Abstract

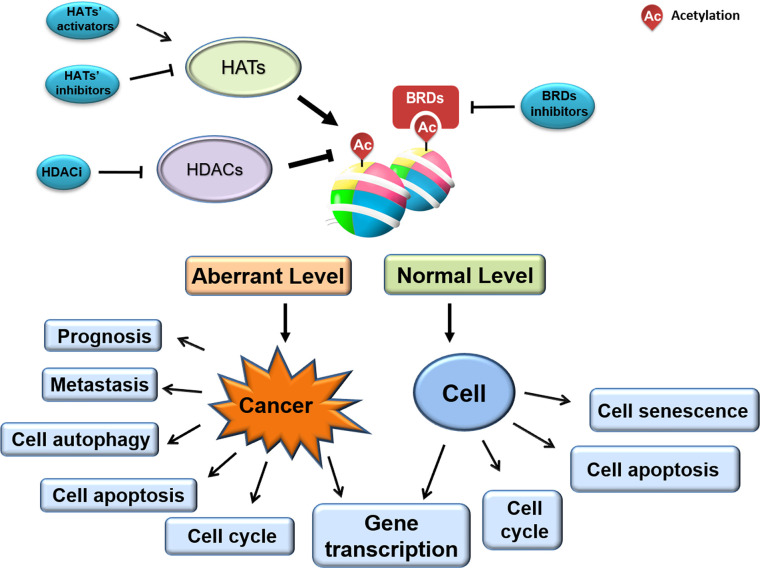

Evidence for research over the past decade shows that epigenetic regulation mechanisms run through the development and prognosis of tumors. Therefore, small molecular compounds targeting epigenetic regulation have become a research hotspot in the development of cancer therapeutic drugs. According to the obvious abnormality of histone acetylation when tumors occur, it suggests that histone acetylation modification plays an important role in the process of tumorigenesis. Currently, as a new potential anti-cancer therapeutic drugs, many active small molecules that target histone acetylation regulatory enzymes or proteins such as histone deacetylases (HDACs), histone acetyltransferase (HATs) and bromodomains (BRDs) have been developed to restore abnormal histone acetylation levels to normal. In this review, we will focus on summarizing the changes of histone acetylation levels during tumorigenesis, as well as the possible pharmacological mechanisms of small molecules that target histone acetylation in cancer treatment.

Keywords: histone acetylation, cancer, histone deacetylase, histone deacetylase inhibitor, histone acetyltransferase

Introduction

Histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) directly impact gene transcription by regulating the chromatin architecture (1). Histone acetylation is one of the most well-studied and important PTMs, which mainly affects the status of local chromatin relaxation through changing the distribution of histone acetylation marks in the local chromatin region, thereby regulating gene transcription activation (2). In more detail, the acetylation of histones occurs in the lysine residues on the N-terminal tail of the nucleosome histones composed of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, and the histone deacetylases (HDACs) and the histone acetyltransferases (HATs) are responsible for adding or removing acetyl groups from the N-terminal tail of the nucleosome histones (3). A large amount of research data demonstrated that histone acetylation widespread in cells is involved in various cellular activities, including genome maintenance, biological processes, DNA damage repair, cell cycle, and apoptosis (4). Once the dynamic balance between acetylation/deacetylation in cells is disrupted, it will cause various diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, leukemia, and even cancer (5–7). The following will specifically explain the changes in histone acetylation levels during cancer development, and how small molecules as cancer therapeutic drugs target and regulate intracellular acetylation levels.

Imbalanced Histone Acetylation Levels in Tumorigenesis

Based on the role of histone acetylation in the activation of gene expression, researchers speculated the mechanisms by which histone acetylation participated in and regulated progression of tumorigenesis (8). Multiple histone N-terminal acetylation sites have been identified ( Figure 1 ). And many lysine sites on histones are obviously abnormally modified by acetylation in cancer cells and tumor tissues, suggesting that changes in their acetylation levels are closely related to the occurrence of cancer. Consistent with this argument, it has been confirmed that some HATs or HDACs are abnormally expressed when cancer occurs, resulting in alteration of local chromatin structure by changing the distribution of histone acetylation, ultimately affecting the expression of genes related to tumorigenesis.

Figure 1.

Aberrant acetylation on histone N-terminal sites in certain cancer. K, Lysine.

It has been reported that the level of acetyl-modification on some histone lysine sites in cancer cells or tissues is obviously abnormal, and the increase or decrease of the modification level varies according to the type of cancer. Regarding H2A, Hat1 knockdown- or Tip60 abrogation-mediated downregulation of HeLa cell H2A lysine 5 acetylation (H2AK5ac) decreases HeLa cell colony size, suggesting that this acetylation can regulate cell proliferation (9). Furthermore, Ras-ERK1/2 pathway activation-induced osteosarcoma proliferation and migration co-occurs with downregulated H2BK12ac, a phenotype rescued by HDAC1 knockdown-mediated H2BK12ac restoration (10). Relative to other types of histone acetylation, the H2BK20ac modification preferentially accumulates at promoters of cell type-specific genes, indicating a role in regulating cell-specific functions (11).

Previous data indicate that the acetylation of specific histone lysine sites is associated with the occurrence of certain cancers. Recent research reported that histone H3 acetylation level is correlated with the pathological stage of colorectal cancer, especially with the depth of tumor invasion (12). For instance, downregulation of H3K4ac and H3K9ac has been observed in oral squamous cell carcinoma and ovarian tumors, and the status of acetylation level is tightly correlated with tumor stage, perineural invasion and tumor prognosis (13–15). Part of the reason for the above results may be related to its distribution region on chromatin. Because subsequent studies found that H3K4ac is enriched in the promoter regions of genes which associated with cancer-related phenotypic features, such as the estrogen response and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway (16, 17). In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cells, H3K4ac modulated by HDAC3 is enriched around the transcription start site of EMT related genes such like GLI1 and SMO, co-overexpression of which promotes HNSCC cell invasion and migration ability (18). In addition to H3K4ac and H3K9ac, high-level of H3K23ac, which is correlated with TRIM24, has been observed in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer, and this correlates with a shorter survival interval (19). Moreover, H3K27 represents a site vulnerable to multiple modification types, including methylation and acetylation, and upregulated H3K27ac in colon cancer and glioma cells is correlated with tumor invasive capability (20, 21). In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), H3K27ac activates long non coding RNA colon cancer associated transcript-1 (CCAT1), thereby promotes ESCC cells proliferation and migration (22). It is worth noting that some lysine-sites acetylation on histone H3 have been used as biomarkers. For example, H3K18ac and H3K4me2 has been used as biomarker in prostate, pancreatic, lung, and kidney cancers (23, 24). Taken together, unbalanced acetylation level of histone H3 in various cancer tissues or cells suggests that H3 acetylation may be involved in the transcriptional regulation of cancer-related genes.

Regarding H4, modifiable residue K16 is well-studied, and H4K16ac is frequently downregulated in breast cancer, medulloblastoma (25, 26), renal cell carcinoma (RCC), colorectal cancer (CRC) (27, 28), and ovarian cancer (29, 30). However non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) exhibits upregulation of H4K16ac and HAT hMOF, resulting in downstream gene expression alterations correlating with tumor size, cell proliferation, and migration (31, 32). In particularly, in NSCLC cells hMOF promotes S phase entry by regulating Skp2, thereby stimulates NSCLC tumorigenesis (31). On the other hand, downregulation of H4K5ac observed in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is associated with shorter survival intervals, and suppressed H4K5ac by MYST2 (Moz-Ybf2/Sas3-Sas2-Tip60) inhibition promotes AML cell growth and colony formation (33). In addition, downregulated H4K12ac consistent with HDAC1, HDAC2, and HDAC6 have been demonstrated in situ in invasive ductal carcinoma (34). Whereas upregulated H3K18ac and H4K12ac are observed in pancreatic cancer (24). A unique role for H4K20ac enriched at transcriptional start sites, co-localizing with NRSF/REST to participate in gene repression has been noted in cancer cells (35).

In summary, biological mechanisms employing acetylated histones are much more diverse than chromatin structure regulation alone. The numerous N-terminal tail lysine residue acetylation sites of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 allow them to participate in various signaling pathways, and facilitate their multi-faceted roles in cancer cell biology. Indeed, various cancers exhibit a globally dysregulated histone acetylation pattern, correlating with progression, pathological stage, and prognosis. As such, acetylation patterns may have potential as valuable prognostic markers (24).

HATs, HDACs and BRDs Act as “Writers”, “Erasers,” and “Readers” Respectively

Biological mechanisms employing acetylated histones are much more diverse than chromatin structure regulation alone. The numerous N-terminal tail lysine residue acetylation sites of H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 allow them to participate in various signaling pathways, and facilitate their multi-faceted roles in cancer cell biology. As mentioned, various cancers exhibit a globally dysregulated histone acetylation pattern, correlating with progression, pathological stage, and prognosis. As such, acetylation patterns may have potential as valuable prognostic markers (24). Noting that the dynamic change and reversible process of the acetyl-group at the N-terminal lysine site of histones can be controlled by certain proteins just like writers, erasers and readers. Cancer-associated abnormal histone acetylation profiles are due to corresponding aberrant expression or catalytic activities of these enzymes. HATs function as “writers”, transferring the acetyl group (-COCH3) from acetyl-CoA (Ac-CoA) to a target histone, whereas HDACs function as “erasers”, removing the acetyl group of a target histone (36, 37). However, whether it is to remove the acetyl group or recruit proteins to a specific acetyl-modified lysine site, the proteins usually have to recognize the acetyl group on a specific protein just like a reader.

