Abstract

Perfectionism can result in negative consequences for those who set unattainable goals and repeatedly strive to achieve high standards. Relying on inflexible behaviors and building one's self‐worth around success can become problematic and affect performance, interpersonal relationships, and cause mental distress. In the current case illustration, perfectionism's negative implications are depicted through a client named Sara, a stressed‐out junior physician who just graduated from medical school. Struggling with issues related to self‐worth, depression, worry, independence, and interpersonal difficulties, Sara underwent cognitive behavior therapy during 15 sessions. The case illustration shows how an individualized conceptualization of perfectionism can be made and what is important to target in treatment, such as preventing the need for repeated checking, conducting surveys to refute dysfunctional beliefs, and introducing activities that are unrelated to accomplishments. Current research on the efficacy of treating perfectionism is also summarized and interventions particularly relevant for clinical practice are presented.

Keywords: case illustration, clinical practice, cognitive behavior therapy, individualized conceptualization, perfectionism

1. INTRODUCTION

Perfectionism is sometimes conceived as a desirable trait that involves such features as setting high standards, striving for achievement, and being conscientious. Society at large also tends to take notice and reward many aspects common in perfectionism, in particular the ability to be organized and highly attentive to details (Stoeber, 2017). Meanwhile, dictionaries typically define it as the refusal to accept what falls short of perfection, thus focusing on the quality of one's actions (Egan, Wade, Shafran, & Antony, 2016). However, despite sometimes being perceived as helpful, perfectionism can occasionally lead to negative consequences for some. Regardless of definition, this is generally characterized by rigidity, lack of compromise, and setting unrealistic goals, which in turn might affect one's performance and mental and physical health (Egan, Wade, & Shafran, 2011). Likewise, perfectionism has strong interpersonal implications, affecting how a person wants to appear in the eyes of others and manifested through difficulties maintaining close relationships. Hewitt and Flett (1991) were early to discuss perfectionism from a relational perspective, delineating a tripartite component involving self‐oriented perfectionism, that is, setting high standards for oneself, other‐oriented perfectionism, that is, expectations and beliefs regarding the capacities of others, and socially prescribed perfectionism, that is, the perception that others have high expectations of oneself and to be critically appraised. Together with the fact that perfectionism also has a clear dispositional aspect to it, these components constitute a clinical model referred to as the Comprehensive Model of Perfectionistic Behavior (Hewitt, 2020). More specifically, this can be portrayed as being demanding of oneself and others, and to compulsively and unremittingly strive toward outcomes that are unreasonable to attain (Egan et al., 2016). According to Shafran, Cooper, and Fairburn (2002), perfectionism can be defined as “the overdependence of self‐evaluation on the determined pursuit of personally demanding, self‐imposed standards in at least one highly salient domain, despite adverse consequences” (p. 778). Their description suggests that many perfectionists have a way of perceiving themselves, others, and the world that is highly dependent on achievement and reaching certain standards. Their sense of self‐worth is thereby extremely fragile as failure to realize these standards easily results in self‐criticism and negative self‐evaluation. Furthermore, given that many perfectionists rely on just one or a few life domains, their sense of self‐worth is also tied to attainment in these areas, for example, succeeding at work, leaving them vulnerable to disappointment and distress. As the person continuously strives to achieve her goals, the consequences can be dire, resulting in a constant fear of failure and negative response from others, inflexibility, and a number of emotional, social, physical, cognitive, and behavioral outcomes, such as depression, relationship issues, stress and insomnia, difficulties concentrating, and procrastination (Shafran et al., 2002).

The idea that perfectionism can lead to adversities has been discussed extensively in the literature and is established in several empirical studies. More recently, Limburg, Watson, Hagger, and Egan (2017) provided an overview of the research by conducting a systematic review and meta‐analysis. As perfectionism is considered to be a multidimensional construct, consisting of two higher‐order dimensions, their findings separate the two and their respective relationship with psychopathology. Perfectionistic concerns, that is, the tendency to critically appraise one's own behavior, be preoccupied with others' perception of oneself, and the difficulty to feel satisfied by one's performance, is primarily associated with depression and anxiety disorders. Meanwhile, perfectionistic strivings, that is, the tendency to set high standards and being demanding of oneself, is more related to eating disorders. Hence, both dimensions are linked to psychopathology, but perhaps demonstrating slightly different clinical profiles. Based on the current evidence, Egan et al. (2016) also suggest that perfectionism is a transdiagnostic process. In other words, a factor involved in the etiology and maintenance of a large number of psychiatric disorders, as well as a factor that interferes or affects the initiation or execution of treatment, for example, less engagement in exposure and response prevention in obsessive‐compulsive disorder, increased risk of dropout among patients with anorexia nervosa, and poorer therapeutic alliance. In addition, Stoeber (2017) lists some of the other implications that sometimes accompany perfectionism, for example, problems maintaining significant relationships with others, maladaptive coping strategies in relation to chronic conditions such as tinnitus, physical health issues following increased stress levels, and difficulties managing school, work, and athletic activities.

