Abstract

Objective

To investigate the explicitness and variability of the definition of periodontal health in the current scientific literature.

Material and methods

The authors conducted a systematic literature review using PubMed and CENTRAL (2013‐01/2019‐05) according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and the guidelines of the Meta‐analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) statement.

Results

A total of 51 papers met the predefined inclusion criteria. Of these, 13 papers did not report any explicit definitions of periodontal health. Out of the 38 remaining articles, half of them used a reference to support their definition and half of them not. The studies published in periodontics‐related journals or those that scored a low risk of bias for the methodical quality presented more explicit and valid definitions. Probing pocket depth was the most frequently used individual parameter for defining periodontal health. However, there were substantial variations in the methods of measurement and cut‐off values.

Conclusions

Given the diversity of periodontal health definitions, a cross‐study comparison is difficult. The results of this review may be useful in making others aware of the significance of standardizing the definition of a healthy periodontium.

Keywords: definition, periodontal health, periodontium, systematic review

1. INTRODUCTION

The main objective of periodontal care is to reach and maintain a healthy periodontium. The definition of periodontal health plays a crucial role in population surveillance and the determination of critical therapeutic targets for clinicians. 1 Most studies traditionally regarded that a healthy periodontium is the opposite of case definitions of periodontal disease, as does the World Health Organization (WHO) defining health as an absence of illness. 2 Specifically, periodontal health refers to a state free from inflammation and characterized by shallow pockets and the absence of gingival bleeding. 3 However, there are a variety of case definitions, 4 , 5 , 6 and these definitions refer to an array of clinical signs and symptoms, such as probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment loss (CAL) and bleeding on probing (BOP). 7 Consequently, we assume that there is heterogeneity in the definitions of periodontal health. The definition of periodontal health should be consistent, facilitating comparison of clinical studies. 8 Periodontal health was recently defined as the absence of clinically detected inflammation by the 2018 World Workshop of the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) and the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP). 9 This EFP/AAP definition is mainly based on PPD and BOP scores. To date, no overview of periodontal health definitions has been conducted. Therefore, this systematic review (SR) investigates the current scientific literature related to the definition of periodontal health.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Protocol development

The protocol for this SR was developed “a priori,” following an initial discussion among members of the research team according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the guidelines of PRISMA and MOOSE.

2.2. Search strategy

A structured literature search of the National Library of Medicine, Washington, DC (PubMed‐MEDLINE), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Cochrane‐CENTRAL) was performed up to May 2019. Since the Centers for Disease Control and the American Academy of Periodontology (CDC/AAP) case definition of periodontal disease was updated in 2012, this report covers all studies published and cited since January 2013. We hand‐searched all of the reference lists of selected papers. This forward citation check was carried out in four rounds to identify additional published work that could meet the eligibility criteria of the study, so‐called “snowball procedure.” For details regarding the search terms used, see Appendix S1.

2.3. Eligibility criteria

Publications were included only when they (a) were original studies, (b) were conducted in a human population, (c) were published in English, (d) contained a defined group of periodontal health or a non‐defined control group as an opposite to the defined periodontal disease, and (e) their definitions described measurements and identified thresholds.

2.4. Screening and selection

Two reviewers (AL and RZT) screened the titles and abstracts of the studies obtained during the search for eligible papers independently. After the screening, the reviewers read the full texts of eligible papers in detail. Any disagreement concerning eligibility was resolved by consensus, and if conflict persisted, the decision was settled through arbitration led by a third reviewer (DES). The papers that met all the selection criteria were processed for data extraction.

2.5. Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity across studies was detailed according to the following factors: study design, published journal type, subject characteristics, potential confounding factors, measurement tools and procedures, the number of explicit definitions, clinical parameters and cut‐off values.

2.6. Methodological assessment of risk of bias

The two reviewers independently scored the methodological qualities of each study as well (AL and RZT). The appropriate critical appraisal checklists from the Joanna Briggs Institute were used depending on the study design of the paper. 10 Studies that met 80% of the criteria were considered to have a low risk of bias. And 60% to 79% was a moderate one; 40% to 59% criteria were substantial one; and less than 40%, high one. 11

2.7. Data extraction and analysis

The characteristics of the published journal type, study design, country, sample frame, sample size, group, age, gender, smoking status, medical condition, examination area, measurement tool, probing location and definition of periodontal health were extracted. Papers that included detailed measuring parameters and clear cut‐off values were regarded as having an “explicit definition”. 12 Moreover, the “explicit definition” papers that used references to support their definitions were viewed as having a “valid definition”. 13 The extracted criteria for periodontal health were recorded with Microsoft Excel 2017 (Microsoft). All quantitative analyses were conducted with SPSS Statistics 25 (SPSS Inc).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results

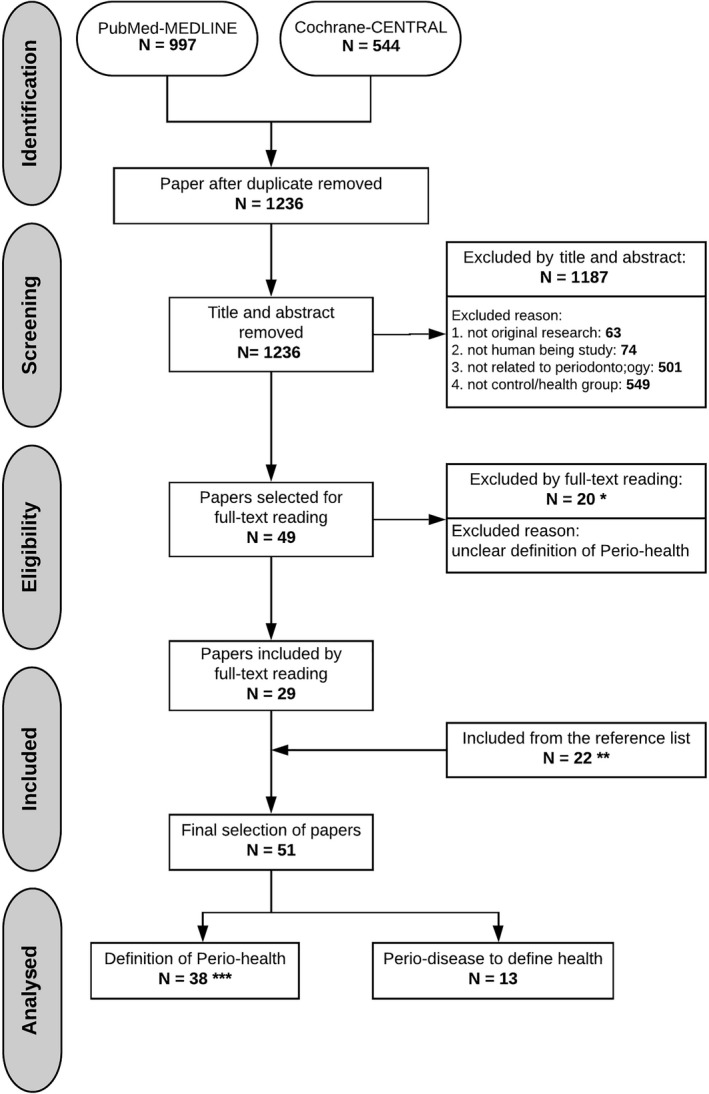

The search through online databases resulted in 1236 unique studies (Figure 1). The initial screening of the titles and abstract resulted in 49 studies that went on to full‐text review. Then, a detailed reading of the full texts was performed. Two independent reviewers excluded 20 studies (Appendix S2), leaving 29 eligible papers. Furthermore, a manual search through the reference list of the 29 papers led reviewers to identify 22 additional relevant studies (Appendices S3 and S4). Finally, a total of 51 studies were included for the evaluation of the definition of periodontal health. Among the selected papers, 38 provided a definition of periodontal health. Thirteen studies did not report an explicit periodontal health definition and rather referenced periodontal health as the opposite of disease. This study outlines the characteristics of the included papers. These characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review. *see Appendix S2, **see Appendices S3 and S4, *** see Table 3. Abbreviations: Perio‐health, periodontal health; Perio‐disease, periodontal disease.

