Abstract

Objective

To investigate associations of morbidity with subsequent sickness absence (SA) and disability pension (DP) among initially nulliparous women with no, one or several childbirths during follow-up.

Design

Longitudinal register-based cohort study.

Setting

Sweden.

Participants

Nulliparous women, aged 18 to 39 years and living in Sweden on 31 December 2004 and the three preceding years (n=492 504).

Outcome measures

Annual mean DP and SA days (in SA spells >14 days) in the 3 years before and after inclusion date in 2005.

Methods

Women were categorised into three groups: no childbirth in 2005 nor during the follow-up, first childbirth in 2005 but not during follow-up, and having first childbirth in 2005 and at least one more during follow-up. Microdata were obtained for 3 years before and 3 years after inclusion regarding SA, DP, mortality and morbidity (ie, hospitalisation and specialised outpatient healthcare, also excluding healthcare for pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium). HRs and 95% CIs for SA and DP in year 2 and 3 after childbirth were estimated by Cox regression; excluding those on DP at inclusion.

Results

After controlling for study participants’ prior morbidity and sociodemographic characteristics, women with one childbirth had a lower risk of SA and DP than those who remained nulliparous, while women with more than one childbirth had the lowest DP risk. Morbidity after inclusion that was not related to pregnancy, childbirth or the puerperium was associated with a higher risk of future SA and DP, regardless of childbirth group. Furthermore, morbidity both before and after childbirth showed a strong association with SA and DP (HR range: 2.54 to 13.12).

Conclusion

We found a strong positive association between morbidity and both SA and DP among women, regardless of childbirth status. Those who gave birth had lower future SA and DP risk than those who did not.

Keywords: reproductive medicine, public health, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Since the study was based on nationwide population-based registers, all 492 504 women fulfilling our inclusion criteria could be included, not only a sample.

The large cohort allowed us to perform sub-group analyses and yielded high statistical precision.

The fact that the study was conducted in Sweden, a country characterised by high employment rate among women, limits health selection into paid work.

We could not include information on sickness absence spells shorter than 15 days.

Background

In societies with a high rate of female employment, women have on average a higher mean number of sickness absence (SA) days than men.1–4This gender difference in SA becomes more pronounced with the first pregnancy and childbirth.5–7 Several studies among women also show a temporary increase in the number of SA days during pregnancy.8–13 Other authors report that women living with children have higher SA than their counterparts not living with children.14 In contrast, when including also long-term SA, in terms of disability pension (DP), we found in some studies that except for the period before childbirth, women who give birth have lower mean SA/DP days per year than those who remain nulliparous, and that those having more than one childbirth have the lowest SA/DP levels 3 to 10 years after the childbirth.12 15 16

The increase in SA in relation to pregnancy and childbirth may have several explanations. During pregnancy and the puerperium, women experience profound endocrine, immune, metabolic and cardiovascular changes.17 18 The pregnancy-related immune changes increase susceptibility to infectious diseases and to more complicated courses in case of common infections. Immune changes affect also the activity of several autoimmune diseases, for example, in case of some disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, Graves disease and Hashimoto thyroiditis), there is an improvement during pregnancy and a worsening postpartum, while for others (such as systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis), there is an inverse manifestation.19 Pregnancy and the postpartum period are considered a ‘stress test of life’, that is, several diseases presenting first during this period may reveal the individual’s susceptibility to later disorders, for example, diabetes, psychiatric or cardiovascular diseases.18 20–23 Furthermore, the antenatal care and the screening for several disorders during pregnancy may increase women’s chance to be diagnosed during this period with pre-existing, undetected chronic conditions. A substantial proportion of women suffer from common pregnancy-related symptoms and disorders18 24 such as fatigue, headache, bowel problems, sleep-related problems, depression, urinary incontinence, back pain and pelvic pain,25–27 which may also contribute to SA during pregnancy.

Mass media, employers, policymakers and researchers have questioned whether the higher SA among women with children is indeed due to higher morbidity, or rather to individual choices related to wanting to stay home and handle domestic duties than to be in paid work.28 To the best of our knowledge, only one previous study investigated associations between morbidity and SA/DP among women giving and not giving birth. In a cohort of Swedish twin sisters (n=5118), they found a strong association between morbidity, measured in terms of hospitalisation, and the risk of SA and DP.29 To what extent findings from this selected and rather small group of twin sisters are generalisable to the total population is unclear. Also, it would be of interest to include wider information on morbidity than hospitalisation in such analyses. Most people with morbidity are not on SA or DP, and knowledge about the associations between morbidity and SA or DP is, in general, limited.1 28 30–34

Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate, in a nationwide population-based cohort, the associations of morbidity, assessed in terms of hospitalisation and specialised outpatient healthcare, with subsequent SA and DP among initially nulliparous women with no, one or several childbirths during follow-up.

Methods

This longitudinal population-based cohort study was based on nationwide register microdata, linked by the unique personal identity number assigned to all residents in Sweden.35 Anonymised data from the following six registers, kept by three authorities, were used:

From Statistics Sweden: The Longitudinal Integration Database for Health Insurance and Labour Market Studies36 for information on sociodemographics and year of migration.

From the National Board of Health and Welfare: (1) The Medical Birth Register to obtain information on date of deliveries and parity. It covers 97% to 99% of all births in Sweden since 1973; (2) The National In-Patient Register (established in 1964 and nationwide since 1987) for information on childbirths not included in the Medical Birth Register (date and diagnoses) and information on hospitalisations due to other causes (date and main and secondary diagnoses). If a delivery appeared in both registers, the information from the Medical Birth Register was used; (3) The National Out-Patient Register (established in 2001) for information on specialised outpatient healthcare (date and main diagnoses); (4) The Causes of Death Register for date of death.

From the Swedish Social Insurance Agency, for information from the Micro-data for Analyses of Social Insurance Register, on SA spells >14 days and on DP (dates and extent) for the period 2002 to 2008.

