Highlights

-

•

Mothers display ongoing hesitancy and misinformation post vaccine acceptance for their child.

-

•

Mistrust and hesitancy occur from three sources: physicians, peer networks and the media.

-

•

Mothers believe other mothers should question provider HPV vaccine recommendation.

-

•

Mothers blame the media for HPV vaccine confusion.

Keywords: Vaccine hesitancy, Human papillomavirus, Parents, Misinformation, Confusion, Qualitative

Abstract

Although licensed since 2006, US HPV vaccination rates remain suboptimal. Since mothers are decision-makers for young adults’ vaccination, assessing ongoing knowledge deficits and misunderstanding among parents is important for determining the content and mode of interventions to reach parents. Guided by the social-ecological model and health belief model, 30 interviews with vaccine accepting mothers in the U.S. Midwest were conducted from January through June 2020. Researchers examined ecological determinants of acceptance, perceptions of vaccination barriers, and perceived cues to action for empowering other mothers to vaccinate their children. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis. Results found vaccine accepting mothers exhibited ongoing misconceptions and negative attitudes toward HPV vaccine. Physicians, peers and the media were identified as primary pro-HPV vaccine sources, yet hesitancy and misinformation occurred with each source. Trust in provider recommendation was the primary source for decision-making, yet trust was still lacking. While mothers looked to the media for HPV information, the media were identified as the main source of confusion and distrust. Results show that parents who accept the HPV vaccine can still be hesitant. Thus, mothers who have vaccinated their children for HPV may still need attitudinal and educational training prior to establishing them as role models in interventions for empowering other parents to vaccinate their children. Results showing that the media sow confusion and hesitancy also call for more attention to social media policies to guard against misinformation about the HPV vaccine.

1. Introduction

Over 30,000 people are affected by HPV-attributable cancers in the US each year (Johnson et al., 2020). While this is lower than colon cancer ( 101,420) and slightly lower than pancreatic cancer rates (56.770), (American Cancer Society, 2019) it has continuously increased over the last decades (Johnson et al., 2020). The HPV vaccine, which can prevent many cases of these increasing cancers, has been routinely recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for females and males since 2006 and 2011, respectively (Senkomago et al., 2019). The Healthy People 2020 goal for HPV vaccination is 80% series completion for 13 to 15-year-old males and females (Meites et al., 2019), yet HPV vaccination rates remain suboptimal. The National Immunization Survey-Teen (NIS-Teen) findings from 2018 showed that only 53.7% of females and 48.7% of males aged 13 through 17 years had completed the HPV vaccine series. (US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People, 2020)

Many studies have documented relatively high rates of parental hesitancy around the HPV vaccine compared to other childhood vaccines, contributing to delay or refusal of vaccination (Walker et al., 2019, Holman et al., 2014, Facciola et al., 2019). It often may be assumed that behavior mirrors beliefs; that HPV vaccine delayers or refusers hold deeply seated negative beliefs, whereas acceptors hold strong, positive beliefs. However, as Hendrix and colleagues noted, there is not necessarily a close correspondence between vaccine beliefs and behaviors (Newman et al., 2018). Parents who vaccinate may do so because they trust their child’s medical provider or because it is a family expectation but may still feel hesitant about vaccination (Hendrix et al., 2016). Ongoing hesitancy and misinformation among HPV vaccine accepting parents are largely unstudied. Accepting but hesitant parents may still be vulnerable to misinformation and scare tactics employed by anti-vaccination groups. Further, as multiple doses are needed for series completion for older children, parents may choose not to complete a vaccination series or may refuse or delay vaccination for a younger child. Additionally, vaccinating parents who are not confident in their decision cannot serve as strong advocates for HPV vaccination. In order to counter the false narratives disseminated by HPV vaccination opposers, it is important for those who vaccinate to feel confident in their decision to serve as resources for accurate, positive narratives about HPV vaccination and cancer prevention.

The study purpose was to qualitatively explore misinformation and hesitancy among parents who had vaccinated a child against HPV. As interventions built upon multilevel approaches are more likely to be effective and sustained (Hendrix et al., 2016, Leask et al., 2012, Harper et al., 2018), the study was grounded in the social-ecological model to assess the possible range of determinants that parents view as necessary to HPV vaccination decision-making. Social-ecological systems is a model for describing the multiple factors that impact healthcare utilization and decision (Leask et al., 2012). The model underscores how characteristics of the environment influence individual health behavior and outcomes (Harper et al., 2018). It incorporates multiple determinants into different levels of influence on behavior (intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational/community, society, policy) and considers the interaction of behaviors across the different levels of influence, which leads to multi-level behavior intervention suggestions (Leask et al., 2012, Harper et al., 2018). The authors also incorporated the health belief model (HBM) constructs of barriers to identify the challenges/barriers to the social-ecological determinants of decision making and cues to action to assess mothers’ perceived strategies for empowering other parents to vaccinate their children. The HBM has been used extensively to study vaccination beliefs and behaviors and in vaccination research to identify patient perceptions of disease and vaccination (Caperon et al., 2019).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants

Thirty Midwest US mothers who vaccinated a child for HPV were interviewed about the decision-making process. The study focused on mothers because research shows that mothers are the sole decision-makers or share decision-making with their partners for their children’s HPV vaccination 90% of the time (Coe et al., 2009). Mothers were eligible to participate if they had at least one child 9–17 years old who had been HPV vaccinated, resided in the Midwest and were currently employed in a professional health- or education-related field with a bachelor’s degree or higher. The majority of the sample derived from the Marion County/Indianapolis greater metropolitan area. Area sociodemographic characteristics are noted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Demographics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 29–39 | 3 (10.00%) |

| 40–49 | 16 (53.33%) |

| 50–59 | 10 (33.33%) |

| 60+ | 1 (3.34%) |

| Race | |

| White | 16 (53.0%) |

| Black | 12 (40.0%) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (3.5%) |

| Bi-racial | 1 (3.5%) |

| Profession | |

| Health-related | 18 (60.0%) |

| Education | 12 (40.0%) |

| Total Number of Children | |

| 1 | 6 (20.0%) |

| 2 | 15 (50.0%) |

| 3 | 5 (16.7%) |

| 4–6 | 4 (13.3%) |

| Sex of Children in Sample | |

| Female | 30 (58.0%) |

| Male | 22 (42.0%) |

| Age of Children in Sample | |

| 9–11 | 14 (27.0%) |

| 12–15 | 19 (36.5%) |

| 16–17 | 19 (36.5%) |

*Note: Although participants’ exact income was unknown, the average per capita income for the greater Indianapolis Metro area for which the sample was derived was $54,582 in 2018. The area’s racial demographics are 61.4% Caucasian and 28.3% African American. In Marion County, 12% are uninsured and 25% of children live in poverty. Only 0.6% of residents are classified as living in rural areas (Hussain et al., 2018, County Health Rankings, xxxx).

The sample was obtained through a combination of purposive and snowball sampling. The lead author initially approached mothers affiliated with a parent advisory group associated with a midwestern pediatric medical department via email and invited them to participate. They were told the study purpose was to understand their HPV vaccination decisional process to guide and empower other mothers to vaccinate their children.

2.2. Data collection

A semi-structured questionnaire interview guide with open-ended questions to elicit discussion about mothers’ decisions about children’s HPV vaccination was developed by the research team, comprised of researchers in adolescent health psychology, health communication and epidemiology. The guide was developed to address the conceptual frameworks of the social-ecological model and health belief constructs. To assess the determinants of importance to decision making, topics related to each social-ecological level (intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational/community, society, policy) that stemmed from results of multiple studies conducted by the authors were incorporated into the guide (Panozzo et al., 2020, Taylor et al., 2014, Fu et al., 2019, Hoss et al., 2019, Alexander et al., 2015, Alexander et al., 2014, Marlow et al., 2013). The guide was subsequently pilot tested with mothers during preliminary interviews and revised in an iterative manner. As the study’s focus was on HPV vaccination, mothers were first asked to verbally verify that their child was vaccinated for HPV. The interview began with general questions about mothers’ experiences with the HPV vaccine. Mothers were then asked to 1) describe what they remembered about the experience and challenges they may have faced when hearing about HPV vaccination and the thoughts they had when deciding whether to accept it, and 2) to relay how those experiences shaped what they believe could empower or inhibit other mothers’ decisions. The guide also included probing questions for follow-up to allow collection of more detailed and informative responses. (See Appendix A.) The study protocol received IRB approval with exempt status (pro00041072). The requirement for informed consent was waived. Interviews were conducted over the telephone from January 2020 to June 2020. Interviews lasted approximately 30 min. Participants received a $25 gift card for participation.

2.3. Data analysis

Interviews were conducted by the PI, who has experience conducting semi-structured interviewing techniques. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for thematic content analysis using an established approach to identify themes and patterns within the data (Kester et al., 2013, Guest et al., 2012). Initial analysis involved multiple readings of the interview transcripts and discussions among team members to review early impressions and identify emergent themes. Based on discussions and questions in the interview guide, an initial codebook was developed and used to code the interviews. Researchers discussed coded transcripts in an iterative manner to ensure general agreement about the meaning of codes and to identify emergent patterns and themes and reviewed them to confirm they described topics under study. Interviews proceeded until they produced no new information or insight, suggesting theoretical saturation.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

The sample was comprised of 30 mothers aged 30–60 years, with 53% (n = 16) White and 40% African American. (See Table 1 demographics.)

