Abstract

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) are on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic. Their mission of providing essential medical care to underserved populations is now even more vital. CrescentCare, an FQHC in New Orleans, evaluated and tested 3366 patients between March 16 and July 2, with an overall rate of 12% SARS-CoV-2 positivity. The clinic's experience demonstrates how to effectively and rapidly integrate COVID-19 programing, while preserving essential health services. Strategies include developing a walk-in COVID-19 testing site, ensuring appropriate clinical evaluation, providing accurate public health information, and advocating for job safety on behalf of our patients.

Keywords: community-health center, COVID-19, COVID-19 ambulatory response, federally qualified health center

NEW ORLEANS has borne a significant burden of health disparities, intensified by Hurricane Katrina, and now faces the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients served by federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) nationally have been especially hard hit by COVID-19, placing the patchwork of community health centers, such as CrescentCare in New Orleans, on the front lines of the pandemic.

New Orleans restructured its health care system post–Hurricane Katrina on a foundation of community health centers to provide high-quality primary care, behavioral health, preventive services, as well as appropriate triage and referrals (DeSalvo et al., 2008). The postdisaster health system relied on this network to transform our health system, firmly rooting it in the communities of New Orleans (Davis et al., 2020; LPCA, 2020). CrescentCare, an FQHC in the city of New Orleans, grew out of this innovative citywide community health commitment. This ethos, enshrined in the FQHC model of care, prepared CrescentCare to effectively confront the COVID-19 pandemic. Expanding and supporting this model are essential for this and future crises (Kishore & Hayden, 2020).

METHODS

The high rate of community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (John Hopkins University of Medicine, 2020; World Health Organization, 2020) led to a rapid response to redesign services to address this pandemic. Implementation of CrescentCare's COVID-19 walk-in clinic, on March 16, was at the forefront of this response. This dedicated site, following expert guidance, ensured access to testing, clinical evaluation, medical triage, public health, and mental health counseling, as well as linkage to supportive services (Fineberg, 2020).

The COVID-19 clinic was accessible to all people 17 years and older, new and existing patients, regardless of insurance coverage. For the first 12 weeks, only those with symptoms were tested and then the clinic expanded to test both symptomatic and asymptomatic members of our community. It was intentionally not a drive-through site, given that our patients required face-to-face evaluation, and many do not own a vehicle. All existing patients received text messages and e-mails directing them to the walk-in site if symptomatic. Three tents were set up at the health center with registration, with nursing and providers donning appropriate personal protective equipment. Only medical providers interacted within 6 ft of patients. They were tested for SARS-CoV-2 with a nasopharyngeal swab in both nostrils; the specimen was stored in viral transport medium. The time to receive results varied through this study period. Initially, results were received within 7 days improving to 2 days, but, recently, results have been delayed again averaging 7 to 10 days. Multiple funding mechanisms, including the CARES Act and private grant support, ensured patients would not pay any out-of-pocket costs for COVID-19 services.

Outreach efforts focused on the most affected members of our community. The clinic coordinated with outreach agencies and church organizations to raise awareness in the African American community. To address the dearth of testing services for Spanish speakers in the city, the clinic engaged local Spanish language radio stations and immigrant advocacy groups to inform of our testing and provide accurate health information. In addition to bilingual radio service announcements, social media and local press informed the community of our services. During the visit and through follow-up phone calls, public health messaging was provided to each patient about the importance of social distancing. Patients new to our clinic were offered primary care telehealth appointments, connected to local health resources, and offered behavioral counseling services when appropriate.

During the pandemic, essential medical services were continued, including same-day appointments for sexually transmitted infection treatment and for people living with HIV who were newly diagnosed or returning to care following disengagement. Rapid point-of-care HIV testing was offered to people presenting for COVID-19 testing. Our needle-exchange program not only continued throughout the pandemic, with a completely new protocol to maintain social distancing and protect staff and clients, but also grew to its highest number, 349 participants, in one afternoon. Those struggling with opiate use disorder were offered COVID-19 testing, reflecting the overlap between the opioid epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic (Alexander et al., 2020), along with their weekly access to naloxone, syringes, and works. With the help of a dedicated case manager, we ensured that those community members released from incarceration due to presumed COVID-19 infection were referred for care at our clinic.

