Abstract

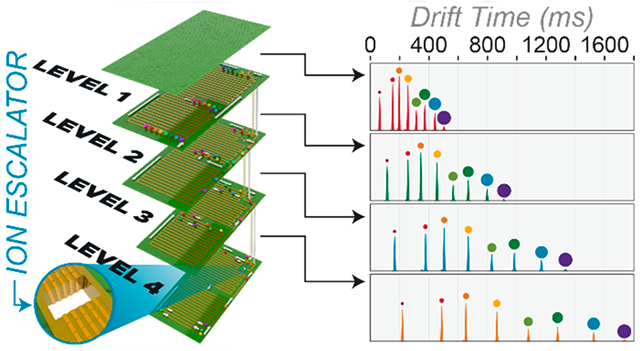

Over the past few years, structures for lossless ion manipulations (SLIM) have used traveling waves (TWs) to move ions over long serpentine paths that can be further lengthened by routing the ions through multiple passages of the same path. Such SLIM “multipass” separations provide unprecedentedly high ion mobility resolving powers but are ultimately limited in their ion mobility range because of the range of mobilities spanned in a single pass; that is, higher mobility ions ultimately “overtake” and “lap” lower mobility ions that have experienced fewer passes, convoluting their arrival time distribution at the detector. To achieve ultrahigh resolution separations over broader mobility ranges, we have developed a new multilevel SLIM possessing multiple stacked serpentine paths. Ions are transferred between SLIM levels through apertures (or ion escalators) in the SLIM surfaces. The initial multilevel SLIM module incorporates four levels and three interlevel ion escalator passages, providing a total path length of 43.2 m. Using the full path length and helium buffer gas, high resolution separations were achieved for Agilent tuning mixture phosphazene ions over a broad mobility range (K0 ≈ 3.0 to 1.2 cm2/(V*s)). High sensitivity was achieved using “in-SLIM” ion accumulation over an extended trapping region of the first SLIM level. High transmission efficiency of ions over a broad mobility range (e.g., K0 ≈ 3.0 to 1.67 cm2/(V*s)) was achieved, with transmission efficiency rolling off for the lower mobility ions (e.g., K0 ≈ 1.2 cm2/(V*s)). Resolving powers of up to ~560 were achieved using all four ion levels to separate reverse peptides (SDGRG1+ and GRGDS1+). A complex mixture of phosphopeptides showed similar coverage could be achieved using one or all four SLIM levels, and doubly charged phosphosite isomers not significantly separated using one SLIM level were well resolved when four levels were used. The new multilevel SLIM technology thus enables wider mobility range ultrahigh-resolution ion mobility separations and expands on the ability of SLIM to obtain improved separations of complex mixtures with high sensitivity.

Graphical Abstract

Ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) is routinely used for rapid separations of gas-phase ions based on size, shape, charge, and interactions with a neutral buffer gas under low E/N conditions (E is the electric field and N is the number density).1,2 The emergence of high resolution ion mobility spectrometers is increasingly revolutionizing the analysis of complex biological mixtures by augmenting mass spectrometry with a fast separation dimension, providing increased peak capacities and high sensitivity.3

Ultrahigh resolution IMS has been defined as a resolving power (Rp) of over 200, measured as the ratio of an ion’s drift time (td) at the peak center to its peak width measured at half height (fwhm)3,4

| (1) |

Several IMS technologies can now achieve such ultrahigh resolution, including in some cases drift tube ion mobility spectrometry (DTIMS),5 trapped ion mobility spectrometry (TIMS),6 and traveling wave ion mobility spectrometry (TWIMS),7 and the continuous ion introduction method differential mobility spectrometry/high field asymmetric waveform ion mobility (DMS/FAIMS).5,8 Generally, ultrahigh resolution has been obtained by optimizing one or more of the following experimental parameters: (1) electric field strength, (2) ion path length, and (3) pressure. Increasing electric field strength is a simple way to increase resolution, but practical limitations (including voltage constraints and ion activation) preclude this approach in many cases. Increasing ion path lengths provide another route to improving resolution; for example, in DTIMS it generally scales with the square root of path length.9-12 However, maximum lengths are generally limited in DTIMS by maximum voltage and practical footprint limitations. Similarly, effective path length can be increased by providing a counter flow of gas to hold ions in place against an electric field gradient, such as in TIMS, but the maximum resolution is limited by practical considerations, including ion volume (saturation limit), slow scan rates (i.e., lower signal), and narrow mobility range (e.g., due to small voltage ramp range).6,13 The use of higher pressures and the potential increase in resolution obtainable due to increased collisional frequency is constrained by both voltage limitations and losses due to the current inability to effectively confine ions at elevated pressures (>~10 Torr). We also note that buffer gas composition3 can be used for specific applications in FAIMS to increase resolving power, but ultrahigh resolution with FAIMS is presently only achieved in conjunction with large ion losses.14

Structures for lossless ion manipulations (SLIM) based upon the use of traveling waves (TW) have achieved some of the highest IMS resolving powers to date.15,16 SLIM utilize two mirror image surfaces incorporating electrode arrays fabricated using printed circuit board (PCB) technology.10,17 SLIM use TWs to propel ions through a separation path in conjunction with RF confinement between the SLIM surfaces and a DC “guard” potential to provide lateral confinement (i.e., orthogonal to the ion path). Such TW-based separations are attractive as the applied voltages are independent of path length and, therefore, avoid voltage breakdown limitations incurred with longer path DTIMS. Initial SLIM designs have incorporated path lengths of up to 16 m, with the maximum path lengths primarily limited by the practical constraints in PCB fabrication (e.g., the accuracy of electrode location and spacing).