Histone-mark readers often recognize marks through the functional domain contained in itself. Based on published literatures, the readers that can recognize histone acetylation are roughly divided into three categories including bromodomain-containing protein (BRD), PHD finger and YEATS domains. Among them, PHD finger and YEATS domain proteins have a wide range of functions. In addition to acetyl-group, they can also recognize methyl-group or other proteins. For example, PHD finger proteins can able to acquaint acetylated or unacetylated and methylated histones. However, BRD is the only protein group featuring a domain that is able to recognize and bind acetylated histone lysine residues. BRD-containing proteins are widely present in most tissues. According to the sequence or structure similarity, BRDs are divided into eight families exhibiting various activities, including histone modification and chromatin remodeling ( Figure 2 ) (38, 39). For example, one of the most well-known BRD family members, BRD4, accumulates in highly acetylated and transcriptionally prone chromatin regions (including promoters and enhancers) and promotes RNA polymerase II (RNA Pol II) activity, thereby stimulating transcription initiation and transcript elongation. BRD4 is involved in HCC cell growth and invasiveness in vitro, and it is significantly upregulated in HCC tissue (a feature also associated with HCC progression) (40). Such functions are largely dependent on the ability of BRD4 to recognize acetylated proteins (41).

Figure 2.

Histone acetylation “writers”, “erasers” and “readers”. ASH1L,ash1 (absent, small, or homeotic)-like; ATAD2, Two AAA domain containing protein; ATAD2B, KIAA1240 protein; BAZ, Bromodomain adjacent to zinc finger domain; BPTF, Fetal Alzheimer antigen; BRD, Bromodomain-containing protein; BRDT, Bromodomain-containing protein, testis specific; BRPF1, Bromodomain- and PHD finger-containing protein; BRWD3, Bromodomain-containing protein disrupted in leukemia; CBP, CREB-binding protein; CECR2, Cat eye syndrome chromosome region, candidate 2; CREBBP, CREB Binding Protein; EP300, E1A-binding protein p300; GCN5L2, General control of amino acid synthesis 5-like 2; GNAT, GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase; HAT, histone acetyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylases; MLL, Myeloid/lymphoid or mixed lineage leukemia; MYST, Moz-Ybf2/Sas3-Sas2-Tip60; ORPHAN, Orphan-containing family P300, E1A binding protein p300; PBRM1,Polybromo 1; PCAF, P300/CBP-associated factor; PHIP, Pleckstrin homology domain-interacting protein; SIRT, sirtuin; SMARCA, SWI/SNF-related matrix associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin a; SP100, Nuclear antigen Sp100; SP110, Nuclear antigen Sp110 A; SP140, SP140 nuclear body protein; SP140L, SP140 nuclear body protein like; TAF1,TAF1 RNA polymerase II, TATA box-binding protein (TBP)-associated factor; TAF1L, TAF1-like RNA polymerase II, TATA box-binding protein (TBP)-associated factor; TIP60, Tat interactive protein 60-kDa; TRIM24, Tripartite motif-containing 24; WDR9, WD repeat domain 9; ZMYND8, Zinc Finger MYND-Type Containing 8; ZMYND11, remodeling factor containing 11.

Considering the above description, the addition, removal and recognition of acetyl groups on histones is an indispensable dynamic balance. In other words, acetylation profiles regulated by HATs, HDACs, and BRDs, ultimately impact an abundance of target genes involved in tumorigenesis, thus regulating numerous cellular processes. For example, downregulation of TIP60 in 61% of primary gastric cancer patients is correlated with invasiveness and metastasis (42). Later research data supports this result. Currently, it is generally believed that alteration of HATs or HDACs level is involved in the occurrence and progression of cancer. From the published literature, the decrease of HATs and its enzymatic activity or the excessively high activity of HDACs can directly or indirectly affect the global acetylation level in cells. HAT MOF expression is downregulated in numerous cancers, including RCC, ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, and CRC (33). For additional detail, accumulating data reveals mutation residues on HATs in certain cancer, such as TIP60 in CRC (8). On the contrary, higher level of HDACs such as SIRT1, SIRT2, and SIRT7 were detected in cancer cells (43–45). Given this close relationship, an increasing number of small molecules targeting histone acetylation-regulating proteins are being investigated for their anti-cancer therapeutic potential.

Small Molecules Targeting HATs, HDACS, and BRDs in Cancer Therapy

HDAC Inhibitors (HDACis)

HDACs are enzymes that remove acetyl group on Lys residues of histone proteins, the following four classes of HDACs are recognized: I (HDAC1, 2, 3, and 8), II (A: HDAC4, 5, 7, and 9; B: HDAC6 and 10), III (SIRT1-7), and IV (HDAC11) ( Figure 2 ) (46). Given that the HDACs frequently show higher expression levels in cancer cells, small molecules targeting HADCs were first investigated. At present, many small molecules have been developed as HDAC inhibitors (HDACis). These HDACis may target different stages of cancer or different signaling pathways, and ultimately achieve the purpose of inhibiting or treating cancer.

So far, five HDACis Vorinostat (SAHA), Belinostat (PXD-101), Panobinostat (LBH589), and chidamide (CS055, HBI-8000) and Romidepsin (FK228) have been approved by the U.S. FDA (Food and Drug Administration) as medicines for treatment of skin T-cell lymphoma (TCL) and peripheral TCL (47, 48). The former three HDACis inhibit class I, II, and IV HDACs, while Romidepsin selectively targets class I (47). As one of the best-studied and pan-HDACi SAHA induces autophagy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, breast cancer as well as colon cancer cell lines, and the induced autophagy modulates mutant p53 degradation, further affects cancer cell survival (49, 50). In addition to use alone, SAHA induces radio treatment pancreatic cancer cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by targeting RAD51, clarifying the function of SAHA in enhance radiosensitivity (51). In combination with other anti-cancer drugs, such as oxaliplatin (Eloxatin) and ruxolitiniband, SAHA optimally inhibits cancer cell proliferation (52, 53). In addition, an isotretinoin-SAHA combination for the treatment of neuroblastoma is currently undergoing phase I clinical trials (54).

In addition to SAHA, there are already more than 20 kinds of HDACis are in different stages of clinical research, indicating that the research and development of HDACis is very popular and has broad development prospects. Most of the HDACis studied extensively are aimed at the proliferation of tumor cells by targeting cell cycle and apoptosis, growth, and migration capability (55). CG200745, is a pan HDACi, targets HDACs and modulates acetylation, thereby regulates down-stream genes including p53, myeloid cell leukemia-1 (Mcl-1) and B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-xL) (56, 57). In detail, CG200745 inhibits NSCLC cell growth by modulating the profile of H4K16ac at the transcription start site of cell proliferation related genes (58). Moreover, CG200745 (59, 60) enhances the expression of p53 target genes by regulating p53 acetylation, thereby inducing clonogenic cell death (56). (61) In pancreatic cancer, CG200745 elevates the H3 acetylation level and induces the expression of apoptotic proteins, furthermore, CG200745 works better in combination with gemcitabine or erlotinib in suppressing cancer cell proliferation (62). The ability of CG200745 to sensitize tumor cells to existing chemotherapeutic drugs (such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), cisplatin, and oxaliplatin) has also been demonstrated (57, 62–64). These data recommend the pan-HDACi CG200745 as a candidate anti-tumor drug or chemotherapy adjuvant, and is currently undergoing the phase I/II clinical trials for pancreatic cancer (62, 65–67).