The Advarra Institutional Review Board granted a full waiver of HIPAA authorization and deemed the study exempt. Differences in distribution were evaluated using Pearson's chi-squared test for categorical variables.

RESULTS

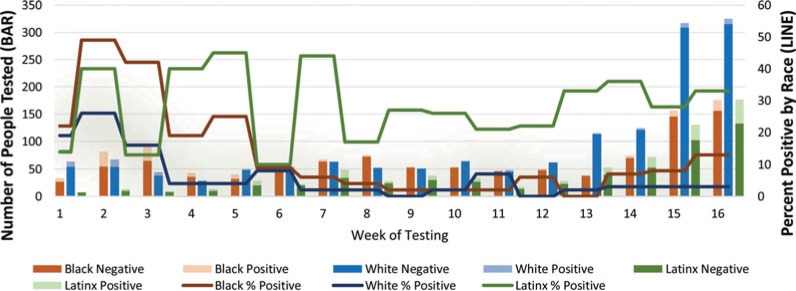

CrescentCare evaluated and tested 3366 patients between March 16 and July 2, with an overall rate of 12% SARS-CoV-2 positivity. Race, as noted nationally (Yancy, 2020), was strongly associated with a positive COVID-19 test at our clinic, with African Americans having 12.7% rate of infection (128/1008), which is 3 times the rate compared with Whites (P < .0001). Latinx patients had a positivity rate of 30% (167/555), 8 times the rate of infection compared with Whites (66/1468) (P < .0001). The rate of infection in both White and Black patients increased initially, with African Americans having a much slower rate of decline than Whites. This was followed by a later spike noted in our Latinx community, which continues to persist (Figure).

Figure.

COVID-19 testing and positivity by race.

All patients were evaluated for clinical symptoms of COVID-19 and triaged on-site for referral to acute or emergency care. Limiting unnecessary utilization of finite hospital-based services was crucial for New Orleans to bend the epidemic curve and a primary goal for CrescentCare. As part of routine follow-up to testing, each patient received a phone call from a provider with the results of his or her test; symptoms were further assessed by phone, and, if concerning, the patient received a daily nurse triage check in. Clients were also educated on warning signs for worsening infection. All patients were instructed to remain in isolation until receipt of results, and those who tested positive were provided the most up-to-date Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance (CDC, 2020). Spanish-speaking clients were called by a bilingual medical provider to ensure accurate and culturally competent care. It was difficult to track if negative patients were hospitalized after the initial call with test results, but those who tested positive received additional phone calls if they were still symptomatic, which allowed us to follow the progression of disease. Of the 406 COVID-19–positive patients, only 21 required hospitalization (5%), with 5 fatalities. Three patients were sent to the emergency department directly from our testing program, and the rest were referred to the emergency department through the coordination of our clinical staff.

Following the expansion of testing for asymptomatic patients, our patient volume increased dramatically. Furthermore, as the New Orleans city testing sites reached their maximum capacity on tests per day, our FQHC became one of the only sources for cost-free testing. The average number of daily tests between March and May was 27 and then rose to 91 tests per day between June 1 and July 2. This increase has been driven by asymptomatic workers whose jobs required a negative test to return to work, people hoping to visit loved ones, and those worried about recent exposures.

