Abstract

Introduction

Face-touching behaviour often happens frequently and automatically, and poses potential risk for spreading infectious disease. Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have shown its efficacy in the treatment of behaviour disorders. This study aims to evaluate an online mindfulness-based brief intervention skill named ‘STOP (Stop, Take a Breath, Observe, Proceed) touching your face’ in reducing face-touching behaviour.

Methods and analysis

This will be an online-based, randomised, controlled, trial. We will recruit 1000 participants, and will randomise and allocate participants 1:1 to the ‘STOP touching your face’ (both 750-word text and 5 min audio description by online) intervention group (n=500) and the wait-list control group (n=500). All participants will be asked to monitor and record their face-touching behaviour during a 60 min period before and after the intervention. Primary outcome will be the efficacy of short-term mindfulness-based ‘STOP touching your face’ intervention for reducing the frequency of face-touching. The secondary outcomes will be percentage of participants touching their faces; the correlation between the psychological traits of mindfulness and face-touching behaviour; and the differences of face-touching behaviour between left-handers and right-handers. Analysis of covariance, regression analysis, χ2 test, t-test, Pearson’s correlations will be applied in data analysis. We will recruit 1000 participants from April to July 2020 or until the recruitment process is complete. The follow-up will be completed in July 2020. We expect all trial results to be available by the end of July 2020.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, an affiliate of Zhejiang University, Medical College (No. 20200401-32). Study results will be disseminated via social media and peer-reviewed publications.

Trial registration number

Keywords: education & training (see medical education & training), mental health, public health, health & safety

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the efficacy of brief mindfulness intervention to reduce face-touching behaviour.

This is a theoretical framework guided (mindfulness-based cognitive behaviour theory) large sample size RCT to evaluate the efficacy of ‘STOP (Stop, Take a Breath, Observe, Proceed) touching your face’ during the outbreak of COVID-19.

‘STOP touching your face’ programme is a free, brief, simple and widely accessible mindfulness-based behaviour change intervention.

There is no digital videotape recording for the behaviour of face-touching by researchers. Alternatively, it will be self-monitored.

This is only a brief intervention by internet. A face to face long-term mindfulness intervention will help participants gain the maximum benefits of practice.

Introduction

Non-verbal behaviour plays an important role in interpersonal relations and constitutes a large amount of all communication. But self-touching is usually not used to communicate with others and is often done automatically without thinking about it at all in our daily life.1 It might be one of the so called ‘autistic’ gestures when they have no evident meaning.2 Spontaneous facial self-touching or face-touching has been defined as the use of the hand to touch the individual’s own face to scratch, rub, groom or caress it. Research shows that the average face-touching frequency ranges from approximately 163 –234 times per hour. Furthermore, research of face-touching across handedness showed that left-handed individuals more frequently touch their face than their counterparts.5

An increase in face-touching frequency may result in increased risk of transmissible infections, defined as self-inoculation or auto-inoculation (a type of contact transmission occurs when a person transfers an infectious disease from one part of the body to another, eg, when a contaminated hand makes subsequent contact with the nose and introduces contaminated material to those areas).3 4 Of all face-touching behaviours, touching the T-zones will pose a potential risk for transmission and acquisition of a range of infectious diseases. Unfortunately, research found that 42.2%6–44%4 of face-touching involved in contacting with a mucous membrane. Even clinicians touch their T-zones (the mucus membranes of the eyes, nose and mouth) as frequently as 19 times on average within 2 hours.7 Many diseases can be spread by self-inoculation in this way, including COVID-19.8 9 Thus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the WHO have been telling people to stop touching their faces.

However, even we all know that stop touching our faces will minimise spread of COVID-19 and other germs. The question is how to stop this behaviour? Although face-touching is often an automatic behaviour without conscious thought or decision, research indicates that the frequency of self-touching and the duration of touch and contact are associated with cognitive and emotional demands.10 11 In addition to emotional states, especially negative affect states, self-touching also has been linked to information processing and production.12

Raising self-awareness of face-touching behaviour may be effective in reducing or avoiding this behaviour. For example, every time when you touch your face, be mindful, notice how you touched your face, check what you are thinking, physical and psychological feeling or your sensation that preceded it. This process or skill is similar to ‘mindfulness practice’ developed by Kabat Zinn.13 Mindfulness can be defined as ‘Mindful Awareness is the moment-by-moment process of actively and openly observing one’s physical, mental and emotional experiences’ (Mindful Awareness Research Center at the University of California at Los Angeles). Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are proven to be clinically efficacious in treatment of behavioural disorders, such as alcohol drinking, smoking, gambling,14–16 attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder,17 eating disorders,18 19 as well as in enhancing the emotional health of Chinese long-term male prison inmates.20 Increasing peoples’ awareness of their habituated face-touching behaviour may help individuals to avoid touching their face by contaminated hands, and decrease the risk of spreading infectious diseases. The structured MBIs, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) programme, are 8–10 weeks course,21–24 but brief MBIs can also produce numerous health-related outcomes, even only with one session intervention and as brief as 5 min.25 26 Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of a brief MBI further suggested the feasibility and effectiveness of short- term, self-guided, internet or smartphone-based interventions.27 28

