Abstract

The application of next-generation sequencing tools revealed that the cystic fibrosis respiratory tract is a polymicrobial environment. We have characterized the airway bacterial microbiota of five adult patients with cystic fibrosis during a 14-month period by 16S rRNA tag sequencing using the Illumina technology. Microbial diversity, estimated by the Shannon index, varied among patient samples collected throughout the follow-up period. The beta diversity analysis revealed that the composition of the airway microbiota was highly specific for each patient, showing little variation among the samples of each patient analyzed over time. The composition of the bacterial microbiota did not reveal any emerging pathogen predictor of pulmonary disease in cystic fibrosis or of its unfavorable clinical progress, except for unveiling the presence of anaerobic microorganisms, even without any established clinical association. Our results could potentialy help us to translate and develop strategies in response to the pathobiology of this disease, particularly because it represents an innovative approach for CF centers in Brazil.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis, Airway microbiota, Next-generation sequencing

Introduction

Chronic infection of the lower airways is the major cause of morbidity and reduced survival in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients. The progression of pulmonary disease is associated with a complex respiratory microbiota that experiences an increased worsening and succession of the infecting microorganisms [1]. Bacterial infections in the airways of these patients should be monitored not only to follow disease progression but also for therapeutic interventions that may improve the quality of life and life expectancy of the patient [2, 3].

Traditional culture-based microbiological methods demonstrate the clinical value of infections caused by “typical CF pathogens”, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Burkholderia cepacia complex, Achromobacter spp., and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, as well as the referred antibiotic therapy that is chosen to target these microrganisms [4]. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies using culture-independent methods have shown that the CF microbiome is highly diverse and represents an entangled microbial ecosystem that exceeds the complexity that was previously known based on culture-based methods [5–7]. The diversity and richness of the CF microbial community may be influenced by several factors including the age and gender of the patient, CFTR mutation type, antibiotic exposure, environmental factors, and severity of the lung disease [5–9].

In addition to the traditional isolated bacterial species documented as CF pathogens, studies employing next-generation sequencing showed complex microbial ecosystems in CF respiratory samples, including undescribed and uncultivable bacteria [10]. The diversity of the microbiota and the relative amount of each taxon have been associated with the severity of the disease in CF, with lower diversity being associated with the worst prognosis and increased airway inflammation [11]. Changes in the lung microbiome may be important in the pathophysiology of the pulmonary infection [12].

The structure and composition of the pulmonary microbiota in adults with CF exhibit decreased bacterial diversity than that of young patients, which possibly correlates with the progressive loss of the lung function and the emergence of dominant species such as P. aeruginosa, B. cepacia complex, and Achromobacter spp. [6, 13]. Besides that, several studies point out that the airways of individuals with CF present only a small number of taxa in common, demonstrating a high degree of interindividual variability in the structure and composition of the microbial community [14–16]. Understanding the changes in the microbiome over time is extremely relevant for this disease, especially in the search for a biomarker associated with an unfavorable prognosis of the clinical evolution, which could contribute to a more targeted and individualized treatment [17–21].

In this work, we examine longitudinally the airway bacterial microbiota from adult CF patients by 16S rRNA tag sequencing from DNA extracted from respiratory specimens, using Illumina technology. We verify changes in the diversity and abundance and describe the clinical evolution aspects of the CF patients. This study represents an innovative approach to CF in Brazil, with the purpose of describing the bacterial microbiota in respiratory samples using metagenomic techniques.

Methods

Patients, clinical samples, and medical record review

A total of five patients regularly monitored at the Policlínica Piquet Carneiro/Pedro Ernesto University Hospital/State University of Rio de Janeiro (PPC-HUPE-UERJ), a reference center for adult patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, were selected for the airway analysis using the criteria of having at least four consecutive sampling points between June 2014 and July 2015. During this period, sputum samples and clinical demographic data were collected according to the scheduled visits, following the clinical follow-up protocol. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital: CAAE 78893515.1.0000.5259.

Demographic information was obtained from routine medical appointments as well as the genetic profile with respect to the F508del mutation, records of the presence of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (PI), diabetes-related cystic fibrosis (DRCF), and liver disease. Regarding pulmonary function data, the predicted values for age, sex, and height of forced expiratory volume (FEV1), obtained by spirometry, were recorded. The best FEV1% values of each available exam were selected. The results were based on predicted values of the lung function for the Brazilian population [22, 23]. According to the FEV 1% value, the degree of pulmonary obstruction was classified as mild or normal (FEV1 > 70%), moderate(FEV1 > 40–70%), or severe obstruction (FEV1 ≤ 40%), according to the classification used in the CF records [24, 25]. Another disease severity indicator used was the number of hospitalizations during the study period.

