Abstract

Microglial/macrophage activation plays a dual role in response to brain injury after a stroke, promoting early neuroinflammation and benefit for neurovascular recovery. Therefore, the dynamics of stroke-induced cerebral microglial/macrophage activation are of substantial interest. This study used novel anti-Iba-1-targeted superparamagnetic iron–platinum (FePt) nanoparticles in conjunction with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure the spatiotemporal changes of the microglial/macrophage activation in living rat brain for four weeks post-stroke. Ischemic lesion areas were identified and measured using T2-weighted MR images. After injection of the FePt-nanoparticles, T2*-weighted MR images showed that the nanoparticles were seen solely in brain regions that coincided with areas of active microglia/macrophages detected by post-mortem immunohistochemistry. Good agreement in morphological and distributive dynamic changes was also observed between the Fe+-cells and the Iba-1+-microglia/macrophages. The spatiotemporal changes of nanoparticle detected by T2*-weighted images paralleled the changes of microglial/macrophage activation and phenotypes measured by post-mortem immunohistochemistry over the four weeks post-stroke. Maximum microglial/macrophage activation occurred seven days post-stroke for both measures, and the diminished activation found after two weeks continued to four weeks. Our results suggest that nanoparticle-enhanced MRI may constitute a novel approach for monitoring the dynamic development of neuroinflammation in living animals during the progression and treatment of stroke.

Keywords: Ischemic stroke, neuroinflammation, microglial/macrophage activation, Iba-1-antibody-conjugated superparamagnetic iron–platinum nanoparticles, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Neuroinflammation is a prominent response of the brain to cerebral ischemic stroke.1,2 Neuroinflammation in ischemic brain results from the activation of microglia, the brain-resident macrophages, and from blood-borne macrophages that infiltrate from the circulation.3–5 Microglia rapidly develop a pro-inflammatory phenotype in response to acute stroke injury; meanwhile, activation of microglia also present reparative and anti-inflammatory roles through a regulatory/homeostatic phenotype, which facilitates recovery.3,6–9 Neuroinflammation accompanies these changes in the phenotypes of the microglia/macrophages after ischemic stroke, with one phenotype predominating over another in a time-dependent manner.7,10,11 Dynamic analysis by ourselves and others have demonstrated that the location of the active microglia/macrophages with respect to the infarct in ischemic brain at different stages is a critical feature of these immune phenotypes.7,12–16 We also found that in the peri-infarct areas adjacent to intact tissue, a new population of active regulatory-phenotype microglia is involved in blood–brain barrier (BBB) remodeling at four weeks post-stroke.17 Therefore, measurement of the spatiotemporal distribution of microglial/macrophage activation in vivo would provide insight into the development of neuroinflammation after ischemic stroke. This dynamic monitoring could be helpful for treatments targeting microglia/macrophages in finding ways to suppress the deleterious effects of microglial/macrophage activation without compromising neurovascular repair and remodeling.1,18

Non-invasive monitoring of microglial/macrophage activity in living ischemic brain requires an in vivo imaging method that can specifically detect the microglia/macrophages. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has long been applied to the diagnosis and surveillance of stroke in humans and animals. However, these images do not specifically report the activation of the post-infarct microglia/macrophages. In order to accomplish this, magnetic materials targeted to a particular pathology are required to be detected in the brain with MRI. Previously, we have developed such specifically-targeted materials19,20 and have successfully used MRI, and both iron oxide-based and novel iron–platinum (FePt)-based nanoparticles, to detect and treat prostate cancer.21–23 We have also showed that antibody-conjugated, superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles could be engineered to penetrate the BBB and to serve as an in vivo contrast agent for the specific MRI detection of amyloid-β plaques in transgenic Alzheimer’s mice.24 However, until recently, the specific targeting of nanoparticles to microglia/macrophages in the ischemic brain had not been examined with MRI. We have synthesized superparamagnetic FePt nanoparticles (SIPPs) that reveal neuroinflammation through their antibody-mediated interaction with ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba-1), a 17 kDa protein specifically expressed in microglia/macrophages. Iba-1 expression by microglia/macrophages is significantly enhanced in the brain after ischemic stroke.25 We recently showed that MR imaging enhanced with Iba-1 antibody-conjugated particles could serve as a sensitive, specific means to detect and quantify the neuroinflammation associated with Alzheimer’s disease and its reduction after treatment with nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) inhibitors.26

In this study, we report the application of these unique anti-Iba-1-conjugated FePt magnetic nanoparticles to the non-invasive, MR imaging of the spatiotemporal distribution of microglial/macrophage activation in the living rat brain after stroke. The spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) subjected to middle cerebral artery occlusion with reperfusion (MCAO/RP) was used as a model of cerebral ischemia. T2w MR imaging was used to measure the anatomical location and extent of the infarcted region, while T2*-weighted (T2*w) MR imaging was employed to detect the distribution of the anti-Iba-1-conjugated FePt nanoparticle-labeled microglia/macrophages in rat brains. The MRI findings were compared with post-mortem histological analysis of the locations of the Fe+ cells and the active microglia/macrophages in the rat brains. We reconstructed the three-dimensional distribution of the activated microglia/macrophages in the whole brain using spatial measurements of the nanoparticle locations detected with T2*w MR imaging. Here, we show that the long-term and spatiotemporal MRI monitoring of the Iba-1-labeled FePt nanoparticles bound to activated microglia/macrophages correlates with neuroinflammation occurring in the living brain after an ischemic stroke.

Methods and materials

A detailed description of the methods is found in the supplemental methods.

Synthesis of FePt cores

SIPPs were synthesized according to our previously published methods.19,20,26,27

Incorporation of the FePt cores into SIPP micelles

The construction of SIPP micelles (SIPP micelles with polysorbate 80 (SM80s)) was based on a thin-film hydration process followed by extrusion through a controlled pore membrane. The composition of the SM80s is given in supplementary Table 1. We used a polyethyleneglycol coating to evade the reticuloendothelial system and to avoid the buildup of a protein corona.8 This procedure made ∼4.6 × 1014 SIPP micelles containing ∼6 × 104 dipalmitoyl-sn-glycerolphosphorylcholine molecules/micelle with ∼98 biotin sites/micelle.

Protein conjugation to the SIPP micelles

Proteins (anti-Iba-1 and ApoE2) were streptavidinated using Lightning-Link Streptavidin conjugation kits from Innova Biosciences according to the manufacturer’s protocol (www.novusbio.com/lightning-link-conjugation-kits). The modified proteins were then combined and added to the biotinylated micelles to produce the finished SM80s at an iron concentration of 12.5 mg/mL.26

