Abstract

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) plays an essential role in eliminating oxidative damage of lactic acid bacteria. Streptococcus thermophilus, an important probiotic lactic acid bacterium, often inevitably suffers from various oxidative stress during dairy fermentation. In this study, to confer high-level oxidative resistance, the sod gene from Lactobacillus casei was heterologous expressed in S. thermophilus S-3 using our previous constructed native constitutive promoter library. The enzyme activity of SOD was significantly enhanced in engineered S. thermophilus by promoter #14 (2070 U/mg). Furthermore, the strategy of multi-copy sod-expressing cassettes was employed to improve SOD activity. The maximum activity (2750 U/mg) was obtained by the two-copy sod recombinant, which was 1.5-fold higher than that of one-copy recombinant. In addition, the survival rate of multi-copy sod recombinants was increased about 97-fold with 3.5 mmol/L H2O2 treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report of multi-copy sod gene expression in S. thermophilus, which exerts a positive effect on coping with oxidative stress to enhance the potential of industrial application.

Keywords: Streptococcus thermophilus, superoxide dismutase, native constitutive promoter, multicopy gene expression, oxidative stress

Introduction

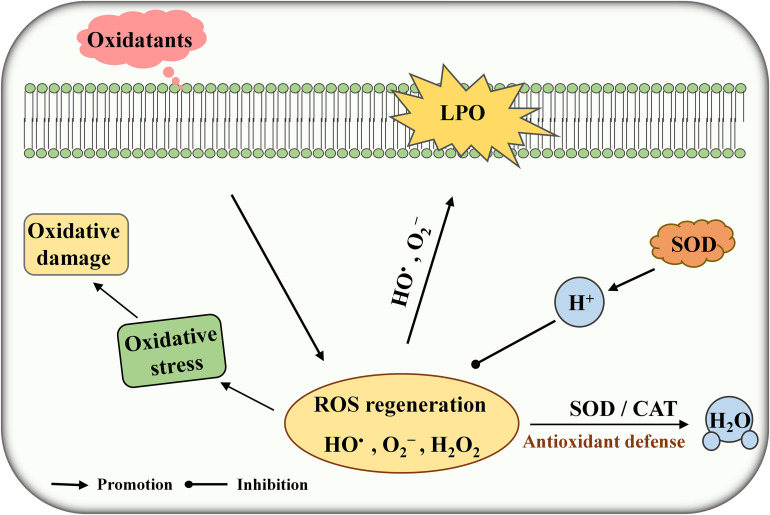

Under normal physiological conditions, cells can generate a massive amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during metabolism in the presence of oxygen. ROS including superoxide (O2–), hydroxyl radical (HO•), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) may cause lipid peroxidation, cell membrane damage, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases (Li et al., 2019). Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is one of the major antioxidant enzymes responsible for protecting the cells against the harmful effects of ROS (Figure 1). SODs are usually grouped on the basis of metal content such as CuSOD, MnSOD, and FeSOD. FeSOD and MnSOD are belonging to a homologous group and playing an important role in the living organism (Russo Krauss et al., 2015). Some lactic acid bacteria (LAB) possess cambialistic SOD, which can bind and exchange Fe or Mn in the active site and show substantial but different activity (De Vendittis et al., 2010). Streptococcus thermophilus AO54 and LMG 18311 contain a single MnSOD which are not sensitive to H2O2 treatment in the presence of high Mn concentration (Andrus et al., 2003; De Vendittis et al., 2012). Serata et al. (2018) found a correlation between SOD activity and Mn concentration in Lactobacillus casei Shirota. Thus, enhancing SOD expression is an efficient method to reduce oxidative stress in living cells. For example, heterologous expression of SOD can significantly improve the tolerance toward H2O2 stress in LAB such as Bifidobacterium longum, L. casei, and L. rhamnosus (An et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2016).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic diagram of superoxide dismutase (SOD) against (reactive oxygen species) ROS toxicity. LPO, lipid peroxidation.

S. thermophilus is one of the homofermentative LAB commonly used in food fermentation including yogurt and cheese, which helps food safety, taste, and quality (Sorensen et al., 2016). Furthermore, it has latent beneficial effects on human health, such as promoting lactose digestion, modulating gut microbiota, alleviating intestinal disorder, and lowering blood pressure and cholesterol (Zhai et al., 2020). S. thermophilus is inevitably exposed to various environmental pressures during food production and beverage consumption. Accordingly, tolerance to oxidative stress is critical for the survival of S. thermophilus. So far, there are limited studies on SOD expression for improving antioxidant activity in S. thermophilus.

