Abstract

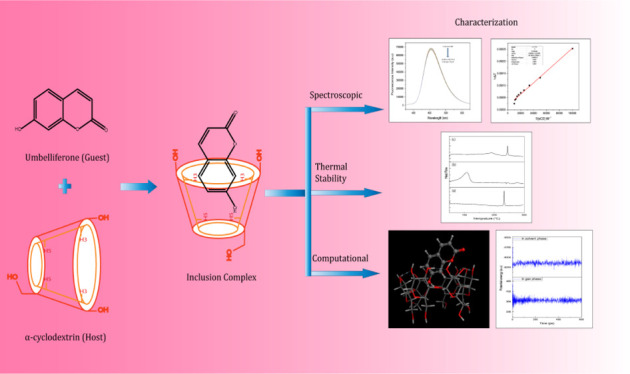

In this study, umbelliferone and α-cyclodextrin host molecules have been mixed up through a coprecipitation method to prepare a supramolecular complex to provide physical insights into the formation and stability of the inclusion complex (IC). The prepared hybrid was characterized by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry, DSC, and fluorescence spectroscopic studies. Job’s plot provides a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1 and the Benesi–Hildebrand double reciprocal plot gives binding constant values using fluorescence spectroscopic titrations and the ESI mass data support the experimental observations. The results of molecular modeling were systematically analyzed to validate the inclusion complexation. In preliminary computational screening, α-cyclodextrin IC of umbelliferone was found to be quite stable based on the docking score, binding free energies, and dynamic simulations. In addition, the results obtained from 1H NMR and FTIR spectroscopy studies supported the inclusion complexation phenomenon. The results obtained from computational studies were found to be consistent with the experimental data to ascertain the encapsulation of umbelliferone into α-cyclodextrin.

1. Introduction

In recent years, skin allergy and different cancers, such as basal and squamous cell carcinomas and malignant melanoma have become some of the most important health issues because of extensive exposure to sunlight as well as ultraviolet (UV) radiation.1,2 To tackle this problem, various UV-absorbing agents have been introduced as the formulations in cosmetic industries.3 It is important to keep in mind that the overall impact of biologically active ingredients through cosmetics with multiple product usage over a day in the skin has to be sufficiently low with a minimum side effect. Nowadays, sunscreen ingredients are produced by various metal nanoparticles (predominantly ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles) for active UVA and UVB protection of skin, which absorb, reflect, and scatter UV radiation, along with other organic molecules as UV absorbers, for example, avobenzone and sulisobenzone.4,5 However, there is an increasing concern regarding the adverse health and environmental effects of these sunscreen ingredients and, therefore, various researchers already have started to find safer alternatives, for example, by surface coating of hazardous nanomaterials with silica layers or by enclosing different organic UV absorbers within the framework of organosilica nanoparticles.6 The loaded UV filter molecules encapsulated in a supramolecular matrix could easily be synthesized and dispersed so that they can be shielded from constant damage by an external mechanical force.7

Owing to their wide range of photostability, excellent photosensitivity, and high color strength, organic dyes have attracted significant interest and been widely used in textiles, paints, inks, electronic devices, and metal oxide (TiO2) photocatalysis.8,9 Coumarin belongs to a chemical class of benzopyrones, which include further naturally occurring derivatives, such as umbelliferone (UMB) (7-hydroxycoumarin), aesculetin (6,7-dihydroxycoumarin), or herniarin (7-methoxycoumarin), showing a wide variety of potential biological activities, for example, lipid-lowering ability, anticarcinogenic activity, and HIV-inhibition activity.10,11 The odor-fixing properties and sweet, warm, and vanilla-like scent of coumarin make it a promising synthetic fragrance component or a natural ingredient of various essential oils and plant extracts, such as sweet woodruff, Tonka, or lavender, in a large number of cosmetic products.12,13

UMB, a coumarin-based molecule, has been extensively used as a sunscreen agent in cosmetics and optical brighteners in textiles.14 UMB is a 7-hydroxycoumarin that is a pharmacologically active agent and shows antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and free radical-scavenging activities.15,16 UMB has been generally introduced as the initial starting material for the preparation of more complex coumarin derivatives and is widely used as a synthon for a wider variety of coumarin-heterocycles with potential biological activity.17