The primary objective of this proposed project is to identify a simple but effective practice to reduce or avoid face-touching to low people’s chances of catching infectious diseases like COVID-19. Based on the efficacy of MBIs in treatment of some behavioural disorders and the efficacy of short-term MBIs, we here propose a RCT of an online mindfulness-based brief intervention skill named ‘STOP (Stop, Take a Breath, Observe, Proceed) touching your face’. It is hypothesised that this skill will be an effective, feasible, accessible skill in reducing or avoiding face-touching for people in the general population. To be specific, the primary hypothesis of this brief behavioural intervention is that, compared with a control intervention, the intervention would result in greater reduction of face-touching behaviour. We also hypothesise that the frequency of face-touching behaviour will also be reduced. Based on the theory that both face-touching behaviour and mindfulness link to cognitive or emotional process,10 23 we hypothesise that people with higher levels of self-reported mindfulness will touch their face less frequently. Given left-handed individuals more frequently touch their face than their counterparts.5 It is hypothesised that, compared with right-handed participants, left-handed individuals will touch their face more frequently during their 60 min self-monitoring of face-touching.

Methods and analysis

Patient and public involvement

Neither participants nor the public were involved in the design, recruitment or conduct of the study.

Study design and participants

In this online-based, randomised, parallel-group trial, undertaken in China by internet, about 1000 participants willing to participate in ‘STOP touching your face’ training programme and provide electronic consent (e-consent), will be randomly allocated to mindfulness-based ‘STOP touching your face’ intervention group or a control group at a 1:1 ratio. A 2×2 (practice group and control group×premeasurements–postmeasurements) experimental design will be used. Since participants will be told that they will either receive ‘STOP touching your face’ training programme before (intervention group) or after (control group) the second 60 min self-monitoring face-touching behaviour, blinding of participants will not be possible. Blinding of the investigators (mainly YLiao and LW) who are directly involved in interventions will also not be possible because of the nature differences of these two interventions (‘STOP touching your face’ training programme intervention and control intervention). The investigators (JT and YLiu) who will assess the outcomes will be blinded to participants’ allocated groups until all data have been analysed. All participants who are allocated to the control group will have the opportunity to practice this skill after the end of the study period. An overview of participant eligibility criteria is given in box 1.

Box 1. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria:

18 years of age or older.

Being able to access online services.

Being able to read and write in Chinese.

Expressing an interest in participant this study.

Willing to provide informed consent to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria:

Under 18 years of age.

Unable to access online services.

Unable to read and write in Chinese.

Already received ‘not to touch your face’ training.

Sample size and power calculation

This study aims to recruit 1000 participants, with 500 in each group. The sample size assessment and power calculations are mainly on the basis of the results of RCTs of different types of online short-term mindfulness intervention for behavioural changes, such as for alcohol consumption16 and stopping smoking or decreasing smoking craving,29 or for positive psychological changes, such as enhancing well-being28 and reducing perceived stress and anxiety/depression symptoms.27 A single brief session of mindfulness of 11 min (n=34) detected a significant reduction in alcohol consumption compared with a relaxation control intervention (n=34).16 It is estimated that, for assessing stop face-touching behaviour, individuals who received mindfulness intervention will at least twice likely to reduce the chance of touching T-Zone than the control group (5%–10% vs 2%–4%). Thus, a total of 562 participants (281 participants in each group) are required to achieve 80% power (1-beta=0.8), as significant at the 5% level (alpha=0.05), an increase in the outcome measure from 4% in the control group to 10% in the intervention group. However, online interventions often have much higher dropout rate than face to face intervention. A web-based guided self-help intervention for preventing depression reported about 20% dropout rate at 6-month follow-up,30 but a brief online MBI for reducing stress, anxiety and depression reported 30% dropout rate in the intervention group and more than a half in the waiting list control group.27 Considering the high loss to follow-up rate, this study will have a final target sample size of 1000 participants (500 in each arm), which will have sufficient power to detect a significant difference for the outcomes.

Recruitment

As in other similar research, we will advertise this programme online using social media (such as WeChat and QQ) to recruit potential participants. Potential participants will register their interest by sending messages by social media, email or sending text messages, or making a call to research assistants (by YW and ZW). Then, research assistants will contact respondents to assess their eligibility and explain the study to each participant and inform them that they would be allocated to either a control group or to a group that receives the mindfulness-based ‘STOP touching your face’ programme. Before collecting baseline data, electronically informed consent will be obtained from each participant. Participants who enrolled in this study could withdraw at any time. They will also be asked to provide contact information (will not be shared with any third party), in case any problems arise.

