Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

To explore the opinion of the Dutch general public and of physicians regarding euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia.

DESIGN

A cross‐sectional survey.

SETTING

The Netherlands.

PARTICIPANTS

Random samples of 1,965 citizens (response = 1,965/2,641 [75%]) and 1,147 physicians (response = 1,147/2,232 [51%]).

MEASUREMENTS

The general public was asked to what extent they agreed with the statement “I think that people with dementia should be eligible for euthanasia, even if they no longer understand what is happening (if they have previously asked for it).” Physicians were asked whether they were of the opinion that performing euthanasia is conceivable in patients with advanced dementia, on the basis of a written advance directive, in the absence of severe comorbidities. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to identify factors associated with the acceptance of euthanasia.

RESULTS

A total of 60% of the general public agreed that people with advanced dementia should be eligible for euthanasia. Factors associated with a positive attitude toward euthanasia were being female, age between 40 and 69 years, and higher educational level. Considering religion important was associated with lower acceptance. The percentage of physicians who considered it acceptable to perform euthanasia in people with advanced dementia was 24% for general practitioners, 23% for clinical specialists, and 8% for nursing home physicians. Having ever performed euthanasia before was positively associated with physicians considering euthanasia conceivable. Being female, having religious beliefs, and being a nursing home physician were negatively associated with regarding performing euthanasia as conceivable.

CONCLUSION

There is a discrepancy between public acceptance of euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia and physicians' conceivability of performing euthanasia in these patients. This discrepancy may cause tensions in daily practice because patients' and families' expectations may not be met. It urges patients, families, and physicians to discuss mutual expectations in these complex situations in a comprehensive and timely manner. J Am Geriatr Soc 68:2319–2328, 2020.

Keywords: dementia, euthanasia, decision making, public opinion, cross‐sectional studies

In the Netherlands, euthanasia and physician‐assisted suicide are allowed if physicians adhere to legal criteria of due care. Euthanasia is defined as the administering of lethal drugs by a physician with the explicit intention to end a patient's life on the patient's explicit request. In physician‐assisted suicide, the patient self‐administers medication that was prescribed intentionally by a physician. Criteria for due care are described in the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (review procedures) Act that came into effect in 2002. 1 These criteria require that the physician must be convinced that (1) the patient's request is voluntary and well considered, (2) the patient is suffering unbearably without prospect of relief, (3) the patient is informed about their situation and prospects, (4) no reasonable alternatives are available to relieve suffering, (5) at least one independent physician must be consulted and give a written statement containing their judgment on the four previous requirements, and (6) euthanasia or physician‐assisted suicide is performed with due medical care and attention. The act does not entail a legal right to euthanasia. Nor does it contain a limit on a patient's life expectancy. Physicians are obliged to report euthanasia to one of five regional review committees. These review committees assess afterward whether or not the physician has acted in accordance with the criteria of due care.

The act does not mention restrictions relating to the cause of suffering. Nor does it differentiate between psychological and other types of suffering. However, most patients who receive euthanasia are suffering from somatic diseases such as cancer. 2 , 3 Only a small proportion of patients who request euthanasia have psychiatric disorders (11%), an accumulation of health problems (8%), or early‐stage dementia (2%). 4 The number of patients with dementia receiving euthanasia gradually increased from 12 patients in 2009 to 146 patients in 2018. In almost all cases it concerned patients with early‐stage dementia, defined as a phase of dementia in which patients still have insight into (the symptoms of) their illness, such as loss of orientation and personality. Patients were deemed competent regarding their request because they could still oversee the consequences of their request. 5 , 6

Euthanasia is widely accepted by the Dutch general public and by physicians. In 2015, 67% of the general public was of the opinion that every person should have the right to euthanasia if they want. 3 Studies show that 50% to 60% of Dutch physicians have ever performed euthanasia, and 25% to 35% of Dutch physicians consider it conceivable, meaning they may consider performing it themselves. 3 However, the performance of euthanasia in patients with dementia, especially in patients with advanced dementia who are no longer competent, is controversial. 7 In 2018, the Dutch Public Prosecution Service for the first time since the introduction of the Act on Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide in 2002 initiated a legal investigation of a physician who had performed euthanasia in a 74‐year‐old demented and incapacitated woman. The regional review committees had concluded that this physician had not complied with the legal due care criteria because the written euthanasia request of the patient was not sufficiently clear and the patient seemed to resist the actual act. In September 2019, the court acquitted the nursing home physician. In April 2020, the Supreme Court confirmed this verdict.

In general, the debate on euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia mainly focuses on issues related to the criteria of due care. The first issue is whether it is possible for the physician to assess whether a patient with advanced dementia is suffering unbearably because the possibility of having meaningful communication is impaired. 8 , 9 A second topic of debate is whether physicians should be allowed to perform euthanasia based on an advance directive that was written at the time the patient was still competent. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 The act states that a physician can respond to a written euthanasia request, although they are never obliged to do so; nor are they obliged to refer a patient. 11 , 15 Physicians may encounter the dilemma of how to appreciate current wishes of the person with dementia when their advance directive holds opposing wishes. 11 This may raise questions about the validity of advance directives in patients with advanced dementia.