2. A COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL CONCEPTUALIZATION OF PERFECTIONISM

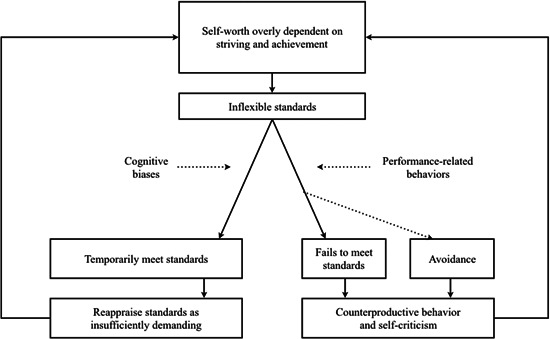

Following a review of the literature, Shafran et al. (2002) developed and proposed a cognitive‐behavioral conceptualization intended to guide the assessment and treatment of perfectionism (see Figure 1). At its core lies a fear of failure and relentless pursuit of success that result in a person's sense of self‐worth being intricately linked to achievement. This will, in turn, create a set of inflexible standards (i.e., intermediate beliefs according to a cognitive model, comparable to a set of rigid attitudes and assumptions), leading to rule‐governed behaviors, for example, “I must always make sure there are not errors in my text.” Hence, if a person believes she is only good enough when she succeeds at fulfilling her goals, she will eventually develop very strict rules about how to behave in various settings.

Figure 1.

The cognitive‐behavioral conceptualization of perfectionism by Shafran et al. (2002)

Stemming from these tightly held inflexible standards, different forms of cognitive biases are derived. This can consist of dichotomous thinking (i.e., seeing one's performance in black or white), overgeneralization (e.g., “Because I made a mistake, I am utterly useless”), and selective attention (e.g., disregarding the positive). In addition, performance‐related behaviors intended to uphold one's standards are common, for example repeated checking, seeking reassurance from others (e.g., “Was I good enough?”), and to compare oneself to others. According to a cognitive model, these processes are then responsible for maintaining the ongoing problem, and in relation to perfectionism, the key to understand what keeps the person being fearful of failure and striving for success.

Fundamental to the conceptualization by Shafran et al. (2002) is that the end result of one's performance puts the person in a catch 22‐like situation, that is, a paradox. Should she meet her standards, the success if often temporary, leading to a short‐term improvement in self‐evaluation, which reinforces the need to pursue these standards again (i.e., intermittent reinforcer according to a behavioral model, similar to a slot machine that rewards a behavior on an irregular basis). However, Shafran et al. (2002) argue that this is likely to be reappraised as insufficiently demanding, which means that the person will raise the bar in the future (e.g., “I only succeeded because my teacher was being nice to me, I have to do better the next time around”). In the alternative scenario, the person instead fails to meet her standards, either because they were impossible to attain to begin with, or because she determines success in an all‐or‐nothing fashion (i.e., missing the fact that the goal was achieved from a more objective point of view). Sometimes, the idea of not being able to live up to one's standards can also result in avoidance of a task altogether. Either way, the direct implications are often self‐criticism and engagement in different counterproductive behaviors, such as procrastination, which can be perceived as coping strategies for managing emotional discomfort and to protect one's ego (e.g., “Had I only started working on time I would have been able to perform much better”). In the end, regardless of performance and ability to fulfill one's standards, the outcome acts as a feedback loop that keeps fueling the idea that one's self‐worth is derived from achievement, thus creating a vicious spiral.

The conceptualization is, however, not only a theoretical model, but has received some support from empirical studies. Shafran, Coughtrey, and Kothari (2016) provide an overview of the research, demonstrating that experimental investigations have confirmed biased interpretations of perfection‐relevant material among those who have higher scores on self‐report measures of perfectionism. Likewise, different performance‐related behaviors, defined as the duration, frequency, or time spent to complete certain tasks, have also been found to be elevated among perfectionists, e.g., repeated checking. Furthermore, perfectionism is related to feelings of shame and guilt after failing a task, as well as increased levels of distress and dysfunctional thinking and decreased levels of persistence when trying to complete activities under evaluative threat, reflecting some of the self‐critical thoughts and counterproductive behaviors that arise during their performance. Similarly, studies show that perfectionists tend to strive toward more difficult goals after achieving their standards. Hence, there is preliminary evidence suggesting that several aspects of the conceptualization might be correct, illustrating important mechanisms that need to be targeted in treatment to break a pattern that has become maladaptive.