Baseline data

Prior to randomisation, demographic information and self-reported questionnaires will be obtained from all participants at baseline (assessed by YLiao, CP and QL). The demographic information of participants will be gender, age, years of education, marital status, occupation by the International Standard Classification of Occupations, living in rural or urban region, smoker types (non-smoker or current smoker and former smoker). The Five Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) will be applied to measure the dispositional tendency to be mindful in daily life. The Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI) will be used to assess handedness. Frequency of face-touching will be assessed at baseline and after intervention.

Randomisation and group allocation

After reporting the first 60 min self-monitoring face-touching behaviour, participants will be randomised and assigned (by YLiu) to either start the intervention immediately (intervention condition) or to a wait-list control condition (who will be offered the intervention immediately after reporting the second 60 min self-monitoring face-touching behaviour). Randomisation will be run by randomizeR (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=randomizeR). All participants will report the first self-monitoring by the same link (the same Excel file will be downloaded), and the second will be reported by two different links (two separated Excel files will be downloaded) to detect group allocation. Group allocation will not be concealed to investigators who will provide interventions. But the investigators (by JT and YLiu) who will analyse the data for evaluating outcomes will be blinded to participants’ treatment allocations until the entire analysis has been completed.

Development of ‘STOP touching your face’ training programme

Theory

Face-touching behaviour is often an automatic behaviour that could potentially disseminate respiratory infections (eg, influenza, COVID-19), yet can be changed. However, changing the behaviour of face-touching is ‘easier said than done’, as there is only limited evidence for the neuropsychological basis or physiological fundamentals of this behaviour. Research shows that the frequency of self-touching increases when attention is distracted,10 as well as under stressful situations or with negative affect.11 Cognitive behavioural theory-based mindfulness intervention (MBCT24) has been used as a psychological intervention for people with mental or behaviour problems, targeting both cognitive and behavioural problems. MBIs13 can help people cultivate positive affect, increase self-awareness and concentration that are associated with reducing frequency of face-touching.

Practice

STOP31 is an acronym that stands for four action: ‘Stop’, ‘Take a breath’, ‘Observe’, ‘Proceed’. It is a helpful aid in becoming more mindful of our body, behaviour and emotion on a daily basis. The following is the instruction for how to practice STOP:

S=stop

Remind yourself to STOP. Whatever you are doing in this moment (eg, touching your month, pinching your nose, rubbing your eyes, resting your chin on your hands), pause for a minute.

T=take

Take a deep breath. This reconnects you with your body. Pay attention to your breathing and just allow yourself to continue to breathe normally and naturally.

O=observe

Observe what is happening for you in this moment—including thoughts, feelings and emotions (eg, feel distracted, anxious or nervous?). What do you notice in your body (eg, feel itchy or tingling on any part of your face)? You can be aware of anything: posture, sensations, tension in your body, or, once again, your breath. You might notice the sound around you. You might even notice your thoughts or emotions.

P=proceed

Proceed with whatever you were doing before you came to a STOP or something that you want to do in the moment (eg, proceed with touching your face, or stop face-touching and take an alternative behaviour).

The STOP practice is very short, simple, and the acronym (STOP) makes it easy to remember as well. Thus, it has become one of the most popular mindfulness-based practices. The practice of STOP may cultivate a space between stimulus and response, which could help avoid the mostly spontaneous behaviour of facial self-touching. The STOP practice in Chinese was already developed by YLiao, QL and CP. YLiao developed the ‘STOP touching your face’ training programme. Both 750-word text and 5 min audio description (see online supplemental file 1) will be available by online.

bmjopen-2020-041364supp001.mp3 (9.6MB, mp3)

