Abstract

Background

There are conflicting reports on the association of undercarboxylated osteocalcin (ucOC) in cardiovascular disease development, including endothelial function and hypertension. We tested whether ucOC is related to blood pressure and endothelial function in older adults, and if ucOC directly affects endothelial-mediated vasodilation in the carotid artery of rabbits.

Methods

In older adults, ucOC, blood pressure, pulse wave velocity (PWV) and brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (BAFMD) were measured (n = 38, 26 post-menopausal women and 12 men, mean age 73 ± 0.96). The vasoactivity of the carotid artery was assessed in male New Zealand White rabbits following a four-week normal or atherogenic diet using perfusion myography. An ucOC dose response curve (0.3–45 ng/ml) was generated following incubation of the arteries for 2-hours in either normal or high glucose conditions.

Results

ucOC levels were higher in normotensive older adults compared to those with stage 2 hypertension (p < 0.05), particularly in women (p < 0.01). In all participants, higher ucOC was associated with lower PWV (p < 0.05), but not BAFMD (p > 0.05). In rabbits, ucOC at any dose did not alter vasoactivity of the carotid artery, either following a normal or an atherogenic diet (p > 0.05).

Conclusion

Increased ucOC is associated with lower blood pressure and increased arterial stiffness, particularly in post-menopausal women. However, ucOC administration has no direct short-term effect on endothelial function in rabbit arteries. Future studies should explore whether treatment with ucOC, in vivo, has direct or indirect effects on blood vessel function.

Introduction

The bone derived hormone osteocalcin (OC) is a vitamin K-dependent protein that exists in several biological forms. The post-translational γ-carboxylation of less than three glutamic acid residues produces undercarboxylated osteocalcin (ucOC), which has a low affinity for hydroxyapatite and is predominantly found in circulating blood [1]. In recent years ucOC has been suggested as a mediator of a cross-talk between bone and metabolic outcomes [2]. In humans, higher levels of ucOC are associated with a reduced risk of metabolic syndrome and type II diabetes [3–5]. Similarly, ucOC has been reported to improve glucose regulation, adiposity and insulin sensitivity in animal models [6–8]. However, not all studies are in agreement [9, 10]. Given these findings, it is of interest to investigate whether ucOC is involved in other biological functions within the body [11, 12]. As metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) share common pathological links [13], it is of particular interest to examine the interaction of ucOC with endothelial function and atherosclerosis progression. This is important, not only in the context of CVD, but also because ucOC could be targeted as a future therapy for metabolic diseases.

The association between OC and its isoforms with CVD in humans remains unknown [14, 15]. A number of cross-sectional studies have reported that higher circulating total OC (tOC) is associated with improved vascular health and function [16–18]. Yet, others have reported that higher tOC has adverse [19–21], or even no association [22], with vascular health. However, only a limited number of studies have investigated the role of ucOC in the vasculature. As ucOC is suggested to be the active circulating form of OC, it is particularly important to investigate whether ucOC is associated with vascular function, and if so, whether these effects are beneficial or detrimental.

In animal models, administration of tOC and ucOC in vivo improve blood vessel function. For example, daily tOC (30ng/gram) injections for 12 weeks significantly improved pulse wave velocity (PWV), a measure of arterial stiffness, in rats with induced diabetes mellitus [23]. Daily tOC also enhanced vasodilation ex vivo in the aorta of apolipoprotein E-/- mice [24]. In another study, 30ng/gram of ucOC administered for 10 weeks in female C57BL/6 mice produced an increase in nitric oxide availability, a key vasoactive molecule [25]. While these in vivo studies indicate potential links between OC administration and improvements in vascular health, they also reported concurrent improvements in metabolic outcomes, such as improved glycaemic control and lower adiposity. Therefore, it is unclear whether the improvement in blood vessel function resulted from a direct effect of OC, or an indirect effect from improved metabolic outcomes.

The aims of this study were to a) investigate the association of circulating ucOC levels with endothelial function, arterial stiffness and blood pressure (BP) in older adults via a cross-sectional analysis, and b) examine the direct effect of ucOC on endothelial function in rabbit arteries.

Methods

Human participants

Twenty six healthy, community dwelling post-menopausal women (mean age of 73 years) and 12 older men (mean age of 74 years) participated in this study. Inclusion criteria included adults over 60 years old and women >12 months post-menopause. Exclusion criteria included a current diagnosis of diabetes, a body mass index (BMI) over 40kg/m2, a fracture within the last 3 months or participation in resistance exercise >2 days per week. Participants were on a range of medications to control for hypertension, cholesterol and CVD, however all were stable and controlled for at least 3 months as per their medical records. Each participant received written and verbal explanations about the nature of the study before signing an informed consent document. This study was approved by Melbourne Health and Victoria University Human Research Ethics Committees. The data were collected as part of a larger clinical trial (ACTRN12618001756213).