The aim of this study was to explore the opinion of the general public and of physicians regarding euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia who are incompetent to consent to care and to study factors associated with the acceptance of euthanasia in patients with dementia. Insight in the support for this practice among the general public and physicians can help inform the debate.

These were our research questions:

‐ To what extent does the general public consider euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia acceptable?

‐ To what extent do physicians consider performing euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia conceivable?

‐ Which demographic and health or professional characteristics are associated with positive attitudes toward euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia?

METHODS

Design and Participants

A cross‐sectional study was performed among a random sample of the general public and physicians in the Netherlands. The study was conducted as part of the third evaluation of the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide (review procedures) Act. Data were collected between May and September 2016. Because this study did not impose any interventions or actions, and no patients were involved, it did not require approval by a research ethics committee. 16

General Public

An online questionnaire was distributed among members of the CentERpanel. This panel comprises 2,641 households that were randomly selected from the pool of national postal delivery addresses. 17 All members aged 17 years or older were invited to complete an online questionnaire. Demographic characteristics were provided by the CentERpanel board.

Physicians

A random sample of 2,500 physicians (1,100 general practitioners, 400 nursing home physicians, and 1,000 clinical specialists) were invited to complete a written 12‐page questionnaire. Inclusion criteria for physicians were (1) having been working in adult patient care in the Netherlands for the past year, and (2) having a registered work or home address in the national databank of registered physicians (IMS Health). Overall, 268 physicians did not meet the criteria.

Questionnaires

General Public

Acceptance of euthanasia in case of advanced dementia was operationalized as the level of agreement with the statement “I am of the opinion that patients with dementia should be eligible for euthanasia even if they no longer understand what is happening (if they have previously asked for it).” Answers ranged from 1 (completely agree) to 5 (completely disagree). Other questions concerned the respondents' health status (perceived general health, presence of dementia) and euthanasia‐related characteristics (experience with a relative requesting for euthanasia, opinion about the law, and knowing whether a written euthanasia request is required for patients with advanced dementia to be eligible for euthanasia).

Furthermore, respondents were presented with this vignette about a patient with advanced dementia: Mr. Smit is 62 years old and demented. He no longer recognizes his wife and children, refuses to eat, and withdraws more and more. There is no longer any communication with him about his treatment. Shortly before he became demented, he had a written euthanasia statement drawn up in which he stated that his life must be ended if he would become demented. The family agrees. The physician decides to do what Mr. Smit has asked and performs euthanasia. Respondents were asked two questions about the vignette: “Do you agree with the physician's act?“ and “In this situation, would you yourself complete an advance directive for euthanasia?”

Physicians

Physicians were asked whether they were of the opinion that performing euthanasia is conceivable in (1) early‐stage dementia, in a competent person; (2) advanced dementia, on the basis of a written euthanasia request, in the presence of severe comorbidities; and (3) advanced dementia, on the basis of a written euthanasia request, in the absence of severe comorbidities. Other questions concerned the respondents' demographics (age, sex, religious beliefs) and professional characteristics such as specialty, years of experience, being a palliative care consultant, being trained as an independent advisor for the euthanasia procedure (SCEN physician), ever having received/granted a euthanasia request, either or not from patients with dementia.

Statistical Analysis

Univariable logistic regression analyses were performed to analyze which factors were associated with the public acceptance and physicians considering euthanasia conceivable. The statement “I am of the opinion that patients with dementia should be eligible for euthanasia even if they no longer understand what is happening (if they have previously asked for it)” was used to assess acceptance of euthanasia in the general public. A 5‐point Likert scale was dichotomized into acceptable (agree or completely agree) and not acceptable or neutral (disagree, completely disagree, and neutral). Conceivability of performing euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia by physicians was assessed based on the answer regarding the statement “Euthanasia is conceivable in patients with advanced dementia, on the basis of a written euthanasia request, in the absence of severe comorbidities.” The analysis was based on the statement in which the patient has no severe comorbidities because this situation is likely to be the most controversial, since the absence of severe comorbidities excludes suffering from these comorbidities. Furthermore, this statement is comparable with the statement presented to the general public.

Stepwise backward selection (removal at P > .10) was performed to identify variables associated with public acceptance and physicians considering euthanasia conceivable. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Data were analyzed using SPSS software v.24.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the General Public and Physicians

A total of 1,965 members of the CentERpanel responded to the questionnaire (Table 1). Of the respondents, 49.5% were female, and 20.7% were older than 70 years. Most (97.7%) had a Dutch background, and 19.2% considered their religious faith important. Overall, 76.4% of the respondents thought it is right that there is a euthanasia law and thought they might request euthanasia themselves. Half of the respondents knew that for patients with advanced dementia, a written euthanasia request is required to be eligible for euthanasia.

Table 1.