Many of our patients are essential workers who reported unsafe and stressful work situations, endangering them and their families. Examples included harassment for being out sick, threats of repercussions for absence, working next to sick colleagues, and refusals to pay workers if they could not document a negative test result. CrescentCare medical providers advocated for patients with those employers whose policies contradicted public health recommendations. Similarly, CrescentCare leadership proactively engaged with small businesses and local places of worship to educate them about appropriate public health measures. Furthermore, as members of our community joined the protests against police violence and structural racism, CrescentCare stood in solidarity by providing access to SARS-CoV-2 testing, public health guidance for demonstrating during a pandemic, and speaking out against the use of tear gas by the police.

DISCUSSION

As the experience of CrescentCare demonstrates, FQHCs are at the front lines of the pandemic and can successfully incorporate COVID-19 programming (National Association of Community Health Centers, 2020). The delayed and uncoordinated federal response to the pandemic underscores the urgency for community health centers to step up and fill in service gaps that are most acute for vulnerable and disenfranchised populations. Our experience confirms the disproportionate burden of infection in Black, undocumented, and working-class communities and the need to advocate for equity in resource allocation. Of specific note, the Latinx community makes up 5% of the New Orleansʼ population and yet they comprised 17% of those we tested and 41% of our positive cases.

Louisiana's expansion of Medicaid was integral for the success of this intervention. More than 50% of patients were insured through Louisiana Medicaid, demonstrating the vital role of Medicaid expansion, especially during this pandemic. Overall, 30% of patients were uninsured, but, strikingly, almost 90% of our Latinx population was uninsured. This high rate of uninsured Latinx patients accessing care at our clinic represents our strong pre-pandemic relationships with immigrant communities. These relationships were essential to ensure safe access to COVID testing since many patients voiced concerns about testing and their immigration status. Our clinic worked closely with Latinx community advocates to ensure patients understood their rights.

The limitations for this study include that this public health intervention was undertaken at a single site in New Orleans and in an ambulatory population that felt well enough to seek out COVID-19 testing at a community health center. These limitations impact the generalizability of our findings.

New Orleans faced historic disruption to its health care system post–Hurricane Katrina, and community health centers nurtured its recovery. The COVID-19 pandemic has strengthened the role of our community health center.

Footnotes

J.H., K.C., and B.A. developed the study design and conceived of the manuscript. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by K.C. and C.T. Clinic coordination was performed by I.B. The first draft of the manuscript was written by J.H., K.C., and B.A., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript.

We thank our incredible patients and the dedicated staff at CrescentCare. You are all heroes!

No author reports any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- Alexander G. C., Stoller K. B., Haffajee R. L., Saloner B. (2020, July 7). An epidemic in the midst of a pandemic: Opioid use disorder and COVID-19. Annals of Internal Medicine, 173(1), 57–58. doi:10.7326/M20-1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, August 10). Criteria for return to work for healthcare personnel with SARS-CoV-2 infection (interim guidance). Retrieved July 3, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/return-to-work.html

- Davis S., Billioux A., Avegno J. L., Netters T., Davis G., DeSalvo K. (2020, October). Fifteen years after Katrina: Paving the way for health care transformation. American Journal of Public Health, 110(10), 1472–1475. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo K., Sachs B., Hamm L. (2008). Health care infrastructure in post-Katrina New Orleans: A status report. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences, 336(2), 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fineberg H. (2020, April 1). Ten weeks to crush the curve. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382(17), e37. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2007263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John Hopkins University of Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center. (2020). Tracking. Retrieved March 14, 2020, from https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map

- Kishore S., Hayden M. (2020). Community health centers and Covid-19—Time for Congress to act. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(8), e54. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2020576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LPCA. (2020). Find a health center. Retrieved May 24, 2020, from https://www.lpca.net/main/for-patients/find-a-health-center

- National Association of Community Health Centers. (2020). National findings of health centersʼ response to COVID-19. Retrieved July 31, 2020, from http://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Health-Center-Response-to-COVID-19-Infographic-7.24.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2020, April 20). Coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) situation report 91. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200420-sitrep-91-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=fcf0670b_4

- Yancy C. W. (2020). COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA, 323(19), 1891. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]