Abstract

Abelmoschus is an economically and phylogenetically valuable genus in the family Malvaceae. Owing to coexistence of wild and cultivated form and interspecific hybridization, this genus is controversial in systematics and taxonomy and requires detailed investigation. Here, we present whole chloroplast genome sequences and annotation of three important species: A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius, and compared with A. esculentus published previously. These chloroplast genome sequences ranged from 163121 bp to 163453 bp in length and contained 132 genes with 87 protein-coding genes, 37 transfer RNA and 8 ribosomal RNA genes. Comparative analyses revealed that amino acid frequency and codon usage had similarity among four species, while the number of repeat sequences in A. esculentus were much lower than other three species. Six categories of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were detected, but A. moschatus and A. manihot did not contain hexanucleotide SSRs. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of A/T, T/A and C/T were the largest number type, and the ratio of transition to transversion was from 0.37 to 0.55. Abelmoschus species showed relatively independent inverted-repeats (IR) boundary traits with different boundary genes compared with the other related Malvaceae species. The intergenic spacer regions had more polymorphic than protein-coding regions and intronic regions, and thirty mutational hotpots (≥200 bp) were identified in Abelmoschus, such as start-psbA, atpB-rbcL, petD-exon2-rpoA, clpP-intron1 and clpP-exon2.These mutational hotpots could be used as polymorphic markers to resolve taxonomic discrepancies and biogeographical origin in genus Abelmoschus. Moreover, phylogenetic analysis of 33 Malvaceae species indicated that they were well divided into six subfamilies, and genus Abelmoschus was a well-supported clade within genus Hibiscus.

Introduction

Family Malvaceae consists of 244 genera and over 4200 species, and most of them are widely distributed in tropics and temperate regions [1]. According to the diverse morphological characteristics, this family could be divided into nine subfamilies, including Sterculioideae, Tilioideae, Malvoideae, Helicteroideae, Grewioideae, Dombeyoideae, Byttnerioideae, Brownlowioideae and Bombacoideae [2]. Abelmoschus is one of important genera in subfamily Malvoideae of family Malvaceae. This genus was previously placed within Hibiscus, and subsequently isolated by taxonomists due to genetic differences [3]. As currently defined, genus Abelmoschus contains 11 species, 4 subspecies and 5 varieties [4], and displays a variable habit, from annual to perennial, herbs to shrubs, and is distributed in Asia, Australia and southwestern Africa [5]. Most members of this genus are economically important plants, and used in agriculture, food and medicines. A. esculentus (okra) and A. caillei are widely cultivated as vegetables due to their tender pods [6–8]. A. manihot is a popular green leafy vegetable and its flowers have been applied in clinical treatment of burns, chronic kidney disease and oral ulcers owing to the flavonoids [9, 10]. A. moschatus, as an aromatic plant, could be suitable for medical or food uses to improve insulin sensitivity [11]. A. sagittifolius also has a long history of medicinal usage, and cadinane sesquiterpenoid glucoside extracted from the stem tubers exhibited antitumor activity [12]. Moreover, antioxidant, antimicrobial, wound healing, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities were also found in Abelmoschus species [13–16]. Seed oil and levels of oleic acid have also been reported in Abelmoschus [3].

Due to coexistence of wild and cultivated form and interspecific hybridization, genus Abelmoschus is controversial in systematics and taxonomy, such as taxonomic position of some Abelmoschus species and the relationships between Abelmoschus species and part of Hibiscus species [8]. In terms of morphological and cytological features, highly variable root, flower and fruit characters of Abelmoschus have been used extensively in classification system [17, 18]. Patil et al. found seed coat sculpturing and seed trichomes could be used as the diagnostic characters for many morphologically closely related species of Abelmoschus [5]. Fluorochrome-binding pattern of nine Abelmoschus species showed polyploidy was an important factor in the chromosome number variation and evolution in this genus [4]. Some researchers also used molecular markers to analyze genetic relationships of Abelmoschus, but most studied focused on genetic diversity within A. esculentus and A. manihot [2, 7, 9, 18, 19], molecular markers were relatively lacking in other species. Thus, new molecular tools were necessary to study the accurate phylogeny in Abelmoschus.

Chloroplast is characteristic organelle in plant cells, and crucial in the photosynthesis and biosynthesis of pigments, amino acids, starch and fatty acids [20, 21]. The chloroplast genome generally has a circular structure with a pair of inverted-repeats (IR) regions (further called IRa and IRb), a large single copy (LSC) region and a small single copy (SSC) region. Due to the small size, conserved structure and gene content, it has been applied for resolving phylogenetics, evolution, taxonomic issues, population genetics and environmental adaptability [22]. Although chloroplast genome sequences of Abelmoschus esculentus has been deposited in GenBank (NC_035234.1) [23], there are no systematic, comprehensive and comparative studies of chloroplast genome in Abelmoschus.

In this study, three chloroplast genomes of A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius were sequenced and compared with the chloroplast genomes of A. esculentus (NC_035234.1) and related species in Malvaceae. Apart from gene content and structure organization, comparative studies were conducted to identify mutational hotspots in Abelmoschus, and a phylogenetic tree of 33 species in family Malvaceae were constructed. These results will be useful in developing molecular markers for resolving taxonomic issues of Abelmoschus, and elucidating the evolutionary and phylogenetic relationships in the family of Malvaceae.

Materials and methods

Plant material, DNA isolation and sequencing

The fresh leaves of A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius were collected from the experimental field of Guangdong academy of agricultural sciences (Guangzhou, China). All samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately and stored at −80°C. Total DNA was extracted by Plant DNA Isolation Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). Paired-end (PE) library was constructed according to protocol of Illumina manual (San Diego, CA, USA), and then it was run on an Illumina NovaSeq platform (Genepioneer Biotechnologies, Nanjing, China) with PE150 sequencing strategy and 350 bp insert size.

Chloroplast genome assembly and annotation

Raw reads of three Abelmoschus species were filtered using the software NGSQCToolkit V2.3.3. In order to reduce the complexity of sequence assembly, filtered reads were compared with the chloroplast genome database built by Genepioneer Biotechnologies (Nanjing, China) using Bowtie2 V2.2.4, and sequences on the alignment was used as the chloroplast genome sequence of samples [24]. Seed sequence was obtained by software SPAdes v3.10.1, and contigs was acquired by kmer iterative extend seed. Then, the contigs were connected as scaffolds by SSPACE v 2.0, and gaps were filled using Gapfiller v2.1.1 until the complete chloroplast genome sequence was recovered. Finally, quality control was adopted to ensure the accuracy of assembly results with the reference genome of A. esculentus (NC_035234.1).

The coding sequences and ribosomal RNA (rRNA) were obtained using software BLAST V 2.2.25 and HMMER V3.1 b2 after compared with the chloroplast genome database in National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Aragorn V1.2.38 software was used for transfer RNA (tRNA) prediction, then tRNA annotation information of chloroplast genome was obtained. Chloroplast genome maps were made by OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW).

Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) and RNA editing sites

RSCU analysis of A. moschatus, A. manihot, A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus (NC_035234.1) was determined using MEGA v7.0, and value of RSCU greater than one was considered to be a higher codon frequency. The putative RNA editing sites were analyzed by PREP-cp (http://prep.unl.edu/) with default parameters [25].