3.2. Model of hesitancy and misinformation

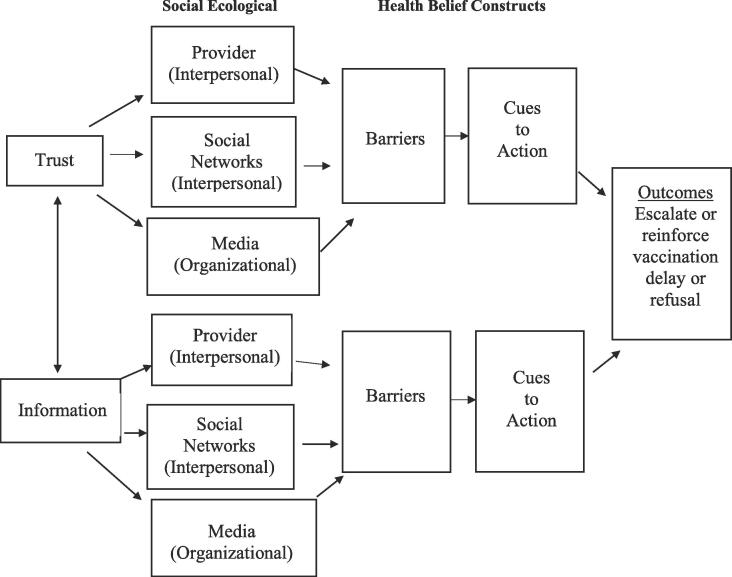

After examining mothers’ vaccination experiences, a model depicting the emergence and route of mothers’ vaccine hesitancy and misinformation emerged (Fig. 1). Model components show that trust and information were the main perceived determinants of mothers’ initial vaccination acceptance, and they looked to physicians, social networks and the media for these attributes. When mothers described their initial decision to vaccinate, they reported barriers from each source that produced distrust and misperception. Their suggestions for aiding other mothers’ decisions indicated that the distrust and misinformation that stemmed from initial barriers often continued. An exception to the model occurred among mothers in medical fields (oncology and nursing, n = 4) who reported no initial hesitancy with provider recommendation. A breakdown of model components and exemplary quotes are presented in Table 2, Table 3.

Fig. 1.

Route and transmission of vaccine hesitancy and misperception.

Table 2.

Model component themes and subthemes.

| Model Components | Themes and [Subthemes] (n) |

|---|---|

| Psychological Determinants | |

| Trust (30) | Good provider relationship (24) |

| Value provider recommendation (28) | |

| Have long-term provider relationship (15) | |

| Have personal provider relationship (6) | |

| Model from peer advice and behavior (7) | |

| Interpersonal Determinants | |

| Recommendation/Information (30) | Provider recommendation important (30) |

| Actively seek out provider opinion (3) | |

| Actively seek out peer advice (13) | |

| Actively seek media information (8) | |

| Interpersonal Source Determinants | |

| Physician (30) | Primary physician (27) [Other provider/clinic] (3) |

| Social Network (21) | Friends (14) |

| Work colleagues (13) *could mention more than one | |

| Organizational Source Determinants | |

| Media (13) | Television commercials (4) |

| Social, Facebook (6) {Health websites] (2) [General, including print] (1) | |

| Barriers | |

| Physician | Fear of new vaccine (18) |

| Fear of side effects (20) [Paralysis] (5) [Autism] (5) [Vague symptoms] (10) | |

| Desire for participatory decision culture (12) | |

| Not enough time; “Put on the spot” (14) | |

| Disempowerment (8) | |

| Physician vaccination behavior (5) [For sons] (3) | |

| Social Networks | Family beliefs (7) [Safety] (4) [Efficacy] (2) [Religion] (1) |

| Sexual stigma (12) | |

| Lack of network for young moms (5) | |

| Media | Overload of fear (13) |

| Fatalism (8) | |

| Conflicting information (13) Themes [Subthemes] | |

| [Safety] (13) [Efficacy/protection] (11) |

|

| Lack of male representation (8) | |

| Cues to Action | |

| Provider | Ask for more time for new vaccine (15) [For safety info] (13) [For benefits/protection] (8) |

| Take away power of physician (9) [Take control of your child’s health] (6) | |

| Ask provider for vaccine behavior (5) [For boys] (3) | |

| Social Networks | Look for like-minded vaccination individuals (9) [Work] (6) [Teachers] (3) |

| Shift blame to media | For sexual stigma (7) |

| For misrepresentation of adverse side effects (11) | |

| Media | |

| All mothers | Stop fear (26) |

| Provide accurate safety (22) | |

| Provide accurate protection (17) | |

| Increase representation of males (7) | |

| Hesitant mothers | New vaccine belief (15) |

| Question side effects (11) | |

| Question protective benefits (7) [Questions STDs alone] (3) | |

| Question male applicability (7) |

Table 3.

Example quotes for model components.

| Model Component | Exemplary Quotes |

|---|---|

| Trust in information/recommendation | |

| Provider | “Provider recommended and I’m comfortable with him.” |

| When my provider said let’s get vaccinated (for HPV), I did it.” | |

| “I always did what they (pediatricians) recommended.” | |

| “I have known my physician for a long time. Go to church together, nurse babies with. I trust her.” | |

| “Doctors are the middleman for information.” | |

| “I didn’t think I knew what I need about medicine and vaccinations, so I asked my pediatrician during [child’s] physical exam.” | |

| Social | “At the health department where I work, we are always asking each other as mothers, ‘What did you do’, whether it’s HPV vaccination or breast feeding.” |

| “A lot of what we decide to do is dependent upon what others (in peer network at work) decided to do.” | |

| “One of my sorority sisters asked whether anyone had vaccinated their child for HPV. I chimed in first, stating that my daughter had her first dose and will be getting her second. Others chimed in. We tend to follow each other.” | |

| “I have a good group of friends from college. We all discuss health (and HPV vaccination) and are all prone to getting the vaccine.” | |

| Information Only | |

| Media | “I think it was a commercial, the one where kids ask their parents [Did You Know] that I learned about it (HPV vaccine).” |

| “I did not know it was for boys. I think I saw that from a TV commercial.” | |

| “I see the ads (about vaccination) on TV.” | |

| “I saw that negative information about it (vaccination) on television, I think it was Dateline/2020 about all of the side effects.” | |