TABLE 1.

Overview of the studies processed for data extraction

|

Reference (year) Type of journal Risk of bias |

Study design Sample frame Country |

Sample size of all Healthy group: number/ age/ gender |

Smoking status Medical condition |

Examination area Measurement tool Probing location |

Explicit definition of periodontal health or Opposite of periodontal disease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mourão et al, 2013 34 Medical journal Substantial |

RCT study Dental clinic Brazil |

ALL: (n = 60) Periodontal health group: (n = 20) 48.6 ± 7.4, ♀: 12/ ♂: 8 |

Not recorded Not recorded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Inter‐proximal sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Jones et al, 2013 35 Dental journal Substantial |

RCT study General population United Kingdom |

ALL: (n = 369) 6‐month group: (n = 125) 37.1 ± 10.4, ♀: 68 (54.4%)/ ♂: 57 (45.6%) 12‐month group: (n = 122) 39.6 ± 10.8, ♀: 79 (64.8%)/ ♂: 43 (35.2%) 24‐month group: (n = 122) 36.4 ± 10.6, ♀: 88 (72.1%)/ ♂: 34 (27.9%) |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth WHO probe Six sites |

Basic Periodontal Examination (BPE) Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Graziani et al, 2018 36 Periodontal journal Moderate |

RCT study Dental hospital Italy |

ALL: (n = 60) Group 1: (n = 15) 28.7 ± 9.8, ♀: 6 (40%)/ ♂: 9 (60%) Group 2: (n = 14) 26.1 ± 3.7, ♀: 8 (57%)/ ♂: 6 (43%) Group 3: (n = 16) 26.4 ± 5.2, ♀: 9 (56%)/ ♂: 7 (44%) Group 4: (n = 15) 26.4 ± 5.4, ♀: 8 (53%)/ ♂: 7 (47%) |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Six sites |

Consensus report of the 5th European Workshop in periodontology 29 © 2020 The Authors. International Journal of Dental Hygiene published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Sukhtankar et al, 2013 37 Medical journal Moderate |

Non‐randomized experimental study Department of periodontics and oral implantology India |

© 2020 The Authors. International Journal of Dental Hygiene published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd (24‐55), ♀: 20/ ♂: 20 © 2020 The Authors. International Journal of Dental Hygiene published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd © 2020 The Authors. International Journal of Dental Hygiene published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Site unclear |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Sharma et al, 2014 38 Medical journal Moderate |

Non‐randomized experimental study Dental hospital India |

© 2020 The Authors. International Journal of Dental Hygiene published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd © 2020 The Authors. International Journal of Dental Hygiene published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd 25‐60 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Six sites |

© 2020 The Authors. International Journal of Dental Hygiene published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd 39 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Guentsch et al, 2014 40 Periodontal journal Moderate |

Non‐randomized experimental study Dental hospital Germany |

ALL: (n = 30) Periodontal health group: (n = 15) 26 (23‐39), ♀: 11/ ♂: 4 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Six sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Hassan et al, 2015 41 Medical journal Moderate |

Non‐randomized experimental study General population Egypt |

ALL: (n = 30) Periodontal health group: (n = 10) 37.81 ± 8.3, ♀: 6/ ♂: 4 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Michigan 0 probe Six sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Leite et al, 2014 42 Medical journal Low |

Non‐randomized experimental study General hospital Brazil |

ALL: (n = 55) Periodontal health group: (n = 55) 33.18 ± 6.42, ♀: 67%/ ♂: 33% |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Michigan 0 probe Four sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Al‐Hamoudi et al, 2018 43 Dental journal Low |

Non‐randomized experimental study Dental hospital Saudi Arabia |

ALL: (n = 137) Obese patients without CP: (n = 34) 37.5 (31‐42), ♀: 2/ ♂: 32 Non‐obese patients without CP: (n = 33) 36.2 (33‐42), ♀: 0/ ♂: 33 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 periodontal probe Six sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Muthu et al, 2015 44 Dental journal Moderate |

Non‐randomized experimental study Dental hospital India |

ALL: (n = 220) (35‐50), ♀: 96/ ♂: 124 Control group: (n = 90) |

Excluded Excluded |

Examination area unclear Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Raber‐Durlacher et al, 2013 45 Medical journal High |

Cohort study Dental hospital Netherlands |

ALL: (n = 18) 41.8 ± 13.4 (19‐64) ♀: 11 (61%)/ ♂: 7 (39%) Periodontal health group: (n = 5) |

Not recorded Not recorded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Four sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Ricardo et al, 2015 15 Medical journal Moderate |

Cohort study Population United States |

ALL: (n = 10,755): 41.5 ± 0.5, ♀: 50%/ ♂: 50% CKD (+) without periodontitis group: (n = 1,142): 51.9 ± 1.2, ♀: 62.1%/ ♂: 37.9% CKD (‐) without periodontitis group: (n = 8,795): 39.6 ± 0.4, ♀: 49.8%/ ♂: 50.2% |

Recorded Chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Site unclear |

CDC/AAP case definition 6 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Lee et al, 2017 46 Medical journal Substantial |

Cohort General population Korea |

ALL: (n = 354,850) Periodontal health group: (n = 154,824) 40‐49:46.8%, 50‐59:27.6%, 60‐69:19.6%, 70‐79:6%. ♀: 49.2%, ♂: 50.8% |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Inter‐proximal sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Lourenço et al, 2014 18 Periodontal journal Moderate |

Case‐control study Division of Graduate Periodontics Brazil |

ALL: (n = 97) Periodontal health group: (n = 27) 24.2 ± 6.9, ♀: 77.8%/ ♂: 22.2% |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Site unclear |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Zimmermann et al, 2013 47 Periodontal journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital Brazil |

ALL: (n = 78) NW non‐periodontitis (NP) group: (n = 20) 42.9 ± 7.2, ♀: 14/ ♂: 6 Obese non‐periodontitis group: (n = 18) 43.2 ± 7.4, ♀: 14/ ♂: 4 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Six sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Apatzidou et al, 2013 48 Dental journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Department of periodontology Greece |

ALL: (n = 78) Healthy individuals: (n = 27) 31 ± 5, ♀: 15/ ♂: 12 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Six sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Ebersole et al, 2013 49 Medical journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Population United States |

ALL: (n = 80) Healthy adults: (n = 30) 31.4 ± 6.8, ♀: 46.7%/ ♂: 53.3% |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Inter‐proximal sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Rathnayake et al, 2013 50 Periodontal journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital Sweden |

ALL: (n = 451) PD‐ group: (303) 42.6 ± 15.5, gender unclear |

Recorded Recorded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Four sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Wang et al, 2013 51 Medical journal High |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital China |

ALL: (n = 16) 30‐65, gender unclear |

Excluded Excluded |

Examination area unclear Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Gursoy et al, 2013 52 Periodontal journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Population Finland |

