Loneliness is becoming increasingly recognized as a threat to mental health [1]. Social isolation during childhood is particularly detrimental to the normal functioning of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the establishment of adult social behavior. In mice, juvenile social isolation (jSI) following weaning for 2 weeks, but not during a later period, leads to decreased sociability in adult male mice, suggesting a juvenile sensitive period for establishing adult sociability [2, 3]. Identifying a specific mPFC social circuit vulnerable to childhood isolation will likely point toward therapeutic targets for the amelioration of social processing deficits shared across a range of psychiatric disorders [4].

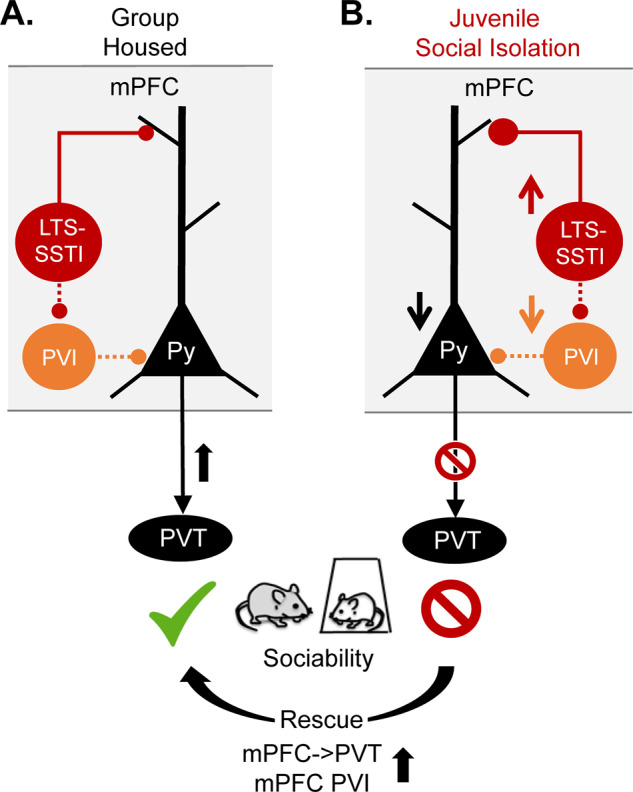

In our recent studies [3, 5], we identified specific sub-populations of mPFC excitatory and inhibitory neurons that are required for normal sociability and profoundly vulnerable to jSI in mice (Fig. 1). Among excitatory pyramidal neurons, we found that mPFC neurons projecting to the posterior paraventricular thalamus (PVT), which relays signals to the classical reward circuitry, are activated during social exploration in adult group-housed mice, but not in jSI mice [5]. Chemogenetic or optogenetic suppression of mPFC→PVT activity is sufficient to induce sociability deficits in group-housed mice. jSI leads to both reduced excitability of mPFC→PVT neurons and increased inhibitory input drive in adulthood. In contrast, other mPFC neurons projecting to nucleus accumbens or contralateral mPFC show no deficits in jSI mice [5, 6], suggesting that mPFC→PVT neurons and the associated inhibitory neurons are particularly vulnerable to jSI.

Fig. 1. A vulnerable mPFC social circuit in response to juvenile social isolation in mice.

A. Activation of mPFC→PVT projection neurons (black) or mPFC PVIs (orange) is essential for normal sociability in adult group-housed mice. B. However, these neurons show decreased intrinsic excitability and an increased inhibitory input drive from mPFC LTS-SSTIs (red) in juvenile socially isolated (jSI) mice, which show decreased sociability in adulthood. Decreased sociability can be induced in normal animals by inhibiting mPFC→PVT projection/mPFC PVIs or activating mPFC LTS-SSTIs in adulthood. Sociability deficits of jSI mice can be rescued by increasing PFC→PVT projection neuron or mPFC-PVI activity (bottom arrow).

On inhibitory neurons’ side, we found that a specific subclass of deep-layer Somatostatin-expressing low-threshold spiking interneurons (LTS-SSTIs) showed increased excitability [5], likely contributing to an increased inhibitory drive onto mPFC→PVT neurons in jSI mice. In contrast, Parvalbumin-expressing interneurons (PVIs) show reduced intrinsic excitability and decreased synaptic drive [3] in a similar fashion to mPFC→PVT neurons in adult jSI mice. These divergent changes in mPFC interneurons seem to contribute to sociability deficits in jSI mice as chemogenetic suppression of mPFC PVIs or activation of LTS-SSTIs recapitulates sociability deficits caused by jSI [3, 5]. To our surprise, these deficits are not observed immediately after the isolation period but only later, in adulthood. This suggests that the observed social deficits may be caused not by lack of social experience per se, but by adaptations to living in isolation that prevent mice from adapting to group living following re-housing. The juvenile window may be a sensitive period for behavioral plasticity, and once closed, mice may not be able to adjust their social strategy.

Our studies also demonstrated that the identified vulnerable mPFC social circuit is a promising target for treatments of social behavior deficits. Through stimulation of mPFC→PVT neurons [5] or mPFC PVIs in adulthood [3], we are able to rescue the sociability deficits caused by jSI. Given that previous genetic and transcriptomic studies show that many risk genes for autism and schizophrenia are highly expressed in the identified vulnerable social circuit, future studies are warranted to investigate the extent to which disease risk genes impact maturation of the identified circuit, and the effect of targeting the circuit for treating social processing deficits relevant to psychiatric disorders.

Funding and disclosure

This work was supported by NIH R01MH118297, R01MH119523, and the Simons Foundation/SFARI (610850). The author acknowledges the co-authors on the original papers L.K. Bicks, S. Akabarian, K. Yamamuro, and M. Leventhal. The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pitman A, Mann F, Johnson S. Advancing our understanding of loneliness and mental health problems in young people. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:955–6. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30436-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Makinodan M, Rosen KM, Ito S, Corfas G. A critical period for social experience-dependent oligodendrocyte maturation and myelination. Science. 2012;337:1357–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1220845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bicks LK, et al. Prefrontal parvalbumin interneurons require juvenile social experience to establish adult social behavior. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1003. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14740-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bicks LK, Koike H, Akbarian S, Morishita H. Prefrontal cortex and social cognition in mouse and man. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1805. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamuro K, et al. A prefrontal–paraventricular thalamus circuit requires juvenile social experience to regulate adult sociability in mice. Nat Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41593-41020-40695-41596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamuro K, et al. Social isolation during the critical period reduces synaptic and intrinsic excitability of a subtype of pyramidal cell in mouse prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2018;28:998–1010. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhx010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]