Cyclodextrins are well-known cyclic oligosaccharides consisting of six, seven, or eight α-(1 → 4)-d-glucoside moieties, giving rise to α-, β-, and γ-CDs, respectively.18−20 Owing to their nontoxic nature and complexation ability, CDs are generally regarded as safe and have received widespread attention for application in food, agriculture, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical industries.21−23 Recently, various works have been carried out with different organic UV-absorbing agents with cyclodextrins, for example, Mori et al.24 shown that octylmethoxy cinnamate and avobenzone have been formulated with different cyclodextrins into cosmetic sunscreens. These kinds of chemical modifications through supramolecular complexation possibly will enhance the substance concentration in the upper skin layers by reducing its percutaneous penetration. Previously, a similar kind of inclusion complexation studies has been done by Meltida and Kumari and Wang et al. with UMB and βCD as well as HP-α-CD.25,26 Herein, we have designed three different inclusion complexes and, thereafter, different kinds of characterization techniques have been applied to check the formation of the inclusion complex. In this study, we report the synthesis and characterization of the UMB + αCD inclusion complex and our main objective was to determine the influence of complexation with αCD in improving thermal stability as well as photostability (Scheme 1).

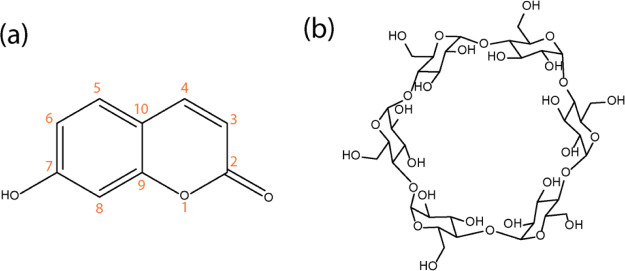

Scheme 1. Two-Dimensional Structure of (a) UMB and (b) α-Cyclodextrin.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

Both UMB and α-cyclodextrin were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Pvt. Ltd. (India). All reagents were of analytical reagent grade and were used without further purification (Table S1). Doubly distilled water was used in all experiments.

2.2. Instruments

All the fluorescence titrations were carried out on a bench top spectrofluorimeter from Photon Technologies International (PTI) QuantaMaster-40, USA. Solution-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments were performed on a Bruker AVANCE DRX 400 NMR spectrometer operating at 400 MHz for obtaining the 1H NMR spectra. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained using a PerkinElmer spectrometer with a resolution of 4 cm–1. All DSC spectra were recorded using a PerkinElmer Pyris DSC 6 with 1.2 mg of the sample in all cases by heating in the range of 30–300 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min under a N2 gas flow of 40 mL/min. All samples were prepared with spectroscopic grade KBr, which constituted a 100:1 ratio with respect to the total sample.

2.3. Sample Preparation

The inclusion complexation of UMB with αCD was prepared by applying the coprecipitation method.27 A solution of αCD (1.38 g) and UMB (0.2 g) was prepared in 25 mL of double-distilled water in a 1:1 molar ratio and stirred at 55 °C for 48 h. The resulting clear solution was evaporated to dryness. Then, the white precipitate was filtered cautiously and washed with ethanol and water four times to eliminate uncomplexed UMB and αCD. The resulting precipitate was then dried in a hot air oven at 50 °C for 12 h. The obtained inclusion complex was kept in a desiccator prior to analysis.

2.4. Preparation of 3D-Structures of UMB and α-Cyclodextrin

The crystal structures of UMB (CCDC code: 1139276) and αCD (CCDC code: 125105) were collected from Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC). The missing hydrogen atoms and atomic charges to CDs as well as UMB were added and energy minimization was carried out with force field MMFF94x and gradient 0.05 kcal·mol–1·Å–1 using MOE.2015 software.28 These structures were used as a starting point to perform the computational studies.

2.5. Molecular Docking and Simulations

In supramolecular chemistry, molecular docking is a computational process of searching for a guest that is able to fit both geometrically and energetically in the cavity of the host moiety.28,29 This is a process by which two molecules fit together in 3D space. The aim of docking is to predict the predominant binding mode for a guest with a host of a known three-dimensional structure. An established docking protocol for host–guest system implemented in MOE was applied. The docking was carried out with the default parameters, that is, with the triangle matcher method and ordered with the London ΔG scoring function. The top five produced poses were ranked as per their docking scores and saved in a separate database file in a .mdb format. The build-in scoring function of MOE, S-score, was used to predict the binding affinity (kcal·mol–1) of the optimized structure of the inclusion complex.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Job’s Plot