Procedures

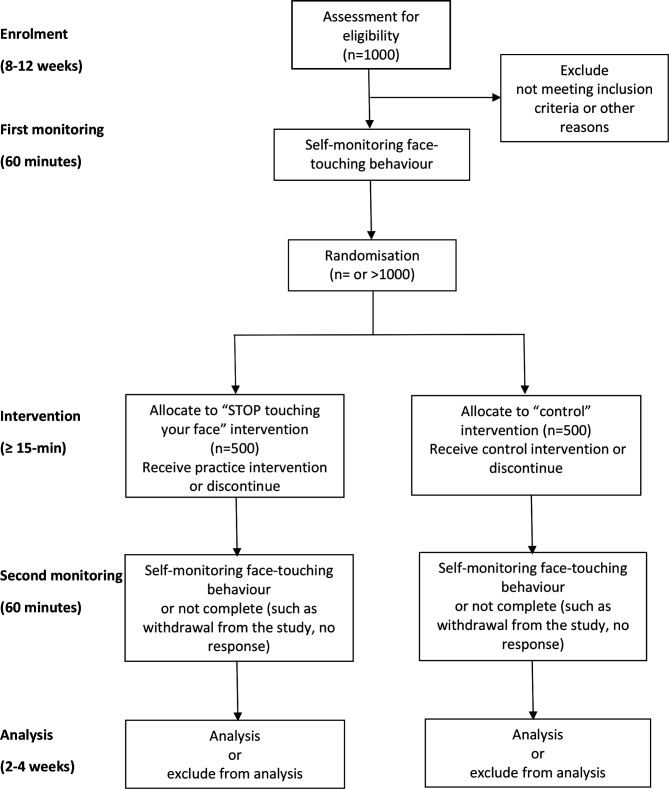

After advertising, participants who are interested in this study will be assessed for eligibility by making a call or communicating with social media (mainly WeChat). Then, eligible participants will sign a e-consent form (online supplemental file 2), and complete baseline information and the first self-monitoring of frequency of face-touching in a 60 min period by online. Afterwards, participants will receive a brief mindfulness-based ‘STOP touching your face’ intervention or control intervention. For both groups, the second self-monitoring of frequency of face-touching behaviour will be taken at least 1 hour apart from the first one. The schedule of study procedures summarises in figure 1. The details of the procedure will include the following three steps:

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram. Participants from the ‘control’ intervention will receive ‘STOP (Stop, Take a Breath, Observe, Proceed) touching your face’ intervention (both text and audio description) immediately after completing the second self-monitoring face-touching behaviour. But they will not be required to practice it or to practice it at least 15 min.

bmjopen-2020-041364supp002.pdf (106.5KB, pdf)

Step 1: the first 60 min self-monitoring of face-touching behaviour (before intervention)

In order to measure the changes of face-touching behaviour before and after intervention, all eligible participants will receive the instruction (in Chinese) of how to self-monitored and reported the frequency of face-touching in any of the mucosal area (eyes, nose, mouth) and non-mucosal area (ears, cheeks, chin, neck, forehead, hair) during a 60 min period. All participants will be required to monitor their face-touching behaviour during a 60 min period, and be encouraged to do it in a manageable situation. Wearing facial mask will not be permitted during the time of self-monitoring face-touching. All participants will be provided with the same link to complete their baseline information and the first 60 min self-monitoring of face-touching behaviour, and be encouraged to complete this questionnaire immediately after completion of self-monitoring.

Instruction: ‘(1) Please find a convenient time, no need to deliberately change your routine life (such as working or studying at the desk, watching TV), observe and record how many times you touched your hair, forehead, eyes, nose, mouth, ears, cheeks, Chin and neck in 1 hour period (if you touched your mouth and nose at one time, you should count one time for month-touching and one time for nose-touching). If there is any information that you cannot understand, please contact with me at any time; (2) fill in the following content immediately after completion of self-monitoring (with a link to “hand-to-face contacts” behaviour monitoring record 1); (3) please contact with me to send the information about intervention to you when you completed the link; (4) you will repeat another 1 hour period self-monitoring after your receiving another information (either “STOP touching your face” programme or just thanks words).’

Step 2: Intervention

Intervention group

Participants from the intervention group will receive the online mindfulness-based ‘STOP touching your face’ programme (both 750-word text and 5 min audio description). Each participant will be required to read the text of the programme first and then listen to the audio. They will be encouraged to practice this technique until they feel confident and natural. The systematic review showed the efficacy of single session of brief MBIs, the average length of which was 15 min, ranged from less than 5 to 25 min.25 Thus, the requirement practice time will be at least 15 min (excluding the time of reading the text and the first time of listening to the audio). This online MBI will not have face-to-face interaction between the experimenter and participants throughout the entire study.

Control group

Participants who allocate to the control group will only receive information to thank them and encourage them to complete the study. They will be reminded to receive ‘STOP touching your face’ programme after the end of this study.

Both groups

Participants from both groups will be reminded to contact with us to provide the instruction of another self-monitoring behaviour of face-touching.

Step 3: the second 60 min self-monitoring of face-touching behaviour (after intervention)

After intervention, all participants will be required to monitor their face-touching behaviour during a 60 min period again. When participants tell us ‘I am ready to do another self-monitoring’, they will receive instruction of how to complete the second 60 min self-monitoring of face-touching behaviour during a 60 min period. The repeat measurement of the face-touching behaviour will be done at least 1 hour apart from the first self-monitoring. All participants will be encouraged to monitor their face-touching behaviour in two similar situations.

Instruction: ‘(1) Again, please find a convenient time, no need to deliberately change your routine life (such as working or studying at the desk, watching TV), observe and record how many times you touched your hair, forehead, eyes, nose, mouth, ears, cheeks, chin and neck in 1 hour period (if you touched your mouth and nose at one time, you should count one time for month-touching and one time for nose-touching). It is better to find a similar situation (the similar time if not in the same day, same place, and when you are doing the same thing). You need to do it at least 1 hour apart from the last observation. If there is any information that you cannot understand, please contact with me at any time; (2) fill in the following content immediately after completing self-monitoring (with a link to “hand-to-face contacts” behaviour monitoring record 2, the two groups will receive different links); (3) please let me known when you completed the link (the intervention group); please contact with me to send the programme to you when you completed the link (the control group)’.

