Abstract

EST-SSR markers were developed from Pongamia pinnata transcriptome libraries. We have successfully utilised EST-SSRs to study the genetic diversity of Indian P. pinnata germplasms and transferability study on legume plants. P. pinnata is a non-edible oil, seed-bearing leguminous tree well known for its multipurpose benefits and acts as a potential source for medicine and biodiesel preparation. Moreover, the plant is not grazable by animal and wildly grown in different agro climatic condition of India. Recently, it is much used in reforestation and rehabilitation of marginal and coal mined land in different part of India. Due to increasing demand for cultivation, understanding of the genetic diversity is important parameter for further breeding and cultivation program. In this investigation, an attempt has been undertaken to develop novel EST-SSR markers by analyzing the assembled transcriptome from previously published Illumina libraries of P. pinnata, which is cross transferrable to legume plants. Twenty EST-SSR markers were developed from oil yielding and secondary metabolite biosynthesis genes. To our knowledge, this is the first EST-SSR marker based genetic diversity study on Indian P. pinnata germplasms. The genetic diversity parameter analysis of P. pinnata showed that the Gangetic plain and Eastern India are highly diverse compared to the Central Deccan and Western germplasms. The lowest genetic diversity in the Western region may be due to the pressure of lower precipitation, high-temperature stress and reduced groundwater availability. Nevertheless, the highest genetic diversity of Gangetic plain and Eastern India may be due to the higher groundwater availability, high precipitation, higher temperature fluctuations and growing by the side of glacier-fed river water. Thus, our study shows the evidence of natural selection on the genetic diversity of P. pinnata germplasms of the Indian subcontinent.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12298-020-00889-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Climate change, Conservation genetics, Genetic diversity, Groundwater availability, Microsatellite marker, Natural selection, Transcriptome assembly

Introduction

Pongamia pinnata (Fabaceae: Karanj in Hindi) is a medium-sized fast-growing tree native to India, Malaysia, Northern Australia and Indonesia. It is known as semi mangrove tree owing to its tolerance to salt stress (Huang et al. 2012). P. pinnata is adapted to grow in temperature extremities (from a minimum of 1 °C to high 48 °C), saline water submergence, lengthy moist and dry seasons. The tree produces a large quantity of important bioactive compounds that have antibacterial, nematicidal, insecticidal, antifungal, and antiviral activities (Kesari et al. 2008, 2010a, b; Kesari and Rangan 2010). Another advantage of P. pinnata apart from its suitability as non-edible oil yielding plant is its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen through nodules, which have not been shown by other biofuel crops (willow, jatropha, castor, oil palm, canola, corn, sugarcane and sorghum). Although current energy crisis, fluctuating market prices of fuels and global warming has revived the interest in the promotion of biofuel from non-conventional sources, in spite of its economic importance the potential of P. pinnata has not been fully explored in the Indian subcontinent, mainly due to its variable and unpredictable oil yield that restricts large-scale plantation (Kesari and Rangan 2010). Hence, assessment of genetic diversity of the existing germplasm from broad eco-geography is needed for developing superior genotypes with desired traits for large scale commercial afforestation of the species (Kesari and Rangan 2010).

The earlier investigators assessed the genetic diversity of P. pinnata based on DNA markers, but the majority of surveys were often restricted by limited accessions from the individual province or local region. To our knowledge, hitherto, no investigation is carried out on genetic diversity of Indian P. pinnata germplasms based on gene-linked EST-SSR marker. The next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become the most powerful method for generating DNA markers within a short timeframe. Simple sequence repeats (SSRs) are distributed throughout the genome, including coding or genic region of the nuclear genome (Zhu et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2016). Hence, expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and transcriptome libraries are often used for SSR marker preparation (Huang et al. 2016; Ul Haq et al. 2016). Moreover, the marker derived from a transcribed portion of genes is involved in variety of metabolic functions and unveils the biological significance (Savadi et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2016). For instance, fatty acid desaturase gene is essential for jasmonate synthesis, a hormone required for thermo tolerance through induction of small heat-shock proteins, plant defence against pathogen and insects (Browse 2009) and reproductive development (McConn and Browse 1996).

EST-SSR marker developed from the oil-yielding genes and secondary metabolites may exhibit the genetic variation for the traits along with the necessary climatic condition of surrounding environments if the analysis is carried out on natural populations. For example, groundwater level could be assessed if EST-SSR markers are screened from oil yielding genes as these genes are correlated with root length (Yamauchi et al. 2015). Therefore, the present study was conducted to explore the genetic variability among the natural P. pinnata germplasms using EST-SSR markers for oil yielding genes and secondary metabolites. Transcriptome assembly was prerequisite for the mining of EST–SSRs; hence the RNAseq libraries of P. pinnata were downloaded from the NCBI for generating transcriptome assembly (Huang et al. 2012). The markers developed were assessed for their potential for cross transferability to other legume species of economic significance.

In the current study, we mined SSRs from EST databases subsequently characterized and developed 20 EST-SSR markers. These markers were utilized to evaluate the genetic variation and phylogenetic relationships of 14 P. pinnata germplasms. Our investigation revealed significant reduction in genetic diversity of Central Deccan and Western India compared to Eastern India and Gangetic plains providing significant insight into the impact of climate change for natural tree germplasm of India. Finally, we determined cross-species transferability of EST-SSR markers in legume plants.

Materials and methods

Plant material

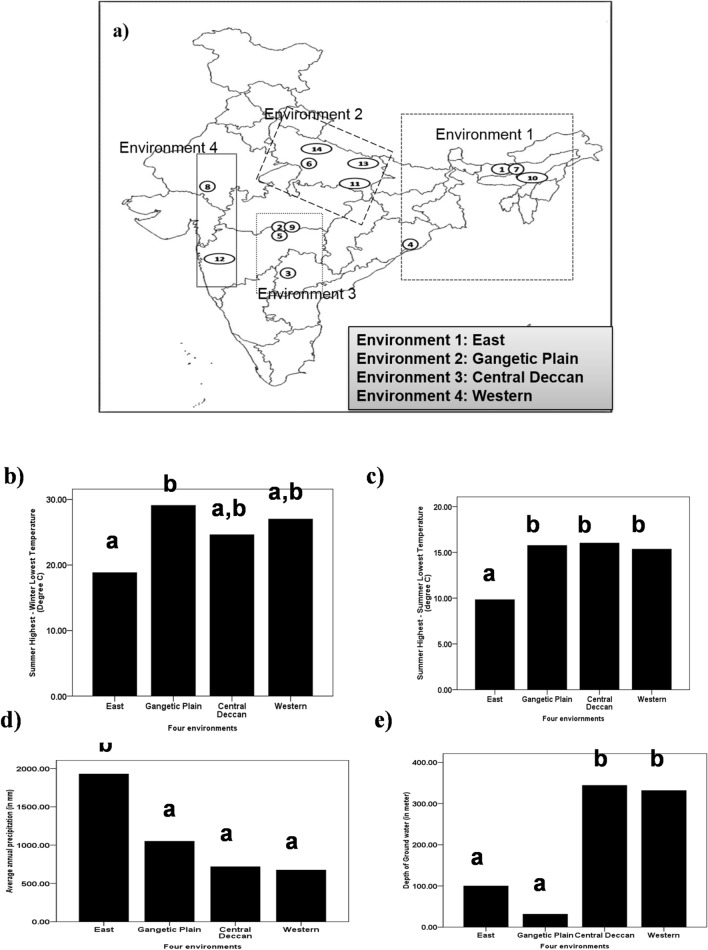

Pongamia pinnata is a diploid, cross-pollinating plant (bees, wasps and monarch butterfly are the pollinators) with an ability to grow in wide climatic conditions (deserts, river banks and seashore). In the present study, fourteen P. pinnata (PP) germplasms were collected from different climatic locations of six Indian states (Assam, Maharashtra, Orissa, Rajasthan, Telangana and Uttar Pradesh) which were clustered as four environments (Env), Env1 (East), Env2 (Gangetic plain), Env3 (Central Deccan) and Env4 (Western) (Table 1, Fig. 1a). Two other P. pinnata germplasms [CPT-29 (Candidate plus tree) and NGPP46 (North Guwahati P. pinnata)] from previously published work were also included in the current study (Kesari et al. 2008). Green leaves of the plant material were collected in duplicate and stored in zip-lock plastic bags with silica gel until DNA extraction. The significant differences in average summer (maximum) and average winter (minimum) temperature, average difference between summer (max) and summer (min) temperature were shown in Fig. 1b, c. Furthermore, the significant differences in average annual precipitation and average ground water level of the four environments were shown in Fig. 1d, e.

