Abstract

Background

Data on opinions and experiences of aesthetic medical procedures outside the United States and Western Europe are scarce.

Aims

This study aimed to survey users and non‐users of aesthetic procedures in countries where this information is less readily available, to understand attitudes and perceptions relating to beauty.

Patients/Methods

Two independent internet‐based observational surveys were conducted. Survey 1: individuals from Colombia, Lebanon, Malaysia, Russia and Turkey who were ‘users’ or ‘non‐users’ of aesthetic medical procedures. Survey 2: individuals from Colombia, Russia, Thailand, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates who were ‘users’ of non‐surgical aesthetic treatments.

Results

Surveys 1 and 2 were completed by 300 and 160 individuals, respectively, most of whom were female (94.0% and 99%). Overall, respondents rated the eyes and smile as the most pleasing male and female facial features. Most participants (mean 82.6%; range 75%‐100%) believed maintaining a healthy lifestyle was important for ageing gracefully, and over one‐third (36.0%; 28%‐47%) believed men age more gracefully than women. The emphasis respondents placed on the importance of physical attributes vs inner feelings, internal beauty and self‐confidence varied between countries. Users were often more positive about aesthetic medical procedure outcomes than non‐users. Adequate information, good physician communication (including managing treatment expectations), treatment recommendations based on patient need and good aftercare improved treatment satisfaction.

Conclusions

The eyes and smile were key features of attractiveness, but maintaining a healthy lifestyle was consistently considered an important factor for ageing gracefully. Ensuring patients are well informed was a major determinant of treatment satisfaction.

Keywords: aesthetic medicine, beauty, botulinum toxin, health, satisfaction

1. INTRODUCTION

Perceptions of physical attractiveness, personal well‐being, and aging vary widely across cultures worldwide but despite these differences, global demand for cosmetic procedures is rising.1, 2, 3, 4 As a psychosocial factor, physical attractiveness has been linked to elevated self‐confidence and self‐esteem, and perceived improved career success, earnings, social status, academic performance and even sporting performance, although associations with actual improvements are not so clear‐cut.5, 6 The availability of a variety of elective aesthetic medical procedures now enables individuals to change aspects of their physical appearance to a greater degree than with solely cosmetic procedures. It has been shown that the motivation for elective aesthetic medical procedures is modulated by physical, psychosocial, psychological, and emotional factors, including body image, self‐esteem, education, and culture2, 7, 8 with the relative importance of each factor differing with age.9

Data on aesthetic medical procedures, particularly levels of use, expectations, and outcomes, are generally based on users from the United States and, to a lesser extent, Western Europe. Less extensive information on these procedures is available from Latin America, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, despite an international report that Brazil, South Korea, Japan, Mexico, and Colombia rank within the top seven countries for individuals seeking aesthetic surgical procedures.10 The objective of the two observational, Internet‐based surveys reported here was to assess opinions and experiences of nonsurgical aesthetic medical procedures in both users (both surveys) and nonusers (survey 1 only) of such procedures in countries where evidence was less readily available (Colombia, Lebanon, Malaysia, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Two independent surveys were undertaken using custom, Internet‐based questionnaires provided in the local language. The surveys were designed by two healthcare consulting firms (survey 1, Decision Resources Group, Burlington, MA, USA; survey 2, Opinion Health, London, UK), and members of the public were recruited and screened to determine previous use of aesthetic medical procedures (survey 1; Appendix S1) or nonsurgical aesthetic treatments (survey 2; Appendix S2). Individuals were then invited to participate in the respective surveys. Responses to survey questionnaires were translated into English for review, validation, and analysis. All questionnaire data were anonymized. Given the observational, noninterventional nature of the surveys (and in line with local legislation), ethical approval was neither required nor sought. All participants were supplied with comprehensive information regarding each survey's objective and procedures and provided informed consent. Modest remuneration was given for participation.

2.1. Survey 1: Perceptions of beauty and attitudes to aesthetic medical procedures

Survey 1 was undertaken in February 2015 in Colombia, Lebanon, Malaysia, Russia and Turkey. A screening questionnaire was completed by men and women aged 30 to 70 years to determine if they had (“users”) or had not (“nonusers”) undergone any of the following aesthetic medical procedures: aesthetic laser/light/energy‐based procedure, body implant, botulinum toxin, breast augmentation/reconstruction, chemical peel, dermal filler, facial implants, liposuction, microdermabrasion, or noninvasive fat reduction.

Individuals who agreed to participate in the survey (men, n = 8; women, n = 282) then completed a 30‐ to 45‐minute questionnaire on general perception statements related to aging gracefully (healthy living, healthy skin, feeling beautiful, no deep wrinkles, overall appearance), the five most important features of male and female beauty from a predetermined list of brow, cheeks, eyes, forehead, hair, jawline/chin, lips, nose, skin texture, skin tone/color, or smile, if they knew someone who has undergone an aesthetic procedure and their attitudes toward these procedures (level of agreement with “aesthetic medical procedures make people look more confident/beautiful/youthful/refreshed”; “botulinum toxin injections can help: people to age gracefully/reduce signs of aging”). Previous users were also asked how satisfied they were with the previous aesthetic medical procedure(s) they had undergone.

Study procedures were managed by healthcare consulting firm, Decision Resources Group (Burlington, MA, USA). Descriptive analyses of the survey data were undertaken using SPSS software (IBM Corporation).

2.2. Survey 2: Patient expectations and experiences of nonsurgical aesthetic treatment

Survey 2 was performed in September 2015 in Colombia, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) but only included individuals who had prior experience of nonsurgical aesthetic treatments, including dermal filler injections, expression wrinkle injections, facial reshaping injections, hair treatment, laser treatment, skin cleansing, skin rejuvenation, or teeth whitening. Men and women (aged ≥18 years) completed a 10‐minutes questionnaire regarding their satisfaction with, and expected outcomes for, these treatments.

Participants were asked about their level of agreement with the following reasons for undertaking nonsurgical aesthetic treatment: My look is very important for me; maintaining my appearance is part of my lifestyle; I care about how I look in front of other people; having visible wrinkles/signs of aging is not an option for me; and I'll look less good compared with others if I don't receive nonsurgical aesthetic treatment. Other questions related to procedure satisfaction, reasons for dissatisfaction, and in‐clinic experiences of initial contact, consultation, treatment, and follow‐up. Study procedures were managed by the healthcare consulting firm, Opinion Health (London, UK).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Survey 1: Perceptions of beauty and attitudes to aesthetic medical procedures

3.1.1. Characteristics of the study population

In the overall population (N = 300), the majority of participants were from urban areas (90.7%), female (94.0%), married (75.3%), and between 30 and 39 years of age (61.0%). As only 6.0% of respondents were male, the results from the survey were not separated according to sex and are only presented in aggregate. Demographic characteristics were broadly similar across countries (N = 60 in each country), except for annual household income with the percentage of participants from a low‐income household ranging from 0% in Lebanon to 70% in Columbia (Table 1). Among users (N = 30 in each country), laser/light/energy‐based treatments were the most common first aesthetic medical procedure except for Lebanon where botulinum toxin was the most common first procedure. Mean ages at first aesthetic procedure ranged from 30.9 in Malaysia to 37.3 years in Lebanon.

Table 1.

Demographic and other baseline characteristics of survey 1 respondents

|

Colombia (N = 60) |

Lebanon (N = 60) |

Malaysia (N = 60) |

Russia (N = 60) |

Turkey (N = 60) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, female, n (%) | 60 (100) | 50 (83.3) | 58 (96.7) | 55 (91.7) | 59 (98.3) |

| Residence, n (%) | |||||

| Urban | 58 (96.7) | 50 (83.3) | 50 (83.3) | 57 (95.0) | 57 (95.0) |

| Suburban | 0 | 8 (13.3) | 9 (15.0) | 0 | 2 (3.3) |

| Rural | 2 (3.3) | 2 (3.3) | 1 (1.7) | 3 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) |

| Marital status, married, n (%) | 37 (61.7) | 45 (75.0) | 45 (75.0) | 51 (85.0) | 48 (80.0) |

| Age (mean), y | 40.3 | 40.4 | 35.9 | 40.5 | 37.5 |

| Age group, n (%) | |||||

| 30‐39 y | 28 (46.7) | 31 (51.7) | 51 (85.0) | 32 (53.3) | 41 (68.3) |

| 40‐49 y | 23 (38.3) | 23 (38.3) | 6 (10.0) | 17 (28.3) | 16 (26.7) |

| 50‐59 y | 9 (15.0) | 4 (6.77) | 2 (3.3) | 11 (18.3) | 3 (5.0) |

| 60‐70 y | 0 | 3 (5.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Annual household income category, n (%) | |||||

| Low | 42 (70.0) | 0 | 12 (20.0) | 22 (36.7) | 7 (11.7) |

| Moderate | 16 (26.7) | 20 (33.3) | 30 (50.0) | 22 (36.7) | 21 (35.0) |

| High | 2 (3.3) | 40 (66.7) | 18 (30.0) | 16 (26.7) | 32 (53.3) |

| First aesthetic medical procedure (users only) |

Colombia (n = 30) |

Lebanon (n = 30) |

Malaysia (n = 30) |

Russia (n = 30) |

Turkey (n = 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First aesthetic procedure a , n (%) | |||||

| Aesthetic laser/light/energy‐based procedure | 9 (30.0) | 7 (23.3) | 12 (40.0) | 12 (40.0) | 16 (53.3) |

| Botulinum toxin | 2 (6.7) | 10 (33.3) | 3 (10.0) | 6 (20.0) | 3 (10.0) |

| Breast augmentation/reconstruction | 3 (10.0) | 0 | 2 (6.7) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) |

| Chemical peel | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 6 (20.0) | 7 (23.3) |

| Dermal filler | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 4 (13.3) | 2 (6.7) | 1 (3.3) |

| Facial implants | 2 (6.7) | 5 (16.7) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 1 (3.3) |

| Liposuction | 5 (16.7) | 2 (6.7) | 4 (13.3) | 0 | 1 (3.3) |

| Microdermabrasion | 4 (13.3) | 1 (3.3) | 0 | 2 (6.7) | 0 |

| Noninvasive fat reduction | 3 (10.0) | 3 (10.0) | 3 (10.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Age at first aesthetic procedure, mean (y) | 31.6 | 37.3 | 30.9 | 34.2 | 30.7 |

No patients had undergone body implants so this procedure has not been included in the table.

3.1.2. Aging gracefully

The majority of participants in each country considered that “aging gracefully” involved maintaining a healthy lifestyle (mean of all five countries, 82.6%; range, 75%‐100%) and having healthy looking skin (77.8%; 70%‐85%). The largest inter‐country disparity was that only 15% of Columbian participants considered that wrinkles were incompatible with aging gracefully compared with 67% from Lebanon. Just over one‐third of participants (36.0%; range, 28%‐47%) considered that men aged more gracefully than women. Generally, there were only small differences between users and nonusers with the exception that more users than nonusers agreed that wrinkles were incompatible with aging gracefully (overall means of 42.0% and 28.8%, respectively) and that men age more gracefully than women (42.0% and 30.0%, respectively).

On a personal level, ≥80% of respondents, irrespective of country, agreed that they wanted their outward appearance to match how they felt inside (except for Lebanese respondents, of whom 75% agreed with this statement), to age gracefully and to look fresh and not tired. Looking younger than their chronological age was less important in Colombia and Lebanon (58% in both) than in the other countries (75%‐87%). A similar percentage of users and nonusers wanted their outward appearance to match inner feeling, with a mean from all five countries of 81.2% for nonusers and 84.2% for users, although in Lebanon, more users than nonusers had this personal preference (users, 87%; nonusers, 63%).

3.1.3. Beauty ideals

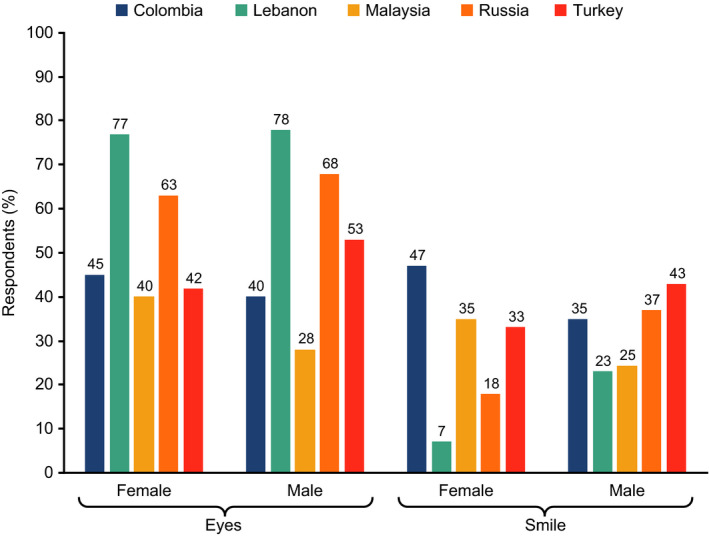

Of 11 predefined facial features, overall the eyes and smile were most frequently ranked in the top two features considered important for beauty for both men and women (Figure 1 and Appendix S3). Within each country, the percentage of respondents who perceived the eyes to be an important facial feature was similar for both male and female beauty, with the largest differences between the sexes seen in Malaysian and Turkish subjects. The percentage of respondents who ranked smile as a top two feature for male and female beauty varied within countries. In Colombia and Malaysia, more respondents perceived smile to be an important feature for female beauty compared with male beauty, whereas more respondents from Lebanon, Russia, and Turkey perceived the smile to be an important feature for male beauty compared with female beauty. Irrespective of sex and country of origin, respondents thought that the eyes were the most beautiful facial feature.

Figure 1.

Ideals of female and male beauty; the two most important features, as ranked by the participants (all respondents, n = 60 per country). All participants were asked to rank the five most important facial features for male and female beauty from among a preselected list (including brow, cheeks, eyes, jawline, lips, nose, skin texture, smile). The two most selected facial features are presented here. Data source: Survey 1

Common responses to open questions concerning appealing male features were attractive, natural smiles, and eye shape (almond in Lebanon and Russia and round in Malaysia and Colombia). Wrinkles around the eyes were considered attractive only when accompanying smiling. For questions concerning female features, the responses generally mirrored those given in the predefined facial features question with attractive eyes and smiles more commonly cited as being important. Interestingly, Malaysian respondents considered a fair skin complexion important for female beauty, while tanned skin was preferred for males.

In open responses related to the relative importance of physical and personality traits as attributes of beauty, Russian and Lebanese participants placed a greater emphasis on physical aspects, whereas Turkish participants tended to focus more on feelings and personal presentation. Malaysians and Colombians placed significant emphasis on internal beauty, focusing more on self‐confidence and other personality attributes as opposed to physical traits.

3.1.4. Facial features that respondents would want to modify about themselves in aesthetic medical procedures

Almost a quarter of the respondents, although only 10% of Russian participants, stated their nose was the feature they would change with frequent nasal complaints including excessive size, width, or flatness. Although the eyes were considered the most important feature determining beauty, only 8.0% of the respondents stated it was a feature of their own they would want to change. There were some marked variations between countries, such as much larger percentages of Lebanese and Russian participants selecting lips and jawline, respectively, and no few Lebanese participants wishing to change their skin texture. Detailed results are provided in Appendix S4.

3.1.5. Awareness of, and attitudes toward, aesthetic procedures

Nearly all (97%) of Colombian respondents knew at least one person who had undergone an aesthetic procedure and consequently had the greatest awareness of costs for undertaking a procedure. In contrast, many respondents from Malaysia (45%), Turkey (30%), and Lebanon (28%) did not know anyone who had undergone a procedure. In each country, a smaller percentage of users (up to 23%) than nonusers (up to 67%) of aesthetic treatments did not know anyone who had undergone a procedure. A similar percentage of users (mean of 77%) and nonusers (mean of 75%) stated that they had discussed aesthetic procedures with their family but discussions with friends were more common among users (mean of 65%) than nonusers (mean of 37%).

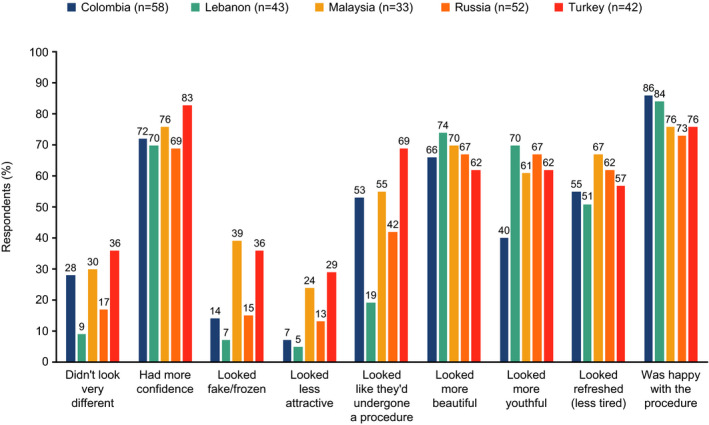

3.1.6. Respondent opinions of outcomes of aesthetic medical procedures in other people

Overall, respondents had positive opinions of the impact of aesthetic medical procedures on the beauty, self‐confidence, and well‐being of people they knew, although response patterns varied widely between countries (Figure 2). Malaysian and Turkish respondents were generally more critical of the outcomes, yet were the respondents who considered the recipients had more confidence (Figure 2). Users were generally more positive than nonusers (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Respondent opinions of outcomes of aesthetic medical procedures in other people (all respondents). The data correspond to the percentage of respondents strongly or moderately agreeing with the statement: After the procedure, the person/people. Data source: Survey 1. The question was answered only by people knowing ≥ 1 person undergoing an aesthetic procedure

3.1.7. Aesthetic medical procedures involving botulinum toxin

Respondents in all countries were relatively well aware of aesthetic medical procedures involving botulinum toxin, irrespective of whether the respondent was a user or nonuser (Colombia: 70% of users vs 73% of nonusers; Lebanon: 87% vs 77%; Malaysia: 83% vs 73%; Russia: 80% vs 83%; Turkey: 53% vs 80%). Of the respondents who had heard of botulinum toxin procedures, only 7%‐23% of nonusers stated that they would undergo such a procedure compared with 23%‐47% of users who had actually undergone this procedure. Most respondents considered that botulinum toxin injections can reduce signs of aging (82% of users and 56% of nonusers) and roughly half of the respondents considered they helped people to age gracefully (54% and 47%, respectively). In general, Russian respondents, irrespective of if they were users or nonusers, tended to be less convinced about positive effects of botulinum toxin, whereas Lebanese respondents gave the most favorable responses.

Among respondents who were aware of botulinum toxin injections, only 6.4% of users compared with 14.4% of nonusers considered that they were unsafe, with the most concerns over the safety of the procedure seen in Malaysian and Russian nonusers.

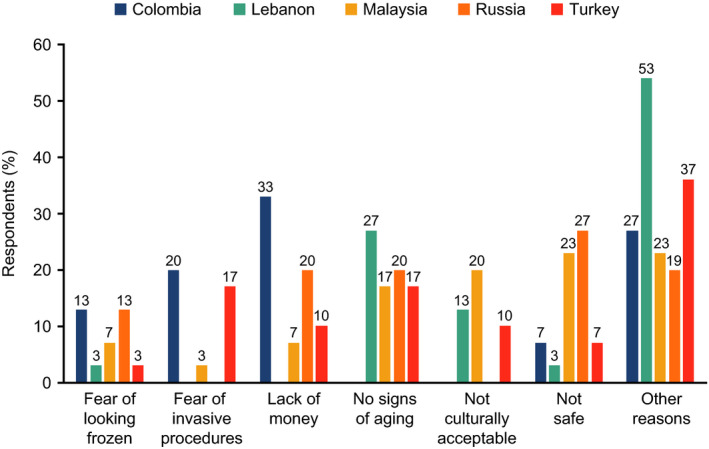

3.1.8. Factors influencing a decision to undergo (or not undergo) an aesthetic medical procedure

The reasons nonusers gave for not undergoing aesthetic medical procedures varied between countries (Figure 3). As with botulinum toxin injections, Malaysian and Russian respondents were more risk adverse, considering safety to be the primary factor for not undergoing a procedure. Lack of money to pay for a procedure was the primary reason for Colombian and secondary reason for Russian respondents but did not feature at all in the reasons given by Lebanese respondents. Cultural lack of acceptability of aesthetic procedures was a factor for up to one‐fifth of respondents from Lebanon, Malaysia, and Turkey but for none of those from Colombia and Russia.

Figure 3.

The primary factor for not undergoing aesthetic medical procedures (nonusers, n = 30 per country). The data correspond to the percentage of respondents agreeing with the indicated statement. Data source: Survey 1

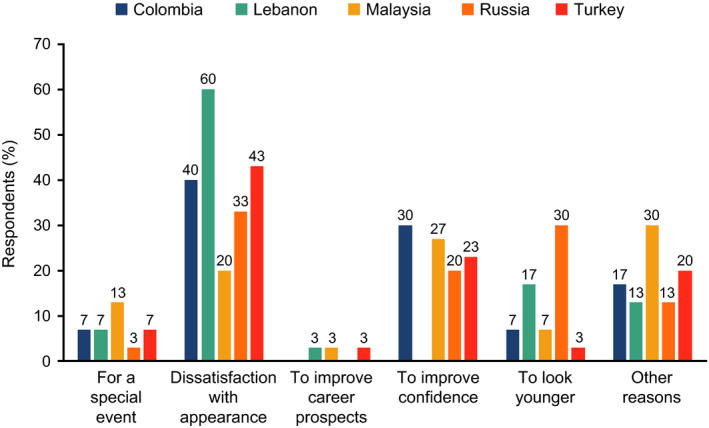

The most influential factor leading to a user's first aesthetic medical procedure was dissatisfaction with appearance in all countries except Malaysia (Figure 4). Improving self‐confidence and looking younger were the other main factors for undergoing an aesthetic medical procedure.

Figure 4.

The prime factor for undergoing the first aesthetic medical procedure (users, n = 30 per country). The data correspond to the percentage of respondents agreeing with the indicated statement. Data source: Survey 1

3.1.9. Expectations and outcomes of aesthetic medical procedures among users

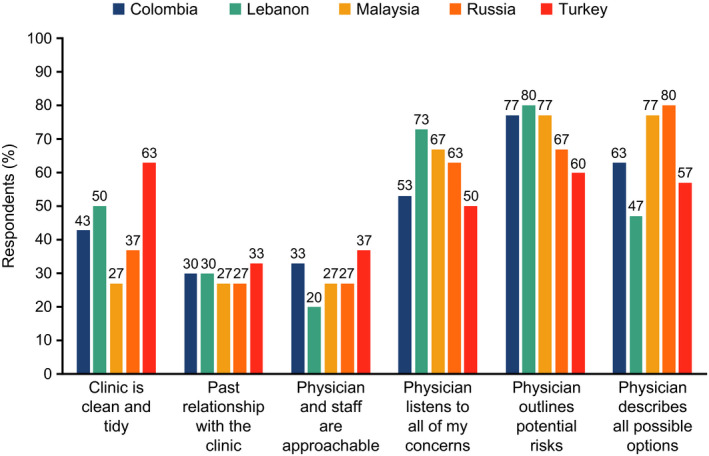

The majority of users in all countries expected the physician to outline potential risks, listen to all concerns and, with the exception of Lebanese respondents, to describe all possible options (Figure 5). A somewhat surprising finding was that it was only in Turkey where most users expected the clinic to be clean and tidy.

Figure 5.

Factors contributing to the overall experience of an aesthetic medical procedure (users, n = 30 per country). The data correspond to the percentage of respondents ranking the feature as one of the three most important. Data source: Survey 1

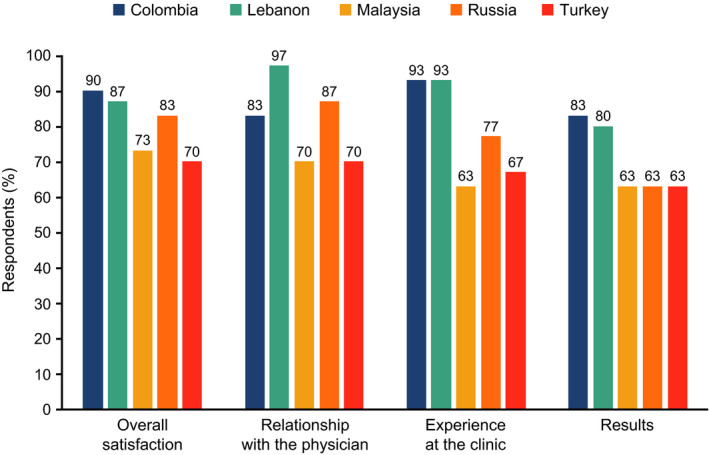

Users were highly satisfied (>60% of respondents in each country) with the relationship with the physician, their experience at the clinic, and the results of the procedure (Figure 6). Overall satisfaction levels ranged from approximately 70% in Turkey to approximately 90% in Colombia, which is suggestive that the expectations of the users were largely met.

Figure 6.

Satisfaction with aspects of aesthetic medical procedures (users, n = 30 per country). The data correspond to the percentage of respondents who were very satisfied or moderately satisfied with the indicated aspect of the procedure. Data source: Survey 1

3.2. Survey 2: Patient expectations and experiences of nonsurgical aesthetic treatment

3.2.1. Characteristics of the study population

A total of 160 respondents completed the questionnaire (Colombia [n = 36], Russia [n = 36], Thailand [n = 27], Turkey [n = 36], UAE [n = 25]). Participants were predominantly women (99%), aged between 35 and 54 years (84%) and from low (42%)‐ or middle (30%)‐ income households. The most frequent nonsurgical aesthetic treatments reported were skin cleansing (71%) and teeth whitening (61%) with a lesser number of participants having undergone laser treatment (47%), hair treatment (40%), skin rejuvenation (39%), expression wrinkle injections (30%), dermal filler injections (24%), or facial reshaping injections (14%). Over two‐thirds of participants (68%) had received at least three types of treatment.

3.2.2. Importance of nonsurgical aesthetic treatment and awareness of procedures

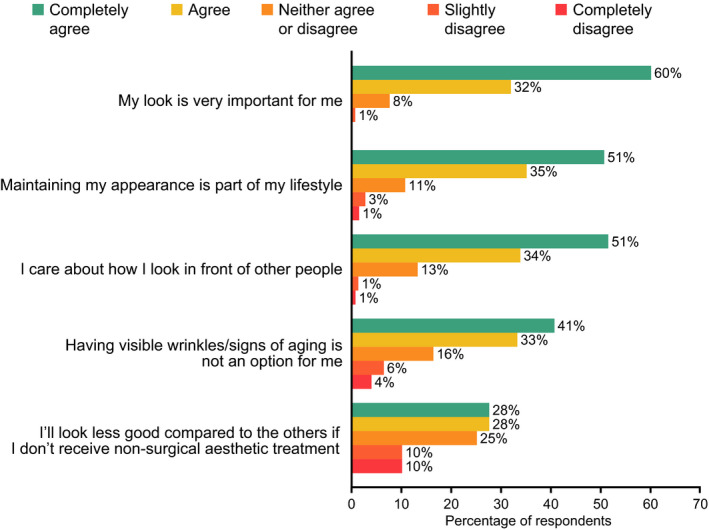

Most respondents stated that how they look is important to them (92%) and that maintaining appearance is part of their lifestyle (86%) (Figure 7). Other areas of importance were how the patient would look to other people (85%) and that they would be less attractive compared with other people if they did not undergo nonsurgical aesthetic treatment (56%).

Figure 7.

Drivers for nonsurgical aesthetic treatment. Data source: Survey 2 (n = 160)

Over half the respondents considered nonsurgical aesthetic treatment to be more important to them than their usual beauty routine (58%) and more effective than diet and exercise in maintaining their appearance (57%). By far, the most important source of information about aesthetic treatments and suitable clinics was a recommendation from a friend or colleague (66%) with Internet searching being stated as being the most important source of information by less than one‐fifth of respondents.

3.2.3. Experiences of nonsurgical aesthetic treatment

Most patients’ initial contact with the clinic was either in person (59%) or by phone (53%), with only a small percentage (4%) using email. There were wide inter‐country variations, with only 28% of Russian respondents initially visiting the clinic compared with over 83% in Turkey and the UAE. In most cases, the patients’ first point of contact was the receptionist (69%), although this was less common in Turkey (39%) compared with other countries (>66%).

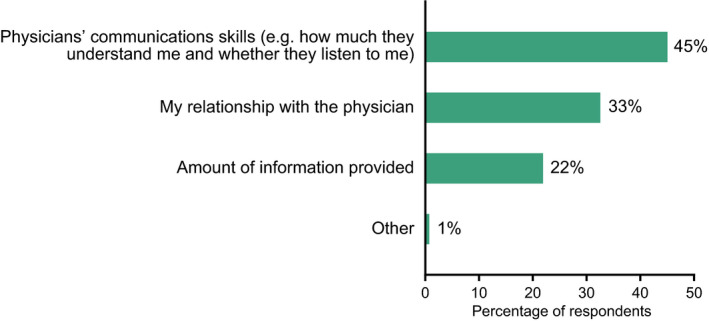

Overall satisfaction with the preconsultation experience was generally good, scoring over 8 out of 10 points in all countries except Thailand (7.5). The amount of information provided was the most important preconsultation factor (39% of respondents) followed by the clinic environment (31%), with well‐informed patients more likely to be satisfied with outcomes. Respondents’ overall satisfaction with the consultation experience scored a mean of 8.5, with the Thai respondents being the least satisfied (mean score of 7.7) and Columbian respondents being most satisfied (mean score of 9.0). While respondents generally felt well informed about the procedure (mean score: 8.6), a considerable percentage of respondents felt they were not provided with sufficient detail (66%) and that too many professional/medical terms were used (41%). The patient‐physician relationship was crucial to the success of the consultation, with 45% of respondents citing the physician's communications skills as being the most important factor for an ideal consultation (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The most important factors in a successful consultation. The data correspond to the percentage of respondents agreeing with the indicated statement. Data source: Survey 2 (n = 160)

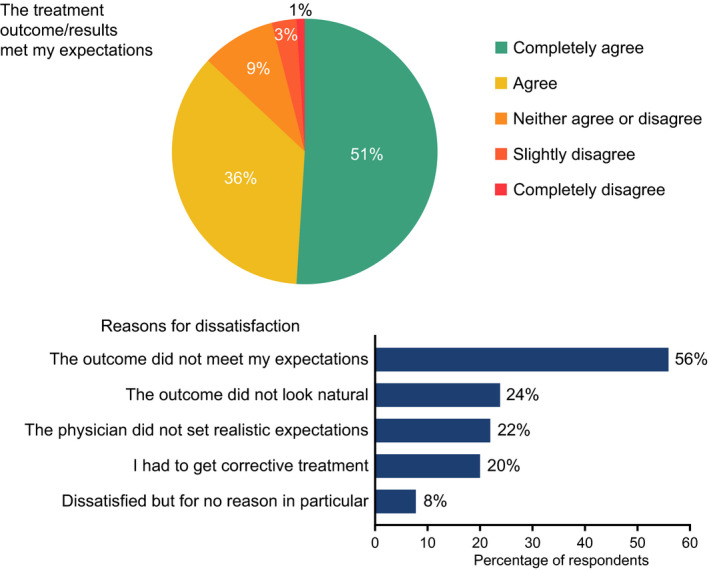

Satisfaction with treatment outcome was good (mean score: 8.2, out of 10) with the lowest mean score, 7.0, reported from Thai respondents. Altogether, 87% of respondents were satisfied with the results (Figure 9) and 67% experienced very little pain or discomfort. However, 47% were disappointed that the results did not last as long as they had hoped. Among those who expressed dissatisfaction the main reason was that the outcome did not meet expectations or did not look natural, with one‐fifth of dissatisfied respondents having to undergo corrective treatment. At least one follow‐up service was offered to 94% of respondents, ranging from a clinic appointment or follow‐up telephone call to information on aftercare and what to expect. Patients offered more follow‐up services tended to be more satisfied.

Figure 9.

Overall satisfaction with treatment and reasons for dissatisfaction. Data source: Survey 2 (n = 160)

3.2.4. Indicators of treatment satisfaction

The most important factors of patient satisfaction were being well informed/provided with sufficient information, being offered a follow‐up appointment and the perception that the treatment offered was not solely for commercial reasons (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Factors determining patient satisfaction with the overall experience. The data correspond to the percentage of respondents satisfied with the outcome or less satisfied with the outcome agreeing with the indicated statement. Data source: Survey 2 (n = 160)

4. DISCUSSION

The two surveys presented here provide a much‐needed insight into aesthetic ideals and expectations, experiences and satisfaction with aesthetic treatments outside Europe and North America, using data gathered from seven different countries. It should be noted that, unlike in some other studies, one of the current surveys included open‐answer questions, which permitted the inclusion of items such as self‐confidence and other personality traits in addition to physical attributes. Respondents in both surveys were predominantly women in their 30s to mid‐50s. As expected, there were differences between country responses, which can be attributed to cultural differences as well as socioeconomic factors. However, the aims of the surveys were not to determine consistencies but to gather a general insight into the perception of nonsurgical aesthetic procedures in novel populations.

In the surveyed countries, eyes and smile were identified as the key aesthetic traits determining beauty in both men and women. For female beauty, respondents preferred smooth skin around the eyes, which may increase the likelihood of women considering periorbital aesthetic medical procedures. This is consistent with findings from studies in Europe and Asia where eyes, along with skin, were commonly regarded as important for facial attractiveness.11, 12, 13 It is interesting that eyes and smile were also featured that most respondents thought were their most beautiful facial feature.

In survey 1, the nose was the main feature that respondents would like to change about themselves, which is broadly in line with a study showing that Turkish women in their 20s and 30s focus on cosmetic procedures for the nose, such as rhinoplasty, and skin.9 However, older women were unhappy with the periorbital area and jawline,9 a finding that is not reflected in the current surveys.

Awareness of various aesthetic procedures was generally high, even among nonusers, which is consistent with previous research in rural women in India14 and professionals in Nigeria15 who showed awareness ≥79%.

Although botulinum toxin procedures were generally considered safe, only <25% of nonusers would consider undertaking such a procedure and <50% of users had previously had such injections. This is probably a reflection of approximately half of participants considering botulinum toxin procedures were not conducive to aging gracefully even though the majority of participants agreed they could help reduce the signs of aging. As might be expected, users of nonsurgical aesthetic procedures were generally more favorable as to the benefits and results of botulinum toxin, although some apparent inconsistencies were observed. For instance, a greater percentage of Turkish users compared with nonusers considered that recipients of botulinum toxin looked fake or had an appearance of a frozen face, while a greater percentage of nonusers compared with users thought that these procedures can help people to age gracefully. The respondent's opinions on or experiences of different botulinum toxin products was not assessed in this survey.

Respondents had a generally positive view of aesthetic medical procedures and had observed favorable changes in both physical appearance and attitude among people using them. This echoes findings that casual observers considered Caucasian women undergoing procedures to look younger and more attractive.16 As expected, perceptions and attitudes were generally more positive among users than nonusers, with nonusers more concerned about the safety and efficacy of treatments. Perceptions of appearance postaesthetic medical procedures showed inter‐country variation, with respondents in Malaysia, Turkey, and Lebanon seeking more subtle differences compared with the marked changes desired in Colombia and Russia.

The key motivator for aesthetic procedures in Saudi Arabian women was reported to be improving self‐esteem,4 which was also a key factor from Malaysian participants in our research, while a study in Taiwanese women also found dissatisfaction with appearance to be a key motivator for undergoing cosmetic procedures,17 which was also seen in our surveys.

A number of different barriers to undergoing an aesthetic procedure were cited in our study including cost, safety concerns, lack of cultural acceptance, and the perception that it was not required. However, key barriers from studies in USA and Europe were fear of a poor result,2 along with anxiety about complications and pain.18 At least part of the variation in attitudes to procedures among East Asian individuals is due to cultural differences, according to a questionnaire study on a group of international college students in Japan,19 reflecting the divergent results presented here.

According to our results, respondents seeking treatment need to feel reassured, and overall satisfaction, the primary outcome criterion in elective aesthetic medical procedures, is driven by four factors: the amount and quality of information received before and during the consultation, the patient‐physician relationship, treatments and services being recommended based on patient need rather than commercial gain, and availability of follow‐up services including allowing patients to stay for a period of observation following the procedure. A good patient‐physician relationship is paramount and could be improved by physicians through listening carefully to patients’ concerns, outlining treatment procedures, presenting all potential risks, and avoiding the use of medical jargon. Although cosmetic surgery does not always lead to patients feeling younger or better about themselves than nonusers of surgery,20 our surveys revealed that most respondents were satisfied with treatment outcomes. However, a considerable number of users were disappointed that the effects were relatively short‐lived or that their expectations were not met, with one‐fifth of users feeling that the physician had misled them. Thus, managing patient expectations before treatment plays an important role in patient satisfaction with treatment.

4.1. Study limitations

Internet‐based surveys are prone to selection bias. There is likely an inherent bias in people who have chosen to pay for procedures that will likely impact on their satisfaction and perception of outcomes. Given that participants had to fill out a screening questionnaire to check that selection criteria were met, it may be that only highly motivated participants completed this stage and thus our surveys did not represent a typical population. The anonymity and self‐reporting aspects of the survey may have introduced additional bias and procedures not performed recently may be subjected to recall bias. Another limitation is that neither questionnaire had been psychometrically validated. In addition, for survey 1, investigation of the ideal facial aesthetic was relatively simplistic and did not include analytical parameters, such as facial fluctuating asymmetry, facial averageness, facial sexual dimorphism, facial maturity, or other morphometric parameters.21, 22

5. CONCLUSION

In an observational survey performed in adults in five countries worldwide (Colombia, Lebanon, Malaysia, Russia, and Turkey), the eyes and smile were the most important aspects of beauty in both men and women. In this and another observational survey (including Thailand and the UAE, but not including Lebanon and Malaysia), there was good awareness of aesthetic medical procedures and the main drivers to seeking out treatment were a dissatisfaction with appearance or a desire to improve confidence or maintain attractiveness. Being well informed, having a good patient‐physician relationship and managing expectations were key to maximizing satisfaction with procedures.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Alessio Redaelli received consultancy fees from Ipsen. Sana Siddiqui Syed is a salaried employee of Decision Resources Group. Xierong Liu was a salaried employee of Opinion Health at the time the research was performed. Michele Poliziani is a salaried employee of Opinion Health. Inna Prygova is a salaried employee of Ipsen. Vasiliy Atamanov is a certified trainer for Ipsen Russia. Hakan Erbil has nothing to disclose.

Supporting information

Supinfo

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Study procedures for survey 1 and survey 2 were managed by Decision Resources Group and Opinion Health, respectively. The authors thank all respondents involved in this survey: Medical writing support; The authors thank Watermeadow Medical, an Ashfield company, for providing medical writing and editorial support, which was sponsored by Ipsen in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines.

Redaelli A, Siddiqui Syed S, Liu X, et al. Two multinational, observational surveys investigating perceptions of beauty and attitudes and experiences relating to aesthetic medical procedures. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19:3020–3031. 10.1111/jocd.13349

Funding information

These studies were funded by Ipsen Pharma (Boulogne‐Billancourt, France).

REFERENCES

- 1. Lockenhoff CE, De Fruyt F, Terracciano A, et al. Perceptions of aging across 26 cultures and their culture‐level associates. Psychol Aging. 2009;24(4):941‐954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galanis C, Sanchez IS, Roostaeian J, Crisera C. Factors influencing patient interest in plastic surgery and the process of selecting a surgeon. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(4):585‐590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mousavi SR. The ethics of aesthetic surgery. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010;3(1):38‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al‐Natour SH. Motives for cosmetic procedures in Saudi women. Skinmed. 2014;12(3):150‐153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Postma E. A relationship between attractiveness and performance in professional cyclists. Biol Lett. 2014;10(2):20130966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Talamas SN, Mavor KI, Perrett DI. Blinded by beauty: attractiveness bias and accurate perceptions of academic performance. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0148284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Honigman RJ, Phillips KA, Castle DJ. A review of psychosocial outcomes for patients seeking cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(4):1229‐1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lazar CC, Deneuve S. Patients' perceptions of cosmetic surgery at a time of globalization, medical consumerism, and mass media culture: a French experience. Aesthet Surg J. 2013;33(6):878‐885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sezgin B, Findikcioglu K, Kaya B, Sibar S, Yavuzer R. Mirror on the wall: a study of women's perception of facial features as they age. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32(4):421‐425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heidekrueger PI, Juran S, Ehrl D, Aung T, Tanna N, Broer PN. Global aesthetic surgery statistics: a closer look. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2017;51(4):270‐274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ehlinger‐Martin A, Cohen‐Letessier A, Taieb M, Azoulay E, du Crest D. Women's attitudes to beauty, aging, and the place of cosmetic procedures: insights from the QUEST Observatory. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15(1):89‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liew S, Wu WT, Chan HH, et al. Consensus on changing trends, attitudes, and concepts of Asian beauty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2016;40(2):193‐201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rhee SC, An SJ, Hwang R. Contemporary Koreans' perceptions of facial beauty. Arch Plast Surg. 2017;44(5):390‐399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patil SB, Kale SM, Khare N, Jaiswal S, Ingole S. Aesthetic surgery: expanding horizons: concepts, desires, and fears of rural women in central India. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2011;35(5):717‐723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Adeyemo WL, Mofikoya BO, Bamgbose BO. Knowledge and perceptions of facial plastic surgery among a selected group of professionals in Lagos, Nigeria. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(4):578‐582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bater KL, Ishii LE, Papel ID, et al. Association between facial rejuvenation and observer ratings of youth, attractiveness, success, and health. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2017;19(5):360‐367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen HC, Karri V, Yu RL, Chung KP, Lu YT, Yang MC. Psychological profile of Taiwanese female cosmetic surgery candidates: understanding their motivation for cosmetic surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34(3):340‐349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leitermann M, Hoffmann K, Kasten E. What's preventing us to get more attraction: the fear of aesthetic surgery. World J Plast Surg. 2016;5(3):226‐235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghotbi N, Khalili M. Cultural values influence the attitude of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean college students towards cosmetic surgery. Asian Bioeth Rev. 2017;9(1–2):103‐116. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eriksen SJ. To cut or not to cut: cosmetic surgery usage and women's age‐related experiences. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2012;74(1):1‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Munoz‐Reyes JA, Iglesias‐Julios M, Pita M, Turiegano E. Facial features: what women perceive as attractive and what men consider attractive. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0132979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pothanikat JJ, Balakrishna R, Mahendra P, Neeta J. Two‐dimensional morphometric analysis of young Asian females to determine attractiveness. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2015;5(2):208‐212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supinfo