All participants will be thanked and encouraged to practice ‘STOP touching your face’ regularly after the end of the study. All outcomes will be collected by an online survey through the Chinese professional survey software WenJuanXing (Sojump, Shanghai, China, www.sojump.com). For non-responders, a reminding message will be sent to them by their provided contact information for reporting the outcomes.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The efficacy of short-term mindfulness-based ‘STOP touching your face’ intervention (≥15 min) for reducing face-touching behaviour, measuring by reduction of frequency of face touching behaviour (this will be calculated as the total times of face-touching (including the eyes, nose, mouth, ears, cheeks, chin, neck, forehead, hair) during a 60 min period before the intervention minus the total times of face-touching after the intervention).

Secondary outcomes

The reduction of percentage of participants touching their faces (this will be calculated as the percentage of participants touching their faces (including any of the following areas: the eyes, nose, mouth, ears, cheeks, chin, neck, forehead, hair) during a 60 min period before the intervention—the percentage of participants touching their faces after the intervention) after intervention; the factors (demographic characteristics, psychological traits of mindfulness) that would be associated with reduction of frequency of face-touching; the differences of face-touching behaviour between left-handers and right-handers.

Measures

Frequency of face-touching

Self-observation or self-monitoring of face-touching behaviour will be required to report from each participant. A standardised scoring sheet will be provided to tally the frequency of hand-to-face contacts, the touched area of the face, including the mucosal area (eyes, nose, mouth) and non-mucosal area (ears, cheeks, chin, neck, forehead, hair), and the time in seconds of each contact will be recorded in a 60 min period.4

Percentage of participants touching their faces

This will be the number of participants who touched any of the following areas: the eyes, nose, mouth, ears, cheeks, chin, neck, forehead, hair, during their 60 min self-monitoring of face-touching/the total number of participants in the intervention group or the control group.

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire32–34

This self-report scale is currently the most frequently used mindfulness questionnaire to measure changes in participant’s tendency to be mindful in daily life by the following five related facets: observing (noticing, attending to sensations, perceptions, thoughts, feelings; eight items), describing (labelling feelings, thoughts with words), acting with awareness (automatic pilot, concentration, non-distraction), non-judging internal experience and non-reactivity to internal experience. Participants will be asked to what extent each of the statements are true of them. Each item is on a 1–5 Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). The scores represent a spectrum of mindfulness with no cut-off points, higher scores indicate higher levels of mindfulness. The factor structure of the short version (FFMQ-15) will be used in this study, which has been consistent with that of the FFMQ-39.35

Edinburgh Handedness Inventory36 37

EHI is the most widely used 10-item self-report inventory to assess handedness. It is comprised the following 10 activities: (1) writing, (2) drawing, (3) throwing, (4) using scissors, (5) a toothbrush (6) knife (without fork), (7) spoon, and such activities involving both hands as (8) using a broom (upper hand), (9) striking a match and (10) unscrewing the lid of a bottle. To complete the EHI, one or two check marks are placed under ‘left (L)’ or ‘right (R)’ columns, indicating strength of preference for each activity. Participants will be asked write ‘2’, ‘1’ or ‘0’ in the appropriate corresponding column. If the preference is very strong that they would never try to use the other hand unless absolutely forced to, then they will mark this column as “2” and the other column as ‘0’. If they are really indifferent, they will mark it as ‘1’ in both columns. A laterality quotient (LQ=R−L/R+L×100) can be calculated, where a score of 100 reflects complete right-handedness, and a score of −100 reflects complete left-handedness.

Withdrawal from the programme

Every participant will feel free to withdraw from the study at any time and without giving any reason. On the basis of the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle,38 participants who fail to respond to the second assessment will be retained in the analysis according to the arm they were randomised to, irrespective of whether they did the intervention or not. Only participants who request withdrawal from the study will be excluded from the analysis, and reasons for withdrawal will be noted if they are available. However, self-monitoring itself may increase the awareness of face-touching behaviour, then consequently increase or decrease the frequency of face-touching behaviour in the second time of observation. Alternatively, a complete case analysis will also be performed in which any participant withdrew from the study in the second observation will be excluded.

Data collection

Data will be collected on line by WenJuanXing, a Chinese online market research Web site that provides professional online questionnaire survey or data collection for RCTs.39 Data will be monitored by data monitoring committee of the hospital. Personal data will be de-identified.