Background Characteristics of Members of the General Public Who Responded to the Online Survey (n = 1,965) a

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 992 | 50.5 |

| Female | 973 | 49.5 |

| Age, y | ||

| 16–39 | 414 | 21.1 |

| 40–69 | 1,144 | 58.2 |

| ≥70 | 407 | 20.7 |

| Composition of household | ||

| Living with partner | 1,446 | 73.6 |

| Living without partner | 519 | 26.4 |

| Education b | ||

| Low | 552 | 28.1 |

| Middle | 636 | 32.4 |

| High | 777 | 39.5 |

| Background | ||

| Dutch | 1,897 | 97.7 |

| Non‐Dutch | 45 | 2.3 |

| Adheres to religious/philosophical life stance | ||

| Yes | 954 | 49.2 |

| No | 984 | 50.8 |

| Considers religion important | ||

| Yes | 378 | 19.2 |

| No | 1,587 | 80.8 |

| Level of urbanization | ||

| Low | 759 | 39.0 |

| Moderate | 402 | 20.7 |

| High | 783 | 40.3 |

| Health status | ||

| General health | ||

| (Very) good | 1,626 | 82.7 |

| Moderate to (very) bad | 339 | 17.3 |

| Diagnosis of dementia | ||

| Yes | 3 | .2 |

| No | 1,962 | 99.8 |

| Characteristics related to euthanasia | ||

| Experience: Close relative has requested a physician for euthanasia | ||

| Yes | 657 | 33.5 |

| No | 1,305 | 66.5 |

| Opinion: Do you think it is right that there is a euthanasia law? | ||

| Yes, I think I could request euthanasia | 1,498 | 76.4 |

| Yes, but I would never request euthanasia myself | 241 | 12.3 |

| No, I do not think it is right to have this law | 14 | 0.7 |

| No, I am opposed to euthanasia | 99 | 5.0 |

| Do not know | 110 | 5.6 |

| For patients with advanced dementia, a written euthanasia request is required to be eligible for euthanasia. | ||

| Agree | 1,024 | 52.1 |

| Disagree | 367 | 18.7 |

| Do not know | 574 | 29.2 |

The number of missing varied between 0 and 27 (1.4%).

Low: primary education, prevocational secondary (VMBO), the lower years of senior general (HAVO) or pre‐university (VWO) education, or lower level secondary vocational education (MBO‐1). Middle: secondary education diplomas at vocational (MBO 2, 3 or 4), senior general (HAVO) or pre‐university (VWO) level.High: higher (HBO) or university education (WO).

Table 2 lists the background characteristics of the physicians. Of the general practitioners, 3.2% had received a euthanasia request from a patient with dementia in the past year. For nursing home physicians and clinical specialists, the percentages were 5.4% and .9%, respectively.

Table 2.

Background Characteristics of Physicians (n = 1,147) a

| General practitioners | Nursing home physicians | Clinical specialists | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 607 | N = 209 | N = 331 | |

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Demographics | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 260 (43.3) | 80 (38.5) | 198 (60.0) |

| Female | 341 (56.7) | 128 (61.5) | 132 (40.0) |

| Age, y | |||

| <40 | 167 (27.5) | 28 (13.4) | 88 (26.6) |

| 40–54 | 280 (46.1) | 105 (50.2) | 176 (53.2) |

| ≥55 | 160 (26.4) | 76 (36.4) | 67 (20.2) |

| Religious belief | |||

| No | 398 (66.6) | 130 (62.5) | 241 (73.7) |

| Yes | 200 (33.4) | 78 (37.5) | 86 (26.3) |

| Professional characteristics | |||

| Experience, y | |||

| <10 | 142 (23.4) | 22 (10.5) | 65 (19.6) |

| ≥10 | 465 (76.6) | 187 (89.5) | 266 (80.4) |

| Palliative care education | |||

| No | 261 (43.6) | 76 (36.9) | 257 (77.9) |

| Yes | 338 (56.4) | 130 (63.1) | 73 (22.1) |

| Consultant palliative care/Member palliative care team | |||

| No | 597 (98.5) | 181 (87.9) | 308 (93.9) |

| Yes | 9 (1.5) | 25 (12.1) | 20 (6.1) |

| SCEN physician b | |||

| No | 580 (95.7) | 194 (94.2) | 325 (99.1) |

| Yes | 26 (4.3) | 12 (5.8) | 3 (.9) |

| Ever received an explicit euthanasia request | |||

| No | 42 (6.9) | 49 (23.4) | 182 (55.2) |

| Yes but never performed euthanasia | 92 (15.2) | 60 (28.7) | 73 (22.1) |

| Yes and ever performed euthanasia | 472 (77.9) | 100 (47.8) | 75 (22.7) |

| Received a euthanasia request from a patient with dementia in the past year | |||

| No | 572 (96.8%) | 194 (94.6%) | 324 (99.1%) |

| Yes | 19 (3.2%) | 11 (5.4%) | 3 (.9%) |

| Performed euthanasia in a patient with dementia in the last year | |||

| No | 587 (99.3%) | 201 (98.5%) | 327 (100.0%) |

| Yes | 4 (.7%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0 (.0%) |

The number of missing varied between 2 (.2%) and 25 (2.2%).