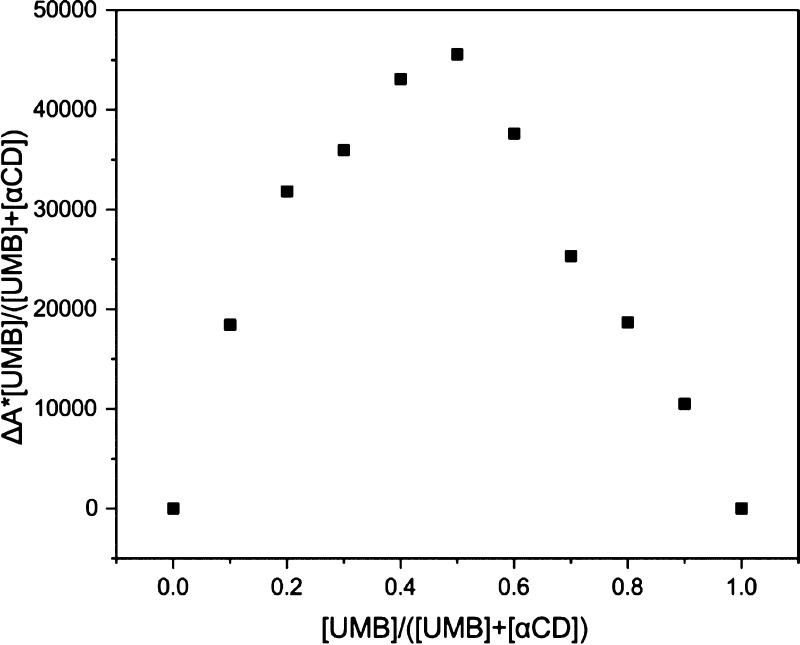

A very reliable continuous variation method also known as Job’s plot was performed in order to validate the stoichiometry of the inclusion complex.30 The sum of the concentrations of both components was kept constant ([UMB] + [αCD] = 1.0 × 10–4 M) and the molar fraction of UMB (R = [UMB]/([UMB] + [αCD])) varied from 0.0 to 1.0 (Table S2). In order to calculate the stoichiometry, the fluorescence emission intensity variations (F) of UMB were plotted versus the molar fraction (R).31Figure 1 illustrates the continuous variation spectra of the αCD/UMB system examined by fluorescence titrations.

Figure 1.

Fluorescence emission spectra of UMB by varying both host and guest such that the sum of the concentrations of both components was kept constant ([UMB] + [αCD] = 1.0 × 10–4 M).

The plot observed in Figure 2 showed the maximum at a molar fraction of about 0.5, indicating that the stoichiometry of the complex UMB + αCD was 1:1 in agreement with the linear plot obtained from the Benesi–Hildebrand method.

Figure 2.

Job’s plot of the UMB/αCD inclusion complex using fluorescence emission spectroscopy.