Although the aforementioned pan-HDACis were approved for clinical application, side effects of these drugs like fatigue, nausea, thrombocytopenia, and cardiotoxicity limit its application (67). Thus, selective HDACis that target HDAC6, SIRT1 and SIRT2 have also appeared in recent years. For example, at least six HDAC6-selective inhibitors including SKLB-23bb, ACY1215 (rocilinostat), ACY241, Tubacin, Tubastatin A, and C1A have been reported (68). In several types of cancer cells such as bladder cancer, malignant melanoma and glioblastoma, HDAC6 is frequently over-expressed (69–71). As a mysterious of HDAC family, HDAC6 possess two catalytic domains and a ubiquitin-binding domain (BUZ), and selective-HDAC6 inhibitors are designed to block the effects of those special functional domains. Selective HDAC6 inhibitors Tubacin and tubastatin A are first developed because they can inhibit the proliferation of glioma and NSCLC by inhibiting autophagy and mediating the Notch1 signaling pathway (72, 73). Further research found that tubastatin A suppresses the ability of colony formation and migration, while in combination with temozolomide, tubastatin A accelerates glioblastoma cells apoptosis, and help glioblastoma multiforme cells overcome ER stress-tolerance (60, 74). Subsequent developed highly selective HDAC6 inhibitors including J22352, ACY1215 (Ricolinostat) and its analogue ACY241, JW-1, ACY1083 etc. come out one after another. Those small molecules present highly effective anti-cancer effects. Among them, ACY1215 and its analogue ACY241 appeared a good anti-tumor effect in synergy with other drugs (59, 61, 75). In particular, ACY1215 has already entered phase II treatment of multiple myeloma (76, 77), and ACY241 has been completed the phase I clinical trial in combination with paclitaxel in solid tumor models (66). In fact, more compounds are still in the experimental research stage. For example, J22352 as a highly HDAC6-selective inhibitor suppresses the proliferation as well as migration of glioblastoma through promoting the proteolysis degradation of HDAC6 and resulting in anti-cancer effect by inhibiting autophagy (71). It is worth noting that HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase, which mediates microtubule-dependent cell motility (78, 79). HDAC6 inhibitors JW-1, ACY1083 as well as tubastatin A anchor this characteristic of HDAC6. By inhibiting HDAC6, they can promote the acetylation of α-tubulin (80–82) thereby regulating cancer cell cycle and proliferation (74, 83, 84). HDAC6-selective inhibitor C1A exhibits an additional mechanism of action, inhibiting neuroblastoma and CRC xenograft growth through the modulation of autophagy substrates (85). While MPT0G211 targets HDAC6 thereby accelerates the acetylation of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90), further inhibits breast cancer metastasis (80). In combination with other anticancer drugs, HDAC6 inhibitor A542 suppresses the proliferation of follicular lymphoma (FL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), germinal center diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells (DLBCL) and CRC by targeting HDAC6 (86, 87). Furthermore, HDAC6 inhibitors such as JOC1, SKLB-23bb, MPT0G413 as well as MPT0G612 show great anticancer activity, whereas the cytoplasm toxic as well as the mechanism are to be further investigated (68, 88–91).

Sirtuins (SIRT1-7) are human homologs of the yeast Sir2 (silent information regulator-2) protein and are divided into four main classes: SIRT1-3 are class I, SIRT4 is class II, SIRT5 is class III and SIRT6-7 are class IV (92). SIRT proteins belong NAD-dependent deacetylases that act as intracellular regulators and are thought to have ADP-ribosyltransferase activity (93). It has been reported that (94–97) SIRT1 and SIRT2 as deacetylases modulate the acetylation of p53, thereby regulating p53 target genes and cancer cell progression (81, 98). JQ-101, which inhibits SIRT1-mediated H4K16 and p53 acetylation, thereby inducing A549 cell senescence and inhibiting tumor growth and invasiveness, similar phenomenon and mechanism has been detected in SIRT1 specific inhibitor EX527 treated glioma cells (82, 99). Moreover, AEM1 and AEM2 also can facilitate p53 acetylation by targeting SIRT2 and further regulating the expression of p53 target genes (e.g., cell cycle regulator p21), thereby sensitizing NSCLC cells to genotoxic stress (100). However, tenovin-6 modulates the mRNA and protein level of p21 in cancer cell lines but through a p53-independent mechanism (101–104).

Recently, with the development of HDAC inhibitors, many newly synthesized, derived derivatives or modified compounds have come out, and pre-clinical experiments have begun. For instance, a novel HDACi (OH-VPA) was developed by modifying a traditional HDACi (VPA), representing a new approach to novel HDACi development. The derivative HDACi is more effective in inhibiting HeLa cell proliferation than its parent molecule (105). In addition, many compounds are still in pre-clinical development, such as abexinostat, AR-42, chidamide, CHR-3996, CI-994, CUDC-101, CUDC-907, entinostat (MS-275), givinostat, MGCD0103, mocetinostat, phenylbutyrate, pivanex, pracinostat, quisinostat, ricolinostat, valproic acid (VPA). Some confer added benefits in combination with other drugs and are undergoing phase I/II clinical trials ( Table 1 ) (62, 65, 94–97, 102–104, 106–109, 112–120, 123–130, 132–135, 139–143, 175, 176).

Table 1.

Selective HDAC inhibitors in clinical trials (completed) (from clinicaltrials.gov as of October 2020).

| Compound | HDAC Selectivity | Clinical Trial Phase and Indication(s) | ID# of clinical trial | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abexinostat | Class I, II | Phase I for advanced solid tumors. | NCT01543763 | (106, 107) |

| Phase I/II for Hodgkin lymphoma. | NCT00724984 | |||

| Phase I/II for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. | NCT04024696 | |||

| Phase I/II for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. | NCT00724984 | |||

| Phase I, combined with doxorubicin, for metastatic sarcoma. | NCT01027910 | (108) | ||

| ACY241 | HDAC6 | Phase I, in combination with paclitaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors | NCT02551185 | (66) |

| Phase I, in combination with ipilimumab and nivolumab to patients with advanced melanoma. | NCT02935790 | – | ||

| AR-42 | Class I, IIb | Phase I for multiple myeloma and T- and B-cell lymphomas. | NCT01129193 | (109) |

| Phase I, in combination with decitabine in AML in adults and children. | NCT01798901 | (110, 111) | ||

| Belinostat | Class I, II, IV | FDA approved for peripheral T-cell lymphoma. | NCT00865969 | (94–97, 112, 113), |

| Phase I/II for lymphomas and solid tumors. | NCT01273155 | |||

| Phase I, combined with cisplatin and etoposide, for solid lung tumors. | NCT00926640 | (114–117), | ||

| Phase I/II, combined with doxorubicin, for soft tissue sarcomas. | NCT00878800 | |||

| Phase II, combined with paclitaxel/carboplatin, for carcinoma. | NCT00873119 | |||

| Phase I/II, combined with cisplatin, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide in thymic epithelial tumors. | NCT01100944 | |||

| Chidamide | HDAC1-3,10 | Phase II, combined with paclitaxel and carboplatin for advanced NSCLC. | NCT01836679 | (118) |

| CHR-3996 | Class I | Phase I for refractory solid tumors. | NCT00697879 | (102) |

| CI-994 | Class I | Phase II, with or without gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer. | NCT00004861 | (103) |

| Phase II for myeloma. | NCT00005624 | (104) | ||

| phase III with or without gemcitabine for advanced NSCLC. | NCT00005093 | (119) | ||

| CUDC-101 | Class I, II HDAC/EGFR/HER2 | Phase I for advanced solid tumors. | NCT00728793 | (120) |

| Phase Ib, for advanced head and neck, gastric, breast, liver, and non-small cell lung cancer tumors. | NCT01171924 | (121) | ||

| Phase I, in combination with concurrent cisplatin and radiation therapy in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. | NCT01384799 | (122) | ||

| CUDC-907 | Class I, II | Phase I for B-cell lymphoma. | NCT02674750 | (123) |

| Phase I, for advanced/relapsed solid tumors | NCT02307240 | – | ||

|

Entinostat

(MS-275) |

Class I | Phase I/II for RCC. | NCT03552380 | (124, 125), |

| Phase II for relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. | NCT00866333 | |||

| Phase II, combined with 5-azacitidine and entinostat, for advanced breast cancer and metastatic CRC. | NCT01105377 | (126, 127), | ||

| Phase I for advanced solid tumors or lymphoma. | NCT00020579 | (128–130) | ||

| Phase I/II, combined with avelumab for epithelial ovarian cancer. | NCT02915523 | |||

| Phase I, combined with exemestane, for breast cancer. | NCT02833155 | |||

| Phase II, combined with azacitidine, for metastatic CRC. | NCT01105377 | |||

| Phase I/II, combined with azacitidine, for recurrent advanced NSCLC. | NCT00387465 | |||

|

Givinostat

(ITF2357) |

Class I, II | Phase II, ITF2357 followed by Mechlorethamine administered to patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. | NCT00792467 | - (131) |

| Mocetinostat (MGCD0103) | Class I, IV | Phase I for advanced solid tumors or Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. | NCT00323934 | (132) |

| Phase I, combined with docetaxel for advanced solid tumors. | NCT00511576 | (133) | ||

| Phase II for relapsed/refractory lymphoma. | NCT00359086 | (134, 135) | ||

| Phase II, combined with gemcitabine, for metastatic leiomyosarcoma | NCT02303262 | (133) | ||

| Phase II, for advanced urothelial carcinoma. | NCT02236195 | (136) | ||

| Phase I/II, combined with durvalumab for advanced solid tumors and NSCLC | NCT02805660 | – | ||

| Phase II for refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia | NCT00431873 | (137) | ||

| Phase I for leukemia. | NCT00324194 | (138) | ||

| Phase I/II, in combination with azacitidine for AML. | NCT00324220 | – | ||

| Phase I/II, combined with gemcitabine for solid tumors. | NCT00372437 | (133) | ||

| Panobinostat | Class I, II, IV | FDA approved for multiple myeloma. | NCT02568943 | (139–141) |

| Phase II for lymphoma/waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. | NCT01261247 | |||

| Phase I/II, combined with bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone, for relapsed multiple myeloma. | NCT01023308 | (142) | ||

| Phenylbutyrate | Class I, II | Phase I for solid tumors or lymphomaa. | NCT00002909 | (143) |

| Phase I, combined with azacitidine, for refractory solid tumors. | NCT00005639 | (144) | ||

