Abstract

Background:

Risky sexual behaviors (RSBs) are behaviors that could result in unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections. These behaviors are often initiated during adolescence, and the frequency of engagement in such behaviors rises with increasing age during the teenage years. It has been asserted that exposures to sexual materials early in life could lead to early sex debut among adolescents.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to determine the early life exposures contributing to RSBs among basic school pupils in the Twifo Praso District of Ghana.

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted using a structured questionnaire. Three hundred and sixty basic school pupils were selected by simple random sampling technique. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20.

Results:

The study found that 64.4% of the respondents have had sexual intercourse at a mean age of 13.7 years. Respondents from polygamous homes were more likely to engage in earlier sexual debut than those from monogamous home (r = 0.0343, P = 0.003). Furthermore, having a high number of friends who have had sex was associated with an early sexual debut (r = 0.720, P = 0.000).

Conclusion:

Adolescents are initiating sexual intercourse very early in life and this calls for customized reproductive health promotion activities aimed at minimizing risky sexual behaviors. Further studies on how parent–child sexual communication could delay sexual debut are recommended.

Keywords: Adolescents, pupils, risky behaviors, sexual behavior

INTRODUCTION

Adolescents are persons with specific health and developmental needs.1 The age at which these adolescents begin sexual debut is of significant public health importance because people who begin having sexual intercourse at younger ages are more likely to engage in sexual intercourse with casual partners and multiple and concurrent partnerships and hence risky sexual behaviors (RSBs).2 RSBs refer to sexual activities that could lead to unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV/AIDS.3 This also includes having multiple sexual partners or having sex without using any contraceptive. The initiation of the first sex before 18 years, involvement in commercial sex, and sex activity under the influence of alcohol are all regarded as RSB.4,5,6 Adolescents' sexual debut also marks the exposure to sexual and reproductive health diseases.7 Therefore, early sexual debut increases the risk of STIs and teenage pregnancies.7 Other outcomes noticed among adolescents who engage in early sexual debut are involved in several types of social vices such as stealing, fighting, use of controlled substances, school absenteeism, and increased number of friends.8 The mean age at which adolescents engage in their first sexual intercourse varies among different cultural and geographical settings and majorly depends on economic factors, peer influence, and acceptable cultural practices.9

In sub-Saharan Africa, over 50% of adolescent women and 45% of their male counterparts have had sex before their 18th birthday.10 This creates a wide gap between the initiation of sexual activities and marriage as well as a premarital sexual act. This early sexual debut coupled with the long periods of premarital sex increases the risk of unwanted pregnancies and HIV infections.10

In Ghana and the African subregion, females initiate sexual debut earlier; 8.2% of young women and 3.6% of young men had their first sexual intercourse before the ages of 15 years.11 The age at sexual debut is increasing among younger females; 27% by the ages of between 15 and 19 years have initiated sexual coitus. Males however are showing a decreasing age at sexual debut.12 Studies in other contexts have equally investigated the age at sexual debut and how early sexual debut affects sexual behaviors of the adolescent.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 It has, however, become imperative to find out the relationship between individual and system factors or exposures and RSBs of the adolescent. This will facilitate the planning and delivery of reproductive health promotion activities that meet the needs of the adolescent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area

The study was conducted among basic school pupils at Twifo Praso. Twifo Praso is the capital town of Twifo Atti-Mokwa District, a district in the Central Region of Ghana. The town has a population of about 68,216 people.21 The dominant occupation of the people at Twifo Praso is farming and few people are engaged with fishing activities. There are also quite several people who work in the civil service, trading, and other commercial activities.

Population and sample size

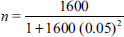

Data from the district education office and also confirmed from the staff of Twifo Praso basic school indicate that the school has a population of 1600 pupils as of the 2018/2019 academic year. The sample size was determined using the formula below.22

where n is the sample size, N (1600) is the population size, and e (0.05) is the level of precision.

n = 320

An additional 12% was added to make up for incomplete responses and to increase the statistical power. Therefore, a sample size of 360 pupils was used. During schooling hours every weekday, a simple random sampling technique was then used until the required number of pupils was obtained for the study.