3. COGNITIVE BEHAVIOR THERAPY (CBT) FOR PERFECTIONISM

A number of treatments for perfectionism have been put forward during the last decades, some having its foundation in CBT (Antony & Swinson, 1998). Shafran et al. (2002) described how some of these cognitive and behavioral interventions fit with their conceptualization of maintaining processes and proposed a general framework of working with perfectionism in treatment. Four components were outlined as essential: (1) providing psychoeducation and mapping out an individualized conceptualization, (2) broadening the areas for self‐evaluation, (3) conducting behavioral experiments to test out beliefs and predictions, and (4) address personal standards and self‐criticism. The content has been developed further since, and is available as both a therapist manual (Egan et al., 2016) and a self‐help book (Shafran, Egan, & Wade, 2018). The treatment can then be administered “as a stand‐alone intervention or as an adjunct to evidence‐based treatments for other forms of psychopathology if clinical perfectionism is seen as a barrier to change” (Shafran et al., 2016; p. 163). Delivered specifically for perfectionism usually involves 10 individual face‐to‐face sessions over 8 weeks (50‐min sessions), including biweekly sessions during the first 2 weeks. Depending on the individualized conceptualization, type of format (e.g., group), focus (e.g., add‐on to a treatment of a psychiatric disorder), length and delivery might, however, warrant some adaptation (Egan et al., 2016).

With regard to its content (see Table 1), the emphasis is primarily on processes maintaining perfectionism and not its origin, that is unless hypotheses regarding its etiology is important for treatment or essential for developing rapport. At first, the person explores the pros and cons of her perfectionism to realize that it is associated with both advantages and disadvantages. This can increase motivation to change and avoid a discussion about the need to lower standards or not. This is followed by an introduction to the conceptualization of perfectionism, psychoeducation on the relationship between perfectionism and performance, and the use of self‐monitoring. Investigating the thoughts, emotions, and behaviors associated with perfectionism can help the person understand maintaining processes, which sets the occasion for such interventions as behavioral experiments (e.g., gathering information and testing alternative hypotheses), cognitive restructuring (e.g., pie charts and challenging thinking errors), activity scheduling of pleasurable events, and strategies for problem‐solving. Moreover, the treatment also features various interventions for relaxation, time‐management, dealing with procrastination, responding to self‐criticism through practicing self‐compassion (e.g., dealing with self‐critical thoughts through self‐kindness), and lastly relapse prevention.

Table 1.

Treatment content of cognitive behavior therapy for perfectionism (Egan et al., 2016)

| Session number and key ingredient | Examples of between‐session assignments | Current case illustration and remarks |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Assessment and investigating the motivation change, for example, understanding the pros and cons of perfectionism | Explore and complete worksheet on motivation to change | Sessions 1 and 2 |

| Motivation to change was not explicitly addressed as motivation was considered high | ||

| 2. A cognitive behavioral conceptualization of perfectionism | Review the individualized conceptualization and add any additional information | Sessions 2 and 3 |

| 3. Psychoeducation and self‐monitoring | Complete worksheet on self‐monitoring of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors related to perfectionism in different situations | Sessions 1–4 |

| 4. Performance‐related behaviors, behavioral experiments, and surveys | Based on the previous assignment, complete behavioral experiments and/or surveys concerning performance‐related behaviors | Sessions 4–12 |

| Behavioral experiments constituted a cornerstone of treatment | ||

| 5. Self‐evaluation and life domains | Based on the pie chart from the session, complete behavioral experiments related to expanding the life domains connected to self‐evaluation | Sessions 6–12 |

| Expanding the life domains was made continuously throughout treatment | ||

| 6. Rigidity, rules, and standards | Complete behavioral experiments targeting rigid rules and dichotomous thinking, performing activities that are believed to be “substandard,” and spend less time on tasks | Sessions 4–12 |

| Explored and addressed using behavioral experiments, pie charts, and cognitive restructuring | ||

| 7. Cognitive biases, pleasurable activities, refocusing attention, cognitive restructuring, and thinking errors | Engage in pleasurable activities and complete thought diaries | Sessions 6–12 |

| 8. Problem‐solving and deriving strategies, for example, relaxation, time‐management, and managing procrastination | Complete behavioral experiments that increase the amount of time spent on relaxation, rest, and different “unproductive” activities, engage in strategies identified as most suitable for managing procrastination | Sessions 10–15 |

| Primarily related to applied relaxation | ||

| 9. Self‐criticism and self‐compassion | Complete thought diaries intended to increase self‐compassionate thinking | Not administered as self‐criticism and self‐compassion was found less relevant by the client |

| 10. Relapse prevention | Continued use of behavioral experiments and planning ahead to prevent relapse | Sessions 13–15 |

| Regularly discussed and reviewed throughout the last sessions |

Two systematic reviews and meta‐analyses have summarized the efficacy of CBT for perfectionism (Lloyd, Schmidt, Khondoker, & Tchanturia, 2015; Suh, Sohn, Kim, & Lee, 2019), demonstrating large effects on self‐report measures. In terms of the impact on psychiatric disorders, the outcomes are also encouraging, but with somewhat smaller effects. Lastly, it should also be noted that different formats yielded comparable outcomes (Suh et al., 2019), such as Internet‐based CBT (Rozental et al., 2017; Zetterberg et al., 2019), which may improve dissemination.

4. CASE ILLUSTRATION

4.1. Presenting problem and client description

The author of the current case illustration works part‐time in a private practice. All of his clients are self‐referred, seeking treatment primarily for perfectionism, procrastination, depression, anxiety disorders, and work‐related stress. The clients can cover their treatment via private insurance or pay for the service themselves, which means that the they are usually more motivated and have a higher socioeconomic status than most clients in routine care settings in Sweden, which offers its citizens healthcare for free. With this context in mind, Sara reached out to the author after hearing him discuss perfectionism on a radio show on mental health on Radio Sweden. A first appointment was scheduled the next week during which an initial assessment was made.