| Phase II, for brain tumors in children | NCT00006450 | – | ||

| Phase I, for brain neoplasms and neuroblastoma | NCT00001565 | – | ||

| Phase I, in combination with azacitidine for AML | NCT00004871 | (145) | ||

| Pivanex | Class I, II | Phase II, in combination with docetaxel for advanced NSCLC. | NCT00073385 | (146) |

|

Pracinostat

(SB939) |

Class I, II, IV | Phase I, treatment alone or with azacitidine for advanced solid tumors. | NCT00741234 | (147) |

| Phase I, combined with azacitidine for AML. | NCT01912274 | (148) | ||

| Phase I, for locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. | NCT00504296 | – | ||

| Phase I, for solid tumors and leukemia | NCT01184274 | – | ||

| Phase II, for recurrent or metastatic prostate cancer. | NCT01075308 | (149) | ||

| Phase II, for advanced or recurring sarcoma. | NCT01112384 | (150) | ||

|

Quisinostat

(JNJ-26481585) |

Class I, II | Phase I for advanced solid tumors and lymphoma. | NCT00677105 | (151) |

| Phase II, in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer, primarily peritoneal or fallopian tube carcinoma. | NCT02948075 | – | ||

| Phase II, for cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma. | NCT01486277 | (152) | ||

| Phase I, in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin for NSCLC, in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin for NSCLC and ovarian cancer | NCT02728492 | – | ||

| Phase I, in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma | NCT01464112 | (153) | ||

|

Ricolinostat

(ACY1215) |

HDAC6 | Phase Ib, ACY-1215 monotherapy in patients with lymphoid malignancies. | NCT02091063 | – |

| Phase Ib, combined with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. | NCT02189343 | (154) | ||

| Phase I and phase IIa, alone or in combination with bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. | NCT01323751 | (155) | ||

|

Romidepsin

(FK228) |

Class I | FDA approved for cutaneous/peripheral T-cell lymphoma. | NCT00007345 | (47, 156) |

| Phase I/II for Japanese patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. | NCT00426764 | |||

| Phase I, combined with ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide for relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. | NCT01590732 | (131, 157) | ||

| Phase I/II, combined with erlotinib hydrochloride, for lung cancer and metastatic cancer. | NCT01302808 | |||

| Phase I/II, combined with abraxane for metastatic inflammatory breast cancer. | NCT01938833 | |||

| Phase I/II, combined with cisplatin and nivolumab, for triple negative breast cancer. | NCT02393794 | |||

| Phase II for recurrent and/or metastatic thyroid cancer. | NCT00098813 | |||

| Phase I, combined with gemcitabine for pancreatic cancer. | NCT00379639 | |||

|

Valproic Acid

(VPA) |

Class I, II | Phase II for prostate cancer. | NCT00670046 | (158–160) |

| Phase II, combined with bevacizumab, mFOLFOX6/mOXXEL, Capecitabine,5-fluorouracil, for ras-mutated metastatic CRC. | NCT04310176 | |||

| Phase I, combined with azacitidine, for advanced cancers. | NCT00496444 | |||

| Phase I, combined with etoposide for neuronal tumors and brain metastases | NCT00513162 | |||

|

Vorinostat

(SAHA) |

Class I, II, IV | FDA approved for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. | NCT00958074 | (161) |

| Phase I, combined with isotretinoin, for refractory/recurrent neuroblastoma. | NCT01208454 | (54, 162, 163) | ||

| Phase II, combined with bevacizumab, for malignant glioma. | NCT01738646 | |||

| Phase I/II, combined with bevacizumab and temozolomide, for recurrent malignant gliomas. | NCT00939991 | |||

| Phase II, combined with MK0683 and vorinostat, for advanced cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. | NCT00091559 | (164–166) | ||

| Phase II for progressive metastatic prostate cancer. | NCT00330161 | (167, 168) | ||

| Phase II for progressive or recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. | NCT00238303 | (169) | ||

| Phase I/II for advanced BRAF mutated melanoma. | NCT02836548 | (170) | ||

| Phase II, combined with paclitaxel, carboplatin, placebo, for stage III or stage IV NSCLC. | NCT00481078 | (171) | ||

| Phase I/II, combined with pembrolizumab for squamous cell head and neck cancer or salivary gland cancer. | NCT02538510 | (172) | ||

| Phase I, combined with pazopanib for advanced cancer. | NCT01339871 | (173) | ||

| Phase I/II for multiple myeloma. | NCT00857324 | (174) |

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CRC, colorectal cancer; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer, RCC, renal cell carcinoma.

Small Molecules Targeting HATs

This review limits its scope to discussing only HAT inhibitors which have been approved for cancer therapy or commercialization, since the specific mechanisms of HAT modulation-mediated anti-cancer effects are complex and ambiguous (177, 178). It appears that HAT influence during carcinogenesis is context-specific because HATs are able to act as both oncogenes and tumor suppressors (179). The possible reason is that different tumors show mutations in different HAT members, which directly or indirectly affects any steps in the continuous process of tumor progression from tumorigenesis to carcinogenesis and metastasis (180). Based on sequence homology and shared structural features, HATs can be divided into two different classes. One is the GCN5-related N-acetyltransferases (GNATs) family, including GCN5 and p300/CBP-associating factor (PCAF), that can acetylate lysine residues on histones and non-histone proteins (181). In lung cancer cells, p300 may promote Snail-dependent EMT (epithelial-mesenchymal transition) by acetylating Snail at K187 site (182, 183). At present, several small molecule compounds targeting p300 have been developed and proved to have anti-cancer effects. For example, (184) Garcinol facilitate HeLa cell apoptosis via inhibiting the HAT activity of P300 and PCAF (185). Similarly, the molecule PU141, a selective CBP/P300 inhibitor, suppresses murine SK-N-SH neuroblastoma xenograft survival (186). Another HAT inhibitor C646 suppresses gastric cancer cell survival and invasive capability through competitively disrupting the interaction between Ac-CoA and CBP/P300 (187, 188). Recently discovered compounds CCT077791 and CCT077792 were also found to target P300 and PCAF, and resulting in the reduction of global acetylation level in colon tumor cell acetylation levels and inhibiting tumor cell growth (189).

Another HAT family is the MYST superfamily, exhibiting a conserved catalytic MYST domain, and large group membership, including MOZ, Ybf2, Sas2, TIP60, and hMOF (181). The role of MYST family in tumorigenesis is beyond doubt. Based on laboratory research data, Tip60 can harbor substrates including histones and non-histone proteins like p53 and ATM kinase, through which TIP60 plays critical roles in regulating cancer progression such as cell cycle, invasiveness and metastasis in gastric cancer and breast cancer cells (190, 191). Importantly, changes of downregulation of TIP60 is correlated with overall survival of breast cancer patients (42, 192). In addition, by regulating PI3K/AKT pathway, Tip60 suppresses the proliferation and migration of cholangiocarcinoma (111, 193)Given the critical role of TIP60 (a HAT which forms part of the TIP60/NuA4 complex) in DNA damage repair, several TIP60 inhibitors have been investigated for their anti-cancer therapeutic potential, including TH1834, NU9056, and 6-alkylsalicylates. Indeed, TH1834 (which blocks the binding site of TIP60) disrupts DNA damage repair to induce breast cancer cell apoptosis (194), and NU9056 both inhibits prostate cancer cell growth and induces apoptosis (195). Similarly, frequent downregulation of MOF has been detected in numerous cancers, including RCC, ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, and CRC (33). Developed MOF inhibitor DC-M01-7 downregulates H4K16ac, inhibiting proliferation of human colon cancer (HCT116) cells (196). Furthermore, through the role of HATs in DNA damage repair, several novel HAT inhibitors sensitize cancer cells to the cytotoxic effects of radiation therapy, suggesting their potential as adjuvants in this context (197, 198). However, there are few reports on selective inhibitors targeting members of this family.

BRD Inhibitors

It is common for both histone acetylation and BRDs to become dysregulated in cancer. Current BRD inhibitors (e.g., isoxazoles, purines, quinolinones, tetrahydroquinolines, naphthyridines, and acetylated lysine analogs) exhibit high affinity and specificity for the BET bromine domain (199). Both I-BET 151 and I-BET 762 down-regulate c-Myc transcription, result in inhibition of myeloma cell proliferation (177). Moreover, I-BET 762 suppresses pancreatic cancer cell proliferation (178), and I-BET 762 inhibits breast and lung cancer cell proliferation through cell growth arrest and immune modulation (200). Whereas another BRD inhibitor JO1, by competing with histone acetylated residues, releases BRD4 from chromatin, thereby modulating RNA-Pol II activity to regulate the transcription of key cancer-associated genes (201). In addition, JQ1 decreases the acetylation level and activity of mutant p53, inducing cell growth arrest and subsequent senescence in HNSCC (202). OTX015 (MK-8628, birabresib), one of BRD and extra-terminal domain inhibitors, exhibits antitumor activity in medulloblastoma, B-cell lymphoma, and lung cancer (179, 184, 203). In addition, BET inhibitors such like PLX51107 and NHWD-870 have been identified the activity of tumor proliferation suppression (204, 205). By targeting the interaction of BRDs and acetylated lysine residues on histone, BRD inhibitors modulate chromosome structure and cancer-associated gene expression including c-Myc.

