Abstract

A major challenge in neurobiology in the 21st century is to understand how the brain adapts with experience. Activity-dependent gene expression is integral to the synaptic plasticity underlying learning and memory; however, this process cannot be explained by a simple linear trajectory of transcription to translation within a specific neuronal population. Many other regulatory mechanisms can influence RNA metabolism and the capacity of neurons to adapt. In particular, the RNA modification N6-methyladenosine (m6A) has recently been shown to regulate RNA processing through alternative splicing, RNA stability, and translation. Here, we discuss the emerging idea that m6A could also coordinate to the transport, localisation and local translation of key mRNAs in learning and memory, and expand on the notion of dynamic functional RNA states in the brain.

Keywords: RNA modification, RNA localisation, N6-methyladenosine, learning: memory, synapse

RNA modification: a new frontier in neuroscience

Activity-induced changes in gene expression and protein production are essential for the modulation of synaptic strength and the formation of memory [1]. However, for decades it was thought that protein synthesis occurred solely in the neuronal cell body. When protein synthesis was observed in squid axons [2], and polyribosomes were found in dendritic spines [3], the concept of local protein synthesis was born. Local protein synthesis requires trafficking of specific RNAs to tagged synapses in order to mediate spatially restricted changes in synaptic strength/morphology, and enhance the efficiency of neuronal responses [1, 4–8]. However, despite the fact that RNA localisation and local protein synthesis are now commonly accepted features of neuronal function, several questions remain unanswered. How are particular RNAs selected and marked for transport to distal neuronal compartments? How do they then localise to the synapse? Once localised, are these transcripts translated immediately or are they held in reserve for rapid translation? The answers to these questions may be found in the emerging field of “epitranscriptomics.” To date, over 170 RNA modifications have been identified, although very few have been functionally characterised in the brain [9]. N6-methyladenosine (m6A), the most abundant internal mRNA modification, is dynamically regulated and is critically involved in learning and memory [10–14]. Here we discuss the potential contributions of m6A on RNA localisation and the functional consequences of modified RNA in various neuronal compartments.

RNA localisation mechanisms in the brain

Local translation is dependent on specific RNA transport mechanisms [1]. The current working model for RNA localisation involves recognition of RNA cis-acting elements by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) or trans-acting elements in the nucleus. Cis-acting elements are typically found in the UTRs (untranslated region) of mRNA but differ in their length, sequence, structure, number and position within different transcripts, adding complexity to the potential mechanisms of transport. Small changes in the UTR sequence can alter the secondary structure of mRNAs and the binding of RBPs. Once RBPs bind and translocate from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, they interact with additional molecular motor proteins to form ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) [15]. These RNPs are able to localise/anchor to their destinations and contribute to local translation [16, 17].

Though much of the work on RNA localisation began in neurons [18, 19] because of their polarised morphology, in essence, many if not all cells have spatially restricted regions. Recent studies have identified localised RNA in subcellular compartments like the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria in nonpolarized cells. APEX seq, a method for RNA-sequencing based on proximity labelling of RNA using the peroxidase enzyme, APEX2, profiled nine distinct subcellular locations to produce an “atlas” of localised RNA in human HEK293T cells [20]. Another, technique called chromophore-assisted proximity labelling sequencing (CAP-seq) was developed to profile localised RNA in the ER and mitochondria of HEK293T cells [21]. Though these approaches are yet to be utilised in neurons, they indicate an incredible diversity of localised RNA in different cellular locations. However, despite these demonstrations of RNA localisation, many questions surrounding the specificity of RNA transport in response to stimuli, the factors which influence interactions between RNAs and RBPs, and the temporal dynamics of the functional activation of RNA in distinct neuronal compartments remain unanswered.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A): an abundant internal RNA modification in the brain

The dynamic and reversible RNA modification m6A is regulated by a distinct family of methyltransferases (“writers”), demethylating enzymes (“erasers”) and proteins that interact with m6A-modified RNAs (“readers”) [22–24]. The primary m6A methyltransferase complex, including the enzymes METTL3 and METTL14, preferentially and co-transcriptionally adds a methyl group to the adenosine in a DRACH motif [25]. The m6A modification primarily occurs in the nucleus, therefore it is reasonable to assume that a change in a RNA molecule in the nucleus has the capacity to contribute to its fate in the cytoplasm [26, 27]. However, viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm also have methylated RNA, implying that m6A deposition can also occur in the cytoplasm [28, 29]. The “erasers” of m6A include fat mass and obesity associated protein (FTO) and alkB homologue 5 (ALKBH5). Interestingly, FTO has been shown to be abundantly expressed at the synapse, suggesting the potential for local demethylation [13].

m6A has been implicated in many physiological functions, including gametogenesis, cell fate determination and neuronal function (Table 1). m6A is enriched in the mouse brain during adulthood [30], an observation which paved the way for studying its functional role in neurons. The involvement of m6A in memory consolidation [10, 12, 13], promotion of protein translation in response to stimuli [11], dopaminergic signalling [31, 32], neural differentiation/neurogenesis [33, 34] and stress responses [35] in rodents has since been demonstrated. However, with the discovery of a distinct m6A transcriptome in synapses [36] and the identification of multiple m6A readers that dictate methylated mRNA function in different cellular locations [37], it is plausible to consider a role for m6A in RNA localisation.

Table 1:

m6A in the rodent brain

| Findings | Experimental manipulation | m6A levels | m6A sites/targets | Potential mechanism/pathways | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m6A is enriched in the brain | m6A-seq profiling in different tissues | Increased | mRNA & ncRNA; stop codons & 3’UTR enrichment | microRNA pathways | [30] |

| Region-specific profiling of m6A in RNA in the brain | m6A-seq in cerebellum and cerebral cortex | N/A | CDS of FMRP mRNA targets | FMRP mediated synaptic functions | [113] |

| m6A regulates temporal control of cortical neurogenesis | METTL14 KD | Decreased | mRNAs of transcription factors (i.e. Sox1, Sox2, Emx2,Pax 6) | Cell cycle and neuronal differentiation | [33] |

| m6A enhances neural stem cell renewal | METTL14 KO | Decreased | CBP, p300 | Histone modification regulation | [114] |

| m6A facilitates axonal regeneration | METTL14 KD | Decreased | Atf3, Sox1, Gadd45a, Tet3 | Translation | [89] |

| m6A promotes striatal function and learning via METTL14 | METTL14 KD | Decreased | N/A | Neuronal excitability | [14] |

| m6A via METTL3 enhances hippocampal memory | METTL3 KD | Decreased | IEGs – Arc, Egr1, c-Fos, Npas4, Nr4a1 | IEG induction | [12] |

| m6A regulates cerebellar development via METTL3 | METTL3 cKO | Decreased | Atoh1, Cxcr4, Notch2, Dapk1, Fadd, Ngfr, Grin1, Atp2b3, Grm1, Lrp8 | mRNA stability and alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs | [115] |

| m6A mediates spatiotemporal regulation of RNA in cerebellar development | METTL3 or ALKBH5 KD | Mettl3 KO – Decreased; ALKBH5 KO - increased | Mphosph9 , Opa1, Wdpcp, Letm1 | Transport and localisation | [116] |