Rat model of MCAO with RP and timeline for injections

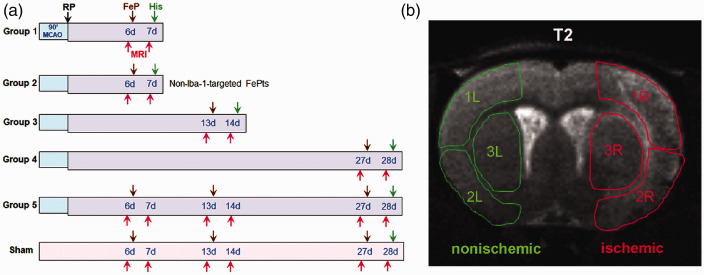

This study was approved by the University of New Mexico Animal Care Committee and conforms to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for use of animals in research. Every effort was made to minimize the number of experimental animals used and their suffering. Reporting of this work complies with ARRIVE guidelines.28 Male SHRs (12 weeks old) were subjected to 90 min MCAO followed by RP for one, two, and four weeks as previously described;17,29 100 µl of the anti-Iba-1-conjugated SM80s or control SM80s lacking the anti-Iba-1 antibody (containing 1.25 mg Fe, giving an iron dose of ∼5 mg/kg) were intravenously injected via the tail vein and the rats were imaged 24 h later using T2w and T2*w MR sequences according to the scheme shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of the rat experimental groups and regions of interest (ROI) used for MRI image intensity measurements. (a) An outline of the experimental protocol showing the timing of the MRI scans, the injections of the SM80s, and the post-mortem histological analysis at various reperfusion (RP) times after MCAO. Groups 1, 3, and 4 received one injection of Iba-1-targeted SM80s (Iba-1-SM80s) and one MRI scan at one, two, and four weeks, respectively. Group 5 received three injections of Iba-1-targeted SM80s and three MRI scans at one, two, and four weeks. Group 2 received one injection of non-Iba-1-targeted, control SM80s (SM80s) and one MRI scan at one week Sham rats received three injections of Iba-1-SM80s and three MRI scans at one, two, and four weeks. The time of various procedures is indicated as MCAO: a 90 min middle cerebral artery occlusion; RP (↓): the time at which reperfusion was begun. FePt (↓): nanoparticle injection time-point. MRI (↓): MRI scan time-point. His (↓): post-mortem histological analysis time-point. (b) A representative slice from T2-weighted image of a Group 1 rat brain taken seven days after MCAO/RP showing the ROIs used for the measurement of the signal intensities in the ipsilateral and contralateral portions of the brain. Within each hemisphere, three regions, including the cortex (1, 2) and striatum (3), were measured. MCAO was performed on the right hemisphere (R, ischemic), while the left hemisphere served as a nonischemic (L, nonischemic) control region. Note the hyperintensity of the right cortex compared with the left due to edema.

The following groups of SH rats were used (Figure 1(a)): Group 1 (n = 11) rats subjected to the MCAO and injected with anti-Iba-1-conjugated SM80 nanoparticles (Iba-1-SM80s) six days later which were imaged prior to and 24 h post-injection; Group 2 (n = 10) rats subjected to the MCAO and injected with control, non-anti-Iba-1-conjugated SM80s (SM80s) six days later which were imaged prior to and 24 h post-injection; Group 3 (n = 9) rats subjected to the MCAO and injected with Iba-1-SM80s 13 days later which were imaged prior to and 24 h post-injection; Group 4 (n = 10) rats subjected to the MCAO and injected with Iba-1-SM80s 27 days later which were imaged prior to and 24 h post-injection; and Group 5 (n = 9) rats subjected to the MCAO and injected with Iba-1-SM80s 6, 13 and 27 days later which were imaged prior to and 24 h post-injection. Sham group (n = 6) rats, as non-ischemic injury control, injected at one, two, and four weeks with Iba-1-SM80s which were imaged prior to and 24 h after each injection. A total of 57 SHRs were used, including two rats which died at day12 (Group 3) and day 17 (Group 5) after RP during the long-term studies.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI was performed at a 4.7 T Bruker BioSpec 47/40 USR magnet system (Billerica, MA) equipped with Avance III electronics.17,30–32 T2 measurements and T2w images were taken with 12 1-mm-thick slices for each rat brain. Gradient-echo T2*w images and T2* measurements were obtained from 16 slices of 0.5 mm each brain. Both T2w and T2*w images were located at rat brain planes within Bregma ∼ +2.00 to –7.80 mm.33

MRI data analysis

The infarct from the MCAO was confined to the right side of the brain and three regions of interest were defined for the ventral and dorsal cortex and the striatum on both the left (L, nonischemic) and right (R, ischemic) hemisphere of the brain (Figure 1(b)). The image intensities (R, L) in the T2w and T2*w MR images were measured with the aid of ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/index.html) for 350–500 pixels in each of these six regions and used to compute the Right/Left contrast, Cp, prior to the injection of the SM80s; as Cp = (Ri – Li)/Li, i ∈ {1,2,3}. The R/L contrast after (Ca) injection was similarly defined as Ca = (Rj – Lj)/Lj, j ∈ {1,2,3}. The resulting contrast difference is ΔC = Ca – Cp. Since the nanoparticle-bound microglia appeared as punctate, hypointense regions in the post-injection T2*w MR images as a result of the reduction in the T2* value of the microglia-associated water in the tissue,20 the contrast difference (ΔC) was found to be negative for tissues that had taken up the nanoparticles. Indicators of animal group identity on images were blinded to the investigators.

We observed and corrected for an asymmetry of the intensity between the right and left brain regions, even in control (sham) rat images due to the inherent radiofrequency inhomogeneity of the surface coil used to obtain the images (supplementary Figure 1). We measured this intensity ratio r = IR/IL in the sham rat brains as r = 1.20 (n = 6) and used it to correct the left-sided image intensities prior to contrast calculations.

Z-scores (contrast to noise ratios) of the punctate hypointensities were computed using measurements of the minimum, M(x, y, z), of the MR signal at its x, y, and z coordinates (z is the slice position) as previously described.24

Immunohistology

Perl’s Prussian Blue and counter staining for detecting Fe+-cells were performed on 10 µm formalin-fixed brain sections by Tricore Reference Laboratory (Albuquerque, NM). For immunohistochemistry (IHC), brain sections were stained using anti-Iba-1, anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), anti-interleukin 1beta (IL)-1β, anti-interleukin 10 (IL)-10, anti-transforming growth factor-beta (TGF)-β, anti-YM1, and anti-OX-42 (CD 11 b).

Quantification of Iba-1 fluorescence intensity and counting of Fe+-cells

The mean staining intensity of the Iba-1 immunofluorescence was measured using ImageJ (NIH) in sections of ischemic hemispheres and used to quantify the activation of microglia/macrophages as described in our previous study.17 The number of Fe+-cells in Perl’s Prussian Blue-stained images of the ischemic hemispheres was counted using the ImageJ “cell_counter.jar” plug-in. Indicators of animal identity on slides were blinded to the investigators.

Quantification for colocalization of cytokines with Iba-1

Analysis and quantification of cytokines expressed in Iba-1-positive microglia/macrophages were performed using the colocalization plugin Coloc2 in Fiji-ImageJ as described in our previous report.17 Li’s intensity correlation quotient (ICQ) value, which provides an overall index of colocalization, is distributed between –0.5 and +0.5. Random staining produces a value of the ICQ ∼ 0, while segregated staining gives a negative value (0 > ICQ > –0.5) and co-localized staining produces a value of 0 < ICQ ≤ +0.534,35 (supplementary Figure 3). Indicators of animal identity on slides were blinded to the investigator.

Statistics

Unpaired t-tests or one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) were performed for two groups or for multiple group comparisons (with a post-hoc Student–Newman–Keuls test), respectively. Two-way (−factors) ANOVA were performed for group comparisons with time course analysis. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to calculate the correlation coefficients between the T2*w ΔC values and the mean staining density values of Iba-1 immunofluorescence. In all statistical tests, differences were considered significant when P < 0.05. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism, version 6.0 (GraphPad Software Incorporated).

Results

T2*w MR images and histology one week after MCAO/RP showed the Iba-1-conjugated SM80s only in the infarcted region

We first determined that one week after MCAO/RP, the anti-Iba-1-conjugated SM80s (Iba-1-SM80s), penetrated the BBB, bound to Iba-1+-microglia/macrophages, and produced hypointensities in the T2*w MR images of living rat brains (Figure 2). The initial time point at one week was chosen based on studies by ourselves and others showing that activated microglia were observed mainly in the regions within the infarct and peri-infarct areas between two and seven days after transient ischemia,36,37 and these reached a peak at one week that persisted to four weeks.17 To exclude any potential interference from susceptibility variations in the MR images from iron in hemorrhages, animals were imaged twice using a T2*w MR sequence: the first scan was performed prior to nanoparticle injection (vide supra), while the second MR image set was obtained 24 h after the injection of nanoparticles. The data from the first scan were used as a baseline to compensate for any hemorrhage-related susceptibility variations.

Figure 2.