Simple Sequence Repeats (SSRs) and repeat sequences

The comparison of SSRs within four Abelmoschus species were identified using MISA (MIcroSAtellite identification tool) v1.0 with 8 for mononucleotide repeats, 5 for di- and 3 each for tri-, tetra-, penta- and hexanucleotide repeats. Software vmatch v2.3.0 was used to identify forward (F), reverse (R), palindromic (P), and complementary (C) repeats with minimum repeats size ≥30 bp and sequence similarity of 90%.

Genetic divergence, substitutions and insertion/deletions (Indels) analysis

MAFFT ((Multiple Alignments using Fast Fourier Transform) V7.427 was used to perform global alignment of protein-coding genes, intergenic spacer (IGS) regions, and intron regions of complete chloroplast genome among A. moschatus, A. manihot, A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus (NC_035234.1), and the value of genetic divergence (π) was calculated using DNAsp5. With the reference genome of A. moschatus, different types of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and Indels were determined in Abelmoschus using MAFFT program.

Analysis of non-synonymous (Ka)/synonymous (Ks), IR scope and collinearity

In order to analyze substitution rates of Ka/Ks, the protein-coding genes of A. moschatus (as reference) was compared with A. manihot, A. sagittifolius, A. esculentus, and three related species in Malvoideae: Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (NC_042239.1), Althaea officinalis (NC_034701.2) and Gossypium hirsutum (NC_007944.1). Protein-coding genes of all this species were aligned with A. moschatus and analysed by MAFFT V7.427, and the Ka/Ks value was calculated by the KaKs_calculator 2.0 [26].

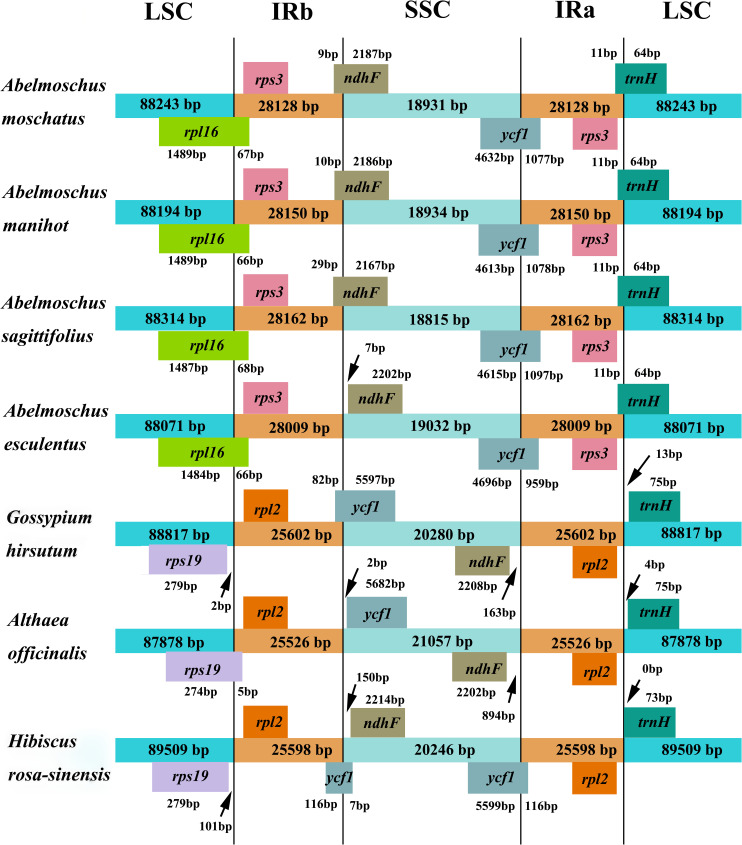

The contraction and expansion of the IR boundaries among the above seven species in Malvoideae were visualized between the four regions of the chloroplast genome (LSC/IRb/SSC/IRa) by Geneious R8.1. Meanwhile, the analysis of chloroplast sequence homology and collinearity was performed by Mauve software.

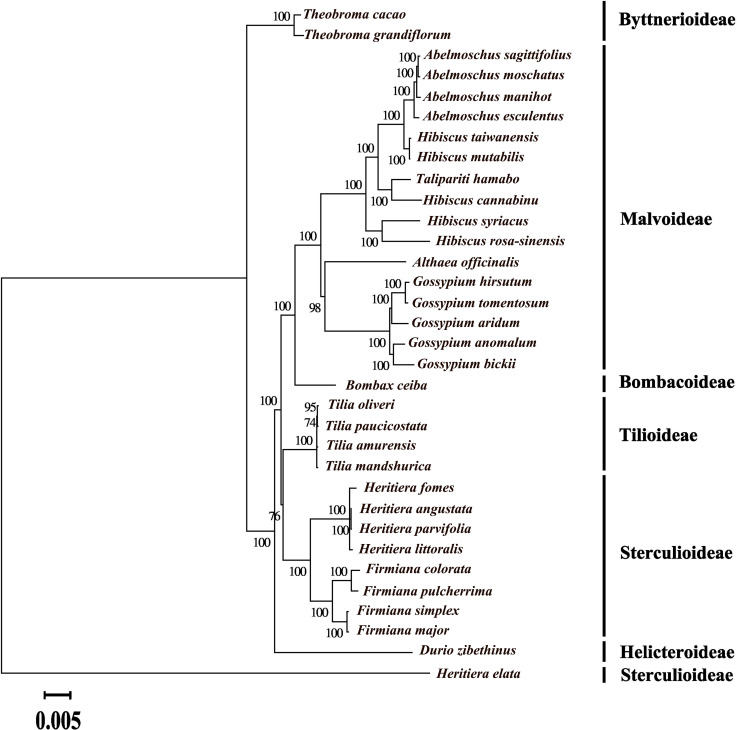

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the chloroplast genomes of A. moschatus, A. manihot, A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus, along with related 29 species within the same family of Malvaceae. Their accession numbers were listed in S1 Table. All chloroplast genome sequences were aligned through MAFFT V7.427, and Indels were removed by TrimAl (V1.4.rev15), then phylogenetic tree was constructed under maximum composite likelihood method (GTRGAMMA model and bootstrap = 1000) using RAxML v8.2.10.

Results

Characterization of chloroplast genomes in Abelmoschus species

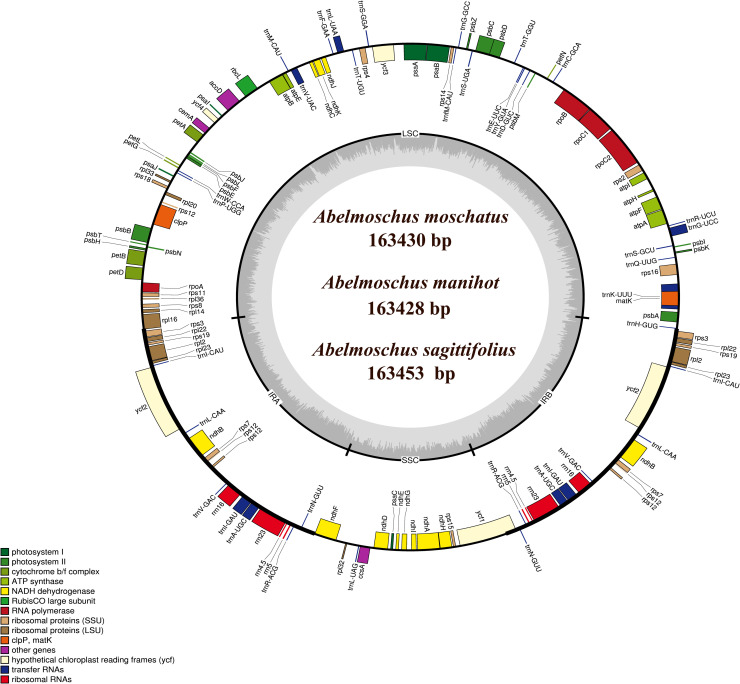

Illumina Novaseq 6000 produced a total of 25,192,038, 19,864,607 and 21,300,029 paired-end (150bp) clean reads for A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius, with average organelle coverage 4470, 1888 and 3194, respectively. Chloroplast genome size was ~163 kb in Abelmoschus species, including a pair of IR regions separated by a LSC region and a SSC region (Fig 1 and Table 1). The GC content of Abelmoschus chloroplast genomes was ~36%, and the LSC, SSC and IR regions had similar content in four species, with ~34%, ~31% and ~41%, respectively.