The ion path length limitations noted above can be circumvented in DTIMS, TWIMS, and SLIM by the use of ion cycling (or “multipass”) separations, in which ions traverse a given ion path more than once. Such an approach was first reported by Clemmer and co-workers in the context of DTIMS,9 and more recently for both TWIMS (by Waters in a 1 m cyclic arrangement)12 and by our laboratory utilizing the serpentine long path arrangement in SLIM,11 both of which achieve higher resolving powers than their conventional counterparts.1,7,9,12 Specifically, the serpentine ultralong path with extended routing (SUPER) SLIM cycles ions through a 13-m serpentine ion path multiple times, achieving path lengths of kilometers and resolving powers of up to ~1860.11 However, the mobility ranges of multipass separations inevitably become constrained as the number of passes increases due to higher mobility ions overtaking lower mobility ions from a previous pass, which causes increasingly convoluted results. Obtaining ultrahigh resolution over a wide mobility range remains an analytical challenge.

To address this challenge using SLIM, a “multilevel” approach to increasing IMS resolution would in principle increase path lengths by a factor of the number of levels. In such designs, ions would traverse the extended path on one level and then be transferred to another level using what we have previously termed an “ion escalator” or an “ion elevator” region.18 In the SLIM ion escalator, ions travel from one level to another via a transfer region (a small hole) located at the end of the ion path. Applying a DC bias to electrodes located above the hole on one level causes ions to move through the hole and enter an adjacent level. Such electrode arrangements on both sides of a PCB can be fabricated using multilayer designs, allowing SLIM electrodes to be placed on both surfaces of a PCB, as well as in and around the region surrounding the hole between levels. It is thus possible to create an ultralong path length system by stacking such SLIM surfaces.

Herein, we initially report on the performance of a multilevel SLIM module capable of achieving ultrahigh resolution over a wide mobility range. This initial SLIM module incorporates four ion levels, with each possessing a 10.8-m serpentine ion path, yielding a total path length of ~43-m. Ion switches15 are incorporated on each level and are used for transferring ions to either the mass spectrometer for analysis or to the next level for added separation. Theoretical and experimental transmission efficiencies and mass ranges of the new traveling-wave ion escalator are reported using Agilent tuning mixture phosphazene ions and reverse peptides to evaluate resolving power. Performance is further demonstrated using a phosphopeptide mixture.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Samples and Electrospray Ionization.

Low concentration Agilent tuning mixture was purchased from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA, USA), reverse-sequence peptides from Millipore-Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), and phosphopeptides from New England Peptide, Inc. (Gardner, MA, USA). The Agilent tuning mixture was used as received. The reverse peptides were run as a mixture and each was present at a 2 μM concentration in 50:50 water:acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid. Each component of a 42-component heavy labeled phosphopeptide mixture was present at a concentration of 300 nM in 70:30 water:acetonitrile with 0.5% formic acid. Ions were electrosprayed from a HF-etched silica emitter19 (20 μm i.d.) connected to a fused-silica capillary line (360 μm o.d., 100 μm i.d., Polymicro Technologies, Phoenix, AZ, USA). An electrically conductive microunion (Valco Instrument Co, Houston, TX, USA) was used to connect the emitter and capillary. Solution flow rates were controlled by a Harvard Apparatus syringe pump (Holliston, MA, USA) and were either 0.75 or 1.00 μL/min.

Instrumentation.