ALL: (n = 230) Control subject group: (n = 81) 47.9 ± 5.7, ♀: 64.2%/ ♂: 35.8% |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Four sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Kebschull et al, 2013 53 Dental journal Substantial |

Cross‐sectional Clinic of post‐doctoral periodontics United States |

ALL: (n = 310) “Healthy” group: (n = 69) 45.7 ± 11.6 (24‐76), ♀: 50.8%/ ♂: 49.2% |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Six sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Salazar et al, 2013 54 Periodontal journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Population Germany |

ALL: (n = 400) Healthy periodontium group: (n = 20) 48.6 ± 11.4, ♀: 50%/ ♂: 50% |

Recorded Excluded |

Examination area unclear SHIP‐2: PCP11 probe; SHIP‐TREND: PCPUNC probe 15 Site unclear |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Gokhale et al, 2013 55 Medical journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Department of Periodontics India |

ALL: (n = 120) 30‐60 Periodontal health group: (n = 30) |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Four sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Wara‐aswapati et al, 2013 56 Periodontal journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional General hospital Thailand |

ALL: (n = 35) Control individuals without periodontitis: (n = 16) 34.0 ± 15.8, ♀: 14/ ♂: 2 |

Not recorded Excluded |

Area unclear UNC‐15 probe Site unclear |

Armitage classification 17 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Javed et al, 2014 57 Periodontal journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital Pakistan |

ALL: (n = 88) Controls: (n = 28) 51.7 ± 12.9, ♀: 0/ ♂: 28 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Hu‐Friedy probe Six sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Kim et al, 2013 58 Dental journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital Korea |

ALL: (n = 125) 57.85 ± 1.03, ♀: 48/ ♂: 77 |

Recorded Excluded |

Area unclear WHO probe Six sites |

WHO community periodontal index of treatment needs 59 Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Pushparani et al, 2014 60 Periodontal journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Department of periodontology India |

ALL: (n = 600) Control healthy individual: (n = 150) 35.46 ± 610.74, ♀: 70/ ♂: 80 Type 2DM without periodontitis: (n = 150) 46.26 ± 10.02, ♀: 72/ ♂: 78 |

Excluded Excluded |

Area unclear Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Armitage classification 17 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Shetty et al, 2016 61 Medical journal moderate |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital India |

ALL: (n = 120) Healthy group: (n = 30) |

Excluded Excluded |

Area unclear Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Panezai et al, 2018 62 Medical journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital Pakistan |

ALL: (n = 86) Healthy group: (n = 14) 44.4 ± 6.6, ♀: 5/ ♂: 9 |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth Hu‐Friedy probe Four sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Huang et al, 2018 63 Medical journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital China |

ALL: (n = 68) ♀: 31 (43 ± 12.1)/ ♂: 37 (47 ± 11.7) Healthy group: (n = 20) |

Not recorded Excluded |

Area unclear Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Papathanasiou et al, 2014 64 Periodontal journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Population United States |

ALL: (n = 42) periodontally healthy group: (n = 14) 26.3 ± 2.6, ♀: 78.6%/ ♂: 21.4% |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Six sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Mesa et al, 2014 65 Periodontal journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital Spain |

ALL: (n = 77) Periodontal health group: (n = 36) 46.25 (19‐79), ♀: 46/ ♂: 31 |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Six sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Schjetlein et al, 2014 14 Medical journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional study General hospital Diabetes patients Denmark |

ALL: (n = 62) 57.0 (51‐60), ♀: 28/ ♂: 34 Without periodontitis group: (n = 49) 57.0 (51‐61), ♀: 24/ ♂: 25 |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth WHO probe Site unclear |

Periodontal Screening Index Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Ramírez et al, 2014 66 Dental journal Low |

Cross‐sectional General hospital Colombia |

ALL: (n = 44) Periodontal health group: (n = 22) 40.6 ± 8.6, ♀: 17 (77.3%)/ ♂: 5 (22.7%) |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Beklen and Tsaous Memet, 2014 67 Medical journal Substantial |

Cross‐sectional General hospital Turkey |

ALL: (n = 20) Periodontal health group: (n = 10) 33‐39, gender unclear |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Inter‐proximal sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Singh et al, 2014 68 Periodontal journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Department of periodontics and oral implantology India |

ALL: (n = 106) Periodontally healthy individuals: (n = 22) 27.5 (22‐50), ♀: 16/ ♂: 6 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Six sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Duran‐Pinedo et al, 2014 69 Medical journal Substantial |

Cross‐sectional General hospital United States |

ALL: (n = 13) Periodontally healthy individuals: (n = 6) Age unclear, gender unclear |

Excluded Excluded |

Examination area unclear Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Tabari et al, 2013 70 Dental journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Department of Periodontology Iran |

ALL: (n = 50) Individuals with a healthy periodontium: (n = 25) 20‐45, ♀: 11 (44%)/ ♂: 14 (56%) |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Four sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Tabari et al, 2013 70 Periodontal journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Department of Periodontology Iran |

ALL: (n = 40) Periodontally healthy individuals: (n = 20) 33.85 ± 6.84, ♀: 65%/ ♂: 35% |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Four sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Garneata et al, 2015 16 Medical journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional study General hospital Romania |

ALL: (n = 238) 57.0 (50.0‐64.8), ♀: 40%/ ♂: 60% Periodontal health group: (n = 58) 55.5 (42.3‐61.0), ♀: 43%/ ♂: 57% |

Recorded Stable chronic hemodialysis patients |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Torrungruang et al, 2015 71 Medical journal Substantial |

Cross‐sectional study Population Thailand |

ALL: (n = 1,362) No/mild periodontitis: (n = 479) 46.6 ± 4.4, ♀: 211/ ♂: 268 |

Recorded Not recorded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Six sites |

CDC/AAP case definition 6 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Ghallab et al, 2015 72 Periodontal journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital Egypt |

ALL: (n = 50) Periodontal health group: (n = 10) 47.8 ± 2.9, ♀: 5/ ♂: 5 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Michigan 0 probe Six sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Lavu et al, 2015 73 Medical journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital India |

ALL: (n = 400) Periodontal health group: (n = 200) 29.64 ± 5.5 (20‐55), ♀: 52.4%/ ♂: 47.5% |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth UNC‐15 probe Six sites |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Kurşunlu et al, 2015 74 Dental journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional study Department of periodontology Turkey |

ALL: (n = 80) Periodontally healthy subjects (n = 20) |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Chaiyarit et al, 2015 75 Dental journal High |

Cross‐sectional General hospital Thailand |

ALL: (n = 90) Healthy subjects: (n = 30) 54.4 ± 11.03 (35‐75), ♀: 17/ ♂: 13 |

Not recorded Excluded |

Examination area unclear Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Armitage classification 17 : Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Özcan et al, 2015 76 Dental journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Department of periodontology Turkey |

ALL: (n = 72) Healthy subjects: (n = 23) 34.50 ± 7.09 (35‐75), ♀: 11/ ♂: 12 |

Excluded Excluded |

Examination area unclear Michigan 0 probe Site unclear |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Kirst et al, 2015 77 Medical journal Substantial |

Cross‐sectional General hospital United States |

ALL: (n = 50) Healthy controls: (n = 25) |

Not recorded Excluded |

Examination area unclear Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Velosa‐Porras et al, 2016 78 Dental journal Low |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital Colombia |