S. thermophilus S-3 was isolated from traditional dairy products by our laboratory. It can utilize galactose, which is an ideal property of LAB (Xiong et al., 2019a). Exopolysaccharide produced by S-3 effectively improves the viscosity and taste of yogurt (Xu et al., 2018). In our previous study, a set of constitutive promoters with different strengths was mined by the analysis of RNA and genome sequencing in S-3 (Kong et al., 2019; Xiong et al., 2019b). In this study, a native constitutive promoter library and multi-copy strategy were used to improve enzyme activity of SOD and the survival under H2O2 stress in S-3. Our results provide protection strategy for S. thermophilus or other LAB from oxidative damage.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Condition

Bacteria and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli Top10 was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. S. thermophilus S-3 was cultured in M17 medium supplemented with 2% lactose (LM17) at 37°C. When required, erythromycin (10 μg/mL for S. thermophilus) and kanamycin (50 μg/mL for E. coli) were added.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this work.

| Strains | Description | Sources |

| E. coli Top10 | Host for cloning | Our lab |

| S. thermophilus S-3 | Wild type | Our lab |

| L. casei LC2W | The source of SOD | Our lab |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKLH32 | pIB184 derived, carrying Kanr from pnCL03 | Our lab |

| pKLH295 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #1 promoter | This study |

| pKLH296 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #2 promoter | This study |

| pKLH297 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #3 promoter | This study |

| pKLH298 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #4 promoter | This study |

| pKLH299 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #5 promoter | This study |

| pKLH300 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #6 promoter | This study |

| pKLH301 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #7 promoter | This study |

| pKLH302 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #8 promoter | This study |

| pKLH303 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #10 promoter | This study |

| pKLH304 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #15 promoter | This study |

| pKLH305 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #16 promoter | This study |

| pKLH306 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #17 promoter | This study |

| pKLH161 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #9 promoter | Kong et al., 2019 |

| pKLH162 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #11 promoter | Kong et al., 2019 |

| pKLH163 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #12 promoter | Kong et al., 2019 |

| pKLH164 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #13promoter | Kong et al., 2019 |

| pKLH165 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #14 promoter | Kong et al., 2019 |

| pKLH167 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the #18 promoter | Kong et al., 2019 |

| pKLH168 | pKLH32 derived, for overexpression of sod under the P32 promoter | Kong et al., 2019 |

| pKLH337 | Derived from pKLH167, for overexpression of sod. | This study |

| pKLH341 | Derived from pKLH337, for overexpression of sod. | This study |

| pKLH344 | pKLH341 digested by SacI, for overexpression of sod. | This study |

Plasmid Construction

All primers used in this study are listed in Table 2. All molecular manipulations were carried out using standard cloning techniques (Kong et al., 2019). The DNA fragment of SOD was amplified from L. casei by PCR using a pair of primer SOD_LC2W-F71/SOD_LC2W-R97 and inserted into pKLH71 and pKLH81 (digestion by BamHI and BglII) to obtain pKLH295 and pKLH303, respectively, by the ClonExpress MultiS one-step cloning kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). As the above method, the gene of sod was cloned into pKLH73-pKLH79 and pKLH86-pKLH88 containing different promoters by digestion of BamHI and EcoRI (Kong et al., 2019), yielding the plasmids pKLH296-pKLH302 and pKLH304-pKLH306. Promoters name and sequence are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study.

| Primers | Sequences (5′-3′) |

| SOD_LC2W-F71 | aaggagagtattgtaggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F73 | tagggggatacagaaggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F74 | ggaggcttttcctaaggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F75 | taggagatccaaactggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F76 | aggagaattttgcaaggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F77 | aaaggggaagacattggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F78 | taaggagaatacggtggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F79 | tatgatatcgagatgggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F81 | gaagacattattttcggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F86 | aggaggaaatcactaggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F87 | aaggagatagaacatggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-F88 | cgtgtccatgcagagggatccATGACATTTGTTTTGCCAGATTTACC |