Study population

All women aged 18 to 39 years who had not given birth prior to 1 January 2005 and who lived in Sweden during the period 2002 to 2004 were included. The limits were based on the frequency distribution of age among primiparous women in Sweden; very few women had their first child before the age of 18 or after the age of 39 years. The lower age limit of 18 also means that all had at least a chance to have had SA before inclusion (not possible before the age of 16). Women in the extremes were analysed similarly to women of other ages. Study participants were categorised according to whether they gave birth in 2005 and during the follow-up for 3 years (Y+1 to Y+3), from date of delivery (T0). As the outcomes (SA and DP) might be influenced by a new pregnancy, all women were followed for an additional 43 weeks after end of Y+3.

The women were categorised into three groups, according to future childbirth:

B0: Women having no childbirth registered during follow-up (Y+1 to Y+3) nor during the subsequent 43 weeks.

B1: Women having their first childbirth in 2005 and no more births during follow-up (Y+1 to Y+3) or the subsequent 43 weeks.

B1+: Women having their first childbirth in 2005 and at least one more birth during follow-up (Y+1 to Y+3) or the subsequent 43 weeks.

Childbirth in the Patient Register was defined by main or secondary diagnoses according to the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10):37 O80-84 delivery, O75.7 vaginal delivery following previous caesarean section, O75.8 other specified complications of labour and delivery, and O75.9 complication of labour and delivery, unspecified.

For the women in B1 and B1+, the date of birth was used for T0, for the women in B0, T0 was set to 2 July 2005 (ie, the middle of the year). The final cohort included 492 504 women.

Morbidity

We measured morbidity in different ways. One was to calculate the mean number of hospitalisation days and of specialised outpatient visits (ie, morbidity requiring at least secondary healthcare) per year during the 3 years prior to and the 3 years after the date of T0. Another was the occurrence of any hospitalisation and/or specialised outpatient healthcare in the years before T0 (Y−3 to Y−1), in the year after T0 (Y+1), and in the 3 years after T0 (Y+1 to Y+3), respectively. All those measures were calculated for all such secondary healthcare, excluding visits due to screening for diseases, etc. (ICD-10 codes Z00-2 and Z10-13). The same measures were derived when having excluded such healthcare for diagnoses related to pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period (ICD-10: O00-O99 pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium, and Z30-Z39 health services in circumstances related to reproduction). For the exclusions, we used information on main diagnoses, that is, the diagnosis for which the patient was hospitalised or had specialised outpatient healthcare.

The Swedish sickness absence insurance system

All residents in Sweden aged 16 or older with income from work or unemployment benefits (of at least ≈900 USD/year) can claim SA benefits in case of reduced work capacity due to disease or injury; students are also included to some extent. For employees, benefits are paid by the employer during the first 14 days, and thereafter by the Social Insurance Agency.38 A medical certificate is required from the eighth day of the SA spell. All residents aged 19 to 65 years, irrespective of whether they had income earlier, can be granted DP if their work capacity is long-term or permanently reduced due to disease or injury. The SA benefits cover 80% and the DP benefit 65% of the lost income, up to a certain level. Both SA and DP may be granted for full-time or part-time (25%, 50% or 75%) of ordinary work hours. This means that people can be on part-time SA and DP at the same time. Therefore, we calculated net days, for example, 2 days of 50% of SA or DP represent 1 net day.

All pregnant women can choose to request parental benefit 60 days before the estimated delivery date. Parental benefit is granted for 480 days for one child (in case of singleton births), with 180 additional days per child in case of multiple pregnancies. For 390 of these days, the benefit is based on the income, while for the remaining 90 days, the benefit is set to 180 SEK per day. The parental leave days may be used anytime until the child’s eighth birthday, by either of the child’s parents, except for 60 days that were reserved for the mother and 60 days that were reserved for the father during the years under study. If a parent on parental leave is too ill to care for the child, he/she may apply for SA, and thus be on SA instead of parental leave while someone else takes care of the child.

Outcomes

We used the following measures of SA and DP as outcomes:

The mean numbers of SA and DP net days/year were calculated for each of the 6 years Y−3 to Y+3.

General SA, defined as the first SA spell regardless of duration in Y+2 to Y+3.

Long-term SA, defined as the first SA spell of >90 net days in Y+2 to Y+3.

DP, defined as the first new DP spell in Y+2 to Y+3.

Nulliparous women with miscarriages, abortions, hysterectomies, stillbirths and unsuccessful fertilisation treatments were retained in the analyses and could be in any of the three groups. Women in long-term care facilities were followed with the registers similarly to women in the general population. Women who died or emigrated during the follow-up were censored when these events occurred.

Included factors

We included age (18 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, and 35 to 39 years); educational level (elementary (≤9 years+missing), high school (10 to 12 years) and university/college (>12 years)) in December 2004; country of birth (Sweden, other Northern European country, other European country and rest of the world); and type of living area (large city, medium-sized city and small city/rural); and previous hospitalisation and specialised outpatient healthcare during Y−1 to Y−3 as covariates.

Statistical analyses

We compared characteristics of the three childbirth groups by means of χ2 tests in case of categorical variables and Wilcoxon tests in case of continuous/count variables. We performed Cox proportional hazards regression models to investigate associations between the combinations of childbirth, morbidity, and the risks of future SA and DP. HRs and 95% CIs for SA and DP were calculated. We tested the assumption of proportional hazards with log negative log curves; there was no indication for non-proportionality of hazards. In these analyses we excluded the 21 848 women on DP before T0 as they were not at risk of future SA or DP. Follow-up started at the beginning of Y+2 and ended on the event, emigration, death or the end of Y+3, or at 31 December 2018, whichever came first. When performing analyses with SA as the outcome, we censored also for DP during the follow-up since persons with DP are not at risk for SA. We performed crude models and models adjusted for age, educational level, country of birth, type of living area, hospitalisation and specialised outpatient healthcare before T0. Analyses were also performed among parous women only (B1 and B1+; n=38 413) in order to examine the potential differences between women in the B1 and B1+ groups, respectively. We performed analysis regarding collinearity diagnostics between morbidity during Y−3 to Y−1 and Y+1, but found no strong indication for collinearity for these measures.