Active microglia shown by MRI and histological analysis in the brain of a rat (Group 1) at one week after MCAO/RP. (a) MR T2w and T2*w images taken before (pre-injection) of Iba1-SM80s. The anatomic T2w image shows the lesion as a right-sided hyperintense region. A T2*w gradient-recalled echo image of the same slice. (b) MR T2w and T2*w images taken 24 h post-injection (after-injection) of Iba1-SM80s. A T2w image of the brain of this rat showing the same right-sided hyperintense region. A T2*w image showing the location of the magnetic nanoparticles as punctate hypointensities. (c) Intensity profile of the T2*w MR image from (b) (right) taken along the indicated white line in the T2*w post-injection image. Note that the intensity is lower in the ischemic hemisphere (arrow) compared to the nonischemic one. (d) A post-mortem formalin-fixed brain slice from the same rat shows that the lesion area in the ischemic hemisphere (arrow) coincides with that seen in the T2w image in (a) (left). (e) A brain section immunofluorescently stained for Iba-1 (green) shows that the distribution of active microglia in the ischemic hemisphere of this brain matched the areas of hyperintensity seen in the T2w image (a) (left). (f) The distribution of Fe+-microglia determined using Perl’s Prussian Blue staining in the non-ischemic hemisphere and in the ischemic hemisphere of the same brain as in (a). Note that Fe+-microglia only appear in the brain tissue from the ischemic region. Scale bars = 100 µm.

CTX: cortex; Str: striatum; V: vessel.

Prior to injection of the nanoparticles, T2w and T2*w MR images of the infarcted region of the brain displayed a typical pattern of hyperintensities due to cerebral cytotoxic edema in the ischemic hemisphere compared to the nonischemic hemisphere (Figure 2(a)). This edema lead to an increase of the T2 and T2* values in the involved tissues. This background pattern of T2w MR image hyperintensities continued to be observed in the T2w images after the injection of the Iba-1-SM80s (Figure 2(b), left panel). The post-injection T2*w MR images, however, showed prominent, punctate hypointensities in the ischemic hemisphere, suggesting that the injected Iba-1-SM80s were bound to the activated microglia/macrophages clustered within the infarcted region (Figure 2(b), right panel). The nanoparticle-bound microglia/macrophages in the ischemic hemisphere appeared as hypointense regions as a result of the reduction in the T2* value (Figure 2(c)) of the iron bound microglial-associated water relative to the surrounding tissue and nonischemic hemisphere. These T2*w hypointensities were absent both from the pre-injection images and from the nonischemic hemisphere. The hyperintense regions in the T2w MR images or the hypointense regions in the T2*w images corresponded to the lesion regions shown in the post-mortem perfusion-fixed brain (Figure 2(d)) and the regions of immunohistochemical staining for activated microglia/macrophages using anti-Iba-1 antibody (Figure 2(e)) in the same rat. Our data demonstrated that the distribution and intensity of the Iba-1-SM80s shown by T2*w MR imaging in living rat brains were consistent with those of microglia/macrophages labeled by Iba-1 IHC staining on the brain sections.

Perl’s Prussian Blue staining of the post-mortem perfused brain sections was utilized to confirm the specific distribution of Fe from the Iba-1-SM80s seen as prominent hypointense regions in the T2*w MR images in the ischemic hemisphere (Figure 2(f)). The histological staining showed that the Fe+-cells were only observed in the lesion areas of the ischemic hemisphere. The Perl’s Prussian Blue stains revealed that the Iba-1-SM80s were bound to and taken up by cells in locations where the infarct and the Iba-1-SM80s were detected in the T2*w images (Figure 2(b)). Fe+-cells were also seen around vessels in the peri-infarct areas (Figure 2(f), right panel), indicating that they indeed crossed the BBB.

The specificity of the Iba-1-SM80s was conferred by the anti-Iba-1 antibodies

To show that the specificity of the Iba-1-SM80s was determined by the presence of the surface anti-Iba-1 antibodies, we also prepared control SM80s (denoted simply as SM800) that lacked the anti-Iba-1 antibodies, but were identical in all other components. A group (group 2; Figure 1(a)) of MCAO/RP SH rats was injected at day 6 with these control SM80s and imaged at day 7 at the presumed peak of Iba-1-positive microglial/macrophage activation.17 A comparison of T2w images (Figure 3(a), right) from the brains of rats injected with these control SM80s with those from the brains of rats at seven days after MCAO/RP and injected with the full Iba-1-targeted SM80s (Figure 3(a), left) showed that, although the infarcts were of similar size in these two groups of rats, significant hypointense regions in the T2*w MR images were only detected in the ischemic hemisphere from the rats injected with the Iba-1-SM80s; these were not seen in the images of the brains of rats injected with control SM80s. T2*w image hypointensities were not seen in the infarcted region either prior to (Figure 3(a), middle-right) or after (Figure 3(a), bottom-right), the injection of the control SM80s, whereas injection of the full, anti-Iba-1-conjugated SM80s produced image changes similar to those presented in Figure 2(b).

Figure 3.

MR imaging and histological analysis show that Iba1-SM80s produce specific imaging changes compared with control, non-Iba1-targeted-SM80s (SM80s) in ischemic hemispheres at one week after MCAO/RP. (a) T2w and T2*w MR images of the brains from rats injected with either Iba1-SM80s (Group 1) or SM80s (Group 2). T2w images (top row) show that the spatial extant and size of the cortical and striatal edema in the infarcted regions was similar in both groups. The arrow indicates the ischemic hemisphere. The pre-injection T2*w MR images (middle row) show a smooth cortex and striatum. The post-injection T2*w MR images (bottom row) show the SM80s as punctate hypointense regions in only the image from the rat injected with Iba1-SM80s (bottom, left), while no such effect is seen when control SM80s were used (bottom, right). (b) The effect of magnetic nanoparticle injection on the quantitative contrast of the T2*w MR images in rat brains obtained pre- and after nanoparticle injections. The intensities of the three lesion regions of interest (in the ischemic hemisphere) and those of the three contralateral of interest (in the nonischemic hemisphere) (see Figure 1(b)) were measured and used to compute the Right (R)/Left (L) contrast as C = (Ri – Li)/Li, i ∈ {1,2,3}. This contrast decreased significantly (p = 0.001) after the injection of the Iba1-SM80s (b, left), while no significant contrast change was observed after the injection of the control SM80s (b, right; p = 0.16). (c) Contrast (Ca) of T2*w MR image obtained after injections with either Iba1-SM80s or SM80s. There was a significant difference (p = 0.02) in contrast obtained after injection of the Iba1-SM80s compared with the control SM80s. (d) Quantitative contrast changes (ΔC) between T2*w MR images obtained in rat brains before (Cp) and after-injection (Ca) with either Iba1-SM80s or control SM80s. Sham rats were injected with Iba1-SM80s and there was no contrast change, ΔC = 0.009. The brains from Group 1 rats injected with Iba1-SM80s showed a significantly different negative contrast change of ΔC = –0.087. Injection of control SM80s into rats produced only a slightly negative ΔC = –0.036. n = 6 rats in the sham group, n = 11 in the Iba1-SM80s group, and n = 10 in the control SM80s group. (e) Perl’s Prussian Blue staining for Fe+-microglial cells in the rat brains injected with control SM80s. No Fe+-cells were seen in the cortex (CTX), while only a few were observed in the area of the striatum (Str) in the ischemic hemisphere. Scale bars = 50 µm.

**p < 0.01 vs. sham and SM80s groups.

#p < 0.05 vs. sham group.

Quantitative contrast measurements based on the T2*w MR images showed that injection of Iba-1-SM80s significantly reduced the L/R contrast (Ca) compared to the contrast (Cp) before injection of the Iba-1SM80s (Figure 3(b), left). No such significant change in contrast was observed when the control SM80s were used (Figure 3(b), right). This result was also supported by the data shown in supplementary Figure 4 where the T2*w image intensities between nonischemic and ischemic hemispheres were compared. Comparison of the post-injection contrast values (Ca) between the Iba-1-SM80s and the control SM80s (Figure 3(c)) gave additional support for this result.