| SOD_LC2W-R97 | cttaagcttatcgatagatctTCAGGCGTTTGTATCGGGATG |

| SOD_LC2W-R | agatctcgagctctagaattcTCAGGCGTTTGTATCGGGATG |

| pKLH167-ske-F | gaattctagagctcgagatctatcg |

| pKLH167-ske-R | tcaggcgtttgtatcggg |

| ske1717-SOD-F | atcccgatacaaacgcctgaAAAGATATTTAAAAAGAGTGAGTACTGGG |

| ske1717-SOD-R | gatctcgagctctagaattcTCAGGCGTTTGTATCGGG |

| ske1717-SOD-R1 | cattctttgactaatcactttcaggcgtttgtatcggg |

| ske1717-SOD-F1 | cgagatctatcgataagcttaaagatatttaaaaagagtgagtactggg |

| pKLH337-ske-R | aagcttatcgatagatctcgagctct |

| pKLH337-ske-F | aagtgattagtcaaagaatggtgatgacaattg |

| pKLH314-SOD-F | gatacaaacgcctgagagctcAAAGATATTTAAAAAGAGTGAGTACTGGG |

| pKLH314-SOD-R | ttatcgatagatctcgagctcTCAGGCGTTTGTATCGGGAT |

| SOD-real-F | TGAACCTTACATTGACGCAACAACG |

| SOD-real-R | AGTTGCTCAATGGATTTGCCGG |

Promoter #14 and SOD (pKLH167-ske-F/ske1717-SOD-R) were amplified from pKLH167 and ligated into the backbone of pKLH167 using a pair of primer pKLH167-ske-F/pKLH167-ske-R, yielding pKLH337. Then, promoter #14 and SOD were amplified from pKLH167 and ligated into the backbone of pKLH337, yielding pKLH341. Finally, the promoter #14 and SOD were digested by SacI and inserted into plasmid pKLH341 to create pKLH344.

RNA Preparations and Real-Time Quantitative PCR Analysis

The cells of S. thermophilus recombinants were collected at 24 h and total RNA was extracted with a Trizol kit (Takara). The quantification and integrity of RNA were determined by Nanodrop2000. The cDNA prepared with PrimeScriptRT reagent kit (Takara) was used as a template for RT-qPCR. RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara). The primers of RT-qPCR are listed in Table 2. The data of each gene was analyzed using 2–△△CT method with recA as a reference gene (Xiong et al., 2019b). Three independent biological replicates were performed for RT-qPCR experiment.

Detection of SOD Activity in S. thermophilus Recombinants

The sod plasmids pKLH161-pKLH165, pKLH167-pKLH168, and pKLH295-pKLH306 as well as the control plasmid pKLH32 (without sod) were transformed into S-3 by electroporation. S. thermophilus transformants were harvested at 24 h. The transformants were cultivated for 24 h at 37°C and harvested by centrifugation at 8000 × g for 2 min at 4°C. The samples were suspended in PBS (pH 7.0) for ultrasonic pretreatment (BRANSON S-450D, United States; pulse on 4 s, pulse off 6 s, total time 40 min), and cell debris were removed by centrifugation (12000 × g, 2 min, 4°C). The supernatants were collected as enzyme solution. SOD activity was determined using a WST-1 SOD assay kit (Nanjing Jian Cheng Co., China) according to manufacturer recommendation. A mixture of 200 μL substrate application solution, 20 μL of enzyme working fluid, and 20 μL of enzyme solution was incubated at 37°C for 20 min, and measured using spectrophotometry at 450 nm. The concentration of total protein was determined by modified Bradford reagent (Sangon Biotech, China) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. One unit (U/mg) of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme per mg of total protein corresponding to the SOD inhibition rate reaching 50% in the reaction system (Kong et al., 2019).

Growth of S. thermophilus Under Oxidative Stress Conditions

The multi-copy sod recombinants were cultured in LM17 medium containing erythromycin at 37°C for 12 h. Then the seeds were inoculated (3% v/v) into fresh LM17 medium broth supplemented with H2O2 (1 and 2.5 mmol/L) to determine their growth under aerobic conditions, respectively. Furthermore, colony-forming units per milliliter (CFU/mL) was obtained by taking 10 μL stationary phase cultures (10-fold serial dilutions) on LM17 plate containing H2O2 (3.5 mmol/L) at 37°C for 48 h (anaerobic conditions), respectively.

Results and Discussion

Heterologous Expression of SOD Using Native Constitutive Promoter Library in S. thermophilus

The food-grade S. thermophilus is a facultative anaerobic bacterium and often exposed to oxygen stress during the fermentation of yogurt or meat products. SOD has demonstrated to protect LAB from oxidative stress (Chang and Hassan, 1997; Zhai et al., 2020). Expression of the sod from L. casei (sod-lc) has significantly increased the activity of SOD and superoxide radical scavenging activity in E. coli (Liu et al., 2011). Additionally, the functional gene from L. casei could be more suitable for heterologous expression in S. thermophilus because L. casei and S. thermophilus are belonging to the group of LAB. Thus, to enhance SOD activity in S-3, we selected sod-lc for heterologous expression using our previous constructed native constitutive promoter library (Kong et al., 2019). The strength of 18 promoters including 7 strong promoters (#6, #9, #11, #12, #13, #14, and #18) and 11 weak promoters (#1–#5, #10, and #15–#17) were detected in Supplementary Table 1.