All analyses were conducted by SAS statistical software, V.9.4.

Patient and public involvement

The study participants or the general public were not involved in decisions about the research question, the design of the study, the outcomes, the conduct of the study, the drafting of the paper nor in the dissemination of the study results.

Results

Among the 492 504 women, 38 972 (7.9%) had at least one childbirth during the study period, that is, were in the B1 or B1+ groups (table 1). The majority of the women in B1 or B1+ were younger than 30 years and had a somewhat higher educational level than those in the B0 group. Further characteristics of the three childbirth groups are presented in table 1. A higher proportion of the women in B1 or B1+ had at least one SA spell before and/or after T0 than the B0 women. On the contrary, compared with women in B1 or B1+, a higher proportion of the B0 women had DP.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the cohort of women* by childbirth group (n=492 504)

| Factors | B0 (n=453 532) | B1 (n=14 299) | B1+ (n=23 673) | P value† |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age in 2004 (years) | <0.001 | |||

| 18 to 24 | 257 219 (56.7) | 3688 (25.8) | 5284 (21.4) | |

| 25 to 29 | 92 672 (20.4) | 4593 (32.1) | 10 354 (42.0) | |

| 30 to 34 | 56 233 (12.4) | 4089 (28.6) | 7614 (30.9) | |

| 35 to 39 | 47 408 (10.5) | 1929 (13.5) | 1421 (5.8) | |

| Country of birth | <0.001 | |||

| Sweden | 397 091 (87.6) | 12 388 (86.6) | 22 583 (91.5) | |

| Other Northern European | 4873 (1.1) | 200 (1.4) | 237 (1.0) | |

| Other European countries | 7432 (1.6) | 213 (1.5) | 242 (1.0) | |

| Rest of the world | 44 136 (9.7) | 1498 (10.5) | 1611 (6.5) | |

| Type of living area in 2004 | <0.001 | |||

| Large cities | 196 911 (43.4) | 6260 (43.8) | 10 882 (44.1) | |

| Medium-sized cities | 161 919 (35.7) | 4824 (33.7) | 8425 (34.2) | |

| Small cities/rural | 94 702 (20.9) | 3215 (22.5) | 5366 (21.8) | |

| Educational attainment in 2004 | <0.001 | |||

| Elementary (≤9 years) | 90 510 (20.0) | 1815 (12.7) | 1757 (7.1) | |

| High school (10 to 12 years) | 208 184 (45.9) | 6751 (47.2) | 9516 (38.6) | |

| University/college (≥13 years) | 154 838 (34.1) | 5733 (40.1) | 13 400 (54.3) | |

| Family situation in 2004 | <0.001 | |||

| Married or cohabitant | 20 295 (4.5) | 3212 (22.5) | 6843 (27.7) | |

| Single | 433 237 (95.5) | 11 087 (77.5) | 17 830 (72.3) | |

| Hospitalisation (at least 1 day during): | ||||

| Y−3 to Y−1 | 50 184 (11.1) | 8074 (56.5) | 13 145 (53.3) | <0.001 |

| Excluding ICD-10: O and Z30-Z39 | 49 040 (10.8) | 1726 (12.2) | 2210 (9.0) | <0.001 |

| Y+1 to Y+3 | 49 430 (10.9) | 13 975 (97.7) | 24 547 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| Excluding ICD-10: O and Z30-Z39 | 47 892 (10.6) | 1691 (11.8) | 1924 (7.8) | <0.001 |

| Y−3 to Y+3 | 14 865 (3.3) | 7773 (54.4) | 13 024 (52.8) | <0.001 |

| Excluding ICD-10: O and Z30-Z39 | 14 436 (3.2) | 439 (3.1) | 372 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Specialised outpatient visit (at least one visit during): | ||||

| Y−3 to Y−1 | 256 677 (56.6) | 12 130 (84.8) | 19 916 (80.7) | <0.001 |

| Excluding ICD-10: O and Z30-Z39 | 254 531 (56.1) | 10 286 (71.9) | 16 323 (66.2) | <0.001 |

| Y+1 to Y+3 | 264 932 (58.4) | 9870 (69.0) | 19 625 (79.5) | <0.001 |

| Excluding ICD-10: O and Z30-Z39 | 261 766 (57.7) | 9063 (63.4) | 15 489 (62.8) | <0.001 |

| Y−3 to Y+3 | 180 667 (39.8) | 8737 (61.1) | 16 520 (67.0) | <0.001 |

| Excluding ICD-10: O and Z30-Z39 | 177 748 (39.2) | 7165 (50.1) | 11 376 (46.1) | <0.001 |

| At least one SA spell during: | ||||

| Y−3 to Y−1 | 54 013 (11.9) | 5840 (40.8) | 8802 (35.7) | <0.001 |

| Y+1 to Y+3 | 61 341 (13.5) | 2797 (19.6) | 7447 (30.2) | <0.001 |

| Y−3 to Y+3 | 90 849 (20.0) | 6740 (47.1) | 11 940 (48.4) | <0.001 |

| Disability pension any time during: | ||||

| Y−3 to Y−1 | 21 289 (4.7) | 351 (2.5) | 208 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Y+1 to Y+3 | 27 453 (6.1) | 438 (3.1) | 238 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Y−3 to Y+3 | 28 121 (6.2) | 467 (3.3) | 256 (1.0) | <0.001 |

B0=no childbirth in 2005 nor in the following 3 years+43 weeks; B1=first child in 2005 and no more deliveries in the following 3 years+43 weeks; B1+=first child in 2005 and at least one more delivery in the following 3 years+43 weeks; Y−3=3 years before delivery/index date; Y-−1=1 year before delivery/index date; Y+1=1 year after delivery/index date; Y+3=3 years after delivery/index date; T0=delivery date, or in the B0 group: 2 July 2005.