Sara was a 25‐year‐old female of Swedish descent who just graduated from medical school and was on her way to start her internship in a remote rural town. She came from a stable background with two caring parents and two siblings, all of whom were academically and professionally accomplished. Sara described her childhood in generally positive terms, but that there was an underlying expectation to always strive for achievement. “It's not that my parents were harsh if I didn't succeed or anything, but there was this sense of letting them down if you didn't perform your best.” Sara went on to receive outstanding grades in school and was very athletic in her teens, practicing both soccer and basketball several days a week. Throughout this period Sara had bouts of disordered eating and issues related to body‐image, but nothing she believed warranted treatment or ever came to the attention of her parents. Shortly after graduation, Sara was admitted to medical school and moved to a bigger city. During this time, she thrived intellectually and became active in extracurricular activities, such as helping out organizing faculty events, engaging in committee work, and putting in hours as a research assistant. Her schedule however quickly became overwhelming, creating problems with her sleep and making her increasingly restless. Sara eventually experienced a panic attack, “which I of course didn't realize at the time, thinking it had to do with my physical health, being a medical student and all, but I finally understood that something wasn't quite right.” Sara turned to a counselor at the university for some help, but ended treatment prematurely. “It was all about lowering my standards, which just made me mad.” Ultimately, she learned how to cope with her symptoms herself, although the feeling of being stressed out never completely disappeared. According to her, being busy had become a part of life, with a haunting sense of not being good enough fueling her need to perform. Apart from her studies, Sara recounts having few interests or hobbies except for running, which she monitored closely via her smartphone to keep track of her time.

During the session, Sara appeared depressed and nervous. Her mood was low and she occasionally cried while reviewing her situation. She also came across as tense, repeatedly checking her watch and having a hard time sitting still. As for the reason making the appointment, Sara described feeling more and more worried about her future internship, especially that she might not live up the same standards as her colleagues. Her behavior had also recently started to affect her relationships with others, with both her friends and partner becoming increasingly frustrated with her constant reassurance seeking and tendency to overdo tasks and assignments. Furthermore, Sara explained that she also had a hard time letting go of things, making her dwell on recent and upcoming decisions. This created a lot of stress and anxiety, which she tried to cope with by talking them over with her partner, engaging in repeated checking, or staying up late ruminating. In one such scenario, she was unable to book tickets and hotel for a trip with her sister, ending up searching different options for hours without being able to make up her mind. “I wanted it to be a nice vacation, but I just couldn't decide fearing I might make the wrong choices.” Similarly, handing in course work could take forever as she had to make sure that it was perfect. Sara explained that she had probably always been like this, but that the situation had escalated recently and started to take its toll on her well‐being. Furthermore, recent remarks from her partner has made her more aware of her problems and that it was affecting their relationship negatively, which motivated her to finally seek treatment. Just before ending the session, she pointed out that she worried her perfectionism might affect treatment, at the same time downplaying her problems as less severe. “You probably have other cases that need treatment more than I do.”

4.2. Case formulation

Between the first two sessions Sara completed a homework assignment and a few self‐report measures intended to inform the case formulation and provide an idea of her symptom levels. First, she listed behavioral excesses and deficits using just a piece of paper with two columns: “things I do too much of” and “things I lack.” This type of overview gives some insights into the client's current coping strategies, activities, and skills. In terms of behavioral excesses, she wrote “rumination, worry, difficulties communicating, fear of missing out, inner stress, thinking that everything matters and that it has to be perfect,” while putting down “independence, making decisions by myself, mindfulness, carefree, take things more lightly” as behavioral deficits. Meanwhile, her self‐report measures demonstrated she had elevated symptoms of worry and anxiety (12 points, suggesting moderate severity according to the Generalized Anxiety Disorder; GAD‐7), depression (16 points, implying a need for further assessment of mood disorder on the Patient Health Questionnaire; PHQ‐9), and perfectionism (33 points on the Concern over Mistakes subscale and 28 points on the Personal Standards subscale from the Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Questionnaire; FMPS), but no sign of obsessive‐compulsive disorder on the Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (OCI‐R; 6 points).

During the second session, a joint understanding of the processes maintaining her problems was also made using functional analyses, delineating antecedents (i.e., triggers), actions (i.e., cognitions and observable behaviors), and consequences (e.g., advantages and disadvantages of acting a certain way) in everyday situations. In one such case, Sara described performing a task in her work as a research assistant (see Table 2). It became clear she was fearful of making mistakes in front of her colleagues, thinking it would lead to their disapproval and criticism. As these predictions made her feel anxious, it seemed reasonable for her to cope with the situation by repeatedly checking if she actually got the numbers right. However, although providing some short‐term relief, her actions eventually made her feel bad, while still thinking about possible errors she might have missed. “That's pretty much it, regardless of what I'm doing I'm constantly fearing I'll mess things up and that others will think less of me.”