Data collection and analysis

This was a descriptive cross-sectional study which involved the systematic collection of data with a structured questionnaire. Data collection was done using closed-ended questions designed by the researchers. The questionnaire development was a collaborative and iterative process where the researchers met to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development, guided by similar studies elsewhere and the objectives of our study. The questionnaire was based on pupils' demographic characteristics relevant to our study (age, age at sexual debut, type of home, and parenting style), type of friends, and exposures to mass media sexual materials. The questionnaire was piloted using 15 pupils from Agogo Methodist basic school which has similar population characteristics with our study area. After the piloting, no significant adjustment was necessary to the questionnaire. Responses from the pilot study were not included in our final data analysis. Questionnaire was self-administered since all participants could read and write. Throughout the 3-week period of data collection, the authors (JNS and POA) were involved in distributing questionnaires and collecting completed ones. All 360 participants completed and returned their questionnaire. The returned questionnaire was screen for completeness of information.

All the 360 questionnaires were rightly answered and analyzable. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20 IBM SPSS Statistics for windows, IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA. The results are summarized in Tables 1-7. Thus, data were analyzed to answer the following research questions: What is the age at which adolescents initiate their first sex? What are the various sexual materials or information that adolescents are exposed to? Is there any relationship between sexual behaviors of adolescents and their exposure to various sexual materials?

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents

| Demographics | Frequency (n=360), n (%) | Mean age | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 180 (50.0) | ||

| Female | 180 (50.0) | ||

| Age | |||

| 13 | 50 (13.9) | ||

| 14 | 54 (15.0) | ||

| 15 | 90 (25.0) | 15.6 | 1.8 |

| 16 | 66 (18.3) | ||

| 17 | 50 (13.9) | ||

| 18 | 50 (13.9) | ||

| Total | 360 (100.0) | ||

| Current form | |||

| JHS 1 | 76 (21.1) | ||

| JHS 2 | 128 (35.6) | ||

| JHS 3 | 156 (43.3) |

Source: Field survey (2019). SD – Standard deviation

Table 7.

Relationship between exposure to mass media and early sexual debut

| Exposure to sexual materials in mass media | Ever had sex |

Total | Crude OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |||

| Nude pictures of the opposite sex | ||||

| Yes | 179 (86.5) | 28 (13.5) | 208 (100.0) | 2.53 (1.61-3.98) |

| No | 52 (34.2) | 100 (65.8) | 152 (100.0) | 0.21 (0.10-0.42) |

| Pornographic (“blue” films) | ||||

| Yes | 160 (88.9) | 20 (11.1) | 180 (100.0) | 2.22 (1.53-3.23) |

| No | 72 (40.0) | 108 (60.0) | 180 (100.0) | 0.19 (0.08-0.44) |

| Music videos portraying nude pictures | ||||

| Yes | 168 (85.7) | 27 (14.3) | 196 (100.0) | 2.20 (1.48-3.27) |

| No | 64 (39.0) | 100 (61.0) | 164 (100.0) | 0.23 (0.11-0.49) |

| Social media containing nude pictures | ||||

| Yes | 168 (95.5) | 8 (4.5) | 176 (100.0) | 2.74 (1.84-4.10) |

| No | 64 (34.8) | 110 (65.2) | 184 (100.0) | 0.07 (0.02-0.27) |

Source: Field survey (2019). OR – Odds ratio; CI – Confidence interval

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Presbyterian University College, Ghana. Only pupils who consented voluntarily were sampled to participate in the study.