Data analysis

All data will be automatically collected by internet. A user-specified Excel file will be downloaded from the database. There will be no interim analyses. When all data have been obtained, they will be analysed and blinded to intervention assignment by the trial statistician using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.r-project.org/) and SPSS (IBM Corp, released 2013, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.22.0. Armonk, New York). Descriptive statistics will be applied for demographic and face-touching‐related characteristics at baseline; two sample t-test or Mann-Whitney U test (for continuous variables) and χ2 test (for categorical variables) will be applied to compare the demographic information and face-touching behaviour at baseline between the STOP intervention group and control group. Percentage of touching the T-Zone participants between preintervention and postintervention in the STOP group and the control group will be compared by χ2 test. For assessing the primary outcome, determining if the ‘STOP touching your face’ intervention group showed a reduction of face-touching behaviour than the control group, two sample t-test or Mann-Whitney U test will first be applied to compared group differences in reduction of the frequency of face-touching. Then, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) will be applied with controlling for demographic information (such age, handedness and prior mindfulness meditation experience). In ANCOVA model, the dependent variable will be the reduction of face-touching behaviour. The preintervention measure of the total times of face-touching will be controlled as a covariate, and intervention will be a fix factor. This model will assess the differences in the postintervention means after accounting for preintervention values. Pearson’s correlations or regression analysis (linear and binary regression model) will be used to explore the any factor that associated with face-touching behaviour at baseline and reduction of face-touching behaviour in the intervention group and in the control group. ITT basis will be applied in this study, all participants who complete the first 60 min self-monitoring face-touching behaviour will be retained in the analysis. The last-observation-carried-forward method will be applied to handle incomplete or missing data (assuming for no reduction of the frequency of face-touching). In addition, a complete case analysis will be performed in which any participant with missing information on the follow-up will be excluded. All tests will be two-tailed. A two-sided p<0.05 will be used to determine statistical significance.

Safety

Throughout the ‘STOP touching your face’ programme, participants will be encouraged to communicate with us if they experience any mindfulness practice relative issues. Adverse events will be monitored during the study. The MBIs are regarded as relatively safe interventions.40 Research showed that even highly vulnerable participants (such as patients with major depressive disorder41) can safely practice mindfulness, but if participants experience any health-related issues, they will be encouraged to contact with us, or we will refer a healthcare provider. This study is not clinical-facilitated and may have very low risk of any safety issue. We will send a message to each participant to check whether they have any safety issues after providing them with intervention instruction.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by The Ethics Committee of Sir Run Run Shaw hospital, an affiliate of Zhejiang University, Medical College (No. 20200401-32). All activities associated with this protocol will be conducted in full compliance with the approved policies and procedures. Electronically Informed consent (this e-consent is a form of written consent) will be communicated and obtained from each participant prior to participation. All participant will be explained about the purpose, procedures and assessments, potential risks and benefits of the trial before recruitment. After fully understanding the study, participants will be informed that their participation in this research study is total voluntary. They can choose to (sign the electronic consent form by selecting ‘agree to participant’) or not to participate (sign the electronic consent form by selecting ‘disagree to participant’). Participation can withdrawal at any time without reasons. Contact information (phone number and social media contact like WeChat contact ID) of the study coordinator for any future questions and concerns will be provided and informed to each participant. We will recruit 1000 participants from April to July 2020 or until the recruitment process is complete. The follow-up will be completed in July 2020. We expect all trial results to be available by the end of July 2020. Any results from this trial (publications, conference presentations) will be disseminated via social media and be published in peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings.

Discussion

This RCT is to investigate the efficacy of brief MBI of ‘STOP touching your face’ for people from general population in China. To our knowledge, this will be the first RCT to evaluate the efficacy of brief mindfulness intervention to reduce face-touching behaviour on the basis of mindfulness and cognitive behavioural principles.

The strength of this study is that this is a theoretical framework guided (mindfulness-based cognitive behaviour theory) large sample size RCT to evaluate the efficacy of ‘STOP touching your face’ during the outbreak of COVID-19. If ‘STOP touching your face’ programme is proved to be effective, it opens up its potential application worldwide at the population level. As ‘STOP touching your face’ programme is a free, brief, simple and widely accessible mindfulness-based behaviour change intervention, the public health impact of its expansion world-wide could be enormous, helping us to manage any face-touching spread infectious diseases, like COVID-19.