Fig 1. Chloroplast genome map of three Abelmoschus species.

Genes shown outside the circle are transcribed clockwise and those inside counterclockwise. Genes belonging to different functional groups are color-coded.

Table 1. Summary statistics for the chloroplast genomes of Abelmoschus species.

| Genome features | A. moschatus | A. manihot | A. sagittifolius | A. esculentus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genome size (bp) | 163430 | 163428 | 163453 | 163121 |

| LSC size (bp) | 88243 | 88194 | 88314 | 88071 |

| SSC size (bp) | 18931 | 18934 | 18815 | 19032 |

| IR size (bp) | 28128 | 28150 | 28162 | 28009 |

| Number of genes | 132(112) | 132(112) | 132(112) | 131(111) a |

| Protein genes [unique] | 87(78) | 87(78) | 87(78) | 87(78) |

| tRNA genes [unique] | 37(30) | 37(30) | 37(30) | 36(29) a |

| rRNA genes [unique] | 8(4) | 8(4) | 8(4) | 8(4) |

| Duplicated genes in IR | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| GC content (%) | 36.71 | 36.70 | 36.69 | 36.74 |

| GC content in LSC (%) | 34.47 | 34.48 | 34.45 | 34.55 |

| GC content in SSC (%) | 31.55 | 31.55 | 31.59 | 31.48 |

| GC content in IR (%) | 41.95 | 41.93 | 41.90 | 41.97 |

a Data was from the A. esculentus chloroplast genome (NC_035234.1), and the number of genes should add one because gene trnH-GUG was not annotated.

The chloroplast genome of Abelmoschus species contained 132 genes (112 unique genes), including 87 protein-coding, 37 tRNA, and 8 rRNA genes (Table 2). Gene trnH-GUG was not annotated in the original annotation of A. esculentus (NC_035234.1). There are 20 duplicated genes, including four rRNA genes and 16 other genes (ndhB, rpl2, rpl22, rpl23, rps12, rps19, rps3, rps7, trnA-UGC, trnI-CAU, trnI-GAU, trnL-CAA, trnN-GUU, trnR-ACG, trnV-GAC and ycf2), and all of them repeats once. Moreover, 18 intron-containing genes were found (Table 3), fifteen of which contained one intron and three of which (ycf3, trnV-UAC and clpP) contained two introns. Except the genes of trnA-UGC, trnI-GAU, ndhB, petD and petB, thirteen other genes had different fragment sizes of intron. The complete chloroplast genome has been submitted to NCBI under GenBank accession numbers MT890968 for A. moschatus, MT898000 for A. manihot, and MT898001 for A. sagittifolius.

Table 2. List of annotated genes in the chloroplast genomes of A. moschatus, A. manihot, A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus.

| Category | Gene group | Gene name |

|---|---|---|

| Photosynthesis | Subunits of photosystem I (5) | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ |

| Subunits of photosystem II (15) | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, psbZ | |

| Subunits of NADH dehydrogenase (12) | ndhA*, ndhB*(×2), ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhF, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | |

| Subunits of cytochrome b/f complex (6) | petA, petB*, petD*, petG, petL, petN | |

| Subunits of ATP synthase (6) | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF*, atpH, atpI | |

| Large subunit of rubisco (1) | rbcL | |

| Self-replication | Proteins of large ribosomal subunit (12) | rpl14, rpl16*, rpl2*(×2), rpl20, rpl22(×2), rpl23(×2), rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 |

| Proteins of small ribosomal subunit (16) | rps11, rps12**(×2), rps14, rps15, rps16*, rps18, rps19(×2), rps2, rps3(×2), rps4, rps7(×2), rps8 | |

| Subunits of RNA polymerase (4) | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1*, rpoC2 | |

| Ribosomal RNAs (8) | rrn16(×2), rrn23(×2), rrn4.5(×2), rrn5(×2) | |

| Transfer RNAs (37) | trnA-UGC*(×2), trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnG-GCC, trnG-UCC*, trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU(×2), trnI-GAU*(×2), trnK-UUU*, trnL-CAA(×2), trnL-UAA*, trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU, trnN-GUU(×2), trnP-UGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-ACG(×2), trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA, trnS-UGA, trnT-GGU, trnT-UGU, trnV-GAC(×2), trnV-UAC*, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA, trnfM-CAU | |

| Other genes | Maturase (1) | matK |

| Protease (1) | clpP** | |

| Envelope membrane protein (1) | cemA | |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (1) | accD | |

| c-type cytochrome synthesis gene (1) | ccsA | |

| unknown function | Conserved hypothetical chloroplast ORF (5) | ycf1, ycf2(×2), ycf3**, ycf4 |

Gene*: Gene with one intron; Gene**: Gene with two introns; Gene (×2): Number of copies of multi-copy gene.

Table 3. Information on 18 intron-containing genes in the chloroplast genomes of Abelmoschus species.

| Gene | Location | Exon I (bp) | Intron I (bp) a | Exon II (bp) | Intron II (bp) a | Exon III (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| trnK-UUU | LSC | 37 | 2571/2563/2573/2576 | 35 | ||

| rps16 | LSC | 40 | 862/865/870/ 856 | 227 | ||

| trnG-UCC | LSC | 23 | 803/809/804/ 811 | 48 | ||

| atpF | LSC | 145 | 815/815/816/814 | 410 | ||

| rpoC1 | LSC | 432 | 773/774/781/780 | 1626 | ||

| ycf3 | LSC | 124 | 791/790/791/790 | 230 | 809/804/813/ 834 | 153 |

| trnL-UAA | LSC | 35 | 557/558/559/556 | 50 | ||

| trnV-UAC | LSC | 38 | 590/590/590/608 | 35 | ||

| rps12 b | LSC/IRb | 114 | - | 232 | 536/536/536/536 | 26 |

| clpP | LSC | 71 | 676 / 679/ 677/676 | 292 | 943/942/943/948 | 228 |

| petB | LSC | 6 | 812/812/812/821 | 642 | ||

| petD | LSC | 8 | 757/757/757/757 | 475 | ||

| rpl16 | IR | 9 | 1148/1147/1147/ 1142 | 399 | ||

| rpl2 | IR | 391 | 698/698/698/696 | 434 | ||

| ndhB | IR | 777 | 683/683/683/683 | 756 | ||

| trnI-GAU | IR | 37 | 957/957/957/957 | 35 | ||

| trnA-UGC | IR | 38 | 794/794/794/794 | 35 | ||

| ndhA | SSC | 553 | 1119/1120/1119/1119 | 539 |

a The fragment size of intron is in the order of A. moschatus / A. manihot / A. sagittifolius / A.esculentus.

b The rps12 gene is divided into 5'-rps12 in the LSC region and 3'-rps12 in the IR region.