| Barriers | |

| Provider | “Provider recommended, but I had some concerns. It was so new.” |

| Provider | “My provider talked to me about it, but I was hesitant at first. I hadn’t had time to think about it.” |

| “I knew about it (HPV vaccine); I just didn’t realize it had come to getting it that day. I was kind of put on the spot, needed to talk about it more.” | |

| “People who see doctors can see them as God like, with all the answers and feel it would be insulting to question them. This is insulting as a mother. You are looking out for your child’s quality of life.” | |

| “My question to my provider was, ‘Did you vaccinate your children?’ When she said yes, I said I am willing to do the same with my children.” | |

| “My physician told me he vaccinated his sons. I thought well, if he did it for his sons, then I certainly should be doing it.” | |

| “We knew it (vaccine) was not going to protect him because at the time, I only thought it was for cervical cancer. So we were looking at it as something that would protect his future partner. Because it was not going to protect him, we made it his decision.” | |

| “I felt it was not as much for him as for his future spouse.” | |

| Social | “We do not vaccinate on schedule. My husband’s mother is a holistic nutritionist and hates vaccination, so we comprise compromise in the middle.” |

| “Holding off (from vaccinating) terrified me, but for the sanctity of my marriage, we did.” | |

| “I question… there’s talk that… not having sex is a lot more effective at preventing more cancer than the three cervical cancers this vaccination prevents.” | |

| “I believe people feel that getting this vaccine is insinuating that kids are going to start having sex.” | |

| “My friend knows someone who developed Autism after the vaccination. She had other health problems. So, it (vaccination) can hurt if health is already compromised.” | |

| Model Component | Exemplary Quotes |

| Media | “When mass media addresses health issues, it is very generalized and fatalistic. It seems the world is so full of risk there is no point in trying.” |

| “It is hard to know what information to trust. The other day I saw something on Facebook saying not to let your children get the HPV vaccine; they can’t walk after and lose muscle tone. It is hard to know the truth.” | |

| “So many things we hear in the media seem fatalistic – everything can cause cancer – you become saturated. So you think that being proactive isn’t going to help; I am going to die of cancer anyway. So, if I have a very busy life, why would I make this (vaccination) a priority?” | |

| “The various claims in the media make it seem that getting the vaccine for your child takes a ‘leap of faith’.” | |

| “I hear a lot of conversation (on social media) that this is no proof the HPV vaccine is helpful and that it is actually more harmful. There are a lot of really strange reactions to the vaccine that are not grounded in reality.” | |

| “Most of the literature and commercials I had seen was addressing cervical cancer, so gender wise, I had not seen as much about boys.” | |

| Cues to Action | |

| Provider | “Give parents time to read about it, get literature about it.” |

| “If physicians provide information about a year before, that helps.” | |

| “They (physician) put the buzz in your ear so it gets you thinking. But I want to research on my own before the next appointment. Ask (your provider) for that opportunity.” | |

| “Don’t feel it is insulting to question your doctor. Say, ‘you are the expert in health care, but I am the expert in my child.’” | |

| Model Component | Exemplary Quotes |

| Social Networks | “Finding someone else who is positive about it (HPV vaccination) is what it is going to take to seal the deal.” |

| “Look for positive people and relay positive messages about HPV.” | |

| [Shifts blame to media] | “I feared that I’d be looked at negatively for encouraging my child to have sex if I permitted the vaccine. We have to deal, via social media, with that sexual stereotype that kids are going to be sexually active if they get the vaccine.” |

| “I believe people feel that getting this vaccine is insinuating that kids are going to start having sex. Message creators have to dispel that ‘you’re not bad, promiscuous, for asking about the vaccine’.” | |

| Media | “I see a lot of contradictory information out there in the media. Media need to let parents know the vaccine is safe.” |

| “A solution (to all the fear in the media) is to show that hey, here is this thing (vaccination), it affects people and prevents something very specific. You want to show a solution so that it doesn’t come across as you are screwed no matter what.” | |

| “Some of the things I am noticing on social media that you are giving your child permission to have sex. If someone said you have a chance to protect from breast cancer or prostate cancer, you would jump on it. Take the sex out of it. Have media messages that tell the cancers it (HPV vaccine) prevents.” | |

| “I had seen reports about adverse side effects. I think the vaccine makes them sexually active. Media need to report facts about adverse side effects.” | |

| “[retracted male son] turned 14 in July, and pediatrician said he is due the vaccine. I thought it was only for girls. More media messages about boys is needed.” | |

| “Mass media need to talk about this (HPV vaccine) about boys. I wasn’t thinking about protection from cancer (when I first heard about vaccine). I was thinking it was protection for sexually transmitted diseases, and boys can be carriers of that?” | |

| “The vaccine is so new for boys. Media need to tell about the statistics on adverse effects, especially for boys.” |

3.2.1. Socio-ecological Determinants: Trust and accurate information from interpersonal and organizational sources

Information and trust in the information were the attributes most important to mothers’ vaccination decision. Mothers looked to physicians or other health workers, followed by peers in social networks, and the media for trusted information. Provider recommendation was important to all mothers, and trust in provider recommendation was described by nearly all as having a good relationship with their health provider that they acquired through long-term patient/provider or personal relationships as well as placing value in provider recommendation, although only a few actively sought out physician recommendation.