Furthermore, we measured the contrast change (ΔC = Ca – Cp) in T2*w MR images (Figure 3(d)). The mean of the T2*w contrast change was essentially zero (ΔC = +0.009) in the sham rats injected with the Iba-1-SM80s at one week, indicating a lack of uptake of the Iba-1-SM80s. Injection of the Iba-1-SM80s into rats seven days after MCAO/RP resulted in a robust mean negative contrast change of ΔC = –0.087, suggesting significant uptake of the Iba-1-SM80s in the infarcted region compared to the sham rats (p = 0.0011). Significant uptake of the control SM80s (ΔC = –0.036) in the infarcted region seven days after MCAO/RP was detected compared to the sham rats (p = 0.0164), reflecting some non-specific phagocytosis of the control SM80s by active microglia/macrophage and reactive astrocytes in the peri-infarct areas.38 However, the uptake of the control SM80s was significantly lower than that of Iba-1-SM80s in the infarcted region (p = 0.0099). Accordingly, the injection of control SM80s resulted in a few Fe+-cells in the ischemic hemisphere (Figure 3(e)), which differed markedly from the strong Perl staining seen in the brain injected with Iba-1-SM80s at one week after MCAO/RP (Figure 2(f)).

Longitudinal MRI after multiple injections of Iba-1-SM80s showed that they did not accumulate in the brain tissue

To determine whether the FePt nanoparticles accumulated in the brain over time, we imaged groups of rats (including sham rats) that received injections of Iba-1-SM80s at one, two, and four weeks (for a total of three injections) and compared the results with rats that received single injections of Iba-1-SM80s at either one, two, or four weeks, respectively. T2w and T2*w MR images of the brains in sham rats obtained after injections of Iba1-SM80s at one, two, and four weeks showed an absence of both edema and image hypointensities (Figure 4(a)). On the other hand, we observed numerous punctate hypointensities in the T2*w images obtained after the injection of Iba1-SM80s which peaked one week after MCAO/RP, and diminished from two to four weeks after MCAO/RP, and mostly surrounded the core infarct areas (Figure 4(b)). This result was also congruent with imaging performed on animals which received only a single injection of Iba1-SM80s at one, two, or four weeks, respectively, where significant T2*w hypointensities were only observed at the one week (Figure 4(c), upper right). These results indicated that the nanoparticles did not accumulate in the tissue over the course of this study. Furthermore, post-mortem Perl’s Prussian Blue staining of the brains from rats that received three injections of Iba1-SM80s showed no Fe+-cells in sham brain, while only a slight residuum of Perl’s Fe+ cells were seen in the peri-infarct areas in the striatum in the fourth week MCAO/RP brain (Figure 4(d)).

Figure 4.

A comparison of MR images obtained after single vs. multiple injections of the Iba-1-SM80s shows that image intensity perturbations decay within a few days so that the nanoparticles did not accumulate in the brain tissue. (a) T2w and T2*w MR images of the sham rat brains obtained 24 h after the injection of Iba1-SM80s at one, two, and four weeks (W). These animals received three injections of Iba1-SM80s. (b) T2w and T2*w MR images of the brains of Group 5 rats obtained 24 h after the injection of Iba1-SM80s at one, two, and four weeks after MCAO/RP. These animals received three injections of Iba1-SM80s. Substantial punctate hypointensities in the T2*w images were found in the whole ischemic area at one week, which were also seen in the regions surrounding the core infarct areas (bright high intensity) at two and four weeks. (c) T2w and T2*w MR images obtained 24 h after-injection of Iba1-SM80s into rats at one week (Group 1), two weeks (Group 3), and four weeks (Group 4) after MCAO/RP. These animals received single injection of Iba1-SM80s at one, two, and four weeks, respectively. Here, the hypointensities in the T2*w images were similar to that observed in (b). (d) Perl’s Prussian Blue staining for Fe+-microglia in the sham or in the MCAO/RP rats from (a) and (b) at four weeks, after receiving three injections. Photos were taken from the cortex (CTX) and striatum (Str) areas shown as arrowheads in (a) and (b). Scale bars = 100 µm. Note the lack of significant blue staining in the tissue from sham rats, which is in contrast to the residual blue staining seen in the fourth week MCAP/RP group. (e) Quantitative contrast (Ca) in the T2w MR images of the rat brains taken 24 h after either single or multiple injections of Iba-1-SM80s at one, two, and four weeks after MCAO/RP. m: multiple-injection groups (sham group and Group 5); s: single-injection groups (Groups 1, 3, and 4). *p < 0.01 vs. 1-injection MCAO/RP groups at one week (1 W), ***p < 0.001 vs. 1-injection and 2-injecton MCAO/RP groups at two weeks (2 W), ****p < 0.0001 vs. 1-injection and 3-injection MCAO/RP groups at four weeks (4 W). (f) Comparison of the contrast changes (ΔC = Ca – Cp) of T2*w MR images between rats with three serial injections and rats with a single injection, at one, two, and four weeks after MCAO/RP. **p < 0.01 vs. 1-injection MCAO/RP group at one week, *p < 0.05 vs. 1-injection and 2-injecton MCAO/RP groups at two weeks. n = 6 in 3-injection sham group; n = 11, 9, and 10 in 1-injection MCAO/RP groups; n = 8 in 3-injection MCAO/RP group.

In order to place these qualitative results onto a quantitative basis, we measured the T2w image contrast Ca (Figure 4(e)) and T2*w MR image contrast change ΔC (Figure 4(f)) at one, two, and four weeks after either single or multiple injections of Iba1-SM80s into groups of sham and MCAO/RP rats. Compared with sham rat brains, T2w image contrast measurements showed significant increase of the Ca values in ischemic rat brains receiving either single (s) or multiple (m) injections of Iba1-SM80s at all three time points, due to the continued development of edema in infarcted regions (Figure 4(e)). There were no significant contrast differences between single and multiple injection groups at any time point. Measurements of the contrast differences (ΔC = Ca – Cp) from the T2*w MR images showed no difference in contrast changes (ΔC = 0) in the brains of sham rats injected with Iba1-SM80s for any point from one to four weeks, independent of the number of injections (Figure 4(f)). Negative ΔC values were detected in the MCAO/RP group of rats at all time points investigated, while significant negative ΔC values were observed compared to sham rats independent of the number of injections at one and two weeks. In addition, we also measured the post injection contrast (Ca) in T2*w images and found that a significant difference of the Ca was only seen when sham and one-week MCAO/RP groups were compared (supplementary Figure 5). Importantly, the results show that single or multiple injections produced the same T2w contrast (Ca), T2*w contrast (Ca), and T2*w contrast changes (ΔC), at each time point.

Longitudinal monitoring of microglial activation after MCAO/RP with Iba1-SM80-enhanced MR imaging and IHC