Amino acid frequency, codon usage and RNA editing sites

Four Abelmoschus species showed similarity in amino acids frequency and codon usage. Protein-coding genes comprised 26713, 26705, 26714 and 26717 codons in A. moschatus, A. manihot, A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus, respectively (S2 Table and S1 Fig). Among those amino acids, Leucine was the most encoded amino acid followed by Isoleucine and Serine, while the Cysteine was the least abundant in chloroplast genomes. The use of the codons ATG and TGG, encoding Methionine and Tryptophan, exhibited no bias (RSCU = 1.00) in Abelmoschus. The findings also revealed that most of the amino acids preferred synonymous codons (RSCU >1.00) having A/T at 3′ end, except ATA and CTA encoding for Isoleucine and Leucine, respectively.

Putative RNA editing sites were also determined in four Abelmoschus species. PREP predicted 55 putative RNA editing sites in 24 genes of A. moschatus and A. sagittifolius, 56 putative RNA editing sites in 24 genes of A. manihot, and 62 putative RNA editing sites in 24 genes of A. esculentus (S3 Table). Similar RNA editing sites were found in most genes, however, gene ycf3 was unique to A. esculentus and gene clpP was unique to A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius. The highest number of editing sites were determined in ndhB (12), ndhD (7), matK(5) and petB (5). Genes of ndhD, ndhA and matK varied widely variations among species: In A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius five and one RNA editing sites were found for ndhD and ndhA, while in A. esculentus seven and one RNA editing sites were present, respectively. A. manihot contained one more RNA editing sites in matK gene than other three species. Most conversion occurred at the first and second nucleotides of the codons, and mainly were C/G to A/T conversion. Change of RNA editing sites would produce abundant hydrophobic amino acids, especially Leucine, which was 29 in A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius, and 28 in A. esculentus.

SSRs and repeat sequences

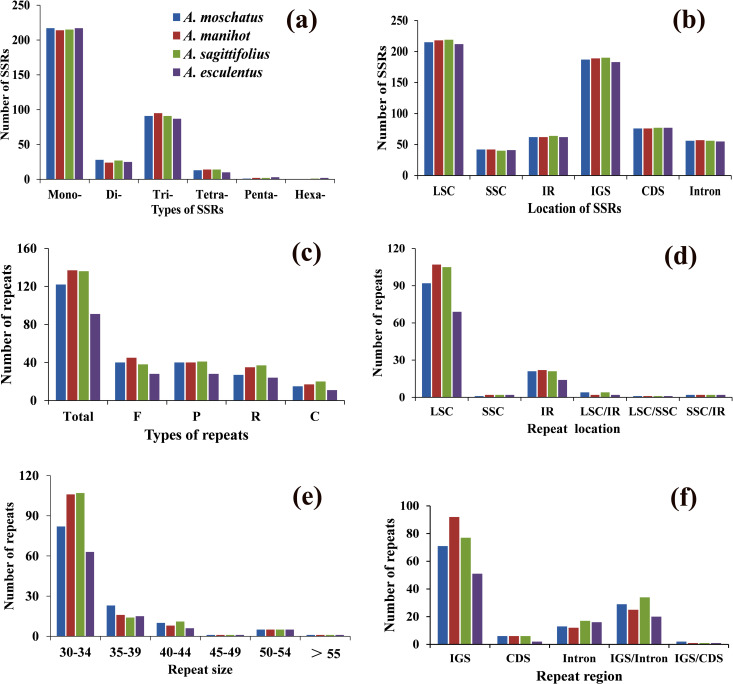

SSRs were detected by MISA software in Abelmoschus (Fig 2A and 2B). A. moschatus contained 350, A. manihot (351), A. sagittifolius (350) and A. esculentus (344) SSRs. The maximum SSRs were mononucleotide and accounted for about 60% of total SSRs, varying in size from 8 to 18 nucleotides. Trinucleotide and dinucleotide SSRs were also abundant and accounted for about 33% of the total SSRs. A. moschatus and A. manihot did not contain hexanucleotides. The A/T and AT/TA were the most abundant mononucleotide and dinucleotide SSRs, respectively. The number of repeats units was also determined for all types of SSRs repeats (S4 Table). About 67% SSRs repeats were found in LSC, 13% in SSC, and 19% in IR. The IGS regions contained the most SSRs, and comprised approximately 58% of the total SSRs.

Fig 2. Comparison of SSRs and repeat sequences among four Abelmoschus species.

(a) Numbers of different types of SSRs; Mono-: mononucleotide, Di-: dinucleotide, Tri-: trinucleotide, Tetra-: tetranucleotide, Penta-: pentanucleotide, Hexa-: hexanucleotide; (b) Location of SSRs in different chloroplast genome regions. LSC: large single copy, SSC: small single copy, IR: inverted-repeat region. IGS: Intergenic spacer regions, CDS: coding DNA sequences, Intron: intronic regions; (c) Different types of repeat sequences. Total: total numbers of all repeats. F: forward repeats, P: palindromic repeats, R: reverse repeats, C: complementary repeats; (d) Number of repeats present in different locations of chloroplast genomes. LSC/IR: one copy of repeat present in LSC and another in IR, LSC/SSC: one copy of repeat present in LSC and another in SSC, SSC/IR: one copy present in SSC and another in IR; (e) Number of repeats in different size. For example, 30–34 represent the numbers of repeats with the size from 30 to 34 bp; (f) Number of repeats in different regions of chloroplast genomes. IGS/Intron: one copy of repeat present in intergenic spacer regions and another in intronic regions. IGS/CDS: one copy of repeat present in intergenic spacer regions and another in coding regions.

Four categories of repeat sequences were also found in Abelmoschus, and there were 486 repeats were present in the chloroplast genomes of four species, 122 in A. moschatus, 137 in A. manihot, 136 in A. sagittifolius and 91 in A. esculentus (Fig 2C–2F). Types of repeats (P, F and R) had similar numbers in each species, but the number of type C is relatively small. The size of repeats was mainly 30–54 bp in four Abelmoschus, and all contained one repeats above 55 bp. Abundant repeats were found in the IGS regions, followed by IGS/Intron regions. Meanwhile, most of the repeats were located in LSC (92, 107, 105, 69), followed by IR (21, 22, 21, 14) and lowest were in SSC (1, 2, 2, 2) in A. moschatus, A. manihot, A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus, respectively. We also found some shared sequences in LSC/SSC (all 1), SSC/IR (all 2), and LSC/IR (2–4) in four species. The complete details of repeat sequences in four Abelmoschus species were also listed in S5 Table.