There are some limitations in this study. First, there is no digital videotape recording for the behaviour of face-touching by researchers. Alternatively, it will be self-monitored. Self-monitoring of physical (such as blood pressure), and mental health (such as anger or frustration that comes from daily life) has been used as a strategy for improving the treatment of a number of chronic conditions or reducing unhealth behaviours including smoking, drinking, gambling and so on.42 Thus, self-monitoring itself may change participants face-touching behaviour by creating a more active role in observing this behaviour. Also, self-reported results of self-monitored times of face touching may be overestimated or underestimated. Furthermore, self-monitoring itself may increase the awareness of face-touching behaviour, then consequently increase or decrease the frequency of face-touching behaviour in the second time of observation. The results will be more accurate under lab conditions. In order to reduce the bias, we will invite a subgroup of participants with video record by another person to confirm the consistency of these results. Second, this is only an online intervention, participants may be more likely to drop out from the study. Thus, we will encourage participants contact with us if they have any questions or concerns. We will also apply an ITT principle to prevent potential bias caused by missing data from loss to follow-up, as well as a complete case analysis. Third, this is only a brief intervention by internet. A face to face long-term mindfulness intervention will help participants gain the maximum benefits of practice. However, neuroimaging study demonstrates that both long and short-term mindfulness practice can improve automatic emotion regulation,43 and RCT shows that brief online MBI can also increase mindfulness and decrease perceived stress and symptoms of anxiety or depression.27 Fourth, this is a MBI, and mindfulness could make participants better at catching themselves touching their faces, so participants from the intervention group may report higher frequency than the control group in the second 60 min self-monitoring of face-touching behaviour. Finally, we submitted this protocol to the journal during the time of recruiting.

In conclusion, this is the first RCT to evaluate the efficacy of brief mindfulness intervention to reduce face-touching behaviour. If ‘STOP touching your face’, a brief and simple skill, is proven effective, the public health impact of its expansion world-wide could be enormous, its dissemination will help us to manage any face-touching spread infectious diseases, like COVID-19.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

YLiao would like to thank Professor Ann McNeill from KCL for her suggestions and thank 5P Medicine (5P Yixue APP) for providing STOP audio description (see supplementary file). YLiao, CP and QL would like to thank the UCLA (the University of California at Los Angeles) Mindful Awareness Research CenterCentre for providing opportunities to them to learn and practice mindfulness.

Footnotes

Contributors: YLiao and JT developed and designed the study. YLiao, CP and QL developed STOP Practice, YLiao developed the ‘STOP touching your face’ training programme. YLiao discussed with LW and WC on the planning and conduct of the study, and discussed with YLiu and JT on the acquisition of data and the planning of data analysis. YLiao, LW, TL, SW, ZW, JC, CP, YW, LX and JZ conducted the interventions. JT and YLiu conducted data analysis. YLiao took the lead in drafting the manuscript protocol with contributions by JT and JC. QL, XG and WC advised the study design, and coordinated study approval. All authors read and proposed critical comments, as well as approved the manuscript for publication.

Funding: The research is supported by Zhejiang University special scientific research fund for COVID-19 prevention and control (2020XGZX046), the ‘Hundred Talents Programme’ funding from Zhejiang University, and the K.C. Wong Postdoctoral Fellowship to study at King’s College London (KCL). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to write the report or to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: YLiao developed the ‘STOP touching your face’ training programme.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Harrigan JA, Kues JR, Weber JG. Impressions of hand movements: Self-touching and gestures. Percept Mot Skills 1986;63:503–16. 10.2466/pms.1986.63.2.503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krout MH. Autistic gestures: an experimental study in symbolic movement. Psychol Monogr 1935;46:i–126. 10.1037/h0093363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicas M, Best D. A study quantifying the hand-to-face contact rate and its potential application to predicting respiratory tract infection. J Occup Environ Hyg 2008;5:347–52. 10.1080/15459620802003896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwok YLA, Gralton J, McLaws M-L. Face touching: a frequent habit that has implications for hand hygiene. Am J Infect Control 2015;43:112–4. 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimond S, Harries R. Face touching in monkeys, apes and man evolutionary origins and cerebral asymmetry. Neuropsychologia 1984;22:227–33. 10.1016/0028-3932(84)90065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Measurement of Face-touching frequency in a simulated train. E3s web of conferences; 2019. EDP sciences.