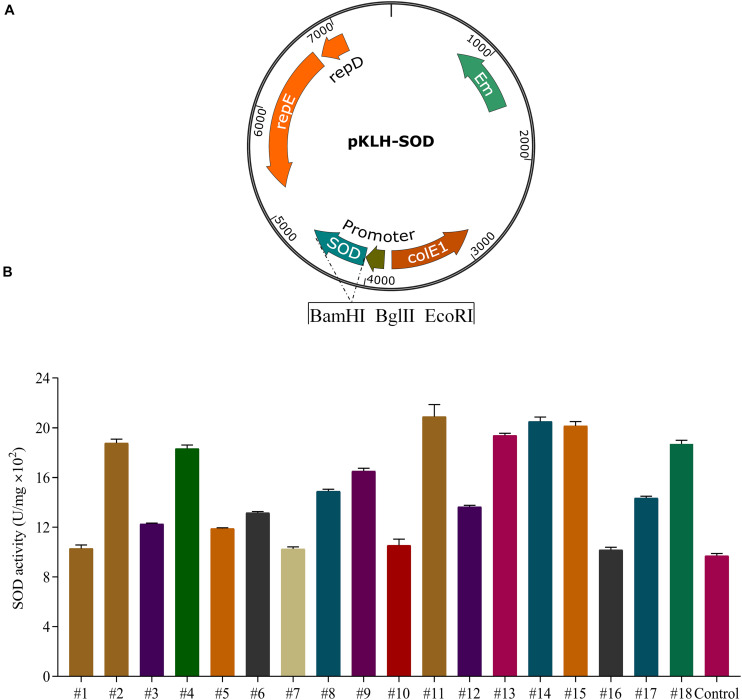

For the recombinants of S. thermophilus (Figure 2A), the activities of SOD were increased 1.1–2.2 folds compared with the control strain S-3/pKLH32 (empty plasmid) under constitutive promoters with different strength (Figure 2B). Strong promoters (#11 and #14) markedly increased 2.2-fold of SOD activity compared with that of the control. The highest enzyme activity of SOD was 2070 U/mg. Interestingly, overexpression of sod by weak promoters (#2, #4, and #15) also significantly enhanced 1.95, 1.93, and 2.12 folds of enzymatic activity. It might be attributed that the ribosomal binding sites of these promoters are more suitable for SOD expression. These results showed that 8 recombinant strains using promoters #2, #4, #9, #11, #13, #14, #15, and #18 were superior to the currently reported highest SOD activity (1500 U/mg) of S. thermophilus CRL807 (Del Carmen et al., 2014). Our previous study found a higher activity of SOD by promoter #14 in comparison with promoter #11 in S. thermophilus and L. casei (Kong et al., 2019). Therefore, we selected promoter #14 for further fine-tuning sod expression.

FIGURE 2.

Expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in S. thermophilus S-3. Schematic representation of recombinant expression vectors containing sod gene from L. casei LC2W (A). Application of a native constitutive promoter library from S. thermophilus for the expression of SOD (B). SOD expression by the selected 18 promoters in S-3, using wild type with empty plasmid as control. The error bars indicate the standard deviations from three independent replicates.