Blood pressure (BP) and vascular function

Brachial artery systolic BP, diastolic BP and mean arterial pressure measurements were recorded using the non-invasive SphygomoCor-XCEL® (AtCor Medical, Sydney, NSW, Australia) diagnostic system. Two measurements were captured, with the lower of the two readings recorded. If the two BP readings were >6 mmHg apart, a third measure was recorded to ensure a true resting value and the average of the two lowest BP measurements were recorded. Participants were split into groups based on hypertension guidelines; normal (<130mmHg/<80mmHg) n = 7, stage 1 hypertension (130–139mmHg/80-89mmHg) n = 14 or stage 2 hypertension (>140mmHG/>90mmHG) n = 17 [26]. None of the participants with normal BP were taking antihypertensive medication, five of the participants with stage 1 hypertension and 10 of the participants with stage 2 hypertension were taking antihypertensive medication. Arterial stiffness was measured by PWV using the subtraction method, with the thigh cuff placed on the thigh and a tonometer used to measure the carotid artery waveform (SphygomoCor-XCEL®) [27].

Endothelial function was assessed via brachial artery flow mediated dilation (BAFMD) using a high-resolution ultrasound (Terason, LifeHealthcare, New South Wales, Australia) with R wave trigger. Brachial artery diameter was assessed for ~10 seconds at baseline (in duplicate and averaged) and during forearm occlusion. Brachial artery diameter was continuously captured after the occlusion cuff release for ~2 minutes (reactive hyperaemia). Peak change was calculated as the peak percentage change in brachial artery diameter from baseline to immediately following peak hyperaemia [28].

Circulating osteocalcin measurements

Serum samples were taken in the morning following an overnight fast and stored at -80°C until analysis. Serum tOC was measured using an automated immunoassay (Elecsys 170; Roche Diagnostics) [29]. Serum ucOC was measured using the hydroxyapatite binding method, a commonly used, well established method [30]. Each sample was measured once and the inter-assay coefficients of variation were 5.4% and 9.2% for tOC and ucOC, respectively.

Animals

Male New Zealand White rabbits at 12 weeks of age were randomised into either a normal chow diet (n = 7) (Guinea pig and rabbit pellets, Specialty Feeds, Australia) or an atherogenic diet (n = 10) (a normal diet combined with 1% methionine, 0.5% cholesterol and 5% peanut oil (#SF00-218, Specialty Feeds, Australia)) for 4 weeks [31]. This atherogenic diet has previously been reported to cause endothelial dysfunction in rabbits [31, 32]. The rabbits were housed in individual cages on a 12-hour light/dark cycle at 21°C, with access to water and their assigned chow diet ad libitum. At the completion of the 4-week diet, the rabbits were sedated (0.25mg/kg medetomidine) and anaesthetised (4% isoflurane) before exsanguination via severing of the inferior vena cava. The arterial system was immediately flushed with ice cold Krebs solution ((mM) 118 NaCl; 4.7 KCl; 1.2 MgSO4·7H2O; 1.2 KH2PO4; 25 NaHCO3; 1.25 CaCl and 11.7 glucose) and the carotid arteries were carefully dissected and placed in Krebs solution. The animal experiments were approved by the Victoria University Animal Ethics Committee (#14/005) and complied with the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council code for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes (8th edition).

Perfusion myography

The carotid arteries were cleaned of connective tissue and fat, with care taken to avoid damaging the arterial wall and the endothelium. Arterial branches were identified, and the carotid arteries were cut to a length of 15–20mm, ensuring no branches were present. The arteries were placed in individual chambers within a perfusion myography system (Zultek Engineering, Melbourne, Australia). Each artery was immersed in either normal Krebs solution (11mM glucose) or a high glucose Krebs solution (20mM glucose) as previously described [32]. The organ baths were warmed to 37°C and bubbled with 95% oxygen and 5% carbon dioxide and were refreshed every 30 minutes over a 2-hour period with the respective Krebs solution. Subsequently, the arteries were cannulated, and the respective Krebs solution pumped through the artery while pressure transducers monitored the intraluminal pressure of the vessel.

The carotid arteries were constricted with phenylephrine (3x10-7M), which was added intraluminally and extraluminally. Once a stable constriction was achieved, a dose response curve was completed to ucOC (0.3, 3, 30 and 45ng/ml) (Glu13, 17, 20, osteocalcin (1–46) (mouse) trifluoroacetate salt (Auspep, Australia, H-6552.0500)) or to Krebs (control), each concentration was administered internally via the endothelium and separated by 2 minute intervals. The same mouse ucOC has previously been shown to improve relaxation in rabbit arteries [33]. Following the dose response curve a bolus of acetylcholine (ACh) (10-5M) was added internally and two minutes later a bolus of sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (10-5M) externally, to determine the maximal endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent relaxation, respectively. The vasoactive response of the vessels were analysed using the MEDIDAQ software program (MEDIDAQ, Melbourne, Australia). The vasoactivity of the carotid artery was measured as percentage change from the phenylephrine peak pressure and compared to the baseline pressure. Area under the curve (AUC) was calculated as the total relaxation below the phenylephrine plateau caused by the dose response curve, ACh and SNP bolus doses. The endothelium-dependent Emax was considered as the relaxation produced by ACh, and the endothelium-independent Emax was considered as the relaxation produced by SNP.