ALL: (n = 150) Mean = 50.2 Periodontal health group: (n = 75) ♀: 44/♂: 31 |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth Electronic probe Site unclear |

Armitage classification 17 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Prodan et al, 2016 79 Medical journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Population Netherlands |

ALL: (n = 261) 22.6 (18.0,32.0) ♀: 116/ ♂: 145 |

Excluded Excluded Student of university |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Site unclear |

Dutch periodontal screening index (DPSI) 80 Explicit definition of periodontal health |

|

Noguera‐Julian et al, 2017 81 Medical journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital United States |

ALL: (n = 50) 45.3 (37.0‐53.0) ♀: 17/ ♂: 32/ Trans: 1 |

Recorded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Inter‐proximal sites |

CDC/AAP case definition 6 : Opposite of periodontal disease |

|

Sağlam et al, 2017 82 Dental journal Moderate |

Cross‐sectional Dental hospital Turkey |

ALL: (n = 60) ♀: 33/ ♂: 27 Periodontal health group: (n = 20) 30.62 ± 7.65 |

Excluded Excluded |

Full mouth Probe type unclear Six sites |

Explicit definition of periodontal health |

3.2. Methodological quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was used to estimate the potential risk of bias and is presented in detail in Appendices S5.1‐5. The estimated potential risk of bias was low for 15 studies, moderate for 25 studies, substantial for eight studies, and high for three studies.

3.3. Study characteristics

The papers were published in journals of different categories, targeting periodontology (29%), dentistry (29%) and general medicine (41%). The studies were designed as cross‐sectional studies (37/51), longitudinal studies (4/51), and randomized or non‐randomized allocated control studies (10/51). A total number of 372 983 individuals were enrolled in the studies, ranging from 18 to 354 850 individuals for each one (mean: 7313, SD: 49 660, median: 78). Most publications were authored by research groups in India (14%) and the United States (12%).

Most studies (82%) recruited patients from a hospital setting with comorbidities such as diabetes, 14 chronic kidney disease 15 or chronic haemodialysis. 16 Concerning confounding factors, such as smoking habits and medical condition, 28 of the studies excluded participants with smoking habits. Those with complicated medical conditions were excluded from 45 studies (Table 1).

3.4. Measurement methods

In 39 out of the 51 papers, a full‐mouth assessment was conducted (Table 1). Various types of periodontal probes were used. Twenty‐four studies did not report the details of the probe, 16 studies used the UNC‐15 probe, and four studies used the Michigan 0 probe. The number and location of probing sites varied. Four sites (mesiobuccal, mesiolingual, distobuccal and distolingual) per tooth were used in 8 studies, and six sites (mesiobuccal, midbuccal, distobuccal, mesiolingual, midlingual and distolingual) per tooth were used in 17 studies. Moreover, five studies specifically measured the indicators at the location of the inter‐proximal sites.

3.5. Presence of an explicit or valid definition according to journal type, study design and risk of bias

A precise definition of periodontal health is offered in 38 (75%) of the included studies. The remaining 13 papers provided the references and defined the opposite of disease as periodontal health (Table 2). An explicit definition with a supporting reference was reported in 19 papers. In contrast, the other 19 studies only used a definition rather than indicating any reference (Table 2; for details, see Appendix S6). The two most frequently used references were the Armitage classification (1999), 17 used in 22 papers, and the CDC/AAP case definition, 6 used in five papers. None of the papers reporting details of the classification followed the original proposed definition strictly, but a wide variance was applied (Appendices S7.1‐2).

TABLE 2.

Classification of included papers according to explicit and valid definitions

| ALL = 51 | Full‐text reading | N (%) | Definition analysing | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Definition of health a | 38 (74.5) | 1a | Definition of health with reference b | 19 (37.25) |

| 1b | Definition of health without reference | 19 (37.25) | |||

| 2 | Disease to define health | 13 (24.5) | 2a | Definition of disease with reference | 12 (23.5) |

| 2b | Definition of disease without reference | 1 (2) |

The “only definition” and “reference and definition” groups were regarded as explicit definitions of periodontal health.

The “reference and definition” group was regarded as a valid definition of periodontal health.

The number of explicit and valid periodontal health definitions was sub‐analysed according to journal categories, study designs and resource of patients as well as assessed methodological risk of bias. In the periodontal journals, the definitions used were more explicit (87%) than those used in the dental or medical journals (Appendix S8.1). Moreover, the papers collected from a department of periodontology tended to provide explicit definitions (91%) compared with other studies. The studies scoring a low risk of bias for the methodical quality had more valid definitions (Appendix S8.2).

3.6. Clinical parameters and cut‐off values

Table 3 summarizes the different periodontal health definitions used (38 studies). Notably, Loureço provided two definitions of periodontal health in the one study. 18 Therefore, the table contains 39 definitions. The table also presents the differences regarding cut‐off points, PPD, CAL, BOP, and other relevant information for each study. Probing pocket depth was almost used for all definitions (n = 35), whereas BOP was used in less than half of the cases (n = 16). Probing pocket depth appeared in nine studies used as a single criterion. A combination of PPD with CAL appeared in 10 studies. A combination of PPD with BOP appeared in five studies, and a triple set of PPD, CAL, and BOP was used in 10 papers.

TABLE 3.

Summary of periodontal health definitions

| Papers (N)/definitions (n) | PPD (mm) | CAL (mm) | BOP (%) | Other | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 38/ n = 39 | n = 35 | n = 24 | n = 16 | ||

| 1 | <3 | Beklen et al, 2014 67 | |||

| 2 | <3 | Özcan et al, 2015 76 | |||

| 3 | <3 | Duran‐Pinedo et al, 2014 69 | |||

| 4 | <3.5 | Jones et al, 2013 35 | |||

| 5 | <3.5 | Schjetlein et al, 2014 14 | |||

| 6 | <4 | Garneata et al, 2015 16 | |||

| 7 | <4 | Gursoy et al, 2013 52 | |||

| 8 | <4 | No clinical sign + no X‐ray bone loss | Ramírez et al, 2014 66 | ||

| 9 | <5 | Prodan et al, 2016 79 | |||

| 10 | <3 | Kirst et al, 2015 77 | |||

| 11 | <3 | Kim et al, 2013 58 | |||

| 12 | <3 | Graziani et al, 2018 36 | |||

| 13 | No X‐ray bone loss | Rathnayake et al, 2013 50 | |||

| 14 | =0 | =0 | No clinical sign + no X‐ray bone loss | Huang et al, 2018 63 | |