*Nulliparous women aged 18 to 39 years in December 2004 registered as residents in Sweden between 2002 and 2004.

†The p value corresponds to χ2 tests in case of categorical variables and to Wilcoxon tests in case of continuous/count variables.

SA, sickness absence.

The mean annual number of hospitalisation days and visits to specialised outpatient healthcare are presented in figure 1. Figure 1C shows that when healthcare with diagnoses for pregnancy and childbirth are excluded, women in the B1 and B1+ groups had lower number of hospitalisation days than women in B0, particularly the women in B1+; outside the period of pregnancy, women in B1+ had a lower number of specialised outpatient visits than women in B0 (figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Mean annual number of hospitalisation days and specialised outpatient visits (with 95% CI).

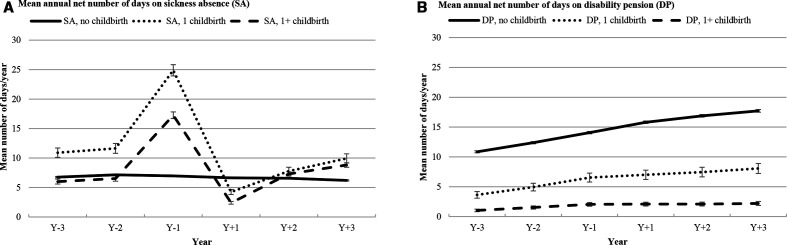

Women in B1 or B1+ had more SA days during the year before T0, especially in the B1 group (figure 2). After T0, the number of SA days for these women dropped rapidly to a lower level than for women in B0, that is, in that year most women were on parental leave benefits. However, in all studied years, women in B0 had a higher mean number of DP days/year than women in B1 or B1+. Women in B1+ had the lowest mean number of DP days/year compared with both B0 and B1+.

Figure 2.

Mean annual number of days on sickness absence and/or disability pension (with 95% CI).

Table 2 presents crude and multivariate HR and 95% CI for the association between morbidity in Y+1 after T0 and future SA among all not on DP at T0, for each of the three childbirth groups. Those on DP at T0 were excluded as they were not at risk of new DP or SA. First, all three groups (B0, B1 and B1+) were compared, then the two childbirth groups (B1 and B1+) were compared. In the fully adjusted models, the HR of future SA was compared between the groups, using women in the B0 group with no such morbidity as reference group. In the B0 group with such morbidity, the SA risk was approximately threefold higher in Y+2to Y+3. Actually, the women in B1, without morbidity in Y+1 had a lower risk of future SA compared with B0 women without such morbidity. Those in B1+, without morbidity at Y+1, had a lower risk of long-term SA (>90 days) in Y+2 to Y+3, however, a higher risk for any SA.

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted HRs and 95% CIs for the association between childbirth, morbidity 1 year after T0 and new SA in the second and third year after T0*

| Morbidity† | SA in Y+2 to Y+3 (regardless of number of SA days) | Long-term SA (>90 days) in Y+2 to Y+3 | ||||||

| N/Outcome | HRs (95% CIs) | N/Outcome | HRs (95% CIs) | |||||

| Crude | Model 1‡ | Model 2§ | Crude | Model 1‡ | Model 2§ | |||

| All women (n=4 70 656) | ||||||||

| B0, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 417 592/39 911 | * | * | * | 417 592/12 614 | * | * | * |

| B0, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 14 651/3891 | 3.29 (3.18 to 3.40) | 3.24 (3.14 to 3.35) | 2.56 (2.48 to 2.65) | 14 651/1855 | 4.61 (4.39 to 4.84) | 4.51 (4.30 to 4.74) | 3.33 (3.16 to 3.50) |

| B1, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 13 425/1837 | 1.45 (1.38 to 1.52) | 1.14 (1.09 to 1.20) | 0.81 (0.77 to 0.85) | 13 425/590 | 1.46 (1.34 to 1.58) | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.14) | 0.68 (0.62 to 0.74) |

| B1, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 523/153 | 3.61 (3.08 to 4.23) | 2.89 (2.46 to 3.38) | 1.87 (1.59 to 2.19) | 523/81 | 5.66 (4.55 to 7.04) | 4.21 (3.38 to 5.24) | 2.43 (1.95 to 3.02) |

| B1+, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 23 947/6451 | 3.01 (2.93 to 3.09) | 2.50 (2.43 to 2.57) | 1.82 (1.77 to 1.87) | 23 947/1212 | 1.67 (1.58 to 1.78) | 1.26 (1.18 to 1.34) | 0.84 (0.79 to 0.89) |

| B1+, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 518/233 | 5.95 (5.23 to 6.77) | 5.01 (4.40 to 5.69) | 3.32 (2.92 to 3.78) | 518/67 | 4.48 (3.52 to 5.70) | 3.41 (2.68 to 4.34) | 2.03 (1.59 to 2.58) |

| Women who had at least one childbirth (n=38 413) | § | |||||||

| B1, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 13 425/1837 | * | * | * | 13 425/590 | * | * | * |

| B1, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 523/153 | 2.54 (2.15 to 3.00) | 2.52 (2.14 to 2.97) | 2.38 (2.02 to 2.81) | 523/81 | 3.93 (3.12 to 4.96) | 3.85 (3.05 to 4.85) | 3.55 (2.81 to 4.48) |

| B1+, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 23 947/6451 | 2.10 (2.00 to 2.22) | 2.17 (2.06 to 2.29) | 2.20 (2.09 to 2.32) | 23 947/1212 | 1.15 (1.04 to 1.27) | 1.21 (1.09 to 1.33) | 1.23 (1.11 to 1.36) |

| B1+, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 518/233 | 4.26 (3.72 to 4.89) | 4.44 (3.87 to 5.08) | 4.23 (3.69 to 4.85) | 518/67 | 3.10 (2.41 to 3.99) | 3.21 (2.49 to 4.13) | 2.99 (2.32 to 3.85) |

T0=delivery date or equivalent; Y+2=two years after delivery/index date; Y+3=3 years after delivery/index date; B0=no childbirth in 2005 nor in the following 3 years+43 weeks; B1=first child in 2005 and no more deliveries in the following 3 years+43 weeks; Y+1=1 year after delivery/index date; B1+=first child in 2005 and at least one more delivery in the following 3 years+43 weeks.