Statistical analysis

Human data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA, version 22). A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the difference in ucOC concentration when participants were split into groups based on BP levels. Spearman rho correlations were used to examine the correlation between ucOC and measures of vascular function (BP, BAFMD and PWV) in all participants. Spearman partial correlations were used for the additional adjustments of age, BMI or age and BMI, as they are strong influencers of ucOC levels [1, 29].

Animal data were analysed using Graphpad prism (version 7.1, Graphpad software Inc, USA). A one-way ANOVA was used to examine the effect of the ucOC dose response curves in rabbit carotid artery segments. AUC was calculated as the total area of relaxation below the maximum phenylephrine pressure and a one-way ANOVA was used to determine the difference in AUC between the ucOC dose response curves. All data is reported as mean ± SEM and statistical analysis was conducted at the 95% confidence level of significance (p < 0.05). Trends were reported when p = 0.05–0.099.

Results

Human data

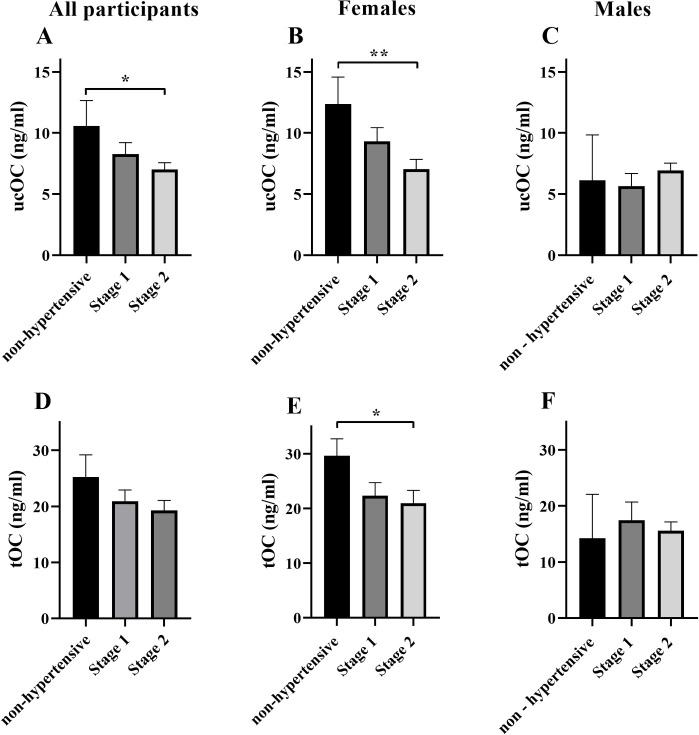

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. In older adults with stage 2 hypertension ucOC was reduced by 34% compared to normotensive individuals (p < 0.05, Fig 1A). When split by sex, ucOC was reduced by 43% (p < 0.01, Fig 1B) and tOC was reduced by 30% (p < 0.05, Fig 1E) in women with stage 2 hypertension compared to normotensive women. There was no difference between groups in older men (p > 0.05, Fig 1C and 1F).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Variable | n | Mean ± SEM |

|---|---|---|

| Participant number (n) [F/M] | 38 [26/12] | |

| Age (years) | 38 | 73 ± 0.96 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 38 | 28 ± 0.59 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 36 | 91 ± 1.58 |

| Currently smoking (n) [%] | 38 | 2 [5] |

| Caucasian ethnicity (n) [%] | 38 | 38 [100] |

| Cholesterol medication (n) [%] | 38 | 13 [34] |

| Antihypertensive medication (n) [%] | 38 | 15 [39] |

| Heart disease medication (n) [%] | 38 | 10 [26] |

| tOC (ng/ml) | 37 | 21 ± 1.31 |

| ucOC (ng/ml) | 37 | 8 ± 0.61 |

| ucOC/tOC ratio | 37 | 0.39 ± 0.01 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 38 | 139 ± 2.53 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 38 | 79 ± 1.43 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 38 | 98 ± 1.74 |

| PWV (m/s) | 34 | 8 ± 0.28 |

| BAFMD–peak dilation (%) | 29 | 4.62 ± 0.44 |

| BAFMD–time to peak dilation (s) | 29 | 58 ± 2.56 |

Abbreviations: BMI; Body mass index, tOC; total osteocalcin, ucOC; undercarboxylated osteocalcin, BP; blood pressure, MAP; mean arterial pressure, PWV; pulse wave velocity, BAFMD; brachial artery flow mediated dilatation.