| Neuronal stress induces changes in the m6A transcriptome which are mediated by METTL3 and FTO | METTL3 or FTO cKO | Mettl3 cKO – Decreased; FTO cKO - increased | N/A | Transport and localisation | [35] |

| FTOmediated demethylation enhances dopaminergic signalling | FTO inactivation | Increased | Drd3, Kcnj6, Grin1, Syn1 | Translation | [31] |

| m6A enhances fear-memory consolidation in the prefrontal cortex | FTO KD | Increased | Rab33b, Arhgej17, Arhgap39, Crtc1, Gria1 | mRNA stability | [10] |

| m6A enhances neurogenesis and learning and memory processes | FTO KO | Increased | Bdnf, PI3k, Akt1/2/3, S6k1 | Brain derived neurotrophic factor pathway | [117] |

| m6A enhances hippocampal fear-memory formation | FTO KD | Increased | N/A | Localisation | [13] |

| m6A mediates local translation in axons | FTO KD | Increased | Gap43 | Local translation | [87] |

| Demethylatio n via FTO alleviates dopaminergic signalling defects caused by arsenite | FTO KD | Decreased | N/A | Neurotoxic pathways | [118] |

| m6A depletion contributes to dopaminergic neuronal apoptosis | FTO overexpression | Decreased | Grin1, Syn1, Drd3 | Dopaminergic neuron survival pathways | [32] |

| Distinct m6A transcriptome in synapses regulated by m6A reader proteins | YTHDF1 or YTHDF3 KD | N/A | Ptprz1, Sparc1, Slc1a2, Ppp1r9b, Fam171b, Mpeg1, Apc, Apc2 | Localisation and local translation | [36] |

| m6A promotes protein synthesis via YTHDF1 to facilitate hippocampal learning and memory | YTHDF1 KO | N/A | Gria1, Grin1, Camk2a | Local translation | [11] |

| m6A regulates axon guidance via YTHDF1 | YTHDF1 KO/KD | N//A | Robo3.1 | Local translation | [88] |

| m6A reader Prrc2a facilitates oligodendroc yte specification and myelination | Prrc2a KD | N/A | Olig2 | mRNA stability | [119] |

| FMRP identified as a m6A reader to promote nuclear export of RNA in neural differentiation | FMRP KO or METTL14 | FMRP KO – N/A; Mettl14 KO – Decreased | Ptch1, Dll1, Dlg5, Fat4, Gpr161, Spop | Transport and localisation | [34] |

KD: Knock-down

KO: Knock-out

cKO: Conditional Knock-out

IEG: Immediate early gene

RNA binding protein interaction: a potential mechanism of m6A-modified RNA localisation to different subcellular compartments

N6-methyladenosine sequencing (m6A-seq) and methylation RNA immunopreciptation sequencing (MeRIP-seq), which used m6A-antibodies to immunoprecipitate RNA, were used to generate transcriptome-wide m6A maps [30, 38]. These techniques identified m6A in mRNA and non-coding RNA (ncRNA) and showed that the position of m6A is at least partially responsible for its role in regulating mRNA function [19]. The majority of m6A peaks (70%) are located in the 3’-terminal exons, including 3’UTRs, indicating a potential link between m6A and RNA localisation [39]. In unpublished findings from our group, the majority of m6A marks in nuclear transcripts (which are ultimately destined for and functional at the synapse) profiled immediately after fear-extinction learning were found to be located in the 3’UTR (Madugalle et al., unpublished data). In comparison, the m6A tag within the 5’UTR, although less abundant than in the 3’UTR, promotes cap-independent translation by directly binding eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF3), which can recruit the main ribosomal complex for translation without the need for cap binding proteins [40]. m6A-mediated promotion of translation contrasts with the inhibitory effect on elongation in bacteria and human cells in vitro which has been observed for some m6A residues [41, 42]. Intriguingly, however, m6A in the coding sequence (CDS) has been shown to promote translation by recruiting the m6A reader YTHDC2 in HEK293T cells [43]. We have also found that the majority of m6A peaks in transcripts already residing in the synaptic compartment post fear-extinction learning, occur within the CDS (Madugalle et al., unpublished data), suggesting that m6A-dependent translation enhancement in this region could also be a potential mechanism to enable local translation of synaptic mRNAs. Thus, m6A appears to play complex roles in translation, which may depend on its location within a transcript and the proteins with which it interacts.

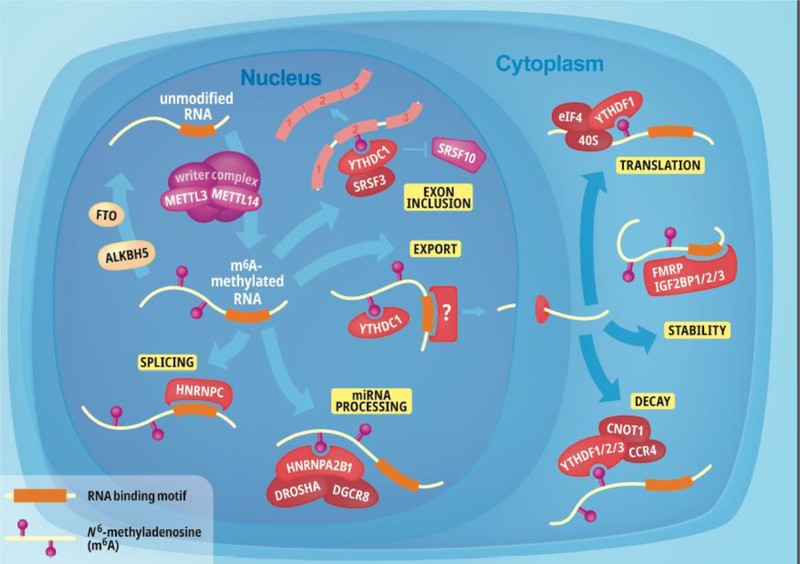

Despite differences in the distribution of m6A across a transcript, the ultimate function of this RNA modification may also be determined by direct or indirect recognition by m6A reader proteins [24] (see Figure 1). The YT521-B homology (YTH) domain family of proteins are direct readers of m6A and include YTHDC1, YTHDC2, YTHDF1, YTHDF2 and YTHDF3. YTHDC1 exerts functional roles of promoting exon inclusion in specific mRNAs by recruiting pre-mRNA splicing factor 3 (SRSF3) and export of mRNAs/selected ncRNAs [44] in an m6A-dependent manner [45], predominantly at the nucleus although YTHDC1 can then shuttle specific RNAs into the cytoplasm. As these experiments were conducted in cells in vitro, it will be vital to replicate the findings in primary neurons to draw conclusions about m6A readers and their context specific function.