*Women on DP at baseline were excluded.

†Morbidity: measured by hospitalisation and specialised outpatient visit.

‡Model 1: adjusted for age, education, country of birth and type of living area.

§Model 2: adjusted for age, education, country of birth, type of living area, and previous hospitalisation and specialised outpatient visit.

¶Diagnoses O00-O99 and Z30-Z39 were excluded.

DP, disability pension; SA, sickness absence.

When restricting the analyses to those who had given birth, that is, to the women in B1 and B1+ (n=38 413), those in B1 +with morbidity in Y+1 had a particularly high risk of any SA compared with all other groups. When again excluding those on DP at T0, the HR for future DP was highest in the B0 group with morbidity in Y+1, using the women in B0 with no morbidity in Y+1 as reference group (table 3). Regardless of morbidity, parous women, particularly those in B1+, had a lower risk of DP than women in B0. When restricting the analyses to only women in B1 and B1+, morbidity was associated with having DP in Y+2 to Y+3, especially in the B1 group. That is, those with more than one birth had lower risk of DP.

Table 3.

HRs and 95% CIs for the association between childbirth, morbidity 1 year after T0 and new DP in the second and third year after T0*

| Morbidity† | N/Outcome | HRs and 95% CIs for DP in Y+2 to Y+3 | ||

| Crude | Model 1‡ | Model 2§ | ||

| All women (n=470 656) | ||||

| B0, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 417 592/5374 | * | * | * |

| B0, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 14 651/1391 | 7.72 (7.28 to 8.19) | 6.88 (6.48 to 7.30) | 4.11 (3.87 to 4.37) |

| B1, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 13 425/90 | 0.52 (0.42 to 0.64) | 0.41 (0.33 to 0.50) | 0.20 (0.16 to.24) |

| B1, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 523/25 | 3.77 (2.55 to 5.59) | 2.82 (1.90 to 4.17) | 1.17 (0.79 to 1.73) |

| B1+, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 23 947/39 | 0.13 (0.09 to 0.17) | 0.11 (0.08 to 0.16) | 0.06 (0.04 to 0.08) |

| B1+, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 518/8 | 1.20 (0.60 to 2.40) | 1.01 (0.50 to 2.01) | 0.43 (0.21 to 0.85) |

| Women who had at least one childbirth (n=38 413) | ||||

| B1, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 13 425/90 | * | * | * |

| B1, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 523/25 | 7.32 (4.70 to 11.40) | 6.27 (4.02 to 9.79) | 5.68 (3.63 to 8.87) |

| B1+, no morbidity in Y+1¶ | 23 947/39 | 0.24 (0.17 to 0.35) | 0.28 (0.19 to 0.41) | 0.28 (0.19 to 0.42) |

| B1+, morbidity in Y+1¶ | 518/8 | 2.32 (1.12 to 4.77) | 2.30 (1.12 to 4.75) | 2.07 (1.00 to 4.27) |

T0=delivery date or among those in B0: 2 July 2005; Y+2=2 years after delivery/index date; Y+3=3 years after delivery/index date; B0=no childbirth in 2005 nor in the following 3 years+43 weeks; Y+1=1 year after delivery/index date; B1=first child in 2005 and no more deliveries in the following 3 years+43 weeks; B1+=first child in 2005 and at least one more delivery in the following 3 years+43 weeks.

*Women on DP at baseline were excluded.

†Morbidity: measured by hospitalisation and specialised outpatient visit.

‡Model 1: adjusted for age, education, country of birth and type of living area.

§Model 2: adjusted for age, education, country of birth, type of living area, and previous hospitalisation and specialised outpatient visit.

¶Diagnoses O00-O99 and Z30-Z39 were excluded.

DP, disability pension.

When investigating the associations between the amount of morbidity (classified as no morbidity, morbidity before T0, morbidity after T0 and morbidity both before and after T0) and the risk of SA and DP in Y+2 to Y+3 among women who gave birth, we found a gradient across these categories; there was a particularly high risk of future SA and DP among women with morbidity both before and after T0 (tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

HRs and 95% CIs for the association between morbidity before and after the first birth and new SA in the second and third year after T0 in women who had at least one childbirth (n=38 413)*

| Morbidity† | HRs and 95% CIs | |||||

| SA in Y+2 to Y+3 (regardless of the number of days) | Long-term SA (>90 days) in Y+2 to Y+3 | |||||

| N/Outcome | Crude | Model 1‡ | N/Outcome | Crude | Model 1‡ | |

| No morbidity during Y−3 to Y−1 or Y+1§ | 19 531/3825 | * | * | 19 531/742 | * | * |

| Morbidity during Y−3 to Y−1 but not during Y+1§ | 17 841/4463 | 1.33 (1.28 to 1.39) | 1.34 (1.28 to 1.40) | 17 841/1060 | 1.59 (1.44 to 1.74) | 1.57 (1.42 to 1.72) |

| No morbidity during Y−3 to Y−1 but during Y+1§ | 373/123 | 1.95 (1.63 to 2.34) | 1.96 (1.64 to 2.35) | 373/51 | 3.91 (2.94 to 5.19) | 3.84 (2.89 to 5.09) |

| Morbidity both during Y−3 to Y−1 and Y+1§ | 668/263 | 2.50 (2.21 to 2.83) | 2.57 (2.27 to 2.91) | 668/97 | 4.19 (3.39 to 5.18) | 4.09 (3.31 to 5.06) |

T0=delivery date or equivalent; Y+2=2 years after delivery; Y+3=3 years after delivery; Y−3=3 years before delivery; Y−1=1 year before delivery; Y+1=1 year after delivery.