Fig 1. Concentration of ucOC and tOC based on hypertension category.

ucOC concentration in all participants (A), women (B) and men (C) and tOC concentration in all participants (D), women (E) and men (F) split into groups based hypertension category; non-hypertensive (<130/<80mm/Hg) (women n = 5, men n = 2), stage 1 hypertension (130-139/80-89mm/Hg) (women n = 10, men n = 4) and stage 2 hypertension (>140/>90mm/Hg) (women n = 11, men n = 6). Given the small sample size in each group, particularly for males, the data are not conclusive and further examination of sex specific effects should be explored. All data mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 between groups. Abbreviations: ucOC; undercarboxylated osteocalcin, tOC; total osteocalcin.

Correlation between ucOC and vascular function outcomes

In the unadjusted model, high circulating ucOC was associated with lower systolic BP and PWV with all participants combined (p < 0.05 for both, Table 2). In women only, higher levels of circulating ucOC and tOC was associated with lower systolic BP (p < 0.01). There were trends for associations between lower MAP and PWV with higher levels of ucOC in women (p = 0.05–0.09 for both, Table 2). When adjusted for age, higher ucOC was associated with lower diastolic BP in all participants and with lower systolic BP in women (p < 0.05 for both, Table 2). Increased ucOC levels tended to correlate with both lower DBP and MAP in women after adjusting for age (p = 0.05–0.09 for both, Table 2). Adjusting for BMI, and BMI and age together, removed all associations of ucOC and tOC with BP and PWV outcomes (p > 0.05). There were no significant correlations between ucOC and tOC with BAFMD peak % dilation in any model, and ucOC or tOC was not associated with any vascular function outcome in men (p > 0.05).

Table 2. Correlation of ucOC and tOC with vascular function outcomes.

| ucOC | tOC | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 38) | Women (n = 26) | Men (n = 12) | All (n = 38) | Women (n = 26) | Men (n = 12) | |

| SBP | ||||||

| Model 1 | -0.39* | -0.58** | 0.25 | -0.31^ | -0.4* | 0.18 |

| Model 2 | -0.28 | -0.48* | 0.01 | -0.23 | -0.39^ | 0.07 |

| Model 3 | 0.15 | -0.07 | 0.39 | 0.18 | -0.004 | 0.37 |

| Model 4 | 0.25 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.2 | 0.04 | 0.41 |

| DBP | ||||||

| Model 1 | -0.21 | -0.3 | 0.12 | -0.23 | -0.22 | -0.07 |

| Model 2 | -0.41* | -0.44^ | -0.51 | -0.34 | -0.3 | -0.42 |

| Model 3 | -0.04 | -0.14 | -0.05 | -0.08 | -0.02 | -0.4 |

| Model 4 | -0.13 | -0.14 | -0.75 | -0.09 | -0.02 | -0.58 |

| MAP | ||||||

| Model 1 | -0.2 | -0.35^ | 0.18 | -0.19 | -0.24 | -0.06 |

| Model 2 | -0.32 | -0.44^ | -0.06 | -0.25 | -0.33 | -0.24 |

| Model 3 | 0.12 | -0.05 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.03 | -0.19 |

| Model 4 | 0.09 | -0.01 | -0.42 | 0.1 | 0.04 | -0.22 |

| PWV | ||||||

| Model 1 | -0.41* | -0.41^ | -0.32 | -0.25 | -0.32 | -0.01 |

| Model 2 | -0.18 | -0.26 | 0.25 | -0.14 | -0.26 | 0.4 |

| Model 3 | -0.03 | 0.02 | -0.23 | 0.11 | 0.003 | 0.37 |

| Model 4 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.54 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.76 |

| BAFMD peak % | ||||||

| Model 1 | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| Model 2 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.63 |

| Model 3 | 0.02 | -0.18 | 0.51 | 0.13 | -0.06 | 0.46 |

| Model 4 | 0.05 | -1.14 | 0.29 | 0.14 | -0.04 | 0.64 |

Model 1—unadjusted; Model 2—adjusted for age; Model 3—adjusted for BMI; Model 4—adjusted for age and BMI. Given the small sample size in each group, particularly for males, the data are not conclusive and further examination of sex specific effects should be explored.

*p < 0.05

**p < 0.01

^p 0.05–0.09 ucOC and tOC vs vascular function outcome.

Abbreviations: ucOC; undercarboxylated osteocalcin, tOC; total osteocalcin SBP; systolic blood pressure, DBP; diastolic blood pressure, PWV; pulse wave velocity, BAFMD; brachial artery pulse wave velocity.