DNA extraction from sputum samples, 16S rRNA tag amplification and sequencing, and microbiota analysis

Samples were fluidized in 2% N-acetyl-l-cysteine solution, treated with 2% mercaptoethanol, concentrated by centrifugation for 15 min at 10 °C at 4000 rpm and the pellet was frozen at − 80 °C. DNA was extracted with the Nucleospin Tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel, Germany). For the pre-lysis, 180 μL of lysozyme-tris-EDTA-triton solution was added to the pellets. This material was then heated at 56 °C for 1 h and 30 min after which 25 μL of proteinase K were added. Subsequently, the material was incubated at 56 °C for 3 h until complete lysis. The samples were then submitted to DNA extraction according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA was eluted with 50 μL of sterile deionized water and the concentrations were determined with a fluorescent dye on a Qubit fluorometric quantification instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Brazil).

The extracted DNA was used to amplify by PCR the V4 variable region of the 16S rRNA gene, according to Caporaso et al. (2011) [26]. The amplification reaction was done in 20 μL with the enzyme Taq AccuPrime DNA Polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen—Thermo Fisher, Brazil). PCR consisted of an initial cycle of 95 °C for 5 min followed by 25 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 1 min. A final cycle of 68 °C for 10 min completed the program. The PCR products were purified with the AMPure XP, PCR Purification system (Beckman Coulter) and quantified by fluorometry (Qubit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Three single PCR reactions for each sputum sample were performed which, after purification, were combined. Samples were then pooled and sequenced on a MiSeq instrument in a 500-cycle MiSeq reagent V2 kit (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA).

The fastq files were processed with MOTHUR, version 1.35.1 following the MiSeq SOP recommendations [27]. Briefly, paired-end reads were joined using the make contigs command and filtered to exclude ambiguities (max = 0), homopolymers (maxhomop = 8), sequences over 252 bp, and to ensure correct overlapping. Then, they were aligned against the Silva database—release 128 [28], pre-clustered (diffs = 2), and screened for chimeras, using the vsearch algorithm [29]. Screened sequences were classified, and those belonging to undesired taxa such as chloroplast, mitochondria, and Eukarya were removed. To build operational taxonomic units (OTUs), clustering was set at 97% similarity. For taxonomic description, OTUs with relative abundance lower than 1% of the total number of sequences were grouped as others. Alpha and beta diversity analysis were calculated after subsampling groups to the smallest library size. Results were plotted using GraphPad Prism v7 software (GraphPad, USA).

Results

Patient, samples collected, and medical record review

In total, 25 sputum samples collected over a 14-month period (June 2014 to July 2015) from five adult patients with CF were analyzed. The number of sputum samples per patient ranged from 4 to 6, and the time frame for sample collection per patient ranged from 287 to 378 days (average 347 days). Samples were collected according to the Laboratory Standards for Processing Microbiological Samples from People with CF from The UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust [30].

Among the five patients, three were male and two were female. The age of participants at the onset of the study varied from 18 to 32 years. One patient was homozygous and two were heterozygous for the F508del mutation, while the others presented diferent mutations. All patients showed pancreatic deficiency and two of them had diabetes. The number of hospitalizations varied from none to five. The FEV1 ranged from 22.7 to 44.4% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient information and medical review

| Patients (gender) | Birth date (month/year) | CFTR mutation 1 | CFTR mutation 2 | Sample and collection dates | BMI | Exacerbated | Antimicrobials | FEV1 (%) | Number of hospitalizations 2014/2015 | DRCF | Pancreatic insufficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient A (Female) | May/1991 | G542X | NA | 06/06/2014 (A1) | 21.77 | No | No | 37.8 | 0/0 | No | Yes |

| 05/09/2014 (A2) | 20.03 | No | No | 39.1 | |||||||

| 12/12/2014 (A3) | 21.50 | No | No | 42 | |||||||

| 13/03/2015 (A4) | 21.50 | No | No | 44.4 | |||||||

| 19/06/2015 (A5) | 21.01 | Yes | Yes (CIP OD) | NA | |||||||

| Patient B (Male) | Jun/1982 | G85E | G85E | 27/06/2014 (B1) | 17.66 | No | No | NA | 1/ 1 | Yes | Yes |