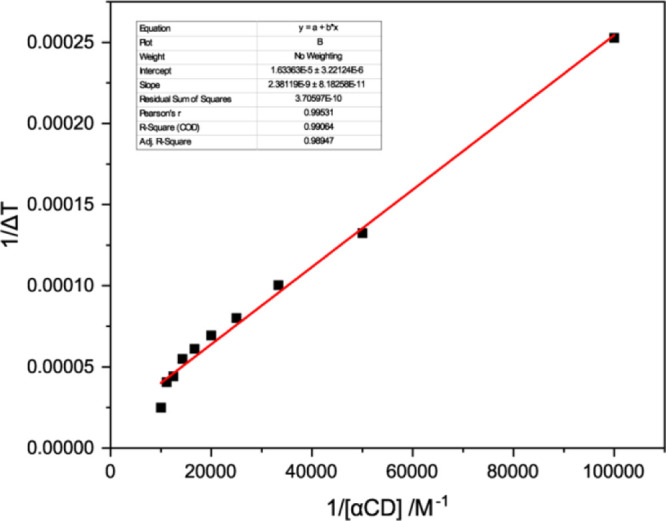

3.2. Association Constant Calculations

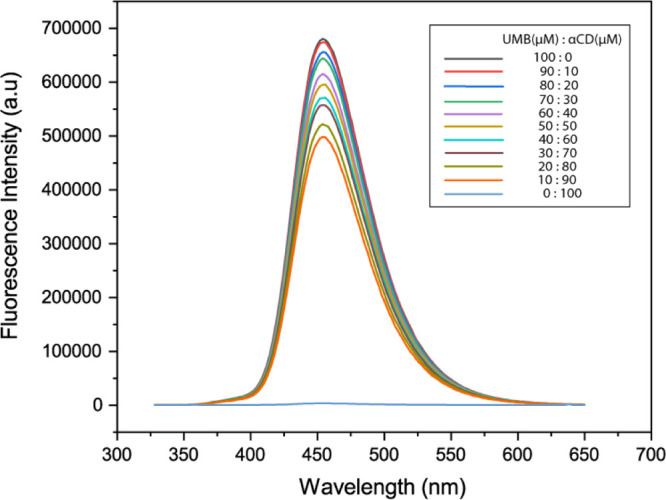

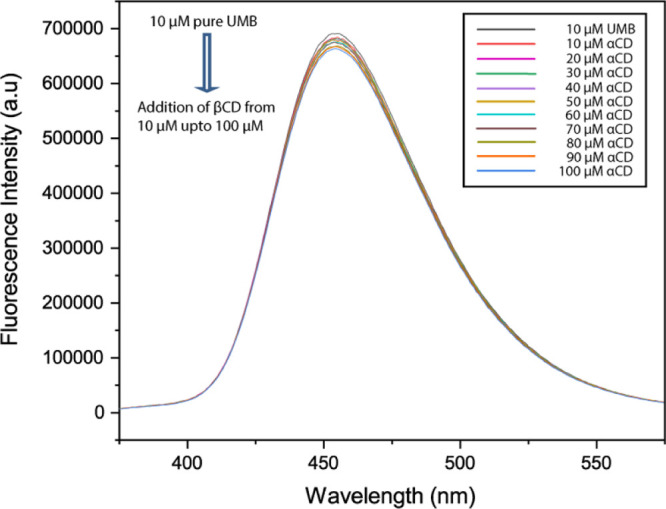

The stoichiometry and formation constant of the UMB and αCD complex was studied by using fluorescence emission titration.32 Association constants (Ka) of host–guest inclusion complexes were calculated using the modified Benesi–Hildebrand equation (eq 1) from the fluorescence experimental data. The addition of α-cyclodextrin to an aqueous solution of UMB resulted in a decrease of the measured fluorescence intensity. The fluorescence signal of UMB is highly sensitive to the addition of the αCD solution.

| 1 |

where F and Fo denote the fluorescence intensity of UMB on adding αCD and pure UMB, respectively. Fmax is the saturation fluorescence intensity. Ka is the association constant obtained by dividing the intercept by the slope. n is the binding stoichiometry between αCD and UMB.

The binding constant of the complexes assumed with the use of eq 1 can be verified by plotting the double reciprocal plot of 1/(Fo – F) versus 1/[αCD] (Table S3); this plot will be linear in the case of 1:1 complexation, but will be curved if higher-order complexes occur.33Figure 3 shows the double reciprocal plot, demonstrating the highly linear plot, with R2 = 0.9992, confirming 1:1 complexation for this αCD.

Figure 3.

Double reciprocal Benesi–Hildebrand plot of 1/(Fo – F) vs 1/[αCD] at 298.15 K.

Figure 4 depicts the fluorescence spectra of UMB with increasing concentration of αCD. There is a decrease in the fluorescence intensity of UMB with αCD addition, indicating the formation of an inclusion complex between UMB and αCD. From this fluorescence titration, we had estimated the binding constant shown in Table 1, using the intercept and slope, it was found to be 6.86 × 103 M–1 at 298.15 K and Gibbs free energy was −5.21 kcal·mol–1.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence spectra of UMB in the absence and presence of various concentrations of αCD at 298.2 K, where the initial concentration of UMB was 10 μM and the concentration of αCD was varied from 10, 20, 30 μM upto 100 μM.