Conclusions and Perspectives

Altered histone acetylation—one of the earliest-identified and best-studied epigenetic modifications—is associated with tumorigenesis and tumor progression. Aberrant acetylation profiles are present across various cancer cells, tissues, and types. Given that dynamic histone acetylation/deacetylation is regulated by HDACs, HATs, and BRDs, many small molecules and novel synthesized compounds targeting enzyme catalytic activity or BRD/histone interaction are under investigation for their anti-cancer therapeutic potential ( Figure 3 ). While several agents are already FDA-approved for clinical use, many more are undergoing clinical trials, and additional novel agents are being developed and tested. Indeed, the full clinical therapeutic scope and commercial value of such agents in the field of oncology is only just emerging.

Figure 3.

Links between histone acetylation level and cell cycle/cancer progression.

Author Contributions

ZQ and DL designed the review. DW, YQ, ZQ, YJ, and DL contributed to manuscript preparation. DW and YQ contributed equally. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81572868, 81803680, 81973712, 81903876). Jilin Scientific and Technological Development Program (Grant No. 20170309005YY).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing; Miss Mo Bai for figures editing.

References

- 1. Rando OJ, Chang HY. Genome-wide views of chromatin structure. Annu Rev Biochem (2009) 78:245–71. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.071107.134639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pal S, Tyler JK. Epigenetics and aging. Sci Adv (2016) 2:e1600584. 10.1126/sciadv.1600584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verdone L, Agricola E, Caserta M, Di Mauro E. Histone acetylation in gene regulation. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic (2006) 5:209–21. 10.1093/bfgp/ell028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen H, Tini M, Evans RM. HATs on and beyond chromatin. Curr Opin Cell Biol (2001) 13:218–24. 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00200-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gebremedhin KG, Rademacher DJ. Histone H3 acetylation in the postmortem Parkinson’s disease primary motor cortex. Neurosci Lett (2016) 627:121–5. 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.05.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang C, Zhong JF, Stucky A, Chen XL, Press MF, Zhang X. Histone acetylation: novel target for the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Epigenet (2015) 7:117. 10.1186/s13148-015-0151-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ververis K, Hiong A, Karagiannis TC, Licciardi PV. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACIs): multitargeted anticancer agents. Biologics (2013) 7:47–60. 10.2147/BTT.S29965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Di Cerbo V, Schneider R. Cancers with wrong HATs: the impact of acetylation. Briefings Funct Genomics (2013) 12:231–43. 10.1093/bfgp/els065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tafrova JI, Tafrov ST. Human histone acetyltransferase 1 (Hat1) acetylates lysine 5 of histone H2A in vivo. Mol Cell Biochem (2014) 392:259–72. 10.1007/s11010-014-2036-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xu X, Yu H, Xu Y. Ras-ERK1/2 Signaling Promotes The Development Of Osteosarcoma By Regulating H2BK12ac Through CBP. Cancer Manag Res (2019) 11:9153–63. 10.2147/CMAR.S219535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumar V, Rayan NA, Muratani M, Lim S, Elanggovan B, Xin L, et al. Comprehensive benchmarking reveals H2BK20 acetylation as a distinctive signature of cell-state-specific enhancers and promoters. Genome Res (2016) 26:612–23. 10.1101/gr.201038.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hashimoto T, Yamakawa M, Kimura S, Usuba O, Toyono M. Expression of acetylated and dimethylated histone H3 in colorectal cancer. Dig Surg (2013) 30:249–58. 10.1159/000351444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen YW, Kao SY, Wang HJ, Yang MH. Histone modification patterns correlate with patient outcome in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer (2013) 119:4259–67. 10.1002/cncr.28356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhen L, Gui-lan L, Ping Y, Jin H, Ya-li W. The expression of H3K9Ac, H3K14Ac, and H4K20TriMe in epithelial ovarian tumors and the clinical significance. Int J Gynecol Cancer (2010) 20:82–6. 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181ae3efa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mohamed MA, Greif PA, Diamond J, Sharaf O, Maxwell P, Montironi R, et al. Epigenetic events, remodelling enzymes and their relationship to chromatin organization in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic adenocarcinoma. BJU Int (2007) 99:908–15. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Judes G, Dagdemir A, Karsli-Ceppioglu S, Lebert A, Echegut M, Ngollo M, et al. H3K4 acetylation, H3K9 acetylation and H3K27 methylation in breast tumor molecular subtypes. Epigenomics (2016) 8:909–24. 10.2217/epi-2016-0015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Messier TL, Gordon JA, Boyd JR, Tye CE, Browne G, Stein JL, et al. Histone H3 lysine 4 acetylation and methylation dynamics define breast cancer subtypes. Oncotarget (2016) 7:5094–109. 10.18632/oncotarget.6922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang JQ, Yan FQ, Wang LH, Yin WJ, Chang TY, Liu JP, et al. Identification of new hypoxia-regulated epithelial-mesenchymal transition marker genes labeled by H3K4 acetylation. Genes Chromosomes Cancer (2020) 59:73–83. 10.1002/gcc.22802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ma L, Yuan L, An J, Barton MC, Zhang Q, Liu Z. Histone H3 lysine 23 acetylation is associated with oncogene TRIM24 expression and a poor prognosis in breast cancer. Tumour Biol J Int Soc Oncodevelopmental Biol Med (2016) 37:14803–12. 10.1007/s13277-016-5344-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karczmarski J, Rubel T, Paziewska A, Mikula M, Bujko M, Kober P, et al. Histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation is altered in colon cancer. Clin Proteomics (2014) 11:24. 10.1186/1559-0275-11-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Y, Chen X, Tang G, Liu D, Peng G, Ma W, et al. AS-IL6 promotes glioma cell invasion by inducing H3K27Ac enrichment at the IL6 promoter and activating IL6 transcription. FEBS Lett (2016) 590:4586–93. 10.1002/1873-3468.12485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang E, Han L, Yin D, He X, Hong L, Si X, et al. H3K27 acetylation activated-long non-coding RNA CCAT1 affects cell proliferation and migration by regulating SPRY4 and HOXB13 expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nucleic Acids Res (2017) 45:3086–101. 10.1093/nar/gkw1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Seligson DB, Horvath S, McBrian MA, Mah V, Yu H, Tze S, et al. Global levels of histone modifications predict prognosis in different cancers. Am J Pathol (2009) 174:1619–28. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Juliano CN, Izetti P, Pereira MP, Dos Santos AP, Bravosi CP, Abujamra AL, et al. H4K12 and H3K18 Acetylation Associates With Poor Prognosis in Pancreatic Cancer. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol (2016) 24:337–44. 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Y, Li S, Chen J, Shao T, Jiang C, Wang Y, et al. Comparative epigenetic analyses reveal distinct patterns of oncogenic pathways activation in breast cancer subtypes. Hum Mol Genet (2014) 23:5378–93. 10.1093/hmg/ddu256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pfister S, Rea S, Taipale M, Mendrzyk F, Straub B, Ittrich C, et al. The histone acetyltransferase hMOF is frequently downregulated in primary breast carcinoma and medulloblastoma and constitutes a biomarker for clinical outcome in medulloblastoma. Int J Cancer (2008) 122:1207–13. 10.1002/ijc.23283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cao L, Zhu L, Yang J, Su J, Ni J, Du Y, et al. Correlation of low expression of hMOF with clinicopathological features of colorectal carcinoma, gastric cancer and renal cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol (2014) 44:1207–14. 10.3892/ijo.2014.2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang Y, Zhang R, Wu D, Lu Z, Sun W, Cai Y, et al. Epigenetic change in kidney tumor: downregulation of histone acetyltransferase MYST1 in human renal cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res (2013) 32:8. 10.1186/1756-9966-32-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu N, Zhang R, Zhao X, Su J, Bian X, Ni J, et al. A potential diagnostic marker for ovarian cancer: Involvement of the histone acetyltransferase, human males absent on the first. Oncol Lett (2013) 6:393–400. 10.3892/ol.2013.1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cai M, Hu Z, Liu J, Gao J, Tan M, Zhang D, et al. Expression of hMOF in different ovarian tissues and its effects on ovarian cancer prognosis. Oncol Rep (2015) 33:685–92. 10.3892/or.2014.3649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhao L, Wang DL, Liu Y, Chen S, Sun FL. Histone acetyltransferase hMOF promotes S phase entry and tumorigenesis in lung cancer. Cell Signal (2013) 25:1689–98. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen Z, Ye X, Tang N, Shen S, Li Z, Niu X, et al. The histone acetylranseferase hMOF acetylates Nrf2 and regulates anti-drug responses in human non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Pharmacol (2014) 171:3196–211. 10.1111/bph.12661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sauer T, Arteaga MF, Isken F, Rohde C, Hebestreit K, Mikesch JH, et al. MYST2 acetyltransferase expression and Histone H4 Lysine acetylation are suppressed in AML. Exp Hematol (2015) 43:794–802 e4. 10.1016/j.exphem.2015.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Suzuki J, Chen YY, Scott GK, Devries S, Chin K, Benz CC, et al. Protein acetylation and histone deacetylase expression associated with malignant breast cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res (2009) 15:3163–71. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kaimori JY, Maehara K, Hayashi-Takanaka Y, Harada A, Fukuda M, Yamamoto S, et al. Histone H4 lysine 20 acetylation is associated with gene repression in human cells. Sci Rep (2016) 6:24318. 10.1038/srep24318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Iizuka M, Smith MM. Functional consequences of histone modifications. Curr Opin Genet Dev (2003) 13:154–60. 10.1016/S0959-437X(03)00020-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johnstone RW. Histone-deacetylase inhibitors: novel drugs for the treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discovery (2002) 1:287–99. 10.1038/nrd772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Duan Y, Guan Y, Qin W, Zhai X, Yu B, Liu H. Targeting Brd4 for cancer therapy: inhibitors and degraders. Med Chem Comm (2018) 9:1779–802. 10.1039/C8MD00198G [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zaware N, Zhou MM. Bromodomain biology and drug discovery. Nat Struct Mol Biol (2019) 26:870–9. 10.1038/s41594-019-0309-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang P, Dong Z, Cai J, Zhang C, Shen Z, Ke A, et al. BRD4 promotes tumor growth and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol (2015) 28:36–44. 10.1177/0394632015572070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khoueiry P, Ward Gahlawat A, Petretich M, Michon AM, Simola D, Lam E, et al. BRD4 bimodal binding at promoters and drug-induced displacement at Pol II pause sites associates with I-BET sensitivity. Epigenet Chromatin (2019) 12:39. 10.1186/s13072-019-0286-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sakuraba K, Yokomizo K, Shirahata A, Goto T, Saito M, Ishibashi K, et al. TIP60 as a potential marker for the malignancy of gastric cancer. Anticancer Res (2011) 31:77–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Singh S, Kumar PU, Thakur S, Kiran S, Sen B, Sharma S, et al. Expression/localization patterns of sirtuins (SIRT1, SIRT2, and SIRT7) during progression of cervical cancer and effects of sirtuin inhibitors on growth of cervical cancer cells. Tumour Biol J Int Soc Oncodevelopmental Biol Med (2015) 36:6159–71. 10.1007/s13277-015-3300-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cha EJ, Noh SJ, Kwon KS, Kim CY, Park BH, Park HS, et al. Expression of DBC1 and SIRT1 is associated with poor prognosis of gastric carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res (2009) 15:4453–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim JK, Noh JH, Jung KH, Eun JW, Bae HJ, Kim MG, et al. Sirtuin7 oncogenic potential in human hepatocellular carcinoma and its regulation by the tumor suppressors MiR-125a-5p and MiR-125b. Hepatology (2013) 57:1055–67. 10.1002/hep.26101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Evans LW, Ferguson BS. Food Bioactive HDAC Inhibitors in the Epigenetic Regulation of Heart Failure. Nutrients (2018) 10(8):1120. 10.3390/nu10081120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li Y, Seto E. HDACs and HDAC Inhibitors in Cancer Development and Therapy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med (2016) 6(10):a026831. 10.1101/cshperspect.a026831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rashidi A, Cashen AF. Belinostat for the treatment of relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Future Oncol (2015) 11:1659–64. 10.2217/fon.15.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ding L, Zhang W, Yang L, Pelicano H, Zhou K, Yin R, et al. Targeting the autophagy in bone marrow stromal cells overcomes resistance to vorinostat in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. OncoTargets Ther (2018) 11:5151–70. 10.2147/OTT.S170392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Foggetti G, Ottaggio L, Russo D, Mazzitelli C, Monti P, Degan P, et al. Autophagy induced by SAHA affects mutant P53 degradation and cancer cell survival. Biosci Rep (2019) 39(2):BSR20181345. 10.1042/BSR20181345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wu Z, Jing S, Li Y, Gao Y, Yu S, Li Z, et al. The effects of SAHA on radiosensitivity in pancreatic cancer cells by inducing apoptosis and targeting RAD51. BioMed Pharmacother (2017) 89:705–10. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.02.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liao B, Zhang Y, Sun Q, Jiang P. Vorinostat enhances the anticancer effect of oxaliplatin on hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Med (2018) 7:196–207. 10.1002/cam4.1278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Civallero M, Cosenza M, Pozzi S, Sacchi S. Ruxolitinib combined with vorinostat suppresses tumor growth and alters metabolic phenotype in hematological diseases. Oncotarget (2017) 8:103797–814. 10.18632/oncotarget.21951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pinto N, DuBois SG, Marachelian A, Diede SJ, Taraseviciute A, Glade Bender JL, et al. Phase I study of vorinostat in combination with isotretinoin in patients with refractory/recurrent neuroblastoma: A new approaches to Neuroblastoma Therapy (NANT) trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer (2018) 65:e27023. 10.1002/pbc.27023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bolden JE, Shi W, Jankowski K, Kan CY, Cluse L, Martin BP, et al. HDAC inhibitors induce tumor-cell-selective pro-apoptotic transcriptional responses. Cell Death Dis (2013) 4:e519. 10.1038/cddis.2013.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Oh ET, Park MT, Choi BH, Ro S, Choi EK, Jeong SY, et al. Novel histone deacetylase inhibitor CG200745 induces clonogenic cell death by modulating acetylation of p53 in cancer cells. Invest New Drugs (2012) 30:435–42. 10.1007/s10637-010-9568-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hwang JJ, Kim YS, Kim T, Kim MJ, Jeong IG, Lee JH, et al. A novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, CG200745, potentiates anticancer effect of docetaxel in prostate cancer via decreasing Mcl-1 and Bcl-XL. Invest New Drugs (2012) 30:1434–42. 10.1007/s10637-011-9718-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chun SM, Lee JY, Choi J, Lee JH, Hwang JJ, Kim CS, et al. Epigenetic modulation with HDAC inhibitor CG200745 induces anti-proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer cells. PloS One (2015) 10:e0119379. 10.1371/journal.pone.0119379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee JH, Mahendran A, Yao Y, Ngo L, Venta-Perez G, Choy ML, et al. Development of a histone deacetylase 6 inhibitor and its biological effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2013) 110:15704–9. 10.1073/pnas.1313893110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Li ZY, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Chen L, Chen BD, Li QZ, et al. A novel HDAC6 inhibitor Tubastatin A: Controls HDAC6-p97/VCP-mediated ubiquitination-autophagy turnover and reverses Temozolomide-induced ER stress-tolerance in GBM cells. Cancer Lett (2017) 391:89–99. 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kaliszczak M, Trousil S, Åberg O, Perumal M, Nguyen QD, Aboagye EO. A novel small molecule hydroxamate preferentially inhibits HDAC6 activity and tumour growth. Br J Cancer (2013) 108:342–50. 10.1038/bjc.2012.576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lee HS, Park SB, Kim SA, Kwon SK, Cha H, Lee DY, et al. A novel HDAC inhibitor, CG200745, inhibits pancreatic cancer cell growth and overcomes gemcitabine resistance. Sci Rep (2017) 7:41615. 10.1038/srep41615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jung DE, Park SB, Kim K, Kim C, Song SY. CG200745, an HDAC inhibitor, induces anti-tumour effects in cholangiocarcinoma cell lines via miRNAs targeting the Hippo pathway. Sci Rep (2017) 7:10921. 10.1038/s41598-017-11094-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Park SE, Kim HG, Kim DE, Jung YJ, Kim Y, Jeong SY, et al. Combination treatment with docetaxel and histone deacetylase inhibitors downregulates androgen receptor signaling in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Invest New Drugs (2018) 36:195–205. 10.1007/s10637-017-0529-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kim KP, Park SJ, Kim JE, Hong YS, Lee JL, Bae KS, et al. First-in-human study of the toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of CG200745, a pan-HDAC inhibitor, in patients with refractory solid malignancies. Invest New Drugs (2015) 33:1048–57. 10.1007/s10637-015-0262-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Huang P, Almeciga-Pinto I, Jarpe M, van Duzer JH, Mazitschek R, Yang M, et al. Selective HDAC inhibition by ACY-241 enhances the activity of paclitaxel in solid tumor models. Oncotarget (2017) 8:2694–707. 10.18632/oncotarget.13738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Subramanian S, Bates SE, Wright JJ, Espinoza-Delgado I, Piekarz RL. Clinical Toxicities of Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) (2010) 3:2751–67. 10.3390/ph3092751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang F, Zheng L, Yi Y, Yang Z, Qiu Q, Wang X, et al. SKLB-23bb, A HDAC6-Selective Inhibitor, Exhibits Superior and Broad-Spectrum Antitumor Activity via Additionally Targeting Microtubules. Mol Cancer Ther (2018) 17:763–75. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-0332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang X, Yuan Z, Zhang Y, Yong S, Salas-Burgos A, Koomen J, et al. HDAC6 modulates cell motility by altering the acetylation level of cortactin. Mol Cell (2007) 27:197–213. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Hao M, Song F, Du X, Wang G, Yang Y, Chen K, et al. Advances in targeted therapy for unresectable melanoma: new drugs and combinations. Cancer Lett (2015) 359:1–8. 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.12.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Liu JR, Yu CW, Hung PY, Hsin LW, Chern JW. High-selective HDAC6 inhibitor promotes HDAC6 degradation following autophagy modulation and enhanced antitumor immunity in glioblastoma. Biochem Pharmacol (2019) 163:458–71. 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.03.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yin C, Li P. Growth Suppression of Glioma Cells Using HDAC6 Inhibitor, Tubacin. Open Med (Warsaw Poland) (2018) 13:221–6. 