Independent advisor for the euthanasia procedure.

Of the general practitioners .7% had performed euthanasia in a patient with dementia in the last year. For nursing home physicians, this percentage was 1.5% and for clinical specialists, .0%.

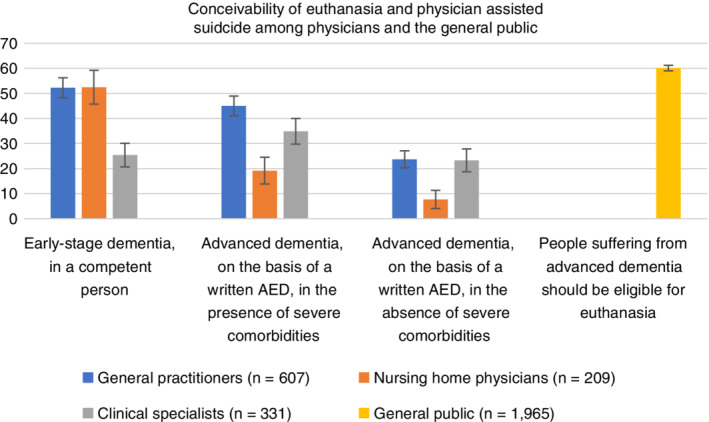

Acceptability and Conceivability of Euthanasia in People with Advanced Dementia

A total of 60% of the general public agreed that people with advanced dementia should be eligible for euthanasia (Figure 1), 24% were neutral, and 27% (completely) disagreed. When respondents were presented the vignette about a patient with advanced dementia with an advance directive for euthanasia and the physician performs euthanasia, 83% of the respondents agreed with the physician's act, and 57% would complete an advance directive for euthanasia themselves if they were in the same situation. About half of the general practitioners and nursing home physicians found euthanasia conceivable in competent persons with early‐stage dementia. Conceivability was lowest for performing euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia on the basis of a written advance directive, in the absence of severe comorbidities: 24% for general practitioners, 23% for clinical specialists, and 8% for nursing home physicians (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceivability of euthanasia and physician‐assisted suicide among physiciansa and the general public. aPhysicians who had ever performed euthanasia were considered to regard euthanasia as conceivable, and they were included in the group who consider euthanasia conceivable. AED, advance euthanasia directive.

Factors Associated with Public Acceptance of Euthanasia in Case of Advanced Dementia

Sex, age between 16 and 39 and age between 40 and 69 years, middle and high educational level, having a Dutch background, and considering their religion important were significantly associated with the public acceptance of euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia (Table 3). In multivariable analyses, factors associated with a positive attitude toward euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia were being female (OR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.11–1.64), age between 40 and 69 (OR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.00–1.64), and higher educational level (OR = 1.53; 95% CI = 1.20–1.95). Considering their religion important was associated with lower acceptance (OR = .23; 95% CI = .18–.29) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics Associated with the General Public's Acceptance of Euthanasia in Case of a Patient with Advanced Dementia (n = 1,949) a

| Absolute | Euthanasia acceptable | Univariable | Multivariable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| numbers | % | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 985 | 56.9 | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 964 | 63.4 | 1.31 (1.10–1.58) | 1.35 (1.11–1.64) |

| Age, y | ||||

| 16–39 | 409 | 60.4 | 1.43 (1.08–1.89) | .96 (.70–1.31) |

| 40–69 | 1,137 | 63.0 | 1.59 (1.27–2.01) | 1.28 (1.00–1.64) |

| ≥70 | 403 | 51.6 | Reference | Reference |

| Living with partner | ||||

| No | 511 | 59.3 | Reference | — |

| Yes | 1,438 | 60.4 | 1.05 (.85–1.28) | |

| Education level b | ||||

| Low | 551 | 54.3 | Reference | Reference |

| Middle | 625 | 60.0 | 1.26 (1.00–1.59) | 1.26 (.98–1.61) |

| High | 773 | 64.3 | 1.52 (1.21–1.90) | 1.53 (1.20–1.95) |

| Background | ||||

| Non‐Dutch | 45 | 44.4 | Reference | Reference |

| Dutch | 1897 | 60.4 | 1.90 (1.05–3.45) | 1.81 (.96–3.42) |

| Considers religion important | ||||

| No | 1,571 | 67.1 | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 378 | 31.0 | .22 (.17–.28) | .23 (.18–.29) |

| Urbanization level | ||||

| Low | 752 | 61.3 | Reference | — |

| Middle | 400 | 56.5 | .82 (.64–1.05) | |

| High | 776 | 60.6 | .97 (.79–1.19) | |

| General health | ||||

| Less than good | 334 | 60.2 | Reference | — |

| (Very) good | 1,615 | 60.1 | 1.00 (.78–1.27) | |

| Presence of dementia | ||||

| No | 1962 | 60.2 | Reference | — |

| Yes | 3 | .0 | .00 (.00‐) | |

Note: Long dash indicates the item was entered in the regression but was eliminated in the stepwise procedure because P > .10. Statistically significant effects are in boldface type. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

The number of missing varied between 0 and 37 (1.9%).