Perfusion myography

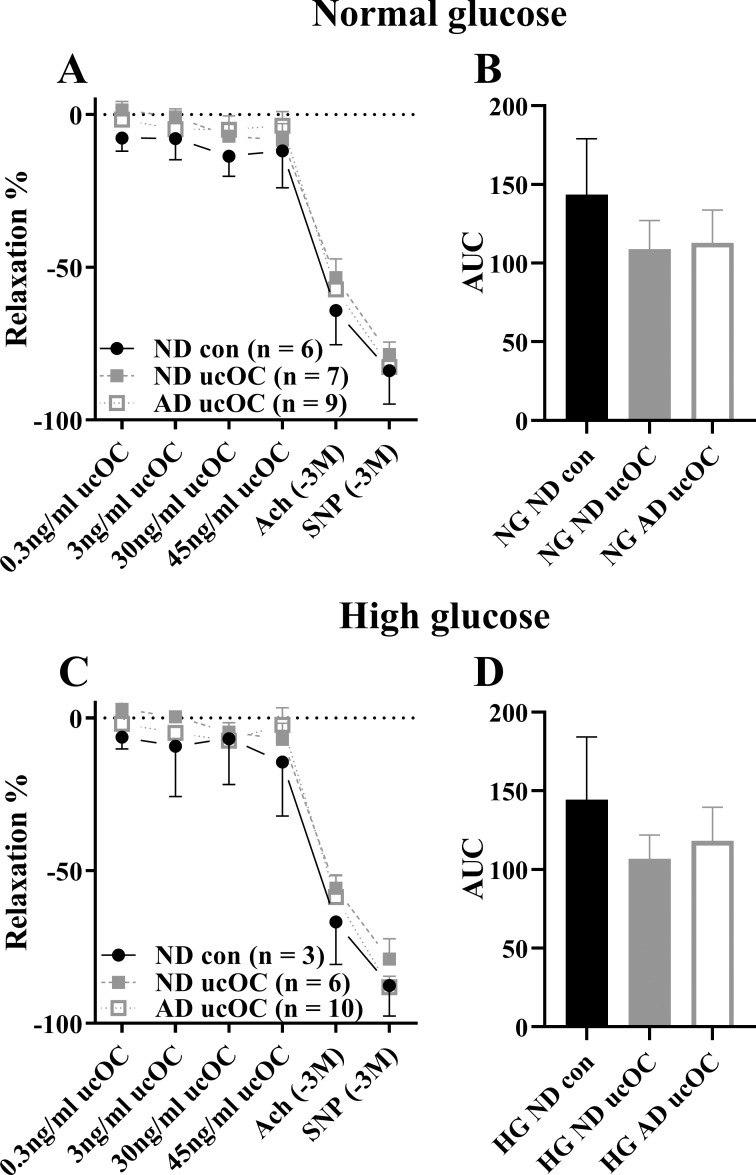

The carotid artery segments from the animals fed the atherogenic diet did not exhibit a reduction in endothelium dependent relaxation in comparison to the arteries from the normal diet fed animals (p > 0.05). The carotid artery vasoactive response from rabbits fed a normal or atherogenic diet and treated ex vivo with ucOC was unaltered in both normal and high glucose environments (p > 0.05, Fig 2A and 2C). The endothelium-dependent (ACh) and endothelium-independent (SNP) Emax were also unaltered following ucOC treatment, in comparison to the control, suggesting ucOC did not enhance the maximal relaxation of the vessel (p > 0.05, Fig 2A and 2C). The AUC was unaltered by ucOC treatment following both the normal and atherogenic diet and incubation in normal and high glucose conditions (p > 0.05, Fig 2B and 2D).

Fig 2. ucOC administration to carotid artery following 2-hour incubation in NG or HG solution.

(A) ucOC dose response curve in carotid artery incubated in NG solution and (B) AUC of dose response curve. (C) ucOC dose response curve in carotid artery incubated in HG solution and (D) AUC of dose response curve. All data mean ± SEM. No significant differences were detected. Abbreviations: ucOC, undercarboxylated osteocalcin; NG, normal glucose media; HG, high glucose media; ND, normal diet; AD, atherogenic diet; Ach, acetylcholine; SNP, sodium nitroprusside.

Discussion

The major findings of the current study are a) in humans, higher circulating ucOC is associated with lower BP and increased arterial stiffness, which is particularly evident in post-menopausal women, and b) ucOC treatment has no beneficial, but also no adverse, effect on carotid artery function from rabbits fed a normal or atherogenic diet, or exposed acutely to normal and high glucose environments.

A number of studies have examined the correlation of tOC with vascular health and function outcomes. It was reported that tOC was lower in men, but not women with hypertension (aged 24–78 years) [34]. Further, in 3,604 middle to older aged men and women, higher levels of tOC were associated with lower PWV in men, but higher PWV in women. However, when controlled for age and menopause status there was no longer an association between tOC and PWV in women [35]. In middle and older aged men, but not post-menopausal women, higher tOC was associated with lower brachial artery PWV and intima media thickness (IMT), even after adjustment for confounding variables including age and BMI [36]. Yet, not all studies are in agreement, as higher tOC levels were associated with increased IMT, carotid plaque and aortic calcification in middle to older-aged women, but not men [19]. Overall, the findings are conflicting, and this appears to be largely driven by the differences between men and women. A major limitation of these studies is that they do not report the concentration of the individual forms of OC, in particular ucOC, which is important as ucOC is the putative bioactive form of the hormone.