Most mothers reported vaccinating immediately upon physician recommendation at a well-child visit. As exemplified, “When my provider said let’s get vaccinated (for HPV), I did it.” Some mothers (n = 5) initially delayed vaccination to research the benefits and barriers on their own before returning for vaccination. Social networks, including friends and peers and colleagues at work, were also mentioned as trusted sources of HPV vaccination information, but with less frequency than providers. Many mothers reported they actively sought information from peers and colleagues, looking for “like-minded” peers in terms of HPV vaccine belief and general health beliefs. Many mothers reported that they were more willing to vaccinate their own child after hearing that peers they trusted had vaccinated theirs. For example:

“One of my sorority sisters asked whether anyone had vaccinated their child for HPV. I chimed in first, stating that my daughter had her first dose and will be getting her second. Others chimed in. We tend to follow each other.”

Less frequently, the media, defined as television commercials, social media, health websites (WebMD), and general print, were named as information sources. Mothers mentioned actively seeking information on social media and health websites, while commercials and print media information were initially passively absorbed.

3.2.2. Barriers to confidence in vaccination decision

Providers (Interpersonal). Although all mothers reported trust in their physician, most mothers recalled feeling hesitant upon vaccinating. Hesitancy and misinformation were intertwined. Of hesitant mothers, their main hesitancy was related to fear, most often related to possible adverse side effects associated with a new vaccine. Hesitant mothers voiced the vaccine did not have enough research behind it to have confidence in provider recommendation. Side effects commonly mentioned were paralysis, Autism and uneasiness over vague, undefined symptoms. Fear of vaccine side effects led a few mothers to delay, but most still accepted with these fears. Mothers who experienced hesitancy, although verbalizing physician trust, largely reported feeling “put on the spot” to decide at the office, which constituted a barrier to a confident decision. As one participant stated, “I knew about it (HPV vaccine); I just didn’t realize it had come to getting it that day. I was kind of put on the spot, needed to talk about it more.” Again, although frustrated and anxious about being put on the spot, most mothers still accepted vaccination but expressed unhappiness with it. Many mothers expected more of an iterative, participatory decision process and wanted to be given time to research benefits/drawbacks and come back for a second conversation. Some mothers, by not being allowed time to explore, expressed feelings of disempowerment, and for one mother, even anger, at being put on the spot to decide. As one participant described of the control mothers should have:

“(You have to) say here is what I see as a parent…You are the expert in healthcare, but I am the expert in my child.”

Five mothers who noted hesitancy and did not have a personal relationship with their physician mentioned needing to know that their physician had or would vaccinate his/her own child in order to feel confident in accepting vaccination. This was especially true of three mothers of sons, who stated or implied confusion over HPV transmission and vaccine efficacy for males. For example: “My physician told me he vaccinated his sons. I thought well, if he did it for his sons, then I certainly should be doing it.”

Social Networks/Interpersonal. Although peers, friends and colleagues were support networks for vaccination, family members (e.g. parents, siblings and relatives) were more often seen as barriers. Some mothers told stories of family members who were opposed to vaccines due to belief in adverse risks, lack of efficacy, or religious reasons. Vocalized opposition from family lead a couple to delay vaccination. Further, while like-minded peers were sought to encourage vaccination, there were still whispers of conversations about HPV sexual stigma and “promiscuity” that were heard outside of their inner circle but re-told in stories within their social network that caused mothers hesitancy and even delay. A third barrier to using social networks for vaccine assurance occurred among younger mothers who did not feel they had a social network of peers to lean on for HPV vaccine advice. Even though most accepted, they lacked confidence in doing so without external support systems.

Media/Organizational. Media (defined as commercials, social and general) were described as information sources for some mothers, but the information was absorbed with more skepticism than provider or peer information. Mothers described three major barriers to developing trust in vaccine acceptance based on media information alone. First, they reported experiencing an overload of fear due to the ubiquitous presence of ads and commercials that correlate cancer and death. The ubiquity of fear caused a fatalistic mindset for some mothers that had them questioning why they should participate in “yet another cancer prevention technique”, given that “everything causes cancer”. Second, mothers reported an overload of conflicting information about safety and efficacy of the vaccine that made it difficult for them to know what to believe. Sources of conflicting media information included social media such as Facebook, but also included print and television advertisements. Third, some mothers reported that initial commercials and advertisements on television focused on vaccination for prevention of cervical cancer and that led to confusion about the efficacy and need for vaccination for males, although many acknowledged they had recently seen more advertisements that include males. All media reasons caused hesitation, but most accepted vaccination, but did so with confusion and concern.

3.2.3. Cues to action

Provider/Interpersonal. Mothers were asked to discuss strategies they believed could help empower other mothers to have stronger confidence for accepting the HPV vaccine for their children. The top strategy recommended was for parents to “ask your provider for more time”. This strategy was voiced from ongoing misperception that the HPV vaccine is still new, and thus mothers should research the vaccine’s safety and benefits, including protection, especially for males, to make an informed decision. Within narratives about requesting more time, several hesitant mothers talked about the general power of physicians and the problem in US culture with seeing physicians as “God-like” and suggested diminishing provider power by taking control of your child’s health. Some mothers also advised that mothers should directly ask their provider whether he/she has or would vaccinate their child, with a few particularly stating the importance of finding out whether or not they would vaccinate a son, reflecting ongoing misperception about transmission of HPV (i.e., that vaccinating males is to protect females) and the benefit of vaccination for males.