*Women on DP at baseline were excluded.

†Morbidity: measured by hospitalisation and specialised outpatient visit.

‡Model 1: adjusted for age, education, country of birth and type of living area.

§Diagnoses O00-O99 and Z30-Z39 were excluded.

DP, disability pension; SA, sickness absence.

Table 5.

HRs and 95% CIs for the association between morbidity before and after the first birth and new DP in the second and third year after T0 in women who had at least one childbirth (n=38 413)*

| Morbidity†‡ | N/Outcome | HRs and 95% CIs for DP in Y+2 to Y+3 | |

| Crude | Model 1†‡ | ||

| No morbidity during Y−3 to Y−1 or Y+1§ | 19 531/41 | * | * |

| Morbidity during Y−3 to Y−1 but not during Y+1§ | 17 841/88 | 2.35 (1.62 to 3.41) | 2.13 (1.47 to 3.10) |

| No morbidity during Y−3 to Y−1 but during Y+1§ | 373/9 | 11.70 (5.69 to 24.06) | 9.90 (4.80 to 20.42) |

| Morbidity both during Y−3 to Y−1 and Y+1§ | 668/24 | 17.45 (10.54 to 28.87) | 13.20 (7.92 to 21.98) |

T0=delivery date or equivalent; Y+2=2 years after delivery/index date; Y+3=3 years after delivery/index date; Y-3=3 years before delivery/index date; Y−1=1 year before delivery/index date; Y+1=1 year after delivery/index date.

*Women on DP at baseline were excluded.

†‡Morbidity: measured by hospitalisation and specialised outpatient visit.

‡Model 1: adjusted for age, education, country of birth and type of living area.

§Diagnoses O00-O99 and Z30-Z39 excluded.

DP, disability pension.

Discussion

In this longitudinal, population-based cohort study of 492 504 women in Sweden, we investigated the associations of morbidity (ie, hospitalisation, specialised outpatient healthcare that is not related to pregnancy, childbirth or postpartum) with future SA and DP in our three groups of initially nulliparous women, that is, B0, B1 and B1+. During Y−1 parous women had higher mean number of SA days than women in B0. This decreased gradually during the years after T0. On the other hand, over all the six studied years the women in the B0 group had a higher number of DP days than women in B1 and B1+. When excluding those on DP at T0, we found that morbidity was strongly associated with a higher risk of future SA and DP, regardless of childbirth status. Analyses focussing solely on women who gave birth showed that morbidity both before and after the first childbirth was associated with a particularly high risk of future SA and DP.

Research has repeatedly shown that women have a higher probability of having SA or DP than men 39 40 and pregnancy/childbirth is considered to be one of the reasons behind this difference.6–8 28 41 Our results that SA days increased in Y−1, that is, during pregnancy, as well as that the number became much lower in Y+1 (when most are on parental leave) are in line with some previous studies.6 12 15 29 42 43 The somewhat higher levels of SA in Y+3 could be explained by the double-burden hypothesis which suggests that the combination of paid work and parenthood may lead to worse health.44–47 However, several other studies have suggested that multiple roles are likely to be beneficial to women’s health.48–50 A Norwegian study also reported a higher level of SA in the years after pregnancy, which disappeared after accounting for SA during subsequent pregnancies.47 Moreover, women who remained nulliparous had higher levels of DP than those who gave birth. Our findings also showed higher mean number of hospitalisation days among nulliparous women, indicating that there might be a health selection into pregnancy.

Women with morbidity that was not related to pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period after delivery, had an overall higher risk for future SA, regardless of childbirth status than the other women. This association persisted even after adjustment for age, education and previous morbidity. Women in B1 had a lower risk of any SA and of long-term SA than those in B0 (>90 days), whereas women who had more than one birth had a higher risk of any SA but a lower risk of long-term SA in Y+2 to Y+3. It is likely that the new pregnancy(ies) during the follow-up time resulted in SA for women in the B1+ group. Our finding regarding an inverse association between the number of births and DP might indicate better health among the women in the B1+ group than in the other two groups. These findings are also in line with two Swedish prospective cohort studies of female twins.11 29 Comparison of women who gave birth to one child only with those who gave birth to several children, showed similar graded associations between morbidity and future SA/DP as when we compared parous women with nulliparous women.

It has often been questioned by mass media, employers and policymakers whether the higher SA among women—and in particular among women with small children—is due to really being ill or whether they use SA as a means to ease their ‘double burden’ arising from work and domestic duties.28 Nevertheless, we found that morbidity both before and after delivery was the strongest risk factor for SA and DP among women who gave birth. We observed a graded association between morbidity and SA/DP; women with morbidity before or after their first childbirth had a higher risk of SA and DP than those without morbidity, whereas those with morbidity both before and after the first childbirth had even higher risks. This suggests the presence of a dose-response association between morbidity and higher future SA/DP risk. Also, this is in line with our previous studies of Swedish twin sisters.11 29 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to document associations between morbidity and SA/DP among women of childbearing age in the general population, using data on both hospitalisation and specialised outpatient healthcare as well as on number of childbirths.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the population-based longitudinal cohort design, that all women fulfilling the inclusion criteria could be included (not only a sample) and the large cohort allowing for subgroup analyses. Other strengths are the possibility to use extensive microdata linked from several high-quality nationwide administrative registers,51–53 instead of self-reports that are limited by, for example, recall bias and drop-outs. It was also an advantage that all study participants could be followed from date of birth or equivalent, rather than by calendar years. The universal coverage of the Swedish public SA/DP insurance system further reduces selection bias and misclassification of the outcome. Another strength is that we could use also the National Patient Register to identify the childbirths not registered in the Medical Birth Register. Additionally, the high employment rates among women on the Swedish labour market limits54 bias due to health selection into paid work, that is, if a very large proportion of the population is in paid work, more persons with different type of morbidity are in paid work.