To determine the longitudinal time-course of stroke-induced inflammation after ischemia and to map the specific changes in microglial/macrophage activation, we further compared the Iba-1-SM80s distribution measured from T2*w MR images with those from the histological analyses for Iba-1+-microglia/macrophages at one, two, and four weeks after MCAO/RP. T2*w MR images of the rat brains 24 h after single Iba-1-SM80 injections into either sham or MCAO/RP rats showed the locations of the SM80s as punctate, hypointense areas in the infarct and peri-infarct regions (Figure 5(a)). After the MR images were obtained, the rats were sacrificed and the brains were sectioned for histological studies. The regions of microglial/macrophage activation revealed by Iba-1 antibody staining (Figure 5(a), right) closely coincided with the regions of edema and Iba-1-SM80 uptake in the T2w* MR images (Figure 5(a), left) at all three time points. No hypointense areas and activated microglia/macrophages were observed in sham rat brains. The results from both imaging techniques indicated that the activation of the microglia/macrophages in response to MCAO/RP peaked at one week, and then diminished significantly from two to four weeks when activated microglia/macrophages were only seen in the peri-infarct areas. The same time course of changes was found when comparing the densities of Perl’s stained (Fe+) cells and Iba-1+-microglia/macrophages in the same rat brain tissues (Figure 5(b)). Various morphological shapes of Fe+-cells and Iba-1+-microglia/macrophages were seen at different time points (Figure 5(b), inserts). At one to two weeks, the vast majority of Fe+-cells and Iba-1+-microglia/macrophages in the adjacent brain sections were round in shape in the core infarct areas, while both the Fe+-cells and Iba-1+-microglia/macrophages with extending processes appeared in the peri-infarct areas by four weeks. This observation suggests that the Fe+-cells are active microglia/macrophages that bound with Iba-1-SM80s. Quantitative correlation analysis showed that a strong linear relationship existed between the number of Fe+-cell and Iba1 fluorescence intensity (supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Longitudinal monitoring of microglial activation with T2w and T2*w MR imaging and immunohistochemistry. (a) The changes of the distribution of the hypointense regions in the T2*w images reflected the distribution of active microglia/macrophages by Iba-1 staining in the same ischemic hemispheres over four weeks after MCAO/RP. The left column of T2*w MR images shows the appearance of the rat brain 24 h after Iba-1-SM80 injections in sham rats and rats subjected to MCAO/RP for one, two, and four weeks. In the right column, the brains from the same animals were removed after MRI and stained for Iba-1 to reveal the location and density of activated microglia. (b) Iba-1 and Perl’s Prussian Blue staining on adjacent sections of each rat from (a). The changes of morphology and density of Fe+-cells in the ischemic hemispheres reflected the changes of active microglia/macrophages stained by Iba-1. Note that the marked right-sided edema-related hyperintensities in the T2*w images at two and four weeks were observed by histology as fluid-filled voids, due to cell death and tissue atrophy in the core infarcts. Scale bar = 50 µm. The inserts show higher magnification views of the microglia/macrophages stained for Iba-1 and Perl’s Prussian Blue. (c) The time dependence of the quantitative contrast (Ca) and contrast change (ΔC) in T2w MR images from sham or MCAO/RP rat brains following both single and three injections of Iba1-SM80s at weeks 1, 2, and 4 after MCAO/RP. Left: The T2w contrast after injection (Ca) in the MCAO/RP groups was significantly increased compared to the sham group at all time points due to edema formation. There was no significant difference of T2w Ca values between the Iba-1-SM80s rats and the control SM80s rats at one week. *p < 0.05 vs. 1 W/RP of rats with Iba1-SM80s or control SM80s; ****p < 0.0001 vs. 2 W and 4 W of sham rats. Right: The contrast change values (ΔC = Ca – Cp) showed no significant difference between the MCAO/RP groups and the sham rats at one, two, and four weeks, suggesting that the nanoparticle injection did not interfere the edema-related hyperintensities in T2w images. (d) The time dependence of the quantitative contrast (Ca) and the contrast changes (ΔC) in T2*w MR images obtained from sham or MCAO/RP rats following both single and three injections of Iba1-SM80s at weeks 1, 2, and 4 after MCAO/RP. Left: The quantitative contrast (Ca) measured in T2*w MR images was independent of time for the sham rats. A significant difference was seen in the 1 W/RP group injected with Iba1-SM80s compared to the sham, control SM80s, 2 and 4 weeks MCAO/RP groups. *p < 0.05 vs. 1 W of sham and 1 W/RP of control SM80s groups, ##p < 0.01 vs. 2 W/RP and 4 W/RP of rats with Iba1-SM80s. Injection of control SM80s at one week did not produce significant different contrast from the sham group. Right: The most significantly negative ΔC value was seen in the T2*w images at one week for the MCAO/RP rats injected with Iba1-SM80s; this value decreased at two and four weeks. ***p < 0.001 and **p < 0.01 vs. MCAO/RP groups at one week or two weeks. #p < 0.05 vs. sham group. ##p <0.01 vs. control SM80s group. n = 6 in sham group; n = 19 in MCAO/RP group at one week; n = 17 in MCAO/RP group at two weeks; n = 18 in MCAO/RP group at four week; and n = 10 in control SM80s group at one week. (e) Quantification of Iba-1 fluorescence (FL) intensity in the ischemic hemispheres at weeks 1, 2, and 4 after MCAO/RP. ****p < 0.0001 vs. vs. sham and 4 W/RP groups; ***p, 0.001 vs. sham group; *p < 0.05 vs. 1 W/RP group. n = 4 in sham group; n = 6 in MCAO/RP groups at one, two, and four weeks. (f) The number of Fe+-cells in the ischemic hemispheres at weeks 1, 2, and 4 after MCAO/RP. ****p < 0.0001 vs. sham group; ***p < 0.001 vs. 4 W/RP group; and *p < 0.05 vs. 2 W/RP group; #p < 0.05 vs. sham group. n = 4 in sham group; n = 6 in MCAO/RP groups at one, two, and four weeks. (g) Pearson’s correlation between the T2*w ΔC values and the mean density of Iba-1 immunofluorescence for the various time points. Correlations: R2 = 0.4213, p = 0.1556, in the sham group; R2 = 0.6344, p = 0.0025, in the 1 W/RP group; R2 = 0.8112, p = 0.0028, in the 2 W/RP group; R2 = 0.0255, p = 0.2465, in the 4 W/RP group. n = 4 in sham group; n = 6 in MCAO/RP groups at one, two, and four weeks.

Since no differences were detected in the T2w and T2*w MR contrast data between single and multiple nanoparticle injections (Figure 4 and supplementary Figure 6), we combined the MRI contrast data from both the single and the multiple injection groups at each time point to determine the longitudinal time-course of stroke-induced inflammatory changes. The marked hyperintensities observed in T2w MR images in the MCAO/RP rat groups (Figure 4(b) and (c)) reflected edema formation in the ischemic hemispheres after MCAO/RP. Measurements of T2w MR image contrast (Ca) demonstrated the development of edema over the four weeks after MCAO/RP compared with sham rats (Figure 5(c), left). However, no significant contrast differences (ΔC) were found in T2w images (Figure 5(c), right), because the edema was the same both before and after the injection of the Iba-1-SM80s, and this hyperintense background subtracted out.

Because the measured r2* MR relaxivity of SM80s (853 Hz/mM) was almost three-fold greater than their r2 relaxivity (300 Hz/mM),20 we expected that T2*w MR images would show the largest effect of the nanoparticles. T2*w MR image contrast (Ca), and contrast changes (ΔC) reflected the time-dependent presence of the Iba-1-SM80s (Figure 5(d)) with the maximum effect observed at one week post-stroke. Both of these measures of neuroinflammation diminished with time from week 1 to week 4, due to the decreased specific binding of Iba-1-SM80s, in concert with the observed decrease of the Iba-1+-microglia/macrophages over time after MCAO/RP (Figure 5(b)). However, significant negative ΔC values were observed at both one and two weeks compared to sham rats (Figure 5(d), right), while significant negative Ca values were only detected at one week (Figure 5(d), left). Clearly, the T2*w MRI contrast change (ΔC) was the most sensitive of the MRI measures of the time-dependent changes of microglial/macrophage activation, while the T2*w ΔC values for the sham rats were zero for all time points (Figure 5(d), right).

We next measured the Iba-1 fluorescent intensity and the number of Fe+-cells stained with Perl’s Prussian Blue in the ischemic hemisphere. Significant increases of Iba-1 fluorescence intensity (FL) (Figure 5(e)) and Fe+-cell number (Figure 5(f)) were detected at week 1 and 2 groups, but not at week 4, compared with the sham rats. The dynamics of Iba-1 fluorescence intensity and Perl’s staining closely followed the time-dependent changes of the T2*w ΔC values (Figure 5(d), right). Finally, the correlation coefficients between the T2*w ΔC measurements and the mean Iba-1 fluorescence intensity values for each rat was examined using Pearson correlation analysis (Figure 5(g)). The T2*w ΔC values were significantly correlated with the Iba-1 fluorescent intensity values at both week 1 (R2 = 0.6344, p = 0.0025) and week 2 (R2 = 0.8112, p = 0.0028), but not at week 4. These results paralleled the time-dependent changes of the T2*w ΔC values (Figure 5(d), right).