Table 1.

Details of accessions of P. pinnata used for diversity analysis

| S. No. | Accessions | Source | State | Latitude | Longitude | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CPT-29 | Guwahati | Assam | 26.1445169 | 91.7362365 | Bengal Assam plain |

| 2 | PP-1 | Amravati | Maharashtra | 20.9374238 | 77.7795513 | Deccan plateau |

| 3 | PP-2 | Hyderabad | Telangana | 17.385044 | 78.486671 | Deccan Telangana plateau and eastern ghat |

| 4 | PP-3 | Bhubaneswar | Orissa | 20.2356169 | 85.745673 | Eastern coastal plain |

| 5 | PP-4 | Akola | Maharashtra | 20.7059345 | 77.0219019 | Deccan plateau |

| 6 | PP-5 | Kanpur | Uttar Pradesh | 26.4148245 | 80.2321313 | Northern plain |

| 7 | NGPP-46 | Guwahati | Assam | 26.1445169 | 91.7362365 | Bengal Assam plain |

| 8 | PP-6 | Udaipur | Rajasthan | 24.585445 | 73.712479 | Northern Plain and Central Highlands including Aravallis |

| 9 | PP-7 | Melghat Tiger Reserve, Amravati | Maharashtra | 21.4030119 | 77.3268121 | Central Highlands |

| 10 | PP-8 | Silchar | Assam | 24.8332708 | 92.7789054 | North eastern hills |

| 11 | PP-9 | Banaras | Uttar Pradesh | 25.3176452 | 82.9739144 | Northern plain and central highlands including Aravali |

| 12 | PP-10 | Pune | Maharashtra | 18.5204303 | 73.8567437 | Deccan plateau |

| 13 | PP-11 | Gorakhpur | Uttar Pradesh | 26.7605545 | 83.3731675 | Eastern plain |

| 14 | PP-12 | Lucknow | Uttar Pradesh | 26.8466937 | 80.946166 | Northern plain and central highlands including Aravali |

Fig. 1.

a Map of India showing collection sites of P. pinnata germplasms from different states. Numbers mentioned on map represents the serial number of P. pinnata germplasms cited in Table 1. b Significant (P < 0.05) variation of difference in summer (max) and winter (min) temperature of four environments under this investigation, c Significant (P < 0.05) variation in average summer (max) and winter (min) temperatures of four environments, d Significant variation (P < 0.05) in average annual rainfall of four environments, e Significant variation (P < 0.05) in groundwater level of four environments under this investigation

EST-SSRs identification

P. pinnata RNAseq reads were downloaded from NCBI (SRA046342.1) (Huang et al. 2012). These reads were successfully assembled through trinity assembler in our previous investigation (Shelke and Rangan 2019). The details of RNAseq libraries are as follows: MpRs- Millettia pinnata root treated with seawater (SRR349650), MpRf- M. pinnata root treated with freshwater (SRR349651), MpLs- M. pinnata leaf treated with seawater (SRR349652) and MpLf– M. pinnata leaf treated with freshwater (SRR349653) (Huang et al. 2012) (Table 2). These assembled libraries were used for mining of microsatellite population. Microsatellite identification was carried out using MIcroSAtellite (MISA) software (http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/misa.html), a Perl script employed to detect perfect SSRs in unigene sequences. Compound SSRs (two or more SSRs in the 50 bp interval) were considered for investigation. The SSRs were considered to contain mono- to deca-nucleotide motifs. The minimum repeat unit was set to 10 for mono-nucleotides, 3 for di-nucleotides to octa-nucleotides, 2 for nona-nucleotides, and 1 for deca- nucleotide motifs, respectively.

Table 2.

Details of EST-SSRs search statistics

| S. no | Contents | MpRs | MpRf | MpLs | MpLf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total number of transcriptome sequences | 58,910 | 60,600 | 49,815 | 50,556 |

| 2 | Total number of identified SSR after annotation | 45,210 | 45,152 | 31,776 | 35,664 |

| 3 | Number of SSR containing sequences | 6840 (11.6%) | 8263 (13.7%) | 4454 (8.9%) | 4980 (9.8%) |

| 4 | Number of sequences containing more than 1 SSR | 6444 (94.2%) | 7019 (84.9%) | 4363 (97.9) % | 4925 (98.8%) |

| 5 | Number of SSRs present in compound formation | 9943 | 9299 | 7411 | 8034 |

EST-SSR sequence annotation

Unigene sequences having SSRs were employed for annotation using BLASTX search (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) with a cut-off e-value = 1e−5 against protein databases such as PLAZA 2.0 and 3.0 (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/plaza/), Swiss-Prot (http://www.expasy.ch/sprot/) and Glycine max database at Ensemble plants (plants.ensembl.org/). Additionally, all EST libraries containing SSRs were combined and further assigned to functional annotation with Panther online program (http://www.pantherdb.org/), gene ontology (GO) which classifies the sequences to molecular function, biological process, cellular component and protein class.

Designing of EST-SSR primers

The EST-SSRs loci were used to design primer using PRIMER version 3.0 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/). For designing primer pairs, simple and compound EST-SSR repeats were considered that contained mono to deca-nucleotides motifs in size. Primers were designed using Primer3 with a size ranging from 18 to 22 bp, and PCR product size ranging from 100 to 300 bp. The melting temperature (Tm) of the designed primers was 55–65 °C with 60 °C as optimum temperature. The GC content of the primers varied 40% to 60%. Twenty EST-SSR primers were developed in this current study. Four EST-SSR primers were selected from the previously published literature (Huang et al. 2016). Hence, a total of 24 primers were synthesised by Eurofins Scientific, India, for further analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Description of EST-SSR markers developed from Pongamia unigenes

| S. No. | Primer | Repeat motif | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Ta (°C) | Expected product size (bp) | Description of putative function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MPM4 | (GCT)5 |

F: CTGTTATTGTTGGGGATGATTGT R:TGCAGCAACATCAGTAAGAGAAA |

58 | 140–146 | CDS, Dihydroxyacetone kinase* (Huang et al. 2016) |

| 2 | MPM6 | (ATA)8 |

F: TTGCCAGCACTAGAGTTGTGTTA R: TCACCTGGACTAGAGATTTTCCA |

59 | 137–143 | CDS (Huang et al. 2016) |

| 3 | MPM46 | (AGA)6 |

R: CTTCCTCCCACTCTCTCATCTCT F:AACAACAGTGGAAGCAGACTCTC |

60 | 159–163 | 3′UTR (Huang et al. 2016) |

| 4 | MPM51 | (GAATT)4 |

F: CTGACACAGCCTCTTCTTCATTT R: ACCAAACTCCATTCTTCAATCAA |

58 | 144–154 | 5′UTR (Huang et al. 2016) |

| 5 | SSR11 | (TCT)3 |

F: TGCTGACTTGTTGTTTGGCG R: AGTGGCCTCAAGCTTGGTTT |

60 | 282 | Probable sphingolipid transporter spinster homolog 2* |

| 6 | SSR12 | (GTT)3 |

F: ATCTTGCTGGAAGCTGGGAC R: AGGAGTCGCAGAATTGGGTG |

60 | 188 | Mevalonate pyrophosphate decarboxylase*,** |

| 7 | SSR13 | (TG)5 |

F: TGCGGAGAATGAAACGGAGA R: AGTGATTCTGGTCGCGGAAG |

60 | 215 | CDP-diacylglycerol–inositol 3-phosphatidyltransferas* |

| 8 | SSR14 | (CTT)4 |

F: AAACCCTGGAGCAACTGCAT R: TTTCTTTGCACACAGGCTGC |

59 | 207 | 3-Oxoacyl- acyl-carrier-protein reductase 4* |

| 9 | SSR15 | (TCA)3 |

F: AACCAAGAGCACTGGCAAGA R: CATGGCGGATCTCAAGTCCA |

59 | 239 | Farnesyl diphosphate synthase*,** |

| 10 | SSR16 | (CA)4 |

F: TCATTTTTGTGCAGCACCGG R: GGAGGGGCCATAGGTTTCTG |

59 | 196 | Acetate/butyrate-CoA ligase AAE7, peroxisomal* |

| 11 | SRR17 | (GAA)3 |

F: AGCGCAATTGCATTAAGGCG R: GCTGATTTAGTTGAGGCAGCG |

59 | 260 | Putative peroxisomal acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1.2* |