Figure 1: Overall functions of m6A.

m6A-modified RNAs have compartment-specific functions. In the nucleus, the m6A methyltransferase complex, which consists of methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), METTL14 and other writer complex proteins such as (Wilms’ tumour-associated protein and KIAA1429), co-transcriptionally adds a methyl group onto the 6th carbon of adenosine. This methyl group can be removed in the nucleus by fat mass and obesity associated protein (FTO) or alkB homologue 5 (ALKBH5). Once modified, the RNA molecule can have various functions mediated by direct or indirect RNA binding proteins (RBPs). Direct readers recognise the m6A modification for microRNA (miRNA) processing (HNRNPA2B1 recognises modified pri-miRNA and recruits DROSHA and DGCR8 proteins to cleave pri-miRNA to pre-miRNA), exon inclusion (whereby YTHDC1 recognises m6A-modified RNA and recruits pre-mRNA splicing factor 3 (SRSF3) but represses (SRSF10) and export (also promoted by YTHDC1). However, indirect readers mediate splicing and export functions by recognising exposed RBP sites on modified RNA. These indirect readers, which are particularly involved in export are continuing to be identified. Once localised to the cytoplasm, m6A-modified RNA has three distinct functions. The YT521-B homology (YTH) domain family of proteins are direct readers of m6A which promote translation (YTHDF1) or decay (YTHDF1/2/3). However, in the cytoplasm, the stability of modified-RNA molecules can also be regulated by Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) or insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP1/2/3).

Once exported out of the nucleus, YTHDF1/2/3 can bind m6A-modified RNA in the cytosol. YTHDF1 promotes protein synthesis by interacting with the translation machinery [46, 47]. In contrast, binding of YTHDF2 to m6A-modified RNA results in the localisation of mRNA from the translatable pool to mRNA decay sites (i.e. processing bodies) [48]. The role of YTHDF3 is not as clear, as YTHDF3 has been reported to promote protein synthesis in synergy with YTHDF1 [49] but also affects the decay of m6A-modified mRNA through interaction with YTHDF2 [50]. Despite these early demonstrations of distinct YTHDF protein functions, it was recently reported that all YTHDF proteins mediate degradation and therefore have redundant roles in m6A RNA metabolism [51]. Again, these findings were derived from studies in cell lines, therefore, a redundant role for YTHDF1/2/3 proteins has yet to be demonstrated in primary neurons.

Indirect readers of m6A exert biological regulation via the phenomenon of the “m6A switch,” in which m6A-dependent changes in RNA structure influence the availability of RBP binding sites. Localisation signals are usually located in the UTRs of transcripts, which enables changes in RNA secondary structure without affecting the protein-coding sequence [24]. Given that m6A is deposited prior to nuclear export of RNA, m6A-modified RNA can undergo nuclear processing (such as splicing and microRNA, or miRNA, processing) which is mediated by HNRNPC, HNRNPG, and HNRNPA2B1 [52, 53]. For example, binding of HNRNPC to modified RNA affects RNA abundance and regulates the splicing of specific mRNAs in HeLa cells [52]. HNRNPG associates co-transcriptionally with RNA polymerase II and uses its low-complexity region (and RNA binding region) to regulate alternative splicing processes [53]. m6A also contributes to miRNA processing, where the RNA binding protein DGCR8 (part of the microprocessor complex) recognises m6A-modified pre-miRNA through interactions with HNRNPA2B1, thereby facilitating the recruitment of DROSHA, which cleaves the RNA duplex to produce pre-miRNA [54, 55]. Theoretically, due to a change in RNA structure states upon modification, any protein which binds near m6A residues can bind to the modified RNA molecules and exert its effect in a specific time and place. Indeed, additional readers of m6A will continue to be found. FMRP, for example, has been shown to modulate neural differentiation via m6A-dependent mRNA nuclear export [34]. Many more RBPs are potentially involved in the localisation of m6A-modified RNA in neurons, the challenge will be to identify them in different neuronal state-dependent contexts.

The state of the RBP itself may also contribute to where RNA molecules are localised and consequently influence how RNA is metabolised. For example, YTHDF proteins have the unique ability to undergo phase separation. All three proteins have a low-complexity region (approximately 30kDa), which contains several prion-like glutamine/proline/glycine-rich domains. These domains interact with each other and cause proteins to undergo phase separation. Intriguingly, prion-like, self-propagating conformational switches have been proposed to explain how memories endure independently of molecular turnover [56]. Early evidence for this idea was demonstrated using cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding (CPEB) protein which exists in prion like conformations, localised to synapses [57]. Interestingly, phase separation also occurs in the presence of m6A, when YTHDF proteins bind to hypermethylated RNAs and form liquid droplets, which can then segregate into stress granules (SGs), processing bodies (P-bodies) or other neuronal RNA granules in cells [25, 47, 58, 59]. Based on these initial findings, perhaps m6A contributes to the trafficking of RNA not only from the nucleus to the cytosol, but also to specific locations in the cytosol, indicating potential for a high degree of specificity. Other RBPs are known to have prion-like states, including TDP-43, FUS, TAF15, HNRNPA1 and HNRNPA2 [60]. Although these proteins are critical for neuronal function, it is not yet known whether they bind directly or indirectly to m6A-modified RNA molecules.

For protein synthesis to be spatially restricted, mRNA must be translationally silenced during transport. As localising complexes include both protein and ncRNA, it is possible that ncRNAs contribute to the translational repression of mRNA that is en route to its final destination in the neuron [61]. For example, the neuron-specific long ncRNA (lncRNA) BC1 is dendritically localised and is a translational repressor [62]. miRNA-134 is also dendritically localised, and inhibits the translation of an mRNA encoding protein kinase, Limk1 [63]. In unpublished findings from our group, a specific splice variant of the lncRNA Gas5 has been found to be highly enriched at the synapse and to interact with key RBPs which are known to be involved in translation and the formation of RNA granules (Liau et al., unpublished data). Determining the full repertoire of RBPs that bind to m6A-modified RNA after synaptic activity, the state of the RBP itself, and the RNP complex composition will provide important insight into how RNA localises to specific locations in the neuron after a learning event.

After localisation, mRNAs can be translationally de-repressed or maintained in a repressed state until specific signals are received. One way in which repressed RNAs can be activated is via the activity of the RNA helicase DDX3. DDX3 is a highly dynamic protein that can shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm [64], and localise to P-bodies [65] under stress. Interestingly, DDX3 is part of an RNA-transporting granule, consisting of CaMKIIa and Arc [66]. This is a particularly interesting finding, as a previous study showed dendritically localised Arc and CaMKIIa in the rat brains associate in smaller, distinct RNA granules with Barentsz and Staufen2 proteins, respectively [67]. These findings indicate heterogeneity in RNP composition but also the possibility of transcripts co-occurring in different RNPs. DDX3 also promotes translation, particularly for mRNAs with structured 5’UTRs (Calviello et al., unpublished data) [68]. For example, Rac1 translation can be activated by DDX3, which modulates neurite development [69]. Interestingly, the ATP domain of DDX3 interacts with ALKBH5, an m6A demethylase, implying that DDX3 could also regulate RNA demethylation [70]. Therefore, it seems reasonable to speculate that DDX3 activity at the synapse could trigger repressed RNAs (potentially through demethylation) for their translational activation. In neurons, to achieve rapid responses, it is highly likely that modified RNAs are stored in so-called “reservoirs” and directed for functional activation by the activity of RNA demethylases or other RBPs in response to environmental cues.