There are, however, some limitations that should be mentioned. First, some immigrant women might only have given birth before coming to Sweden; they would consequently be inappropriately categorised as nulliparous. The Medical Birth Register has information on whether the woman had previous births, also outside of Sweden, however, not the Patient Register. To reduce such misclassification, we only included women who lived in Sweden for at least 3 years prior to inclusion in the study. If there were any such misclassification, it probably led to underestimation of SA and DP in the B0 group and does thus not affect our conclusions. It is important to be aware of that we studied women who gave birth, irrespective of if they lived with the child or lived with other children. For instance, the child might have died or the women given it up for adoption—also, nulliparous women might live with children they did not give birth to. Another aspect is that SA spells ≤14 days were not included, something that can be seen both as a limitation and a strength. The SA spells ≤14 days only account for a limited number of all SA days and most of them are not verified by a physician certificate.55 Furthermore, since the Patient Register includes only information on inpatient and specialised outpatient healthcare, we could not include in our definition of morbidity information from primary healthcare.

Conclusion

It has been questioned whether sickness absent women with children are actually ill or rather ease their ‘double burden’ through claiming SA.28 In this study, we found a strong association between morbidity and both SA and DP among women of childbearing ages after controlling for morbidity before baseline and for several demographic factors. It has also been suggested that women with more children have more SA. We found the opposite; women with one birth had a lower future SA and DP risk than those who did not give birth, while those who gave birth more than once had the lowest risk of DP. Our findings may inform the debate in welfare states concerning the presence of morbidity in women on SA, in particular among women with young children.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MW conducted the analyses, wrote the first draft and revised the paper; KL contributed to writing, interpretation of the findings and revised the paper; PS and KA contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the findings and revised the paper; LN contributed to the interpretation of the findings, writing and revised the paper. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was financially supported by AFA Insurance (grant number 160318) and the Swedish Research Council (grant number 2017-00624). The funder was not involved in the study design, collection or analysis of the data, interpretation of the results, writing of the paper nor in decisions about the manuscript submission.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The project was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1.Alexanderson K, Norlund A. Swedish Council on technology assessment in health care (SBU). Chapter 1. AIM, background, key concepts, regulations, and current statistics. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2004;63:12–30. 10.1080/14034950410021808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parrukoski S, LammiTaskula J. Parental leave policies and the economic crisis in the Nordic countries. Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svedberg P, Ropponen A, Alexanderson K, et al. Genetic susceptibility to sickness absence is similar among women and men: findings from a Swedish twin cohort. Twin Res Hum Genet 2012;15:642–8. 10.1017/thg.2012.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ugreninov E. Can family policy reduce mothers’ sick leave absence? A causal analysis of the Norwegian paternity leave reform. J Fam Econ Issues 2013;34:435–46. 10.1007/s10834-012-9344-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mastekaasa A.Parenthood, gender and sickness absence. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1827–42. 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00420-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexanderson K, Hensing G, Carstensen J, et al. Pregnancy-related sickness absence among employed women in a Swedish County. Scand J Work Environ Health 1995;21:191–8. 10.5271/sjweh.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexanderson K, Hensing G, Leijon M, et al. Pregnancy related sickness absence in a Swedish County, 1985-87. J Epidemiol Community Health 1994;48:464–70. 10.1136/jech.48.5.464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexanderson K, Sydsjö A, Hensing G, et al. Impact of pregnancy on gender differences in sickness absence. Scand J Soc Med 1996;24:169–76. 10.1177/140349489602400308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vistnes JP. Gender differences in days lost from work due to illness. ILR Review 1997;50:304–23. 10.1177/001979399705000207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angelov N, Johansson P, Lindahl E. Gender differences in sickness absence and the gender division of family responsibilities. Uppsala: Institute for Evaluation of Labour market and Education Policy (IFAU), 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Björkenstam E, Alexanderson K, Narusyte J, et al. Childbirth, hospitalisation and sickness absence: a study of female twins. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006033. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narusyte J, Björkenstam E, Alexanderson K, et al. Occurrence of sickness absence and disability pension in relation to childbirth: a 16-year follow-up study of 6323 Swedish twins. Scand J Public Health 2016;44:98–105. 10.1177/1403494815610051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall k RE, Telle K. Sick leave before, during and after pregnancy: Statistics Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Floderus B, Hagman M, Aronsson G, et al. Medically certified sickness absence with insurance benefits in women with and without children. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:85–92. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.László KD, Björkenstam C, Svedberg P, et al. Sickness absence and disability pension before and after first childbirth and in nulliparous women by numerical gender segregation of occupations: a Swedish population-based longitudinal cohort study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0226198. 10.1371/journal.pone.0226198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Björkenstam C, László KD, Orellana C, et al. Sickness absence and disability pension in relation to first childbirth and in nulliparous women according to occupational groups: a cohort study of 492,504 women in Sweden. BMC Public Health 2020;20:686. 10.1186/s12889-020-08730-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soma-Pillay P, Nelson-Piercy C, Tolppanen H, et al. Physiological changes in pregnancy. Cardiovasc J Afr 2016;27:89–94. 10.5830/CVJA-2016-021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams D. Pregnancy: a stress test for life. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2003;15:465–71. 10.1097/00001703-200312000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piccinni M-P, Lombardelli L, Logiodice F, et al. How pregnancy can affect autoimmune diseases progression? Clin Mol Allergy 2016;14:11. 10.1186/s12948-016-0048-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khatun M, Clavarino AM, Callaway L, et al. Common symptoms during pregnancy to predict depression and health status 14 years post partum. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;104:214–7. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown MC, Best KE, Pearce MS, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol 2013;28:1–19. 