Table 1. Stability Constant (Ka and log Ka) and Gibbs Free Energy Change (ΔG) at 298.15 K for the Inclusion Complexation of CDs with UMB Guest in Water (1 kcal = 4.2 kJ).

| host | guest | Ka (M–1) | log Ka | ΔG°/kcal mol–1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αCD | UMB | 6860 | 3.83 | –5.21 |

3.3. FTIR Spectral Analysis

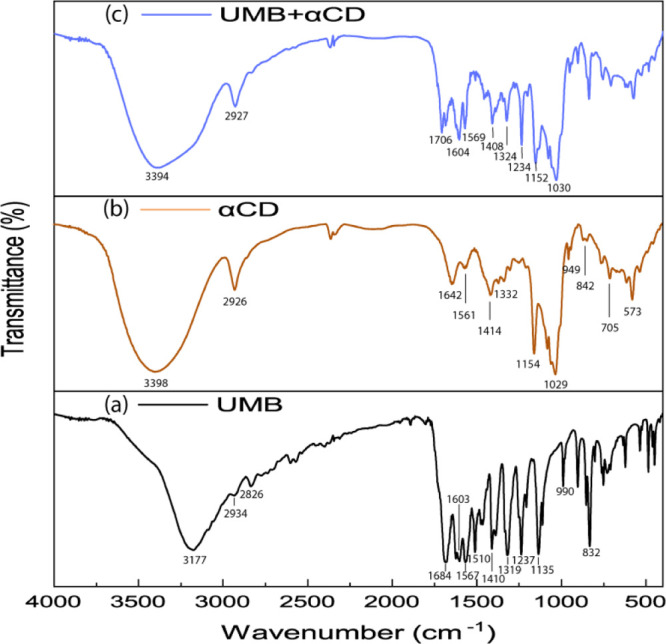

The solid inclusion complex formation is analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy. FTIR spectroscopy is used to confirm the formation of the solid inclusion complex by considering the deviation of the peak shape position and intensity.34Figure 5 depicts all the spectra of pure UMB, αCD, and the UMB + αCD inclusion complex. The FTIR spectrum of pure UMB disclosed typical absorption bands at 3177 cm–1 for phenolic (−O–H stretching), 1603 cm–1 for (C=O stretching), 1684, 1567, and 1510 cm–1 for (aromatic C=C stretching), and 1319 and 1135 cm–1 for (C–O–C stretching).35 In the case of αCD, stretching vibration of O–H at 3398 cm–1, stretching vibration of −C–H from −CH2 at 2926 cm–1, bending vibration of −C–H from −CH2, and bending vibration of O–H and C–O–C at 1416 and 1154 cm–1, respectively, were found. Stretching vibration of C–C–O and skeletal vibration involving α-1,4 linkage at 949 cm–1 appeared at 1129 cm–1.36 When, the UMB + αCD inclusion complex is formed, −O–H bond-stretching frequency of the hydroxyl group of cyclodextrin was observed at 3394 cm–1, the C=O group of lactone moiety got shifted to 1706 cm–1, the phenolic O–H part of UMB observed in pure guest at 3177 cm–1 has been diminished, and aromatic C=C stretching vibrations that appeared at 1684, 1567, and 1510 cm–1 in pure UMB are absent after inclusion complexation (Table S4). From the above data, it can be concluded that the aromatic part of UMB has been inserted into the cavity of α-cyclodextrin.

Figure 5.

FTIR spectra of (a) UMB, (b) αCD, and (c) UMB + αCD inclusion complex.