Effect of Multi-Copy sod-Expression Cassettes in S. thermophilus

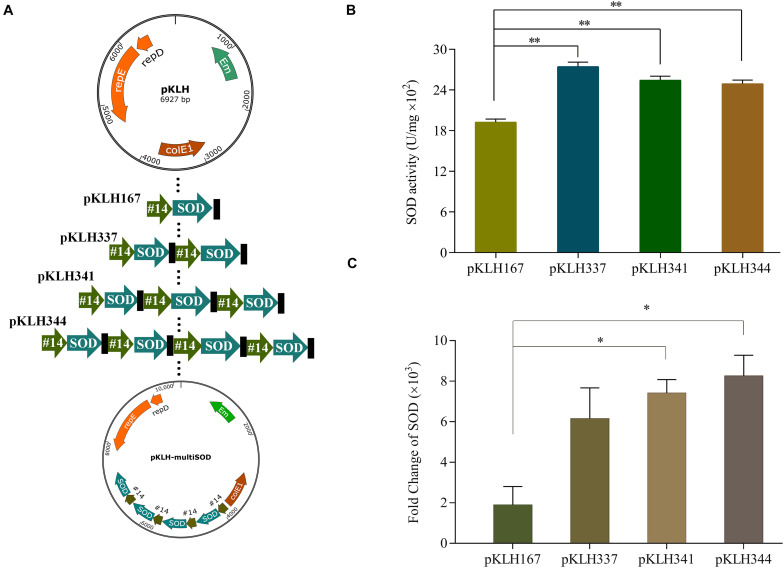

Multi-copy expression cassette is an important strategy to significantly enhance the expression of recombinant proteins (Zhu et al., 2009). Wang et al. (2014) applied this strategy to achieve the maximum yield at the three copies of BmK1 gene, which improved 2.09-fold compared with the control. However, an optimal gene copy number should be considered because of metabolic burden by protein overexpression (Rawsthorne et al., 2006). In some cases, it results in reducing the expression of protein by further increasing gene copy number. Here, multi-copy expression cassette was used to further enhance the expression of SOD. One to four copies of sod-lc gene expression were constructed under promoter #14 (Figure 3A), which one to four copy number recombinants named as S-3/pKLH167, S-3/pKLH337, S-3/pKLH341, and S-3/pKLH344. The maximum activity of SOD was obtained by S-3/pKLH337 (2750 U/mg), which improved 1.45-fold compared with that of S-3/pKLH167 (Figure 3B). SOD activity of S-3/pKLH337 was ∼1.8-fold higher than that (1500 U/mg) of S. thermophilus CRL807 (Del Carmen et al., 2014). SOD activities of S-3/pKLH341 and S-3/pKLH344 were also significantly increased 1.34 and 1.32 folds, respectively. Due to metabolic burden caused by protein overexpression, SOD expression does not increase indefinitely with an increase in copy number. Shu et al. (2016) had a similar result that two copies of expression cassette achieved the highest activity of serine protease, not the four copies. It suggested that the multi-copy strategy is efficient for the expression of SOD and other functional proteins.

FIGURE 3.

Expression of multi-copy sod in S. thermophilus S-3. Construction of vectors with increasing copy of the sod expression cassette (A). Analysis of the enzyme activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in recombinants (B). Analysis of the transcriptional level by RT-qPCR in recombinants (C). The error bars show the standard deviations from three independent replicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Due to the highest expression of SOD in two copies recombinant, the relationship between gene copy number and transcription change were evaluated by RT-qPCR. The expression of sod in all multi-copy recombinants were remarkably increased >2000-fold at the transcriptional level compared with the empty plasmid strain (Figure 3C). Gene expression of sod were increased 3.9, 5.2, and 5.9-fold in multi-copy recombinants S-3/pKLH337, S-3/pKLH341, and S-3/pKLH344 compared to one copy S-3/pKLH167. It indicated that gene copy number has strongly correlated with the level of sod expression, not SOD activity. Our result was similar to the report by Shu et al. (2016) that higher gene copy number increased gene expression but not protein expression level.

Some bacteria possess cambialistic SOD capable of function with Fe or Mn in the active site (De Vendittis et al., 2010). The metal cofactor Mn and Fe are critical for SOD activity (Russo Krauss et al., 2015). To assess the effect of metal ions on SOD activity, we added 1 mmol/L Fe or Mn in the culture medium of S. thermophilus recombinants. The addition of Mn increased SOD activity of S-3/pKLH337 by 1.7-fold, up to 4723 U/mg (Table 3). In particular, SOD activity of S-3/pKLH337 was also 4.7-fold higher than that of control strain (S-3/pKLH32). However, addition of Fe resulted in 31% and 22% decrease of SOD activity in S-3/pKLH32 and S-3/pKLH337, respectively. It is consistent with the result by Chang and Hassan (1997) that Fe inhibits enzymatic activity of SOD. Russo Krauss et al. (2015) showed that Mn-bound form of SOD from S. thermophilus has a significantly higher enzymatic catalysis with respect to the Fe form. Our results suggested that SOD in S. thermophilus is more preferred to Mn, which significantly improved enzyme activity.

TABLE 3.

Effects of Mn or Fe supplement on SOD activity in engineered S. thermophilus S-3.

