Abstract

We presented complete chloroplast genome of Prince Ginseng, Pseudostellaria heterophylla which is 149,795 bp long and has four subregions: 81,460 bp of large single copy (LSC) and 16,983 bp of small single copy (SSC) regions are separated by 25,676 bp of inverted repeat (IR) regions including 126 genes (81 CDS, 8 rRNAs, and 37 tRNAs). The overall GC content of the chloroplast genome is 36.5% and those in the LSC, SSC, and IR regions are 34.3%, 29.4%, and 42.3%, respectively. Phylogenetic trees of 25 Caryophyllaceae species present phylogenetic position of P. heterophylla among available Pseudostellaria species.

Keywords: Pseudostellaria, chloroplast genome, Pseudostellaria heterophylla, clade I, Caryophyllaceae

Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax (Caryophyllaceae) is a perennial herb widely distributed in north-eastern Asia and its roots are used as medicinal plants in Korea and China. Pseudostellaria heterophylla contains many useful chemical compounds or peptides including pseudostellarins (Morita, Kayashita, Takeya, et al. 1994; Morita, Kobata, et al. 1994; Morita, Kayashita, Kobata, et al. 1994a, 1994b; Morita, Kayashita, Takeya, Itokawa 1995; Morita, Kayashita, Takeya, Itokawa, Shira 1995; Han et al. 2007), Kunitz-type trypsin inhibitor, novel lectin (Wang and Ng 2006), and antitumor polysaccharides (Wong et al. 1994). P. heterophylla has been studied for floral ontogeny and gene regulatory of dimorphic cleistogamy, which is a mixed mating system having both chasmogamous and cleistogamous flowers (Luo et al. 2012; 2016). P. heterophylla belongs to clade I of Pseudostellaria genus (Zhang et al. 2017) containing P. longipedicellata, P. palibiniana, and P. okamotoi (Kim et al. 2018; Kim, Heo, Lee, et al. 2019; Kim, Heo, Park 2019; Kim and Park 2019).

We sequenced complete chloroplast genome sequence of P. heterophylla collected in Geojedo Island, Geoje-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, Korea (Voucher in InfoBoss Cyber Herbarium; Y. Kim, IB-00063). Total DNA was extracted from fresh leaves of P. heterophylla by using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Genome sequencing was performed using HiSeqX at Macrogen Inc., Korea, and de novo assembly and base confirmation were done by Velvet 1.2.10 (Zerbino and Birney 2008), SOAPGapCloser 1.12 (Zhao et al. 2011), BWA 0.7.17 (Li 2013), and SAMtools 1.9 (Li et al. 2009). Geneious R11 11.0.5 (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand) was used for chloroplast genome annotation based on P. longipedicellata (NC_039454; Kim et al. 2018).

The chloroplast genome of P. heterophylla (Genbank accession is MK801111) is 149,795 bp long (GC ratio is 36.5%) and has four subregions: 81,460 bp of large single copy (LSC; 34.3%) and 16,983 bp of small single copy (SSC; 29.4%) regions are separated by 25,676 bp of inverted repeat (IR; 42.3%). LSC and SSC are longer than those of three Pseudostellaria species; while IR is shorter than those of three Pseudostellaria species. It contains 126 genes (81 protein-coding genes, 8 rRNAs, and 37 tRNAs); 18 genes (7 protein-coding genes, 4 rRNAs and 7 tRNAs) are duplicated in IR regions. Its SSC is inverted comparing with other Pseudostellaria chloroplast genomes like Salix koriyanagi (doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1602012), Salix gracilistyla (Park et al., in submission ), and Hibiscus syriacus (Kim, Oh, et al. 2019).

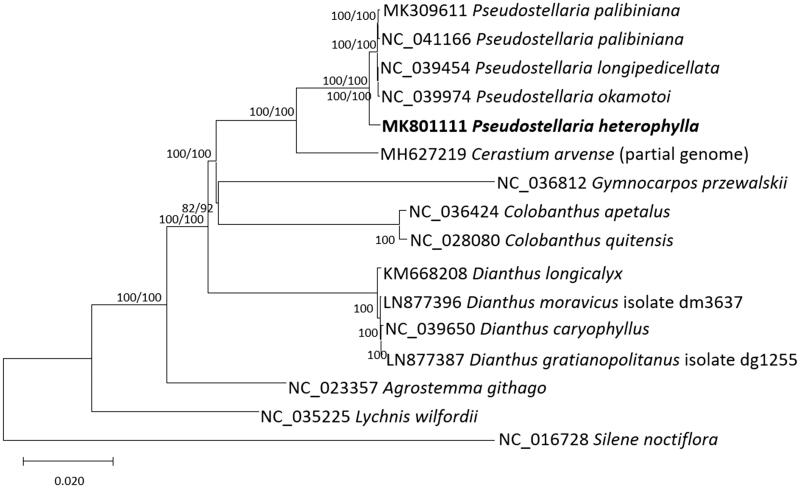

Sixteen Caryophyllaceae complete chloroplast genomes were aligned by MAFFT 7.388 (Katoh and Standley 2013) with rearranging SSC sequences of Colobanthus apetalus (Androsiuk et al. 2018) and P. heterophylla for constructing bootstrapped neighbor joining and maximum likelihood trees using MEGA X (Kumar et al. 2018). Phylogenetic trees show that P. heterophylla is located outside of four Pseudostellaria chloroplast genomes, congruent with previous phylogeny (Zhang et al. 2017; Figure 1). Moreover, Cerastium was also positioned outside of Pseudostellaria clade with a relatively long branch (Figure 1), presenting a lack of taxa between Cerastium and Pseudostellaria. With additional chloroplast genomes of the species between Cerastium and Pseudostellaria, such as Stellaria, it contributes understanding of Pseudostellaria phylogeny in detail.

Figure 1.

Neighbor joining (bootstrap repeat is 10,000) and maximum likelihood (bootstrap repeat is 1,000) phylogenetic trees of sixteen Caryophyllaceae complete chloroplast genomes: Pseudostellaria heterophylla (MK801111, in this study), Pseudostellaria longipedicellata (NC_039454), Pseudostellaria okamotoi (NC_039974), Pseudostellaria palibiniana (NC_041166 and MK309611), Cerastium arvense (MH627219; partial genome), Gymnocarpos przewalskii (NC_036812), Colobanthus apetalus (NC_036424), Colobanthus quitensis (NC_028080), Dianthus longicalyx (KM668208), Dianthus moravicus (LN877396), Dianthus caryophyllus (NC_039650), Dianthus gratianopolitanus (LN877387), Agrostemma githago (NC_023357), Lychnis wilfordii (NC_035225), and Silene noctiflora (NC_016728). Phylogenetic tree was drawn based on neighbor joining tree. The numbers above branches indicate bootstrap support values of neighbor joining and maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees, respectively.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Androsiuk P, Jastrzębski JP, Paukszto Ł, Okorski A, Pszczółkowska A, Chwedorzewska KJ, Koc J, Górecki R, Giełwanowska I. 2018. The complete chloroplast genome of Colobanthus apetalus (Labill.) Druce: genome organization and comparison with related species. PeerJ. 6:e4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Chen J, Liu J, Lee F-C, Wang X. 2007. Isolation and purification of Pseudostellarin B (cyclic peptide) from Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax by high-speed counter-current chromatography. Talanta. 71:801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability . Mol Biol Evol. 30:772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Heo K-I, Lee S, Park J. 2018. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of the Pseudostellaria longipedicellata S. Lee, K. Heo & SC Kim (Caryophyllaceae). Mitochondr DNA B. 3:1296–1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Heo K-I, Lee S, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pseudostellaria palibiniana (Takeda) Ohwi (Caryophyllaceae). Mitochondr DNA B. 4:973–974. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Heo K-I, Park J. 2019. The second complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pseudostellaria palibiniana (Takeda) Ohwi (Caryophyllaceae): intraspecies variations based on geographical distribution. Mitochondr DNA B. 4:1310–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Oh YJ, Han KY, Kim GH, Ko J, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Hibicus syriacus L.‘Mamonde’(Malvaceae). Mitochondr DNA B. 4:558–559. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Park J. 2019. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of the Pseudostellaria okamotoi Ohwi (Caryophyllaceae). Mitochondr DNA B. 4:174–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 35:1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25:2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv Preprint arXiv. 13033997. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Bian F-H, Luo Y-B. 2012. Different patterns of floral ontogeny in dimorphic flowers of Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Caryophyllaceae). Int J Plant Sci. 173:150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Hu J-Y, Li L, Luo Y-L, Wang P-F, Song B-H. 2016. Genome-wide analysis of gene expression reveals gene regulatory networks that regulate chasmogamous and cleistogamous flowering in Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Caryophyllaceae). BMC Genomics. 17:382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Kayashita T, Kobata H, Gonda A, Takeya K, Itokawa H. 1994a. Pseudostellarins A-C, new tyrosinase inhibitory cyclic peptides from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Tetrahedron. 50:6797–6804. [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Kayashita T, Kobata H, Gonda A, Takeya K, Itokawa H. 1994b. Pseudostellarins D-F, new tyrosinase inhibitory cyclic peptides from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Tetrahedron. 50:9975–9982. [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Kayashita T, Takeya K, Itokawa H. 1994. Conformational analysis of a tyrosinase inhibitory cyclic pentapeptide, pseudostellarin A, from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Tetrahedron. 50:12599–12608. [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Kayashita T, Takeya K, Itokawa H. 1995. Cyclic peptides from higher plants, part 15. Pseudostellarin H, a new cyclic octapeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. J Nat Prod. 58:943–947.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Kayashita T, Takeya K, Itokawa H, Shiro M. 1995. Crystal and solution forms of a cyclic heptapeptide, pseudostellarin D1. Tetrahedron. 51:12539–12548. [Google Scholar]

- Morita H, Kobata H, Takeya K, Itokawa H. 1994. Pseudostellarin G, a new tyrosinase inhibitory cyclic octapeptide from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Tetrahedron Letters. 35:3563–3564. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Ng T. 2006. Concurrent isolation of a Kunitz-type trypsin inhibitor with antifungal activity and a novel lectin from Pseudostellaria heterophylla roots. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 342:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C, Leung K, Fung K, Choy Y. 1994. The immunostimulating activities of anti-tumor polysaccharides from Pseudostellaria heterophylla. Immunopharmacology. 28:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. 2008. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18:821–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M-L, Zeng X-Q, Li C, Sanderson SC, Byalt VV, Lei Y. 2017. Molecular phylogenetic analysis and character evolution in Pseudostellaria (Caryophyllaceae) and description of a new genus, Hartmaniella, in North America. Bot J Linnean Soc. 184:444–456. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q-Y, Wang Y, Kong Y-M, Luo D, Li X, Hao P. 2011. Optimizing de novo transcriptome assembly from short-read RNA-Seq data: a comparative study. BMC Bioinformatics. 12:S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]