| 12 | SRR18 | (AAG)3 |

F: AATGGGAGGAGCTGCAATCC R: CTCTCCAGCAACAGCCATCA |

60 | 193 | Probable 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase 14* |

| 13 | SRR19 | (GA)5 |

F: TGCCTCCCCAGAAGATTGAG R: AAGGCTGGCACCTGTTTCAT |

60 | 300 | Acyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] desaturase* |

| 14 | SRR20 | (TA)6 |

F: AACACTGGTTCTCTCGAGCG R: TGACAAGACGGAAAAGCCCA |

59 | 253 | 3-Oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein (ACP)] synthase* |

| 15 | SSR21 | (TC)5 |

F: AGCCTCCCCCTCCTTTCC R: AGAGTCTGGCGAGGGTGA |

59 | 187 | Palmitoyl-acyl carrier protein thioesterase* |

| 16 | SRR22 | (CCA)6 |

F: TCCAGCCCCTCATAGCCC R: AGATCGGGTTCGCGACAC |

59 | 203 | Oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 3C* |

| 17 | SRR23 | (GAGTCT)4 |

F: GCGTGGGGGCGGATATAT R: GGACTTCCCCATCCCTCCT |

59 | 159 | Dehydrocholesterol reductase* |

| 18 | SRR24 | (CAAA)3 |

R: CCATGGACTCGCTCCCAC F: CACCCACCAACTGCTGCT |

60 | 195 | 15-cis-phytoene desaturase** |

| 19 | SRR25 | (CT)10 |

R: TGCCTTACCCAACTGCCA F: GGAAGAGGAGGGAGAGCCA |

59 | 209 | Oxooacyl-coA reductase let-767* |

| 20 | SRR26 | (GAAGG)3 |

R: CGCGCTATCGGAGGAGAC F: CCTTTGTCTCTGTCGCTGC |

58 | 250 | Lysophospholipid acyltransferase LPEAT1* |

| 21 | SRR27 | (TCC)4 |

F: TCCATGCTAAGCCCGCTG R: GTTCACGAGCCTGCTGGT |

59 | 177 | O-acyltransferase WSD1* |

| 22 | SRR28 | (TTTA)3 |

F: TCAGCGACAATTGTGTGCT R: CCCCCAAGCCAGTGCATA |

59 | 201 | Triacylglycerol lipase SDP1* |

| 23 | SRR29 | (TCA)4 |

F: CGGCGTTTGAAAGAGCGC R: GCTGGCTTGGAGGCTATGA |

59 | 260 | Putative lipase* |

| 24 | SRR30 | (TA)5 |

F: GAGTGGTGTGGCACAGGG R: CTTCTCGCCGGTTTTCGC |

59 | 274 | Flavonoid hydroxylase, Amorpha-4,11-diene 12-monooxygenase** |

*Lipid metabolism related genes (https://www.uniprot.org/)

**Secondary metabolism related genes (https://www.uniprot.org/)

Genomic DNA extraction and quality check

The total genomic DNA was isolated from young fresh leaves of P. pinnata using modified sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) method (Kesari et al. 2009). The genomic DNA yield was determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer Tecan Infinite 200 PRO (Nanodrop Technologies, DE, USA). In addition, the quality and concentration of genomic DNA was also determined by running 1μL of DNA from each sample on a 0.8% agarose gel containing 0.5 μg/mL of ethidium bromide (EtBr).

PCR validation

PCR amplification was carried out using isolated DNA from P. pinnata germplasms in Mini Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems 9700, USA). Twenty-four EST-SSR primers were selected for PCR validation. The list of each marker, repeat type and length primer sequence and annealing temperature are mentioned in Table 3. PCR amplification was conducted in 25 μL reaction volume containing 25 ng of DNA, 2X PCR master mix pH 8.5 (Promega, USA), 400 µM dNTP, 3 mM MgCl2, nuclease-free water (Promega, USA) and 0.6 μL of 0.1–1.0 µM of each SSR forward and reverse primer. The PCR cycling was carried out in Mini Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems 9700, USA) with following conditions: 3 min at 94 °C initial denaturation followed by 35 cycles of 40 s at 94 °C, 40 s at annealing temperature (Tm), 72 °C for 40 s and the final extension of 3 min at 72 °C. The amplified PCR products were finally separated on 8% polyacrylamide gel in Tris Borate EDTA (TBE) buffer. A 50 bp size ladder (Himedia, India) was used as a reference marker. PCR amplified bands in the gel were observed under UV-trans Illuminator followed by gel documentation (Bio-Rad, USA).

Transferability of P. pinnata EST-SSR markers in different legume plants

Different legume plants (Glycine max, Cicer arietinum, Arachis hypogea, Vigna radiata and Phaseolus vulgaris) were raised from seeds within poly bags in greenhouse at Department of Biosciences and Bioengineering, Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati, Assam, India. Total genomic DNA was isolated from fresh leaves using the above mentioned modified sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS) method. Primer pairs that can amplify a clear band in P. pinnata were selected for transferability investigation. Hence, sixteen EST-SSR markers were tested for PCR amplification in different plants using the same PCR amplification protocol mentioned in the PCR validation section.

Statistical analysis of EST-SSR markers data

The EST-SSR amplified bands on polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) were scored as present (+1) and absent or missing (0) for each primer. This binary matrix was subjected to various statistical analyses. The numbers of amplified polymorphic and monomorphic PCR products were determined for each primer against fourteen P. pinnata germplasms. Polymorphic information content (PIC) value was determined to compare the efficiency of primers PIC following Botstein et al. (1980). Marker index (MI) was also determined. The EST-SSR allelic data were converted into a binary matrix, which was used to calculate the level of similarity among different germplasms. The genetic diversity among P. pinnata germplasms was computed using Dice’s coefficient (1945) (SIMQUAL program of NTSYS). Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) (Sneath and Sokal 1973) method was employed on this matrix using the SHAN subroutine through the NTSYS- pc (Numerical taxonomy system, 2.2 version) (Numerical taxonomy system, Applied Biostatistics, N.Y.). A dendrogram was generated representing the genetic relationship among fourteen P. pinnata germplasms. The correlation between the original similarity indices and cophenetic values was performed using 300 permutations to check the goodness of fit of the P. pinnata germplasms to as specific cluster in the UPGMA cluster analysis. The principal component analysis (PCA) and isolation by distance plot was generated in R software package. Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was carried out in Arlequin (version 3.01) at two level to examine the genetic difference among and within germplasms.