Three-dimensional mapping of the SM80s within the brain parenchyma

MR images are quantitative maps of these tissue relaxation characteristics in three-dimensions. We used the T2*w MR images to generate 3 D maps of the distribution of the activated microglia/macrophages. A representative set of T2*w MR images from a rat brain at one week after MCAO/RP displayed the punctate regions of hypointensity (Figure 6(a)) in the ischemic hemisphere, indicating that the Iba-1-SM80s bound exclusively to the activated microglia/macrophages. Measurements of the positions and Z-scores of the hypointense voxels were used to generate a three-dimensional map of the Iba-1-SM80s, and hence the activated microglia/macrophages in the post-MCAO brain (Figure 6(b)). The results showed that the magnetic nanoparticles were found only within the brain area affected by the ischemic intervention located in the brain regions from ∼ +1.70 to –7.64 mm with respect to the Bregma.

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional (3D) mapping of the Iba-1-SM80s within the brain parenchyma (a). T2*w MR images of the brain of a Group 1 rat injected with Iba-1-SM80s seven days after MCAO/RP. The arrows show the ischemia produced by MCAO. Images were obtained from sixteen slices whose locations in the brain ranged from ∼ Bregma +1.70 to –7.64 mm. (b) The Z-score distribution of the Iba1-SM80s in three-dimensions within the brain where the location corresponded to the punctate regions of low signal intensity and the radius and color of the plotted spheres corresponded to the Z-score (See Supplementary Methods for details of the mapping used in Mathematica). Shown are three different views of the same data set, but individually rotated for clarity. Note that the Iba1-SM80s cluster in the region of the infarct and nowhere else within the brain.

Changes of expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the active microglia/macrophages from one to four weeks after MCAO/RP

To correlate the changes of distribution of the SM80s in ischemic rat brains observed by T2*w MRI with the time-dependence of the switch of the microglial/macrophage immunophenotype from its pro- to its anti-inflammatory state, we performed double-IHC after MRI to detect the expression of pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines in Iba-1+- or OX-42 (CD11b)+-microglia/macrophages in ischemic brains. We first examined the expression of YM1, a marker of regulatory/anti-inflammatory microglia/macrophages, in OX-42+-microglia/macrophages. Around the border of infarct core and in the peri-infarct areas where the nanoparticles were detected by T2*w imaging, we found increasing expression of YM1 in microglia from one to four weeks after MCAO/RP (Figure 7(a), left). The Li’s ICQ value used to quantify the colocalization of YM1 and OX-42 showed significant increase of the co-localization at two and four weeks after MCAO/RP, compared to sham rats, suggesting that shifting of the microglial/macrophage activation from the pro-inflammatory to the anti-inflammatory state occurred during two and four weeks after MCAO/RP (Figure 7(a), right). We next examined the expression of four cytokines in the microglia/macrophages within the areas bordering the infarct and peri-infarct regions (no tissues exist in the core infarct area at two and four weeks after MCAO/RP, Figure 5(a)). The pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β were expressed by pro-inflammatory microglia/macrophages, and anti-inflammatory cytokines TGF-β and IL-10 were expressed by regulatory-activated microglia/macrophages.1,3,7,10,11,39–42 Compared to sham brains, significantly increased expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in active microglia/macrophages was found one to two weeks after MCAO/RP (Figure 7(b)). Decreased expression of TNF-α was seen from week 2, which reached a significant reduction at week 4 compared to week 1 (Figure 7(b), upper). A slight decrease of IL-1β expression was seen in microglia at two to four weeks (Figure 7(b), bottom), but double-IHC staining showed that most of the IL-1β was expressed by the microglia located around the border of infarct core. On the other hand, significantly increased expression of TGF-β and IL-10, the anti-inflammatory cytokines, was seen at weeks 2 to week 4, compared to the sham and 1-week MCAO/RP groups (Figure 7(c)). These results were temporally and spatially consistent with the changes of YM1 expression in active microglia in response to stroke-induced brain injury.

Figure 7.

Inflammatory cytokines expressed by active microglia/macrophage in the infarct (inf) areas bordering with the peri-infarct (peri-inf) areas at one, two, and four weeks (W) after stroke and reperfusion. (a) Double immunostaining shows the expression of YM1 in active microglia (OX-42). DAPI was used to show the nuclei. Scale bar = 50 μm. Statistical Li’s ICQ values for colocalization of YM1 with OX-42 in sham and ischemic hemispheres. *p < 0.05 vs. two weeks, **p < 0.01 vs four weeks. (b) Double immunostaining shows expression of TNF-α and IL-1β in active microglia (Iba-1). Statistical Li’s ICQ values demonstrate the quantification of colocalization of TNF-α and IL-1β with Iba-1 in sham and ischemic hemispheres. TNF-α: **p < 0.05 vs. two weeks, ****p < 0.0001 vs. one week, ***p < 0.001 vs. one week. IL-1β: **p < 0.01 vs. two and four weeks, ***p < 0.001 vs. one week. (c) Double immunostaining shows expression of TGF-β and IL-10 in active microglia (Iba-1). Statistical Li’s ICQ values demonstrate the quantification of colocalization of TGF-β and IL-10 with Iba-1 in sham and ischemic hemispheres. TGF-β: **p < 0.01 vs. two week, ***p < 0.001 vs. four weeks; ##p < 0.01 vs. two weeks, ### p < 0.001 vs. 4 weeks. IL-10: *P <0.05 vs. 2 and 4 weeks, ***p <0.001 vs. two and four weeks. n = 3 in sham groups, n = 6 in groups of one, two, four weeks reperfusion (RP).

Discussion

We demonstrated that MRI, enhanced with anti-Iba-1-conjugated FePt nanoparticles, was able to reveal the spatial distribution and longitudinal time-course of stroke-induced inflammation and to reveal the specific, localized changes in microglial/macrophage activation. A comparison of the post-mortem histological data with the location of lesion areas, determined in vivo from T2w anatomic MRI and the sites of microglial/macrophages activation from T2*w MRI, showed that the nanoparticle-enhanced MRI reflected the change of the distribution of Iba-1+-microglia/macrophages over time of four weeks after stoke. Our MRI and post-mortem histological data also correlated with time-dependent measurements of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines as the predominant phenotypic transformation in the active microglia/macrophages after stoke.

Treatments targeting pro-inflammatory microglia/macrophages and treatments enhancing regulatory/anti-inflammatory features of microglia/macrophages would provide attractive therapeutic opportunities for cerebral stroke, especially those promoting neurovascular remodeling during stroke recovery.1,3,4,12,13,15,16 Therefore, it is vital for great clinical relevance to delineate the time course of the underlying changes in microglial/macrophage activation occurring during stroke recovery,2,43–46 and to non-invasively monitor the longitudinal development of inflammation in the brain of stroke subjects. Since MRI is widely used in clinical practice, a nanoparticle enhanced MRI method for imaging the inflammatory response in vivo would support investigations comparing the efficacy of treatments.24 We previously applied FePt nanoparticle-enhanced MRI to measure neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s mice.26 In this study, the FePt nanoparticles were incorporated into phospholipid micelles (SM80s), which were tailored to minimize interaction with the reticuloendothelial system in order to extend their lifetime in the blood and to avoid the buildup of a protein corona by means of their polyethyleneglycol-coated surfaces. The addition of a polysorbate-8046–50 coating and ApoE250 provided a mechanism by which the nanoparticles were transported through the BBB via interaction with the LDL receptors in the brain. To specifically reveal neuroinflammation, the SM80s were targeted to activated microglia/macrophages by conjugating anti-Iba-1 antibodies.

