Abstract

This observational study assesses the association of a new trauma center with transport times for trauma patients as a measure of prompt access to care and specifically examines changes in racial, ethnic, and income disparities in transport times.

There are significant racial disparities in access to trauma care in the United States.1 On May 1, 2018, the University of Chicago Medicine opened a level 1 trauma center (University of Chicago Medicine Trauma Center [UCMTC]) on the south side of Chicago, Illinois, an area previously described as a trauma desert because of the lack of trauma centers.2 The area has a predominantly Black population, a significant percentage of households below the federal poverty line, and a high burden of firearm injury.3,4 Here, we analyzed the association of the UCMTC with transport times for trauma patients as a measure of prompt access to care. We specifically examined changes in racial, ethnic, and income disparities in transport times.

Methods

We obtained data for emergency medical services (EMS) runs related to traumatic injury originating in Chicago, Illinois, between May 1, 2017, and April 30, 2019, from the Illinois Department of Public Health. We included patients 16 years or older who were transported to a level 1 or 2 trauma center. Transport time was defined as the interval from scene departure to hospital arrival. We compared transport times by scene zip code, race, ethnicity, and patient zip code income status from the 1-year period prior to the opening of UCMTC to the year following. Race and ethnicity were classified by an EMS paramedic. Zip codes were defined as low income if the median income was below 200% of the federal poverty line for a family of 4.5 The study was approved by the Illinois Department of Public Health and University of Chicago Medicine institutional review board, and patient consent was waived because the research involved minimal risk and individuals were not directly identifiable from the data. Statistical significance was determined using 2-sided t tests, with Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple tests of transport time changes by zip code. Two-sided P values were used with a significance threshold of .05.

Results

There were 27 322 EMS runs included in the study: 12 802 (46.9%) before the opening of UCMTC and 14 520 (53.1%) after. Overall, 13 506 patients (49.8%) were Black, 3958 patients (14.6%) were Hispanic, and 14 579 patients (53.8%) were from low-income zip codes. Prior to the opening, there were significant disparities in transport times between Black and White non-Hispanic patients (mean [SD], 8.9 [6.4] vs 6.9 [4.7] minutes; P < .001), Hispanic and White non-Hispanic patients (mean [SD], 8.6 [6.1] vs 6.9 [4.7] minutes; P < .001), and patients from low-income and not from low-income zip codes (mean [SD], 9 [6.5] vs 7.5 [5.2] minutes; P < .001). Black patients from low-income zip codes had the longest overall transport times (Table).

Table. Emergency Medical Services Transport Time Before and After Opening of the University of Chicago Medicine Trauma Center by Race, Ethnicity, and Neighborhood Poverty Statusa.

| Characteristic | Transport time, mean (SD), min | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Opening | P value | ||

| Before | After | ||

| Black | |||

| Total | 8.9 (6.4) | 7.4 (5.1) | <.001 |

| Low-income zip | |||

| No | 8.3 (5.9) | 6.9 (4.6) | <.001 |

| Yes | 9.2 (6.6) | 7.5 (5.3) | <.001 |

| Hispanic | |||

| Total | 8.6 (6.1) | 8.4 (5.3) | .30 |

| Low-income zip | |||

| No | 8.4 (5.4) | 8.2 (5.2) | .47 |

| Yes | 8.7 (6.8) | 8.5 (5.4) | .47 |

| White non-Hispanic | |||

| Total | 6.9 (4.7) | 7.1 (4.8) | .09 |

| Low-income zip | |||

| No | 6.6 (4.5) | 6.9 (4.7) | .03 |

| Yes | 7.7 (5.3) | 7.5 (5.2) | .48 |

A patient’s home zip code was defined as being a low-income zip code if the zip code’s median annual household income for a family of 4 was below 200% of the federal poverty line in 2018.