Evidence examining the association of ucOC with vascular function is lacking, but crucial, if we are to understand the role of ucOC in CVD, specifically hypertension and atherosclerosis. In the current study we report that higher levels of ucOC are associated with lower BP in post-menopausal women, but not in older men. However, the relatively small sample size of men in the current study means that definitive conclusions cannot be established. However, similar to the current study, a previous study in older men and women (mean age 64 years old), reported that those with a higher cardiovascular risk score had increased MAP and lower circulating ucOC levels [4]. Conflictingly, in 162 community dwelling men (mean age 48 years old) and women (mean age 55 years old), ucOC was not correlated with systolic BP or diastolic BP [37]. The conflicting outcomes may be related to the age difference between the study cohorts, as age is an important factor in determining ucOC levels [29]. Furthermore, hormone variations between sexes and between pre- and post-menopausal women may also explain some of the diverse findings reported. Overall, whether ucOC is a mediator or a marker of CVD processes requires further investigation. In addition, taking into account several factors including sex, age and hormonal status will be important considerations for future studies.

As the association of ucOC with vascular function in humans is unclear, and given the exact biological functions of ucOC are yet to be fully elucidated, examining its bioactive effect on the vasculature in animal models is important. The most commonly used method of examining the vasoactivity of blood vessels ex vivo is via isometric tension analysis. However, in this study, we have utilised a novel perfusion myography system. This technique utilises haemodynamic forces such as shear stress, pressure and pulsatile flow, which are mechanical factors important in the regulation of normal endothelial function, thus creating a more physiological environment [38]. We found that ucOC did not directly influence the vasoactivity of isolated rabbit carotid arteries in either normal or high glucose solutions following an atherogenic or normal diet. A potential limitation of this study is that the atherogenic diet did not cause endothelial dysfunction. This suggests that the carotid artery may be resistant to the development of endothelial dysfunction, as previous studies have reported that the same atherogenic diet caused endothelial dysfunction after 4-weeks in rabbit aorta, iliac and mesenteric arteries [31, 32]. Carotid arteries were used in this study as they lack arterial branches, allowing effective cannulation and perfusion, which would not have been possible in other vessels due to the presence of branches. Notwithstanding, ucOC did not influence vasoactivity when vessels were exposed to a high glucose solution. In support of this, a previous ex vivo study, utilising the isometric tension analysis technique, reported similar findings to the current study. The administration of ucOC (10ng/ml and 30ng/ml) to rabbit aorta following an atherogenic diet or normal diet, with incubation in normal or high glucose solution, did not influence endothelium-dependent or endothelium-independent vasodilation [39]. Whilst another study reported that ucOC caused a slight enhancement in ACh-induced endothelium-dependant relaxation in dysfunctional rabbit aorta following an atherogenic diet, this did not occur after a normal diet, suggesting that ucOC may only function to enhance endothelium-dependent vasodilation in a dysfunctional state [33]. However, this requires further investigation. Overall, whilst we report a correlation between ucOC and BP in post-menopausal women, the ex vivo data indicates that ucOC has minimal direct biological influence on vascular function. There are several potential reasons for these findings. Firstly, ucOC may not act directly on the vasculature, and the associations observed in some studies may be through indirect pathways, such as via improvements in glycaemic control. Secondly, given recent reports, ucOC may not be as biologically active outside of the skeleton as initially suggested [9, 10].

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the relatively small sample size of older adult men means that definitive conclusions on the association of ucOC with vascular function in males cannot be made. Further research should examine in detail the potential association of ucOC with vascular function in females and males, taking into account confounding variables such as age and BMI. Secondly, a number of human participants were on hypertensive medication which may have influenced their BP measurement, highlighting the important role animal models can play in determining any direct effects of ucOC. Finally, due to only male rabbits being studied, the direct effect of ucOC on endothelial function in arteries from female rabbits is unclear.

In conclusion, increased ucOC is associated with lower BP and arterial stiffness in post-menopausal women, but has no direct effect on endothelial function in rabbit carotid arteries. Future studies should explore whether treatment with ucOC in vivo has direct or indirect effects on blood vessel function.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the participants who completed the study for their time and effort.

Data Availability

The Human Ethics approval obtained for this study states that only the investigators will have access to the data. Sharing the data with a wide audience will be a breach of the participants' confidentiality and will not be approved by the Ethics Committee. As such, interested researchers should contact the corresponding author and Ethics Committee if they wish to have access to the data. The corresponding author will then need to receive special approval from the Human Ethics Committee that approved the study to disclose this information. The contact information for the Victoria University Human Ethics Committee is as follows - A/Prof Deborah Zion, Chair of Victoria University Ethics Committee (deborah.zion@vu.edu.au) and VU Research Ethics Committee Secretary (researchethics@vu.edu.au).