Results

Isolation and characterisation of EST-SSRs

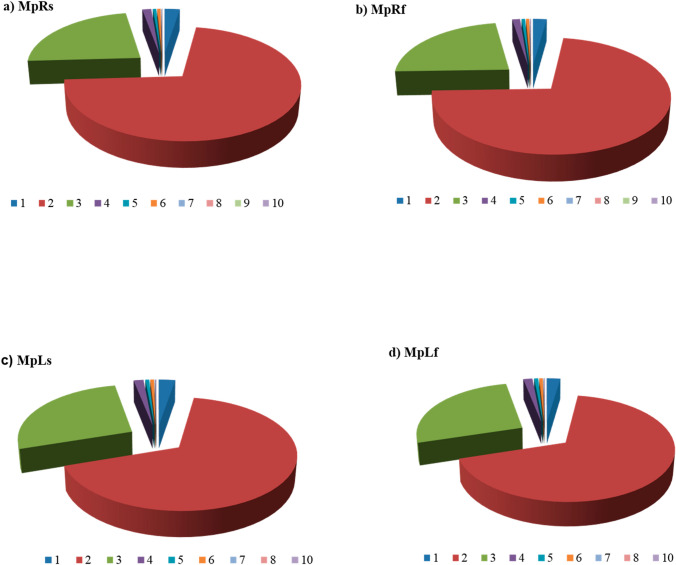

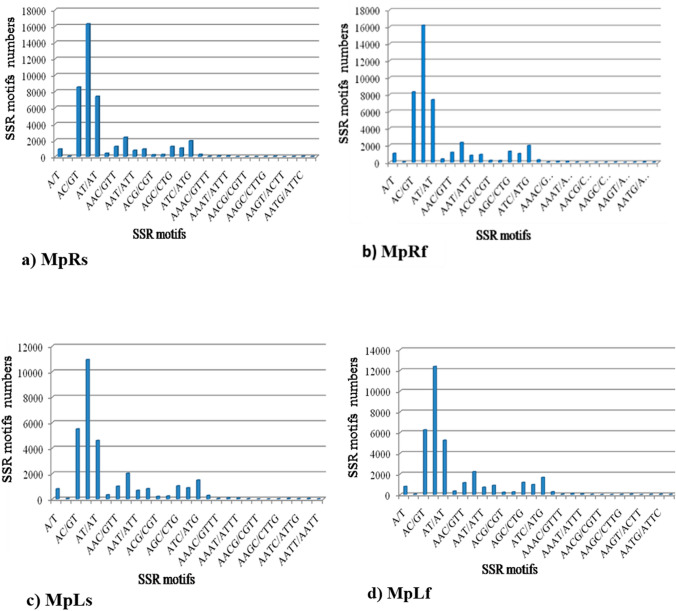

To design EST-SSR marker, we collected high throughput sequencing reads from publically available P. pinnata libraries that were assembled using Trinity assembler (Huang et al. 2012; Shelke and Rangan 2019) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/docs/toolkitsof). A total of 2,19,881 unigenes or EST sequences were examined across the four P. pinnata libraries for SSR mining. Identification and characterisation of SSR was carried out using MIcroSAtellite identification tool (Table 2). Unigene containing SSRs were annotated using BLAST program. The four libraries yielded around a total of 157802 EST-SSRs, of which 1,23,115 were simple SSRs and 34,687 SSRs were in compound formation. Across all four libraries, 8.9% to 11.6% of unigenes were determined to contain SSRs. Among these identified SSRs, 84.9% to 98.8% of unigenes contained two or more SSRs (Table 2). On an average, one microsatellite was found in every 0.98 kb of P. pinnata ESTs. The highest abundance of EST-SSRs was observed in MpRs library and the lowest abundance was found in MpRf library. Analysis revealed that the most frequent number of EST-SSRs were dinucleotide repeats (67–72%), followed by tri (23–27%), mono (2.2–2.6%), tetra (1.2–1.5%), penta and hexanucleotide (0.5-0.7%) (Fig. 2). The dominance of dinucleotide SSR repeats were observed among the analysed repeats. Among the analysed SSRs, nonanucleotide repeats were absent in MpLs and MpLf library. Among the dimeric motifs, the most frequent dinucleotide repeats motif was AG/CT (37%). Repeat motif, AC/GT was the second most abundant repeat among dinucleotide and accounted for 30% followed by AT/AT (17%). Of the total trinucleotide motifs, AAG/CTT (16%) was the most prominent repeat, which is responsible for coding leucine and lysine. The second most abundant trinucleotide motif was ATC/ATG (12%) followed by AGC/CTG (11%), respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of EST-SSRs and their classification based on microsatelite repeats in selected four libraries (Huang et al. 2012) a MpRs, b MpRf, c MpLs, d MpLf

Fig. 3.

Frequency of identified EST-SSR motifs across four libraries (Huang et al. 2012) a MpRs, b MpRf, c MpLs, d MpLf

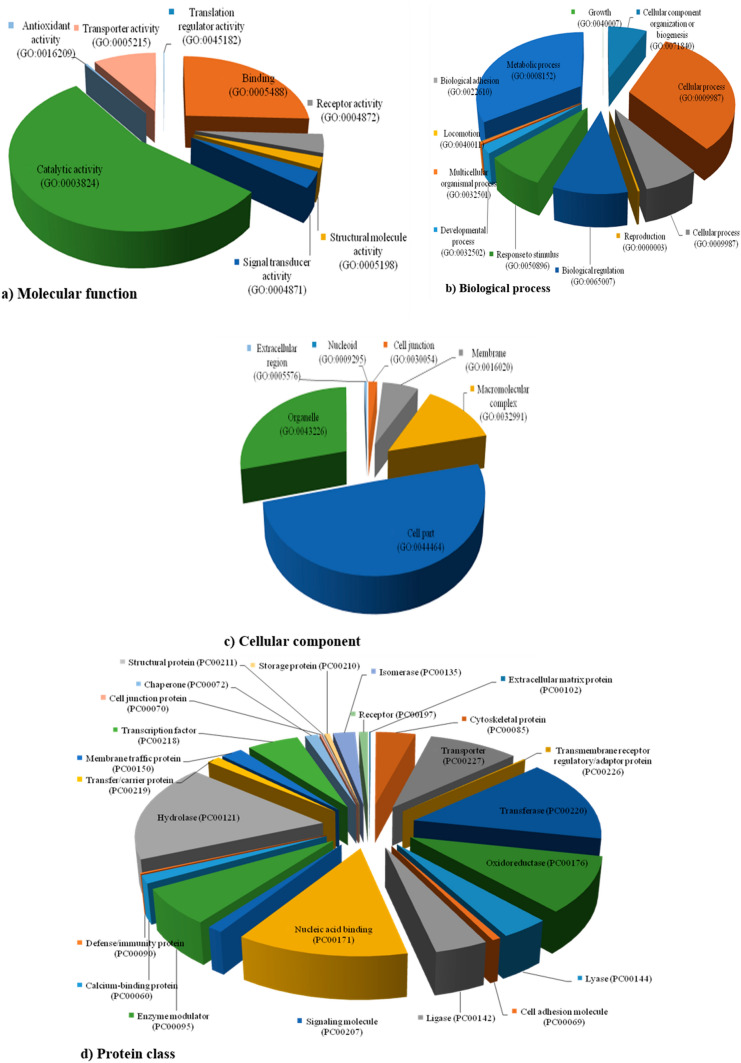

In order to assign the functional annotation, all unigene sequences having SSRs were assigned to gene ontology (GO) terms using the Panther program. SSR unigene sequences that assigned to the molecular function, biological process and cellular component clusters were classified into different terms (Fig. 4). P. pinnata EST-SSRs were assigned to various pathways of metabolic process. In molecular function category, sequences related to the catalytic activity (GO: 0003824) were high in number followed by binding sequences (GO: 0005488) (Fig. 4a). However, in the biological process section, metabolic process (GO: 0008152) related sequences were highly abundant (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, in the cellular component cluster, cell part (GO: 0044464) sequences were most abundant followed by organelle (GO: 0043226) component related sequences (Fig. 4c). Distribution of GO term in protein class revealed that the maximum sequences were associated with hydrolase (PC00121), transferase (PC00220) and least in extracellular matrix protein (PC00102) (Fig. 4d). Twenty ESTs having SSRs were developed in the current study by their involvement in the various metabolic processes and secondary metabolites biosynthesis. Apart from this, four primers were selected from an earlier publication (Huang et al. 2016) as reference EST-SSR for our investigation (Table 3).

Fig. 4.