| Strain | Metal supplement | SOD (U/mg) ± SD |

| S-3/pKLH32 | None | 1013.1 ± 36.9 |

| 1 mmol/L Mn | 1530.1 ± 43.2 | |

| 1 mmol/L Fe | 702.6 ± 23.8 | |

| S-3/pKLH337 | None | 2651.4 ± 85.8 |

| 1 mmol/L Mn | 4723.0 ± 99.5 | |

| 1 mmol/L Fe | 2065.8 ± 64.6 |

Impact of SOD on Oxidative Stress Resistance in S. thermophilus

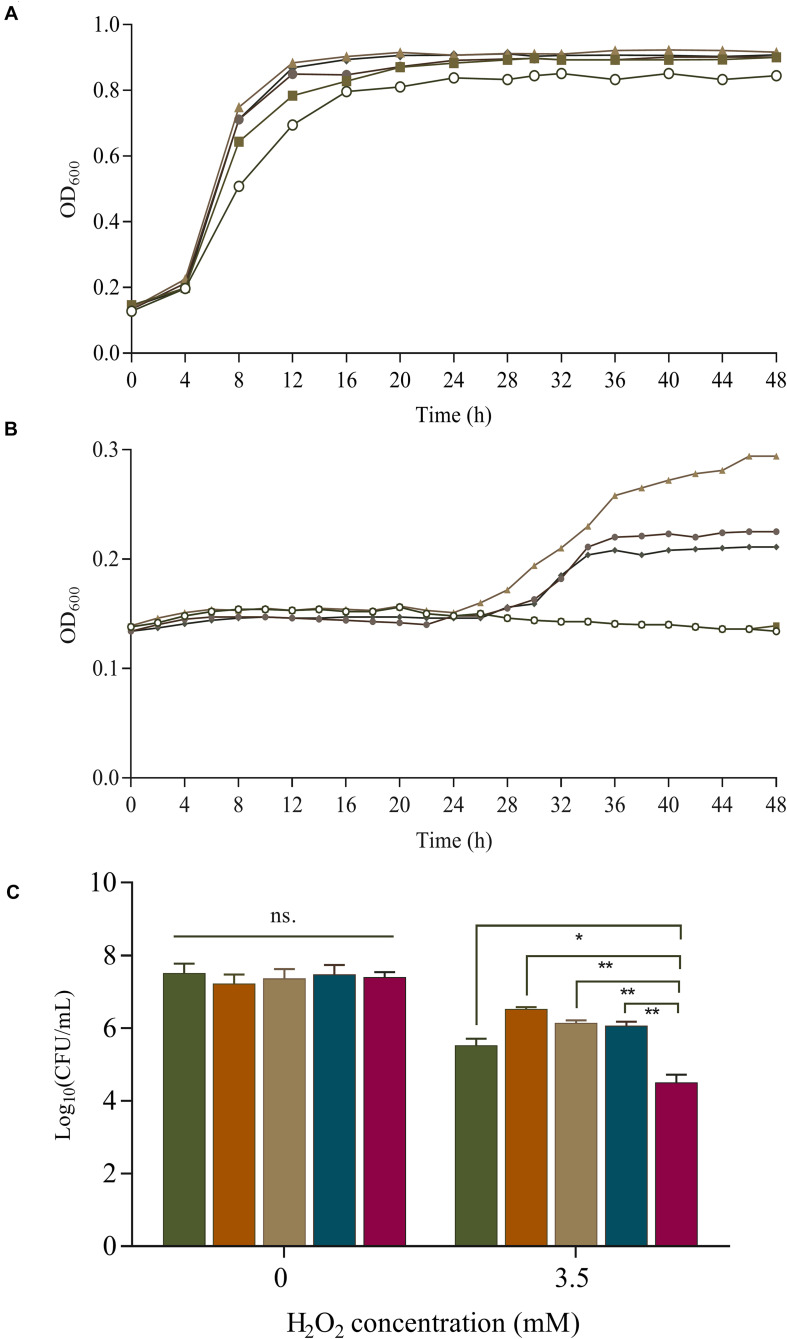

Overexpression of SOD increases the survival rate of B. longum NCC2705 under 2.5 mmol/L H2O2 stress during long-term cold storage (Zuo et al., 2014). Bruno-Barcena et al. (2004) found that the expression of sod in L. gasseri and L. acidophilus could protect against H2O2 (1.4 mmol/L) and increase their growth rate by 30% and 100%, respectively. The effect of SOD on H2O2 tolerance were investigated in our sod-overexpressing recombinants. Under aerobic condition, SOD overexpression boosted the growth of S-3/pKLH167, S-3/pKLH337, S-3/pKLH341, and S-3/pKLH344 with 1 mmol/L H2O2 treatment compared with the control strain S-3/pKLH32 (Figure 4A). Multi-copy sod recombinants S-3/pKLH337, S-3/pKLH341, and S-3/pKLH344 were able to withstand higher concentration (2.5 mmol/L) of H2O2 (Figure 4B). Our recombinants showed higher tolerance to H2O2 in comparison with other LAB such as L. plantarum and Pediococcus pentosaceus (Lin et al., 2018).

FIGURE 4.

Survival of S. thermophilus strains under oxidative stress. Effect of superoxide dismutase (SOD) expression on cell growth of recombinant strains (one to four SOD copy numbers) under 1 mmol/L (A) and 2.5 mmol/L H2O2 treatment (B). Symbols:  , Control;

, Control;  , S-3/pKLH167;

, S-3/pKLH167;  , S-3/pKLH337;

, S-3/pKLH337;  , pKLH341; and

, pKLH341; and  , pKLH344. Viable cells under 3.5 mmol/L H2O2 treatment under anaerobic conditions (C).