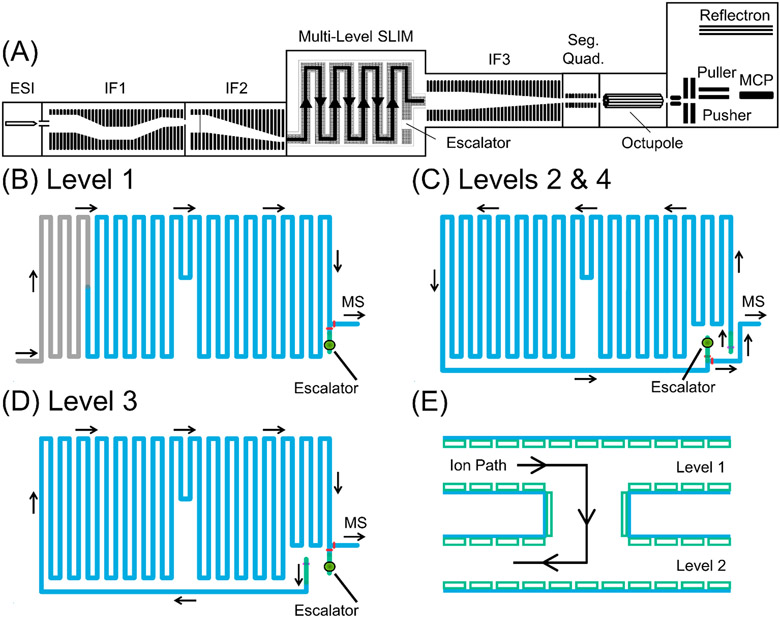

A schematic representation of the multilevel SLIM system is shown in Figure 1A. Ions generated by ESI were sampled using a multi-inlet capillary (5 × 250 μm i.d.).20 Ions were focused using two curved ion funnels: the first held at 10 Torr air (IF1), and the second between 2.9 and 4.0 Torr helium (IF2). A conductance limiting orifice (2.5 mm i.d.) separates IF1 and IF2. An electrically biased steel mesh (95% transmission) was placed after the eighth electrode in IF2 and was used as an ion gate. After IF2, ions traversed a conductance limiting orifice (2.5 mm i.d.) and entered the multilevel SLIM chamber held between 2.8 and 3.9 Torr helium. IF2 was always 100 mTorr above the pressure in the SLIM chamber. Ions exiting the SLIM were captured by a rectangular ion funnel (IF3) capable of accepting ions from any of the ion levels. The SLIM module and IF3 were held at the same pressure. Ions exited IF3 through a conductance limiting orifice (2.5 mm i.d.) and entered a third vacuum stage containing a segmented quadrupole held at ~0.14 Torr. Ions traversed the segmented quadrupole, passed through a skimmer, and were analyzed by an Agilent 6230 time-of-flight (TOF) MS. Signal from the TOF MCP was acquired using a U1084A 8-bit digitizer (Acqiris, Plan-les-Ouates, Switzerland) and processed using in-house software. The geometries of and voltages applied to the ion funnels are given in Table S1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of (A) the multilevel SLIM module, ion levels (B) one, (C) two and four, (D) three, and (E) a side view of the ion escalator. The coloring scheme in B–E is as follows: (gray trace) in-SLIM ion accumulation, (blue trace) ion separation, (red bar) ion switches, (green trace) ion escalator, (yellow circle w/black center) ion escalator orifice, (pink bar) ion escalator landing.

Multilevel SLIM Module.

The multilevel SLIM module consists of four distinct ion separation levels utilizing five stacked SLIM surfaces. The PCBs have copper electrodes and were fabricated from 2.35 mm thick FR-4 material. The top PCB possessed electrodes on only the bottom surface, while the other boards possessed electrodes on the top and bottom surfaces. Each level has a 10.8-m serpentine path incorporating a 6,5 electrode arrangement21 with RF extended electrodes, segmented TW electrodes, and DC guard electrodes, and with TWs established by applying potentials in repeated sequences of sets of 8 TW electrodes, as described previously.17 Dimensions for all electrodes are given in Table S2. Levels were spaced 3.15 mm apart. The top-down views of the four levels are shown in Figure 1B-1E. The first ion level has two separate TW regions: a 2.4 m in-SLIM ion accumulation region (Figure 1B, gray trace) and an 8.4 m separation region (Figure 1B, blue trace). The process of in-SLIM accumulation has been previously described.22 Ion switches (red bars), also described previously15 and in the Supporting Information (Figure S1), are located at the ends of the separation regions and control whether ions transfer to the mass spectrometer for detection or to the next SLIM level for additional separation. After traversing the ion escalator transfer region, ions enter the second level (Figure 1C), which contains one TW region used for extra separation. Ion levels 3 and 4 also only have one TW region. The ion escalators on sequential levels are not in the same physical position but are offset with the regions on every other level in the same position (ion escalators connecting levels 1 and 2 and levels 3 and 4 share the same ion escalator position (Figure 1B and 1D), and the ion escalator connecting levels 2 and 3 is similarly offset; (Figure 1C and 1E)). Photographs of the physical multilevel SLIM and an ion escalator (Figure S2) are given in the Supporting Information.

Traveling Wave-Based Ion Escalator.

DC and RF voltages were supplied to the three ion funnels, segmented quadrupole, and SLIM module using custom power supplies (Modular Intelligent Power Supply (MIPS), GAA Custom Engineering, LLC, Kennewick, WA, USA). Ion injections were performed by varying the voltages applied to the metal mesh in the second ion funnel and the conductance limiting orifice located between IF1 and IF2. The RF supplied to the SLIM module was split into 5 channels, each powering both sides of a PCB.