Social Networks/Interpersonal. A repetitive suggestion for using social networks to support HPV vaccination decisions was to actively search for like-minded individuals in professional circles with positive HPV vaccination attitudes, primarily found in one’s place of work and among a child’s teachers. However, many mothers’ narratives continued to convey that gossip within their circles continued, primarily about 1) stories of adverse side effects, especially related to Autism and paralysis and 2) sexual stigma/promiscuity that caused continued hesitancy. No strategy for individuals within social networks was offered to counter stigma or misleading side effects. Instead, responsibility for transference of stigma and misinformation and strategies for combatting it were placed with media as an institution.

Media/Organizational. Hesitant mothers’ narratives about strategies for empowering others to vaccinate regularly mentioned that the media induced fear about HPV vaccination. Media culpability came from both initially hesitant and non-hesitant mothers. Mothers relayed that the media are responsible for stopping the fear, and to do so, the media should 1) provide accurate statistics on safety and adverse side effects, 2) provide information about vaccine benefits (protection) and 3) assure the use of males in HPV commercials that air in the daytime. Hesitant mothers’ suggestions for doing so, however, continued to be couched in misperceptions and hesitancy surrounding concerns with safety of a “new vaccine”. They displayed confusion when talking about contradictory side effects read about in the media and when talking about what the vaccine prevents, with a few questioning whether the vaccine primarily protects from STDs. For instance, “I had seen reports about adverse side effects. I think the vaccine makes them sexually active. Media need to report facts about adverse side effects.”

Recommendations for including more males in HPV vaccine commercials also reflected continued confusion about the applicability of the vaccine for males. No recommendation included policy changes to enact media guidelines for HPV vaccination reporting.

4. Discussion

Despite nearly 14 years since the HPV vaccine was licensed, results indicate ongoing concern with HPV vaccination, even among vaccine “accepting” parents. The study found that trust and accurate information were perceived as necessary to mothers’ decisions to vaccinate. The social-ecological model and HBM constructs of barriers were useful for identifying that the primary sources for trust and information were those related to interpersonal and organizational levels: providers, social networks and the media. It also showed that barriers to obtaining and maintaining trusted information existed from these social-ecological sources.

Mothers’ recommendation for taking control and requesting time to research vaccination benefits and safety is of particular concern because it runs counter to the consensus stance that providers make presumptive, strong, and bundled recommendations for HPV vaccination (Miles and Huberman, 1994). Systematic reviews suggest that greater trust in providers is associated with higher likelihood of vaccine acceptance (Attia et al., 2018, Smith et al., 2017, Yeung et al., 2016). These mothers reported trust in provider recommendation, but their narratives expressed an undermining of trust. Mothers expressed doubts, frustration and anger over physician recommendation to vaccinate “on the spot” that continued in their suggestions for mothers to delay vaccination to research vaccine benefits and safety. The Internet has created a new way to put the patient at the center of medicine (Brown et al., 2010). Patients are pushing for bigger roles in decisions about their health (Brown et al., 2010), yet there are no viable alternative treatments for protecting against HPV-related cancers for parents to weigh other than receiving the HPV vaccination. To reach the Healthy People 2020 goal of 80% series completion, physicians must be trusted. As patients have better access to health information through the Internet and expect to be more engaged in health decision-making, traditional models of the patient-provider relationship and communication strategies need revisited to adapt to the information-seeking age (Horgan et al., 2017). Providers can discuss upcoming plans to administer the HPV vaccine during a prior office visit, which would respect mothers’ desires for information but not undermine the bundled presumptive recommendation approach. Providers can offer parents ready-made brochures and links to valid and reliable HPV online information at office visits to direct them to credible rather than noncredible sources of information.

Some of the themes of hesitancy and misinformation in mothers’ narratives, including side effects of a “new” vaccine (Tan and Goonawardene, 2017, Brabin et al., 2006, Davis et al., 2004, de Visser and McDonnell, 2008, Gerend et al., 2007, Constantine and Jerman, 2007, Kahn et al., 2009, Ogilvie et al., 2007); lack of awareness and understanding of protective benefits for males (Woodhall et al., 2007, Oldach and Katz, 2012, Nandwani, 2010, Alexander et al., 2012), and concerns with promiscuity and stigma (Brabin et al., 2006, Gerend et al., 2007, Ogilvie et al., 2007, Alexander et al., 2012, Waller et al., 2006) have been evidenced since early licensure. However, that should not be the case 14 years post-licensure. This study suggests that while HPV vaccination policy has been implemented and revised over time, public opinion still lags behind.

Although influential on vaccine attitudes and opinions, the media have not been adequately addressed in the HPV vaccination literature (Nandwani, 2010). This study found that mothers viewed the media at the organizational level as the source of HPV vaccination confusion, misinformation and fear. Even when hesitant mothers acknowledged that confusing posts were disseminated on social media by individuals, they did not blame individuals, but attributed the confusion and misinformation to social media company policies. However, these mothers did not recommend policy strategies or media guidelines for monitoring misinformation. Anti-vaccine groups who prey on fear and dissemination of misinformation are bountiful on social media (Chan et al., 2007). Vigilance and monitoring of social platforms are crucial for effective vaccine public outreach.