Details of GO terms (Pie chart) assigned to P. pinnata EST-SSR. These charts represent the distribution of GO classified as a molecular function, b biological process, c cellular component, d protein class

Transferability of P. pinnata EST-SSR markers in different legume plants

The potential of EST-SSR primers was examined for cross transferability among five different legume plants. All 16 EST-SSR markers showed clear amplification in almost all selected plants. The gel picture of SSR-16 (an EST-SSR marker developed in this investigation) is shown (Supplementary Fig. 1). The estimated cross transferability was found to be 93.75% in G. max, 75% in C. arietinum, 93.75% in A. hypogaea, 100% in V. radiata, and 75% in P. vulgaris (Table 4). The SSR markers (SSR-1, 2, 4, 16, 18, 19, 20, 23, 25, 27 and 30) were regarded as highly polymorphic among the tested plant species. The transferability rate between legume plants in the present study is more than 75%. The markers SSR-26 did not produce any band except for V. radiata among all tested SSR marker.

Table 4.

Estimation of cross transferability of 16 EST-SSR primers in twelve different plants. Numbers represent bands produced with primer in different plants mentioned at the upper row

| S. No./Lane | G. max | C. arietinum | A. hypogaea | V. radiata | P. vulgaris | Primer polymorphism (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPM-4 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| MPM-6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| MPM-51 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 100 |

| SSR-12 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 66.66 |

| SSR-16 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 100 |

| SSR-18 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 100 |

| SSR-19 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 100 |

| SSR-20 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 100 |

| SSR-21 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 83.33 |

| SSR-22 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 66.66 |

| SSR-23 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 100 |

| SSR-25 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 100 |

| SSR-26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16.66 |

| SSR-27 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 9 | 100 |

| SSR-28 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 50 |

| SSR-30 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 100 |

| Transferability (%) | 93.2 | 75 | 93.25 | 100 | 75 |

Genetic diversity analysis of EST-SSR markers

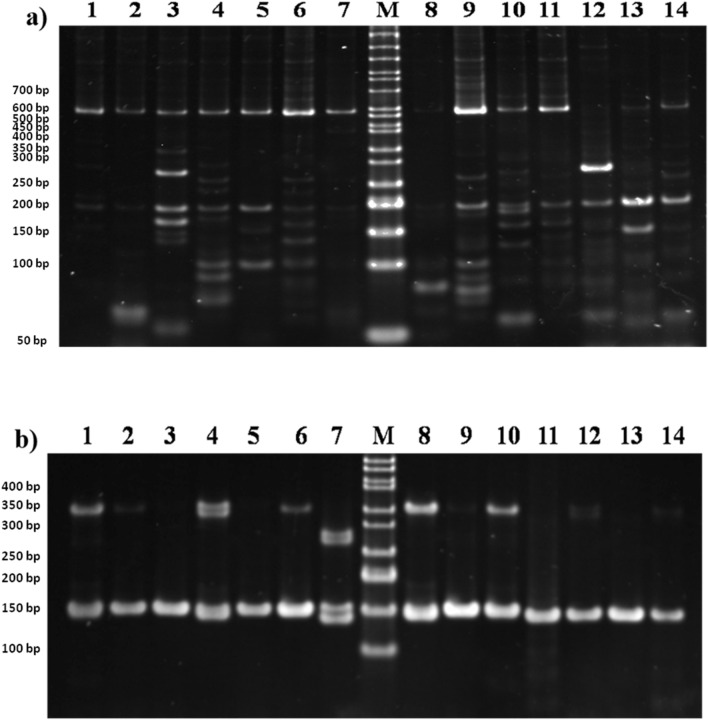

PCR amplification of EST-SSR marker was carried out using 24 primers as listed in Table 3. Of the 24 primers, 16 primers showed reproducible banding patterns among P. pinnata germplasms. Sixteen EST-SSR primers produced a total of 569 fragments of size ranging from 50 bp to 700 bp and eight primers did not produce any band under different amplification conditions. This could be possibly due to hybrid assembly, error in sequences or primer selection from the splice site at the exon–intron boundary (Dutta et al. 2011). Out of the 569 PCR bands, 224 (39.3%) bands were monomorphic, 319 (56%), bands were polymorphic, and 26 (4.5%) bands were unique in 14 P. pinnata germplasms. The highest number of bands were observed for SSR-30 (65 bands) followed by SSR-19 (61 bands) and MPM6 (51 bands). The average number of bands per primer was about 35.5, and the average number of polymorphic bands per primer was found to be 19.9. No polymorphic bands were observed in SSR-26 and 28. The highest number of monomorphic bands were found in SSR-16 (56 bands) and SSR-30 (56 bands). Of the total 26 unique bands, the highest number of bands were observed in MPM4 (6). The PIC values for EST-SSR markers varied between 0.1244 and 0.8712 for SSR-28 and SSR-25. The average PIC of EST-SSR markers was found to be 0.65 to give a high level of marker informativeness. Among the designed markers, SSR-25 exhibited the highest PIC (0.87). Besides, this marker index ranged in between 0 and 82.7 (Table 5). Previously, PIC values were classified into three categories: high (PIC > 0.5), moderate (0.25 < PIC < 0.5) and low (PIC < 0.25) (Botstein et al. 1980). Thus, the PIC of the marker developed in this investigation falls in high category (Botstein et al. 1980) which shows the effectiveness of our marker development program. The typical polymorphic and monomorphic EST-SSR fingerprinting using primer SSR-16 and SSR-23 are shown (Fig. 5a,b).

Table 5.

The degree of polymorphism and polymorphic information content (PIC) for EST-SSR primers applied to 14 accessions of P. pinnata

| Primer code | Total number of bands | Number of polymorphic bands | POL (%) |

PIC | MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPM-4 | 48 | 28 | 58.33 | 0.83 | 48.76 |

| MPM-6 | 51 | 51 | 100 | 0.80 | 80.05 |

| MPM-51 | 44 | 43 | 97.27 | 0.76 | 74.90 |

| SSR-12 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 |

| SSR-16 | 46 | 41 | 89.13 | 0.81 | 72.61 |

| SSR-18 | 41 | 39 | 95.12 | 0.83 | 79.44 |

| SSR-19 | 61 | 4 | 6.55 | 0.78 | 5.6 |

| SSR-20 | 14 | 13 | 92.85 | 0.54 | 50.21 |

| SSR-21 | 37 | 36 | 97.29 | 0.85 | 82.73 |

| SSR-22 | 19 | 5 | 26.31 | 0.38 | 10.20 |

| SSR-23 | 28 | 11 | 39.28 | 0.63 | 25.05 |

| SSR-25 | 38 | 35 | 92.10 | 0.87 | 80.24 |

| SSR-26 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0.51 | 0 |

| SSR-27 | 20 | 4 | 20 | 0.46 | 9.3 |

| SSR-28 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0.12 | 0 |

| SSR-30 | 65 | 9 | 13.84 | 0.80 | 11.18 |

| Total | 569 | 319 | |||

| Mean | 35.5 | 19.9 | 51.78 | 0.65 | 39.39 |

| Range | 51 | 51 | 100 | 0.74 | 82.73 |

Fig. 5.

Amplification of the EST-SSR markers developed in current investigation for P. pinnata germplasms from four environments of India. a PCR amplification pattern with primer SSR-16 among 14 P. pinnata germplasms. M indicated the 50 bp ladder. b PCR amplification pattern with primer SSR-23 among different P. pinnata accessions. M indicated the 50 bp ladder, the lower band—100 bp. The orientation of P. pinnata accessions on the gel is according to Table 1

Nevertheless, SSR-13, 17, 24 and 29 primers did not produce any amplification product. This could be due to the presence of large intron sequence in the flanking region that leads to disruption of PCR extension. Primer MPM-46, SSR-11, SSR-14 and SSR-15 often produced faint bands with a smear. The occurrence of a smear in the gel is due to unspecific primer binding or redundancy of primer pair sequences to target site. Some of the primers generated small size amplicon than expected size. These small sized bands may be the stutter bands or shadow bands. The generation of these small-sized bands may be due to occurrence of replication slippage during PCR amplification of microsatellite sequences.