After localisation, m6A-modified RNA may be stored in RNA reservoirs

Sites of RNA storage include SGs, P-bodies and RNA neuronal granules. These membraneless compartments were initially thought to contain only translationally inactive mRNAs, where “quiescent” RNA can be released for translation in response to a stimulus [71]. However, recent studies suggest otherwise, indicating mRNAs can cycle between the cytosol and SGs without undergoing a change in translational status (Mateju et al., unpublished data) [72]. Indeed, it is possible for transcripts to be localised to different neuronal pools. For example, in cortical neurons in vivo, Arc can exist simultaneously in translating and non-translating reservoirs [73]. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider RNA localisation to reservoirs as an active sorting or segregation mechanism that promotes RNA metabolism on an as-needed basis instead of an active silencing mechanism [71]. SGs generally contain polyadenylated transcripts, initiation factors and small ribosomal subunits, and are specifically triggered in response to stress to silence RNAs involved in translation pathways. In contrast, mRNAs recruited to P-bodies are largely deadenylated and contain most enzymes for mRNA degradation. Upon stimulation P-bodies are triggered to degrade transcripts [74]. Both P-bodies and SGs can constantly exchange RNA and protein from these reservoirs with the cytosol [75], which is critical in order for cells such as neurons to rapidly respond to extrinsic cues.

Silencing foci (S-foci) represent another silencing complex that are specific to neurons. S-foci accumulate in the post-synaptic compartment, where they dissolve in response to neural activity, and release CaMKIIa mRNA for translation [76]. Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) in the RBPs of neuronal granules can also contribute to their phase separation properties. In fact, the IDRs of the RNP-granule protein Ataxin-2 are essential for granule assembly and translation-dependent long-term memory processes [77]. In addition, polyribosomes have also been proposed to act as neuronal RNA granules. These granules contain stalled ribosomes with incomplete proteins, packaged in the soma and transported to dendrites for in-demand translation following long-term depression [78]. Despite the identification of RNA reservoirs in neurons, the specificity of RNA movement in and out of these subcellular compartments is less well understood and can potentially be explained by RNA modification, whereby m6A could influence RNA dynamics in different ways in distinct RNA granules.

There is some evidence to suggest that m6A may enhance mRNA partitioning into RNA reservoirs [79]. First, as all three YTHDF proteins contain a low-complexity domain at their N-termini, which is predicted to be a prion-like domain, YTHDF proteins are able to form phase-separated condensates in response to cellular stress and then relocate to granules [80]. This process is facilitated by hypermethylated m6A-containing RNAs, which are translationally repressed following heat shock. Although m6A is required for YTHDF2 to localise RNA to P-bodies, the recruitment of YTHDF proteins to reservoirs has been reported to be independent of their degradation and translational roles for m6A RNA [58]. Whereas YTHDF2 co-localises with both P-bodies and SGs, YTHDF1/3 has been shown to co-localise only with the latter [47]. However, little is currently known about how YTHDF proteins differentiate between RNA molecules destined for RNA reservoirs and their functions outside storage, therefore many issues will need to be resolved in order to fully demonstrate the potential of m6A-modified RNA localised to reservoirs. For example, how do reader proteins recruit m6A-containing RNA to reservoirs independently of their canonical translation/degradation roles? Why are polymethylated RNAs preferentially repressed, and do other m6A reader proteins (such as FMRP) also undergo phase separation?

Other functional states of localised m6A-modified RNA in axons and dendrites

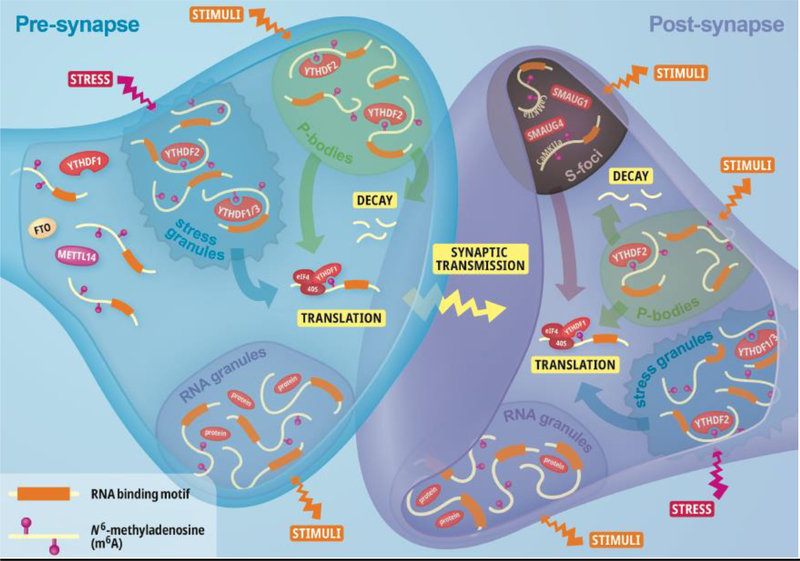

Given the fact that localised RNA can be translationally repressed, it is possible that, once stored within reservoirs in axons and dendrites, RNA will be de-repressed and translated as needed. However, the populations of localised RNAs at these various locations are not necessarily the same. For example, B-actin mRNA is present at basal levels in axon growth cones and is further recruited to these sites upon neurotrophin treatment [81]. In contrast, Arc, CamKIIa, Bdnf and Npas4 localise to dendritic compartments [18, 82–84]. As Arc and CamKIIa are m6A modified [36], it is likely that methylation contributes to localisation of these transcripts and/or promotes their accessibility to the local translation machinery (Figure 2).

Figure 2: m6A functions at the synapse.

In the axon, fat mass and obesity associated protein (FTO), YT521-B homology (YTH) domain family protein 1 (YTHDF1) and methyltransferase-like 14 (METTL14) can direct modified RNA for axonal functions. In pre- and post-synaptic compartments, m6A-modified RNA can be localised to RNA reservoirs such as stress granules, processing bodies (or P-bodies), RNA granules and/or silencing foci (S-foci). Both pre- and post-synaptic compartments contain P-bodies, stress granules and RNA granules. However, S-foci are specific to the post-synaptic compartment. S-foci have been found to contain the repressors SMAUG1 and SMAUG4 as well CaMKIIa, which is known to be a m6A-modified transcript that is critical for synaptic functions. All of these sites of storage can have distinct RNA/protein compositions and can respond to stimuli, except stress granules which respond specifically to cellular stress. YTHDF2 co-localises with both stress granules and P-bodies, with recruitment of modified RNA to P-bodies via YTHDF2 leading to RNA decay. However, YTHDF1/3 only co-localises with stress granules (which have both RNA decay and translation capacity). Importantly, these sites of storage can exchange RNA and protein between themselves and the cytosol such that upon inhibition or promotion of local translation in response to stimulation/stress can occur. This translation of specific transcripts at the synapse is critical for synaptic transmission.

m6A-modified transcripts undergo translation via the actions of YTHDF1, YTHDF3, eIF3 and METTL3. YTHDF1 binds to eIF3 which recruits the small ribosome subunit to mRNA to enhance translation [11, 46]. Another mechanism of m6A-mediated mRNA translation involves direct binding of m6A in the 5’UTR to eIF3. However, m6A modification at the 5’UTR is limited to a small subset of mRNAs, which ensures specificity of translation in response to cellular stress [40]. A third mechanism of m6A-mediated translation involves cytosolic METTL3, which binds to m6A and recruits eIF3 to promote translation in cancer cells [85, 86]. However, the prevalence of this mechanism in other contexts, such as in neurons, is not yet known. This may be due to the fact that METTL3 is predominantly a nuclear protein. Consequently, although m6A can promote translation through multiple mechanisms, the contribution of each of these to local translation in neurons is poorly understood.