RESULTS

A total of 360 questionnaires were administered and all were completed and analyzed. Thus, the response rate was 100%. The study showed that many (43.3%) of the respondents were between the ages of 15 and 16 years. The rest were between 13 and 14 years (28.9%) and 17 and 19 years (27.8%). The mean age of the respondents was 15.6 years, with a standard deviation of ±1.8 [Table 1]. With reference to the current level of the study of the respondents, the study found that 43.3% were in junior high school 3, 35.6% in junior high school 2, and the rest (21.1%) were in junior high school 1. Details of the demographic information of participants are provided in Table 1.

It was identified that the majority (64.4%) of the respondents have had sexual intercourse. The mean age at sexual debut was 13.7 years. Many of them (31.0%) had their coitarche at 14 years. The ages at early sexual debut were at 15 years (22.4%), at 13 years (15.5%), at 11 years (12.1%), at 12 years (8.6%), at 16 years (6.9%), and at 17 years (3.4%). As indicated [Table 2], more female respondents (42.3%) initiated sexual intercourse before the mean age (13.7 years) than male respondents (31.3%) and the difference was statistically significant (r = 0.019, P = 0.036).

Table 2.

Association between selected variables and sex of the respondents

| Demographics | Sex of the respondents, n (%) |

Pearson’s R | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Coitarche (years) | ||||

| 11 | 16 (57.1) | 12 (42.9) | 0.019 | 0.036 |

| 12 | 8 (40.0) | 12 (60.0) | ||

| 13 | 16 (44.4) | 20 (55.6) | ||

| 14 | 56 (77.8) | 16 (22.2) | ||

| 15 | 16 (30.8) | 36 (69.2) | ||

| 16 | 16 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| 17 | 0 | 8 (100.0) | ||

| Number of sexual partners | ||||

| None | 16 (100.0) | 0 | 0.317 | 0.047 |

| One | 80 (60.6) | 52 (39.4) | ||

| Two | 32 (38.1) | 52 (61.9) | ||

Source: Field survey (2019)

Chi-square test and Pearson's correlation were used to assess the association and the strength of association between parenting style or type of home and sexual debut [Table 3]. The study found that respondents who were from single or broken homes had early sexual debut than those from nonmaladjusted homes. However, all respondents from single fatherhood homes had early sexual debut than those from single motherhood homes (90.8%). Nevertheless, there was a weak association between the type of home and early sexual debut and the difference was statistically significant (r = 0.324, P = 0.005). The study participants from polygamous homes had early sexual debut than those from monogamous home (r = 0.0343, P = 0.003).

Table 3.

Association between selected variables and sexual debut of the respondents

| Type of parenting/parenthood | Ever had sex, n (%) |

Pearson’s R | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Type of home | ||||

| Mother single parenting | 72 (90.0) | 8 (10.0) | 0.324 | 0.005 |

| Father single parenting | 16 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| Both | 144 (54.5) | 120 (45.5) | ||

| Number of father’s wives | ||||

| One | 161 (55.9) | 127 (44.1) | −0.343 | 0.003 |

| Two | 46 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| Three | 26 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| Number marriages mother have had | ||||

| One | 188 (59.5) | 128 (40.5) | −0.267 | 0.032 |

| Two | 40 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| Three | 4 (100.0) | 0 | ||

Source: Field survey (2019)

Table 4 depicts that the majority of the respondents (73.3%) affirmed that their sexual behavior was influenced by their peers. Some respondents indicated that they talked about sexual activities almost all the time with their peers. The study participants who had friends that have ever had sex were more likely to be engaged in early sexual intercourse than adolescents whose friends never had sex (r = 0.720, P = 0.000).

Table 4.