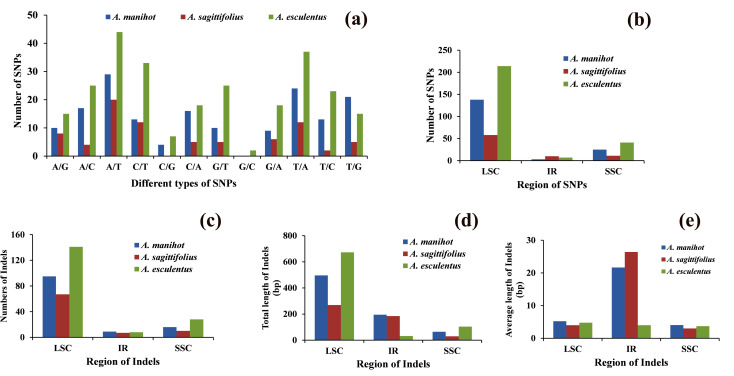

SNPs and Indels in Abelmoschus

Diverse types of SNPs were determined in four Abelmoschus species using A. moschatus as reference. A. manihot, A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus showed 166, 79 and 262 SNPs in complete chloroplast genome, respectively. SNPs of A/T, T/A and C/T were the largest number type among the 12 substitutions in Abelmoschus (Fig 3A and 3B), and most SNPs were located in LSC regions followed by SSC regions. The ratio of transition to transversion was 0.37 for A. manihot, 0.55 for A. sagittifolius and 0.51 for A. esculentus. Furthermore, Indels were also detected in different regions of chloroplast genomes. A total of 120, 84 and 177 Indels were found in A. manihot, A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus, and most of them existed in the LSC regions, but IR regions had the longest Indel average length in A. manihot and A. sagittifolius (Fig 3C and 3E).

Fig 3. Comparison of SNPs and Indels in four Abelmoschus species.

A. moschatus was used as reference for SNPs and Indels detection. (a) The number of different types of SNPs. (b) The number of SNPs in LSC, IR and SSC regions. (c) The number of Indels in LSC, IR and SSC regions. (d) Total length of Indels in LSC, IR and SSC regions. (e) Average length of Indels in LSC, IR and SSC regions. LSC: large single copy, SSC: small single copy, IR: inverted-repeat region.

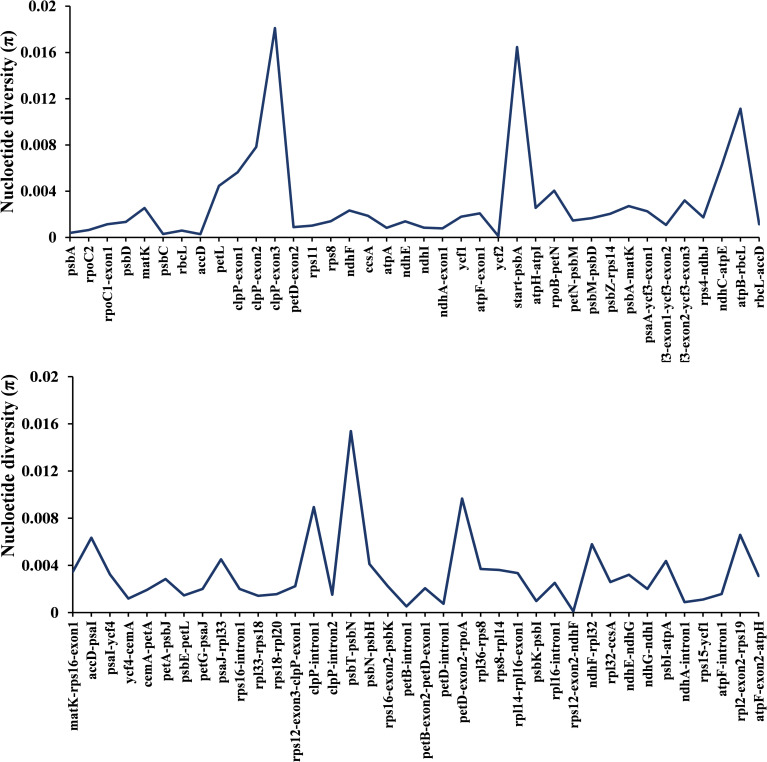

Mutational hotspots in Abelmoschus

Comparative analysis was conducted to identify mutational hotspots of protein-coding genes, IGS and intron regions of chloroplast genome among four Abelmoschus species. The IGS regions had more polymorphic (average π = 0.00432) compared to protein-coding regions (average π = 0.00285) and intronic regions (average π = 0.00269). The nucleotide diversity was ranged from 0.00013 (rps12-exon2-ndhF) to 0.02113 (clpP-exon3) in all the polymorphic containing regions (Fig 4). A total of thirty highly diverse regions (region length ≥200 bp) were listed in Table 4. Most of these mutational hotspots belong to IGS regions, such as start-psbA, atpB-rbcL and petD-exon2-rpoA. Higher nucleotide diversity was also observed for protein coding genes, including 1st and 2nd exon of clpP, 1st intron of clpP, 2nd intron of ycf3, matK, ndhF and 1st exon of atpF.

Fig 4. Nucleotide diversity (π) of different regions among A. moschatus, A. manihot, A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus.

Regions with 0 nucleotide diversity were ignored. The x-axis represents chloroplast genome regions, and the y-axis represents nucleotide diversity.

Table 4. Mutational hotspots in four Abelmoschus species.