Genetic diversity of P. pinnata from four environments of India

A remarkable difference in genetic variation was detected among P. pinnata germplasms from four environments. EST-SSR marker showed higher genetic diversity in germplasms of “Env1 and Env2” as the genetic diversity parameters were higher for these two regions. Observed number of alleles [NaEnv1 = 1.4421 ± 0.4993, NaEnv2 = 1.4526 ± 0.5004], Effective number of alleles [NbEnv1 = 1.2324 ± 0.3058, NbEnv2 = 1.2282 ± 0.2945], Nei’s gene diversity [hEnv1 = 0.1456 ± 0.1773, hEnv2 = 0.1452 ± 0.1733] and Shannon’s information index [IEnv1 = 0.2235 ± 0.2637, IEnv2 = 0.2245 ± 0.2592] of “Env1 and Env2” were much higher than genetic diversity of “Env3 and Env4” [NaEnv3 = 1.2632 ± 0.4427, NaEnv4 = 1.2789 ± 0.4877]. The lower (%PEnv3 = 26.32%, PEnv4 = 27.89%) and higher (%PEnv1 = 44.21, %PEnv2 = 45.26%) polymorphism were detected in “Env3 and Env4” and “Env1 and Env2”, respectively. The inter population differentiation (Gst) was 0.86. The average gene flow (Nm) predicted for EST-SSR markers was 2.05 (Table 6). Analysis of molecular variance (P < 0.001) of EST-SSR data showed that genetic variation (48.65%) was observed within the populations, whereas variance among the population was 51.35% (Table 7).

Table 6.

Assessment of genetic variability estimated by EST-SSR markers among four environments of P. pinnata from India

| Environment | Sample size | Observed number of alleles | Effective umber of alleles | Nei’s (1973) gene diversity | Shannon’s Information index | % P | Gst | Nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | 4 | 1.4421 ± 0.4993 | 1.2324 ± 0.3058 | 0.1456 ± 0.1773 | 0.2235 ± 0.2637 | 44.21 | ||

| Central Deccan | 4 | 1.2632 ± 0.4427 | 1.1357 ± 0.2474 | 0.0868 ± 0.1503 | 0.1340 ± 0.2288 | 26.32 | ||

| Gangetic plain | 4 | 1.4526 ± 0.5004 | 1.2282 ± 0.2945 | 0.1452 ± 0.1733 | 0.2245 ± 0.2592 | 45.26 | ||

| Western | 2 | 1.2789 ± 0.4877 | 1.2680 ± 0.2449 | 0.1570 ± 0.2020 | 0.2292 ± 0.2949 | 27.89 | ||

| Mean | 14 | 1.8842 ± 0.3217 | 1.3040 ± 0.3090 | 0.2083 ± 0.1621 | 0.1968 ± 0.1574 | 88.42 | 0.86 | 2.08 |

Table 7.

Summary of the analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) for four populationsa (total 14 accessions) of P. pinnata from India using EST-SSR data

| Markers | Source of Variation | d.f | Sum of square | Variance component | Percentage of variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among populations | 3 | 70.244 | 4.5465 | 51.35 | |

| EST-SSR | Within populations | 15 | 120.450 | 8.0660 | 48.65 |

| Total | 18 | 190.694 | 9.414 | ||

| Fixation Index FST: 0.3254 | |||||

d.f. degrees of freedom

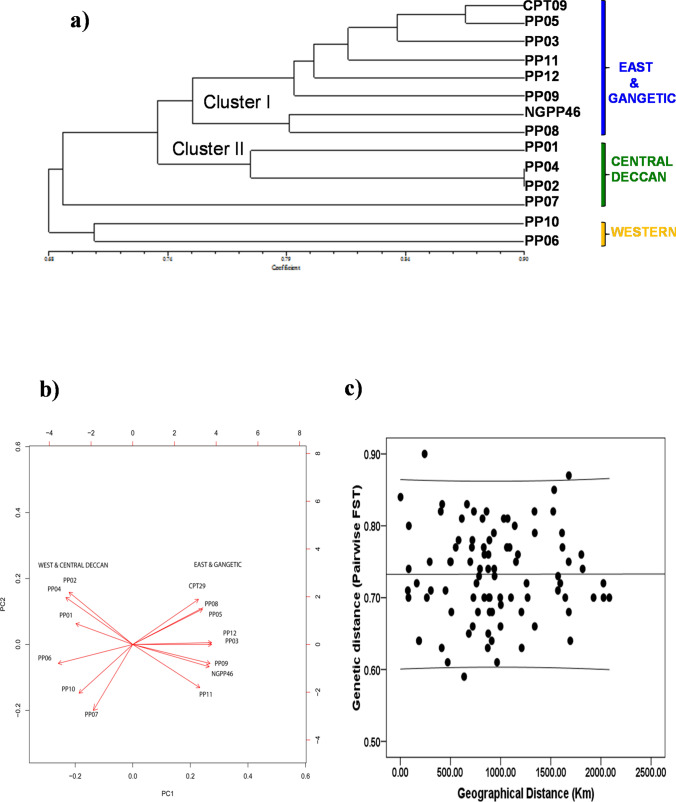

Cluster analysis, principal component analysis, isolation by distance and analyses of molecular variance

From the binary EST-SSR marker data of all markers, genetic similarity was calculated according to the Dice similarity index. Fourteen P. pinnata germplasms from four environments of India were dissected into two clusters based on 74% genetic similarity. Cluster I consisted of germplasms from “Env1 and Env2. Cluster II consisted of germplasms from “Env3 and Env4”. The germplasms of Env4 were maintaining 63% similarity with individuals from other three environments (Fig. 6a). Principal component analysis (PCA) of EST-SSR markers showed that first two components of the PCA represent 70.87% (PC1) and 16.44% (PC2) of contribution implying robust clustering. The germplasms of “Env1 and Env2” were clustered separately from the “Env3 and Env4” (Fig. 6b).The scatter plot and correlation analysis of EST-SSR markers exhibited no isolation by distance (r = − 0.001; P = 0.990) (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

Statistical representation of genetic diversity parameters for 14 P. pinnata germplasms from four environments of India. a Dendrograms representing the genetic variability among 14 germplasms of P. pinnata from India as revealed by UPGMA cluster analysis. The genetic distances were calculated from the Dice similarity coefficient. b Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of 14 P. pinnata germplasms from four environments of India based on EST-SSR marker data. PCA helped in segregating germplasms from “Western” and Central Deccan from other germplasms of India. c Scatter plot of genetic vs. geographic distance for P. pinnata and the outcome of a statistically insignificant (r = 0.001; P = 0.990) partial Mantel test

Discussion

P. pinnata is important non-edible oil yielding tree species of India that plays an important role for the production of biodiesel, fixing atmospheric nitrogen, reducing the problem of eutrophication and greenhouse gas emission. We developed and validated 16 EST-SSR markers as the first step in the creation of genomic resources. Recently, due to the accessibility of a significant amount of genomic information, a lot of EST datasets are available for many crop plants (Savadi et al. 2012; Huang et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2016). These databases have been successfully utilised to develop novel molecular markers linked to genes of agronomically important traits (Zhang et al. 2016; Ul Haq et al. 2016). Interestingly, very few EST-SSRs or gene-linked markers were developed and tested in P. pinnata (Huang et al. 2016). These facts provided the avenue to focus research on mining and development of EST-SSRs marker in P. pinnata.

To enrich P. pinnata EST-SSR repository, assembled transcriptome databases (NCBI-SRA SRP047446) were analyzed to identify 1,57,802 microsatellites (Huang et al. 2012). The frequency of SSR existence in screened sequences was one locus per 0.98 kb, which is close to some earlier reported plants like Solanum lycopersicum (1 SSRs per 1.3 Kb) and Prunus species (1 SSRs per 1.6 Kb) (Gupta et al. 2010; Sorkheh et al. 2016). In contrast, the reported density of SSRs in the present study is much higher than other legumes, such as chickpea (1 SSR per 8.54 kb) and Medicago (1 SSR per 7.47 kb) respectively (Agarwal et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014). However, these variations in EST-SSR frequency and abundance in different plant species may be due to the difference in search criteria such as the size of the dataset, type of SSR motif, and mining tools used. The present report of high abundance of dinucleotide repeats corroborates with previously conducted studies on Mentha piperita (Kumar et al. 2015). Several earlier studies have also stated the high prevalence of dinucleotide repeats in different plant species such as coffee, Lactuca Species, Jatropha and Adzuki bean (Aggarwal et al. 2006; Riar et al. 2011; Yadav et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2015). The dominance of dinucleotide SSR repeats was observed among the analysed repeats. In the current study, mononucleotide sequences were extracted which were scarcely reported previously in P. vulgaris (Garcia et al. 2011), Vigna angularis (Chen et al. 2015). Contradictory to our finding, Sreeharsha et al. (2016) reported mononucleotide (36%) repeats as the largest fraction followed by trinucleotide (31.3%) repeats in P. pinnata seed transcripts. Among the SSRs identified, mononucleotide repeats were absent in MpLs and MpLf assemblies. The presence of repeat motifs decreases with the increase in the length of repeat motif. This result is in agreement with the fact that longer repeats are less stable due to higher mutation rates (Toth et al. 2000).