, pKLH344. Viable cells under 3.5 mmol/L H2O2 treatment under anaerobic conditions (C).  , pKLH167;

, pKLH167;  , pKLH337;

, pKLH337;  , pKLH341;

, pKLH341;  , pKLH344; and

, pKLH344; and  , Control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

, Control. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Oxidative stress resistance was further investigated by the survival rate under anaerobic condition. Significant difference of the survival was observed between the recombinants and the control. The survival rate of S-3/pKLH167, S-3/pKLH337, S-3/pKLH341, and S-3/pKLH344 were 73, 90, 83, and 81%, respectively, which were higher than that of wild-type (55%) under 3.5 mmol/L H2O2 (Figure 4C). The viable cells of S-3/pKLH337 was 9.5 and 97 folds higher than that of S-3/pKLH167 and S-3/pKLH32, respectively, which has the strongest antioxidant capacity among all strains. It suggested that multi-copy sod expression remarkably increases the viability of S. thermophilus under H2O2 stress. This is the first report on combining constitutive promoter library and multi-copy strategy to enhance antioxidative ability in S. thermophilus and other LAB.

For dairy fermentation, microorganisms lacking SOD is more susceptible to oxidative stress. Andrus et al. (2003) found that SOD is essential for the growth of S. thermophilus AO54 under oxidative stress. S. thermophilus with sod deficiency cannot grow aerobically. Lin et al. (2016) reported that adequacy activity of SOD might enhance resistance to H2O2 (2 mmol/L) and protect lactobacillus from oxidative stress. Bruno-Barcena et al. (2004) found that overexpression of SOD increases the growth rate from 40% to 70% compared with the wild type in L. gasseri under 1.4 mmol/L H2O2 stress. Compared with these strains, our multi-copy strains showed stronger tolerance to H2O2 (anaerobic 3.5 mmol/L and aerobic 2.5 mmol/L), indicating marked improvement of antioxidant capacity. Our result also suggested that SOD expression in LAB has great application potential in food industry.

Conclusion

S. thermophilus often suffers from inevitable oxidative stress during food production. To deal with oxidative stress, a heterologous sod was successfully expressed in S. thermophilus using a native constitutive promoter library. Moreover, the multi-copy sod strains were constructed and significantly improved the activity of SOD (2750 U/mg), which is the highest enzyme activity reported in S. thermophilus. Interestingly, compared with the control, the number of viable cells was markedly enhanced 97-fold by multi-copy sod recombinants. Therefore, it indicated that the multi-copy strategy is a reliable and efficient method for improving oxidative stress resistance in S. thermophilus.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

LA designed the experiments. LK and ZX performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. XS, YX, HZ, and YY analyzed the results. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31871776, 31972101, and 31771956), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (Grant No. 18ZR1426800), Shanghai Agriculture Applied Technology Development Program (Grant No. 2019-02-08-00-07-F01152), and Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Food Microbiology (Grant No. 19DZ2281100).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.579804/full#supplementary-material