| Region | Genetic divergence | Total Number of mutations | Region length |

|---|---|---|---|

| start-psbA | 0.0165 | 23 | 642 |

| atpB-rbcL | 0.0111 | 30 | 1154 |

| petD-exon2-rpoA | 0.0097 | 6 | 266 |

| clpP-intron1 | 0.0089 | 14 | 671 |

| clpP-exon2 | 0.0078 | 5 | 292 |

| accD-psaI | 0.0063 | 11 | 743 |

| ndhC-atpE | 0.0063 | 33 | 2343 |

| ndhF-rpl32 | 0.0058 | 11 | 862 |

| clpP-exon1 | 0.0056 | 3 | 228 |

| psaJ-rpl33 | 0.0045 | 5 | 475 |

| psbI-atpA | 0.0044 | 24 | 2380 |

| rpoB-petN | 0.0040 | 16 | 1907 |

| rpl36-rps8 | 0.0037 | 4 | 464 |

| matK-rps16-exon1 | 0.0035 | 13 | 1653 |

| psaI-ycf4 | 0.0032 | 3 | 396 |

| ndhE-ndhG | 0.0032 | 2 | 267 |

| ycf3-intron2 | 0.0032 | 6 | 802 |

| atpF-exon2-atpH | 0.0031 | 4 | 597 |

| petA-psbJ | 0.0028 | 6 | 1155 |

| psbA-matK | 0.0027 | 4 | 631 |

| rpl32-ccsA | 0.0026 | 7 | 1267 |

| atpH-atpI | 0.0026 | 7 | 1169 |

| matK | 0.0025 | 9 | 1515 |

| rpl16-intron1 | 0.0025 | 6 | 1132 |

| ndhF | 0.0023 | 12 | 2196 |

| psaA-ycf3-exon1 | 0.0023 | 5 | 948 |

| rps16-exon2-psbK | 0.0022 | 5 | 1023 |

| atpF-exon1 | 0.0021 | 2 | 410 |

| petB-exon2-petD-exon1 | 0.0021 | 1 | 207 |

| psbZ-rps14 | 0.0021 | 5 | 1043 |

IR boundary and collinearity

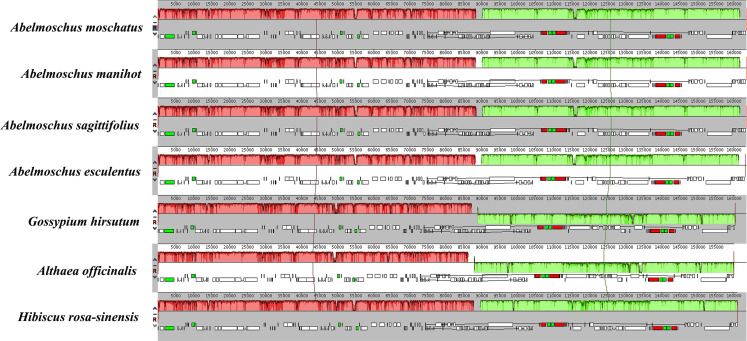

The IR regions were compared among four Abelmoschus species and three closely related species in family Malvaceae (Fig 5). The trnH gene of A. esculentus was reannotated in the junction of IRa/LSC. In four Abelmoschus species, the LSC/IRb boundary was located within the coding region of rpl16 gene, with 66 to 68 bp in the IRb region. The ycf1 gene spanned the boundary of the SSC/IRa region, with 959–1097 bp in the IRa region. The IRb/SSC and IRa/LSC boundaries were crossed by the ndhF gene and trnH gene. However, ndhF gene was all located in SSC region, and 7 bp from the boundary in A. esculentus. The trnH gene had the same fragment size of 64 bp in LSC region of four Abelmoschus. Moreover, the genes of rpl16, ndhF and ycf1 showed different fragment sizes of 1550-1556bp, 2196-2202bp and 5655-5712bp in four Abelmoschus species, respectively. Based on LSC/IRb/SSC/IRa boundaries, the relationships among A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius were closer than A. esculentus. In addition, the pseudogene fragment of ycf1 was 123 bp in the junction of SSC/IRb in Hibiscus rosa-sinensis. The trnH gene was all located in LSC region, with 0-13bp from the boundary in H. rosa-sinensis, Althaea officinalis and G. hirsutum. The rps19 gene was in junction of LSC/IRb in A. officinalis. The chloroplast genomes of 7 species were relatively conserved after aligned by Mauve software, and no rearrangement occurred in gene organization (Fig 6), but the gene layouts within SSC regions of A. officinalis and G. hirsutum were in the opposite orientations compared with H. rosa-sinensis and four Abelmoschus species.

Fig 5. Comparative analysis of boundary regions: IR, SSC and LSC among four Abelmoschus species and three related species in Malvaceae.

Fig 6. Co-linear analysis of seven Malvaceae chloroplast genomes.

The Abelmoschus moschatus genome is shown at top as the reference. Within each of the alignment, local collinear blocks are represented by blocks of the same color connected by lines.

Ka/Ks substitution rate

In this study, we analyzed Ka/Ks rate of A. moschatus compared with to three species in the same genus and three closely related species in family Malvaceae (S6 Table). Eighty-five protein-coding genes were analyzed and thirty-eight of them had an average Ka/Ks rate between 0 to 0.1 in seven species, which indicated these genes were under strong purifying selection pressure in family Malvaceae. In contrast, three genes showed Ka/Ks>1.0, included gene rpl23 in H. rosa-sinensis (1.12), A. officinalis (2.80) and G. hirsutum (1.79), gene clpP in A. esculentus (6.01) and H. rosa-sinensis (3.67), gene ycf1 in A. manihot (1.50) and A. esculentus (2.98). In addition, gene matK had Ka/Ks = 1.0 in A. esculentus, and seven genes (ndhA, ccsA, psbT, rps15, rbcL, accD and ycf2) had Ka/Ks rate between 0.5 and 1.0 in at least one species.

Phylogenetic analysis

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of 33 species in family Malvaceae were constructed based on complete chloroplast genomes after removing the Indels. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that A. moschatus sister to A. sagittifolius, four Abelmoschus species shared a common node with H. taiwanensis and H. mutabilis, and then they came together with other Hibiscus species to form a large group. The species of six different subfamilies were well distinguished with bootstrap values about 100. However, Sterculioideae subfamily was divided into two groups because Heritiera elata did not share a same node with other species in the same genus (Fig 7).

Fig 7. Maximum likelihood phylogenetics tree of 33 species in family Malvaceae based on chloroplast genomes (Indels removed).

Discussion

Genome characteristics of Abelmoschus species and comparison with other species in Malvaceae

Most species in Abelmoschus were economically important plants, but the chloroplast genomes remained relatively limited, with only A. esculentus was sequenced [23]. In this study, three chloroplast genomes of A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius were sequenced and compares with A. esculentus. The sizes of chloroplast genomes ranged narrowly from 163121 to 163453 in four Abelmoschus species, and comparative analyses revealed highly conserved structure and gene. Most angiosperms typically contained 74 to 79 protein-coding genes in chloroplast genomes [27]. In this study, four Abelmoschus species all encoded 78 unique protein-coding genes, and was different with previously reported species of Hibiscus cannabinus and three Firmiana speies in Malvaceae, which contain 79 protein-coding genes [22, 28]. Rabah et al. [23] reported A. esculentus had 29 unique tRNA genes, but the gene trnH-GUG, located at LSC/IRa boundary, was not annotated, so we reannotated this gene for this species. Within the same subfamily, previous studies reported 17, 19 and 18 intron-containing genes in H. cannabinus, H. rosa-sinensis and 12 species of Gossypium, respectively [2, 28, 29], while Abelmoschus harbored 18 intron-containing genes, thirteen out of them had intron length differences among 4 species, and gene trnK-UUU had the longest intron with 2563–2576 bp.

The chloroplast genomes had well collinearity relationship among four Abelmoschus species and three closely related species in Malvaceae, but some differences were detected in terms of the direction of SSC, gene miss and IR expansion and contraction. Gene layouts within SSC region had the same orientations between four Abelmoschus species and H. rosa-sinensis, but A. officinalis and G. hirsutum had the opposite orientations compared with them, and similar phenomenon with different inversions in the LSC region was also found in Chenopodium quinoa and Mangifera indica [23]. The infA gene as a translation initiation factor has been independently lost many times during the evolution of land plants [27, 30], and it also missed in Abelmoschus, but infA showed functional or non-functional in different Malvaceae species, such as H. rosa-sinensis [2].

The border of IR was highly variable region with many nucleotide changes in chloroplast genomes of closely related species. Among four Abelmoschus species, the genes of rpl16, ndhF and ycf1 showed different fragment sizes in the IR boundaries, and the IRb/SSC border was crossed by the ndhF except A. esculentus, in which ndhF had larger gene size and all located in SSC region, this indicated that the relationships among A.moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius were closer than A. esculentus. Moreover, Abelmoschus species showed relatively independent boundary traits compared with the other Malvaceae species. Gene rpl16 was located at the junction of IRb/LSC in Abelmoschus, whereas A. officinalis and G. hirsutum presented rps19 gene crossing the boundary or locating in LSC region, and ten species in different genus of Malvaceae also showed rps19 gene in IRb/LSC [2]. In the IRb region, rps3 was the closest gene to the IRb/LSC boundary in Abelmoschus, but this gene was replaced by the rpl2 in other Malvaceae species. Durio zibethinus was a Malvaceae species with another boundary characteristic, rpl23 (in LSC) and trnI-CAU (in IRb) were the closest genes to the IRb/LSC boundary, and rpl23 and rpl2 had only one copy due to IR expansion and contraction [31]. These results seem to be line with phylogenetic analysis, which indicated that species with more similar boundary traits had closer phylogenetic relationship in Malvaceae.