Funding Statement

This study was supported by funding from the Rebecca Cooper Medical Research Foundation (IL) (https://www.cooperfoundation.org.au/) and the Tom Penrose Community Service Grant (IL) (https://www.essa.org.au/) from Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Li J, Zhang H, Yang C, Li Y, Dai Z. An overview of osteocalcin progress. J Bone Miner Metab. 2016;34(4):367–79. 10.1007/s00774-015-0734-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin X, Brennan-Speranza TC, Levinger I, Yeap BB. Undercarboxylated osteocalcin: experimental and human evidence for a role in glucose homeostasis and muscle regulation of insulin sensitivity. Nutrients. 2018;10(7). 10.3390/nu10070847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeap BB, Alfonso H, Chubb SA, Gauci R, Byrnes E, Beilby JP, et al. Higher serum undercarboxylated osteocalcin and other bone turnover markers are associated with reduced diabetes risk and lower estradiol concentrations in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(1):63–71. 10.1210/jc.2014-3019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riquelme-Gallego B, Garcia-Molina L, Cano-Ibanez N, Sanchez-Delgado G, Andujar-Vera F, Garcia-Fontana C, et al. Circulating undercarboxylated osteocalcin as estimator of cardiovascular and type 2 diabetes risk in metabolic syndrome patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1840 10.1038/s41598-020-58760-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urano T, Shiraki M, Kuroda T, Tanaka S, Urano F, Uenishi K, et al. Low serum osteocalcin concentration is associated with incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in Japanese women. J Bone Miner Metab. 2018;36(4):470–7. 10.1007/s00774-017-0857-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin X, Parker L, McLennan E, Zhang X, Hayes A, McConell G, et al. Recombinant uncarboxylated osteocalcin per se enhances mouse skeletal muscle glucose uptake in both extensor digitorum longus and soleus muscles. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:330 10.3389/fendo.2017.00330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee NK, Sowa H, Hinoi E, Ferron M, Ahn JD, Confavreux C, et al. Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell. 2007;130(3):456–69. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferron M, McKee MD, Levine RL, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Intermittent injections of osteocalcin improve glucose metabolism and prevent type 2 diabetes in mice. Bone. 2012;50(2):568–75. 10.1016/j.bone.2011.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diegel CR, Hann S, Ayturk UM, Hu JCW, Lim KE, Droscha CJ, et al. An osteocalcin-deficient mouse strain without endocrine abnormalities. PLoS Genet. 2020;16(5):e1008361 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moriishi T, Ozasa R, Ishimoto T, Nakano T, Hasegawa T, Miyazaki T, et al. Osteocalcin is necessary for the alignment of apatite crystallites, but not glucose metabolism, testosterone synthesis, or muscle mass. PLoS Genet. 2020;16(5):e1008586 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levinger I, Brennan-Speranza TC, Zulli A, Parker L, Lin X, Lewis JR, et al. Multifaceted interaction of bone, muscle, lifestyle interventions and metabolic and cardiovascular disease: role of osteocalcin. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(8):2265–73. 10.1007/s00198-017-3994-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi M, Battafarano G, Pepe J, Minisola S, Del Fattore A. The endocrine function of osteocalcin regulated by bone resorption: A lesson from reduced and increased bone mass diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18). 10.3390/ijms20184502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rask-Madsen C, King GL. Vascular complications of diabetes: mechanisms of injury and protective factors. Cell Metab. 2013;17(1):20–33. 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Millar SA, Patel H, Anderson SI, England TJ, O'Sullivan SE. Osteocalcin, vascular calcification, and atherosclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tacey A, Qaradakhi T, Brennan-Speranza T, Hayes A, Zulli A, Levinger I. Potential role for osteocalcin in the development of atherosclerosis and blood vessel disease. Nutrients. 2018;10(10). 10.3390/nu10101426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Confavreux CB, Szulc P, Casey R, Boutroy S, Varennes A, Vilayphiou N, et al. Higher serum osteocalcin is associated with lower abdominal aortic calcification progression and longer 10-year survival in elderly men of the MINOS cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(3):1084–92. 10.1210/jc.2012-3426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu P, Kang D, Wang W, Chen Y, Zhao Z, Zheng H, et al. Serum osteocalcin level is independently associated with the carotid intima-media thickness in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta Endocrinologica (1841–0987). 2014;10(4). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang R, Ma X, Dou J, Wang F, Luo Y, Li D, et al. Relationship between serum osteocalcin levels and carotid intima-media thickness in Chinese postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2013;20(11):1194–9. 10.1097/GME.0b013e31828aa32d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reyes-Garcia R, Rozas-Moreno P, Jimenez-Moleon JJ, Villoslada MJ, Garcia-Salcedo JA, Santana-Morales S, et al. Relationship between serum levels of osteocalcin and atherosclerotic disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2012;38(1):76–81. 10.1016/j.diabet.2011.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanazawa I, Yamaguchi T, Sugimoto T. Relationship between bone biochemical markers versus glucose/lipid metabolism and atherosclerosis; a longitudinal study in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;92(3):393–9. 