References

- An H., Zhai Z., Yin S., Luo Y., Han B., Hao Y. (2011). Coexpression of the superoxide dismutase and the catalase provides remarkable oxidative stress resistance in Lactobacillus rhamnosus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59 3851–3856. 10.1021/jf200251k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrus J. M., Bowen S. W., Klaenhammer T. R., Hassan H. M. (2003). Molecular characterization and functional analysis of the manganese-containing superoxide dismutase gene (sodA) from Streptococcus thermophilus AO54. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 420 103–113. 10.1016/j.abb.2003.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruno-Barcena J. M., Andrus J. M., Libby S. L., Klaenhammer T. R., Hassan H. M. (2004). Expression of a heterologous manganese superoxide dismutase gene in intestinal lactobacilli provides protection against hydrogen peroxide toxicity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70 4702–4710. 10.1128/AEM.70.8.4702-4710.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. K., Hassan H. M. (1997). Characterization of superoxide dismutase in Streptococcus thermophilus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63 3732–3735. 10.1128/aem.63.9.3732-3735.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vendittis A., Amato M., Mickniewicz A., Parlato G., De Angelis A., Castellano I., et al. (2010). Regulation of the properties of superoxide dismutase from the dental pathogenic microorganism Streptococcus mutans by iron- and manganese-bound co-factor. Mol. Biosyst. 6 1973–1982. 10.1039/c003557b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vendittis A., Marco S., Di Maro A., Chambery A., Albino A., Masullo M., et al. (2012). Properties of a putative cambialistic superoxide dismutase from the aerotolerant bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus strain LMG 18311. Protein Pept. Lett. 19 333–344. 10.2174/092986612799363127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Carmen S., de Moreno de LeBlanc A., Martin R., Chain F., Langella P., Bermudez-Humaran L. G., et al. (2014). Genetically engineered immunomodulatory Streptococcus thermophilus strains producing antioxidant enzymes exhibit enhanced anti-inflammatory activities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80 869–877. 10.1128/AEM.03296-3213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L., Xiong Z., Song X., Xia Y., Zhang N., Ai L. (2019). Characterization of A Panel of Strong Constitutive Promoters from Streptococcus thermophilus for Fine-tuning Gene Expression. ACS Synthes. Biol. 8 1469–1472. 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Qiu S., Shi J., Wang S., Wang M., Xu Y., et al. (2019). A new function of copper zinc superoxide dismutase: as a regulatory DNA-binding protein in gene expression in response to intracellular hydrogen peroxide. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 5074–5085. 10.1093/nar/gkz256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Zou Y., Cao K., Ma C., Chen Z. (2016). The impact of heterologous catalase expression and superoxide dismutase overexpression on enhancing the oxidative resistance in Lactobacillus casei. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 43 703–711. 10.1007/s10295-016-1752-1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Xia Y., Wang G., Xiong Z., Zhang H., Lai F., et al. (2018). Lactobacillus plantarum AR501 Alleviates the Oxidative Stress of D-Galactose-Induced Aging Mice Liver by Upregulation of Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant Enzyme Expression. J. Food Sci. 83 1990–1998. 10.1111/1750-3841.14200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Hang X., Liu X., Tan J., Li D., Yang H. (2011). Cloning and heterologous expression of the manganese superoxide dismutase gene from Lactobacillus casei Lc18. Annu. Microbiol. 62 129–137. 10.1007/s13213-011-0237-232 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rawsthorne H., Turner K. N., Mills D. A. (2006). Multicopy integration of heterologous genes, using the lactococcal group II intron targeted to bacterial insertion sequences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 6088–6093. 10.1128/AEM.02992-2995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo Krauss I., Merlino A., Pica A., Rullo R., Bertoni A., Capasso A., et al. (2015). Fine tuning of metal-specific activity in the Mn-like group of cambialistic superoxide dismutases. RSC Adv. 5 87876–87887. 10.1039/c5ra13559a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serata M., Yasuda E., Sako T. (2018). Effect of superoxide dismutase and manganese on superoxide tolerance in Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota and analysis of multiple manganese transporters. Biosci. Microbiota. Food Health 37 31–38. 10.12938/bmfh.17-018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu M., Shen W., Yang S., Wang X., Wang F., Wang Y., et al. (2016). High-level expression and characterization of a novel serine protease in Pichia pastoris by multi-copy integration. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 92 56–66. 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen K., I, Curic-Bawden M., Junge M. P., Janzen T., Johansen E. (2016). Enhancing the Sweetness of Yoghurt through Metabolic Remodeling of Carbohydrate Metabolism in Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 82 3683–3692. 10.1128/AEM.00462-416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Xiong Z., Yang Y., Zhao N., Wang Y. (2014). Significant expression of a Chinese scorpion peptide, BmK1, in Escherichia coli through promoter engineering and gene dosage strategy. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 61 466–473. 10.1002/bab.1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z., Kong L. H., Lai P. F., Xia Y. J., Liu J. C., Li Q. Y., et al. (2019a). Comparison of gal-lac operons in wild-type galactose-positive and -negative Streptococcus thermophilus by genomics and transcription analysis. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 46 751–758. 10.1007/s10295-019-02145-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z., Kong L. H., Lai P. F., Xia Y. J., Liu J. C., Li Q. Y., et al. (2019b). Genomic and phenotypic analyses of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis in Streptococcus thermophilus S-3. J. Dairy Sci. 10.3168/jds.2018-15572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z., Guo Q., Zhang H., Wu Y., Hang X., Ai L. (2018). Exopolysaccharide produced by Streptococcus thermophiles S-3 : molecular, partial structural and rheological properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 8 1469–1472. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Z., Yang Y., Wang H., Wang G., Ren F., Li Z., et al. (2020). Global transcriptomic analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum CAUH2 in response to hydrogen peroxide stress. Food Microbiol. 87:103389. 10.1016/j.fm.2019.103389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T., Guo M., Tang Z., Zhang M., Zhuang Y., Chu J., et al. (2009). Efficient generation of multi-copy strains for optimizing secretory expression of porcine insulin precursor in yeast Pichia pastoris. J. Appl. Microbiol. 107 954–963. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04279.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo F., Yu R., Feng X., Khaskheli G. B., Chen L., Ma H., et al. (2014). Combination of heterogeneous catalase and superoxide dismutase protects Bifidobacterium longum strain NCC2705 from oxidative stress. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98 7523–7534. 10.1007/s00253-014-5851-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.