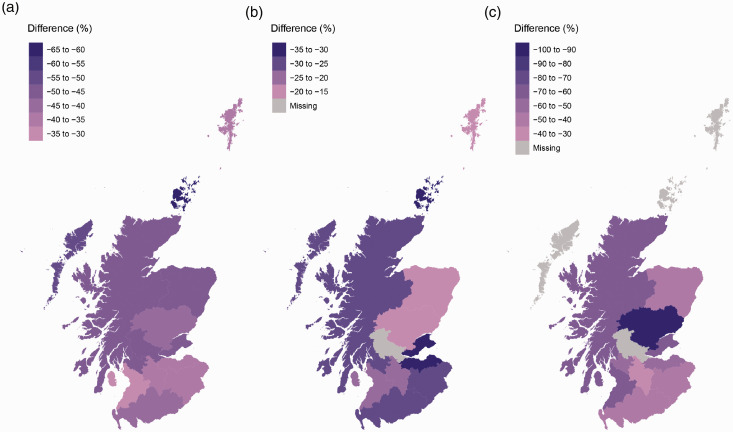

Figure 5.

Map of differences in mean percentage changes before pandemic announcement and after UK lockdown by NHS Scotland Health Board. The difference in the mean percentage changes before the pandemic announcement (weeks ending 5 January to 8 March 2020) and mean percentage changes after UK lockdown (weeks ending 29 March to 28 June 2020) for (a) A&E attendances, (b) emergency and (c) planned hospital admissions. Note: Orkney, Shetland and Western Isles excluded for planned hospital admissions due to small numbers. Forth Valley excluded for emergency and planned hospital admission due to data issues. Shapefile for map found on Scottish Government SpatialData.gov.scot (https://data.gov.uk/dataset/27d0fe5f-79bb-4116-aec9-a8e565ff756a/nhs-health-boards).

For emergency hospital admissions, higher rates before the WHO announcement in A&E and Cancer specialties had been captured. In terms of the trends back to the baseline after UK lockdown, most clinical specialties were very similar, with Paediatrics (medical) being notably lower (Figure 4(a)). There was also evidence of A&E, Cardiology and Gynaecology specialties returning to the 2018–2019 baseline averages by the end of the study (Figure 4(a)).

Figure 4.

Fitted lines of segmented regression models by specialty for (a) emergency and (b) planned hospital admissions. Points represent weekly percentage changes between 2020 and 2018–2019 average weeks ending 5 January to 28 June 2020 by specialty for (a) emergency and (b) planned hospital admissions. Vertical lines represent change-point 1 (WHO announcing pandemic on 11 March) and change-point 2 (UK lockdown on 23 March). Horizontal line is the 2018–2019 average at 0. Fitted lines represent segmented regression models of the baseline model (the number of days since 5 January and the two change-points) and the interaction between specialty and change-points for each outcome. Shaded areas around lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

For planned hospital admissions, there was a lot of variability due to small numbers, particularly for Community and Cancer (S4 Appendix, Figure 5(b)). Visualising the fitted lines showed that specialties before the first change-point were more similar than after the last change-point (Figure 4(b)). Specialties such as Cardiology, Gynaecology, Paediatrics (surgical) and Surgery remained at very low measurements and therefore little evidence of a quick return to the baseline (Figure 4(b)), whereas Cancer and Paediatrics (medical) were captured having quicker returns (Figure 4(b)). See S8 Appendix for further information.

NHS Health Boards were fairly consistent with the overall Scotland level trends

The percentage changes across NHS Health Boards for all outcomes were fairly similar to the overall Scotland changes (S3 Appendix, Figure 6). This was particularly evident in A&E attendances, where the map of the differences in the mean percentage changes before and after the change-points was mainly consistent (Figure 5(a)). Similarities between NHS Health Boards are shown for emergency hospital admission, where differences in the means spanned between a range of approximately 20% (∼−35% to ∼−15%) (Figure 5(b)). For planned hospital admissions, all areas displayed consistent differences geographically, except for NHS Tayside which had a much larger decrease (Figure 5(c)). This potential outlier can be explained by the unique temporal pattern of a consistent fall from the start of the study (S3 Appendix, Figure 6). See S9 Appendix for further information.

Discussion

Following the WHO announcement, there were overall sharp drops in A&E attendances, and emergency and planned hospital admissions and further drops until Scotland entered into lockdown. By the end of the study, these services were in the process of returning to historical levels, with some well below anticipated levels particularly elective care. These impacts were seen equally for both sexes and across deprivation quintiles. Age demonstrated some variation, with children aged under 15 years being particularly affected for emergency care (attendances and admissions). Across clinical specialties and NHS Health Boards, there were broadly consistent findings with the national data but with some notable variations.