10.1007/s10654-013-9762-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Männistö T, Mendola P, Vääräsmäki M, et al. Elevated blood pressure in pregnancy and subsequent chronic disease risk. Circulation 2013;127:681–90. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.128751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller JM, Low LK, Zielinski R, et al. Evaluating maternal recovery from labor and delivery: bone and levator ani injuries. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:188.e1–188.e11. 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sedgh G, Singh S, Hussain R. Intended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trends. Stud Fam Plann 2014;45:301–14. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00393.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng C-Y, Li Q. Integrative review of research on general health status and prevalence of common physical health conditions of women after childbirth. Womens Health Issues 2008;18:267–80. 10.1016/j.whi.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Romito P, Lelong N, et al. Women’s health after childbirth: a longitudinal study in France and Italy. BJOG 2000;107:1202–9. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11608.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Troy NW. A comparison of fatigue and energy levels at 6 weeks and 14 to 19 months postpartum. Clin Nurs Res 1999;8:135–52. 10.1177/10547739922158205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angelov N, Johansson P, Lindahl E. Sick of family responsibilities? Empirical Economics 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Björkenstam E, Narusyte J, Alexanderson K, et al. Associations between childbirth, hospitalization and disability pension: a cohort study of female twins. PLoS One 2014;9:e101566. 10.1371/journal.pone.0101566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allebeck P, Mastekaasa A. Swedish Council on technology assessment in health care (SBU). Chapter 3. causes of sickness absence: research approaches and explanatory models. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2004;63:36–43. 10.1080/14034950410021835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Englund L, Tibblin G, Svärdsudd K. Variations in sick-listing practice among male and female physicians of different Specialities based on case vignettes. Scand J Prim Health Care 2000;18:48–52. 10.1080/02813430050202569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sydsjö A, Sydsjö G, Kjessler B. Sick leave and social benefits during pregnancy--a Swedish-Norwegian comparison. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997;76:748–54. 10.3109/00016349709024341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sydsjö G, Sydsjö A. Newly delivered women’s evaluation of personal health status and attitudes towards sickness absence and social benefits. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2002;81:104–11. 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2002.810203.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsson C, Sydsjö A, Alexanderson K, et al. Obstetricians' attitudes and opinions on sickness absence and benefits during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2006;85:165–70. 10.1080/00016340500430345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, et al. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659–67. 10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludvigsson JF, Svedberg P, Olén O, et al. The longitudinal integrated database for health insurance and labour market studies (LISA) and its use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2019;34:423–37. 10.1007/s10654-019-00511-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision (ICD-10). Chapter V (F). Geneva: WHO, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Social insurance in figures, 2016 Stockholm, the Swedish social insurance agency, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leinonen T, Viikari-Juntura E, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, et al. Labour market segregation and gender differences in sickness absence: trends in 2005-2013 in Finland. Ann Work Expo Health 2018;62:438–49. 10.1093/annweh/wxx107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allebeck P, Mastekaasa A. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 5. Risk factors for sick leave - general studies. Scand J Public Health Suppl 2004;63:49–108. 10.1080/14034950410021853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Åkerlind I, Alexanderson A, Hensing G, et al. Sex differences in sickness absence, in relation to parental status. Scand J Soc Med 1995;4:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sydsjö A, Sydsjö G, Alexanderson K. Influence of pregnancy-related diagnoses on sick-leave data in women aged 16-44. J Womens Health Gend Based Med 2001;10:707–14. 10.1089/15246090152563597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Björkenstam C, Orellana C, László KD, et al. Sickness absence and disability pension before and after first childbirth and in nulliparous women: longitudinal analyses of three cohorts in Sweden. BMJ Open 2019;9:e031593. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lidwall U, Marklund S, Voss M. Work-family interference and long-term sickness absence: a longitudinal cohort study. Eur J Public Health 2010;20:676–81. 10.1093/eurpub/ckp201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Väänänen A, Kevin MV, Ala-Mursula L, et al. The double burden of and negative spillover between paid and domestic work: associations with health among men and women. Women Health 2004;40:1–18. 10.1300/J013v40n03_01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blank N, Diderichsen F. Short-Term and long-term sick-leave in Sweden: relationships with social circumstances, working conditions and gender. Scand J Soc Med 1995;23:265–72. 10.1177/140349489502300408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rieck KME, Telle K. Sick leave before, during and after pregnancy. Acta Sociol 2013;56:117–37. 10.1177/0001699312468805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McMunn A, Bartley M, Hardy R, et al. Life course social roles and women's health in mid-life: causation or selection? J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:484–9. 10.1136/jech.2005.042473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lahelma E, Arber S, Kivelä K, et al. Multiple roles and health among British and Finnish women: the influence of socioeconomic circumstances. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:727–40. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00105-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fokkema T. Combining a job and children: contrasting the health of married and divorced women in the Netherlands? Soc Sci Med 2002;54:741–52. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00106-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cnattingius S, Ericson A, Gunnarskog J, et al. A quality study of a medical birth registry. Scand J Soc Med 1990;18:143–8. 10.1177/140349489001800209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ludvigsson JF, Almqvist C, Bonamy A-KE, et al. Registers of the Swedish total population and their use in medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:125–36. 10.1007/s10654-016-0117-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Labour Force Surveys: Fourth Quarter 2017 Statistics Sweden, Stockholm, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hensing G, Alexanderson K, Allebeck P, et al. How to measure sickness absence? literature review and suggestion of five basic measures. Scand J Soc Med 1998;26:133–44. 10.1177/14034948980260020201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.