Table 2.

Functional analyses of problematic situations for the client

| Antecedent | Behavior | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Were to submit to our research group three tables of numbers that I was responsible for | Started thinking “what if there's an error somewhere,” checked the numbers with the output I had, started to get anxious and stressed out, imagined getting yelled at by my colleagues, repeated this procedure probably five times over the course of 2 h before sending it off | Felt more and more confident everything was alright each time I checked the numbers, calmer and less anxious |

| However, got home late from university, felt bad, still nervous about someone finding errors in the numbers I sent out | ||

| A close friend of mine asked me to come over to watch a game of soccer | Started thinking “I don't want to say yes to her, because I'd rather spend time with my partner tonight, but what if she gets mad at me?,” worried, believed she might get mad, ruminated, asked my partner what to say | Went through different scenarios in my head, which made me feel better at first. Talking to my partner also made me feel more secure |

| Felt bad about myself for not managing the situation on my own, noticed that my partner was a bit frustrated, wasted a lot of time ruminating all of this |

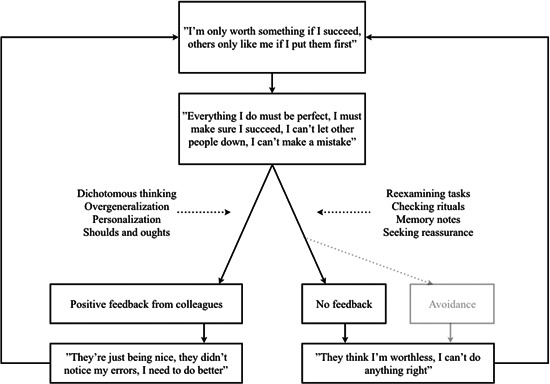

Going through an additional example together (see Table 2) suggested that Sara was highly conscious about how others perceived her and that she tried to avoid a situation where others would think less of her. It also confirmed some of the things she previously listed as behavioral excesses and deficits, such as her rumination. In line with the treatment outline, Sara completed further homework assignments monitoring thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that eventually demonstrated a core belief that her self‐worth was based on striving for success and achievement. In addition, there was also an idea of having to be liked by others, transpiring through her insecurities in interpersonal relationships. This had turned into a set of inflexible standards, which made her think she needed to do things perfectly and could not let people around her down. Exploring her actions and ways of perceiving various events also highlighted a number of cognitive biases, such as dichotomous thinking (“you either get it or you're just not smart enough”), overgeneralization (“since I made a mistake, I'm worthless”), personalization (“our flight got delayed by two hours, it was my fault”) and should and oughts (“if you really get it, you shouldn't have to try so hard”). Recurrent themes across all of these thinking errors were the lack of variation with regard to how Sara perceived herself and her own performance (e.g., good‐bad and always‐never). Meanwhile, she attributed success to something other than herself and seeing failure as her own making. Furthermore, several types of performance‐related behaviors became apparent, most notably re‐examining tasks to prevent making mistakes (e.g., rereading emails numerous times to check for spelling errors), different checking rituals to make sure things felt “just right” (e.g., reviewing patients' medical records from years back so as to not miss anything “vital”), relying on memory notes to prevent forgetting “essential” details (e.g., keeping a notebook with detailed information from meetings), and seeking reassurance from others when making decisions or determining if she did things the correct way (e.g., asking her partner on several occasions what dinner to have when eating out). In relation to her performance at work (see Figure 2), Sara ended up re‐evaluating her standards so that she would do better next time around, or, interpreted the comments she received (or lack thereof) as a sign of not being good enough. This was then fed back to her idea of only being worth something if she succeeded, continuing her strive toward achievement, with similar processes being responsible for also preserving her interpersonal difficulties.

Figure 2.

An individualized conceptualization of the client

4.3. Course of treatment

After reviewing the individualized conceptualization together, Sara confirmed the proposed maintaining processes. Her motivation to change was also explored briefly in session by discussing the advantages and disadvantages of perfectionism mainly from the perspective of her performance. This was done using a U‐shaped curve that is turned upside down, illustrating the idea of increasing levels of perfectionism having many benefits to start with, but becoming increasingly associated with less output. Having been very athletic growing up, Sara recognized this trend, using the metaphor of an athlete overtraining and injuring herself. A treatment rationale was then provided, adapted from the outline by Egan et al. (2016). In particular, the importance of targeting cognitive biases and performance‐related behaviors were discussed and agreed upon, such as through the use of behavioral experiments. In this case, using hypotheses and testing predictions fit well with her training as a medical doctor and work as a research assistant. Sessions were now provided once every other week to make enough room for homework assignments. Sara started out experimenting with her tendency to reexamine tasks to make sure she made no mistakes, that is, to explore what happens if she submitted tables and figures to her colleagues without repeatedly going through the numbers until it feels “just right.” One prediction was that her colleagues would point out all the errors she made and be disappointed with her (Hypothesis A). An alternative scenario would be that no one would take notice (Hypothesis B). After gathering the data she came back with the results to the next session.