SSRs and repeat sequences in Abelmoschus

Owing to the advantages of non-recombination, haploidy, uniparental inheritance and low nucleotide substitution rate, chloroplast SSRs markers can be considered as an excellent tool in population genetics and phylogeny analysis [32]. In the current study, mononucleotide SSR in four Abelmoschus species varied in size from 8 to 18 nucleotides, which was different from related species in Hibiscus (7 to 15 nucleotides) and Firmiana (7 to 22 nucleotides) [2, 22]. Both of A. sagittifolius and A. esculentus had six types SSRs, but A. moschatus and A. manihot did not contain hexanucleotides. Most SSRs were distributed in LSC region and intergenic region, and the identified SSRs in Abelmoschus revealed that A/T and AT/TA were the most abundant in mononucleotide and dinucleotide SSRs respectively, which agreed with the majority of plant family [24]. Moreover, repeat sequences was lower in A. esculentus compared with A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius, but they shared similar distribution regions. Abundant repeats were found in the intergenic spacer regions (IGS), followed by intronic region and coding sequences, and the same distribution pattern of repeat sequences were also reported in Hibiscus [2]. These repeat sequences were also crucial in chloroplast genome arrangement and sequence variation of Abelmoschus.

Taxonomic discrepancies and hotspots in Abelmoschus

Previous studies reported that seed shape and trichome structure had major taxonomic importance and proved to be valuable characters for separating taxa of Abelmoschus [5]. SSR markers (mainly in A. esculentus) were also developed from transcriptome data and genomic DNA to investigate genetic relatedness and cross-species transferability [7, 19]. Pfeil et al. analyzed the phylogeny of Hibiscus and the Tribe Hibisceae using chloroplast DNA sequences of ndhF and rp116 intron, and found two tested Abelmoschus species were embedded within Hibiscus [33]. Werner et al. [8] used nuclear internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and chloroplast rpl16 sequences to construct phylogenetic relationships within Abelmoschus, and its relationship with the genus Hibiscus and other related species in Malvaceae, but A. esculentus and A. caillei cannot be distinguished from each other, and genetic diversity within A. esculentus and A. caillei was low. In this study, we listed thirty highly mutational hotspots (≥200 bp) after comparing nucleotide diversity of protein-coding genes, IGS, and intron regions among Abelmoschus, and these hotspots could be used to solve taxonomic discrepancies for genus Abelmoschus. Most mutational hotspots belong to IGS regions, and some hotspots in protein-coding genes had also been commonly used for barcoding markers in related genera, such as matK, rbcL and ndhF [2, 33]. The nucleotide diversity of rpl16 intron was 0.0029, while the thirty hotspots identified in Abelmoschus had nucleotide diversity from 0.0024 to 0.0142, and 23 regions had higher polymorphic than previously reported sequence of rpl16. Interestingly, three exons and one intron of clpP gene all showed high nucleotide diversity, especially the third exon (π = 0.02113, region length = 71bp), and polymorphic region of this gene had been proved to be effective in evaluating the crop types and biogeographical origin of Cannabis sativa [34]. Therefore, all these mutational hotspots provided useful information for subsequent development of chloroplast markers, evolutionary relationships and biogeographical origin.

Phylogenetic relationship in Malvaceae

Phylogenetic tree of 33 species in family Malvaceae were reconstructed using chloroplast genomes without Indels in this study, and they were well divided into six subfamilies, except Heritiera elata which did not share a node with other species in the same genus. Few previous studies referred to the taxonomic position of A. sagittifolius, our phylogenetic tree suggested that A. sagittifolius was closer to A. moschatus than to A. esculentus, which was consistent with the morphological characteristics of pod and flower [12]. Furthermore, genus Abelmoschus was previously included in the genus Hibiscus and later isolated from it [3]. Four Abelmoschus species shared a common node with H. taiwanensis and H. mutabilis, and then they formed a large group with other Hibiscus species located in different branches. These results indicated that Abelmoschus was a well-supported clade within Hibiscus, and agreed with the viewpoint of Werner et al. [8]. Thus, taxonomic treatment of Abelmoschus is an issue that required further discussion. Abelmoschus could be merged with Hibiscus to form a broad genus Hibiscus, or it maintains the taxonomic position of Abelmoschus, but some Hibiscus species need to change their taxonomic position. As more complete chloroplast genomes are sequenced, the chloroplast genome data could be expected to help resolve the deeper branches of phylogeny and complex evolutionary histories in Malvaceae [35].

Conclusions

Three chloroplast genomes of A. moschatus, A. manihot and A. sagittifolius were sequenced and annotated in the present study, and compared with the chloroplast genomes of A. esculentus and related species in Malvaceae. The results revealed the gene number and order, amino acid frequency, and codon usage were similar in Abelmoschus. However, the differences were also found in IR boundaries, intron-containing genes and the number of repeat sequences and SNPs. Abelmoschus species also showed relatively independent IR boundary traits compared with related species in Malvaceae, and identified thirty mutational hotpots might be useful for developing molecular markers and resolving taxonomic discrepancies and biogeographical origin both at genus Abelmoschus and family Malvaceae levels.

Supporting information

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Abelmoschus moschatus (as reference genome) was compared with A. manihot, A. sagittifolius, A. esculentus, and three closely related species in Malvoideae: Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (NC_042239.1), Althaea officinalis (NC_034701.2) and Gossypium hirsutum (NC_007944.1). Eighty-five protein-coding genes were analyzed.

(XLSX)

Data Availability

The complete chloroplast genomes have been submitted to NCBI under GenBank accession numbers of MT890968, MT898000 and MT898001. All other relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Plan Project of Guangzhou (No. 201904010264), the special fund for Scientific Innovation Strategy Construction of High Level Academy of Agriculture Science (No. R2019PY-QY003), Emerging Discipline Team Project of Guangdong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (No. 201806xx) and Provincial Rural Revitalization Project of Guangdong Province (2020KJ148).