One potential mechanism of m6A-mediated control of local translation could be through the activity of m6A erasers. The FTO demethylase is enriched in axons, where its depletion results in decreased local translation of axonal GAP43 mRNA and repressed axon elongation [87]. YTHDF1 also binds to and positively regulates the translation of m6A-modified Robo3.1 mRNA, which encodes an important axon guidance receptor [88]. Furthermore, METTL14 depletion reduces the axonal regeneration of retinal ganglion neurons after injury, a process which involves local translation [89]. Finally, several transcripts which are critical for learning and memory, including CamkIIa, Shank1, and Kif5a, are m6A modified in synaptosomes (containing both pre-synaptic and post-synaptic components), suggesting that the local epitranscriptome may contribute to proteins produced from synaptically localised transcripts [36]. Interestingly, all YTHDF proteins are located at the synapse, and knock-down (KD) of YTHDF1 and YTDHF3 in cultured hippocampal neurons results in altered spine morphology and functional deficits at excitatory synapses [36]. With these findings it seems reasonable that a distinct sub-population of modified RNA are localised to different locations in the neuron, to possibly coordinate a variety of translation-dependent functions.

Active demethylation may occur in response to various environmental cues received by the neuron. If proven to be true, active RNA demethylation would represent a new mechanism within neuronal compartments to ensure that only a specific population of RNA is functionally employed at a given moment in order to tightly coordinate learning and memory processes. Furthermore, as de novo methylation requires new transcription, activity-dependent activation of local demethylating enzymes provides a potential convenient mechanism whereby neurons can rapidly regulate local transcript populations. Recent studies have demonstrated that FTO can demethylate not only m6A but also m6Am in mRNA and small nuclear RNA (snRNA) as well as m1A in transfer RNA (tRNA) [90–92]. Therefore, the effects of FTO depletion could be related to multiple modifications and RNA types, rather than simply m6A and mRNA. Consequently, other demethylases need to be investigated and a demonstration of their function in vitro and in particularly in vivo is required, which will necessitate new advances in the technologies available to study RNA localisation (Box 1).

Box 1: Future Technologies.

Current m6A profiling technologies are extremely limited in their ability to profile m6A in specific neuronal compartments. The fractionation methods used to isolate neuronal compartments yield low quantity and low purity RNA, making enrichment of m6A and subsequent profiling in specific compartments difficult [110]. With techniques such as MeRIP-seq, a large quantity of RNA is required for m6A profiling due to the use of antibodies to enrich for modified RNA. These antibodies can also cross-react with other modifications. Overcoming these input issues therefore requires the use of antibody-independent profiling techniques. For example, DART-seq uses C-to-U deamination adjacent to m6A residues to profile m6A-RNA and only requires 10ng of input RNA [97]. This method holds promise for profiling low quantities of RNA. However, to identify m6A RNA in axons, dendrites and pre/post-synapses after a learning event, DART-seq and other antibody-independent m6A methods must be adopted.

Better ways to isolate axons, dendrites and synapses with little or no contamination are also required. Recently, local translation in excitatory synaptic compartments was investigated using fluorescence activated synaptosome sorting (FASS). In FASS, while synaptosomes are isolated normally using ultracentrifugation, a lipophilic dye (FM4–64) is added which triggers detection of all biological membranes [111], allowing ultrapure synaptosomes (with the pre-synapse and tip of the post-synapse) and reduced neuronal and glial contamination to be isolated [112]. Such a high degree of cell-type specificity and pure compartment isolation, by combining sorting and fractionation methods together, is what is required to confidently determine the specific RNA localised in the brain.

There is also a paucity of techniques available to study RNA reservoir components. While granules and P-bodies have been observed in neurons [77], specific components of transport molecules and storage components have been relatively under-investigated. To achieve a fuller understanding of how polymethylated RNA molecules are segregated into reservoirs after a learning event and which molecules carry out functions immediately after localisation is vital. Doing so will help advance understanding of the differences in RNA molecules and their binding partners that lead to storage or immediate functionalisation in specific brain regions and neuronal compartments.

Finally, although each of these concepts can be studied in vitro using primary neurons, it is more difficult to demonstrate complex localisation mechanisms in vivo. This is because it is difficult to demonstrate RNA transport molecule movement across neuronal compartments after learning in a single animal over time. Instead, multiple animals need to be used, which can introduce variability. Therefore, improved methods are required in order to visualise and study RNA localisation across time in live animals.

Emerging methods to study the localisation and functions of m6A-modified RNA

m6A profiling initially used antibody-based methods [30, 38]. Although significant insight was obtained, precise m6A sites could not be identified. Subsequently, photo-crosslinking-assisted m6A sequencing (PA-m6A-seq) [93] and m6A individual nucleotide-resolution crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (miCLIP) [94] were developed to identify m6A sites at base resolution. However, these approaches still rely on antibody-based detection, and therefore require relatively large quantities of input RNA. Consequently, new antibody-independent methods are being developed. Enzymatic methods include m6A-REF-seq [95] and MAZTER-seq [96] which use a m6A-sensitive RNAse to cleave RNA at ACA motifs. However, because most m6A sites do not occur in such motifs, these methods can only determine a small portion of total m6A targets (16–25%) [96]. In contrast, a promising antibody-independent method, DART-seq (deamination adjacent to RNA modification targets), is capable of identifying a large portion of m6A targets from low amounts of RNA (10ng). This method uses the APOBEC1 cytidine deaminase fused to the m6A-binding YTH domain to induce C-to-U deamination at sites adjacent to m6A residues which can be detected using standard RNA-seq [97]. However, the affinity and specificity of the YTH domain to m6A and the activity of the deaminase enzyme may affect the detection accuracy of the targets [98]. Consequently, instead of using editing enzymes, metabolic labelling has been used to map m6A at base resolution (m6A-label-seq). In m6A-label-seq, RNA is metabolised with modified allyl-SAM or allyl-SeAM cofactors to generate N6-allyladenosine (a6A) at m6A sites. These a6A sites can then be detected using reverse transcription [98]. Furthermore, recently an FTO-assisted selective chemical labelling method called m6A-SEAL has also been developed to profile m6A transcriptome wide in human and plants cells [99].

Though a plethora of m6A profiling techniques exist, these methods have yet to be used to identify specifically localised m6A-modified RNAs in different neuronal compartments after a learning event. This is due to the fact that in order to fully understand the functional role of localised m6A-modified RNA in the brain one must take into account both the temporal and spatial dynamics of RNA. Most studies profile m6A in both pre- and post-synapses [36], but it is possible that these compartments have distinct sub-populations of localised RNA. To address this, a new method called SynTagMA can be used to isolate pre- and post-synaptic compartments. This technique uses the CAMPARI protein (which is calcium dependent and photoinducible) anchored to either synaptophysin to mark axons or PSD95 to mark synapses. Once isolated, axons/synapses can be used to profile m6A in these compartments [100]. Next, two methods to isolate activated synapses, including TimeSTAMP and Synaptic Proximity Ligation Assay (SynPLA) have been developed. With TimeSTAMP, PSD95 is fluorescently labelled in response to stimuli, thereby identifying activated synapses [101]. With SynPLA, PLA is used to detect the synaptic insertion of GluA-containing AMPA receptors, which act as a marker for recently potentiated synapses [102]. Both TimeSTAMP and SynPLA are promising methods that in principle, could be modified to isolate activated synapses from a specific brain region after a learning event and profile m6A-modified RNA in these compartments.