The ion escalator regions use TWs to transfer ions between levels, as opposed to DC biases used in previous designs.18 The transfer between two levels involves electrodes on surfaces spanning three PCBs, and a 3.0 mm long × 6.2 mm wide hole cut through the middle PCB (Figure 1B-1E, green trace). Two opposing sides of the hole are lined with TW and RF electrodes to aid in transferring ions between ion levels, and the other two sides with DC guard electrodes. More detailed views of the interior of the hole, including a top-down view (Figure S3A) and an interior view (Figure S3B), are given in the Supporting Information. The TW electrodes inside the ion escalator are 2.35 mm long (the PCB thickness), as opposed to the 1.03 mm length on the surfaces. Ions are carried to the ion escalator region by two TW (8-electrode) sequences located after the ion switch, and before the ion escalator. The TWs applied to these 16 electrodes move in the same direction as the main track. There are 8-TW electrodes opposite the hole possessing TWs moving in the reverse direction. There are also 3-TW electrode arrays above and below the ion escalator where the forward and reverse TWs meet. To transfer ions between SLIM levels, ions are carried by the forward-moving TWs and encounter the reverse TWs in the middle of the hole where their combined effect pushes ions into the hole (Figure 1F). The TW electrodes lining the inside of the gap further assist the transfer, and then TWs moving in the reverse direction (compared to the previous SLIM level) move ions toward the main ion track of the new level. A video of a simulation for ten m/z 602 ions traversing the ion escalator is given in the Supporting Information. A pictorial representation of the TW sequence (HHHHLLLL) is also given in Figure S4. As discussed later, applying lower TW speeds to the ion escalator, akin to ion “surfing” mode,7 aids in ion transmission. To ensure that the lower speed TW in the ion escalator was synchronized with the higher speed TW in the separation region, it is necessary to apply whole number fractions of the main TW speed to the ion escalator. For example, if the main TW speed was 192 m/s, speeds of 192, 96, 64, 32, 24, 12, or 6 m/s could be applied to the ion escalator and be effectively synchronized with the separation region TW.

Data Analysis.

Mobility peak areas were calculated by summing the intensities of ions over their respective drift times. Data processing and figure plotting were performed in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick MA USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Ion Trajectory Studies.

SIMION 8.1 simulations were initially performed to evaluate the transfer of ions between SLIM levels using TWs. Simulation details are provided in the Supporting Information. We explored ion transfer under “surfing” conditions where ions move at the same speed as the TWs, as opposed to “separation” conditions. Since the total length of the ion escalator is only about 3.5 cm, compared to the 10.5 m separation region of a single ion level, the small time ions spend surfing does not significantly detract from the overall separation quality. To achieve surfing conditions, low TW speeds and/or high amplitudes are required.

The first simulations evaluated the effects of TW speed on ion transmission through the ion escalator. Each simulation used 1000 ions with m/z 1034 (K0 = 2.09 cm2/(V*s)). The buffer gas was helium. Ion trajectories using TW speeds of 16, 32, and 64 m/s are shown in Figures 2A and S5A and S5C, respectively. Blue arrows show the direction of ion motion. As can be seen, ions traversed the ion escalator at all three TW speeds. The most notable difference among the three ion trajectories is that the 64 m/s simulation showed some ions moving into the region opposite the ion escalator where the reverse TW is applied. This likely occurred because ions experienced rollover events that prevented them from traversing the ion escalator with the first (or subsequent) TW period.

Figure 2.

(A) Ion trajectory simulations of 1000 ions of m/z 1034 traversing the ion escalator using 16/s TW speed and 40 Vpp TW amplitude. (B) Simulated mobiligrams of negative Agilent tune mix ions (m/z 602 (red), 1034 (green), 1334 (blue), 1634 (orange), 1934 (pink), 2234 (purple), 2534 (light gray), and 2834 (dark gray)) using 16 m/s TW speed. Each simulation in panel B utilized 1000 ions per m/z. Data sets were normalized to the m/z with the highest intensity. Guard = −5 V, RF = 300 Vpp, P = 3.5 Torr helium.

Simulations of ions spanning a wide mobility range were also performed using negative Agilent tuning mixture ions with m/z values of 602, 1034, 1334, 1634, 1934, 2234, 2534, and 2834. The reduced mobilities of these ions in helium are 2.96, 2.09, 1.88, 1.67, 1.51, 1.40, 1.29, and 1.23 cm2/(V*s), respectively, and were calculated using literature CCS values.23 Drift time plots of the nine m/z’s acquired using 16 m/s TW speed are shown in Figure 2B. When 16 m/s was used, most high and low mobility ions exhibited arrival time distributions centered around 1.8 ms, which is indicative of “surfing”. As the straight-line path length from ion creation to termination is 33.4 mm, and since the TW speed was 16 m/s, dividing the straight-line path length by the TW speed produces an arrival time of approximately 2 ms, in good agreement with the expectation for surfing.

At 32 m/s TW speed (Figure S5B), most ions exhibited arrival times corresponding to one TW period (0.9 ms at 32 m/s), showcasing efficient transfer through the ion escalator. However, one or two additional peaks emerged for the lowest mobility ions, corresponding to ion transfer after one or two TW rollover events, respectively. Additional rollover events became apparent when the TW speed was increased to 64 m/s (Figure S5D) where all but the highest mobility ions (m/z 602) exhibited additional peaks after the surfing peak. Although it is possible for ions to transfer to the next SLIM level under separation conditions, the presence of rollover events will likely cause ions to not traverse the ion escalator, which would lead to peak broadening and ion losses. As demonstrated in Figure 2B, ions of all mobilities traverse the ion escalator most efficiently when moving under surfing conditions, which is achieved by using low speed, high amplitude TWs.