Low: primary education, prevocational secondary (VMBO), the lower years of senior general (HAVO) or pre‐university (VWO) education, or lower level secondary vocational education (MBO‐1).Middle: secondary education diplomas at vocational (MBO 2, 3 or 4), senior general (HAVO) or pre‐university (VWO) level. High: higher (HBO) or university education (WO).

Factors Associated with Physicians Considering Performing Euthanasia Conceivable in Patients with Advanced Dementia

Religious beliefs, sex, specialty, and having ever received a euthanasia request and ever having performed euthanasia were significantly associated with considering performing euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia conceivable by physicians. In multivariable analysis, having ever performed euthanasia before was positively associated with physicians considering euthanasia conceivable (OR = 1.94; 95% CI = 1.21–3.12). Being female (OR = .63; 95% CI = .45–.86), having religious beliefs (OR = .59; 95% CI = .41–.85), and being a nursing home physician (OR = .34; 95% CI = .19–.60) were negatively associated with conceivability of performing euthanasia (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics Associated with the Physician's Conceivability of Performing Euthanasia in Case of Dementia (n = 1,052) a

| Absolute numbers | Euthanasia and assisted suicide conceivable N = 217 | Univariable | Multivariable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 494 | 25.3 | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 551 | 16.7 | .59 (.44–.80) | .63 (.45–.86) |

| Age, y | ||||

| <40 | 271 | 19.6 | .99 (.65–1.52) | |

| 40–54 | 522 | 21.6 | 1.13 (.78–1.63) | |

| ≥55 | 259 | 19.7 | Reference | — |

| Religious beliefs | ||||

| No | 697 | 24.0 | Reference | Reference |

| Yes | 342 | 13.5 | .49 (.35–.70) | .59 (.41–.85) |

| Specialty | ||||

| General practitioner | 540 | 23.7 | Reference | Reference |

| Nursing home physician | 195 | 7.7 | .27 (.15–.47) | .34 (.19–.60) |

| Clinical specialist | 317 | 23.3 | .98 (.71–1.36) | 1.27 (.83–1.94) |

| Experience, y | ||||

| <10 | 221 | 20.8 | Reference | — |

| ≥10 | 831 | 20.6 | .99 (.68–1.42) | |

| Completed palliative care training | ||||

| No | 558 | 22.9 | Reference | — |

| Yes | 485 | 18.1 | .75 (.55–1.01) | |

| SCEN physician b | ||||

| No | 1,012 | 20.3 | Reference | — |

| Yes | 33 | 33.3 | 1.97 (.94–4.13) | |

| Consultant palliative care/Member palliative care team | ||||

| No | 997 | 20.9 | Reference | — |

| Yes | 48 | 16.7 | .76 (.35–1.65) | |

| Ever received an explicit euthanasia request | ||||

| No | 270 | 17.0 | Reference | Reference |

| Yes but never performed euthanasia | 218 | 11.5 | .63 (.37–1.07) | .79 (.45–1.39) |

| Yes and ever performed euthanasia | 563 | 25.8 | 1.68 (1.17–2.44) | 1.94 (1.21–3.12) |

| Received a euthanasia request from a patient with dementia in the past year | ||||

| No | 1,005 | 20.6 | Reference | — |

| Yes | 27 | 29.6 | 1.62 (.70–3.76) | |

Note: Long dash indicates the item was entered in the regression but was eliminated in the stepwise procedure because P > .10. Statistically significant effects are in boldface type.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

The number of missing varied between 0 and 20 (1.9%).

Independent advisor for the euthanasia procedure.

DISCUSSION

Public Acceptance of Euthanasia in Patients with Advanced Dementia

Our study shows that 60% of the general public agreed that people with advanced dementia should be eligible for euthanasia. Studies from Finland (2002) and the United Kingdom (2007) examining public attitudes toward euthanasia in advanced dementia found that about 50% of the public agreed that euthanasia was acceptable in patients with severe dementia. 18 , 19 A more recent study from Finland found that 64% of the general public approved of euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia. 20 In Canada, Bravo et al. investigated the attitude of older adults and informal caregivers: 75% found it somewhat or totally acceptable to extend medical aid in dying to incompetent patients with advanced dementia based on a written request. 21 Other studies conducted in the Netherlands also found high levels of support for euthanasia in patients with severe dementia based on an advance directive, up to 77% in a study by Kouwenhoven et al. 22 , 23 An important notice is that support for the practice of performing euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia may depend on the wording and specific content of the question. When respondents were presented the vignette about a patient with advanced dementia with an advance directive for euthanasia and the physician performs euthanasia, 83% of the respondents agreed with the physician's act to perform euthanasia.

The finding from another study 24 that people holding religious views reported a lower acceptance of assisted dying in dementia was confirmed by our study. We found that being female, being Dutch, age between 40 and 69, and higher educational level were associated with a positive attitude toward euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia.