The aforementioned methods focus on profiling m6A-modified RNA in specific neuronal compartments. However, in order to determine the specific roles of these localised m6A-containing RNAs, functional manipulations of a single modified RNA of interest at a given location (instead of region-specific depletion of m6A writers/erasers) is required. The CRISPR-Cas inspired RNA targeting system (CIRTs) delivers specific effector proteins to an RNA of interest. CIRTs can be used to deliver m6A reader proteins to candidate transcripts [103]. When these single transcript manipulations are conducted in KD conditions, the functional roles of m6A-modified localised RNA at the synapse in a learning paradigm can potentially be demonstrated.

To study the temporal of dynamics of localisation, photoactivatable methods can also be applied. For example, mRNA light-activated reversible inactivation by assembled trap (mRNA-LARIAT) optogenetically manipulates the localisation and translation of specific mRNAs by trapping them in clusters. RNA-protein interactions can be visualised, and the effects of clustering on mRNA function in live cells can simultaneously be determined [104].

Finally, the role of m6A in local translation, which is a potential ultimate function of localised RNA also needs to be explored. Initial glimpses of translation processes to quantify newly synthesised proteins using ribosome profiling or stable isotope labelling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) are low-resolution techniques that detect overall changes in protein synthesis [105]. Therefore, fluorescent microscopy techniques have been developed to study local translation in a specific time and space. Fluorescent non-canonical amino acid tagging (FUNCAT) uses azidohomoalanine (AHA), a methionine analogue which can be fluorescently labelled [106]. This analogue incorporates into newly synthesised proteins in methionine-starved conditions and has been used to observe local translation in both pre- and post-synaptic compartments and in axons [106, 107]. Also, in puromycylation assays, instead of using AHA, a low-dose treatment with puromycin is used which incorporates into nascent proteins causing truncation. Using anti-puromycin antibodies, newly synthesised proteins can then be fluorescently labelled [108]. Both FUNCAT and puromycylation assays measure translation status, and these assays can be combined with a proximity ligation assays (PLA) to study specific proteins [105]. FUNCAT-PLA has been used to demonstrate local translation in neurons [109]. While the m6A mark has been shown to be critical for the local translation of GAP-43 in axons [87], the FUNCAT/Puromycin assay has yet to be employed to assess the translation kinetics of m6A modified transcripts in a specific neuronal compartment.

The aforementioned methods represent significant advances in technologies in comparison to the early techniques originally used to demonstrate RNA localisation in the brain. However, further progress must be made if the complexity of localisation and local translation is to be fully understood. New photoinducible methods will need to be designed in order to identify localised and modified RNA in a given brain region and within specific neuronal compartments. Furthermore, although these methods can be used in vitro, the major obstacles in studying RNA localisation, RNA-protein interactions and associated functions in vivo will remain until higher resolution approaches for use in the brain are developed.

Concluding Remarks

In summary, RNA localisation and local translation enhance the capacity of neurons to respond rapidly to stimuli, and these processes can potentially be fine-tuned by dynamic and reversible mechanisms such as RNA modification. m6A is particularly enriched in the brain and is thought to play a significant role in RNA localisation to axons, dendritic compartments and activated synapses, and possibly in the coordinated regulation of RNA reservoirs. To achieve a deeper mechanistic understanding of how RNA is localised and subsequently regulated in specific compartments, the spatial and temporal dynamics of specific modified RNAs must be further explored.

Outstanding Questions.

Are mRNAs transported and regulated as single molecules or assembled into multimolecular transport units? While a specific mRNA is capable of binding only a subset of RBPs, a single RBP, with multiple RNA binding domains is capable of binding multiple transcripts. Thus, are transcripts bound by the same RBP transported together? If so, what is the composition of these transport units after a learning event? Is the composition of transport units dictated by the RBP, the transcript sequence or structure (including m6A distribution along the transcript), the ultimate function of the RNA molecule or final location of the transcript?

It is possible that multiple different RNA modifications occur along a single transcript, thus multiple RBPs could bind to a single RNA molecule. With over 170 RNA modifications and only a fraction of these being profiled in the brain, it seems highly likely that many more modifications in combination with m6A contribute to the specificity of RNA localization processes to various neuronal compartments. However, first, how can one determine the various modifications on a single transcript? Given the many modifications, which RBPs bind after a learning event in a specific neuronal compartment? Then, which modification-protein combination dictates the function of the RNA molecule at a specific location? Does the same modification-protein combination dictate a different function in a different neuronal compartment? If so, how are these differences in functions regulated? What additional factors (such as non-coding RNAs) contribute to the localization and function of modified RNA molecules?

What are the biological functions of particular m6A modified RNA molecules in vivo? How can one begin to study RNA-RBP dynamics in vivo in animal models? Is it possible to study these dynamics over time in a single animal?

Highlights.

Epitranscriptomics or “RNA modifications” contribute to RNA localization processes in the brain

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is an RNA modification potentially critical for localization of RNA

m6A not only has roles in nuclear processing and export of RNA molecules but also likely contributes to phase separation of RNA-protein complexes into RNA reservoirs (such as RNA granules, stress granules and P-bodies) and local translation at specific neuronal compartments.

Many new techniques are capable of profiling m6A modified transcripts at single base resolution. However, these techniques need to be adapted to determine transcripts localized to various locations of the neuron including activated synapses, axons and dendritic compartments.