| 26/09/2014 (B2) | 17.17 | No | No | 19.1 | |||||||

| 09/01/2015 (B3) | 17.41 | No | No | 23.6 | |||||||

| 10/07/2015 (B4) | 16.8 | No | No | NA | |||||||

| Patient C (Male) | Dec/1988 | delF508 | delF508 | 18/07/2014 (C1) | 23.11 | No | No | NA | 0/0 | No | Yes |

| 05/09/2014 (C2) | ND | Yesa | Yes | NA | |||||||

| 17/10/2014 (C3) | 22.79 | Yes | No | 43 | |||||||

| 23/01/2015 (C4) | 23.8 | Yes | Yes(LVX OD) | NA | |||||||

| 29/05/2015 (C5) | 24.4 | No | No | 51.1 | |||||||

| Patient D (Female) | Jun/1981 | delF508 | R334W | 13/06/2014 (D1) | 17.86 | No | No | NA | 0/ 1 | No | Yes |

| 12/09/2014 (D2) | 17.56 | Yes | Yes (CIP OD) | 66.1 | |||||||

| 01/12/2014 (D3) | 16.96 | Yes | Yes (CIP OD + SXT OD) | 66.7 | |||||||

| 20/02/2015 (D4) | 17.21 | Yes | Yes (CAZ IV, AMK IV, OXA IV) | 65.4 | |||||||

| 27/03/2015 (D5) | NA | Nob | No | 64.2 | |||||||

| Patient E (Male) | Sep/1995 | delF508 | 3120 + G-A | 27/06/2014 (E1) | NA | Yes | NA | NA | 2/3 | Yes | Yes |

| 18/07/2014 (E2) | NA | Yes | Yes (MEM IV, AMK IV, SXT IV | NA | |||||||

| 26/09/2014 (E3) | 14.95 | Yes | No | 29 | |||||||

| 09/01/2015 (E4) | 14.80 | No | No | NA | |||||||

| 10/04/2015 (E5) | 14.03 | Yes | NA | NA | |||||||

| 10/07/2015 (E6) | 16.0 | No | NA | 22.7 |

BMI body mass index/DRCF diabetes-related cystic fibrosis/FEV1 forced expiratory volume in 1 s

ND not determined/NA not available

CIP ciprofloxacin/LVX levofloxacin/AMK amikacin/OXA oxacillin/CAZ ceftazidime/SXT trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole

OD oral dose/IV intravenous

aPatient C—hospitalized in august in a private clinic with BMI not available

bPatient D—exams collected after hospital discharge. Exacerbation: clinical deterioration (Fuchs criteria), with oral or intravenous antimicrobial prescription

Analysis of the airway microbiota and medical record

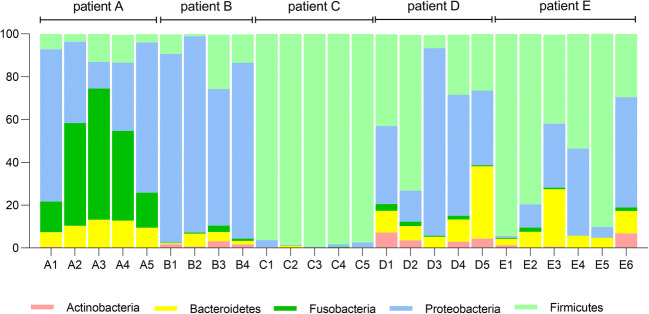

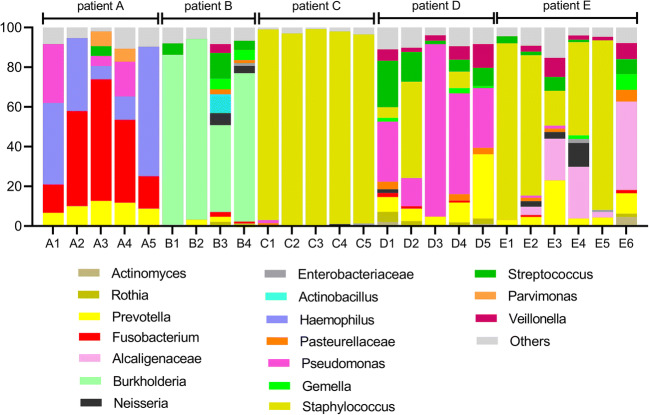

A summary of the taxonomic assignments was used to visualize changes in the microbiota over the course of the study. These community-wide profiles displayed unique features for each patient, as seen in Figs. 1 and 2 at the phylum and genus level, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Relative abundance of bacterial phyla detected in sputum samples collected from five different patients assessed by 16S rRNA V4 tag sequencing using Illumina technology. The colored segments of each bar represent the proportion of OTUs assigned to different bacterial phyla

Fig. 2.