| 15 | <3 | <3 | Wang et al, 2013 51 | ||

| 16 | <3 | =0 | Guentsch et al, 2014 40 | ||

| 17 | <3 | =0 | Tabari et al, 2014 70 | ||

| 18 | <3 | =0 | Pushparani et al, 2014 60 | ||

| 19 | <3 | =0 | GI = 0 + PI = 0 | Ghallab et al, 2015 72 | |

| 20 | <3 | =0 | GI = 0 + PI = 0 | Hassan et al, 2015 41 | |

| 21 | <3 | <2 | Mesa et al, 2014 65 | ||

| 22 | <3 | <3 | Zimmermann et al, 2013 47 | ||

| 23 | <4 | <4 | Kebschull et al, 2013 53 | ||

| 24 | <3 | <10 | Tabari et al, 2013 70 | ||

| 25 | <3 | <10 | Apatzidou et al, 2013 48 | ||

| 26 | <3 | <30 | Salazar et al, 2013 54 | ||

| 27 | <4 | <15 | Muthu et al, 2015 44 | ||

| 28 | <4 | <10 | Raber‐Durlacher et al, 2013 45 | ||

| 29 | <3 | =0 | =0 | Kurşunlu et al, 2015 74 | |

| 30 | <3 | <3 | =0 | Mourão et al, 2013 34 | |

| 31 | <3 | =0 | =0 | No clinical sign + no history | Lavu et al, 2015 73 |

| 32 | <3 | =0 | <10 | Singh et al, 2014 68 | |

| 33 | <3 | <1 | <10 | Sukhtankar et al, 2013 37 | |

| 34 | <3 | <2 | <20 | No X‐ray bone loss | Sağlam et al, 2017 82 |

| 35 a | <3 | <3 | <10 | Lourenço et al, 2014 18 | |

| <4 | <4 | <5 | Lourenço et al, 2014 18 | ||

| 36 | <3 | <3 | <10 | No X‐ray bone loss | Leite et al, 2014 42 |

| 37 | <3 | ≤3 | <20 | Papathanasiou et al, 2014 64 | |

| 38 | <4 | <2 | <10 | Ebersole et al, 2013 49 |

Abbreviations: BOP, bleeding on probing; CAL, clinical attachment level; PDD, probing pocket depth.

Lourenço et al provided two sets of periodontally healthy definition in one paper. 'Gray shades' means a single criterion or combination involving PPD/CAL/BOP to define periodontal health.

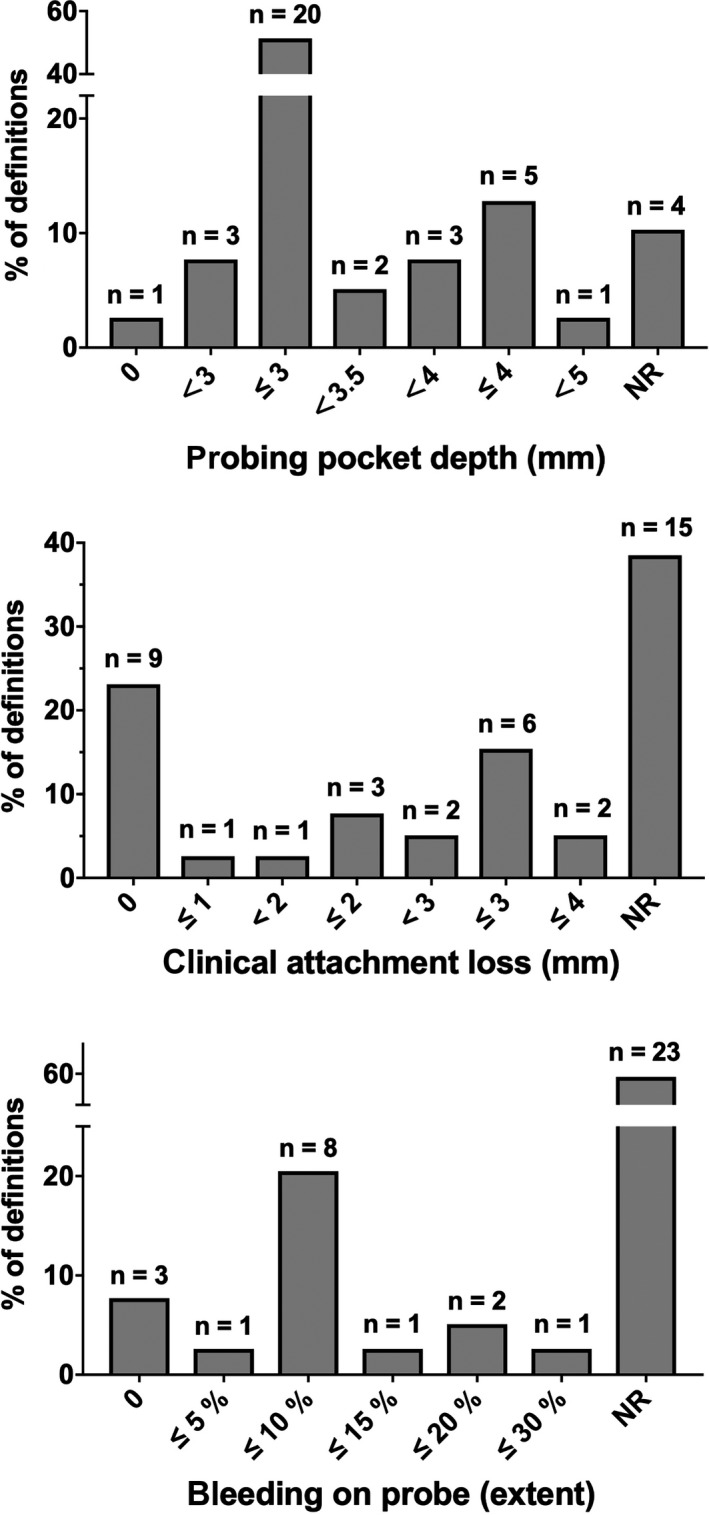

Figure 2A‐C presents the numbers of papers using a threshold. The most frequently used PPD cut‐off was ≤3 mm, which appeared in 20 studies. However, 11 studies reported a threshold of 3.5 mm or higher. A considerable amount of variety was observed concerning the CAL threshold, ranging from 0 to 4 mm. Nine studies reported the absence of CAL, and 15 studies did not report CAL (Figure 2B). Figure 2C demonstrates that among the reported BOP thresholds, the most commonly used was 10% sites, but the majority of the included papers (n = 23) did not report BOP.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of severity and extent for PPD (A), CAL (B) and BOP (C) used to define periodontal health among 36 studies showed by number and percentage. Notably, one of studies provided two definitions of periodontal health. Therefore, the total number of definitions is 37

4. DISCUSSION

This SR aims to conduct an exploratory analysis of the definitions of periodontal health and the methods used to measure a healthy periodontium. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first SR exclusively dedicated to exploring a variety of periodontal health definitions. Although the significance of periodontal health is well known, a universal, formal definition did not exist until the World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri‐Implant Diseases and Conditions, which was organized by the EFP and the AAP. 9 The main findings of this review were that (a) there is a lack of an explicit definition of periodontal health and consequently, a lack of application of references, (b) there is significant heterogeneity in measuring methods, and (c) there are considerable inconsistencies in the different periodontal parameters and cut‐off values used.

Operational definitions and consistent criteria for a healthy periodontium were not provided in the majority of papers. The studies that did not provide a definition or a reference were excluded (Appendix S2). Some did provide a definition but lacked a reference, and some only gave a reference but lacked a definition. Only 37% (19 of 51) of the papers included in this study reported an explicit definition with detailed clinical parameters and cited a reference. The two most commonly cited references were the 1999 International Workshop for the Classification of Periodontal Disease 17 (21 out of 31) and the CDC/AAP case definition for population‐based studies of periodontitis 6 (5 out of 31) (Appendix S6). Even when a proper reference was used, there existed a variety of interpretations. Misuse of the original criteria of the references created even more heterogeneity and introduces inevitable bias. As with the definition of periodontitis, it was difficult to achieve the goal of reproducing and analysing the results from different studies. 7

A periodontal pocket is the most common sign of periodontitis and easy to detect and assess in the clinical practice using various periodontal probes. The regularization of using periodontal probes will raise the accuracy of the process of diagnosing the condition and evaluating the treatment outcome. 19 , 20 The present SR has identified a great amount of variety in the methods and materials used, such as the periodontal probing methods, particularly the type of probe and probing site. The procedure of measuring PPD and CAL was described as being assessed by either four or six sites per tooth. The number of sites used and especially the proportion of interdental sites assessed may influence the outcome. In any case, uniformity in material and methods can reduce the measurement bias. The EFP/AAP workshop recommended the use of an International Organization for Standardization (ISO) periodontal probe. 9