(Therapist): So, one of your predictions was that, since you weren't triple‐checking all your numbers, that you'd make mistakes and that they'd be upset with you, right?

(Sara): Correct, and, you know, it's funny looking back, because of course, no one said a thing. And even though I did notice a small typo in one of the tables after sending it off, no one seemed to care.

(Therapist): That's interesting. So, given this little experiment of ours, what have you learned about similar situations like this one?

(Sara): Well, for one thing, you hardly get any feedback on tasks like this, but I also guess that my efforts in making sure everything was correct wasn't really necessary, you know. Nothing happened despite the fact I actually made a typo.

Behavioral experiments became a key component in treatment because of its usefulness in refuting maladaptive beliefs Sara made about her performance and the need to rely on certain types of behaviors. Hence, in a similar fashion, other checking rituals and the use of memory notes were targeted. Likewise, behavioral experiments intended to generate new hypotheses were also employed, such as when she did not have a clear picture of what standards to expect with regard to her performance. For example, Sara made short surveys among those she trusted concerning such issues as the number of hours they put into studying for an exam and whether or not they made any mistakes at work. This opened her eyes to the fact that her bar was sent much higher than most people and gave her a different perspective of what constitutes failure, particularly the notion that she could learn from them.

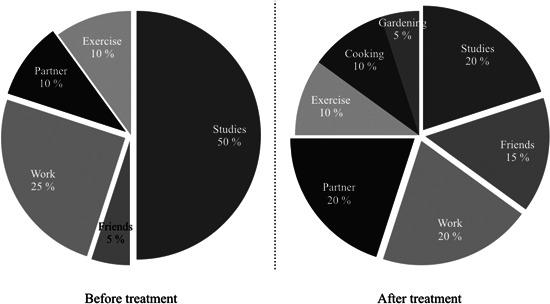

Meanwhile, one intervention in particular was used in parallel to Sara's behavioral experiments, aimed at changing the basis of her self‐evaluation. This consisted of completing a pie chart together in‐session of the domains on which she currently based her own sense of self‐worth (see Figure 3), which made it apparent that most of these areas were related to performance.

(Therapist): Do you notice anything in particular while seeing this in front of you?

(Sara): Yeah, studies and work make up 75%, so I guess there's not much left for anything else.

(Therapist): I can see that. And so, in relation to we've talked about before, in terms of self‐worth and everything, what do you make of this?

(Sara): That I only feel good about myself when I do well in my studies or at work?

(Therapist): Exactly. But could I also add something else? If you only derive your sense of self‐worth, of being good enough, from these two pieces, what do you think happens if you, say, struggle a bit with what you're doing in these areas?

(Sara): I see, yeah, you mean that if I don't succeed at, let's say my work, I feel bad about myself in general, and not just about things related to my work?

Figure 3.

A pie chart of the client's life domains during and after treatment

Using a pie chart fits well with the definition of perfectionism as the determined pursuit of “self‐imposed standards in at least one highly salient domain” (p. 778; Shafran et al., 2002), reflecting a central part of treatment: to broaden the domains Sara used for self‐evaluation. Furthermore, the pie chart illustrated a clear lack of relaxation and little room for leisure. Treatment therefore focused on expanding those areas that were seen as important to her but presently made up no more than 25% of her sense of self‐worth. Sara started making plans with her friends and partner, such as going out hiking in a nearby nature reserve. In addition, she also proposed taking up cooking, which she said she enjoyed but never believed she had any time for. As for her exercise routine, other measures were employed. Due to her previous history of disordered eating and issues related to body‐image, encouraging increased activity within this area could have had a negative impact. Consequently, Sara began running without monitoring her performance or listening to up‐tempo music, instead focusing on such aspects as what course to take and noticing her surroundings. Lastly, time to unwind each evening was created to reduce her stress levels and help her sleep better.

To further target Sara's cognitive biases and tightly held inflexible standards, various interventions aimed at promoting cognitive restructuring were also implemented. These ranged from taking the perspective of a friend (“You mentioned earlier that you'd feel like a complete failure if you'd make a mistake in class—what would you tell a friend saying something like this?”), exploring thinking errors like seeing things in black‐or‐white (“Coming back to what you just said, that you're either a success or a failure at what you do, what would you label that in relation to those thinking errors we've talked about before?”), and investigating one's performance using a continuum.

(Therapist): Let's say we could put down this idea of making an incision being either top‐notch or really really bad, and that we were to put these two extremes on the far ends of this line on the whiteboard here…who would you like to place on top?

(Sara): Ehm…I don't know, maybe John, he's extremely skilled, he's a natural talent.

(Therapist): Ok, so let's put John over here. And who would be at the bottom?

(Sara): I mean…no one's that bad! You wouldn't make it through medical school if you can't put the incision right. But I guess…Miriam?

(Therapist): So Miriam goes over here, not at the far end, but almost. And where would you like to put yourself?

(Sara): I knew you were going to ask me that…I see your point. Somewhere above the mean of this distribution [laughs].