Relative abundance of bacterial genera detected in sputum samples collected from five different patients assessed by 16S rRNA V4 tag sequencing using Illumina technology. The colored segments of each bar represent the proportion of OTUs assigned to different 20 most abundant bacterial genera present in the samples in a higher than 1% occurrence

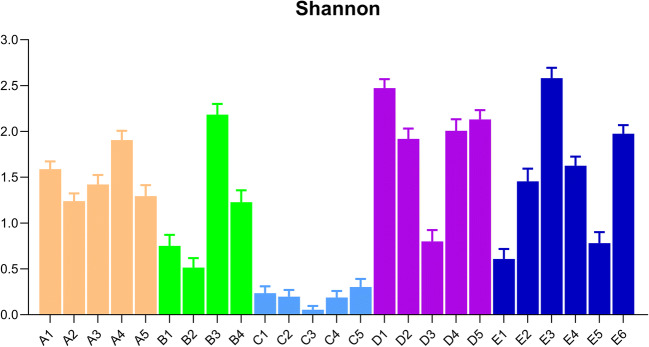

The Shannon diversity index was used to illustrate the variation in the microbiota composition among the diferent patients and their respective samples. This index combines the measure of abundance and evenness, therefore being adequate for inter-patient comparison. Figure 3 shows that the lowest diversity is exhibited by patient C, the one for which the microbiota is constantly dominated by Staphylococcus (Fig. 2). For patients A and C, the microbiota diversity is quite stable, while for patients B, D, and E there was at least one sample in which a low diversity was observed.

Fig. 3.

Shannon index showing diversity, driven by community richness (number of OTUs detected) and community evenness (relative abundance of OTUs). Each bar representes a patient sample collected over the sudy period (patients A, B, C, D, and E)

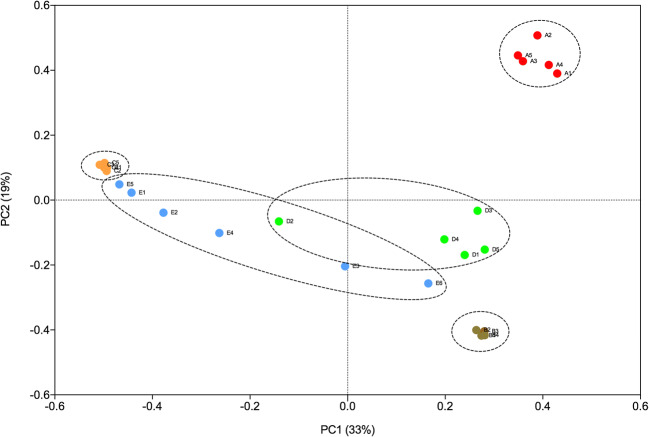

Using the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity metric, we analyzed the community composition among the different sputum samples collected from the 5 patients by means of a principal coordinate analysis (PCoA). Figure 4 shows that the bacterial communities observed in the samples from patients A, B, and C are clearly distinct from each other and from patients D and E. Furthermore, the sputum samples collected at different time-points for patients A, B, and C present a similar community composition. Samples from patient D also form a distinct cluster, with the exception of sample D2, which is located in the PCoA plot between two samples from patient E. Sample D2 differs from the others collected from this patient since it presents a high abundance of Staphylococcus (Fig. 2). Samples from patient E had more variability since they are spread through a larger area in the plot. Samples E5, E1, and E2 are close together and show a high abundance of Staphylococcus, while samples E4, E3, and E6 show significant compositional differences and are, therefore, more widely spread in the plot (Fig. 4). Notably, these samples show a high abundance of members of the Alcaligenaceae (Fig. 2).

Fig. 4.

PcoA plot of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity for bacterial communities from samples from the five patients collected at different time-points. Red circles = patient A; brown circles = patient B; orange circles = patient C; green circles = patient D; blue circles = patient E

Regarding the clinical status of patient A, the BMI was maintained in the normal range and the FEV1 did not worsen, with a slight improvement over the study period. An episode of exacerbation of the mild pulmonary disease occurred in the final collection, with no need for hospitalization (Table 1). As previously shown, the microbiota was quite stable regarding the diversity between samples (Fig. 3), presenting Haemophilus and Fusobacterium as the predominant genera during the study (Fig. 2).