4.1. Limitations

The study has limitations to acknowledge. Although a sample size of 30 interviews was adequate for the design, it limits the generalizability of findings. Mothers were educated, with many coming from a pediatric medical department, and 60% within the healthcare industry. While their perspective allowed for articulation of detailed insight for explaining the decision-making processes, mothers without healthcare backgrounds and of lesser education may have different perspectives and should be studied for comparison.

5. Conclusions

Many mothers who have accepted HPV vaccination continue to perceive the vaccine as new, and are confused, uninformed and mistrusting of the vaccine and believe other mothers are also. Findings have implications for understanding parental decisions about follow-up doses and vaccinating other children. Specifically, parents who continue to carry hesitancy and misinformation may make recommendations that could mislead other parents, or result in refusal of their child’s follow-up doses for series completion or delay or refusal for a younger child upon reaching vaccination age. Therefore, mothers who have accepted the HPV vaccine may still need additional strengthening of individual attitudes, knowledge and reinforcement of provider trust. Results can also be informative for encouraging providers to think about altering their vaccination messaging, especially for setting up patients with credible, timely information sources and involving their personal stories, beliefs and behaviors about HPV vaccination.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of South Florida Nexus Initiative Grant. The sponsor had not role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Kimberly K Walker, Email: walkerk1@usf.edu.

Heather Owens, Email: howens2@usf.edu.

Gregory Zimet, Email: gzimet@iu.edu.

Appendix A. . Interview questions

General Questions

Was your child vaccinated for HPV?

Where was your child vaccinated for HPV?

Where did you first hear about the HPV vaccine?

Was the first time you heard about the HPV vaccine from your provider or elsewhere, describe?

Did your provider recommend the HPV vaccine?

Did you accept the vaccine for your child at the point of recommendation?

How sure were you about your decision to vaccinate?

Probing Questions

What had you heard about the HPV vaccine prior to doctor recommendation, if any?

What were your concerns about the vaccine prior or at recommendation?

Where did those concerns originate?

Describe your experience with the HPV vaccine decision and any challenges/thoughts when deciding about accepting.

What would you recommend to help other parents make the decision to accept HPV vaccination based upon your experience?

References

- A.B. Alexander, N.W. Stupiansky, M.A. Ott, D. Herbenick, M. Reece, G.D. Zimet. What parents and their adolescent sons suggest for male HPV vaccine messaging, Health Psychol 33(5) (2014) 448-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Alexander A.B., Stupiansky N.W., Ott M.A., Herbenick D., Reece M., Zimet G.D. Parent-son decision-making about human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander A.B., Best C., Stupiansky N., Zimet G.D. A model of health care provider decision making about HPV vaccination in adolescent males. Vaccine. 2015;33(33):4081–4086. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2019. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2019/cancer-facts-and-figures-2019.pdf.

- Attia A.C., Wolf J., Nunez A.E. On surmounting the barriers to HPV vaccination: we can do better. Ann. Med. 2018;50(3):209–225. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2018.1426875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L. Brabin, S.A. Roberts, F. Farzaneh, H.C. Kitchener. Future acceptance of adolescent human papillomavirus vaccination: a survey of parental attitudes, Vaccine 24(16) (2006) 3087-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brown K.F., Kroll J.S., Hudson M.J. Factors underlying parental decisions about combination childhood vaccinations including MMR: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2010;28(26):4235–4248. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.04.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L. Caperon, A. Arjyal, Puja, K.C., J. Kuikel, J. Newell, R. Peters, A. Prestwich, R. King. Developing a socio-ecological model of dietary behaviour for people living with diabetes or high blood glucose levels in urban Nepal: a qualitative investigation, PLoS One 14(3) (2019) e0214142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chan S.S.C., Cheung T.H., Lo W.K., Chung T.K.H. Women’s attitudes on human papillomavirus vaccination to their daughters. J. Adolescent Health. 2007;41(2):204–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A.B. Coe, S. Gatewood, L.R. Moczygemba, J. Goode, J Beckner. The use of the health belief model to assess predictors of intent to receive the novel (2009) H1N1 influenza vaccine, Innov Pharm 3(2) (2012) 1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Constantine N.A., Jerman P. Acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccination among Californian parents of daughters: a representative statewide analysis. J. Adolesc. Health. 2007;40(2):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- County Health Rankings. Indiana. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/app/indiana/2020/rankings/marion/county/outcomes/overall/snapshot.