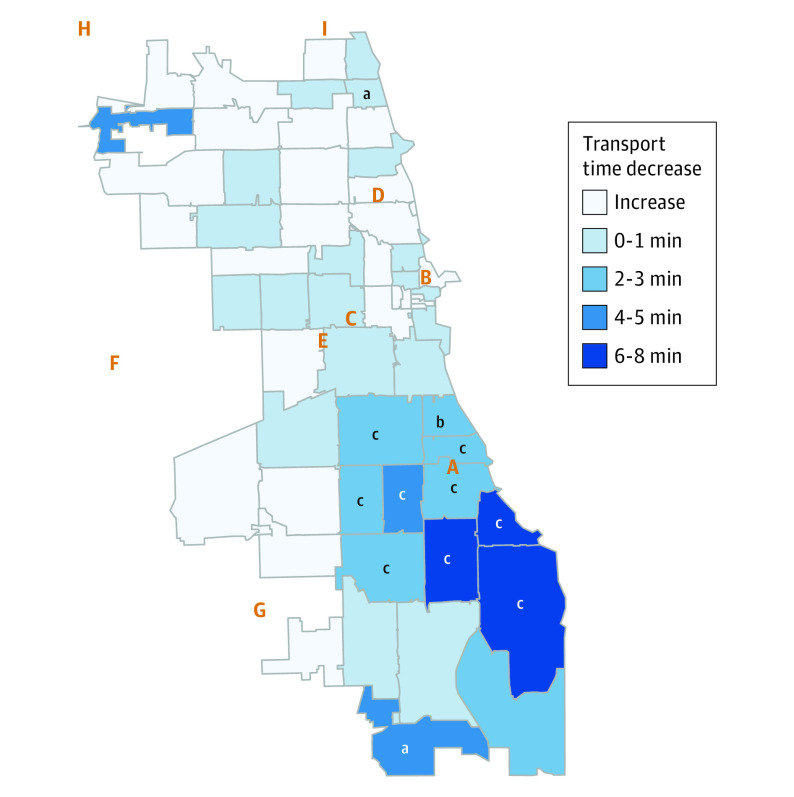

After the opening of UCMTC, the mean (SD) transport time for all runs citywide decreased from 8.3 (5.9) to 7.4 (5.0) minutes (P < .001). The disparity between Black and White non-Hispanic patients was reduced (mean [SD], 7.4 [5.1] vs 7.1 [4.8] minutes; P = .003), with Black patients from low-income zip codes experiencing the largest decrease. The disparity between White non-Hispanic and Hispanic patients remained unchanged (mean [SD], 8.4 [5.3] vs 7.1 [4.8] minutes; P < .001). Zip codes in proximity to UCMTC experienced significant decreases in transport time (Figure). The largest decrease of 8.9 minutes (P < .001) occurred in zip code 60649, a neighborhood where 94% of residents are Black, and the median household income is approximately $30 000.5

Figure. Map of Chicago Zip Codes Showing Reductions in Emergency Medical Services Transport Times.

Reductions in transport times by scene zip code for patients with traumatic injuries in Chicago, Illinois, from the year after opening of the University of Chicago Medicine Trauma Center compared with the year prior to opening. Location of trauma centers is denoted by letters: A, University of Chicago Medicine Trauma Center; B, Northwestern Memorial Hospital; C, John H. Stroger Jr Hospital; D, Advocate Illinois Masonic Hospital; E, Mount Sinai Hospital; F, Loyola University Medical Center; G, Advocate Christ Hospital; H, Advocate Lutheran Hospital; I, St. Francis Hospital.

aBenjamini-Hochberg corrected P < .05.

bBenjamini-Hochberg corrected P < .01.

cBenjamini-Hochberg corrected P < .001.

Discussion

Patterns of residential segregation have given rise to significant racial and ethnic disparities in EMS transport times in Chicago, with poverty concentrating this effect.1 The opening of UCMTC was associated with significant reductions in racial/ethnic disparities in timely access to trauma care for Black patients in Chicago, particularly for Black patients residing in low-income zip codes. Our analysis suggests that disparities in access to trauma care arising from structural racism can be reduced by opening trauma centers in historically underserved areas.4 In Chicago, a 5-minute increase in transport time was associated with a 0.5% decrease in survival among trauma patients in a recent study.6 Therefore, the opening of UCMTC may improve outcomes among patients on the far south side of Chicago, but further research is required to explore the effects of the new trauma center on mortality. Limitations of this study include lack of data on non-EMS transport to trauma centers and data from a single city.

References

- 1.Tung EL, Hampton DA, Kolak M, Rogers SO, Yang JP, Peek ME. Race/ethnicity and geographic access to urban trauma care. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190138. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crandall M, Sharp D, Unger E, et al. Trauma deserts: distance from a trauma center, transport times, and mortality from gunshot wounds in Chicago. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(6):1103-1109. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapustin M, Ludwig J, Punkay M, Smith K, Speigel L, Welgus D. Gun Violence in Chicago, 2016. UChicago Urban Labs Crime Lab. Published January 2017. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/3/1161/files/2018/07/UChicagoCrimeLab-Gun-Violence-in-Chicago-2016-v2-1e4v1n9.pdf

- 4.Boyd RW, Lindo EG, Weeks LD, McLemore MR On racism: a new standard for publishing on racial health inequities. Health Affairs Blog Published July 2, 2020. Accessed October 22, 2020. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200630.939347/full/

- 5.United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS). Accessed October 22, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

- 6.Karrison TG, Philip Schumm L, Kocherginsky M, Thisted R, Dirschl DR, Rogers S. Effects of driving distance and transport time on mortality among level I and II traumas occurring in a metropolitan area. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;85(4):756-765. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000002041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]