From other literature it is known that euthanasia in general is more broadly accepted by people with a higher educational level. 25 Younger, more educated, and Dutch respondents are more likely to be in favor of performing euthanasia. Younger people might attach more importance to autonomy and are probably less religious, which may explain the positive attitude toward euthanasia. Cohen (2014) noted that acceptance of euthanasia is strongly related to an attitude of tolerance toward freedom of personal choice, with those countries with a positive attitude toward freedom of choice usually also accepting euthanasia as an option for incurably ill people. 26 A possible explanation for the lower acceptance of euthanasia among the less educated is that education increases the value felt for personal autonomy and individualism. 27 It is unclear why women would find euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia more acceptable than men. In general, other studies show no relation between sex and acceptance of euthanasia. 28 Maybe the fact that women are more likely to develop dementia as compared with men, due to their longer life expectancy, plays a role. 29

Physicians' Acceptance of Euthanasia in Patients with Advanced Dementia

Less than one‐quarter of general practitioners and clinical specialists considered performing euthanasia conceivable in patients with advanced dementia with no severe comorbidities on the basis of a written advance directive. In nursing home physicians, only 8% considered performing euthanasia conceivable in these patients. Studies that have explored physician attitudes indicate that most physicians are opposed to euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia. 24 , 30 , 31 An older study by Rietjens et al. in 2005 among 391 physicians showed that 6% accepted euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia based on a living will. 23 A study by Bolt et al. performed in 2012 compared physicians with different specialties and showed that in case of advanced dementia on the basis of a written advance directive in the absence of severe comorbidities, 34% of general practitioners, 29% of clinical specialists, and 14% of nursing home physicians found it conceivable to perform euthanasia. 32 These percentages are somewhat higher than the percentage we found in our study. The increasing number of patients with dementia who request euthanasia may have made physicians more aware of the difficulties regarding the performance of euthanasia in this population. It is also possible that the legal prosecution of the physician who had performed euthanasia in a 74‐year‐old demented and incapacitated woman has made physicians more reluctant to consider euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia.

An online survey among 17 Belgian physicians specialized in dementia showed that although most participants (n = 13) approved the law on euthanasia, a majority (11) were against an extension of the law to allow euthanasia based on advance directives for patients with dementia. 33 In Canada, the level of support for extending medical aid in dying to incompetent patients with dementia among physicians caring for patients with dementia was 45%. This percentage was 71% when it concerned patients in the terminal stage of dementia, provided patients had made a written request before losing capacity. 34 This percentage of 71%, however, is not completely comparable with the percentage found in our study because in the vignette in the Canadian study, more information regarding the patient's suffering and life expectancy was provided. Nevertheless, the level of support for extending medical aid in dying to incompetent patients with dementia among physicians caring for patients with dementia was 45% in the Canadian study, much higher than the level of support among Dutch nursing home physicians. Dutch physicians might have more extensive experience with patients with dementia who request euthanasia. This may have resulted in a greater awareness of the difficulties of determining whether a patient meets the legal requirements in the Dutch situation. 34 Another possible explanation might be related to the low response rate (21%) in the Canadian study that may reflect a response bias.

Our study showed that being female and being religious were associated with lower conceivability of performing euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia. Being female and being religious were also associated with lower conceivability of performing euthanasia in patients with psychiatric disorders. 28

There is a large and significant difference in acceptance between physicians with different specialties. Conceivability of euthanasia was lowest among nursing home physicians, the physicians who are most often involved in the care for these patients. This reluctance could be due to nursing home physicians' experiences with and knowledge about the complexity of performing euthanasia in this specific group of patients 32 or to their knowledge about other options to alleviate suffering. 23

Training in palliative care was not associated with conceivability of euthanasia in patients with dementia. This might be because in the Netherlands palliative care and euthanasia are not seen as incompatible. Some argue that in certain circumstances, granting a patient's request for euthanasia itself must be seen as a means of providing appropriate care.

Discrepancy between Public and Physicians' Acceptance of Euthanasia in Patients with Advanced Dementia

This study shows a substantial difference in acceptance of euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia between the general public and physicians. Physicians are responsible for making decisions about euthanasia and performing it. 23 Performing euthanasia has an emotional impact on physicians that may be even bigger when the person receiving euthanasia is not capable of explicitly confirming their wish anymore. 22 In a qualitative study by Kouwenhoven et al., physicians emphasized the need for direct communication with the patient when making decisions about euthanasia. Physicians find adequate verbal communication with the patient important because they wish to verify the voluntariness of the patient's request and the unbearableness of suffering. Therefore, the extent to which physicians are willing to comply with advance euthanasia directives in patients with advanced dementia seems limited.35 Patients and relatives, however, often have high expectations of the feasibility of the advance directives for euthanasia. 36 This discrepancy may cause disagreement and tensions as physicians may feel pressured to perform euthanasia, and patients and families may feel that their expectations are not being met. A recent study by Evenblij et al. reported that pressure to grant a euthanasia request was mostly experienced by physicians who refused a request, especially if the patient was older than 80 years, had a life expectancy of more than 6 months, and did not have cancer. 37