Association between peer influence and sexual behaviors

| Peer influence | Ever had sex, n (%) |

Pearson’s R | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Have you friends who have had sex | ||||

| None of them | 0 | 32 (100.0) | 0.720 | 0.000 |

| Just a few of them | 8 (16.7) | 40 (83.3) | ||

| About half of them | 42 (42.1) | 44 (57.9) | ||

| Almost all of them | 148 (92.5) | 12 (7.5) | ||

| All of them | 11 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| Frequency you engage in sexual talks | ||||

| Never | 0 | 12 (100.0) | 0.694 | 0.000 |

| Rarely | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | ||

| Sometimes | 43 (81.1) | 10 (18.9) | ||

| Almost every time | 44 (100.0) | 0 | ||

Source: Field survey (2019)

Table 5 shows that adolescents were exposed to several types of sexual materials from a variety of sources, including the mass media and the peer friends. The study participants who were exposed to a greater number of sexually exciting materials were more likely to engage in early sexual debut than those with less exposures (r > 0.650, P < 0.05). The most common materials respondents were exposed to included pornographic films and naked pictures of the opposite sex. Binomial logistic regression to show the relationship between exposure and early sexual debut is presented in Table 6. Further details in Table 7 suggest that respondents who frequently watched nude pictures of the opposite sex (86.5%) were 2.53 times more likely to engage in early sexual debut than respondents who were not exposed to nude pictures of the opposite sex (34.2%) (odds ratio [OR] = 2.53 [95% confidence interval (CI); (1.61–3.98])). The odds of watching music videos and early sexual debut was 2.20 (OR = 2.20 [95% CI; (1.48–3.27)]), while the odds of watching nude pictures on the social media and early sexual debut was 2.74 (OR = 2.74 [95% CI; (1.84–4.10)]).

Table 5.

Exposures to sexual media materials by the respondents

| Media exposures | Frequency (n=360), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sexual materials’ respondents were exposed to | |

| Nude pictures of the opposite sex | 208 (57.8) |

| Pornographic (“blue films”) | 180 (50.0) |

| Music videos portraying nude pictures | 196 (54.4) |

| Social media containing nude pictures | 176 (48.9) |

| None of the above | 61 (16.9) |

| Sources of sexual materials | |

| Renting from shops | 16 (4.4) |

| Internet download | 84 (23.3) |

| Borrowing from friends | 240 (66.7) |

| Television channels | 168 (46.7) |

Source: Field survey (2019)

Table 6.

Association between media exposures and early sexual debut

| Media exposures | Ever had sex, n (%) |

Pearson’s R | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Unhealthy sexual materials | ||||

| Never | 0 | 8 (100.0) | 0.818 | 0.000 |

| Rarely | 32 (40.0) | 48 (60.0) | ||

| Sometimes | 200 (96.2) | 8 (3.8) | ||

| Sexual music videos | ||||

| Never | 0 | 44 (100.0) | 0.768 | 0.000 |

| Rarely | 8 (11.1) | 64 (88.9) | ||

| Sometimes | 145 (88.6) | 20 (11.4) | ||

| Almost every time | 68 (100.0) | 0 | ||

| Listened sexual related | ||||

| Never | 0 | 56 (100.0) | 0.651 | 0.000 |

| Rarely | 22 (42.9) | 30 (57.1) | ||

| Sometimes | 188 (82.5) | 40 (17.5) | ||

| Almost every time | 20 (100.0) | 0 | ||

Source: Field survey (2019)

DISCUSSION

The age at which adolescents begin sexual intercourse is of significant public health importance, as it has been found to expose them to potential risky outcomes both in the short and long term.23 Studies in other contexts have equally identified that adolescents were engaging in sexual activities even before their 13th birthday.23,24 This suggests that adolescents start having sexual relationships as early as 11 years, and therefore, parents, guardians, and health workers should start reproductive health education as early as possible, aimed at empowering children even before they turn 11 years.