Patient B maintained his BMI classified as underweight and presented FEV1 characterized by severe obstruction maintained throughout the study. At collection dates, there were no episodes of exacerbation, but there were three admissions in this period in his home city (Table 1). In the same period, DRFC was diagnosed and recurrent hemoptysis was observed. This patient presented Burkholderia as the dominant genus, but in the third collection, performed after the period of hospitalization and treatment with venous antimicrobials, a higher community diversity and a reduction in the abundance of OTUs assigned to the genus Burkholderia was observed (Fig. 2).

Patient C maintained the BMI in the normal range and presented three episodes of pulmonary exacerbation (second, third, and fourth collections), without hospitalization (Table 1). Pulmonary function was characterized by moderate obstruction. The microbiota was dominated by the genus Staphylococcus (Fig. 2) throughout the study and the diversity indexes of this patient were the lowest among the other ones (Fig. 3).

Patient D maintained the BMI (characterized as underweight) and presented three episodes of exacerbation (second, third, and fourth collections) and was hospitalized once throughout the study. The patient presented general clinical worsening in the second collection and started to receive oral antimicrobial treatment. In the following consultations (third and fourth visits), the patient presented little improvement, still with symptoms of exacerbation, and was admitted for intravenous medication (ceftazidime, amikacin, and oxacillin). The presence of the genus Pseudomonas in high relative abundance was constant during the study, except for the second sample, in which Staphylococcus was more abundant (Fig. 2).

Patient E was characterized as in a severe condition and in the year 2014 he had been transferred from the pediatric center at the Fernandes Figueira Institute (IFF-FioCruz) to the Policlínica Piquet Carneiro/Pedro Ernesto University Hospital (PPC-HUPE), a reference center for adult CF patients. The patient was characterized as presenting severe malnutrition, having maintained the same BMI throughout the study. There was a drop in FEV1, with episodes of exacerbation in five of the six collection dates (Table 1) and five hospital admissions. The patient died on Feb 5th, 2016. Patient E showed genus Staphylococcus as the most abundant in samples 1, 2, and 5 (Fig. 2).

Discussion

We describe the fluctuations in the lower airway microbiota of five adult CF patients using a 14-month follow-up period. The total bacterial microbiota was identified, and multiple taxa were detected in different abundances in the 25 samples of the five patients investigated. In general, several common pathogens (Pseudomonas, Staphylococcus, Burkholderia, Haemophilus) and rare (Rothia, Streptococcus, Neisseria, Gemella) pathogens, as well as anaerobes, were identified. Analysis of changes in the microbial community showed that the community-wide profiles display unique features for each patient as observed by studies conducted in the UK [31] and the USA [32, 33].

We highlight the presence of anaerobes in the microbiota of four of the five patients (occurring in most of the samples from patients A, B, D and E), being represented by the genera Veillonella, Prevotella, and Fusobacterium. Although the role of anaerobes in pulmonary disease in CF remains unclear, some studies showed that this group contributes to the transference of antibiotic resistance genes between microrganisms—while producing quorum sensing molecules that regulate the interspecies mediation pathways [34], and also attributed anaerobes to influence virulence characteristics in pathogens such as P. aeruginosa [35] or as potential predictive biomarkers in CF pulmonary infections such as for Porphyromonas catoniae [1].

Here, the airway microbiota of patients with CF revealed a high difference between patients and not many variations among the samples collected from each patient over time. In addition, we did not find coincidence between the longitudinally examined samples, their microbial compositions, and the clinical data (antibiotic use, spirometry, clinical symptoms, stability periods, and episodes of exacerbation of the lung function episodes). There were no specific changes in the bacterial pattern that could predict the severity or the improvement of an exacerbation. Whelan et al. 2017 [10] found no correlation whatsoever in similar studies when samples were examined longitudinally upon exacerbation onset, by using the Illumina MiSeq platform. They concluded that the exacerbation was not consistently associate with community-wide changes in the microbiome, nor with sample diversity. The association between chronic lung colonization and clinical status has been studied without a clear conclusion [36–38].