10.1515/med-2018-0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Deskin B, Yin Q, Zhuang Y, Saito S, Shan B, Lasky JA. Inhibition of HDAC6 Attenuates Tumor Growth of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Transl Oncol (2020) 13:135–45. 10.1016/j.tranon.2019.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Urdiciain A, Erausquin E, Meléndez B, Rey JA, Idoate MA, Castresana JS. Tubastatin A, an inhibitor of HDAC6, enhances temozolomide−induced apoptosis and reverses the malignant phenotype of glioblastoma cells. Int J Oncol (2019) 54:1797–808. 10.3892/ijo.2019.4739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hideshima T, Qi J, Paranal RM, Tang W, Greenberg E, West N, et al. Discovery of selective small-molecule HDAC6 inhibitor for overcoming proteasome inhibitor resistance in multiple myeloma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2016) 113:13162–7. 10.1073/pnas.1608067113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Santo L, Hideshima T, Kung AL, Tseng JC, Tamang D, Yang M, et al. Preclinical activity, pharmacodynamic, and pharmacokinetic properties of a selective HDAC6 inhibitor, ACY-1215, in combination with bortezomib in multiple myeloma. Blood (2012) 119:2579–89. 10.1182/blood-2011-10-387365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Amengual JE, Johannet P, Lombardo M, Zullo K, Hoehn D, Bhagat G, et al. Dual Targeting of Protein Degradation Pathways with the Selective HDAC6 Inhibitor ACY-1215 and Bortezomib Is Synergistic in Lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res (2015) 21:4663–75. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Miyake Y, Keusch JJ, Wang L, Saito M, Hess D, Wang X, et al. Structural insights into HDAC6 tubulin deacetylation and its selective inhibition. Nat Chem Biol (2016) 12:748–54. 10.1038/nchembio.2140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hubbert C, Guardiola A, Shao R, Kawaguchi Y, Ito A, Nixon A, et al. HDAC6 is a microtubule-associated deacetylase. Nature (2002) 417:455–8. 10.1038/417455a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Hsieh YL, Tu HJ, Pan SL, Liou JP, Yang CR. Anti-metastatic activity of MPT0G211, a novel HDAC6 inhibitor, in human breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res (2019) 1866:992–1003. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lau AW, Liu P, Inuzuka H, Gao D. SIRT1 phosphorylation by AMP-activated protein kinase regulates p53 acetylation. Am J Cancer Res (2014) 4:245–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Zhu L, Qi J, Chiao CY, Zhang Q, Porco JA, Jr., Faller DV, et al. Identification of a novel polyprenylated acylphloroglucinolderived SIRT1 inhibitor with cancerspecific anti-proliferative and invasion-suppressing activities. Int J Oncol (2014) 45:2128–36. 10.3892/ijo.2014.2639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ho YH, Wang KJ, Hung PY, Cheng YS, Liu JR, Fung ST, et al. A highly HDAC6-selective inhibitor acts as a fluorescent probe. Org Biomol Chem (2018) 16:7820–32. 10.1039/C8OB00966J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Krukowski K, Ma J, Golonzhka O, Laumet GO, Gutti T, van Duzer JH, et al. HDAC6 inhibition effectively reverses chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain (2017) 158:1126–37. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kaliszczak M, van Hechanova E, Li Y, Alsadah H, Parzych K, Auner HW, et al. The HDAC6 inhibitor C1A modulates autophagy substrates in diverse cancer cells and induces cell death. Br J Cancer (2018) 119(10):1278–87. 10.1038/s41416-018-0232-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lee DH, Kim GW, Kwon SH. The HDAC6-selective inhibitor is effective against non-Hodgkin lymphoma and synergizes with ibrutinib in follicular lymphoma. Mol Carcinog (2019) 58:944–56. 10.1002/mc.22983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Won HR, Ryu HW, Shin DH, Yeon SK, Lee DH, Kwon SH. A452, an HDAC6-selective inhibitor, synergistically enhances the anticancer activity of chemotherapeutic agents in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Carcinog (2018) 57:1383–95. 10.1002/mc.22852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Auzmendi-Iriarte J, Saenz-Antoñanzas A, Mikelez-Alonso I, Carrasco-Garcia E, Tellaetxe-Abete M, Lawrie CH, et al. Characterization of a new small-molecule inhibitor of HDAC6 in glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis (2020) 11:417. 10.1038/s41419-020-2586-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Dong J, Zheng N, Wang X, Tang C, Yan P, Zhou HB, et al. A novel HDAC6 inhibitor exerts an anti-cancer effect by triggering cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Eur J Pharmacol (2018) 828:67–79. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Huang FI, Wu YW, Sung TY, Liou JP, Lin MH, Pan SL, et al. MPT0G413, A Novel HDAC6-Selective Inhibitor, and Bortezomib Synergistically Exert Anti-tumor Activity in Multiple Myeloma Cells. Front Oncol (2019) 9:249. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Chen MC, Lin YC, Liao YH, Liou JP, Chen CH. MPT0G612, a Novel HDAC6 Inhibitor, Induces Apoptosis and Suppresses IFN-γ-Induced Programmed Death-Ligand 1 in Human Colorectal Carcinoma Cells. Cancers (Basel) (2019) 11(10):1617. 10.3390/cancers11101617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Michan S, Sinclair D. Sirtuins in mammals: insights into their biological function. Biochem J (2007) 404:1–13. 10.1042/BJ20070140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Kida Y, Goligorsky MS. Sirtuins, Cell Senescence, and Vascular Aging. Can J Cardiol (2016) 32:634–41. 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Puvvada SD, Guillen-Rodriguez JM, Rivera XI, Heard K, Inclan L, Schmelz M, et al. A Phase II Exploratory Study of PXD-101 (Belinostat) Followed by Zevalin in Patients with Relapsed Aggressive High-Risk Lymphoma. Oncology (2017) 93:401–5. 10.1159/000479230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Bailey H, McPherson JP, Bailey EB, Werner TL, Gupta S, Batten J, et al. A phase I study to determine the pharmacokinetics and urinary excretion of belinostat and metabolites in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol (2016) 78:1059–71. 10.1007/s00280-016-3167-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Puvvada SD, Li H, Rimsza LM, Bernstein SH, Fisher RI, LeBlanc M, et al. A phase II study of belinostat (PXD101) in relapsed and refractory aggressive B-cell lymphomas: SWOG S0520. Leukemia Lymphoma (2016) 57:2359–69. 10.3109/10428194.2015.1135431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. McDermott J, Jimeno A. Belinostat for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Drugs Today (Barcelona Spain 1998) (2014) . 50:337–45. 10.1358/dot.2014.50.5.2138703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. van Leeuwen IM, Higgins M, Campbell J, McCarthy AR, Sachweh MC, Navarro AM, et al. Modulation of p53 C-terminal acetylation by mdm2, p14ARF, and cytoplasmic SirT2. Mol Cancer Ther (2013) 12:471–80. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wang T, Li X, Sun SL. EX527, a Sirt-1 inhibitor, induces apoptosis in glioma via activating the p53 signaling pathway. Anticancer Drugs (2020) 31:19–26. 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Hoffmann G, Breitenbucher F, Schuler M, Ehrenhofer-Murray AE. A novel sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) inhibitor with p53-dependent pro-apoptotic activity in non-small cell lung cancer. J Biol Chem (2014) 289:5208–16. 10.1074/jbc.M113.487736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. McCarthy AR, Sachweh MC, Higgins M, Campbell J, Drummond CJ, van Leeuwen IM, et al. Tenovin-D3, a novel small-molecule inhibitor of sirtuin SirT2, increases p21 (CDKN1A) expression in a p53-independent manner. Mol Cancer Ther (2013) 12:352–60. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Banerji U, van Doorn L, Papadatos-Pastos D, Kristeleit R, Debnam P, Tall M, et al. A phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of CHR-3996, an oral class I selective histone deacetylase inhibitor in refractory solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2012) 18:2687–94. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ma YT, Leonard SM, Gordon N, Anderton J, James C, Huen D, et al. Use of a genome-wide haploid genetic screen to identify treatment predicting factors: a proof-of-principle study in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget (2017) 8:63635–45. 10.18632/oncotarget.18879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Tandon N, Ramakrishnan V, Kumar SK. Clinical use and applications of histone deacetylase inhibitors in multiple myeloma. Clin Pharmacol (2016) 8:35–44. 10.2147/CPAA.S94021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Prestegui-Martel B, Bermudez-Lugo JA, Chavez-Blanco A, Duenas-Gonzalez A, Garcia-Sanchez JR, Perez-Gonzalez OA, et al. N-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-2-propylpentanamide, a valproic acid aryl derivative designed in silico with improved anti-proliferative activity in HeLa, rhabdomyosarcoma and breast cancer cells. J Enzyme Inhibit Medicinal Chem (2016) 31:140–9. 10.1080/14756366.2016.1210138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Deutsch E, Moyal EC, Gregorc V, Zucali PA, Menard J, Soria JC, et al. A phase 1 dose-escalation study of the oral histone deacetylase inhibitor abexinostat in combination with standard hypofractionated radiotherapy in advanced solid tumors. Oncotarget (2017) 8:56199–209. 10.18632/oncotarget.14147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Morschhauser F, Terriou L, Coiffier B, Bachy E, Varga A, Kloos I, et al. Phase 1 study of the oral histone deacetylase inhibitor abexinostat in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Invest New Drugs (2015) 33:423–31. 10.1007/s10637-015-0206-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Choy E, Flamand Y, Balasubramanian S, Butrynski JE, Harmon DC, George S, et al. Phase 1 study of oral abexinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, in combination with doxorubicin in patients with metastatic sarcoma. Cancer (2015) 121:1223–30. 