Initial Multilevel SLIM Module Characterization.

Agilent Tuning Mix.

The current multilevel SLIM module has four levels constructed from five PCBs and three ion escalators transfer regions between levels. Ions from any of the four ion levels can be routed to the mass spectrometer using ion switches, allowing for the characterization of the performance of 1–4 levels.

Figure 3A shows mobiligrams for Agilent tuning mixture negative ions obtained with the SLIM using one to four ion levels. A 40 ms ion injection time was performed using in-SLIM ion accumulation with 27 Vpp and 192 m/s TW separation conditions. The TW applied to the ion escalator was set to 24 m/s (in accordance with simulations) and was synchronized to the separation TW (192/24 = 1/8 main TW speed). The guard voltage was −35 V in both regions. Using one SLIM level, eight baseline resolved peaks were detected (Figure 3A, red): m/z (1) 602, (2) 1034, (3) 1334, (4) 1634, (5) 1934, (6) 2234, (7) 2534, and (8) 2834, showing good separation was achieved over this wide mass and mobility range on the first level. The asterisk (*) next to the peak number 1 indicates that the first peak was comprised of m/z values 432 and 602, which were surfing under these specific TW and pressure conditions. After optimization using one ion level, ions were sent through the first TW ion escalator to the second SLIM level (Figure 3A, green). As expected, improved separation was observed. The maximum peak height of each peak was somewhat lower and peak width was greater, as expected for a longer path length separation. Ions were then sent through three and four ion levels, where an even greater separation was obtained (Figure 3A, blue and orange). Some of the large m/z ions developed small tails due to small inefficiencies traversing the ion escalator, but the smaller ions did not. The combination of TW conditions, and guard voltage used here provided the best compromise between peak shape and ion intensity over a wide mobility range. Importantly, these data show that the ion escalator is capable of transmitting a wide range of mobilities.

Figure 3.

(A) Separation of Agilent tune mix negative ions using one, two, three, and four ion levels. (B) Ion transmission efficiencies across successive levels normalized to the intensity obtained using one level. TWsep speed = 192 m/s, TWsep amplitude = 27 Vpp, TWesc speed = 24 m/s, TWesc amplitude = 22 Vpp, guard = −35 V, P = 2.8 Torr helium.

The transmission efficiency of the TW ion escalator was examined using the peak areas of Agilent tuning mixture ions obtained using one, two, three, and four ion levels (Figure 3B). As can be seen, 100% transmission efficiency (error bars represent 1 standard deviation) was obtained for m/z values 602, 1034, 1334, and 1634. For ions with m/z > 1634, some losses were observed; ~10% of ions with m/z’s 1934 and 2234 were lost after traversing all four ion levels (~3.3% loss per ion escalator). About 70% transmission for m/z 2534 was observed, corresponding to 10% loss per ion escalator, and ~20% for m/z 2834. We speculate these losses likely occurred because surfing conditions were not met for these lower mobility ions. As stated earlier, surfing conditions can be created by using lower TW speeds or higher TW amplitudes. To explore how TW amplitude affected ion transmission through the ion escalator, the amplitude applied to the ion escalator was varied while keeping the voltages applied to the separation region constant. Ion signal was recorded after ions passed through all 4 ion levels. We observed (Figure S6) a constant signal for TWesc amplitude 12–27 Vpp for m/z’s 602 to 1934. The ion signals were lower when TW voltages were either very low (7 Vpp) or very high (37 Vpp). Losses associated with low amplitudes are consistent with nonsurfing conditions. Alternatively, losses associated with high amplitudes were most noticeable for lower mobility ions (e.g., m/z’s 2534 and 2834). We speculate that the higher amplitude, lower speed TWs in ion escalator region inhibited low mobility ions from making the transition from the higher speed, lower amplitude TWs in the separation region. In such a case lower mobility ions might experience multiple rollover events and be effectively trapped in this region and eventually lost. Further experiments are needed to explore this hypothesis, but currently, the optimum arrangement is to use lower amplitude TWs in the ion escalator region compared to the separation region.

Previous SLIM studies have shown that the guard voltage has a relatively small effect on ion transmission and resolution in the main separation path.24 However, we observed that the guard voltage does have a significant effect on transmission and peak shapes of lower mobility ions as they traverse the ion escalator. This effect was explored by first sending ions through the first ion level (Figure S7A). The voltage at which peak shapes were the most Gaussian was −25 V (purple), which was deemed “optimum”. When the guard voltage was closer to 0 V, peaks exhibited tailing that became more pronounced as guard voltage became more positive (e.g., −25 to −5 V). Increasing the guard voltage (e.g., −25 to −45 V) caused increasing peak “fronting”. In contrast, when ions were transmitted through all four ion levels (Figure S7B), peak tailing was observed for guard voltages up to −35 V, with Gaussian peak shapes mostly recovered at −45 V (but where low mobility ions were lost). It is likely that the 3.15 mm surface spacing used in this multilevel SLIM necessitates larger guard voltages to achieve sufficient field penetration compared to previous single-level SLIM utilizing 2.75 mm board spacing. Currently, there is no ability to independently control the guard voltages in the separation and ion escalators, but future work will address this issue.