Our data sources included almost all A&E and in-patient hospital care activity across Scotland. As far as we are aware, this analysis is the most inclusive investigation into the impact of COVID-19 on the uptake of hospital care on a national level. This in turn provides useful information for the NHS to plan for future services since, to an extent, results reflected the lack of pandemic preparedness in NHS Scotland.

Despite this, there are limitations to this study. First, there are gaps in the overall population, including minor injury units. Monthly attendances for minor injury units in Scotland exhibited similar patterns to the analyses, where attendances dropped in April 2020 and increased thereafter,25 further enhancing the results of our study. Second, the study may also have uncovered some data artefacts where there was a high spike in A&E specialties for emergency hospital admissions before the WHO announcement. This could be explained by the way hospitals organise and classify services, where those ‘held’ for a period of time in A&E generated an admission record. Alternatively, this could have been the result of a spike in influenza corresponding to this time.26 Using the Rapid Preliminary In-patient Data Mart to capture hospital admissions also has limitations. Rapid Preliminary In-patient Data records are provided quickly to Public Health Scotland so that the data can be used with minimum delay. This means that data have limited granularity – for example, there is no clinical coding of patient diagnoses or procedures. Alternative data sources should be sought out if this detailed information is required. Lastly, the aggregated structure of the data meant we were unable to adjust for confounding by the demographic variables. Although we note that substantial changes in the population structure of Scotland over the observed time-period are an extremely unlikely explanation for our findings.

Similar findings have been observed in other parts of the UK and Europe, albeit studying a more limited set of outcomes or focusing on sub-samples of the population. In England, The Health Foundation showed that the average number of daily A&E visits and emergency admissions dropped from February to April 2020.1 This drop was also noted in NHS England’s statistical commentary for emergency care in March 2020.2 In France, the number of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest hospital admissions substantially reduced, which has led to a major rise in deaths related to out-of-hospital cardiac arrests.3 In Italy, the overall number of urgent surgical procedures performed in a sample of surgical centres dropped substantially from February to March 2020 in comparison to 2019.4 In Austria, the number of hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome in a sample of public primary percutaneous coronary centres had significantly declined throughout the pandemic.5

We believe the drop between the pandemic announcement and lockdown is therefore a true effect. For elective care, the slow recovery reflected changes to service provision implemented as part of pandemic preparedness planning, where all non-urgent elective care was postponed in Scotland from 17 March.10 This excluded all vital cancer treatments, emergency, maternity and urgent care,10 which were captured in our data except maternity care. For emergency care, changes to population health-seeking behaviour from fear of contracting the virus or overwhelming the NHS could have played a role in this decline. Additionally, the non-essential movement constraints and physical distancing introduced during lockdown12 may have also contributed to this. Google mobility data for this time-period showed an overall reduction of 63% in movement,27 suggesting reduced risks of accidents and other infections. The lack of public awareness that medical help should be sought in an emergency could also help drive this, particularly during the early stages of the pandemic. With an increase in serious complications in-patients who were avoiding or delaying medical help, the Government launched a campaign to reassure the public that NHS services remained ‘open for business’,28 which could reflect the increasing activity.

The disruptive impact in emergency care for those under 15, which is also correlated with Paediatric care, could be explained by a few potential reasons. Social distancing in children could have reduced the risk of non-COVID-19 infections and injuries, which are the most common reasons for emergency admissions in children.29 Other more speculative reasons could be the change in behaviour from parents, who may have avoided attending medical facilities to protect their children from the virus, or possible alternative routes set up by hospitals to avoid Paediatric admissions.

To give further explanation to our findings in emergency care, we compared results to COVID-19-related hospitalisations. Information on the number of A&E attendances for COVID-19 in Scotland is currently unavailable due to variable quality of diagnostic coding on A&E records and we would not expect COVID-19 to have contributed to elective care. Data on COVID-19 hospitalisations are supplied by Public Health Scotland’s weekly statistical reports and were defined as patients who tested positive 14 days prior to admission to hospital, on the day of their admission or during their stay in hospital.30 The number of COVID-19 admissions gradually rose from early March, peaked in April and steadily decreased thereafter. During the peak week (ending 5 April) 1272 COVID-19 admissions were recorded,30 comprising 17% of all emergency hospital admissions in that week (7521).13 This illustrates the extent of COVID-19’s contribution on emergency care seen in the period immediately following the UK lockdown. Over time, the COVID-19 activity has fallen and remained low, while non-COVID-19 conditions will have contributed proportionally more.

Future analyses should focus on all aspects of the patient journey from GP consultations, out-of-hours care, community care and the use of specialised care such as mental health services. Given that the overall trends for neither A&E nor in-patient care had returned to baseline levels by the end of the study, there is a need to continue monitoring these trends. This includes the long-term impacts on potentially avoidable morbidity and mortality across Scotland.