Of those who have ever had sex, the study found that 16.7% of them had sex with nonregular sexual partners. This finding is congruent with the study by Uchudi et al. who stated that people who begin having intercourse at younger ages are more likely to engage in sexual intercourse with casual partners and to have multiple and concurrent partnerships.25 This behavior, in no doubt, put these young ones at high risk for STIs including HIV/AIDS and teenage pregnancies. This also contributes to increasing teenage pregnancies, especially in Africa where about 14 million teenage pregnancies occur each year.26 It has also been estimated in sub-Saharan Africa that between 10% and 79% of all pregnancies in women below 20 years of age are described as unwanted.26 This suggests the need for youth empowerment on issues of reproductive health.

Females were found in our study to have initiated sexual activities early than their male counterparts. Similar findings in almost a decade past were reported by Fatusi and Blum who indicated that though females had early sexual debut than males, many of the adolescents had sexual intercourse even before age 15 years.11 It is however unclear what characteristic of the female adolescent makes them have earlier sexual debut than their male counterparts. Engaging in sexual activities during the adolescent period is mostly for perceived social gains such as recognition and respect from peers. Male adolescents may resort to sexual norms as a way of proofing their masculinity to their friends.27

The kind of home and the presence of both parents at home seem to influence adolescents' sexual behavior. Similarly, studies in other contexts suggest that youth from homes with broken marriages were much more vulnerable to high-risk sexual behaviors than the other adolescents.13 Furthermore, Vikat et al. asserted that girls who do not live with both parents are at higher risk of RSBs than those who live with both parents.14 Therefore, living with single parents significantly exposes the respondents in practicing RSB. These findings underscore the significance of a well-organized and stable family in promoting the reproductive health of adolescents. It could be inferred that adequate and proper parenting may be effective in families where both mother and father are present and playing active roles in the upbringing of their children. For instance, we found that about 90% of the respondents who lived with only their fathers or mothers have ever had sex, while among adolescents who lived with both parents, only 54.5% have ever had sexual intercourse. These findings are parallel to the study by Vundule et al. who in their matched case–control study reported that teenagers not living with their biological father are at a high risk of initiating sex at an early age.16 Nevertheless, our study findings that all respondents who stayed with their father only were engaged in premarital sex disagrees with the study by Prinstein et al. who asserted that in families where the father is not present, there is early initiation of sex since it is the father who can instill discipline and monitor the activities of his children.28 This difference may be due to differences in cultural values. In Africa, men are regarded as the family heads and breadwinners for the family for which reason they are constantly out of home working to provide for their families. It is therefore most likely that fathers will always be out of home and not have ample time for their children and consequentially leaving them to their peers. The difference, however, reinforces the impact of the presence of both father and mother in adolescents' sexual behavior. Family structures therefore can have a diverse influence on the sexual behavior of the adolescent. For instance, Slap et al. reported that students from a polygamous family structure are more likely to engage in sexual activity than students from a monogamous family structure.15 The assertion was that polygamous families and families without the father present mostly are unable to meet the complex basic economic and social needs of the adolescent.

Outside of the home environment, the sexual behaviors of adolescents are greatly influenced by peers and the perceived benefits of engaging in sexual intercourse.Some youth believe that engaging in sexual activities increases their social status and respect among their peers and these perceived social benefits increases their chances of adapting sexual behaviors dictated by their peers.29,30 Youth who associate themselves with friends who are sexually experienced and frequently communicate about sex have a higher chance of engaging in sexual norms with the intention of reaping the benefits being told by friends.31 This might be suggestive why most of the respondents in our study who have had sex blamed it on peer influence. This points out to the fact that friends of adolescents should never be ignored when making attempts to promote reproductive health in the community. Therefore, parents, health-care workers, and guardians should provide counseling to the youth regarding their choice of friendships. Parents should also start sex education early enough at homes before teenagers get to learn issues of sex from their peers.11,32 Despite parents' knowledge on the importance of sex education, African parents see the practice as a difficult tax due to cultural beliefs and norms.33 Thus, the early introduction of sexual education is perceived as detrimental rather than helping the adolescent to overcome sexual and reproductive health issues.33 For instance, studies in Ghana and Kenya have asserted that many parents did not receive sexuality education from their parents and this makes it even more difficult for them to explain some sex terminologies to their children.34,35 However, some parents in Ghana preferred discussing sex issues with their daughters as a way of protecting them from unwanted pregnancies.34 It therefore illustrates that parents themselves need to be educated on reproductive health issues and be encouraged to communicate with their children on issues of sexual and reproductive health. Our study revealed that friends and the mass media are important sources of information on sexuality to adolescents. Studies in other contexts have noted that exposures to pornographic movies, pictures, and other sexually exciting print content puts students at higher risk of practicing RSB.18,19,36 It is therefore not surprising that our study participants who were involved in watching pornographic films were more likely to engage in adolescence premarital sex. Promoting reproductive health of the adolescent therefore requires a public decorum on what sort of information, pictures, and videos is put in the public domain by the mass media. Exposure to sexy media contents heightens the curiosity of the youth making them want to experiment what they have watched or seen, and this makes them liable to premarital sex and its attendant sequelae.37