Reverse Peptides.

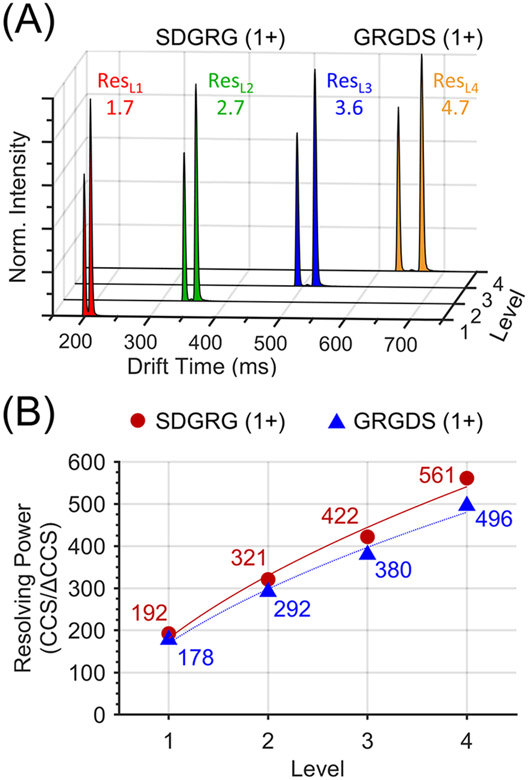

To further evaluate the separation capabilities of the multilevel SLIM, we used two commonly studied reverse-sequence peptides, SDGRG1+ and GRGDS1+, with 10 ms in-SLIM ion accumulation. Mobiligrams for separations using 1–4 SLIM levels (Figure 4A) show nearly baseline separation between the two reverse peptides using one level (red trace), with baseline separation using 2 levels (green trace). Further separation was achieved using 3 and 4 levels (blue and orange traces). The relative intensity difference is largely attributed to peptide purity: 90% for SDGRG and 97% for GRGDS.

Figure 4.

(A) Separation of the reverse peptides SDGRG1+ and GRGDS1+ using the multilevel SLIM. (B) Peak–peak resolution as a function of SLIM level. TWsep speed = 256 m/s, TWsep amplitude = 27 Vpp, TWesc speed = 32 m/s, TWesc amplitude = 22 Vpp, P = 3.9 Torr helium.

A resolution for the peptides for different numbers of SLIM levels was calculated using eq 2

| (2) |

where td is drift time and fwhm is full width at half-maximum.25,26 Each reverse peptide was fit to a Gaussian to obtain values for drift time and fwhm. The peak–peak resolutions for the two reverse peptides using one to four SLIM levels were 1.7, 2.7, 3.6, and 4.7, respectively (1.5 is considered baseline separation). Additionally, the resolving power in the CCS domain was calculated using eq. 3 using known CCS values (130 and 132 Å2 for SDGRG1+ and GRGDS1+, respectively27), and the results are shown in Figure 4B. The highest resolving power achieved was 561 and was obtained for SDGRG1+ after separation using 4 levels.

| (3) |

The resolving power for SDGRG1+ increased from 192 using one ion level to 561 using four SLIM levels, representing a 2.9× increase (GRGDS1+ was similar). This result is more than the expected increase in resolving power due to the factor of 4 increase in path length. The ratio of resolving powers between successive levels were calculated to be 1.7, 1.3, and 1.3 (level 1 to level 2, level 2 to level 3, and level 3 to level 4, respectively), implying a discrepancy at the first ion level. This can be explained by the fact that in-SLIM accumulation was used as the ion introduction method, meaning ions did not actually traverse a full 10.8-m on the first ion level but rather only a fraction of this length (see Figure 1B, gray trace). In a separate work we will report on details of the in-SLIM ion accumulation process. The key point relative to the present work is that only a portion of the first region is used for accumulation, allowing more of the first level to be used for separation. The set of parameters used here provided the optimum resolution and resolving power and show no significant contribution to ion diffusion in the ion escalator region because of the use of surfing conditions.