In the Netherlands, as in some other Western European countries, an increase in public support for euthanasia was reported. 38 As society is aging, the number of people with dementia will increase. 39 Although the number of patients with advanced dementia who receive euthanasia is low (the review committee reported three patients with advanced dementia who received euthanasia in 2017 40 and two in 2018 6 ), it is not unlikely that the number of euthanasia requests from patients with advanced dementia will increase. This may motivate patients, families, and physicians to discuss mutual expectations in these complex situations in a comprehensive and timely manner.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study are the nationwide samples and the high response rates of the general public and the physicians. Selection bias may have played some role because CentERpanel participants were slightly older and more highly educated than the average Dutch population, and those with a non‐Dutch background were underrepresented. Selection bias also may have played a role because physicians who had experiences with requests or the performance of euthanasia in patients with dementia may have been more inclined to respond to the survey. Another limitation of this study is that the wording of the statements for the general public and physicians was slightly different.

Furthermore, in case of clinical specialists, it is possible that they do not consider it conceivable to perform euthanasia in patients with dementia because they are rarely involved in end‐of‐life care of these patients, not because they are opposed as a matter of principle. This probably holds to a lesser extent for general practitioners and nursing home physicians.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, there is a significant difference in support for euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia between the general public and physicians. Most of the Dutch general public (60%) is of the opinion that euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia is acceptable, whereas among physicians, especially nursing home physicians, the conceivability of performing euthanasia in patients with advanced dementia is low. This discrepancy may cause tensions because physicians may feel pressure to perform euthanasia, and patients' and families' expectations may not be met. It encourages patients, families, and physicians to discuss mutual expectations in a comprehensive and timely manner.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to all study participants for their contributions and to Inssaf El Hammoud for collecting the data.

Financial Disclosure

This study received funding from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; Project No. 3400.8002).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest for this article.

Author Contributions

All authors had full access to all the data (including statistical reports and tables) and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis. Designed the study: Onwuteaka‐Philipsen and van der Heide. Drafted the article: Brinkman‐Stoppelenburg. Checked the statistical analysis: Evenblij. All the authors interpreted the data and revised the article for important intellectual content.

Sponsor's Role

The sponsor had no role in the design, methods, subject, recruitment, datacollections, analysis and preparation of the article.

References

- 1. Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations . Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding [Act on termination of life on request and assisted suicide]. 2001. http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0012410/2014-02-15. Accessed July 16, 2019.

- 2. Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD, Brinkman‐Stoppelenburg A, Penning C, de Jong‐Krul GJ, van Delden JJ, van der Heide A. Trends in end‐of‐life practices before and after the enactment of the euthanasia law in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2010: a repeated cross‐sectional survey. Lancet. 2012;380(9845):908‐915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Onwuteaka‐Philipsen B, Legemaate J, van der Heide A, et al. Derde evaluatie Wet toetsing levensbeëindiging op verzoek en hulp bij zelfdoding [Third Evaluation of the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Act]. Den Haag, Netherlands: ZonMw; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Evenblij K, Pasman HRW, van der Heide A, Hoekstra T, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD. Factors associated with requesting and receiving euthanasia: a nationwide mortality follow‐back study with a focus on patients with psychiatric disorders, dementia, or an accumulation of health problems related to old age. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Regionale Toetsingscommissie Euthanasie [Regional Euthanasia Review Committees] . Jaarverslag 2009 [Annual report 2009]. https://www.euthanasiecommissie.nl/de-toetsingscommissies/uitspraken/jaarverslagen/2009/nl-en-du-fr/nl-en-du-fr/jaarverslag-2009. Accessed July 16, 2019.

- 6. Regionale Toetsingscommissie Euthanasie (Regional Euthanasia Review Committees) . Jaarverslag 2018 [Annual report 2018] https://www.euthanasiecommissie.nl/de-toetsingscommissies/uitspraken/jaarverslagen/2018/april/11/jaarverslag-2018. Accessed July 16, 2019.

- 7. de Beaufort ID, van de Vathorst S. Dementia and assisted suicide and euthanasia. J Neurol. 2016;263(7):1463‐1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Boer ME, Droes RM, Jonker C, Eefsting JA, Hertogh CM. The lived‐experiences of early‐stage dementia and the feared suffering: an explorative survey [in Dutch]. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;41(5):194‐203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rietjens JA, van Tol DG, Schermer M, van der Heide A. Judgement of suffering in the case of a euthanasia request in The Netherlands. J Med Ethics. 2009;35(8):502‐507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rurup ML, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD, van der Heide A, van der Wal G, van der Maas PJ. Physicians' experiences with demented patients with advance euthanasia directives in The Netherlands. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(7):1138‐1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Boer ME, Hertogh CM, Droes RM, Jonker C, Eefsting JA. Advance directives in dementia: issues of validity and effectiveness. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(2):201‐208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller DG, Dresser R, Kim SYH. Advance euthanasia directives: a controversial case and its ethical implications. J Med Ethics. 2019;45(2):84‐89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jongsma KR, Kars MC, van Delden JJM. Dementia and advance directives: some empirical and normative concerns. J Med Ethics. 2019;45(2):92‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bolt EE, Pasman HR, Deeg DJ, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD. From advance euthanasia directive to euthanasia: stable preference in older people? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(8):1628‐1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Nooijer K, van de Wetering VE, Geijteman EC, Postma L, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. Written advance euthanasia directives in mentally incompetent patients with dementia: a systematic review of the literature. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2017;161:D988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Central Committee on Reseach Involving Human Subjects C . Your research: Is it subject to the WMO or not? 2019. https://english.ccmo.nl/investigators/legal-framework-for-medical-scientific-research/your-research-is-it-subject-to-the-wmo-or-not. Accessed August 29, 2019.