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okura T, Kurata M, Enomoto D, Jotoku M, Nagao T, Desilva VR, et al. Undercarboxylated osteocalcin is a biomarker of carotid calcification in patients with essential hypertension. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2010;33(1):66–71. 10.1159/000289575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ling Y, Wang Z, Wu B, Gao X. Association of bone metabolism markers with coronary atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab. 2018;36(3):352–63. 10.1007/s00774-017-0841-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang L, Yang L, Luo L, Wu P, Yan S. Osteocalcin improves metabolic profiles, body composition and arterial stiffening in an induced diabetic rat model. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2017;125(4):234–40. 10.1055/s-0042-122138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dou J, Li H, Ma X, Zhang M, Fang Q, Nie M, et al. Osteocalcin attenuates high fat diet-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation through Akt/eNOS-dependent pathway. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2014;13:74 10.1186/1475-2840-13-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kondo A, Kawakubo-Yasukochi T, Mizokami A, Chishaki S, Takeuchi H, Hirata M. Uncarboxylated osteocalcin increases serum nitric oxide levels and ameliorates hypercholesterolemia in mice fed an atherogenic diet. eJBio. 2016;13(1). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carey RM, Whelton PK, Committee AAHGW. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: Synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351–8. 10.7326/M17-3203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Butlin M, Qasem A. Large artery stiffness assessment using SphygmoCor technology. Pulse (Basel). 2017;4(4):180–92. 10.1159/000452448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris RA, Nishiyama SK, Wray DW, Richardson RS. Ultrasound assessment of flow-mediated dilation. Hypertension. 2010;55(5):1075–85. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith C, Voisin S, Al Saedi A, Phu S, Brennan-Speranza T, Parker L, et al. Osteocalcin and its forms across the lifespan in adult men. Bone. 2020;130:115085 10.1016/j.bone.2019.115085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gundberg CM, Nieman SD, Abrams S, Rosen H. Vitamin K status and bone health: an analysis of methods for determination of undercarboxylated osteocalcin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(9):3258–66. 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zulli A, Hare DL. High dietary methionine plus cholesterol stimulates early atherosclerosis and late fibrous cap development which is associated with a decrease in GRP78 positive plaque cells. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90(3):311–20. 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00649.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tacey A, Qaradakhi T, Smith C, Pittappillil C, Hayes A, Zulli A, et al. The effect of an atherogenic diet and acute hyperglycaemia on endothelial function in rabbits is artery specific. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):2108 10.3390/nu12072108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qaradakhi T, Gadanec LK, Tacey AB, Hare DL, Buxton BF, Apostolopoulos V, et al. The effect of recombinant undercarboxylated osteocalcin on endothelial dysfunction. Calcif Tissue Int. 2019;105(5):546–56. 10.1007/s00223-019-00600-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu YT, Ma XJ, Xiong Q, Hu X, Zhang XL, Yuan YQ, et al. Association between serum osteocalcin level and blood pressure in a Chinese population. Blood Pressure. 2018;27(2):106–11. 10.1080/08037051.2017.1408005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yun SH, Kim MJ, Choi BH, Park KC, Park KS, Kim YS. Low level of osteocalcin is related with arterial stiffness in Korean adults: An inverse J-shaped relationship. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(1):96–102. 10.1210/jc.2015-2847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanazawa I, Yamaguchi T, Yamamoto M, Yamauchi M, Kurioka S, Yano S, et al. Serum osteocalcin level is associated with glucose metabolism and atherosclerosis parameters in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(1):45–9. 10.1210/jc.2008-1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi BH, Joo NS, Kim MJ, Kim KM, Park KC, Kim YS. Coronary artery calcification is associated with high serum concentration of undercarboxylated osteocalcin in asymptomatic Korean men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;83(3):320–6. 10.1111/cen.12792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cahill PA, Redmond EM. Vascular endothelium—gatekeeper of vessel health. Atherosclerosis. 2016;248:97–109. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tacey A, Millar S, Qaradakhi T, Smith C, Hayes A, Anderson S, et al. Undercarboxylated osteocalcin has no adverse effect on endothelial function in rabbit aorta or human vascular cells. J Cell Physiol. 2020. 10.1002/jcp.30048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The Human Ethics approval obtained for this study states that only the investigators will have access to the data. Sharing the data with a wide audience will be a breach of the participants' confidentiality and will not be approved by the Ethics Committee. As such, interested researchers should contact the corresponding author and Ethics Committee if they wish to have access to the data. The corresponding author will then need to receive special approval from the Human Ethics Committee that approved the study to disclose this information. The contact information for the Victoria University Human Ethics Committee is as follows - A/Prof Deborah Zion, Chair of Victoria University Ethics Committee (deborah.zion@vu.edu.au) and VU Research Ethics Committee Secretary (researchethics@vu.edu.au).