Challenging thinking errors and adapting a more flexible way of evaluating one's performance eventually helped Sara manage her cognitive biases and rule‐governed behavior. These interventions were followed suit by additional behavioral experiments testing out new ways of responding in different situations, such as with regard to “unproductive” activities. For example, after one session, Sara explored what happened when she cut down the number of hours dedicated to her work and introducing regular coffee breaks. Another one was related to her difficulties making decisions on her own (e.g., picking one alternative and sticking to it, or, alternatively, to make up her mind without asking her partner for advice). The same approach was useful when Sara later started her internship, as this transition initially created a lot of worry and returned some of her performance‐related behaviors, e.g., spending too much time reading the nitty gritty details in patient records to prevent making mistakes. Here, Sara could make use of what she had learned by deriving new behavioral experiments to be tested in real‐life settings.

The move to a remote rural town eventually made the sessions less frequent. However, assessments and reviews were made possible via telephone and video conferencing. At this point in treatment, no further interventions were introduced, with the exception of applied relaxation (Öst, 1987). Despite having made significant changes to her schedule and introduced new activities in her life, she still experienced restlessness and bouts of anxiety, which was exacerbated by work‐related stress caused by her internship. Sara was therefore advised to use applied relaxation as a coping strategy, beginning with progressive relaxation two times a day (i.e., applying tension and release of muscle groups), followed by shorter and more applicable exercises intended to be used whenever she felt worried, anxious, or tense. Sara kept track of how relaxed she was before and after each time she used it. Despite some initial difficulties related to rumination or falling asleep while practicing, its continued use slowly had a positive effect on her stress level and ability to manage situations at work.

4.4. Outcome and prognosis

Treatment ended after 15 sessions, with the last sessions focusing on relapse prevention and maintaining what she had learned. As Sara had moved to a remote rural town, but still checked in with the author, she was able to become increasingly independent and was able to demonstrate on her own how to successfully manage a number of difficult situations that emerged during her internship. A follow‐up assessment was made during one of the last appointments to examine the benefits of treatment and any residual symptoms. An updated pie chart demonstrated a more balanced distribution of the domains from which she based her self‐evaluation, suggesting that she had broadened her activity repertoire and might be less vulnerable to self‐criticism if she does not succeed in her studies or at work (see Figure 3). She also confirmed that her relationships had gotten better as she stopped herself from seeking reassurance and became more independent in her decision‐making. With regard to worry and anxiety, she scored 2 points (GAD‐7), which is below the cut‐off of 5 points for mild problems. In terms of depression, Sara had 4 points (PHQ‐9), below the cut‐off of 5 points often used as a sign of further screening. As for perfectionism, she scored 15 points on the Concern over Mistakes subscale, but 25 points on the Personal Standards subscale (FMPS). Although no cut‐offs exist for this self‐report measure, clinical trials have often used 22 points as representing a functional population for the first subscale (Shafran et al., 2017), but no such rule‐of‐thumb exist for the second. This suggests that treatment primarily affected her perfectionistic concerns, while her perfectionistic standards were relatively unaffected. This is not uncommon and might be related to the fact that CBT seems to primarily target the worries associated with perfectionism, while paying less attention to the standards themselves (Lloyd et al., 2015; Suh et al., 2019). In the case of Sara, this seemed like the best way forward given her previous experience of counseling where the focus on lowering standards made her drop out. However, her elevated level of perfectionistic standards could constitute a vulnerability factor in future situations, particularly the tendency to be demanding of herself, and would have been suitable to target in a continued treatment.

One aspect that was not addressed during treatment concerned relational patterns typically found among clients with personality disorders. Sara displayed behaviors and beliefs that are characteristic of both avoidant and dependent personality disorders, particularly feelings of inadequacy, sensitivity to criticism, and difficulties raising disagreements with others. Dimaggio et al. (2018) have found that such expressions are not uncommon among those who also score high on self‐report measures of perfectionism and that it could be an important factor to consider. In the current case illustration, the assessment did not include a review of possible personality disorders, but should have been investigated. For one thing, Sara was highly conscientious and compliant throughout treatment, which may have been a reflection of her strong need to be submissive and avoid any type of critique. Whether this affected the outcome is unclear, but might constitute factors that maintain her need to be perfect in the future and put her at risk of relapse.

In the end, not all of the content outlined by Egan et al. (2016) turned out to be relevant for Sara. Exploring her motivation to change received little attention except indirectly through the use of psychoeducation and functional analyses. In this case, further motivational interventions were not deemed essential, but had she struggled with the completion of homework assignments this might have been more important to address, such as through listing the pros and cons of changing her behavior. Meanwhile, behavioral experiments and expanding her life domains proved to be particularly useful. However, a number of interventions intended to target self‐criticism and increase self‐compassionate thinking were considered less essential, e.g., practicing how to respond to a self‐critical voice in writing. Likewise, given that Sara did not experience any difficulties related to time‐management issues or procrastination, interventions targeting such problems were not presented. Instead, making room for leisure and relying less on her schedule was seen as more important for her. When evaluating treatment herself, Sara seemed satisfied with her progress, while still recognizing that some problems remained. “I definitely feel less occupied worrying that I might make mistakes or won't be able to live up to other peoples' expectations. I also feel less stressed out and more in control. Yet, I understand that I'm still vulnerable, I understand that achievements and recognition is still important to me, and that I have to continue working on those issues in many situations, perhaps indefinitely.”