- 17. CentERdata Institute for data collection and research . CentERdata. https://www.centerdata.nl/en/projects-by-centerdata/the-center-panel. Accessed July 16, 2019.

- 18. Ryynanen OP, Myllykangas M, Viren M, Heino H. Attitudes towards euthanasia among physicians, nurses and the general public in Finland. Public Health. 2002;116(6):322‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams N, Dunford C, Knowles A, Warner J. Public attitudes to life‐sustaining treatments and euthanasia in dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(12):1229‐1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Terkamo‐Moisio A, Pietila AM, Lehto JT, Ryynanen OP. Attitudes of nurses and the general public towards euthanasia on individuals with dementia and cognitive impairment. Dementia (London). 2019;18(4):1466‐1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bravo G, Trottier L, Rodrigue C, et al. Comparing the attitudes of four groups of stakeholders from Quebec, Canada, toward extending medical aid in dying to incompetent patients with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(7):1078‐1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kouwenhoven PS, Raijmakers NJ, van Delden JJ, et al. Opinions of health care professionals and the public after eight years of euthanasia legislation in the Netherlands: a mixed methods approach. Palliat Med. 2013;27(3):273‐280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rietjens JA, van der Heide A, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G. A comparison of attitudes towards end‐of‐life decisions: survey among the Dutch general public and physicians. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(8):1723‐1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tomlinson E, Stott J. Assisted dying in dementia: a systematic review of the international literature on the attitudes of health professionals, patients, carers and the public, and the factors associated with these. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(1):10‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cohen J, Marcoux I, Bilsen J, Deboosere P, van der Wal G, Deliens L. European public acceptance of euthanasia: socio‐demographic and cultural factors associated with the acceptance of euthanasia in 33 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(3):743‐756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cohen J, Van Landeghem P, Carpentier N, Deliens L. Public acceptance of euthanasia in Europe: a survey study in 47 countries. Int J Public Health. 2014;59(1):143‐156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Caddell DP, Newton RR. Euthanasia: American attitudes toward the physician's role. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(12):1671‐1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Evenblij K, Pasman HRW, van der Heide A, van Delden JJM, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD. Public and physicians' support for euthanasia in people suffering from psychiatric disorders: a cross‐sectional survey study. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Niu H, Alvarez‐Alvarez I, Guillen‐Grima F, Aguinaga‐Ontoso I. Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer's disease in Europe: a meta‐analysis. Neurologia. 2017;32(8):523‐532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rurup ML, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD, van der Heide A, van der Wal G, Deeg DJ. Frequency and determinants of advance directives concerning end‐of‐life care in The Netherlands. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(6):1552‐1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Tol D, Rietjens J, van der Heide A. Judgment of unbearable suffering and willingness to grant a euthanasia request by Dutch general practitioners. Health Policy. 2010;97(2–3):166‐172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bolt EE, Snijdewind MC, Willems DL, van der Heide A, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD. Can physicians conceive of performing euthanasia in case of psychiatric disease, dementia or being tired of living? J Med Ethics. 2015;41(8):592‐598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Picard G, Bier JC, Capron I, et al. Dementia, end of life, and euthanasia: a survey among dementia specialists organized by the Belgian Dementia Council. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;69(4):989‐1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bravo G, Rodrigue C, Arcand M, et al. Quebec physicians' perspectives on medical aid in dying for incompetent patients with dementia. Can J Public Health. 2018;109(5–6):729‐739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kouwenhoven PS, Raijmakers NJ, van Delden JJ, et al. Opinions about euthanasia and advanced dementia: a qualitative study among Dutch physicians and members of the general public. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rurup ML, Pasman HR, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD. Advance euthanasia directives in dementia rarely carried out. Qualitative study in physicians and patients [in Dutch]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154:A1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Evenblij K, Pasman HRW, van Delden JJM, et al. Physicians' experiences with euthanasia: a cross‐sectional survey amongst a random sample of Dutch physicians to explore their concerns, feelings and pressure. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka‐Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician‐assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316(1):79‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63‐75.e62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Regionale Toetsingscommissie Euthanasie [Regional Euthanasia Review Committees] . Jaarverslag 2017 [Annual report 2017]. https://www.euthanasiecommissie.nl/de-toetsingscommissies/uitspraken/jaarverslagen/2017/mei/17/jaarverslag-2017. Accessed July 16, 2019.