Conclusions

COVID-19 has led to profound drops in A&E attendances, and emergency and planned hospital admissions across Scotland during the first few months of the pandemic. Our findings also raise important questions about the resilience of hospital services in NHS Scotland. There is now a need to investigate the impact of this disruption on preventable morbidity and mortality.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrs-10.1177_0141076820962447 for Impact of COVID-19 on accident and emergency attendances and emergency and planned hospital admissions in Scotland: an interrupted time-series analysis by Rachel H Mulholland, Rachael Wood, Helen R Stagg, Colin Fischbacher, Jaime Villacampa, Colin R Simpson, Eleftheria Vasileiou, Colin McCowan, Sarah J Stock, Annemarie B Docherty, Lewis D Ritchie, Utkarsh Agrawal, Chris Robertson, Josephine LK Murray, Fiona MacKenzie and Aziz Sheikh in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine

Acknowledgements: We are grateful for the Public Health Scotland team who have created and monitor the dashboard for the underlying data. These include Victoria Elliott, Ewout Jaspers and Diane Gibbs. Many thanks to Helen Stagg and Chris Robertson for their advice on the methods.

Dissemination: All R code scripts on the analysis and figures will be made available on the EAVE II GitHub page (https://github.com/EAVE-II).

Provenance: Not commissioned; peer-reviewed by Ansu Basu, Michael Bath and Julie Morris.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Declarations

Competing Interests: AS is a member of the Editorial Board of the Journal of Royal Society of Medicine and a member of the Scottish Government’s COVID-19 Chief Medical Officer’s Advisory Group. CRS reports grants from the UK National Institute for Health Research, Medical Research Council and New Zealand Health Research Council, and The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment during the conduct of (and related to) the study. Remaining authors do not declare competing interests.

Funding: This analysis is part of the Early Pandemic Evaluation and Enhanced Surveillance of COVID-19 (EAVE II) study. EAVE II is funded by the Medical Research Council (MR/R008345/1) with the support of BREATHE – The Health Data Research Hub for Respiratory Health (MC_PC_19004), which is funded through the UK Research and Innovation Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund and delivered through Health Data Research UK. Additional support has been provided through the Scottish Government DG Health and Social Care. HRS is supported by the Medical Research Council (MR/R008345/1).

Ethical approval: We obtained approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee, Southeast Scotland 02 under the EAVE II study.

Guarantor: RHM.

Contributorship: AS and RW conceived this manuscript. RW, CF, JV and FM helped create the PHS dashboard used as the data source. RHM led the analysis and writing up of this manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

ORCID iDs

Rachel H Mulholland https://orcid.org/000-0003-1020-3373

Rachael Wood https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4453-623X

Annemarie B Docherty https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8277-420X

References

- 1.Kelly E and Firth Z. The Health Foundation. How Is COVID-19 Changing the Use of Emergency Care? 15 May 2020. See https://www.health.org.uk/news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/how-is-covid-19-changing-the-use-of-emergency-care (last checked 30 June 2020).

- 2.NHS England. A&E Attendances and Emergency Admissions. March 2020 Statistical Commentary. See https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/04/Statistical-commentary-March-2020-jf8hj.pdf (last checked 10 July 2020).

- 3.Marijon E, Karam N, Jost D, Perrot D, Frattini B, Derkenne C, et al. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic in Paris, France: a population-based, observational study. Lancet Public Health 2020. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30117-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Patriti A, Baiocchi GL, Catena F, Marini P, Catarci M. FACS on behalf of the Associazione Chirurghi Ospedalieri Italiani (ACOI). Emergency general surgery in Italy during the COVID-19 outbreak: first survey from the real life. World J Emerg Surg 2020; 15: article number 36–article number 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metzler B, Siostrzonek P, Binder RK, Bauer A, Reinstadler SJ. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J 2020; 41: 19–19. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scottish Government. News, Coronavirus (COVID-19) confirmed in Scotland. 1 March 2020. See https://www.gov.scot/news/coronavirus-covid-19/ (last checked 30 June 2020).

- 7.Health Protection Scotland and Public Health Scotland. Total Scotland COVID-19 Cases Dashboard. See https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/658feae0ab1d432f9fdb53aa082e4130 (last checked 30 June 2020).

- 8.World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19. 11 March 2020. See https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020 (last checked 26 June 2020).

- 9.Scottish Government. News, First Death of Patient From Coronavirus (COVID-19). 13 March 2020. See https://www.gov.scot/news/first-death-of-patient-from-coronavirus-covid-19/ (last checked 30 June 2020).