References

- 1.Christenhusz MJM, Byng JW. The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa. 2016; 261:201–217. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdullah, Mehmood F, Shahzadi I, Waseem S, Mirza B, Ahmed, et al. Chloroplast genome of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (Malvaceae): Comparative analyses and identification of mutational hotspots. Genomics. 2020; 112:581–591. 10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarret RL, Wang ML, Levy IJ. Seed oil and fatty acid content in okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) and related species. J Agric Food Chem. 2011; 59:4019–4024. 10.1021/jf104590u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merita K, Kattukunnel JJ, Yadav SR, Bhat KV, Rao SR. Comparative analysis of heterochromatin distribution in wild and cultivated Abelmoschus species based on fluorescent staining methods. Protoplasma. 2015; 252:657–664. 10.1007/s00709-014-0712-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patil P, Malik S, Sutar S, Yadav S, Kattukunnel JJ, Bhat KV. Taxonomic importance of seed macro-and micro-morphology in Abelmoschus (Malvaceae). Nord J Bot. 2015, 33:696–707. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abd El-Fattah BES, Haridy AG, Abbas HS. Response to planting date, stress tolerance and genetic diversity analysis among okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench.) varieties. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2020; 67:831–851. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravishankar KV, Muthaiah G, Mottaiyan P, Gundale SK. Identification of novel microsatellite markers in okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench) through next-generation sequencing and their utilization in analysis of genetic relatedness studies and cross-species transferability. J Genet. 2018; 97(Suppl 1):39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Werner O, Magdy M, Ros RM. Molecular systematics of Abelmoschus (Malvaceae) and genetic diversity within the cultivated species of this genus based on nuclear ITS and chloroplast rpL16 sequence data. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2016; 63:429–445. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rubiang-Yalambing L, Arcot J, Greenfield H, Holford P. Aibika (Abelmoschus manihot L.): Genetic variation, morphology and relationships to micronutrient composition. Food Chem. 2016; 193:62–68. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.08.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Z, Tang H, Shao Q, Bilia A, Wang Y, Zhao X. Enrichment and purification of the bioactive flavonoids from flower of Abelmoschus manihot (L.) Medic using macroporous resins. Molecules. 2018; 23:2649 10.3390/molecules23102649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu IM, Tzeng TF, Liou SS. Abelmoschus moschatus (malvaceae), an aromatic plant, suitable for medical or food uses to improve insulin sensitivity, Phytother Res. 2010; 24:233–239. 10.1002/ptr.2918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen DL, Li G, Liu YY, Ma GX, Zheng W, Sun XB. A new cadinane sesquiterpenoid glucoside with cytotoxicity from Abelmoschus sagittifolius. Nat Prod Res. 2018; 33:1–6. 10.1080/14786419.2018.1437427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pritam SJ, Amol AT, Sanjay BB, Sanjay JS. Analgesic activity of Abelmoschus manihot extracts. Int J Pharm. 2011; 7:716–720. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel K, Kumar V, Rahman M, Verma A, Patel DK. New insights into the medicinal importance, physiological functions and bioanalytical aspects of an important bioactive compound of foods ‘Hyperin’: Health benefits of the past, the present, the future. Beni-Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2018; 7:31–42. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jain PS, Bari SB. Evaluation of wound healing effect of petroleum ether and methanolic extract of Abelmoschus manihot (L.) Medik., Malvaceae, and Wightiatinctoria R. Br., Apocynaceae, in rats. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2010; 30:756–761. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan XX, Tao JH, Jiang S, Zhu Y, Qian DW, Duan JA. Characterization and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from the stems and leaves of Abelmoschus manihot and a sulfated derivative. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018; 107:9–16. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.08.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutar SP, Patil P, Aitawade M, John J, Malik S, Rao S, et al. A new species of Abelmoschus Medik. (Malvaceae) from Chhattisgarh, India. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2013; 60:1953–1958. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pravin P, Shrikant S, Venkataraman BK. Species relationships among wild and cultivated Abelmoschus Medik., (Malvaceae) species as reveled by molecular markers. Int J Life Sci. 2018; 6 (1):49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schafleitner R, Kumar S, Lin CY, Hedge SG, Ebert A. The okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) transcriptome as a source of gene sequence information and molecular markers for diversity analysis. Gene. 2013; 517:27–36. 10.1016/j.gene.2012.12.098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W, Zhang C, Guo X, Liu Q, Wang K. Complete chloroplast genome of Camellia japonica genome structures, comparative and phylogenetic analysis. PLOS ONE. 2019; 14(5):e0216645 10.1371/journal.pone.0216645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan C, Du J, Gao L, Li Y, Hou X. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of watercress (Nasturtium officinale R. Br.): Genome organization, adaptive evolution and phylogenetic relationships in Cardamineae. Gene. 2019; 699:24–36. 10.1016/j.gene.2019.02.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdullah, Shahzadi I, Mehmood F, Ali Z, Malik MS, Waseem S, et al. Comparative analyses of chloroplast genomes among three Firmiana species: Identification of mutational hotspots and phylogenetic relationship with other species of Malvaceae. Plant Gene. 2019; 19:100199 10.1016/j.plgene.2019.100199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rabah SO, Lee C, Hajrah NH, Makki RM, Alharby HF, Alhebshi AM, et al. Plastome Sequencing of Ten Nonmodel Crop Species Uncovers a Large Insertion of Mitochondrial DNA in Cashew. Plant Genome. 2017; 10:1–14. 10.3835/plantgenome2017.03.0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong Y, Xiong Y, He J, Yu Q, Zhao J, Lei X, et al. The complete chloroplast genome of two important annual clover species, Trifolium alexandrinum and T. resupinatum: genome structure, comparative analyses and phylogenetic relationships with relatives in Leguminosae. Plant. 2020; 9:478 10.3390/plants9040478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mower JP. The PREP suite: predictive RNA editors for plant mitochondrial genes, chloroplast genes and user-defined alignments, Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:253–259. 10.1093/nar/gkp337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Z, Li J, Zhao XQ, Wang J, Wong GKS, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator: Calculating Ka and Ks through model selection and model averaging. Genom Proteom Bioinf. 2006; 4:259–263. 10.1016/S1672-0229(07)60007-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millen RS, Olmstead R, Adams K, Palmer J, Lao N, Heggie L, et al. Many parallel losses of infA from chloroplast DNA during angiosperm evolution with multiple independent transfers to the nucleus. Plant Cell. 2001; 13:645–658. 10.1105/tpc.13.3.645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng Y, Zhang L, Qi J, Zhang L. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Hibiscus cannabinus and comparative analysis of the Malvaceae family. Front Genet. 2020; 11:227 10.3389/fgene.2020.00227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Q, Xiong G, Li P, He F, Huang Y, Wang K, et al. Analysis of complete nucleotide sequences of 12 Gossypium chloroplast genomes: origin and evolution of Allotetraploids. PLoS ONE. 2012; 7(8):e37128 10.1371/journal.pone.0037128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, dePamphilis CW, Müller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol. 2011; 76: 273–297. 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheon SH, Jo S, Kim HW, Kim YK, Sohn JY, Kim KJ. The complete plastome sequence of Durian, Durio zibethinus L. (Malvaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2017; 2:763–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L, Wang Y, He P, Li P, Lee J, Soltis DE. Chloroplast genome analyses and genomic resource development for epilithic sister genera Oresitrophe and Mukdenia (Saxifragaceae), using genome skimming data. BMC Genomics. 2018; 19:235 10.1186/s12864-018-4633-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pfeil BE, Brubaker CL, Craven LA, Crisp MD. Phylogeny of Hibiscus and the Tribe Hibisceae (Malvaceae) using chloroplast DNA sequences of ndhF and the rp116 intron. Syst Bot. 2002; 27(2):333–350. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roman MG, Houston R. Investigation of chloroplast regions rps16 and clpP for determination of Cannabis sativa crop type and biogeographical origin. Legal Med-Tokyo. 2020; 47:101759 10.1016/j.legalmed.2020.101759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conover JL, Karimi N, Stenz N, Ané C, Grover CE, Skema C, et al. A Malvaceae mystery: A mallow maelstrom of genome multiplications and maybe misleading methods? J Integr Plant Biol. 2019; 61:12–31. 10.1111/jipb.12746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Abelmoschus moschatus (as reference genome) was compared with A. manihot, A. sagittifolius, A. esculentus, and three closely related species in Malvoideae: Hibiscus rosa-sinensis (NC_042239.1), Althaea officinalis (NC_034701.2) and Gossypium hirsutum (NC_007944.1). Eighty-five protein-coding genes were analyzed.

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

The complete chloroplast genomes have been submitted to NCBI under GenBank accession numbers of MT890968, MT898000 and MT898001. All other relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.