- 7.Elder NC, Sawyer W, Pallerla H, et al. Hand hygiene and face touching in family medicine offices: a Cincinnati area research and improvement group (caring) network study. J Am Board Fam Med 2014;27:339–46. 10.3122/jabfm.2014.03.130242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet 2020;395:497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.SWX O, Tan YK, Chia PY, et al. Air, surface environmental, and personal protective equipment contamination by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from a symptomatic patient. Jama 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller SM, Martin S, Grunwald M. Self-touch: contact durations and point of touch of spontaneous facial self-touches differ depending on cognitive and emotional load. PLoS One 2019;14:e0213677. 10.1371/journal.pone.0213677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunwald M, Weiss T, Mueller S, et al. Eeg changes caused by spontaneous facial self-touch may represent emotion regulating processes and working memory maintenance. Brain Res 2014;1557:111–26. 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrigan JA. Self-touching as an indicator of underlying affect and language processes. Soc Sci Med 1985;20:1161–8. 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90193-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabat‐Zinn J. Mindfulness‐based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical psychology: Science and practice 2003;10:144–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavicchioli M, Movalli M, Maffei C. The clinical efficacy of Mindfulness-Based treatments for alcohol and drugs use disorders: a meta-analytic review of randomized and nonrandomized controlled trials. Eur Addict Res 2018;24:137–62. 10.1159/000490762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sancho M, De Gracia M, Rodríguez RC, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of substance and behavioral addictions: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry 2018;9:95. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamboj SK, Irez D, Serfaty S, et al. Ultra-Brief mindfulness training reduces alcohol consumption in at-risk drinkers: a randomized double-blind active-controlled experiment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2017;20:936–47. 10.1093/ijnp/pyx064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haydicky J, Wiener J, Badali P, et al. Evaluation of a Mindfulness-based intervention for adolescents with learning disabilities and co-occurring ADHD and anxiety. Mindfulness 2012;3:151–64. 10.1007/s12671-012-0089-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kristeller JL, Wolever RQ. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: the conceptual Foundation. Eat Disord 2010;19:49–61. 10.1080/10640266.2011.533605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wanden-Berghe RG, Sanz-Valero J, Wanden-Berghe C. The application of mindfulness to eating disorders treatment: a systematic review. Eat Disord 2010;19:34–48. 10.1080/10640266.2011.533604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu W, Jia K, Liu X, et al. The effects of mindfulness training on emotional health in Chinese long-term male prison inmates. Mindfulness 2016;7:1044–51. 10.1007/s12671-016-0540-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shonin E, Van Gordon W, Griffiths MD. Mindfulness-based interventions: towards mindful clinical integration. Front Psychol 2013;4:194. 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med 2008;31:23–33. 10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2004;57:35–43. 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segal ZV, Teasdale J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. Guilford Publications, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howarth A, Smith JG, Perkins-Porras L, et al. Effects of brief Mindfulness-Based interventions on health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Mindfulness 2019;10:1957–68. 10.1007/s12671-019-01163-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Yang X, Wang L, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the effects of brief mindfulness meditation on anxiety symptoms and systolic blood pressure in Chinese nursing students. Nurse Educ Today 2013;33:1166–72. 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavanagh K, Strauss C, Cicconi F, et al. A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention. Behav Res Ther 2013;51:573–8. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howells A, Ivtzan I, Eiroa-Orosa FJ. Putting the ‘app’ in Happiness: A Randomised Controlled Trial of a Smartphone-Based Mindfulness Intervention to Enhance Wellbeing. J Happiness Stud 2016;17:163–85. 10.1007/s10902-014-9589-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garrison KA, Pal P, O'Malley SS, et al. Craving to quit: a randomized controlled trial of smartphone App-Based mindfulness training for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22:324–31. 10.1093/ntr/nty126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buntrock C, Ebert DD, Lehr D, et al. Effect of a web-based guided self-help intervention for prevention of major depression in adults with subthreshold depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016;315:1854–63. 10.1001/jama.2016.4326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smalley SL, Winston D. Fully present: the science, art, and practice of mindfulness. Da Capo Lifelong Books, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng Y-Q, Liu X-H, Rodriguez MA, et al. The five facet mindfulness questionnaire: psychometric properties of the Chinese version. Mindfulness 2011;2:123–8. 10.1007/s12671-011-0050-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Bruin EI, Topper M, Muskens JGAM, et al. Psychometric properties of the five facets mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ) in a meditating and a non-meditating sample. Assessment 2012;19:187–97. 10.1177/1073191112446654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, et al. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006;13:27–45. 10.1177/1073191105283504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gu J, Strauss C, Crane C, et al. Examining the factor structure of the 39-item and 15-item versions of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire before and after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people with recurrent depression. Psychol Assess 2016;28:791–802. 10.1037/pas0000263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang N, Waddington G, Adams R, et al. Translation, cultural adaption, and test–retest reliability of Chinese versions of the Edinburgh handedness inventory and Waterloo Footedness questionnaire. Laterality 2018;23:255–73. 10.1080/1357650X.2017.1357728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971;9:97–113. 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montori VM, Guyatt GH. Intention-To-Treat principle. CMAJ 2001;165:1339–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fitzpatrick T, Zhou K, Cheng Y, et al. A crowdsourced intervention to promote hepatitis B and C testing among men who have sex with men in China: study protocol for a nationwide online randomized controlled trial. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:489. 10.1186/s12879-018-3403-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong SYS, Chan JYC, Zhang D, et al. The safety of mindfulness-based interventions: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Mindfulness 2018;9:1344–57. 10.1007/s12671-018-0897-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piet J, Hougaard E. The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:1032–40. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JY, Wineinger NE, Steinhubl SR. The influence of wireless self-monitoring program on the relationship between patient activation and health behaviors, medication adherence, and blood pressure levels in hypertensive patients: a substudy of a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e116. 10.2196/jmir.5429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kral TRA, Schuyler BS, Mumford JA, et al. Impact of short- and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. Neuroimage 2018;181:301–13. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-041364supp001.mp3 (9.6MB, mp3)

bmjopen-2020-041364supp002.pdf (106.5KB, pdf)