5. CLINICAL PRACTICES AND SUMMARY

Perfectionism is common among clients seeking help for mental distress. It is sometimes involved in a pre‐existing condition such as depression, but can also be a problem in itself (Egan et al., 2011). The current case illustration has described how CBT can be applied in relation to someone experiencing difficulties in both her interpersonal relationships and many everyday situations, highlighting the processes maintaining her problems and how these can be resolved. More specifically, the use of behavioral experiments targeting some of the cognitive biases and performance‐related behaviors have been demonstrated, for example, how to test the prediction that one needs to do tasks and assignments in a certain way to prevent making mistakes and avert a catastrophe. Overall, such interventions tend to increase the client's ability to respond more flexibly to the events she is experiencing and make her regard her own and other peoples' performance less black‐or‐white. Furthermore, by becoming more adaptive and less governed by personally imposed rules, the client is also able to expand her activity repertoire, which can result in a more balanced way of living while leaving room for leisure and relaxation.

A key point in using CBT for perfectionism is the importance of creating an individualized conceptualization of the client's ongoing problems. Thereby, a sensible rationale of maintaining processes is provided which can help motivate treatment and the need to target some of the behaviors that are preventing her to change. Along the same line, lowering standards in themselves does not have to be put forward to the client explicitly as this can often harm the therapeutic alliance and end treatment prematurely. Instead, it is up to the client to explore the benefits and costs of continuing her perfectionism through the use of psychoeducation, behavioral experiments, and cognitive restructuring, recognizing that there is more to life than just trying to be perfect.

Rozental A. Beyond perfect? A case illustration of working with perfectionism using cognitive behavior therapy. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76:2041–2054. 10.1002/jclp.23039

REFERENCES

- Antony, M. M. , & Swinson, R. P. (1998). When perfect isn't good enough: Strategies for coping with perfectionism. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dimaggio, G. , MacBeth, A. , Popolo, R. , Salvatore, G. , Perrini, F. , Raouna, A. , … Montano, A. (2018). The problem of overcontrol: Perfectionism, emotional inhibition, and personality disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 83, 71–78. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan, S. J. , Wade, T. D. , & Shafran, R. (2011). Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(2), 203–212. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan, S. J. , Wade, T. D. , Shafran, R. , & Antony, M. M. (2016). Cognitive‐behavioral treatment of perfectionism, New York, NY: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, P. L. (2020). Perfecting, belonging, and repairing: A dynamic‐relational approach to perfectionism. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 61(2), 101–110. 10.1037/cap0000209 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, P. L. , & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–470. 10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limburg, K. , Watson, H. J. , Hagger, M. S. , & Egan, S. J. (2017). The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(10), 1301–1326. 10.1002/jclp.22435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, S. , Schmidt, U. , Khondoker, M. , & Tchanturia, K. (2015). Can psychological interventions reduce perfectionism? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 43(6), 705–731. 10.1017/S1352465814000162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öst, L.‐G. (1987). Applied relaxation: Description of a coping technique and review of controlled studies. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 25(5), 397–409. 10.1016/0005-7967(87)90017-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental, A. , Shafran, R. , Wade, T. , Egan, S. , Nordgren, L. B. , Carlbring, P. , … Andersson, G. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of Internet‐Based Cognitive Behavior Therapy for perfectionism including an investigation of outcome predictors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 95, 79–86. 10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran, R. , Cooper, Z. , & Fairburn, C. G. (2002). Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive–behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 773–791. 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00059-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran, R. , Coughtrey, A. , & Kothari, R. (2016). New frontiers in the treatment of perfectionism. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 9(2), 156–170. 10.1521/ijct.2016.9.2.156 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shafran, R. , Egan, S. , & Wade, T. (2018). Overcoming perfectionism: A self‐help guide using scientifically supported cognitive behavioural techniques. London, UK: Robinson. [Google Scholar]

- Shafran, R. , Wade, T. D. , Egan, S. J. , Kothari, R. , Allcott‐Watson, H. , Carlbring, P. , … Andersson, G. (2017). Is the devil in the detail? A randomised controlled trial of guided internet‐based CBT for perfectionism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 95, 99–106. 10.1016/j.brat.2017.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoeber, J. (2017). The psychology of perfectionism: Theory, research, applications. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, H. , Sohn, H. , Kim, T. , & Lee, D. G. (2019). A review and meta‐analysis of perfectionism interventions: Comparing face‐to‐face with online modalities. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(4), 473–486. 10.1037/cou0000355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetterberg, M. , Carlbring, P. , Andersson, G. , Berg, M. , Shafran, R. , & Rozental, A. (2019). Internet‐based cognitive behavioral therapy of perfectionism: Comparing regular therapist support and support upon request. Internet Interventions, 17, 100237 10.1016/j.invent.2019.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]