CONCLUSION

Adolescents are initiating sexual intercourse very early in life. This happens in both males and females. It is a worrisome act and should be of concern to all public health officials since it may come with high costs including HIV infections, teenage pregnancy, and school dropouts. The replacement of parental role by peers in sexual communication leads to early initiation of sexual intercourse. Therefore, proper timing of parent–child sexual communication may have a role in reducing higher risk sex. The study findings imply that adolescents are initiating their first sex very early in life, and this is related to the numerous exposures to sexual materials on social media and peer influence. Public health officials and stakeholders could initiate policy frameworks to regulate the type of information that is made accessible to children and adolescents by the media networks. Furthermore, parents and school teachers should be empowered with sex information and encouraged to educate pupils on sexual and reproductive health. This will prevent adolescents from seeking such information from their peers. However, it is recommended that further studies should be done to determine how parent–child sexual communication could delay the sexual debut of the adolescent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Recognizing Adolescence. 2014. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 29]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page1/recognizing-adolescence.html .

- 2.Uchudi J, Magadi M, Mostazir M. A multilevel analysis of the determinants of high-risk sexual behaviour in sub-Saharan Africa. J Biosoc Sci. 2012;44:289–311. doi: 10.1017/S0021932011000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen SA, Grunbaum JA, Whalen L, Eaton D, et al. Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madise N, Zulu E, Ciera J. Is poverty a driver for risky sexual behaviour? Evidence from national surveys of adolescents in four African countries. Afr J Reprod Health. 2007;11:83–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abels MD, Blignaut RJ. Sexual-risk behaviour among sexually active first-year students at the University of the Western Cape, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2011;10:255–61. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2011.626295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silas J. Poverty and Risky Sexual Behaviors: Evidence from Tanzania. Maryland, USA: ICF International Calverton; 2013. [Last accessed on 2020 Apr 28]. Available from: http://pubs/pdf/WP88/WP88.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Adolescents and Youths. Switzerland: Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sawyer SM, Afifi RA, Bearinger LH, Blakemore SJ, Dick B, Ezeh AC, et al. Adolescence: A foundation for future health. Lancet. 2012;379:1630–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephenson R, Simon C, Finneran C. Community factors shaping early age at first sex among adolescents in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Malawi, and Uganda. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32:161–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biddlecom A, Awusabo-Asare K, Bankole A. Role of parents in adolescent sexual activity and contraceptive use in four African countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2009;35:72–81. doi: 10.1363/ipsrh.35.072.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fatusi AO, Blum RW. Predictors of early sexual initiation among a nationally representative sample of Nigerian adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:136. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghana Statistical Services. 2010 Population & Housing Census Report: Children, Adolescents & Young People in Ghana. Ghana Statistical Services. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kibombo R, Neema S, Ahmed H. Perceptions of risk to HIV infection among adolescents in Uganda: Are they related to sexual behavior? Afr J Reprod Health. 2007;11:168–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vikat A, Rimpelä A, Kosunen E, Rimpelä M. Sociodemographic differences in the occurrence of teenage pregnancies in Finland in 1987-1998: A follow up study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:659–68. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.9.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slap GB, Lot L, Huang B, Daniyam CA, Zink TM, Succop PA. Sexual behaviour of adolescents in Nigeria: Cross sectional survey of secondary school students. BMJ. 2003;326:15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7379.