We measured the MRI contrast between nonischemic and ischemic hemispheres of the brain, and the MRI contrast changes prior to and after nanoparticle injection to evaluate the activation of microglia/macrophages in rat brains up to four weeks after MCAO/RP. The injection of Iba-1-SM80s into sham-operated rats produced no significant changes in the MR contrast from one to four weeks after surgery. The injection of Iba-1-SM80s into rats subjected to the MCAO/RP resulted in significant specific alterations in the MRI contrast at one week, which became less pronounced by two to four weeks. This time course of MRI contrast changes paralleled the histological features shown by immunochemical staining for activated microglia/macrophages using anti-Iba-1 antibodies and optical microscopy. By comparing the T2*w MR images with those from the histological analysis, we demonstrated that the regions of edema and nanoparticle distribution in the MR images coincided with the regions of microglial/macrophage activation over the time course examined. These results provided comprehensive information with respect to how MRI of labeled microglia/macrophage reflects real-time microglial/macrophage activation occurring in the ischemic brain.

We found various morphological shapes and locations of the Fe+-cells at different time points over the four weeks of RP. The round shapes of the Fe+-cells found predominantly in the core infarct areas from one to two weeks were similar to the time-dependent recruitment of brain resident microglia and blood-derived macrophages after stroke.17,25,52–54 The Fe+-microglia/macrophages with extended processes were similar to the new population of active, anti-inflammatory cytokines expressing microglia/macrophages in the peri-infarct areas four weeks after stroke as we reported before.17 The pro-inflammatory response of microglia/macrophage includes increased expression of the cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, while in the regulatory/homeostatic phase, expression switches to the anti-inflammatory or reparative cytokines such as IL-10, YM1, and TGF-β, and their co-stimulatory proteins.3,39,52 Our co-localized histological analysis, with expression of these pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in active microglia/macrophages, demonstrated that a switch of the microglial/macrophage immunophenotype occurs from week two to four after MCAO/RP, as shown in previous reports that pro-inflammatory microglia/macrophages increase in numbers over the first two weeks.7 Importantly, the maximum negative ΔC value from T2*w MR imaging seen at one week coincided with the maximum expression of the pro-inflammatory markers in the activated microglia/macrophages in the core infarct regions, while decreasing negative ΔC values coincided with the anti-inflammatory microglia/macrophages in the peri-infarct regions during week two to four. These findings suggested that combining targeted paramagnetic nanoparticles with MRI constituted a novel approach to monitor the spatiotemporal profile of inflammation and microglial/macrophage activation in living animal.55,56

We found several factors that interfered with the quantification of the SM80s detected by T2w and T2*w imaging. The hypointensities in the T2*w MR images in the infarcted region of the brain appeared against a hyperintense background due to the cytotoxic edema in the core infarct areas, particularly at later stages after MCAO/RP. This led to the finding of, for example, a positive R/L contrast value Ca = (IR – IL)/IL in the T2*w MR images from the group of four-week MCAO/RP rats, which did not correctly reflect the obvious presence of hypointense regions surrounding core infarct areas that contained Iba-1+-active microglia/macrophages confirmed by histology. To exclude this edema interference, we employed the image contrast change (ΔC = Ca – Cp) obtained from pre-(Cp) and after-(Ca) injection of Iba-1-SM80s. The contrast change provided a quantitative measure (supplementary Figure 2) of the delivery of the nanoparticles to the infarcted tissue consistent with those from both T2*w MRI and histology. This technique produced a contrast change value of ΔC = 0.00 for the sham rats. MCAO/RP occasionally induced hemorrhage in rat brain. The iron in hemorrhages may be expected to enhance the T2*w image and interfere with the evaluation of the location of activated microglia/macrophages. To circumvent this potential issue, we subjected animals to two MRI scans at each designated time point: the first of T2w and T2*w scans was performed prior to nanoparticle injection, while the second was performed 24 h after nanoparticle injection. The data from the first scans were used as a baseline image to remove any potential effect of a hemorrhage, allowing the presence and distribution of nanoparticle-bound microglia/macrophages to be accurately determined. Unexpectedly, this experimental design turned out to be necessary for the MRI data evaluation to exclude the interference of stroke-induced brain edema.

One final concern in this work was the question of whether repeated injections of nanoparticles would build up in the brain and render useless our attempts to follow the time course of microglial/macrophage activation in individual rats. It was possible that microglia/macrophages retained nanoparticles in brain tissue for more than the one-week minimum between injections. MR images from the sham rats showed no such retention, even though they received up to three injections at one, two, and four weeks. The MRI data obtained from the MCAO/RP rats also showed no retention indicating that iron from the FePt cores was metabolized within the week between injections. The histological analysis also showed that multiple injections of SM80s did not lead to the accumulation of Fe within the brain tissue.