- K. Davis, E.D. Dickman, D. Ferris, J.K. Dias. Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among parents of 10- to 15-year-old adolescents, J Low Genit Tract Dis 8(3) (2004) 188-94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- de Visser R., McDonnell E. Correlates of parents' reports of acceptability of human papilloma virus vaccination for their school-aged children. Sex. Health. 2008;5(4):331. doi: 10.1071/SH08042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facciola A., Visalli G., Orlando A. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview on parents' opinions about vaccination and possible reasons of vaccine refusal. J. Public Health Res. 2019;8(1):1436. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2019.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L.Y. Fu, G. D. Zimet, C. A. Latkin, J. G. Joseph. Social Networks for Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Advice Among African American Parents, J Adolesc Health 65(1) (2019) 124-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gerend M.A., Lee S.C., Shepherd J.E. Predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination acceptability among underserved women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2007;34(7):468–471. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000245915.38315.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G., MacQueen K.M., Namey E.E. Applied Thematic Analysis. Sage Publications Inc; 2012. Introduction to Applied Thematic Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Harper C.R., Steiner R.J., Brookmeyer K.A. Using the social-ecological model to improve access to care for adolescents and young adults. J. Adolescent Health. 2018;62(6):641–642. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix K.S., Sturm L.A., Zimet G.D., Meslin E.M. Ethics and Childhood Vaccination Policy in the United States. Am. J. Public Health. 2016;106(2):273–278. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman D.M., Benard V., Roland K.B., Watson M., Liddon N., Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(1):76–82. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan D., Henning G., Banks I., van der Wal T., Hasurdjiev S., Pelouchova J. For the many, not the few: patient empowerment. Biomed. Hub. 2017;2(Suppl 1):37–40. doi: 10.1159/000481128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A. Hoss, B.E. Meyerson, G.D. Zimet. State statutes and regulations related to human papillomavirus vaccination [published correction appears in Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019 Aug 2;:1], Hum Vaccin Immunother 15(7-8) (2019) 1519-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hussain A., Ali S., Ahmed M., Hussain S. The anti-vaccination movement: a regression in modern medicine. Cureus. 2018;10(7) doi: 10.7759/cureus.2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N.F., Velásquez N., Restrepo N.J., Leahy R., Gabriel N., El Oud S., Zheng M., Manrique P., Wuchty S., Lupu Y. The online competition between pro- and anti-vaccination views. Nature. 2020;582(7811):230–233. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn J.A., Ding L., Huang B., Zimet G.D., Rosenthal S.L., Frazier A.L. Mothers' intention for their daughters and themselves to receive the human papillomavirus vaccine: a national study of nurses. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1439–1445. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L.M. Kester, G.D. Zimet, J.D. Fortenberry J.A. Kahn, M.L. Shew. A national study of HPV vaccination of adolescent girls: rates, predictors, and reasons for non-vaccination, Matern Child Health J 17(5) (2013) 879-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leask J., Kinnersley P., Jackson C., Cheater F., Bedford H., Rowles G. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- L.A. Marlow, G.D. Zimet, K.J. McCaffery, R. Ostini, J. Waller. Knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) and HPV vaccination: an international comparison, Vaccine 31(5) (2013) 763-69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meites E., Szilagyi P.G., Chesson H.W., Unger E.R., Romero J.R., Markowitz L.E. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019;68(32):698–702. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M.B., Huberman A.M. second ed. Sage Publications Inc; 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. [Google Scholar]

- Nandwani M.C. Men's knowledge of the human papillomavirus vaccine. Nurse Pract. 2010;35(11):32–39. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000388900.49604.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman P.A., Logie C.H., Lacombe-Duncan A., Baiden P., Tepjan S., Rubincam C., Doukas N., Asey F. Parents’ uptake of human papillomavirus vaccines for their children: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e019206. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019206.supp2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogilvie G.S., Remple V.P., Marra F., McNeil S.A., Naus M., Pielak K.L., Ehlen T.G., Dobson S.R., Money D.M., Patrick D.M. Parental intention to have daughters receive the human papillomavirus vaccine. Canad. Med. Assoc. J. 2007;177(12):1506–1512. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldach B.R., Katz M.L. Ohio Appalachia public health department personnel: human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine availability, and acceptance and concerns among parents of male and female adolescents. J. Community Health. 2012;237(6):1157–1163. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9613-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C.A. Panozzo, K.J. Head, M.L. Kornides, K.A. Feemster, G.D. Zimet. Tailored messages addressing human papillomavirus vaccination concerns improves behavioral intent among mothers: a randomized controlled trial, J Adolesc Health (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- Senkomago V., Henley S.J., Thomas C.C., Mix J.M., Markowitz L.E., Saraiya M. Human Papillomavirus–Attributable Cancers — United States, 2012–2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019;68(33):724–728. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L.E., Amlôt R., Weinman J., Yiend J., Rubin G.J. A systematic review of factors affecting vaccine uptake in young children. Vaccine. 2017;35(45):6059–6069. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- S.S. Tan, N. Goonawardene. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review, J Med Internet Res 19(1) (2017) e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- J. L. Taylor, G.D. Zimet, K.L. Donahue, A.B. Alexander, M.L. Shew, N.W. Stupiansky. Vaccinating sons against HPV: results from a U.S. national survey of parents, PLoS One 9(12) (2014) e115154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-andinfectious- diseases/objectives.

- Walker T.Y., Elam-Evans L.D., Yankey D., Markowitz L.E., Williams C.L., Fredua B., Singleton J.A., Stokley S. National, Regional, State, and Selected Local Area Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 13–17 Years — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2019;68(33):718–723. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller J., Marlow L.A., Wardle J. Mothers' attitudes towards preventing cervical cancer through human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(7):1257–1261. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhall S.C., Lehtinen M., Verho T., Huhtala H., Hokkanen M., Kosunen E. Anticipated acceptance of HPV vaccination at the baseline of implementation: a survey of parental and adolescent knowledge and attitudes in Finland. J. Adolesc. Health. 2007;40(5):466–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung M.P., Lam F.L., Coker R. Factors associated with the uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination in adults: a systematic review. J. Public Health (Oxf) 2016;38(4):746–753. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]