The markers developed in this investigation are cross-transferable to a broad range of species with economic and commercial significance. This is in agreement with the previous investigation where a significant amount of cross-species transferability was reported (Thiel et al. 2003). A high rate of transferability of EST-SSR between the species is due to their presence in genic regions which are conserved among homologous genes. However, the transferability rate between monocot and dicot in the present study is more than 75%. Whereas, in the previous report, Savadi et al. (2012) showed the transferability of SSR motifs was about 39% between peanut (dicot) and sorghum (monocot) showing superior nature of our marker development program.

The well-established approach for commercial breeding program is the use of molecular markers for significant biological functions allowing rapid screening of genotypes. A large number of alleles detected in the current investigation warrants the suitability of developed microsatellites for genetic linkage analysis and QTL mapping of oil-yielding traits followed by marker-assisted selection in a breeding program for P. pinnata’s success in commercial afforestation program. Compared to previous genetic diversity studies, here we have opted a wide range of P. pinnata germplasms grown in different agro-climatic regions. Our study revealed that among the four studied environments of India, average summer and winter temperature fluctuation and annual precipitation, groundwater level, of Env3 and Env4 were significantly different from Env1 and Env2. The variability in groundwater of Env3 and Env4 may be due to the non-availability of rivers originating from glaciers. P. pinnata is a plant with the taproot system which is always penetrating the aquifer. Our study revealed that the natural populations of P. pinnata collected from the location where aquifers are located much deeper from the surface level along with lower variation of temperature and lower incidence of precipitation (lower humidity) were shown to exhibit lower genetic diversity compared to the plants with better groundwater availability characterised by higher precipitation, higher variation in temperature and higher humidity (Chen et al. 2006). Various types of molecular marker have been used for the evaluation of P. pinnata genetic relationship and diversity (Kesari et al. 2010a, b). Apart from the present survey, very few investigators have employed gene linked EST-SSRs for P. pinnata diversity analysis (Huang et al. 2016). Trees have longer reproductive cycles, as a result, they accumulate fewer genetic changes per unit of time compared to other plants (https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/09/090923121441.htm). Owing to the conserved nature of genic region, events responsible for microsatellite mutations occur rarely in genic regions than in non-coding regions (Chabane et al. 2005). Therefore, we opted diverse P. pinnata germplasms for EST-SSR analysis to evaluate the impact of different agroclimatic conditions. Genic regions often govern different metabolic activities in organisms, even a smallest of mutation in genic SSR may account for phenotypic changes in plants (Varshney et al. 2005). These changes can be more impactful if that genic region codes for proteins or enzymes, which are involved in multiple roles in key metabolic pathways. In this regard, even the small numbers of EST-SSRs could be helpful to analyze the genetic diversity of plants.

The phylogenetic tree and PCA showed that P. pinnata germplasms of Env3 and Env4 are forming a separate cluster showing differences in speciation on the oil-yielding traits and secondary metabolites for their decreased water availability and decreased abundance of herbivory (Metz et al. 2014). Our result is also supported by the isolation by distance analysis which showed that genetic drift rather than gene flow is the driver of speciation in P. pinnata for oil yielding genes and genes responsible for secondary metabolite synthesis. The analysis of molecular variance depicts the higher distribution of genetic variation among environments (51.35%) compared to the variation within the environments (48.65%). This might be due to the variability of the groundwater levels, variation in temperature, rainfall and humidity in each site of collection patterns (Chen et al. 2006). Moreover, gene flow among the population measured in our investigation (Nm = 2.08) was low compared to the RAPD, ISSR and AFLP markers of P. pinnata for populations of Sila forest of Guwahati, Assam (Nm = 0.60–6.28) (Kesari et al. 2010a, b). The random nature of the markers used in the previous investigation might be the possible reason for deviation in the gene flow measurement from the current investigation. The mean PIC value 0.65 is higher than the values of EST-SSRs reported in P. pinnata germplasms from China (Huang et al. 2016) but lower than that reported in the Melilotus albus (0.79) (Yan et al. 2017). The higher PIC values are probably due to screening of diverse P. pinnata germplasms from different agro climatic regions of India.

An increasing number of research articles are reporting the impact of climate change on the plants (Warner et al. 2009). The changes in the climate will increase the surface temperature of the earth by 2–4 °C with the changes in the amount and timing of precipitation (Met Office, 2011). Several problems of the climate change on tree species diversity in India would be groundwater availability, variation in temperature and precipitation dynamics (Mall et al. 2006). A changing climate can affect the groundwater availability, variation in temperature and precipitation dynamics, which results into a tree species diversity (Mall et al. 2006). Plants have acclimatized themselves against these harsh condition of nature by making alterations in a fatty acid composition, which lead to changes in the fluidity of cell membrane (Zheng et al. Zheng et al. 2011). Sixteen EST markers linked to fatty acid biosynthetic genes and secondary metabolites were used to understand the population structure of 14 natural P. pinnata germplasms which had undergone adaptation to climatic oscillation of the Indian subcontinent. Interestingly, our markers could distinguish the natural populations into two clusters based on the groundwater availability, variation in temperature and precipitation fluctuation through statistical data analyses. In future, the qualitative and quantitative profiling of oil and secondary metabolites should be linked to the EST-SSR marker analysis in P. pinnata germplasms belonging to diverse agro-climatic conditions to identify superior genotypes.

Conclusion

The gene linked EST-SSR markers developed in the present study will help to increase DNA sequence resources in P. pinnata, which were previously very low in number. The functional annotation of markers allowed us to identify the pattern and nature of SSRs in fatty acid and secondary metabolite pathway-related genes. The genetic diversity study was carried out using EST-SSR markers in 14 P. pinnata germplasms collected from the different geographical zones of India. High level of allelic and genetic diversity were found in some EST-SSR markers. These results could be useful for a breeder for exploiting variation in a natural population. EST–SSR markers revealed a high level of polymorphism and were successfully transferable across different legume plants. Transferability study provides an efficient way to conduct the genetic studies in a plant where the genomic or expression libraries are not available by reducing the cost and timing of genic primer development. Since germplasms from environments “Env1 and Env2” showed the higher percentage of average polymorphic bands, the higher amount of genetic diversity was observed in “Env1 and Env2” environments compared to germplasms belonging to other environments (“Env3 and Env4”). In conclusion, our research showed the reduction in genetic diversity that occurred in areas of lower groundwater availability and lower variation in climate.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

RGS thank Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), Government of India for student fellowship. Authors thank Department of Biosciences and Bioengineering IIT Guwahati for all infrastructural support and facilities. Thanks also to BIF facility supported by Department of Biotechnology (DBT) Govt. of India for computing facility (BT/BI/12/064/2012 NER-BIF).