Investigations into the roles of m6A in RNA biology is rapidly expanding but requires new techniques to fully understand m6A’s role in RNA localization in the brain.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge grant support from the NHMRC (GNT1181359-TWB), the NIH (R01MH118366 and DP1DA046584-KM) and AMED (18dm0307023h0001-DOW) and Xingliao Talents Program (XLYC1802007-DOW). SUM is supported by the University of Queensland and is a recipient of a Westpac Future Leaders Scholarship. The authors thank Ms. Rowan Tweedale for editing of the manuscript and Dr. Nick Valmas for figure graphics.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sanchez-Carbente Mdel R and Desgroseillers L (2008) Understanding the importance of mRNA transport in memory. Prog Brain Res 169, 41–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuditta A and Brzin M (1968) Protein synthesis in the isolated giant axon of the squid. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 59, 1284–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steward O and Levy WB (1982) Preferential localization of polyribosomes under the base of dendritic spines in granule cells of the dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci 2, 284–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garner CC, et al. (1988) Selective localization of messenger RNA for cytoskeletal protein MAP2 in dendrites. Nature 336, 674–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burgin K, et al. (1990) In situ hybridization histochemistry of Ca super(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in developing rat brain. J. Neurosci 10, 1788–1798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyejin Kang EMS (1996) A Requirement for Local Protein Synthesis in Neurotrophin-Induced Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity. Science 273, 1402–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steward O, et al. (1998) Synaptic activation causes the mRNA for the IEG Arc to localize selectively near activated postsynaptic sites on dendrites. Neuron 21, 741–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D, et al. (2009) Synapse- and stimulus-specific local translation during long-term neuronal plasticity. Science 324, 1536–1540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boccaletto P, et al. (2018) MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acid Res. 46, D303–D307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Widagdo J, et al. (2016) Experience-dependent accumulation of N6-methyladenosine in the prefrontal cortex is associated with memory processes in mice. J. Neurosci 36, 6771–6777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi H, et al. (2018) m6A facilitates hippocampus-dependent learning and memory through YTHDF1. Nature 563, 249–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Z, et al. (2018) METTL3-mediated N6-methyladenosine mRNA modification enhances long-term memory consolidation. Cell Res. 28, 1050–1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walters BJ, et al. (2017) The role of The RNA demethylase FTO (fat mass and obesity-associated) and mRNA methylation in hippocampal memory formation. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 1502–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koranda J, et al. (2018) Mettl14 is essential for epitranscriptomic regulation of striatal function and learning. Neuron 99, 283–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buxbaum AR, et al. (2015) Single-molecule insights into mRNA dynamics in neurons. Trends in Cell Biol. 25, 468–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel KL, et al. (2020) Mechanisms and consequences of subcellular RNA localization across diverse cell types Traffic, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiebler M and Bassell G (2006) Neuronal RNA granules: movers and makers. Neuron 51, 685–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rook MS, et al. (2000) CaMKIIalpha 3’ untranslated region-directed mRNA translocation in living neurons: visualization by GFP linkage. J. Neurosci 20, 6385–6395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikl M, et al. (2011) Independent localization of MAP2, CaMKIIα and β-actin RNAs in low copy numbers. EMBO Rep. 12, 1077–1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazal FM, et al. (2019) Atlas of Subcellular RNA Localization Revealed by APEX-Seq. Cell 178, 473–490 e426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang P, et al. (2019) Mapping spatial transcriptome with light-activated proximity-dependent RNA labeling. Nat Chem Biol 15, 1110–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bokar JA (2005) The biosynthesis and functional roles of methylated nucleosides in eukaryotic mRNA. Fine-tuning of RNA functions by modification and editing. Springer, 141–177 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jia G, et al. (2011) N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol 7, 885–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao BS, et al. (2017) Post-transcriptional gene regulation by mRNA modifications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 18, 31–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaccara S, et al. (2019) Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 20, 608–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wickramasinghe V and Laskey RA (2015) Control of mammalian gene expression by selective mRNA export. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 16, 431–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ke S, et al. (2017) m(6)A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Gen. & Dev 31, 990–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gokhale N, et al. (2016) N6-methyladenosine in flaviviridae viral RNA genomes regulates infection. Cell Host & Micr. 20, 654–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lichinchi G, et al. (2016) Dynamics of the human and viral m(6)A RNA methylomes during HIV-1 infection of T cells. Nat. Micro 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer K, et al. (2012) Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3’UTRs and near stop codons. Cell 149, 1635–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hess ME, et al. (2013) The fat mass and obesity associated gene (Fto) regulates activity of the dopaminergic midbrain circuitry. Nat. Neurosci 16, 1042–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X, et al. (2019) Down-Regulation of m6A mRNA methylation Is involved in dopaminergic neuronal death. ACS Chem. Neurosci 10, 2355–2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoon K, et al. (2017) Temporal control of mammalian cortical neurogenesis by m6A methylation. Cell 171, 877–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edens BM, et al. (2019) FMRP modulates neural differentiation through m6A-dependent mRNA nuclear export. Cell Reports 28, 845–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Engel M, et al. (2018) The role of m6A/m-RNA methylation in stress response regulation. Neuron 99, 389–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Merkurjev D, et al. (2018) Synaptic N6-methyladenosine (m6A) epitranscriptome reveals functional partitioning of localized transcripts. Nat. Neuro 21, 1004–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edupuganti R, et al. (2017) N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) recruits and repels proteins to regulate mRNA homeostasis. Nat. Struct Mol. Biol 24, 870–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominissini D, et al. (2012) Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 485, 201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ke S, et al. (2015) A majority of m(6)A residues are in the last exons, allowing the potential for 3’ UTR regulation. Gen. & Dev 29, 2037–2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyer K, et al. (2015) 5′ UTR m6A promotes cap-independent translation. Cell 163, 999–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi J, et al. (2016) N6-methyladenosine in mRNA disrupts tRNA selection and translation-elongation dynamics. Nat. Struct Mol. Biol 23, 110–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Slobodin B, et al. (2017) Transcription impacts the efficiency of mRNA translation via co-transcriptional N6-adenosine methylation. Cell 169, 326–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mao Y, et al. (2019) m6A in mRNA coding regions promotes translation via the RNA helicase-containing YTHDC2. Nat. Comm 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roundtree I, et al. (2017) YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N6-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xiao W, et al. (2016) Nuclear m(6)A reader YTHDC1 regulates mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 61, 507–519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang X, et al. (2015) N6-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell 161, 1388–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu Y and Zhuang X (2020) m6A-binding YTHDF proteins promote stress granule formation. Nat. Chem. Biol [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, et al. (2014) N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 505, 117–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li A, et al. (2017) Cytoplasmic m6A reader YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation. Cell Res. 2017, 444–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shi H, et al. (2017) YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N6-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 27, 315–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zaccara S and Jaffrey S (2020) A Unified Model for the Function of YTHDF Proteins in Regulating m6A-Modified mRNA. Cell 181, 1–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.N. L, et al. (2015) N(6)-methyladenosine-dependent RNA structural switches regulate RNA-protein interactions. Nature 518, 560–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu N, et al. (2017) N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Research 45, 6051–6063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alarcón C, et al. (2015) N6-methyladenosine marks primary microRNAs for processing. Nature 519, 482–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alarcón C, et al. (2015) HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m6A-dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell 192, 1299–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sudhakaran I and Ramaswami M (2017) Long-term memory consolidation: The role of RNA-binding proteins with prion-like domains. RNA Biol: RNA in dis. & dev 14, 568–586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu L, et al. (1998) CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation and the regulation of experience-dependent translation of alpha-CaMKII mRNA at synapses. Neuron 21, 1129–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ries R, et al. (2019) m6A enhances the phase separation potential of mRNA. Nature 571, 424–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anders