A cut‐off or a reference point is needed to distinguish health from recurring signs and symptoms of periodontal disease. 8 A wide range of parameters and cut‐offs were identified in the present systematic review. Probing pocket depth was the most frequently used periodontal parameter. Given the fact that it is rather easy to detect and measure, PPD has been recognized for many years as the essential parameter for the diagnosis of periodontal health and disease. 21 Half of the studies (51%) reported a threshold of PPD ≤3 mm. This cut‐off value is also used to identify periodontal case types of health. 22 In contrast, there were still 11 (29%) definitions that used the threshold of 3.5 mm PPD or deeper. The cut‐off PPD ≤3 mm might be excessively strict if a population is assessed such that only a few end up in the category of healthy. This may be the reason that researchers in large epidemiology studies stretch the PPD cut‐off point. For instance, Hugoson used the following cut‐off of periodontal health and disease: ≤10% sites with PPD ≥4 mm. 23 , 24 Nevertheless, even the largest cut‐off value of PPD did not exceed 5 mm in the current review. A systematic review reported that probing depth up to 6 mm or even more should be taken into account as a high‐risk factor to predict further disease progression in periodontal patients. 25

Other frequently used parameters are CAL and BOP. Clinical attachment loss, the second most frequently used parameter, varies across studies. This was used in three (8%) studies as the single parameter and in 21 (55%) as an adjunct to PPD. The most commonly used threshold using CAL is the absence of attachment loss. As ageing comes with natural bone loss, some CAL is physiological. Therefore, the absence of CAL is likely due to the outdated concept. Periodontal health is identified as the absence of any deficit of supporting tissues. 8 The strict and sometimes idealistic definition of absence of CAL can result in an overestimation of disease. The third most commonly used parameter, BOP, is never used alone, but serves as an adjunct. Notably, criteria consisting of BOP and PPD appeared in five (13%) articles, whereas BOP was only used in 16 out of 39 definitions (41%). The most frequently used BOP cut‐off is less than 10%. Stable periodontium can manifest as the absence of extensive BOP. 26 The cut‐off values of BOP used to identify health and disease vary. A large‐scale epidemiological study used a cut‐off of <20% BOP, 23 without referencing evidence. Patients with BOP sites ≥16% have a higher chance of losing attachment. 27 After active non‐surgical treatment during the maintenance/supportive phase, the risk of tooth loss is considerably greater for patients with 30% bleeding. 28 Overall, a limited amount of positive symptoms for BOP is accepted in the healthy periodontium. Interestingly, the most frequently used cut‐off value (BOP <10%) is consistent with the EFP/AAP classification. Nevertheless, there is no clear evidence to support the used cut‐off values. Compared to previous values, bleeding sites of 10% might underestimate the number of people with a healthy periodontium.

The current review is not without limitations. After a full‐text reading and analysis of the reference lists, 22 extra papers were included (for details, see Figure 1). Although this snowball procedure was conducted carefully, it remains possible that some studies describing periodontal health were not included in our search. Searching for definitions of periodontal health is complicated as it is often used as a category describing the opposite of disease. Thus, periodontal health often does not appear as a search term in the title and abstracts of studies. This also explains why the snowball procedure reveals more papers than those obtained from the initial search and selected based on the given criteria. A recommendation for further studies is that there is a need for evaluations such as what probe to use and what measurements to collect, in order to make a proper diagnosis for daily clinical practice and epidemiological studies.

The definition of periodontal health recommended by the EFP/AAP Workshop was defined as less than 10% of sites having BOP and PPD ≤3 mm in intact periodontium or ≤4 mm in reduced periodontium. 9 Previous studies took CAL into account as a critical factor in describing accumulated lesions and the susceptibility of the disease. 29 , 30 However, loss of periodontal attachment has not been incorporated, partly because the newly proposed definition focuses on the current status of different periodontium. Periodontal inflammatory activity or inactivity can be identified according to the extent of BOP and PPD instead of CAL. Similar to the assessment of periodontal inflammatory burden, 31 non‐bleeding pockets are regarded as periodontal tissue without inflammation. The quantity of inflammation is related to the inflamed periodontal surface area, which is calculated by the PPD values of bleeding teeth.

Periodontal health can also present in an anatomically reduced periodontium. 1 In other words, periodontal health does not merely mean that there is an absence of supporting tissue deficit. It also refers to an individual's level of comfort, the stability of a functioning periodontium, and one's psychological and social well‐being. This concept of holistic periodontal health has not been taken into account in this paper. Notably, the feasibility of directly regarding the definition of periodontal health in a reduced periodontium (PPD ≤4 mm and BOP ≤10%) as the treatment goal among patients remains uncertain. However, a certain PPD value after treatment needs to be interpreted in the light of variance in susceptibility and personalized medicine. Lang and Tonetti built a functional diagram to assess periodontal risk in supportive periodontal therapy, which can help clinicians distinguish whether a treatment goal is reached or not. 32 Moreover, the number of residual pockets with a probing depth of ≥5 mm to a certain extent reflects the degree of success of periodontal treatment, which is different from the PPD threshold in the new definition. In the randomized clinical trial, 33 the subjects presenting ≤4 sites with PD ≥5 mm at one year represented a successful treatment outcome. Therefore, the endpoint of therapy should seek the most optimal balance between over‐ and underestimation of health status among treated periodontal patients. It is important to acknowledge the distinction between the diagnoses of periodontal health of initial patients versus treated patients. For the latter, a more flexible, comprehensive and detailed assessment would be recommended.

5. CONCLUSION

This SR revealed a variety of definitions of periodontal health in existing scientific literature. This heterogeneity was measured according to study characteristics, measurement methods, explicit definitions, references and cut‐off values used. The definition of periodontal health proposed by the EFP/AAP Workshop offers an opportunity for the field to standardize and achieve uniformity in terms of methodologies in order to draw comparisons between different studies. This study also revealed that the number of people thought to have periodontal disease is likely overestimated due to the strict cut‐off value.

6. CLINICAL RELEVANCE

6.1. Scientific rationale for the study

There is no standard reference for periodontal health, and the diagnostic properties of the various definitions have not been studied.

6.2. Principal finding

Marked heterogeneity in the definitions of different measuring methods and clinical parameters in periodontal health may be affecting interpretations of research.

6.3. Practical implications

The new definition of periodontal health proposed by the EFP/AAP workshop in 2018 offers an opportunity to standardize and unify the cut‐off values of clinical parameters, which would allow for a better comparison of clinical studies and support research and decision‐making.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

An Li, first author, contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. Renske Z. Thomas, overall daily supervisor, contributed to the design of study, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the manuscript. Luc van der Sluis contributed to the design of study and critically revised the manuscript. Geerten‐Has Tjakkes contributed to the design and critically revised the manuscript. Dagmar Else Slot contributed to the conception and design of the study, supported the analysis and interpretation of the data, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of this work, ensuring its integrity and accuracy.

Supporting information

Appendix S1‐S9

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the help of Dr Diane Black, lecturer of language centre of University Groningen, with proofreading.

Li A, Thomas RZ, Van der Sluis L, Tjakkes G‐H, Slot DE. Definitions used for a healthy periodontium—A systematic review. Int J Dent Hygiene. 2020;18:327–343. 10.1111/idh.12438

Funding information

China Scholarship Council funds the PhD position for the first author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lang NP, Bartold PM. Periodontal health. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45(Suppl 20):S9‐S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Preamble to the Constitution of World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference. New York, NY: World Health Organization; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mariotti A, Hefti AF. Defining periodontal health. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(Suppl 1):S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van der Velden U. Purpose and problems of periodontal disease classification. Periodontol 2000. 2005;39(1):13‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tonetti MS. Advances in the progression of periodontitis and proposal of definitions of a periodontitis case and disease progression for use in risk factor research. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(Suppl 6):210‐213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population‐based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78(7 Suppl):1387‐1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Savage A, Eaton KA, Moles DR, Needleman I. A systematic review of definitions of periodontitis and methods that have been used to identify this disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(6):458‐467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mariotti A. Defining periodontal health. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(Suppl 1):S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chapple ILC, Mealey BL, Van Dyke TE, et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri‐Implant Diseases and Conditions. J Periodontol. 2018;89(Suppl 1):S74‐S84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Joanna Briggs Institute . Critical appraisal tools. 2018. http://joannabriggs.org/research/critical‐appraisal‐tools.html.