The follow-up time of this study—approximately 1 year—may have contributed to the lack of greater baseline data for the longitudinal analysis. Another possible explanation for the low correlation between the microbiome of CF sputum samples and the clinical course of the disease was the fact that the disease is driven by mucosal events that may be reflected slightly on the sputum, or that the activity of the microbiome changes independently from the bacterial load, being affected by other events, such as the expression of virulence factors, for example [39].

It is expected that certain differences between periods of clinical stability, exacerbation, and advanced disease might be found; however, we know little about the causal relationship between these modifications and the exacerbations. This lack of knowledge impairs the clinical applicability of such findings. It is important to highlight that, although we have some clinical data that show the evolution of patients, the study had a descriptive approach. Nevertheless, the airway microbiome information obtained from our group of patients was critical in the clinical decision-making about one of the individuals (patient D) whose clinical picture presented significant worsening without an explainable cause by the conventional microbiology laboratory methods. After discarding the possibility of an infection by an emergent microorganism, the NGS results that were concomitantly available at the clinical follow up indicated an increase in the relative abundance of Pseudomonas from 32% (during stability) to 85% (at exacerbation). This information was essential for decision-making, prompting clinicians to changes in the antimicrobial regimen, with an important clinical improvement in the following 8-month period [40].

Our goal is to provide data for our local reference center to cooperate with the clinical monitoring of CF airway infections. The data of microbiome itself should be interpreted with care. During the period of data analysis, we could provide some insights for clinical decision. Patient B, for example, have been followed clinically and microbiologically for 26 years. His previous history showed a chronic infection with B. vietnamiensis, but he has been clinically stable for the last 16 years with recent episodes of clinical deterioration. The genus Burkholderia was predominantly present in the microbiota of all samples analyzed by NGS in the present study, which was in concordance with the presence of B. vietnamiensis found by culture-dependent methods in the clinical laboratory. As described in a case report [41], the worsening of the prognosis was attributed to DRCF with the outcome of this patient resulting in death.

In the comparison of the pulmonary microbiome between individuals, we observed, as well as the studies by Kramer et al. (2015) [42], Coburn et al. (2016) [43], and Whelan et al. (2017) [10], the formation of highly specific patient groups, indicating that the pulmonary microbiota is unique from patient to patient. Likewise, these authors demonstrated that the CF pulmonary microbiota is prone to be more influenced by factors intrinsic to the individual than by other causes, making it necessary to be investigated by this using approach. Our results indicated that airway microbiome in CF is patient-specific.

In our study, the NGS did not reveal the presence of possible emerging pathogens that are predictors of pulmonary disease in CF or of its unfavorable clinical progress, except for revealing the presence of anaerobic microorganisms, even without any established clinical association. No coincidence was found between the findings of the microbiome and the clinical demographics of patients obtained during the follow-up period of this study. The number and length of sampling, together with clinical data granularity, may have been limiting factors for obtaining more sound data about the correspondence between intra and interpatient variation data in microbiota composition and the clinical data correspondence. However, this work emphasizes the potential of this technique for the clinical approach as it was observed for patient D.

This is the first study to use the NGS sequencing method to describe the diversity and abundance of the airway microbiota from an adult CF center in Brazil. Besides its value on incorporating knowledge and concepts to current local reference clinical microbiology laboratories, the major relevance of this study is to be a precursor in the use of microbiological analysis of airway CF microbime in our country.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the medical staff and patients from Policlínica Piquet Carneiro/ Pedro Ernesto University Hospital (PPC-HUPE), a reference center for adult patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. We thank the Bacteriology laboratory from HUPE for generous assistance in obtaining sputum samples for this study.