These initial studies revealed the potential for the use of FePt magnetic nanoparticles when using MR imaging to delineate the regions of microglial/macrophage activation within the infarcted region of the stroke brain. Our current positive results can support a future effort to explore the characteristics of the FePt particles. In particular, a concerted effort would be desirable to explore the composition of the SIPP micelles for optimizing their penetration of the BBB and their delivery to brain regions whose perfusion was compromised in stroke. We have not examined the relationship between antibody surface density and BBB penetration. This also applies to the question of optimal lipid composition of the micelles and the density of the Iba-1 on their surfaces. Future studies will utilize this novel approach to monitor the neuroinflammatory and recovery progression in animal model of stroke with therapeutic interventions.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X20953913 for Longitudinal monitoring of microglial/macrophage activation in ischemic rat brain using Iba-1-specific nanoparticle-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging by Laurel O Sillerud, Yirong Yang, Lisa Y Yang, Kelsey B Duval, Jeffrey Thompson and Yi Yang in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a NIH/NINDS 1R21NS091710 to Yi Yang.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author’s contributions: LOS performed the MRI design and data analysis, synthesized the SM80s, and wrote the manuscript. YYR performed the MRI scans, colocalization imaging analysis and Pearson’s correlation, and manuscript editing. LYY performed the histological measurements and the MR imaging analysis. KBD performed the MR imaging analysis, cell counting, and manuscript editing. JT performed the histological studies and manuscript editing. YY obtained the grant, conceived and designed the experiments, performed the MCAO surgery, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Yong HYF, Rawji KS, Ghorbani S, et al. The benefits of neuroinflammation for the repair of the injured central nervous system. Cell Mol Immunol 2019; 16: 540–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ceulemans AG, Zgavc T, Kooijman R, et al. The dual role of the neuroinflammatory response after ischemic stroke: modulatory effects of hypothermia. J Neuroinflammation 2010; 7: 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai Q, Xue M, Yong VW. Microglia and macrophage phenotypes in intracerebral haemorrhage injury: therapeutic opportunities. Brain 2020; 143:1297–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz M, Deczkowska A. Neurological disease as a failure of brain-immune crosstalk: the multiple faces of neuroinflammation. Trends Immunol 2016; 37: 668–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin WN, Shi SX, Li Z, et al. Depletion of microglia exacerbates postischemic inflammation and brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 2224–2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pimenova AA, Marcora E, Goate AM. A tale of two genes: microglial Apoe and Trem2. Immunity 2017; 47: 398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor RA, Sansing LH. Microglial responses after ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage. Clin Dev Immunol 2013; 2013: 746068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Truettner JS, Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Posttraumatic therapeutic hypothermia alters microglial and macrophage polarization toward a beneficial phenotype. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 2952–2962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, et al. The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity 2017; 47: 566–581 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lampron A, Elali A, Rivest S. Innate immunity in the CNS: redefining the relationship between the CNS and Its environment. Neuron 2013; 78: 214–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin R, Yang G, Li G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: role of inflammatory cells. J Leukoc Biol 2010; 87: 779–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelderblom M, Leypoldt F, Steinbach K, et al. Temporal and spatial dynamics of cerebral immune cell accumulation in stroke. Stroke 2009; 40: 1849–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulke E, Gelderblom M, Magnus T. Danger signals in stroke and their role on microglia activation after ischemia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2018; 11: 1756286418774254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cotrina ML, Lou N, Tome-Garcia J, et al. Direct comparison of microglial dynamics and inflammatory profile in photothrombotic and arterial occlusion evoked stroke. Neuroscience 2017; 343: 483–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thiel A, Heiss WD. Imaging of microglia activation in stroke. Stroke 2011; 42: 507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faustino J, Chip S, Derugin N, et al. CX3CR1-CCR2-dependent monocyte-microglial signaling modulates neurovascular leakage and acute injury in a mouse model of childhood stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019; 39: 1919–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Y, Salayandia VM, Thompson JF, et al. Attenuation of acute stroke injury in rat brain by minocycline promotes blood–brain barrier remodeling and alternative microglia/macrophage activation during recovery. J Neuroinflammation 2015; 12: 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yenari MA, Kauppinen TM, Swanson RA. Microglial activation in stroke: therapeutic targets. Neurotherapeutics 2010; 7: 378–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor RM, Huber DL, Monson TC, et al. Multifunctional iron platinum stealth immunomicelles: targeted detection of human prostate cancer cells using both fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging. J Nanopart Res 2011; 13: 4717–4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor RM, Huber DL, Monson TC, et al. Structural and magnetic characterization of superparamagnetic iron platinum nanoparticle contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. J Vac Sci Technol B Nanotechnol Microelectron 2012; 30: 2C101–2C1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sillerud LO. Quantitative [Fe]MRI determination of the dynamics of PSMA-targeted SPIONs discriminates among prostate tumor xenografts based on their PSMA expression. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018; 48: 469–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sillerud LO. Quantitative [Fe]MRI of PSMA-targeted SPIONs specifically discriminates among prostate tumor cell types based on their PSMA expression levels. Int J Nanomedicine 2016; 11: 357–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor RM, Severns V, Brown DC, et al. Prostate cancer targeting motifs: expression of ανβ3, neurotensin receptor 1, prostate specific membrane antigen, and prostate stem cell antigen in human prostate cancer cell lines and xenografts. Prostate 2012; 72: 523–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sillerud LO, Solberg NO, Chamberlain R, et al. SPION-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of Alzheimer’s disease plaques in AbetaPP/PS-1 transgenic mouse brain. J Alzheimers Dis 2013; 34: 349–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ito D, Tanaka K, Suzuki S, et al. Enhanced expression of Iba1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1, after transient focal cerebral ischemia in rat brain. Stroke 2001; 32: 1208–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tafoya MA, Madi S, Sillerud LO. Superparamagnetic nanoparticle-enhanced MRI of Alzheimer’s disease plaques and activated microglia in 3X transgenic mouse brains: contrast optimization. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017; 46: 574–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor RM, Sillerud LO. Paclitaxel-loaded iron platinum stealth immunomicelles are potent MRI imaging agents that prevent prostate cancer growth in a PSMA-dependent manner. Int J Nanomedicine 2012; 7: 4341–4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, et al. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments – the ARRIVE guidelines. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 991–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y, Estrada EY, Thompson JF, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-mediated disruption of tight junction proteins in cerebral vessels is reversed by synthetic matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor in focal ischemia in rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007; 27: 697–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, Kimura-Ohba S, Thompson JF, et al. Vascular tight junction disruption and angiogenesis in spontaneously hypertensive rat with neuroinflammatory white matter injury. Neurobiol Dis 2018; 114: 95–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y, Thompson JF, Taheri S, et al. Early inhibition of MMP activity in ischemic rat brain promotes expression of tight junction proteins and angiogenesis during recovery. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 1104–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Y, Yang LY, Orban L, et al. Non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation reduces blood–brain barrier disruption in a rat model of ischemic stroke. Brain Stimul 2018; 11: 689–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson C and Paxinos G. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press, Second Edition, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q, Lau A, Morris TJ, et al. A syntaxin 1, Galpha(o), and N-type calcium channel complex at a presynaptic nerve terminal: analysis by quantitative immunocolocalization. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 4070–4081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bolte S, Cordelieres FP. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J Microsc 2006; 224: 213–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rojas S, Martin A, Arranz MJ, et al. Imaging brain inflammation with [(11)C]PK11195 by PET and induction of the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor after transient focal ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007; 27: 1975–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schroeter M, Dennin MA, Walberer M, et al. Neuroinflammation extends brain tissue at risk to vital peri-infarct tissue: a double tracer [11C]PK11195- and [18F]FDG-PET study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2009; 29: 1216–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morizawa YM, Hirayama Y, Ohno N, et al. Reactive astrocytes function as phagocytes after brain ischemia via ABCA1-mediated pathway. Nat Commun 2017; 8: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colton CA. Heterogeneity of microglial activation in the innate immune response in the brain. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2009; 4: 399–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giunti D, Parodi B, Cordano C, et al. Can we switch microglia’s phenotype to foster neuroprotection? Focus on multiple sclerosis. Immunology 2013; 141: 328–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 2010; 32: 593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varin A, Mukhopadhyay S, Herbein G, et al. Alternative activation of macrophages by IL-4 impairs phagocytosis of pathogens but potentiates microbial-induced signalling and cytokine secretion. Blood 2010; 115: 353–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eyo UB, Dailey ME. Microglia: key elements in neural development, plasticity, and pathology. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2013; 8: 494–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iadecola C, Anrather J. The immunology of stroke: from mechanisms to translation. Nat Med 2011; 17: 796–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fowler JH, McQueen J, Holland PR, et al. Dimethyl fumarate improves white matter function following severe hypoperfusion: involvement of microglia/macrophages and inflammatory mediators. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 1354–1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fukumoto Y, Tanaka KF, Parajuli B, et al. Neuroprotective effects of microglial P2Y1 receptors against ischemic neuronal injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019; 39: 2144–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ambruosi A, Khalansky AS, Yamamoto H, et al. Biodistribution of polysorbate 80-coated doxorubicin-loaded [14C]-poly(butyl cyanoacrylate) nanoparticles after intravenous administration to glioblastoma-bearing rats. J Drug Target 2006; 14: 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramge P, Unger RE, Oltrogge JB, et al. Polysorbate-80 coating enhances uptake of polybutylcyanoacrylate (PBCA)-nanoparticles by human and bovine primary brain capillary endothelial cells. Eur J Neurosci 2000; 12: 1931–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yusuf M, Khan M, Khan RA, et al. Polysorbate-80-coated, polymeric curcumin nanoparticles for in vivo anti-depressant activity across BBB and envisaged biomolecular mechanism of action through a proposed pharmacophore model. J Microencapsul 2016; 33: 646–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Wu M, Zhang N, et al. Mechanisms of enhanced antiglioma efficacy of polysorbate 80-modified paclitaxel-loaded PLGA nanoparticles by focused ultrasound. J Cell Mol Med 2018; 22: 4171–4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maleklou N, Allameh A, Kazemi B. Preparation, characterization and in vitro-targeted delivery of novel Apolipoprotein E-based nanoparticles to C6 glioma with controlled size and loading efficiency. J Drug Target 2016; 24: 348–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schilling M, Besselmann M, Muller M, et al. Predominant phagocytic activity of resident microglia over hematogenous macrophages following transient focal cerebral ischemia: an investigation using green fluorescent protein transgenic bone marrow chimeric mice. Exp Neurol 2005; 196: 290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rawlinson C, Jenkins S, Thei L, et al. Post-ischaemic immunological response in the brain: targeting microglia in ischaemic stroke therapy. Brain Sci 2020; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia-Culebras A, Duran-Laforet V, Pena-Martinez C, et al. Myeloid cells as therapeutic targets in neuroinflammation after stroke: specific roles of neutrophils and neutrophil-platelet interactions. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 2150–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neuwelt A, Langsjoen J, Byrd T, et al. Ferumoxytol negatively enhances T2 -weighted MRI of pedal osteomyelitis in vivo. J Magn Reson Imaging 2017; 45: 1241–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neuwelt A, Sidhu N, Hu CA, et al. Iron-based superparamagnetic nanoparticle contrast agents for MRI of infection and inflammation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 204: W302–W313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X20953913 for Longitudinal monitoring of microglial/macrophage activation in ischemic rat brain using Iba-1-specific nanoparticle-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging by Laurel O Sillerud, Yirong Yang, Lisa Y Yang, Kelsey B Duval, Jeffrey Thompson and Yi Yang in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism