Abstract

The chitinases have extensive biotechnological potential but have been little exploited commercially due to the low number of good chitinolytic microorganisms. The purpose of this study was to identify a chitinolytic fungal and optimize its production using solid state fermentation (SSF) and agroindustry substrate, to evaluate different chitin sources for chitinase production, to evaluate different solvents for the extraction of enzymes produced during fermentation process, and to determine the nematicide effect of enzymatic extract and biological control of Meloidogyne javanica and Meloidogyne incognita nematodes. The fungus was previously isolated from bedbugs of Tibraca limbativentris Stal (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) and selected among 51 isolated fungal as the largest producer of chitinolytic enzymes in SSF. The isolate UFSMQ40 has been identified as Trichoderma koningiopsis by the amplification of tef1 gene fragments. The greatest chitinase production (10.76 U gds−1) occurred with wheat bran substrate at 55% moisture, 15% colloidal chitin, 100% of corn steep liquor, and two discs of inoculum at 30 °C for 72 h. Considering the enzymatic inducers, the best chitinase production by the isolated fungus was achieved using chitin in colloidal, powder, and flakes. The usage of 1:15 g/mL of sodium citrate-phosphate buffer was the best ratio for chitinase extraction of SSF. The Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 showed high mortality of M. javanica and M. incognita when applied to treatments with enzymatic filtrated and the suspension of conidia.

Keywords: Filamentous fungi, Chitinolytic enzymes, Biopesticides, Chitin, Nematode

Introduction

Chitin is a linear polymer formed by Covalent β-(1.4) of N-acetyl-D-Glucosamine (GlcNAc), widely distributed and abundant in nature, being found as structural polysaccharide of cell walls of fungi, in the exoskeletons of arthropods, in the carapace of crustaceans, and in nematode eggs [1, 2]. Chitin degradation is mainly carried out by fungi and bacteria, which is used as a carbon and nitrogen source in their metabolism [3, 4]. The hydrolysis of chitin is performed by chitinolytic enzymes, belonging to the large family of β-glycoside hydrolase and can be divided into GlcNAc and chitinase, which differ in their patterns of cleavage [5, 6].

Recently, due to its biotechnological potential, researchers have performed studies with extracellular chitinase produced by microorganisms [1, 7, 8]. Among the numerous applications, fungal chitinase has been used in the development of biopesticides. The usefulness of fungal chitinase was observed by [9] in the hatch control of Meloidogyne javanica nematode eggs, an organism that causes major losses in agriculture. The chitinases are efficient on biological control and on the development of biopesticides with enzymatic base, being a friendly environmentally alternative for the management of agricultural pests [10, 11]. Despite the vast biotechnological potential, the chitinases have been little exploited commercially, due to the low number of organisms that exhibit high production rates, the low activity and stability of these enzymes, and the high cost of production [12, 13].

An alternative production of these enzymes is the usage of solid state fermentation (SSF), which results in low amount of residue, greater production efficiency, facility in product recovery, and low cost [12]. The SSF has also gained attention considering the possibilities for reutilization of agroindustry residues [14, 15] and consequently its bioconversion to enzyme production of industrial interest [15–17]. Besides, the use of organic substrates with low water activity, where growing conditions are similar to those from the natural habitat specially filamentous fungi, facilitates the bioconversion of lignocellulosic materials and formation of enzyme complexes responsible for the degradation of them [18].

The production of enzymes such as chitinase in SSF can be evaluated by one variable at a time. However, this approach is very laborious, and often fails to guarantee the determination of optimum conditions and does not represent the combined effect of all the variables involved [19]. One option to overcome this problem is the use of sequential experimental design methodology [18]. In this strategy, first is carried out a screening design, such as Plackett-Burmann design, to select the most significant variables in the process. In the following, a central composite rotational design may be used to the optimize the process. This tool can reduce the number and cost of experiments. Additionally, multivariate statistical tools can demonstrate interaction effects between variables, often not observed in univariate models [17]. Multivariate statistical tools have their increasing use in optimization methods, due to the favorable characteristics for production of enzymes in SSF. The response surface methodology has been extensively used to optimize culture conditions and medium composition of fermentation processes [16, 18, 20].

The production of chitinolytic enzymes in SSF is influenced by a lot of variables, such as the temperature, the carbon source, the nitrogen source, and the amount of inoculum [12, 21]. For this reason, it is necessary to optimize the chitinase production process. This optimization will be performed by applying an inexpensive waste and affordable source of carbon and nitrogen like wheat bran and corn steep liquor and chitin. Besides these, we verified the influence of temperature, moisture, and fungal inoculum in SSF. The present study is the first to report of the use of corn steep liquor for chitinase production and the utilization of filtrate enzymatic for phytopathogenic nematode control. The objectives of the current study are (i) to identify a chitinase producer microorganism and optimize its production in SSF, (ii) to evaluate different chitin sources for chitinase production, (iii) to evaluate different solvents for the extraction of enzymes produced during fermentation process, and (iv) to determine the nematicide effect of enzymatic extract and biological control of Trichoderma sp. UFSMQ40 on Meloidogyne javanica and Meloidogyne incognita nematodes species.

Material and methods

Maintenance of microorganism and pre-inoculum

The specimen Trichoderma sp. UFSMQ40 was previously isolated from bedbugs Tibraca limbativentris Stal (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) and selected among 51 isolated fungal as the largest producer of chitinolytic enzymes in SSF. The fungus was collected in Dona Francisca municipality (29°33′46.2”S 53°20′24.1”W), Rio Grande do Sul state, Brazil, during the months of June to August 2014 (winter season), in areas of rice cultivation. To obtain the discs for inoculations in SSF, the isolated fungal was peaked and cultivated for 7 days in potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 28 °C, without photoperiod.

Identification of the microorganism

For extraction of DNA the fungal was cultivated in potato-dextrose liquid medium, at 28 °C, without photoperiod for 7 days. The mycelium was triturated in microtubes with plastic pistil aid with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) reagent [22]. The genomic DNA was submitted to the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the amplification of the gene segment translation elongation factor 1α (EF). The primers for the elongation factor were EF-1 (5’-ATGGGTAAGGARGACAAGAC-3′) and EF-2 (5’-GGARGTACCAGTSATCATGTT-3′) [23]. The PCR reaction was performed using the primers in the final concentration of 0.2 μM, dNTPS at 0.2 mM, 1 U of GoTaq Green enzyme (Promega), in the final volume of 50 μL. The scheme used for the EF was: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, 40 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 40 s, and final extension at 72 °C for 4 min. The verification of amplified products was accomplished by electrophoresis in 0.8% agarose (Sigma-Aldrich®) gel stained with ethidium bromide. The amplified products were purified by precipitation with polyethylene glycol (Sigma-Aldrich®) [24] submitted to the sequencing reaction by the chain termination method using the BigDye 3.1 reagent (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed in automatic capillary sequencer 3500 XL (Applied Biosystems).

Sequenced fragments were analyzed using the Staden Package 2.0.0b software [25] for obtaining the consensus sequence. The sequence of the isolated fungal was deposited in the GenBank database and received the following number of access: KX859489. For the identification of the isolated fungal, the sequences were aligned by BioEdit software [26] using the ClustalW algorithm. Molecular identification of the isolated fungal was based on analyses of tef1 gene fragment carried out by MEGA 5.0 software [27], with the maximum likelihood analysis, for a total of 1000 repetitions for all reconstructions. The best model of nucleotide substitution to solve the data was estimated using the Model Test software [28]. For this identification, GenBank sequences from other fungi having close similarity relation were used using the tool Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

Production of colloidal chitin

The colloidal chitin was prepared; first, 4 g of powdered chitin (Sigma-Aldrich®) was suspended in 40 mL (v/w) of 37% (v/v) HCl and mixed for 50 min. Then, 1 L of ice-cold water was added dropwise. After centrifugation at 8000 g for 20 min, the pellet was collected and washed with distilled water until the pH of the washing water reached 5.0 [29].

Chitinase production

SSF were conducted in Erlenmeyer flasks of 250 mL containing 5 g of wheat bran. The quantities used for corn steep liquor (CSL), inoculum, colloidal chitin, temperature, and humidity have been described below. Each flask was covered with a hydrophilic cotton cap and autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 min. After refrigeration, inoculation was performed with 1-cm diameter disks of isolated Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 and incubated at 28 °C for 96 h in the dark. A Plackett-Burman (PB) factorial design was conducted with 12 experiments plus 3 central points (PB12) to evaluate the effects of temperature (25–35 °C), the amount of CSL (0 to 30% (w/w)), the moisture content (50–70% (w/w)), the amount of colloidal chitin (10–20% (w/w)), and the amount of inoculum (1–3) in chitinase production. Based on the analysis of data obtained in the PB12 design, a central composite rotational design (CCRD) was to evaluate the concentration effects of CSL and the moisture content in chitinase production. The remaining variables were kept fixed at the center point of the PB at 30 °C with 2 disks as inoculum and 15% (w/w) of colloidal chitin for 96 h of culture medium. In both designs, the results were submitted to the analysis of variance (ANOVA) with significance level of 0.1 using Statistica 8.0 software (StatSoft® Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA).

After SSF optimization, an experiment was conducted in order to assess the highest chitinase activity production. The amount of CSL was increased from 100 to 180% (w/w) in relation to the subtract in optimal condition of SSF applying the best performance of chitinase production considering the effect of moisture and the amount of CSL. The kinetics of chitinase production were carried out, up to 240 h of fermentation, to determine the time in which the greatest production of this enzyme occurs. The flasks were incubated in triplicates and removed every 24 h for the extraction and determination of enzyme activity, as described next. On optimized condition CCRD, the chitinolytic enzyme production was assessed using different chitin sources: powder chitin (Sigma-Aldrich®), colloidal chitin, chitin flakes (Sigma-Aldrich®), and crushed shrimp shell waste (3 mm) within 96 h in culture medium. In addition, the use of different solvents for chitinase recovery was evaluated. The following solvents were used (100 mL): acetate buffer 50 mM (pH 4.8) (Synth), sodium citrate-phosphate buffer 50 mM (pH 4.0) (Synth), Tween® 80 (Merck) (0.1%) (v/v), NaCl 0.1% (v/v) (Synth), and sterile distilled water. Subsequently, different solid/liquid (g/mL) ratios of the selected extractor were evaluated: 1:5, 1:7, 1:10, 1:12, 1:15, and 1:18. All tests were conducted on optimized condition, in triplicates, after 96 h in SSF, and the results were submitted to Scott-Knott test for the comparison of means with the significance level of 0.05, carried out by R programming language [30].

Enzyme activity

Chitinolytic enzymes were extracted from SSF samples. A dry weight fermented substrate of 5 g was extracted with 100 mL of sterile distilled water by shaking 120 rpm, at 28 °C for 1 h (adapted from Kovacs et al. [31]). Afterward, the solutions were filtered under vacuum with qualitative filter paper, and 30 mL of enzymatic extracts were stored in 50 mL tubes under freezing (4 °C) until the determination of the enzymatic activity and evaluation of the nematicide effect. Chitinolytic activity was determined using colloidal chitin previously prepared as a substrate. The amount of 1 mL of enzymatic extract was mixed with 2 mL of colloidal chitin solution 3.5% (w/v) in sodium phosphate buffer 50 mM (pH 5.2) and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. After the reaction, the quantification of reduced sugars was performed by dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) (Sigma-Aldrich®) method [32]. An aliquot of 1 mL of the reaction solution was mixed with 2 mL of DNS boiled for 5 min and cooled in an ice bath. The amount of reduced sugars produced was determined by absorbance of 540 nm using a calibration curve with GlcNAc pure (Sigma-Aldrich®). A unit of chitinase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to catalyze the formation of 1 μmol of GlcNAc per minute at 37 °C. Chitinase activity was expressed based on the dry mass of the substrate (U gds−1).

Nematicide effect

The evaluation of the nematicide effect of isolated Trichoderma sp. UFSMQ40 was performed in vitro and the enzymatic extract in the optimum condition (experiment 6 in CCRD, Table 2) on Meloidogyne javanica and Meloidogyne incognita nematode species. The suspension of conidia was obtained after 15 days of growth at 28 °C using two discs (1 cm) in culture medium containing 30 g of rice and 40 mL of distilled water, autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 min. The conidia were removed by adding 100 mL Tween® 80 (0.01%) to the culture medium and the amount of inoculum estimated in a Neubauer chamber (Kasvi). After that, the suspension was adjusted to 1*108 conidia mL−1. Following, the nematode eggs were obtained in the method [33], and the suspension of nematodes in the development stage J2 was obtained from the hatching chamber with tissue paper. From this suspension, 30 nematodes were removed per individual capture to 20 μL of water and added to 80 μL of enzymatic filtered or spore suspension containing 1*108 conidia mL−1 in 24 well cell culture plates. The control treatments consisted of the addition of 80 μL of sterile distilled water in the solution of 20 μL of water with 30 J2 nematodes. Each treatment contained five repetitions, retained at 25 °C in the dark, and the assessment of mortality was performed after 24 h to the filtered enzymatic treatments and after 72 h for the treatments with the suspension of conidia. The nematodes considered dead were captured and immersed in sterile distilled water for 24 h for confirmation of results. The efficiency of the control is determined by Abbott’s formula [34] (Eq. 1).

Table 2.

Experimental matrix of central composite rotational design to evaluate the effect of moisture and the amount of corn steep liquor (CSL) in chitinase production

| Experiment | Moisture (%) | CSL* (%) | Chitinase activity (U gds−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | (−1) 50 | (−1) 40 | 5.10 |

| E2 | (−1) 50 | (1) 80 | 8.40 |

| E3 | (1) 60 | (−1) 40 | 3.75 |

| E4 | (1) 60 | (1) 80 | 8.28 |

| E5 | (0) 55 | (−1.41) 20 | 4.20 |

| E6 | (0) 55 | (1.41) 100 | 9.42 |

| E7 | (−1,41) 40 | (0) 60 | 7.35 |

| E8 | (1,41) 70 | (0) 60 | 3.15 |

| CP9 | (0) 55 | (0) 60 | 7.35 |

| CP10 | (0) 55 | (0) 60 | 6.93 |

| CP11 | (0) 55 | (0) 60 | 6.36 |

*CSL: corn steep liquor; CP: central point; In bold is the highest chitinase activity production

| 1 |

where X is the number of live individuals in the control treatment and Y is the number of live individuals in the treatment.

Results and discussion

Identification of the microorganism

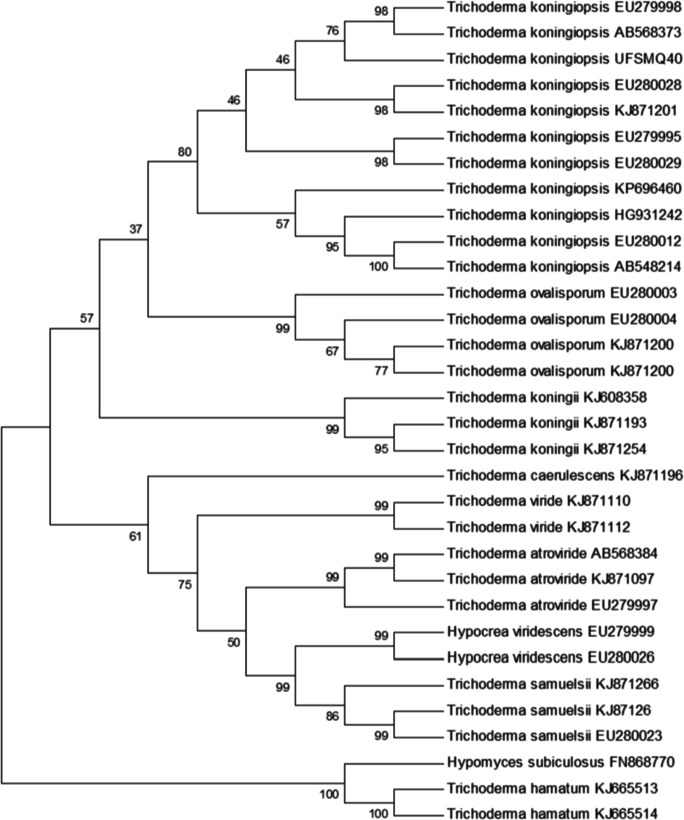

The isolated Trichoderma sp. UFSMQ40 was previously identified by the region ITS1–5.8S-ITS2 in maximum likelihood analysis as belonging to the genus Trichoderma; however its species was not possible to distinguish. Therefore, the amplification of tef1 gene fragment was performed, and further, the comparison of the species most closely related to Trichoderma sp. UFSMQ40 was performed using the BLASTn tool from the NCBI.

On maximum likelihood analysis, the isolated showed the highest similarity to the species of Trichoderma koningiopsis EU279998, T. koningiopsis AB568373, T. koningiopsis EU280028, T. koningiopsis KJ871201, T. koningiopsis EU279995, and T. koningiopsis EU280029, with high bootstrap support (80%), separating this group from other species of T. koningiopsis and confirming the identification of the isolated in this species (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Dendrogram of Trichoderma spp. obtained from the sequences of tef1 gene fragments. Maximum likelihood analysis was conducted with 1000 replicates and bootstrap values are in percent. Arm’s length does not reflect evolutionary differences. The sequences of Hypomyces subiculosus FN868770, Trichoderma hamatum KJ665513, and T. hamatum KJ665514 were used as outgroups

The ITS region of DNAr has been widely used as a reliable target for species-level identifications [35, 36]. However, in some species, this region is closely related, not being able to differentiate them [37]. The sequences of tef1 gene fragments, which encode the elongation factor, are more variables and can be used to differentiate closely related species, such as Trichoderma [35].

Optimization of solid state fermentation

Chitinase production by SSF ranged from 0.02 to 6.10 U gds−1 depending on conditions established (Table 1). The highest and the lowest production were achieved by experiment 11 and the 1, respectively.

Table 1.

Experimental matrix of Plackett-Burman (PB12) to evaluate the influence of variables on production process of chitinase in solid state fermentation (SSF) by Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40

| Experiment (E) | T* (°C) | CSL** (%) | Moisture (%) | Chitin (%) | Inoculum (disks) | CA*** (U gds−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | (+1) 35 | (−1) 0 | (+1) 70 | (−1) 10 | (−1) 1 | 0.022 |

| E2 | (+1) 35 | (+1) 30 | (−1) 50 | (+1) 20 | (−1) 1 | 2.871 |

| E3 | (−1) 25 | (+1) 30 | (+1) 70 | (−1) 10 | (+1) 3 | 1.319 |

| E4 | (+1) 35 | (−1) 0 | (+1) 70 | (+1) 20 | (−1) 1 | 0.713 |

| E5 | (+1) 35 | (+1) 30 | (−1) 50 | (+1) 20 | (+1) 3 | 5.272 |

| E6 | (+1) 35 | (+1) 30 | (+1) 70 | (−1) 10 | (+1) 3 | 3.018 |

| E7 | (−1) 25 | (+1) 30 | (+1) 70 | (+1) 20 | (−1) 1 | 5.956 |

| E8 | (−1) 25 | (−1) 0 | (+1) 70 | (+1) 20 | (+1) 3 | 0.975 |

| E9 | (−1) 25 | (−1) 0 | (−1) 50 | (+1) 20 | (+1) 3 | 1.714 |

| E10 | (+1) 35 | (−1) 0 | (−1) 50 | (−1) 10 | (+1) 3 | 0.931 |

| E11 | (−1) 25 | (+1) 30 | (−1) 50 | (−1) 10 | (−1) 1 | 6.103 |

| E12 | (−1) 25 | (−1) 0 | (−1) 50 | (−1) 10 | (−1) 1 | 3.222 |

| CP13 | (0) 30 | (0) 15 | (0) 60 | (0) 15 | (0) 2 | 2.039 |

| CP14 | (0) 30 | (0) 15 | (0) 60 | (0) 15 | (0) 2 | 2.926 |

| CP15 | (0) 30 | (0) 15 | (0) 60 | (0) 15 | (0) 2 | 1.836 |

*T: temperature; **CSL: corn steep liquor; ***CA: chitinase activity; CP: central point; In bold is the highest chitinase activity production

In order to identify the significant variables in the SSF process, the data were submitted to statistical analysis and are represented in the Pareto chart (Fig. 2). Considering the five variables applied, only CSL and moisture showed significant influence on the chitinase production. The analysis of effects indicated the increasing amount of CSL and the reduction of moisture from the culture medium conducted to an increased enzyme production (Fig. 2). In CCRD, the concentration of CSL and moisture was evaluated in the range of 20–100% (w/w) and 40–70% (w/w), respectively. Since the remaining variables did not affect the production of enzymes regardless of value employed, they were maintained as in the values of PB12 central point experiment (parameters: 15% colloidal chitin, 2 discs of inoculum, 30 °C) for 96 h in culture medium.

Fig. 2.

Pareto chart displaying the experimental parameters of Plackett-Burman to evaluate the influence of variables on solid state fermentation (SSF). (2) Corn steep liquor (CSL). (4) Colloidal chitin. (5) Inoculum (Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40). Significant level of 10%

The maximum production rate was 9.42 U gds−1 obtained in experiment 6 (Table 2) for the moisture of 55%, level (0), and 100% of CSL, level (+1.41), followed by the experiment 2 (8.40 U gds−1) for the moisture of 50%, level (−1), and 80% of CSL, level (1). Chitinase activity in average of all experiments was 6.39 U gds−1. The maximum chitinase production of the experimental matrix of CCRD represents an increase of 54% (E6 = 9.42 U gds−1, Table 2) in relation to the maximum value of experiment matrix PB12 (E11 = 6.103 U gds−1, Table 1).

The results of Table 2 were used to estimate the parameters of a quadratic model expressing chitinase production according to the independent variables (Eq. 2). Analyzing the parameters of the model (Eq. 2), it is possible to verify the increased amount of CSL led to an increase in chitinase production, while increasing the moisture has a negative effect on production. The quadratic term of moisture indicates that within the range evaluated there is a maximum point, which is the optimum value.

| 2 |

where CA is chitinase activity in U gds−1, M is the moisture, and CSL is the corn steep liquor. Significant level of 0.1.

To confirm the effect of variables on chitinase production, the above model was validated by the ANOVA (Table 3). The model presented an F-value of 3.47 times greater than the value of F-table and a R2 of 0.92, indicating that 92% of the total variation of the data is explained by the model. Thereby, the model is suitable to estimate chitinase production based on the independent variables expressed by the contour curve (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

The ANOVA of central composite rotational design experiment for production of chitinase by isolated Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40, cultivated in SSF

| Factor | SS | DF | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) CSL (L) | 28.92884 | 1 | 28.92884 | 44.09571 | 0.001167* |

| CSL (Q) | 0.01721 | 1 | 0.01721 | 0.02624 | 0.877665 |

| (2) Moisture (L) | 6.85059 | 1 | 6.85059 | 10.44223 | 0.023169* |

| Moisture (Q) | 2.97895 | 1 | 2.97895 | 4.54075 | 0.086305* |

| 1 L per 2 L | 0.37823 | 1 | 0.37823 | 0.57652 | 0.481921 |

| Error | 3.28023 | 5 | 0.65605 | ||

| Total SS | 42.85620 | 10 |

R2 = 0.92. *Significant level of 10%. Corn steep liquor (CSL)

Fig. 3.

Contour curve for optimization of chitinase production in SSF with wheat bran by Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40, considering the variables corn steep liquor versus moisture

Maximum chitinase production was achieved when the concentration of CSL was maximum (100%) and when the moisture was 55%. These results are similar to those found by Dhillon et al. [38], who have obtained 70.28 U gds−1 of chitinase activity in 55% of moisture using the isolated Aspergillus niger NRRL-567 in SSF. In addition, Thadathil et al. [39] similarly found the range of 52–56% of moisture for maximum endochitinase production by the isolated Aspergillus flavus CFR 10 e Fusarium oxysporum CFR 8.

The presence of moisture levels above the optimum required by fungus, on chitinase production by SSF, is capable of decreasing the porosity, changing the structure of substrate particles, reducing the transfer of oxygen, and increasing the formation of aerial mycelium [40].

However, low levels of moisture compromise the fungal metabolism, since it reduces the solubility of nutrients in solid substrate, reduces the degree of hydration of the substrate, and increases solid-liquid tension [40, 41]. The positive effect of CSL in chitinase production in SSF indicates this supplement can be utilized as an alternative to the use of expensive reagents such as yeast extract.

The use of industrial residue as a source of alternative nutritional in SSF is able to decrease considerable production cost of chitinase from 38 up to 73% [42, 43]. Regarding chitinase production, few studies were found using CSL as nutritional supplementation, and studies for the optimization of CSL in SSF were not found. The CSL is a residue from the industrial processing of maize, which has in its composition amino acids, vitamins, minerals [44], high carbon content (38%), and nitrogen (6.49%), all important for the metabolism of microorganisms [42]. The isolated Penicillium janthinellum P9 [45] used in culture medium under submerged fermentation with CSL as nutritional supplementation to analyze the influence of temperature, aeration, stirring, and pH for optimization of chitinase production. Additionally, Kovacs et al. [31] and Rattanakit et al. [46] verified the supplementation of standard culture medium with CSL and found no significant effect of this factor in chitinase production by fungi in SSF, although the authors used CSL along with salt solutions containing nitrogen.

The optimization of chitinase production in SSF considering CSL versus moisture in Fig. 3 showed that the model found the maximum performance at 100% of CSL based on experiment 6 of CCRD (Table 2). With the CSL, increment from 100 to 180% was able to identify that the optimal chitinase production has not increased after 100% (Fig. 4). The amount of 100% of CSL was the limit of maximum chitinase production. The chitinase production at CSL 180% presented statistical differences from the previous concentrations.

Fig. 4.

Scott-Knott test to chitinase activity produced by Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 in optimized condition of SSF with different amounts of corn steep liquor. Significance level of 5%. Bars represent the standard deviation

Influence of different chitin sources as inductor

Firstly, colloidal chitin was used to induce chitinase production by the fungus. However, obtaining colloidal chitin requires a series of steps, resulting in a massive amount of work, high cost and generating acid residues. For this reason, additional assessments were conducted in order to compare chitinase production in SSF with different enzymatic inducers. The highest enzymatic activity was achieved in the presence of chitin powder (9.72 U gds−1), followed by colloidal chitin (9.63 U gds−1), chitin flakes (9.29 U gds−1), and chitin of crushed shrimp shell (4.70 U gds−1). A larger chitinase production by Trichoderma harzianum using colloidal chitin as enzymatic inducer was found in Nampoothiri et al. [40]. The authors emphasized the facility of microorganisms to metabolize chitin due to its colloidal nature.

Colloidal chitin is the most easily assimilable chitin source by microorganisms from all forms of chitin [47]. However, the isolated Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 was used in a very similar form of powdered, colloidal, and flaked chitin, demonstrating high degradation capacity of chitin sources when the degradation difficulty increases. NK1057, NK528, and NK951 were isolated from Streptomyces sp. and observed superior chitinase production with chitin flakes as a substrate in culture medium [48]. The authors reported that although the chitin is effective as a colloidal substrate inductor, chitinase production may be extended if chitin flakes are used in the culture medium. This is due to its high crystallinity of chitin flakes, which allows initially only a gradual release of oligomers followed by suitable growth and production of enzyme [48, 49].

Time of chitinase production

Chitinase production by fungus increased progressively until it reached the maximum value of 10.76 U gds−1 at 72 h of cultivation, and afterwards the production decreased (Fig. 5). Similar result was found in Binod et al. [47]. The authors obtained maximum endochitinase production of 4.62 U gds−1 by isolated Penicillium aculeatum in 72 h and considerable reduction of production occurred subsequently at this incubation time. The decreased production, after reaching the maximum period of production at 72 h, probably occurred due to the reduction of nutrient levels in the culture medium and to enzymatic denaturation of proteases secreted by the fungus [47]. In addition, the usage of easy chitin source assimilation, such as colloidal chitin, causes a rapid enzymatic repression production, since the generation of final products is greater and faster [48].

Fig. 5.

Production of chitinase in optimized condition of SSF by Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 in the period from 0 to 240 h. Bars represent the standard deviation

Solvents for chitinase extraction

Chitinase extraction from the substrate subsequent to SSF was applied in five extractors (Fig. 6a). The sodium citrate-phosphate buffer presented the best performance, producing an extract with 9.94 U gds−1 of chitinase activity, followed by distilled water (9.38 U gds−1), with no statistical difference between these two extractors. Several studies in the literature utilized sterile distilled water as a chitinase extractor in SSF [50–55]. However, the 50 mM sodium citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 4.0) allowed greater enzymatic activity and promoted the solution stability of pH, being selected to evaluate different solid/liquid ratios in order to achieve the greatest chitinase extraction in SSF (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Scott-Knott test to chitinase activity produced by Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 in SSF (extracted with 100 mL). Enzymatic extractors: (a) citrate (50 mM sodium citrate-phosphate buffer, pH 4.0), water (sterile distilled water), Tween (Tween® 0.1%), NaCl (NaCl 0.1%), and acetate (50 mM acetate buffer, pH 4.8); (b) Sodium citrate-phosphate buffer in different solid/liquid ratios (g/mL). Significance level of 5%

The addition of 50 mM sodium citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 4.0) in 1:15 ratio resulted in higher enzymatic activity (10.15 U gds−1), statistically different from the remaining ratios. However, Patidar et al. [56] applied enzymatic extractors Tween® 80 (0.1%), NaCl (1.0%), and glycerol (3%) plus ethanol (10%), and the Tween was considered suitable for chitinase recovery produced by isolated Beauveria feline RD 101 in SSF. Superior results were observed by assessing the extractors in chitinase recovery of isolated Penicillium chrysogenum in SSF for NaCl (1.0%) [57]. The location of enzyme and the hydrophobic/hydrophilic nature of fungal mycelia, ionic bonds, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals forces appeared to determine the effectiveness of the extraction agent [58].

Nematicide effect

In the mortality of juvenile (J2), nematodes in vitro were observed after 24 h of treatment. The filtrated of Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 promoted the mortality of Meloidogyne javanica and Meloidogyne incognita nematodes with a mortality efficiency of 63.2 and 90.4%, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effectiveness of in vitro control of isolated Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 and of enzymatic extract on Meloidogyne javanica and Meloidogyne incognita

| Treatments | Control (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Meloidogyne javanica | Meloidogyne incognita | |

| Biologic control1 | 95.9 a* | 80.3 c |

| Enzymatic extract2 | 63.2 d | 90.4 b |

172 h after treatment, concentration of 1x108 conidia mL−1

224 h after treatment, chitinase activity of 10.76 U gds1

*Scott-Knott test at significance level of 10%

In addition, it was detected high mortality of these species of J2 nematodes when the conidia of isolated as a form of control was used, presenting a mortality efficiency of 95.9% in Meloidogyne javanica and 80.3% in Meloidogyne incognita, after 72 h of treatment. Similar results were found by Freitas et al. [59], who observed the filtrates of Trichoderma sp. were efficient in promoting the mortality of Meloidogyne incognita J2 nematodes in vitro. Corroborating with these results, Zhang et al. [60] observed strong lethal and parasitic effect (> 88%) in M. incognita J2 nematodes after 14 days of treatment with 1.5*107 conidia mL−1 of isolated Trichoderma longibrachiatum. No reports were found applying isolated Trichoderma koningiopsis or filtered from the culture medium to the control of nematodes. Trichoderma species are recognized by the biocontrol activity against phytopathogenic fungi and nematodes, both by antibiosis, mycoparasitism and enzymatic hydrolysis, presented by these species. In addition, promote growth and induce resistance of plants against pathogens [61].

Biotechnological contribution of chitinase production

The growing interest in fungal chitinase is due to its potential use in the production of bioactive chitooligosaccharides in the pharmaceutical area since it has better water-solubility, antioxidant, and antitumor activity than chitin [62]. Other possible usage of the chitinase is in pollution treatment, fungal protoplast generation, single-cell protein production, and degradation of shellfish waste [63]. Besides, chitinases can be explored as protoplasts for genetic engineering, in biocontrol of plant pathogenic fungi and insects [64], in the bioconversion of chitinous residues into ethanol for the biofuels industry [65], and biopesticides production for phytopathogens inhibition of fungi in agriculture.

In this study, we presented the biopesticide function of chitinase by high mortality effectiveness of phytopathogenic nematodes Meloidogyne javanica and Meloidogyne incognita. Chitinases are involved in the molecular mechanism damaging the cuticles of nematodes and insects. Corroborating with the result found in this study, Chen et al. [66] reported an efficient mortality rate (Lethal Concentration in 50% of 387.3 g/mL) using chitinases in its native state. Chitinase Pachi efficiently killed Caenorhabditis elegans by degrading the cuticle, eggshell, and intestine.

However, there are some factors that limit the wider commercial exploitation of chitinases. Despite this, this study showed the possibility of using cheap and easily found agroindustry substrates such as wheat bran and corn steep liquor. Another substrate used in our study as an inducer of chitinase production was colloidal chitin. This chitin undergoes an acid hydrolysis process and successive washes making the process time-consuming and costly. As an alternative, chitin flake was also used as an inducer because of its low-cost substrate feature maintaining the chitinase production performance. Thus, the result of this study showed that it was possible to develop a low-cost process for the production of chitinases using agroindustry residues.

Conclusion

The isolated UFSMQ40 belongs to the Trichoderma koningiopsis species. The highest production of chitinase by this fungus under the conditions evaluated in SSF occurs when the wheat bran substrate present 55% of moisture, the supplementation of CSL is 100%, the amount of colloidal chitin is at 15%, the inoculum is accomplished with 2 disks, and the incubation occurs at 30 °C for 72 h.

The colloidal chitin in powder and flakes can be used as enzymatic inducers without altering chitinase production by Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40. The addition of sodium citrate-phosphate buffer in 1:15 g:mL ratio is the best extractor evaluated for chitinase produced by this fungus under optimized conditions in SSF. Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 presents potential for industrial production of chitinase using wheat bran residues and CSL as substrates. The isolated presented high mortality effectiveness of phytopathogenic nematodes Meloidogyne javanica and Meloidogyne incognita when utilized the treatments as filtrate enzymatic and the suspension of conidia.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for providing scholarship and funding to carry out this research.

Footnotes

Highlights

• Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 presents highest production of chitinase.

• The best chitinase production was found using wheat bran substrate in 55% of moisture.

• Chitin in flakes was used as enzymatic inducers without altering chitinase production.

• Trichoderma koningiopsis UFSMQ40 offer potential for industrial chitinase production.

• The isolated fungi present high mortality effectiveness of phytopathogenic nematodes.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dahiya N, Tewari R, Hoondal GS. Biotechnological aspects of chitinolytic enzymes: a review. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;71:773–782. doi: 10.1007/s00253-005-0183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halder SK, Maity C, Jana A, Das A, Paul T, Das Mohapatra PK, Pati BR, Mondal KC. Proficient biodegradation of shrimp shell waste by Aeromonas hydrophila SBK1 for the concomitant production of antifungal chitinase and antioxidant chitosaccharides. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2013;79:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2013.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brzezinska MS, Jankiewicz U, Walczak M. Biodegradation of chitinous substances and chitinase production by the soil actinomycete Streptomyces rimosus. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2013;84:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2012.05.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merzendorfer H. The cellular basis of chitin synthesis in fungi and insects: common principles and differences. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90:759–769. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halder SK, Maity C, Jana A, Pati BR, Mondal KC. Chitinolytic enzymes from the newly isolated Aeromonas hydrophila SBK1: study of the mosquitocidal activity. BioControl. 2012;57:441–449. doi: 10.1007/s10526-011-9405-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schrank A, Vainstein MH. Metarhizium anisopliae enzymes and toxins. Toxicon. 2010;56:1267–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halder SK, Jana A, Das A, Paul T, Das Mohapatra PK, Pati BR, Mondal KC. Appraisal of antioxidant, anti-hemolytic and DNA shielding potentialities of chitosaccharides produced innovatively from shrimp shell by sequential treatment with immobilized enzymes. Food Chem. 2014;158:325–334. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.02.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patil NS, Waghmare SR, Jadhav JP. Purification and characterization of an extracellular antifungal chitinase from Penicillium ochrochloron MTCC 517 and its application in protoplast formation. Process Biochem. 2013;48:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2012.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khan A, Williams KL, Nevalainen HKM. Effects of Paecilomyces lilacinus protease and chitinase on the eggshell structures and hatching of Meloidogyne javanica juveniles. Biol Control. 2004;31:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2004.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Binod P, Sukumaran RK, Shirke SV, Rajput JC, Pandey A. Evaluation of fungal culture filtrate containing chitinase as a biocontrol agent against Helicoverpa armigera. J Appl Microbiol. 2007;103:1845–1852. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patil NS, Jadhav JP. Significance of Penicillium ochrochloron chitinase as a biocontrol agent against pest Helicoverpa armigera. Chemosphere. 2015;128:231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karthik N, Akanksha K, Pandey A. Production, purification and properties of fungal chitinases--a review. Indian J Exp Biol. 2014;52:1025–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chavan SB, Deshpande MV. Chitinolytic enzymes: an appraisal as a product of commercial potential. Biotechnol Prog. 2013;29:833–846. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliveira PC, de Brito AR, Pimentel AB, Soares GA, Pacheco CSV, Santana NB, da Silva EGP, Fernandes AG d A, Ferreira MLO, Oliveira JR, Franco M. Cocoa shell for the production of endoglucanase by Penicillium roqueforti ATCC 10110 in solid state fermentation and biochemical properties. Rev Mex Ing Química. 2019;18:777–787. doi: 10.24275/UAM/IZT/DCBI/REVMEXINGQUIM/2019V18N3/OLIVEIRA. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marques G, Silva TP, Lessa OA, de Brito AR, Reis NS, Fernandes AG d A, Ferreira MLO, Oliveira JR, Franco M. Production of xylanase and endoglucanase by solid-state fermentation of jackfruit residue. Rev Mex Ing Química. 2019;18:673–680. doi: 10.24275/uam/izt/dcbi/revmexingquim/2019v18n2/Marques. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Souza LO, de Brito AR, Bonomo RCF, Santana NB, de Almeida Antunes Ferraz JL, Aguiar-Oliveira E, de Araújo Fernandes AG, Ferreira MLO, de Oliveira JR, Franco M. Comparison of the biochemical properties between the xylanases of Thermomyces lanuginosus (Sigma®) and excreted by Penicillium roqueforti ATCC 10110 during the solid state fermentation of sugarcane bagasse. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2018;16:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2018.08.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferraz JL d AA, Souza LO, Fernandes AG d A, Oliveira MLF, de Oliveira JR, Franco M. Optimization of the solid-state fermentation conditions and characterization of xylanase produced by Penicillium roqueforti ATCC 10110 using yellow mombin residue ( Spondias mombin L.) Chem Eng Commun. 2020;207:31–42. doi: 10.1080/00986445.2019.1572000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.dos Santos TC, Filho GA, Oliveira AC, Rocha TJO, de Paula Pereira Machado F, Bonomo RCF, Mota KIA, Franco M. Application of response surface methodology for producing cellulolytic enzymes by solid-state fermentation from the puple mombin (Spondias purpurea L.) residue. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2013;22:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10068-013-0001-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Granato D, Ribeiro JCB, Castro IA, Masson ML. Sensory evaluation and physicochemical optimisation of soy-based desserts using response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2010;121:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marques GL, dos Santos Reis N, Silva TP, Ferreira MLO, Aguiar-Oliveira E, de Oliveira JR, Franco M. Production and characterisation of xylanase and endoglucanases produced by Penicillium roqueforti ATCC 10110 through the solid-state fermentation of rice husk residue. Waste Biomass Valor. 2018;9:2061–2069. doi: 10.1007/s12649-017-9994-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoykov YM, Pavlov AI, Krastanov AI. Chitinase biotechnology: production, purification, and application. Eng Life Sci. 2015;15:30–38. doi: 10.1002/elsc.201400173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL (1990) Isolation of plant DNA from fesh tissue, 1st ed., Focus

- 23.O’Donnell K, Cigelnik E. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1997;7:103–116. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitz A, Riesner D. Purification of nucleic acids by selective precipitation with polyethylene glycol 6000. Anal Biochem. 2006;354:311–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Staden R, Judge DP, Bonfield JK (2003) Analyzing sequences using the Staden Package and EMBOSS, in: Introd. to Bioinforma., Humana Press: pp. 393–410. 10.1007/978-1-59259-335-4_24

- 26.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu CL, Lan CY, Fu CC, Juang RS. Production of hexaoligochitin from colloidal chitin using a chitinase from Aeromonas schubertii. Int J Biol Macromol. 2014;69:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.R Core Team (2018) R: a language and environment for statistical Computing

- 31.Kovacs K, Szakacs G, Pusztahelyi T, Pandey A (2004) Production of chitinolytic enzymes with Trichoderma longibrachiatum IMI 92027 in solid substrate fermentation. Appl Biochem Biotechnol - Part A Enzym Eng Biotechnol, Springer:189–204. 10.1385/ABAB:118:1-3:189 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Miller GL. Use of Dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem. 1959;31:426–428. doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hussey R, Baker K (1973) Comparison of methods of collecting inocula for Meloidogyne spp., including a new technique

- 34.Abbott WS. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J Econ Entomol. 1925;18:265–267. doi: 10.1093/jee/18.2.265a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anees M, Tronsmo A, Edel-Hermann V, Hjeljord LG, Héraud C, Steinberg C. Characterization of field isolates of Trichoderma antagonistic against Rhizoctonia solani. Fungal Biol. 2010;114:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kullnig-Gradinger CM, Szakacs G, Kubicek CP. Phylogeny and evolution of the genus Trichoderma: a multigene approach. Mycol Res. 2002;106:757–767. doi: 10.1017/S0953756202006172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samuels GJ (2006) Trichoderma: Systematics, the sexual state, and ecology, in: Phytopathology: pp. 195–206. 10.1094/PHYTO-96-0195 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Dhillon GS, Brar SK, Kaur S, Valero JR, Verma M. Chitinolytic and chitosanolytic activities from crude cellulase extract produced by A. niger grown on apple pomace through Koji fermentation. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;21:1312–1321. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1106.06036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thadathil N, Kuttappan AKP, Vallabaipatel E, Kandasamy M, Velappan SP. Statistical optimization of solid state fermentation conditions for the enhanced production of thermoactive chitinases by mesophilic soil fungi using response surface methodology and their application in the reclamation of shrimp processing by-products. Ann Microbiol. 2013;64:671–681. doi: 10.1007/s13213-013-0702-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nampoothiri KM, Baiju TV, Sandhya C, Sabu A, Szakacs G, Pandey A. Process optimization for antifungal chitinase production by Trichoderma harzianum. Process Biochem. 2004;39:1583–1590. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00282-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patil NS, Jadhav JP. Enzymatic production of N-acetyl-D-glucosamine by solid state fermentation of chitinase by Penicillium ochrochloron MTCC 517 using agricultural residues. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2014;91:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2014.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berger LRR, Stamford TCM, Stamford-Arnaud TM, De Oliveira Franco L, Do Nascimento AE, Horacinna HM, Macedo RO, De Campos-Takaki GM. Effect of corn steep liquor (CSL) and cassava wastewater (CW) on chitin and chitosan production by cunninghamella elegans and their physicochemical characteristics and cytotoxicity. Molecules. 2014;19:2771–2792. doi: 10.3390/molecules19032771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hamano PS, Kilikian BV. Production of red pigments by Monascus ruber in culture media containing corn steep liquor. Braz J Chem Eng. 2006;23:443–449. doi: 10.1590/S0104-66322006000400002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nascimento R d AL, Alves MHM, Freitas JHE, Manhke LC, Luna MAC, de Santana KV, do Nascimento AE, da Silva CAA. Aproveitamento da água de maceração de milho para produção de compostos bioativos por Aspergillus niger (UCP/WFCC 1261) E-Xacta. 2015;8:15–29. doi: 10.18674/exacta.v8i1.1421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fenice M, Leuba JL, Federici F. Chitinolytic enzyme activity of Penicillium janthinellum P9 in bench-top bioreactor. J Ferment Bioeng. 1998;86:620–623. doi: 10.1016/S0922-338X(99)80020-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rattanakit N, Yang S, Wakayama M, Plikomol A, Tachiki T. Saccharification of chitin using solid-state culture of Aspergillus sp. S1-13 with shellfish waste as a substrate. J Biosci Bioeng. 2003;95:391–396. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(03)80073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Binod P, Sandhya C, Suma P, Szakacs G, Pandey A. Fungal biosynthesis of endochitinase and chitobiase in solid state fermentation and their application for the production of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine from colloidal chitin. Bioresour Technol. 2007;98:2742–2748. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nawani NN, Kapadnis BP (2005) Optimization of chitinase production using statistics based experimental designs, process Biochem

- 49.Leger RJS, Cooper RM, Charnley AK. Cuticle degrading enzymes of entomopathogenic fungi: regulation of production of chitinolytic enzymes. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:1509–1517. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-6-1509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Florido EB, Camilo PB, Mayorga-Reyes L, Cervantes RG, Cruz PM, Azaola A. β-N-Acetylglucosaminidase production by Lecanicillium (Verticillium) lecanii ATCC 26854 by solid-state fermentation utilizing shrimp shell. Interciencia. 2009;34:356–360. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barranco-Florido JE, Alatorre-Rosas R, Gutiérrez-Rojas M, Viniegra-González G, Saucedo-Castañeda G. Criteria for the selection of strains of entomopathogenic fungi Verticillium lecanii for solid state cultivation. Enzym Microb Technol. 2002;30:910–915. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(02)00032-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gkargkas K, Mamma D, Nedev G, Topakas E, Christakopoulos P, Kekos D, Macris BJ. Studies on a N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase produced by Fusarium oxysporum F3 grown in solid-state fermentation. Process Biochem. 2004;39:1599–1605. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00287-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rattanakit N, Plikomol A, Yano S, Wakayama M, Tachiki T. Utilization of shrimp shellfish waste as a substrate for solid-state cultivation of Aspergillus sp. S1–13: evaluation of a culture based on chitinase formation which is necessary for chitin-assimilation. J Biosci Bioeng. 2002;93:550–556. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(02)80236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rattanakit N, Yano S, Plikomol A, Wakayama M, Tachiki T. Purification of Aspergillus sp. S1-13 chitinases and their role in saccharification of chitin in mash of solid-state culture with shellfish waste. J Biosci Bioeng. 2007;103:535–541. doi: 10.1263/jbb.103.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rustiguel CB, Jorge JA, Guimarães LHS. Optimization of the Chitinase production by different Metarhizium anisopliae strains under solid-state fermentation with silkworm Chrysalis as substrate using CCRD. Adv Microbiol. 2012;02:268–276. doi: 10.4236/aim.2012.23032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patidar P, Agrawal D, Banerjee T, Patil S. Chitinase production by Beauveria felina RD 101: optimization of parameters under solid substrate fermentation conditions. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;21:93–95. doi: 10.1007/s11274-004-1553-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Patidar P, Agrawal D, Banerjee T, Patil S. Optimisation of process parameters for chitinase production by soil isolates of Penicillium chrysogenum under solid substrate fermentation. Process Biochem. 2005;40:2962–2967. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2005.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernández-Lahore HM, Fraile ER, Cascone O. Acid protease recovery from a solid-state fermentation system. J Biotechnol. 1998;62:83–93. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(98)00048-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Freitas MA, Pedrosa EMR, Mariano RLR, Maranhão SRVL. Screening Trichoderma spp. as potential agents for biocontrol of Meloidogyne incognita in sugarcane. Neotropica. 2012;42:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang S, Gan Y, Xu B. Biocontrol potential of a native species of Trichoderma longibrachiatum against Meloidogyne incognita. Appl Soil Ecol. 2015;94:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.apsoil.2015.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Moura Mascarin G, Ferreira M, Junior B, Vieira J, Filho A. Trichoderma harzianum reduces population of Meloidogyne incognita in cucumber plants under greenhouse conditions. J Entomol Nematol. 2012;4:54–57. doi: 10.5897/JEN12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pan M, Li J, Lv X, Du G, Liu L. Molecular engineering of chitinase from Bacillus sp. DAU101 for enzymatic production of chitooligosaccharides. Enzym Microb Technol. 2019;124:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khan FI, Bisetty K, Singh S, Permaul K, Hassan MI. Chitinase from Thermomyces lanuginosus SSBP and its biotechnological applications. Extremophiles. 2015;19:1055–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00792-015-0792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Patil RS, Ghormade V, Deshpande MV. Chitinolytic enzymes: an exploration. Enzym Microb Technol. 2000;26:473–483. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(00)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Inokuma K, Takano M, Hoshino K. Direct ethanol production from N-acetylglucosamine and chitin substrates by Mucor species. Biochem Eng J. 2013;72:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2012.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen L, Jiang H, Cheng Q, Chen J, Wu G, Kumar A, Sun M, Liu Z. Enhanced nematicidal potential of the chitinase pachi from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in association with Cry21Aa. Sci Rep. 2015;5:1–11. doi: 10.1038/srep14395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]