Funding

FAPERJ-Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro–Grant E-26/110.742/2013.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pedro Ernesto University Hospital: CAAE 78893515.1.0000.5259.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rodolpho Mattos Albano and Elizabeth Andrade Marques contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Keravec M, Jérôme M, Guilloux CA, Fangous MS, Mondot S, Vallet S, Le Berre SGR, Rault G, Férec C, Barbier G, Lepage P, Arnaud GH. Porphyromonas, a potential predictive biomarker of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pulmonary infection in cystic fibrosis. BMJ Open Resp Res. 2019;6:e000374. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2018-000374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipuma JJ. The changing microbial epidemiology in cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(2):299–323. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00068-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhagirath AY, Li Y, Somayajula D, Dadashi M, Badr S, Duan K. Cystic fibrosis lung environment and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):174. doi: 10.1186/s12890-016-0339-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauser AR, Jain M, Bar-Meir M, McColley SA. Clinical significance of microbial infection and adaptation in cystic fibrosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(1):29–70. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00036-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stressmann FA, Rogers GB, Van der Gast CJ, Marsh P, Vermeer LS, Carroll MP, Hoffman L, Daniels TW, Patel N, Forbes B, Bruce KD. Long-term cultivation-independent microbial diversity analysis demonstrates that bacterial communities infecting the adult cystic fibrosis lung show stability and resilience. Thorax. 2012;67(10):867–873. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao J, Schloss PD, Kalikin LM, Carmody LA, Foster BK, Petrosino JF, Cavalcoli JD, VanDevanter DR, Murray S, Li JZ, Young VB, LiPuma JJ. Decade-long bacterial community dynamics in cystic fibrosis airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5809–5814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120577109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahboubi MA, Carmody LA, Foster BK, Kalikin LM, VanDevanter DR, JJ LP. Culture-based and culture-independent bacteriologic analysis of cystic fibrosis respiratory specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 2016;54(3):613–619. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02299-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sibley CD, Parkins MD, Rabin HR, Duan K, Norgaard JC, Surette MG. A polymicrobial perspective of pulmonary infections exposes an enigmatic pathogen in cystic fibrosis patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(39):15070–15075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804326105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmody LA, Zhao J, Schloss PD, Petrosino JF, Murray S, Young VB, Li JZ, LiPuma JJ. Changes in cystic fibrosis airway microbiota at pulmonary exacerbation. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(3):179–187. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201211-107OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whelan FJ, Heirali AA, Rossi L, Rabin HR, Parkins MD, Surette MG. Longitudinal sampling of the lung microbiota in individuals with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoppe JE, Zemanick ET. Lessons from the lower airway microbiome in early CF. Thorax. 2017;72(12):1063–1064. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Dwyer DN, Dickson RP, Moore BB. The lung microbiome, immunity, and the pathogenesis of chronic lung disease. J Immunol. 2016;196(12):4839–4847. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox MJ, Allgaier M, Taylor B, Baek MS, Huang YJ, Daly RA, Karaoz U, Andersen GL, Brown R, Fujimura KE, Wu B, Tran D, Koff J, Kleinhenz ME, Nielson D, Brodie EL, Lynch SV. Airway microbiota and pathogen abundance in age-stratified cystic fibrosis patients. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blainey PC, Milla CE, Cornfield DN, Quake SR. Quantitative analysis of the human airway microbial ecology reveals a pervasive signature for cystic fibrosis. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(153):153ra130. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stressmann FA, Rogers GB, Marsh P, Lilley AK, Daniels TW, Carroll MP, Hoffman LR, Jones G, Allen CE, Patel N, Forbes B, Tick A, Bruce KD. Does bacterial density in cystic fibrosis sputum increase prior to pulmonary exacerbation? J Cyst Fibros. 2011;10(5):357–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delhaes L, Monchy S, Fréalle E, Hubans C, Salleron J, Prevotat A, Wallet F, Wallaert B, Dei-Cas E, Sime-Ngando T, Chabé M, Viscogliosi E. The airway microbiota in cystic fibrosis: a complex fungal and bacterial community—implications for therapeutic management. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e36313. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zemanick ET, Wagner BD, Robertson CE, Ahrens RC, Chmiel JF, Clancy JP, Gibson RL, Harris WT, Kurland G, Laguna TA, McColley SA, McCoy K, Retsch-Bogart G, Sobush KT, Zeitlin PL, Stevens MJ, Accurso FJ, Sagel SD, Harris JK. Airway microbiota across age and disease spectrum in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(5):1700832. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00832-2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carmody LA, Caverly LJ, Foster BK, MAM R, Kalikin LM, Simon RH, DR VD, JJ LP. Fluctuations in airway bacterial communities associated with clinical states and disease stages in cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2018;13(3):e0194060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossi GA, Morelli P, Gallieta LJ, Colin AA. Airway microenvironment alterations and pathogen growth incystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(4):497–506. doi: 10.1002/ppul.24246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caverly LJ, Zhao J, Li Puma JJ. Cystic fibrosis lung microbiome: opportunities to reconsider management of airway infection. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50(Suppl. 40):S31–S38. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Layeghifard M, Li H, Wang PW, Donaldson SL, Coburn B, Clark ST, Caballero JD, Zhang Y, Tullis ED, Yau YCW, Waters V, Hwang DM, Guttman D. Microbiome networks and change-point analysis reveal key community changes associated with cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2019;5:4. doi: 10.1038/s41522-018-0077-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallozi MC. Valores de referência para espirometria em crianças e adolescentes, calculados a partir de uma amostra da cidade de São Paulo. I Consenso Brasileiro sobre Espirometria. J Pneumol. 1996;22(3):1–164. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira CA, Satro T, Rodrigues SC. New reference values for forced spirometry in white adults in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33(4):397–406. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132007000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (2015) Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry 2014. pp. 1–92

- 25.GBEFC (2016) Registro Brasileiro de Fibrose Cística. p. 1–56. www. gbefc.org.br

- 26.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, Fierer N, Knight R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. PNAS 15. 2011;108(1):4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, Van Horn DJ, Weber CF. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(23):7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, Gerken J, Schweer T, Yarza P, Peplies J, Glöckner FO. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(D1):D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahé F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ. 2016;18(4):e2584. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust (2010) Microbiology laboratory standards working group. Laboratory standards for processing microbiological samples from people with cystic fibrosis. The UK Cystic Fibrosis Trust - Microbiology laboratory standards working group- Consense Document, 1st edn, 1–40

- 31.Tunney MM, Field TR, Moriarty TF, Patrick S, Doering G, Muhlebach MS, Wolfgang MC, Boucher R, Gilpin DF, McDowell A, Elborn JS. Detection of anaerobic bacteria in high numbers in sputum from patients with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:995–1001. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1151OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carmody LA, Zhao J, Kalikin LM, LeBar W, Simon RH, Venkataraman A, Schmidt TM, Abdo Z, Schloss PD, JJ LP. The daily dynamics of cystic fibrosis airway microbiota during clinical stability and at exacerbation. Microbiome. 2015;3:12. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fodor AA, Klem ER, Gilpin DF, Elborn JS, Boucher RC, Tunney MM, Wolfgang MC. The adult cystic fibrosis airway microbiota is stable over time and infection type, and highly resilient to antibiotic treatment of exacerbations. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field TR, Sibley CD, Parkins MD, Rabin HR, Surette MG. The genus Prevotella in cystic fibrosis airways. Anaerobe. 2010;16(4):337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duan K, Dammel C, Stein J, Rabin H, Surette MG. Modulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene expression by host microflora through interspecies communication. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50(5):1477–1491. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filkins LM, O'Toole GA. Cystic fibrosis lung infections: polymicrobial, complex, and hard to treat. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(12):e1005258. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frayman KB, Armstrong DS, Carzino R, Ferkol TW, Grimwood K, Storch GA, Teo SM, Wylie KM, Ranganathan SC. The lower airway microbiota in early cystic fibrosis lung disease: a longitudinal analysis. Thorax. 2017;72(12):1104–1112. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed B, Cox MJ, Cuthbertson L, James P, Cookson WOC, Davies JC, Mofatt MF, Bush A. Longitudinal development of the airway microbiota in infants with cystic fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2019;9:5143. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41597-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krause R, Moissl-Eichinger C, Halwachs B, Gorkiewicz G, Berg G, Valentin T, Prattes J, Högenauer C, Zollner-Schwetz I. Mycobiome in the lower respiratory tract—a clinical perspective. Front Microbiol. 2017;10(7):2169. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.da Costa Ferreira Leite C, de Freitas FAD, Leão RS, de Cássia Firmida M, Albano RM, Marques EA (2017) Case report: airway microbiome in CF patients and clinical evolution. Poster presentation at VI Brazilian Congress of Cystic Fibrosis

- 41.da Costa Ferreira Leite C, Folescu TW, de Cássia FM, Cohen RWF, Leão RS, de Freitas FAD, Albano RM, da Costa CH, Marques EA. Monitoring clinical and microbiological evolution of a cystic fibrosis patient over 26 years: experience of a Brazilian CF centre. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):100. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0442-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kramer R, Sauer-Heilborn A, Welte T, Jauregui R, Brettar I, Guzman CA, Höfle MG. High individuality of respiratory bacterial communities in a large cohort of adult cystic fibrosis patients under continuous antibiotic treatment. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0117436. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coburn B, Wang PW, Diaz Caballero J, Clark ST, Brahma V, Donaldson S, Zhang Y, Surendra A, Gong Y, Elizabeth Tullis D, Yau YC, Waters VJ, Hwang DM, Guttman DS. Lung microbiota across age and disease stage in cystic fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10241. doi: 10.1038/srep10241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]