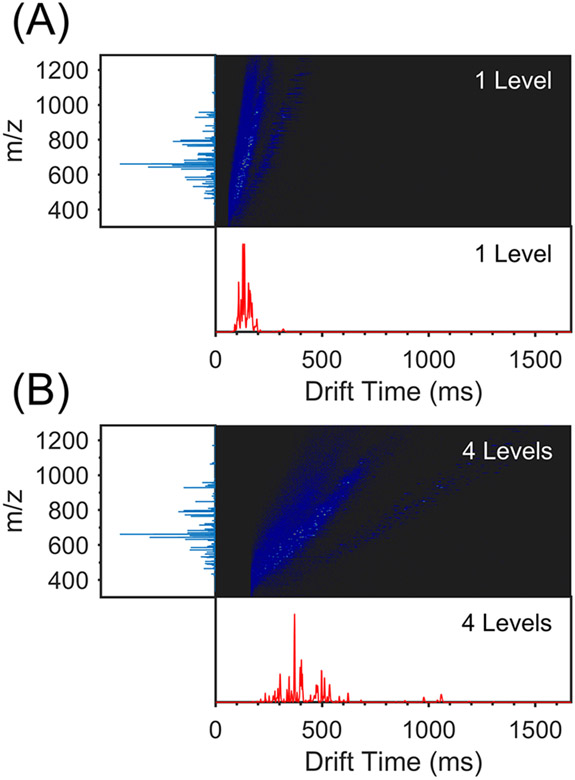

Phosphopeptide Mixture.

A complex mixture of 42 heavy labeled phosphopeptides was also examined (Supporting Information, Table S3) and the results obtained using one ion level are shown in Figure 5A. The most and least mobile phosphopeptide ions detected were m/z’s 441 and 1321, which correspond to the 3+ and 1+ charge states of the peptide GSDAS(p)GQLFHGR. The addition of a phosphate group to an amino acid is specified by (p). The mobiligram obtained after using one SLIM level shows many phosphopeptides incompletely resolved or unresolved. Using 4 SLIM levels (Figure 5B), much greater ion separation was obtained. The phosphopeptide mixture also contained three peptides having phosphoserine (S(p)) phosphosite isomers: (1) TPS(p)SE-EISPTK and TPSSEEIS(p)PTK, (2) SS(p)SPELVTHLK and SSS(p)PELVTHLK, and (3) TPS(p)SEEISPTKFPGLYR and TPSSEEIS(p)PTKFPGLYR. Detailed views of the separation of the 2+ charge state of TPSSEEISPTK (m/z 632) are shown in Figure S8A and S8B. Ions exhibited a significant amount of overlap when one ion level was used, with a small hump on the peak tail being the only indication of the presence of isomers. However, the isomers resolved into two baseline-separated peaks upon sending ions through all four SLIM levels. A similar separation was observed for the 2+ charge state of SSSPELVTHLK (m/z 643), wherein the ions were largely unseparated in one SLIM level (Figure S8C), but near baseline-separated in four SLIM levels (Figure S8D). Two partially resolved peaks corresponding to the 2+ charge state of TPSSEEISPTKFPGLYR (m/z 1000) were also observed with low signal intensities using one ion level (Figure S8E). Using four SLIM levels, baseline separation was readily achieved (Figure S8F), showcasing the ability of the multilevel SLIM to separate complex mixtures with high resolution over a wide mobility range.

Figure 5.

Mobiligrams and intensity maps of a 42-component phosphopeptide mixture obtained using (A) one and (B) four ion levels. TWsep speed = 256 m/s, TWsep amplitude = 32 Vpp, TWesc speed = 32 m/s, TWesc amplitude = 32 Vpp, guard = 40 V, P = 3.6 Torr He.

CONCLUSION

We report and initially demonstrate the development of a new multilevel SLIM module capable of achieving ultra high resolution over a wide mobility range. The performance of a new TW-based ion escalator was first evaluated in SIMION and then implemented experimentally. A resolving power of up to ~560 was obtained for a mixture of reverse peptides. Efficient transmission of high mobility ions between levels was obtained through the ion escalator, but some losses were observed in this initial work for ions with very low mobilities (high m/z). Preliminary simulations suggest that decreasing board thickness and the spacing between SLIM surfaces will decrease the distance ions must travel through the ion escalator and reduce or eliminate any such losses. The ability to independently control the guard voltages applied to the separation and ion escalator region regions is expected to also maintain peak shapes.

The ability to separate ions having a wide mobility range in conjunction with ultrahigh resolution will be broadly applicable to, for example, complex biological mixture analysis. We note that the general approach provides the basis for further stacking of SLIM levels to achieve even greater resolution/resolving power without the use of multiple passes and the inherent limitations upon mobility range. In addition, the use of multiple passes with greater mobility ranges should be able to be readily implemented in future designs by the addition of another ion path to route ions back to level one. Finally, we note that multilevel SLIM provide a basis for the fabrication of much more compact devices that can exploit the high resolving powers and broad flexibility provided by SLIM, potentially allowing for portable field analysis for a host of applications.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Bryson Gibbons for work on the ion mobility viewing tool. This work utilized capabilities developed under the support of NIH National Cancer Institute (R33 CA217699) and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01 GM130709-01 and P41 GM103493-15). This project was performed in the Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory, a DOE OBER national scientific user facility on the PNNL campus. PNNL is a multiprogram national laboratory operated by Battelle for the DOE under contract DE-AC05-76RL01830.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c01397.

SLIM electrode dimensions; ion funnel dimensions; ion switch schematic; photographs of multilevel SLIM and ion escalator hole; schematics of ion escalator from different views; ion trajectory simulations and associated mobiligrams using other TW speeds; description of SIMION parameters; effect of ion escalator TW amplitude on ion transmission efficiency; effect of guard voltage on ion transmission efficiency; list of heavy-labeled phosphopeptides; and separations of phosphopeptide isomers (PDF)

Simulation for ten m/z 602 ions traversing the ion escalator (MP4)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Adam L. Hollerbach, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States

Ailin Li, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States.

Aneesh Prabhakaran, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States.

Gabe Nagy, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States.

Christopher P. Harrilal, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States

Christopher R. Conant, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States

Randolph V. Norheim, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States

Colby E. Schimelfenig, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States

Gordon A. Anderson, GAA Custom Engineering, LLC, Benton City, Washington 99320, United States

Sandilya V. B. Garimella, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States

Richard D. Smith, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States.

Yehia M. Ibrahim, Biological Sciences Division, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, Washington 99354, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Cohen MJ; Karasek FW J. Chromatogr. Sci 1970, 8, 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kanu AB; Dwivedi P; Tam M; Matz L; Hill HH Jr. J. Mass Spectrom 2008, 43, 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kirk AT; Bohnhorst A; Raddatz C-R; Allers M; Zimmermann S Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2019, 411, 6229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Siems WF; Wu C; Tarver EE; Hill HH Jr.; Larsen PR; McMinn DG Anal. Chem 1994, 66, 4195–4201. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Cumeras R; Figueras E; Davis CE; Baumbach JI; Gracia I Analyst 2015, 140, 1376–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ridgeway ME; Lubeck M; Jordens J; Mann M; Park MA Int. J. Mass Spectrom 2018, 425, 22–35. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Shvartsburg AA; Smith RD Anal. Chem 2008, 80, 9689–9699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kolakowski BM; Mester Z Analyst 2007, 132, 842–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Merenbloom SI; Glaskin RS; Henson ZB; Clemmer DE Anal. Chem 2009, 81, 1482–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Deng L; Ibrahim YM; Hamid AM; Garimella SVB; Webb IK; Zheng X; Prost SA; Sandoval JA; Norheim RV; Anderson GA; Tolmachev AV; Baker ES; Smith RD Anal. Chem 2016, 88, 8957–8964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Deng L; Webb IK; Garimella SVB; Hamid AM; Zheng X; Norheim RV; Prost SA; Anderson GA; Sandoval JA; Baker ES; Ibrahim YM; Smith RD Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 4628–4634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Giles K; Ujma J; Wildgoose J; Pringle S; Richardson K; Langridge D; Green M Anal. Chem 2019, 91, 8564–8573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Fernandez-Lima FA; Kaplan DA; Park MA Rev. Sci. Instrum 2011, 82, 126106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Shvartsburg AA; Clemmer DE; Smith RD Anal. Chem 2010, 82, 8047–8051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Garimella SVB; Ibrahim YM; Webb IK; Ipsen AB; Chen T-C; Tolmachev AV; Baker ES; Anderson GA; Smith RD Analyst 2015, 140, 6845–6852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wojcik R; Nagy G; Attah IK; Webb IK; Garimella SVB; Weitz KK; Hollerbach A; Monroe ME; Ligare MR; Nielson FF; Norheim RV; Renslow RS; Metz TO; Ibrahim YM; Smith RD Anal. Chem 2019, 91, 11952–11962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ibrahim YM; Hamid AM; Deng L; Garimella SVB; Webb IK; Baker ES; Smith RD Analyst 2017, 142, 1010–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ibrahim YM; Hamid AM; Cox JT; Garimella SV; Smith RD Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 1972–1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Kelly RT; Page JS; Luo Q; Moore RJ; Orton DJ; Tang K; Smith RD Anal. Chem 2006, 78, 7796–7801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Smith RD; Kim T; Udseth HR Ionization source utilizing a multi-capillary inlet and method of operation. US 6803565, October 12, 2004.

- (21).Hamid AM; Ibrahim YM; Garimella SVB; Webb IK; Deng L; Chen T-C; Anderson GA; Prost SA; Norheim RV; Tolmachev AV; Smith RD Anal. Chem 2015, 87, 11301–11308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Deng L; Garimella SVB; Hamid AM; Webb IK; Attah IK; Norheim RV; Prost SA; Zheng X; Sandoval JA; Baker ES; Ibrahim YM; Smith RD Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 6432–6439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Stow SM; Causon TJ; Zheng X; Kurulugama RT; Mairinger T; May JC; Rennie EE; Baker ES; Smith RD; McLean JA; Hann S; Fjeldsted JC Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 9048–9055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Li A; Garimella SVB; Ibrahim YM Analyst 2020, 145, 240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Dodds JN; May JC; McLean JA Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 12176–12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Jeanne Dit Fouque K; Ramirez CE; Lewis RL; Koelmel JP; Garrett TJ; Yost RA; Fernandez-Lima F Anal. Chem 2019, 91, 5021–5027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bush MF; Hall Z; Giles K; Hoyes J; Robinson CV; Ruotolo BT Anal. Chem 2010, 82, 9557–9565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.