Author contributions

RGS and LR conceived and designed the experiments. RGS performed the experiments; RGS and SB analyzed the data. LR contributed to reagents/materials/analysis tools. LR, RGS and SB wrote the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agarwal G, Jhanwar S, Priya P, Singh VK, Saxena MS, Parida SK, Garg R, Tyagi AK, Jain M. Comparative analysis of kabuli chickpea transcriptome with desi and wild chickpea provides a rich resource for development of functional markers. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal RK, Hendre PS, Varshney RK, Bhat PR, Krishnakumar V, Singh L. Identification, characterization and utilization of EST-derived genic microsatellite markers for genome analyses of coffee and related species. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;114:359. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0440-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botstein D, White RL, Skolnick M, Davis RW. Construction of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am J Hum Genet. 1980;32:314–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browse J. Jasmonate passes muster: a receptor and targets for the defence hormone. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:183–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabane K, Ablett GA, Cordeiro GM, Valkounn J, Henry RJ. EST versus genomic derived microsatellite markers for genotyping wild and cultivated barley. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2005;52:903–909. doi: 10.1007/s10722-003-6112-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YN, Zilliacus H, Li WH, Zhang HF, Chen YP. Ground-water level affects plant species diversity along the lower reaches of the Tarim river, Western China. J Arid Environ. 2006;66:231–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2005.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Liu L, Wang L, Wang S, Somta P, Cheng X. Development and validation of EST-SSR markers from the transcriptome of adzuki bean (Vigna angularis) PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0131939. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Kumawat G, Singh BP, Gupta DK, Singh S, Dogra V, Gaikwad K, Sharma TR, Raje RS, Bandhopadhya TK, Datta S, Singh MN, Bashasab F, Kulwal P, Wanjari KB, Varshney R, Cook DR, Singh NK. Development of genic-SSR markers by deep transcriptome sequencing in pigeonpea [Cajanus cajan L.) Millspaugh] BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia RA, Rangel PN, Brondani C, Martins WS, Melo LC, Carneiro MS, Borba TC, Brondani RP. The characterization of a new set of EST-derived simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers as a resource for the genetic analysis of Phaseolus vulgaris. BMC Genet. 2011;12:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-12-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Tripathi KP, Roy S, Sharma A. Analysis of unigene derived microsatellite markers in family solanaceae. Bioinformation. 2010;5:113–121. doi: 10.6026/97320630005113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Lu X, Yan H, Chen S, Zhang W, Huang R, Zheng Y. Transcriptome characterization and sequencing-based identification of salt-responsive genes in Millettia pinnata, a semi-mangrove plant. DNA Res. 2012;19:195–207. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dss004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Guo X, Hao X, Zhang W, Chen S, Huang R, Gresshoff PM, Zheng Y. De novo sequencing and characterization of seed transcriptome of the tree legume Millettia pinnata for gene discovery and SSR marker development. Mol Breed. 2016;36:75. doi: 10.1007/s11032-016-0503-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesari V, Rangan L. Development of Pongamia pinnata as an alternative biofuel crop-current status and scope of plantations in India. J Crop Sci Biotechnol. 2010;13(3):127–137. doi: 10.1007/s12892-010-0064-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesari V, Krishnamachari A, Rangan L. Systematic characterisation and seed oil analysis in candidate plus trees of biodiesel plant, Pongamia pinnata. Ann Appl Biol. 2008;152:397–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2008.00231.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesari V, Sudarshan M, Das A, Rangan L. PCR amplification of the genomic DNA from the seeds of Ceylon ironwood, Jatropha, and Pongamia. Biomass Bioenergy. 2009;33:1724–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2009.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesari V, Das A, Rangan L. Physico-chemical characterization and antimicrobial activity from seed oil of Pongamia pinnata, a potential biofuel crop. Biomass Bioenerg. 2010;34(1):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2009.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kesari V, Madurai Sathyanarayana V, Parida A, Rangan L. Molecular marker-based characterization in candidate plus trees of Pongamia pinnata, a potential biodiesel legume. AoB Plants. 2010 doi: 10.1093/aobpla/plq017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar B, Kumar U, Yadav Hemant K. Identification of EST–SSRs and molecular diversity analysis in Mentha piperita. Crop J. 2015;3:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cj.2015.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mall RK, Gupta A, Singh R, Singh RS, Rathore LS. Water resourcesand climate change: an Indian perspective. Curr Sci. 2006;90:1610–1626. [Google Scholar]

- McConn M, Browse J. The critical requirement for linolenic acid is pollen development, not photosynthesis, in an Arabidopsis mutant. Plant Cell. 1996;8:403–416. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.3.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Met Office (2011) Climate: Observations, projections and impacts-India. Hadley Center, UK Met Office: Exeter, UK

- Metz J, Ribbers K, Tielborger K, Muller C. Long- and medium-term effects of aridity on the chemical defense of a widespread Brassicaceae in the Mediterranean. Environ Exp Bot. 2014;105:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riar DS, Rustgi S, Burke IC, Gill KS, Yenish JP. EST-SSR development from 5 lactuca species and their use in studying genetic diversity among L. serriola Biotypes. J Hered. 2011;102:17–28. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esq103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savadi SB, Fakrudin B, Nadaf HL, Gowda MVC. Transferability of sorghum genic microsatellite markers to peanut. Am J Plant Sci. 2012;3:4. doi: 10.4236/ajps.2012.39142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelke RG, Rangan L. Isolation and characterisation of Ty1-copia retrotransposons from Pongamia pinnata. Trees. 2019 doi: 10.1007/s00468-019-01878-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sneath PHA, Sokal RR. Numerical taxonomy: the principles and pratice of numerical classification. San Francisco: Freeman; 1973. p. 573. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkheh K, Prudencio AS, Ghebinejad A, Dehkordi MK, Erogul D, Rubio M, Martinez-Gomez P. In silico search, characterization and validation of new EST-SSR markers in the genus Prunus. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:336. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2143-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreeharsha RV, Mudalkar S, Singha KT, Reddy AR. Unravelling molecular mechanisms from floral initiation to lipid biosynthesis in a promising biofuel tree species, Pongamia pinnata using transcriptome analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34315. doi: 10.1038/srep34315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney R, Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth G, Gaspari Z, Jurka J. Microsatellites in different eukaryotic genomes: survey and analysis. Genome Res. 2000;10:967–981. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ul Haq S, Kumar P, Singh RK, Verma KS, Bhatt R, Sharma M, Kachhwaha S, Kothari SL. Assessment of functional EST-SSR markers (sugarcane) in cross-species transferability, genetic diversity among poaceae plants, and bulk segregation analysis. Genet Res Int. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/7052323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Yu G, Shi B, Wang X, Qiang H, Gao H. Development and characterization of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers based on rna-sequencing of Medicago sativa and in silico mapping onto the M. truncatula genome. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner K, Ranger N, Surminski S, Arnold M, Linnnerooth-Bayer J, Michel-Kerjan E, Kovacs P, Herweijer C (2009) Adaptation to climate change: linking disaster risk reduction and insurance. United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction Secretariat (UNISDR): Geneva, Switzerland. 18

- Yadav HK, Alok R, Asif MH, Shrikant M, Sawant SV, Rakesh T. EST-derived SSR markers in Jatropha curcas L.: development, characterization, polymorphism, and transferability across the species/genera. Tree Genet Genomes. 2011;7:207–219. doi: 10.1007/s11295-010-0326-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi T, Shiono K, Nagano M, Fukazawa A, Ando M, Takamure I, Mori H, Nishizawa NK, Kawai-Yamada M, Tsutsumi N, Kato K, Nakazono M. Ethylene biosynthesis is promoted by very-long-chain fatty acids during Lysigenous aerenchyma formation in rice roots. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:180–193. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Wu F, Luo K, Zhao Y, Yan Q, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Zhang J. Cross-species transferability of EST-SSR markers developed from the transcriptome of Melilotus and their application to population genetics research. Sci Rep. 2017;7:17959. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Wu Z, Tang D, Lv C, Luo K, Zhao Y, Liu X, Huang Y, Wang J. Development and identification of SSR markers associated with starch properties and N2-carotene content in the storage root of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:223. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Tian B, Zhang F, Tao F, Li W. Plant adaptation to frequent alterations between high and low temperatures: remodelling of membrane lipids and maintenanceof unsaturation levels. Plant, Cell Environ. 2011;34(9):1431–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Song P, Koo DH, Guo L, Li Y, Sun S, Weng Y, Yang L. Genome wide characterization of simple sequence repeats in watermelon genome and their application in comparative mapping and genetic diversity analysis. BMC Genom. 2016;17:557. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2870-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.