- 10.Scottish Government. News, NHS Scotland Placed on Emergency Footing. 17 March 2020. See https://www.gov.scot/news/nhs-scotland-placed-on-emergency-footing/ (last checked 30 June 2020).

- 11.GOV.UK. Coronavirus (COVID-19). Guidance and Support. PM Address to the Nation on Coronavirus: 23 March 2020. See https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-23-march-2020 (last checked 26 June 2020).

- 12.Scottish Government. News, Social Distancing Enforcement Measures in Place. 27 March 2020. See https://www.gov.scot/news/social-distancing-enforcement-measures-in-place/ (last checked 30 June 2020).

- 13.Public Health Scotland. COVID-19 Wider Impacts on Health Care System. See https://scotland.shinyapps.io/phs-covid-wider-impact/_w_c89e0e10/#tab-5169-2 (last checked 09 July 2020).

- 14.Public Health Scotland. Accident and Emergency Data Mart. See https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Emergency-Care/Accident-and-Emergency-Data-Mart/#:∼:text=The%20A%26E%20data%20mart%20gives,or%20elsewhere%20in%20NHS%20Scotland (last checked 26 June 2020).

- 15.Public Health Scotland. Emergency Care. NHS Scotland Accident & Emergency Sites. See https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Emergency-Care/Emergency-Department-Activity/Hospital-Site-List/ (last checked 10 July 2020).

- 16.Public Health Scotland. Emergency Department Statistics Background Information and Glossary. See https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Emergency-Care/ED_Background_Glossary.pdf (last checked 10 July 2020).

- 17.ISD Scotland. National Data Catalogue. Rapid Preliminary In-patient Data (RAPID). See https://www.ndc.scot.nhs.uk/National-Datasets/data.asp?SubID=37 (last checked 26 June 2020).

- 18.NHS Golden Jubilee. Home. See https://hospital.nhsgoldenjubilee.co.uk/ (last checked 10 July 2020).

- 19.Scottish Government. Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2020. See https://www.gov.scot/collections/scottish-index-of-multiple-deprivation-2020/ (last checked 26 June 2020).

- 20.Public Health Scotland. Acute Hospital Activity & NHS Beds Information. See https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Hospital-Care/Publications/2019-05-28/Acute-Hospital-Publication/glossary/ (last checked 10 July 2020).

- 21.Bernal JB, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol 2017; 46: 348–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linden A. Conducting interrupted time-series analysis for single- and multiple-group comparisons. Stata J 2015; 15: 480–500. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Public Health Scotland. Data Support and Monitoring. SMR Completeness. See https://www.isdscotland.org/products-and-Services/Data-Support-and-Monitoring/SMR-Completeness/ (last checked 10 July 2020).

- 24.National Records of Scotland. Mid-2019 Population Estimates Scotland. 2020. See https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/population/population-estimates/mid-year-population-estimates/mid-2019 (last checked 15 July 2020).

- 25.Public Health Scotland. A&E Activity and Waiting Times. 4 August 2020. See https://beta.isdscotland.org/find-publications-and-data/health-services/hospital-care/ae-activity-and-waiting-times/ (last checked 21 August 2020).

- 26.Public Health England. PHE Weekly National Influenza Report. 2020. See https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/863975/Weekly_national_influenza_report_week_6_2020.pdf (last checked 15 July 2020).

- 27.Drake TM, Docherty AB, Weiser TG, Yule S, Sheikh A and Harrison EW. The effects of physical distancing on population mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Lancet Digital Health 2020. DOI: 10.1016%2FS2589-7500(20)30134-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Public Health England. NHS ‘Open for Business’ Campaign Materials. See https://coronavirusresources.phe.gov.uk/nhs-resources-facilities/resources/open-for-business/ (last checked 15 July 2020).

- 29.Public Health Scotland. Diagnoses. Hospital Care. See https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Hospital-Care/Diagnoses/ (last checked 16 September 2020).

- 30.Public Health Scotland. COVID-19 Statistical Report. 2 September 2020. See https://beta.isdscotland.org/find-publications-and-data/population-health/covid-19/covid-19-statistical-report/ (last checked 16 September 2020).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jrs-10.1177_0141076820962447 for Impact of COVID-19 on accident and emergency attendances and emergency and planned hospital admissions in Scotland: an interrupted time-series analysis by Rachel H Mulholland, Rachael Wood, Helen R Stagg, Colin Fischbacher, Jaime Villacampa, Colin R Simpson, Eleftheria Vasileiou, Colin McCowan, Sarah J Stock, Annemarie B Docherty, Lewis D Ritchie, Utkarsh Agrawal, Chris Robertson, Josephine LK Murray, Fiona MacKenzie and Aziz Sheikh in Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine