ABSTRACT

Background

Medical students internationally have volunteered and stepped up to support frontline clinical teams during the COVID-19 pandemic. We know very little about the motivation of those volunteering, or their concerns in deploying to a new role. We aim to establish the reasons that medical students volunteered in one Trust and understand to their concerns.

Methods

Structured survey, thematic analysis and categorisation of volunteer student perceptions.

Results

Medical students volunteered for broadly four reasons: to make a contribution, to learn, to benefit from remuneration and for an activity during the national lockdown. There were disparate concerns; however, the most common involved availability of personal protective equipment, uncertainty as to expectations and becoming infected.

Conclusions

We must recognise and applaud the motivations of our future workforce who have stepped up to support the NHS at a time of unprecedented demand. The experiences and learning gained during this period will undoubtedly shape their future medical training and careers.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, medical education

Introduction

Managing the COVID-19 pandemic has placed an unprecedented burden on healthcare organisations and the limited existing resources available, including clinical staff.1 The UK government and NHS England have responded to this challenge by increasing availability of acute beds in existing hospitals, prioritising urgent and emergency work and opening the new NHS Nightingale hospitals.2 These changes are in the context of additional workforce challenges consequent to either the direct illness of healthcare workers or self-isolation due to illness of household members. Many initiatives have been launched to address these workforce challenges, for example asking recently retired staff to return to clinical practice.3 Significant numbers of medical students have also stepped forward, volunteering to provide support in clinical environments. Medical schools worked rapidly over a 2-week period to support the provision of medical student volunteers to help on the clinical ‘front line’.4

Medical student volunteers offer a vital asset in combating the COVID-19 pandemic. It is however important to note that they are not fully trained or qualified doctors, and will be working in often unfamiliar environments, with significant unknowns around their own roles and the future development of this pandemic. In this article we look to better understand the reasons these students volunteered to support on the clinical frontline, alongside their concerns and anxieties about stepping into such a situation. By understanding why students volunteer and by understanding their concerns we are better able to recognise their contribution, deploy them most effectively and support them in their new roles. Undoubtedly their experiences will shape both their future medical school training and future medical careers and we need to rapidly understand what those implications may be and how best to support these courageous volunteers both now and into the future.

Method

All medical students from the University of Warwick Medical School (WMS) who volunteered to support clinical teams at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) NHS Trust were included in the study. UHCW is a major 1,264-bed tertiary referral centre in the West Midlands region that usually employs in excess of 9,000 staff. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, UHCW requested support from medical students from WMS when it was becoming evident that the substantive workforce was becoming denuded due to staff illness or self-isolation. WMS is a graduate entry medical school, also in the West Midlands region. The graduate entry course is a 4-year course, with the first year being non-clinical and subsequent years having a clinical focus. 132 students volunteered to support clinical teams at UHCW during the COVID-19 pandemic. These students were deployed across departments within the hospital, working between 24 and 37.5 hours per week and paid at Band 3 (years 1–3) and Band 4 (year 4) level on the NHS Agenda for Change (AfC) pay scales (circa £20,000–£25,000 per annum).

An electronic survey was distributed to all volunteer medical students on attending their induction at UHCW NHS Trust. The survey questions are given in Box 1. The survey was piloted on a small number of medical education staff members before dissemination. These survey questions were designed to be generalised survey questions that would facilitate free-text responses suitable for subsequent qualitative analysis. Qualitative analysis was felt to be the best approach to survey design because of the novel nature of this unprecedented recruitment during the COVID-19 pandemic and the lack of existing knowledge regarding medical student perceptions. A free-text qualitative survey approach allows the medical students to express a broad range of perceptions and expand on these as relevant. An anonymous survey was felt to be preferable to qualitative interviews in allowing the students to freely express any deep-seated concerns, for example around becoming infected themselves. This approach was also appropriate given the limited resource available during the COVID-19 pandemic, while meeting the urgent need to identify student concerns and mitigate them where possible.

Box 1.

Electronic survey questions

| 1 | What medical school year are you in? |

| 2 | Why did you decide to come and volunteer at UHCW? |

| 3 | Do you have any concerns/worries about working at the hospital? |

| 4 | How could these be addressed? |

Survey responses were collated electronically and analysed anonymously. Independent two-author analysis of the qualitative responses was performed through thematic analysis and subsequent categorisation. Definition of the final categories was performed in collaboration with a third author. The methodological approach facilitated remote working where possible alongside appropriate social distancing following UK government advice.

Results

There were 132 responses to the survey from 132 students who attended the induction, giving a response rate of 100%. In addition to the 132 students allocated to the University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust site, an additional 123 students volunteered and were allocated to smaller district general hospitals in the region, but were not included in the study. Responses by medical school year are shown in Table 1; there were four responses which did not include an allocated medical school year. All respondents explained the reasoning for volunteering to support the Trust. 27 respondents (20%) did not enter any information in response to the questions regarding concerns/addressing those concerns. The total narrative for qualitative evaluation was 4,426 words.

Table 1.

Number of responses per medical school year

| Medical school year | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| 1 | 16 |

| 2 | 34 |

| 3 | 71 |

| 4 | 11 |

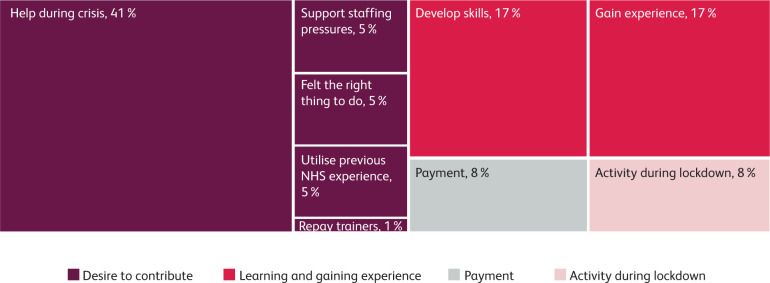

Thematic analysis and categorisation of the responses querying why students decided to volunteer resulted in four over-arching themes: desire to contribute; wish to learn and gain experience; payment; and the desire to have an activity to undertake during lockdown. These overarching themes were further subdivided into the sub-themes displayed in Fig 1. The desire to contribute was the most commonly cited reason for volunteering, and where multiple reasons were given this was almost universally given as the primary reason. Within this category there was a common description of ‘duty’, with 10 respondents (7%) using the word specifically and many others strongly alluding to the concept with phrasing such as ‘moral responsibility,’ ‘do my bit’ and ‘I feel that it is morally the right thing to do.’ Many wanted to repay the organisation and staff for training them to date and many saw the opportunity as a means to gain valuable clinical experience at a time of government-mandated population-level social restrictions and lockdown.

Fig 1.

Main themes and subthemes in reasons given by medical students for volunteering.

There was similarity across medical school years regarding the reason for volunteering being primarily to support clinical teams; however, there was a greater focus on learning and maintaining skills among final (fourth year) medical students who would shortly be beginning their foundation year 1 role and working formally as junior doctors in the UK.

Responses regarding concerns about starting the new clinical role, and potential solutions, were much more disparate. The most commonly raised concerns were around availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) (22%), uncertainty of what exactly their role would entail (16%) and fears about becoming infected themselves with COVID-19 (12%). The risk of infection was discussed as a personal risk, as a risk to family members or other household members and was also associated with the risk of dying from the COVID-19, with recent media reports of healthcare professionals dying due to COVID-19. Table 2 shows the breakdown of concerns the volunteer medical students had before commencing their roles.

Table 2.

Concerns and anxieties regarding working at University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire

| Concern | Total |

|---|---|

| Lack of PPE | 28 |

| Uncertainty about role/unclear expectations | 21 |

| Get/pass on COVID-19 | 15 |

| Not needed/getting in way | 12 |

| Inadequate support/supervision | 10 |

| Competency/limits | 9 |

| Uniform/clothing | 7 |

| Hours/shifts | 6 |

| Lack of experience/ability | 4 |

| See something traumatic | 3 |

| Refresher needed for clinical skills | 3 |

| Coping with stress/pressure | 3 |

| Travel/moving out | 2 |

| Poor communication from trusts | 2 |

| Skills/knowledge not used | 2 |

| Uncomfortable situation | 2 |

Discussion

This research demonstrates that altruism was the primary reason medical students in this setting volunteered to help support the clinical front line during the COVID-19 pandemic, with students feeling a strong sense of duty to support both patient needs and healthcare staff under pressure. This altruistic behaviour was demonstrated despite significant concerns regarding not being provided with appropriate PPE to protect themselves from infection, serious illness and possible death, alongside significant uncertainties regarding the role and what was to come. The students exhibited significant professionalism, looking to maintain and broaden their clinical skills by volunteering at a time when otherwise, most of their conventional university study and learning was placed on hold. The need to continue learning was particularly important for final year medical students who would soon be seeing patients in practice themselves. Students described uncertainty about their roles in the clinical environment; this is unsurprising given this was a new and unprecedented experience. It is essential that we salute and mark the determination, dedication and altruistic behaviour of these medical students stepping up to support the health system at an unprecedented and challenging time. Simultaneously, it is imperative that clarity of role and purpose, support and supervision are provided to clinical volunteers in order to ensure volunteering during the pandemic is a learning opportunity.

We must not underestimate the concerns of volunteers, however. This study highlighted what those concerns are and what needs to be addressed, either in terms of reassurance at induction or by practical means. Logistical challenges were described relating to appropriate clothing/uniform and travel arrangements, which had become significantly more difficult during the pandemic. Access to PPE was a concern, fuelled by enhanced media interest. It is important to ensure that access to uniforms, appropriate clothing and appropriate PPE is addressed at the outset for a clinical volunteer cohort. The risk of contagion, ill-health, transmission and death were all linked to concerns about role and protection. It is important that these concerns are openly discussed at induction and that training is provided to ensure risks are mitigated as much as possible by providing hands-on training in handwashing techniques, ‘donning and doffing’ of PPE and other specific procedures and techniques relevant to areas of placement.

Remuneration as a driver was an interesting phenomenon to comprehend. As graduate-entry medical students, many in this cohort have accumulated significant student debt and some students have been accustomed to generating income from tutoring or other employment. The COVID-19 pandemic curtailed the opportunities to earn such income and it is therefore appropriate that students receive appropriate payment for the services they provide, despite remuneration not being the primary driver for volunteering.

The implications of this pandemic-related clinical volunteering experience will be long-lasting. This future workforce will enter clinical practice with experiences not acquired by their predecessors. Some of the experiences will be positive, others negative. The psychological impact is something students themselves have raised concerns about. They will require careful support both during and after the pandemic. There may be variation in the career paths of trainees consequent to their experience.

The phenomenon of volunteering and the challenges described are not local or national, but rather international changes in medical practice and training. A perspective paper considering both medical student and trainee perceptions in the United States revealed similar challenges and motivations. Importantly the paper highlighted that the COVID-19 pandemic is a ‘teachable moment’.5

This study represents the first of its kind to consider the reasons, perceptions and challenges described by medical students in the UK as they step up to meet the challenge created by the COVID-19 pandemic. The study benefits from a large number of respondents, a high response rate and an opportunity for anonymous free text responses from students. Limitations include the single clinical site and single cohort of graduate-entry medical students. This is important as graduate entry students tend to be older and have greater family commitments and wider life experiences. Despite this, we believe that the results are transferable across other medical students in the UK. We do not think there is any reason to believe the altruistic and dedicated behaviour shown by the graduate entry students in this cohort would be different to an undergraduate or mixed undergraduate/postgraduate setting.

Future research and follow-up will undoubtedly be valuable to understand how these trainees experienced the COVID-19 pandemic in the diverse clinical roles they delivered, what support they need following such experiences and how this will change their future learning, practice and career choices. It is important to note that not all students volunteered to participate in the programme, and 20 students were unable to start the programme initially due to the need to re-sit examinations. There were also a small number of students who volunteered later in the programme and were not included in the initial assessment of perceptions. Additionally, some students were at increased risk and required to shield or minimise clinical exposure during the high-risk period. While this study focuses on those who did volunteer to participate in the scheme, further work could consider those who declined to participate and the subsequent differential impact on learning, education and training. Given the very large number who did volunteer to participate in the programme, however, and the positive altruistic characteristics described, we would propose that such an approach needs to be coordinated nationally, with input from Health Education England, the General Medical Council and the Medical Schools Council.

Conclusions

The medical students volunteering into employed roles to support the NHS in a time of unprecedented need have shown truly commendable resolve, altruism and dedication. As the future medical workforce this is both reassuring and humbling. This resolve is shared by a wide range of other staff groups and professionals who have stepped up to provide much needed support across the NHS and healthcare services internationally. We must recognise such dedication and ensure we provide appropriate support, advice, training and protection both throughout the current emergency and their future careers.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to recognise and acknowledge the considerable courage and determination shown by the medical student cohort in volunteering to support the front line, and similarly all those in medical education and support roles who have enabled this process.

References

- 1.Adams JG, Walls RM. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA 2020;323:1439–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rimmer A. Sixty seconds on... nightingales. BMJ 2020;368:m1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahase E. Covid-19: UK could delay non-urgent care and call doctors back from leave and retirement. BMJ 2020;368:m854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahase E. Covid-19: medical students to be employed by NHS as part of epidemic response. BMJ 2020;368:m1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gallagher TH, Schleyer AM. ‘We signed up for this!’ – student and trainee responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]