10.1002/cncr.29175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Sborov DW, Canella A, Hade EM, Mo X, Khountham S, Wang J, et al. A phase 1 trial of the HDAC inhibitor AR-42 in patients with multiple myeloma and T- and B-cell lymphomas. Leukemia Lymphoma (2017) 58:2310–8. 10.1080/10428194.2017.1298751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Mims A, Walker AR, Huang X, Sun J, Wang H, Santhanam R, et al. Increased anti-leukemic activity of decitabine via AR-42-induced upregulation of miR-29b: a novel epigenetic-targeting approach in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia (2013) 27:871–8. 10.1038/leu.2012.342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Liva SG, Coss CC, Wang J, Blum W, Klisovic R, Bhatnagar B, et al. Phase I study of AR-42 and decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma (2020) 61:1484–92. 10.1080/10428194.2020.1719095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. O’Connor OA, Horwitz S, Masszi T, Van Hoof A, Brown P, Doorduijn J, et al. Belinostat in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Peripheral T-Cell Lymphoma: Results of the Pivotal Phase II BELIEF (CLN-19) Study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol (2015) 33:2492–9. 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.2782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Giaccone G, Rajan A, Berman A, Kelly RJ, Szabo E, Lopez-Chavez A, et al. Phase II study of belinostat in patients with recurrent or refractory advanced thymic epithelial tumors. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol (2011) 29:2052–9. 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Balasubramaniam S, Redon CE, Peer CJ, Bryla C, Lee MJ, Trepel JB, et al. Phase I trial of belinostat with cisplatin and etoposide in advanced solid tumors, with a focus on neuroendocrine and small cell cancers of the lung. Anti-cancer Drugs (2018) 29:457–65. 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Vitfell-Rasmussen J, Judson I, Safwat A, Jones RL, Rossen PB, Lind-Hansen M, et al. A Phase I/II Clinical Trial of Belinostat (PXD101) in Combination with Doxorubicin in Patients with Soft Tissue Sarcomas. Sarcoma (2016) 2016:2090271. 10.1155/2016/2090271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Hainsworth JD, Daugaard G, Lesimple T, Hubner G, Greco FA, Stahl MJ, et al. Paclitaxel/carboplatin with or without belinostat as empiric first-line treatment for patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site: A randomized, phase 2 trial. Cancer (2015) 121:1654–61. 10.1002/cncr.29229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Thomas A, Rajan A, Szabo E, Tomita Y, Carter CA, Scepura B, et al. A phase I/II trial of belinostat in combination with cisplatin, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide in thymic epithelial tumors: a clinical and translational study. Clin Cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2014) 20:5392–402. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Hu X, Wang L, Lin L, Han X, Dou G, Meng Z, et al. A phase I trial of an oral subtype-selective histone deacetylase inhibitor, chidamide, in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Chin J Cancer Res (2016) 28:444–51. 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2016.04.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Chidambaram A, Sundararaju K, Chidambaram RK, Subbiah R, Jayaraj JM, Muthusamy K, et al. Design, synthesis, and characterization of α, β-unsaturated carboxylic acid, and its urea based derivatives that explores novel epigenetic modulators in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell line. J Cell Physiol (2018) 233:5293–309. 10.1002/jcp.26333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Shimizu T, LoRusso PM, Papadopoulos KP, Patnaik A, Beeram M, Smith LS, et al. Phase I first-in-human study of CUDC-101, a multitargeted inhibitor of HDACs, EGFR, and HER2 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2014) 20:5032–40. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Wang J, Pursell NW, Samson ME, Atoyan R, Ma AW, Selmi A, et al. Potential advantages of CUDC-101, a multitargeted HDAC, EGFR, and HER2 inhibitor, in treating drug resistance and preventing cancer cell migration and invasion. Mol Cancer Ther (2013) 12:925–36. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Galloway TJ, Wirth LJ, Colevas AD, Gilbert J, Bauman JE, Saba NF, et al. A Phase I Study of CUDC-101, a Multitarget Inhibitor of HDACs, EGFR, and HER2, in Combination with Chemoradiation in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res (2015) 21:1566–73. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Oki Y, Kelly KR, Flinn I, Patel MR, Gharavi R, Ma A, et al. CUDC-907 in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, including patients with MYC-alterations: results from an expanded phase I trial. Haematologica (2017) 102:1923–30. 10.3324/haematol.2017.172882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Pili R, Quinn DI, Hammers HJ, Monk P, George S, Dorff TB, et al. Immunomodulation by Entinostat in Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients Receiving High-Dose Interleukin 2: A Multicenter, Single-Arm, Phase I/II Trial (NCI-CTEP#7870). Clin Cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2017) 23:7199–208. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Batlevi CL, Kasamon Y, Bociek RG, Lee P, Gore L, Copeland A, et al. ENGAGE- 501: phase II study of entinostat (SNDX-275) in relapsed and refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Haematologica (2016) 101:968–75. 10.3324/haematol.2016.142406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Connolly RM, Li H, Jankowitz RC, Zhang Z, Rudek MA, Jeter SC, et al. Combination Epigenetic Therapy in Advanced Breast Cancer with 5-Azacitidine and Entinostat: A Phase II National Cancer Institute/Stand Up to Cancer Study. Clin Cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2017) 23:2691–701. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Azad NS, El-Khoueiry A, Yin J, Oberg AL, Flynn P, Adkins D, et al. Combination epigenetic therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) with subcutaneous 5-azacitidine and entinostat: a phase 2 consortium/stand up 2 cancer study. Oncotarget (2017) 8:35326–38. 10.18632/oncotarget.15108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Gore L, Rothenberg ML, O’Bryant CL, Schultz MK, Sandler AB, Coffin D, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the oral histone deacetylase inhibitor, MS-275, in patients with refractory solid tumors and lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2008) 14:4517–25. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Kummar S, Gutierrez M, Gardner ER, Donovan E, Hwang K, Chung EJ, et al. Phase I trial of MS-275, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, administered weekly in refractory solid tumors and lymphoid malignancies. Clin Cancer Res an Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res (2007) 13:5411–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Ryan QC, Headlee D, Acharya M, Sparreboom A, Trepel JB, Ye J, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of MS-275, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, in patients with advanced and refractory solid tumors or lymphoma. J Clin Oncol (2005) 23:3912–22. 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Reiman T, Savage KJ, Crump M, Cheung MC, MacDonald D, Buckstein R, et al. A phase I study of romidepsin, gemcitabine, dexamethasone and cisplatin combination therapy in the treatment of peripheral T-cell and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; the Canadian cancer trials group LY.15 studydagger. Leukemia Lymphoma (2018) 60(4):912–9. 10.1080/10428194.2018.1515937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Siu LL, Pili R, Duran I, Messersmith WA, Chen EX, Sullivan R, et al. Phase I study of MGCD0103 given as a three-times-per-week oral dose in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol (2008) 26:1940–7. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Chan E, Chiorean EG, O’Dwyer PJ, Gabrail NY, Alcindor T, Potvin D, et al. Phase I/II study of mocetinostat in combination with gemcitabine for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer and other advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol (2018) 81:355–64. 10.1007/s00280-017-3494-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Younes A, Oki Y, Bociek RG, Kuruvilla J, Fanale M, Neelapu S, et al. Mocetinostat for relapsed classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol (2011) 12:1222–8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70265-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Batlevi CL, Crump M, Andreadis C, Rizzieri D, Assouline SE, Fox S, et al. A phase 2 study of mocetinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory lymphoma. Br J Haematol (2017) 178:434–41. 10.1111/bjh.14698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Grivas P, Mortazavi A, Picus J, Hahn NM, Milowsky MI, Hart LL, et al. Mocetinostat for patients with previously treated, locally advanced/metastatic urothelial carcinoma and inactivating alterations of acetyltransferase genes. Cancer (2019) 125:533–40. 10.1002/cncr.31817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Blum KA, Advani A, Fernandez L, Van Der Jagt R, Brandwein J, Kambhampati S, et al. Phase II study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor MGCD0103 in patients with previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol (2009) 147:507–14. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07881.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Garcia-Manero G, Assouline S, Cortes J, Estrov Z, Kantarjian H, Yang H, et al. Phase 1 study of the oral isotype specific histone deacetylase inhibitor MGCD0103 in leukemia. Blood (2008) 112:981–9. 10.1182/blood-2007-10-115873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Richardson PG, Laubach JP, Lonial S, Moreau P, Yoon SS, Hungria VT, et al. Panobinostat: a novel pan-deacetylase inhibitor for the treatment of relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther (2015) 15:737–48. 10.1586/14737140.2015.1047770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]