M, et al. (2018) Dynamic m6A methylation facilitates mRNA triaging to stress granules. Life Sci. Alliance 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harrison A and Shorter J (2017) RNA-binding proteins with prion-like domains in health and disease. The Bioc. Journ 474, 1417–1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Holt CE and Bullock SI (2009) Subcellular mRNA localization in animal cells and why it matters. Science 326, 1212–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang H, et al. (2002) Dendritic BC1 RNA: functional role in regulation of translation initiation. J. Neurosci 22, 10232–10241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schratt GM, et al. (2006) A brain-specific microRNA regulates dendritic spine development. Nature 439, 283–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yedavalli V, et al. (2004) Requirement of DDX3 DEAD Box RNA helicase for HIV-1 Rev-RRE export function. Cell 119, 381–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chahar H, et al. (2013) P-body components LSM1, GW182, DDX3, DDX6 and XRN1 are recruited to WNV replication sites and positively regulate viral replication. Virology 436, 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanai Y, et al. (2004) Kinesin transports RNA: Isolation and characterization of an RNA-transporting granule. Neuron 43, 513–525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fritzsche R, et al. (2013) Interactome of two diverse RNA granules links mRNA localization to translational repression in neurons. Cell Rep 5, 1749–1762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Calviello L, et al. (2019) DDX3 depletion selectively represses translation of structured mRNAs. bioRxiv [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen H, et al. (2016) DDX3 modulates neurite development via translationally activating an RNA regulon involved in Rac1 activation. J. Neurosci 36, 9792–9804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shah A, et al. (2017) The DEAD-Box RNA helicase DDX3 interacts with m6A RNA demethylase ALKBH5. Stem Cells Intern. 2017, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomas M, et al. (2011) RNA granules: the good, the bad and the ugly. Cell. Sig 23, 324–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mateju D, et al. (2020) Single-molecule imaging reveals translation of mRNAs localized to stress granules. bioRxiv [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steward O, et al. (2015) Localization and local translation of Arc/Arg3.1 mRNA at synapses: some observations and paradoxes. Fron. in Mol. Neurosci 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kulkarni M, et al. (2010) On track with P-bodies Bioc. Soc. Trans 38, 242–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brengues M, et al. (2005) Movement of eukaryotic mRNAs between polysomes and cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science 310, 486–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baez M, et al. (2011) Smaug1 mRNA-silencing foci respond to NMDA and modulate synapse formation. The Journ. of Cell Biol 195, 1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bakthavachalu B, et al. (2018) RNP-granule assembly via ataxin-2 disordered domains is required for long-term memory and neurodegeneration. Neuron 98, 754–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Graber T, et al. (2013) Reactivation of stalled polyribosomes in synaptic plasticity. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 16205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu S, et al. (2020) m6A facilitates YTHDF-independent phase separation. Journ. of Cell. & Mol. Med 24, 2070–2072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gao Y, et al. (2019) Multivalent m6A motifs promote phase separation of YTHDF proteins. Cell Res. 29, 767–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang H, et al. (1999) Neurotrophin regulation of beta-actin mRNA and protein localization within growth cones. J. Cell Biol 147, 59–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Link W, et al. (1995) Somatodendritic expression of an immediate early gene is regulated by synaptic activity. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5734–5738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tongiorgi E, et al. (1997) Activity-dependent dendritic targeting of BDNF and TrkB mRNAs in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci 17, 9492–9505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brigidi S, et al. (2019) Genomic decoding of neuronal depolarization by stimulus-specific NPAS4 heterodimers. Cell 179, 373–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 85.Lin S, et al. (2016) The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes translation in human cancer cells. Mol. Cell 62, 335–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Choe J, et al. (2018) mRNA circularization by METTL3-eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature 561, 556–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yu J, et al. (2018) Dynamic m6A modification regulates local translation of mRNA in axons. Nucleic Acic Res. 46, 1412–1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhuang M, et al. (2019) The m6A reader YTHDF1 regulates axon guidance through translational control of Robo3.1 expression. Nucleic Acid Res. 47, 4765–4777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Weng Y, et al. (2018) Epitranscriptomic m6A regulation of axon regeneration in the adult mammalian nervous system. Neuron 97, 313–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhang X, et al. (2019) Structural insights into FTO’s catalytic mechanism for the demethylation of multiple RNA substrates. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 2919–2924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mauer J, et al. (2019) FTO controls reversible m6Am RNA methylation during snRNA biogenesis. Nat. Chem. Biol 15, 340–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wei J, et al. (2018) Differential m6A, m6Am, and m1A demethylation mediated by FTO in the cell nucleus and cytoplasm. Mol. Cell 71, 973–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen K, et al. (2015) High‐resolution N6‐Methyladenosine (m6A) map using photo-crosslinking‐assisted m6A sequencing. Ang. Chem. Intern. Ed 54, 1587–1590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Linder B, et al. (2015) Single-nucleotide-resolution mapping of m6A and m6Am throughout the transcriptome. Nat. Methods 12, 767–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang Z, et al. (2019) Single-base mapping of m6A by an antibody-independent method Sci. Advan 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Garcia-Campos M, et al. (2019) Deciphering the “m6A Code” via antibody-independent quantitative profiling. Cell 178, 731–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Meyer K (2019) DART-seq: an antibody-free method for global m6A detection. Nat. Methods 16, 1275–1280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shu X, et al. (2020) A metabolic labeling method detects mA transcriptome-wide at single base resolution. Nat. Chem. Biol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang Y, et al. (2020) Antibody-free enzyme-assisted chemical approach for detection of N6-methyladenosine. Nat. Chem. Biol 16, 896–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Perez-Alvarez A, et al. (2019) Freeze-frame imaging of synaptic activity using SynTagMA Nat. Comm 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Butko MT, et al. (2012) Fluorescent and photo-oxidizing TimeSTAMP tags track protein fates in light and electron microscopy. Nat. Neuro 12, 1742–1751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Dore K, et al. (2020) SYNPLA, a method to identify synapses displaying plasticity after learning. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 3214–3219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rauch S, et al. (2019) Programmable RNA-guided RNA effector proteins built from human parts. Cell 178, 122–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kim NY, et al. (2020) Optogenetic control of mRNA localization and translation in live cells. Nat. Cell Biol 22, 341–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Biswas J, et al. (2019) Fluorescence Imaging Methods to Investigate Translation in Single Cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dieterich DC, et al. (2010) In situ visualization and dynamics of newly synthesized proteins in rat hippocampal neurons. Nat Neurosci 13, 897–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kos A, et al. (2016) Monitoring mRNA Translation in Neuronal Processes Using Fluorescent Non-Canonical Amino Acid Tagging. Journ. of Histo. & Cytochem 64, 323–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Starck S, et al. (2004) A general approach to detect protein expression in vivo using fluorescent puromycin conjugates. Chem. & Biol 11, 999–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dieck ST, et al. (2015) Direct visualization of identified and newly synthesized proteins in situ. Nat Neurosci 12, 411(417) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nainar S, et al. (2016) Evolving insights into RNA modifications and their functional diversity in the brain. Nat. Neuro 19, 1292–1298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hafner A, et al. (2019) Local protein synthesis is a ubiquitous feature of neuronal pre- and postsynaptic compartments. Science 364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Luquet E, et al. (2017) Purification of synaptosome populations using fluorescence-activated synaptosome sorting In Synapse Development: Methods and Protocols (Poulopoulos A, ed), pp. 121–134, Springer; New York: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chang MQ, et al. (2017) Region-specific RNA m6A methylation represents a new layer of control in the gene regulatory network in the mouse brain. Open Biol. 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang Y, et al. (2018) N6-methyladenosine RNA modification regulates embryonic neural stem cell self-renewal through histone modification. Nat. Neuro. 21, 195–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wang C, et al. (2018) METTL3-mediated m6A modification is required for cerebellar development. PLoS Biol. 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ma C, et al. (2018) RNA m6A methylation participates in regulation of postnatal development of the mouse cerebellum. Gen. Biol 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Li L, et al. (2017) Fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) protein regulates adult neurogenesis. Hum. Mol. Gen 26, 2398–2411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bai L, et al. (2018) m6A demethylase FTO regulates dopaminergic neurotransmission deficits caused by arsenite. Tox. Sci 165, 431–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wu R, et al. (2019) A novel m6A reader Prrc2a controls oligodendroglial specification and myelination. Cell Res. 29, 23–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]