- 11. Salzer S, Slot DE, Van der Weijden FA, Dorfer CE. Efficacy of inter‐dental mechanical plaque control in managing gingivitis–a meta‐review. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42(Suppl 16):S92‐S105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Madden‐Fuentes RJ, McNamara ER, Lloyd JC, et al. Variation in definitions of urinary tract infections in spina bifida patients: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):132‐139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Metsemakers WJ, Kortram K, Morgenstern M, et al. Definition of infection after fracture fixation: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials to evaluate current practice. Injury. 2018;49(3):497‐504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schjetlein AL, Jorgensen ME, Lauritzen T, Pedersen ML. Periodontal status among patients with diabetes in Nuuk, Greenland. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2014;73:26093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ricardo AC, Athavale A, Chen J, et al. Periodontal disease, chronic kidney disease and mortality: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Garneata L, Slusanschi O, Preoteasa E, Corbu‐Stancu A, Mircescu G. Periodontal status, inflammation, and malnutrition in hemodialysis patients ‐ is there a link? J Ren Nutr. 2015;25(1):67‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4(1):1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lourenço TG, Heller D, Silva‐Boghossian CM, Cotton SL, Paster BJ, Colombo AP. Microbial signature profiles of periodontally healthy and diseased patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41(11):1027‐1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ramachandra SS, Mehta DS, Sandesh N, Baliga V, Amarnath J. Periodontal probing systems: a review of available equipment. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2011;32(2):71‐77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Breen HJ, Rogers PA, Lawless HC, Austin JS, Johnson NW. Important differences in clinical data from third, second, and first generation periodontal probes. J Periodontol. 1997;68(4):335‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hefti AF. Periodontal probing. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1997;8(3):336‐356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sweeting LA, Davis K, Cobb CM. Periodontal Treatment Protocol (PTP) for the general dental practice. J Dent Hyg. 2008;82(Suppl 3):16‐26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hugoson A, Sjodin B, Norderyd O. Trends over 30 years, 1973–2003, in the prevalence and severity of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(5):405‐414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hugoson A, Norderyd O. Has the prevalence of periodontitis changed during the last 30 years? J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(8 Suppl):338‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Renvert S, Persson GR. A systematic review on the use of residual probing depth, bleeding on probing and furcation status following initial periodontal therapy to predict further attachment and tooth loss. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(Suppl 3):82‐89; discussion 81‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lang NP, Adler R, Joss A, Nyman S. Absence of bleeding on probing. An indicator of periodontal stability. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17(10):714‐721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lang NP, Joss A, Orsanic T, Gusberti FA, Siegrist BE. Bleeding on probing. A predictor for the progression of periodontal disease? J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13(6):590‐596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matuliene G, Pjetursson BE, Salvi GE, et al. Influence of residual pockets on progression of periodontitis and tooth loss: results after 11 years of maintenance. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(8):685‐695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tonetti MS, Claffey N. Advances in the progression of periodontitis and proposal of definitions of a periodontitis case and disease progression for use in risk factor research. Group C consensus report of the 5th European Workshop in Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(Suppl 6):210‐213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eke PI, Dye BA, Wei L, et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol. 2015;86(5):611‐622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nesse W, Abbas F, van der Ploeg I, Spijkervet FK, Dijkstra PU, Vissink A. Periodontal inflamed surface area: quantifying inflammatory burden. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(8):668‐673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lang NP, Tonetti MS. Periodontal risk assessment (PRA) for patients in supportive periodontal therapy (SPT). Oral Health Prev Dent. 2003;1(1):7‐16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Feres M, Soares GM, Mendes JA, et al. Metronidazole alone or with amoxicillin as adjuncts to non‐surgical treatment of chronic periodontitis: a 1‐year double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39(12):1149‐1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mourão LC, Moutinho H, Canabarro A. Additional benefits of homeopathy in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2013;19(4):246‐250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jones C, Macfarlane T, Milsom K, Ratcliffe P, Wyllie A, Tickle M. Patient perceptions regarding benefits of single visit scale and polish: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Graziani F, Palazzolo A, Gennai S, et al. Interdental plaque reduction after use of different devices in young subjects with intact papilla: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Dent Hyg. 2018;16(3):389‐396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sukhtankar L, Kulloli A, Kathariya R, Shetty S. Effect of non‐surgical periodontal therapy on superoxide dismutase levels in gingival tissues of chronic periodontitis patients: a clinical and spectophotometric analysis. Dis Markers. 2013;34(5):305‐311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sharma A, Astekar M, Metgud R, Soni A, Verma M, Patel S. A study of C‐reactive protein, lipid metabolism and peripheral blood to identify a link between periodontitis and cardiovascular disease. Biotech Histochem. 2014;89(8):577‐582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wood N, Johnson RB, Streckfus CF. Comparison of body composition and periodontal disease using nutritional assessment techniques: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(4):321‐327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Guentsch A, Pfister W, Cachovan G, et al. Oral prophylaxis and its effects on halitosis‐associated and inflammatory parameters in patients with chronic periodontitis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2014;12(3):199‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hassan SH, El‐Refai MI, Ghallab NA, Kasem RF, Shaker OG. Effect of periodontal surgery on osteoprotegerin levels in gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, and gingival tissues of chronic periodontitis patients. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:341259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leite AC, Carneiro VM, Guimaraes MC. Effects of periodontal therapy on C‐reactive protein and HDL in serum of subjects with periodontitis. Rev Brasil Cir Cardiovasc. 2014;29(1):69‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Al‐Hamoudi N, Abduljabbar T, Mirza S, et al. Non‐surgical periodontal therapy reduces salivary adipocytokines in chronic periodontitis patients with and without obesity. J Invest Clin Dent. 2018;9(2):e12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Muthu J, Muthanandam S, Mahendra J, Namasivayam A, John L, Logaranjini A. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy on the glycaemic control of nondiabetic periodontitis patients: a clinical biochemical study. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2015;13(3):261‐266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Raber‐Durlacher JE, Laheij AM, Epstein JB, et al. Periodontal status and bacteremia with oral viridans streptococci and coagulase negative staphylococci in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients: a prospective observational study. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(6):1621‐1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee JH, Oh JY, Youk TM, Jeong SN, Kim YT, Choi SH. Association between periodontal disease and non‐communicable diseases: a 12‐year longitudinal health‐examinee cohort study in South Korea. Medicine. 2017;96(26):e7398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zimmermann GS, Bastos MF, Dias Goncalves TE, Chambrone L, Duarte PM. Local and circulating levels of adipocytokines in obese and normal weight individuals with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2013;84(5):624‐633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Apatzidou AD, Bakirtzoglou E, Vouros I, Karagiannis V, Papa A, Konstantinidis A. Association between oral malodour and periodontal disease‐related parameters in the general population. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71(1):189‐195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ebersole JL, Schuster JL, Stevens J, et al. Patterns of salivary analytes provide diagnostic capacity for distinguishing chronic adult periodontitis from health. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(1):271‐279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rathnayake N, Akerman S, Klinge B, et al. Salivary biomarkers of oral health: a cross‐sectional study. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(2):140‐147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang J, Qi J, Zhao H, et al. Metagenomic sequencing reveals microbiota and its functional potential associated with periodontal disease. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gursoy UK, Kononen E, Huumonen S, et al. Salivary type I collagen degradation end‐products and related matrix metalloproteinases in periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(1):18‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kebschull M, Guarnieri P, Demmer RT, Boulesteix AL, Pavlidis P, Papapanou PN. Molecular differences between chronic and aggressive periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2013;92(12):1081‐1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Salazar MG, Jehmlich N, Murr A, et al. Identification of periodontitis associated changes in the proteome of whole human saliva by mass spectrometric analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40(9):825‐832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gokhale NH, Acharya AB, Patil VS, Trivedi DJ, Thakur SL. A short‐term evaluation of the relationship between plasma ascorbic acid levels and periodontal disease in systemically healthy and type 2 diabetes mellitus subjects. J Diet Suppl. 2013;10(2):93‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wara‐aswapati N, Chayasadom A, Surarit R, et al. Induction of toll‐like receptor expression by Porphyromonas gingivalis . J Periodontol. 2013;84(7):1010‐1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Javed F, Ahmed HB, Saeed A, Mehmood A, Bain C. Whole salivary interleukin‐6 and matrix metalloproteinase‐8 levels in patients with chronic periodontitis with and without prediabetes. J Periodontol. 2014;85(5):e130‐e135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kim EK, Lee SG, Choi YH, et al. Association between diabetes‐related factors and clinical periodontal parameters in type‐2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress T, Martin J, Sardo‐Infirri J. Development of the World Health Organization (WHO) community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN). Int Dent J. 1982;32(3):281‐291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pushparani DS, Anandan SN, Theagarayan P. Serum zinc and magnesium concentrations in type 2 diabetes mellitus with periodontitis. J Ind Soc Periodontol. 2014;18(2):187‐193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shetty A, Bhandary R, Thomas B, Ramesh A. A comparative evaluation of serum magnesium in diabetes mellitus type 2 patients with and without periodontitis – a clinico‐biochemical study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(12):Zc59‐zc61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Panezai J, Ghaffar A, Altamash M, Engstrom PE, Larsson A. Periodontal disease influences osteoclastogenic bone markers in subjects with and without rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(6):e0197235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Huang B, Dai Q, Huang SG. Expression of Toll‐like receptor 4 on mast cells in gingival tissues of human chronic periodontitis. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17(5):6731‐6735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Papathanasiou E, Teles F, Griffin T, et al. Gingival crevicular fluid levels of interferon‐gamma, but not interleukin‐4 or ‐33 or thymic stromal lymphopoietin, are increased in inflamed sites in patients with periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 2014;49(1):55‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mesa F, Magan‐Fernandez A, Munoz R, et al. Catecholamine metabolites in urine, as chronic stress biomarkers, are associated with higher risk of chronic periodontitis in adults. J Periodontol. 2014;85(12):1755‐1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ramírez JH, Parra B, Gutierrez S, et al. Biomarkers of cardiovascular disease are increased in untreated chronic periodontitis: a case control study. Aust Dent J. 2014;59(1):29‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Beklen A, Tsaous MG. Interleukin‐1 superfamily member, interleukin‐33, in periodontal diseases. Biotech Histochem. 2014;89(3):209‐214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Singh N, Chander Narula S, Kumar Sharma R, Tewari S, Kumar SP. Vitamin E supplementation, superoxide dismutase status, and outcome of scaling and root planing in patients with chronic periodontitis: a randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2014;85(2):242‐249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Duran‐Pinedo AE, Chen T, Teles R, et al. Community‐wide transcriptome of the oral microbiome in subjects with and without periodontitis. ISME J. 2014;8(8):1659‐1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tabari ZA, Azadmehr A, Tabrizi MA, Hamissi J, Ghaedi FB. Salivary soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand/osteoprotegerin ratio in periodontal disease and health. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2013;43(5):227‐232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Torrungruang K, Jitpakdeebordin S, Charatkulangkun O, Gleebbua Y Porphyromonas gingivalis, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, and Treponema denticola / Prevotella intermedia co‐infection are associated with severe periodontitis in a Thai population. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ghallab NA, Amr EM, Shaker OG. Expression of leptin and visfatin in gingival tissues of chronic periodontitis with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus: a study using enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay and real‐time polymerase chain reaction. J Periodontol. 2015;86(7):882‐889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lavu V, Venkatesan V, Venkata Kameswara Subrahmanya Lakka B, Venugopal P, Paul SF, Rao SR. Polymorphic regions in the interleukin‐1 gene and susceptibility to chronic periodontitis: a genetic association study. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2015;19(4):175‐181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kurşunlu SF, Ozturk VO, Han B, Atmaca H, Emingil G. Gingival crevicular fluid interleukin‐36beta (‐1F8), interleukin‐36gamma (‐1F9) and interleukin‐33 (‐1F11) levels in different periodontal disease. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60(1):77‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Chaiyarit P, Taweechaisupapong S, Jaresitthikunchai J, Phaonakrop N, Roytrakul S. Comparative evaluation of 5–15‐kDa salivary proteins from patients with different oral diseases by MALDI‐TOF/TOF mass spectrometry. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19(3):729‐737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Özcan E, Saygun NI, Serdar MA, Kurt N. Evaluation of the salivary levels of visfatin, chemerin, and progranulin in periodontal inflammation. Clin Oral Investig. 2015;19(4):921‐928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kirst ME, Li EC, Alfant B, et al. Dysbiosis and alterations in predicted functions of the subgingival microbiome in chronic periodontitis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2015;81(2):783‐793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Velosa‐Porras J, Escobar‐Arregoces F, Latorre‐Uriza C, Ferro‐Camargo MB, Ruiz AJ, Uriza‐Carrasco LF. Association between periodontal disease and endothelial dysfunction in smoking patients. Acta Odontol Latinoamericana. 2016;29(1):29‐35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Prodan A, Brand H, Imangaliyev S, et al. A study of the variation in the salivary peptide profiles of young healthy adults acquired using MALDI‐TOF MS. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0156707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Van der Velden U. The Dutch periodontal screening index validation and its application in The Netherlands. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36(12):1018‐1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Noguera‐Julian M, Guillen Y, Peterson J, et al. Oral microbiome in HIV‐associated periodontitis. Medicine. 2017;96(12):e5821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Sağlam M, Koseoglu S, Aral CA, Savran L, Pekbagriyanik T, Cetinkaya A. Increased levels of interleukin‐33 in gingival crevicular fluids of patients with chronic periodontitis. Odontology. 2017;105(2):184‐190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1‐S9