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vundule C, Maforah F, Jewkes R, Jordaan E. Risk factors for teenage pregnancy among sexually active black adolescents in Cape Town. A case control study. S Afr Med J. 2001;91:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mmari K, Blum RW. Risk and protective factors that affect adolescent reproductive health in developing countries: A structured literature review. Glob Public Health. 2009;4:350–66. doi: 10.1080/17441690701664418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fawole OI, Ajayi OI, Babalola TD, Oni AA, Asuzu AC. Sociodemographic characteristics and sexual behavior of adolescents attending the STC, UCH, Ibadan: A 5 year review. West Afr J Med. 2012;18:165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brieger WR, Delano GE, Lane CG, Oladepo O, Oyediran KA. West African Youth Initiative: Outcome of a reproductive health education program. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29:436–46. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00264-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnusson C. Adolescent girls' sexual attitudes and opposite-sex relations in 1970 and in 1996. J Adolesc Health. 2001;28:242–52. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghana: Ghana Statistical Services. 2010 Population and Housing Census. Summary Report of Final Result. Accra: Ghana: Ghana Statistical Services. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamane T. Statistics, An Introductory Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Harper and Row; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boislard PM, Poulin F. Individual, familial, friends-related and contextual predictors of early sexual intercourse. J Adolesc. 2011;34:289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawoyin OO, Kanthula RM. Factors that influence attitudes and sexual behavior among constituency youth workers in Oshana Region, Namibia. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14:55–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uchudi J, Magadi M, Mostazir M. Social Research Methodology Centre Working Paper: Africa. London, UK: Department of Sociology, City University; 2010. A multilevel analysis of the determinants of high risk sexual behaviour in Sub-Saharan Africa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Worlds Health Organization. Pregnant Adolescents: Delivering on Global Promises of Hope. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendle J, Ferrero J. Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with pubertal timing in adolescent boys. Dev Rev. 2012;32:49–66. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prinstein MJ, Meade CS, Cohen GL. Adolescent oral sex, peer popularity, and perceptions of best friends' sexual behavior. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28:243–9. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widman L, Choukas-Bradley S, Helms SW, Prinstein MJ. Adolescent susceptibility to peer influence in sexual situations. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58:323–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.10.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brechwald WA, Prinstein MJ. Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. J Res Adolesc. 2011;21:166–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sieving RE, Eisenberg ME, Pettingell S, Skay C. Friends' influence on adolescents' first sexual intercourse. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:13–9. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.013.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ali MM, Dwyer DS. Estimating peer effects in sexual behavior among adolescents. J Adolesc. 2011;34:183–90. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sedgh G, Hussain R. Reasons for contraceptive non use among women having unmet need for contraception in developing countries. Stud Fam Plann. 2014;45:151–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baku EA, Agbemafle I, Ktoh AM, Adamu RM. Parents' experiences and sexual topics discussed with adolescents in the Accra Metropolis, Ghana: A qualitative study. Adv Public Health 2018. 2018:pii: 5784902. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mbugua N. Factors inhibiting educated mothers in Kenya from giving meaningful sex-education to their daughters. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1079–89. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martino SC, Collins RL, Elliott MN, Strachman A, Kanouse DE, Berry SH. Exposure to degrading versus nondegrading music lyrics and sexual behavior among youth. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e430–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiao C, Yi CC, Ksobiech K. Exploring the relationship between premarital sex and cigarette/alcohol use among college students in Taiwan: A cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:527. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]