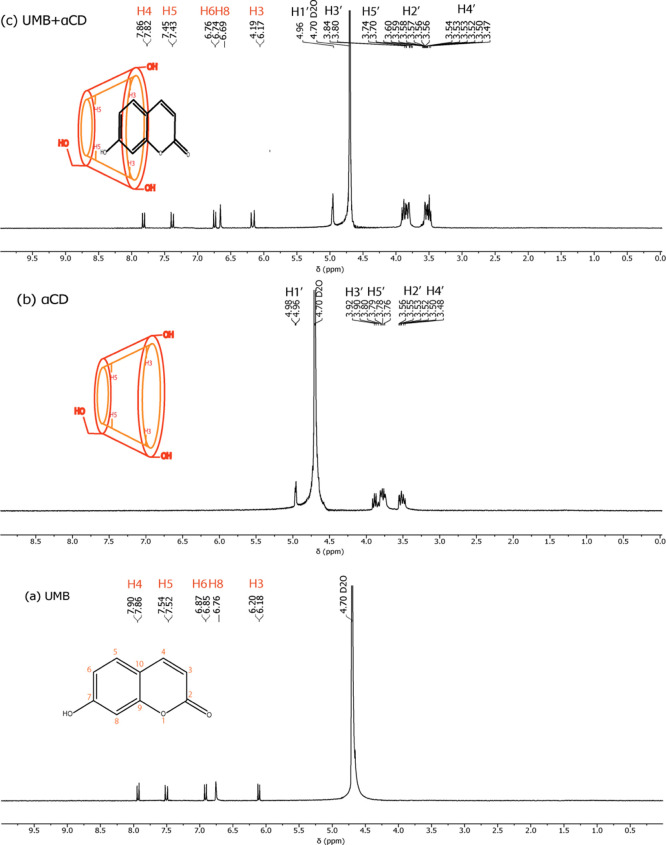

3.4. 1H NMR Studies

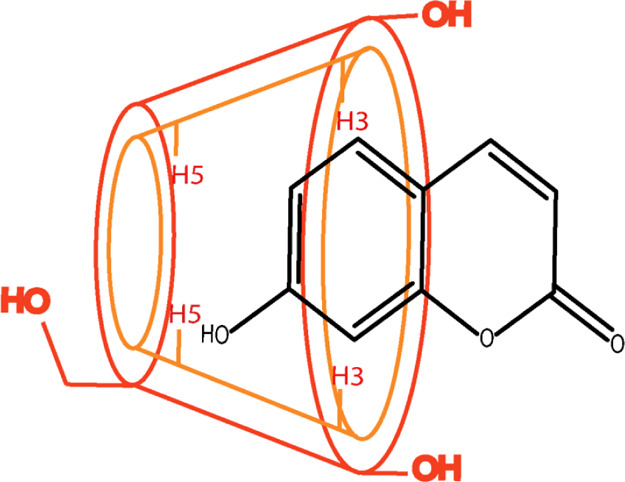

The 1H NMR spectra of UMB, αCD, and the inclusion complex (in D2O) are shown in Figure 6. In the spectrum of the UMB + αCD inclusion complex, appreciable chemical shift changes were observed for protons of UMB as well as αCD in the inclusion complex with respect to the spectra of the free UMB and αCD, respectively. The chemical shifts of the αCD protons in the absence and presence of UMB are listed in Table 2. From the spectra, it is observed that changes in the signals of H-1, H-2, and H-4 protons on the outer surface of αCD are negligible with Δδ values of −0.00, −0.03, and −0.04, respectively. However, complexation of a hydrophobic guest causes significant chemical shift changes of H-3 and H-5 protons that are present in the inner cavity of αCD,37,38 and in this case it was found to be an upfield shift of −0.10 and −0.06 ppm for H-3 and H-5 protons, respectively. It is to be mentioned that the chemical shift variation for H-3 was higher than that for H-5 after the formation of the inclusion complex.

Figure 6.

1H NMR spectra of (a) UMB, (b) αCD, and (c) UMB + αCD inclusion complex.

Table 2. 1H NMR Data for UMB in the UMB + αCD Complex in D2O.

| pure guest | inclusion complex | change in chemical shift | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| guest | position of protons | chemical shift (ppm) | chemical shift (ppm) (IC) | Δδ = (δIC – δpure) |

| H-3 | 6.18–6.20 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz) | 6.17–6.19 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz) | –0.01 | |

| H-4 | 7.86–7.90 (1H, d, J = 16 Hz) | 7.82–7.86 (1H, d, J = 16 Hz) | –0.04 | |

| UMB | H-5 | 7.52–7.54 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz) | 7.43–7.45 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz) | –0.09 |

| H-6 | 6.85–6.87 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz) | 6.74–6.76 (1H, d, J = 8 Hz) | –0.11 | |

| H-8 | 6.76 (1H, s) | 6.69 (1H, s) | –0.07 | |

| αCD | H-3′ | 3.90–3.92 (6H, m) | 3.80–3.84 (6H, m) | –0.10 |

| H-5′ | 3.76–3.80 (6H, m) | 3.70–3.74 (6H, m) | –0.06 |

To further explore the possible inclusion mode of UMB + αCD, we compared the 1H NMR spectrum of UMB in the absence and presence of αCD.39 Chemical shift changes for different protons in UMB with the inclusion complex are listed in Table 2. Here, it is observed that aromatic protons such as H-5, H-6, and H-8 are highly upfield shifted and found to be −0.09, −0.011, and −0.07 respectively. Based on these 1H NMR results, we deduced the aromatic group of UMB deeply inserted into the cavity of αCD and the possible inclusion modes for the UMB + αCD complex are illustrated in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2. Schematic Illustration of the UMB + αCD Inclusion Complex.

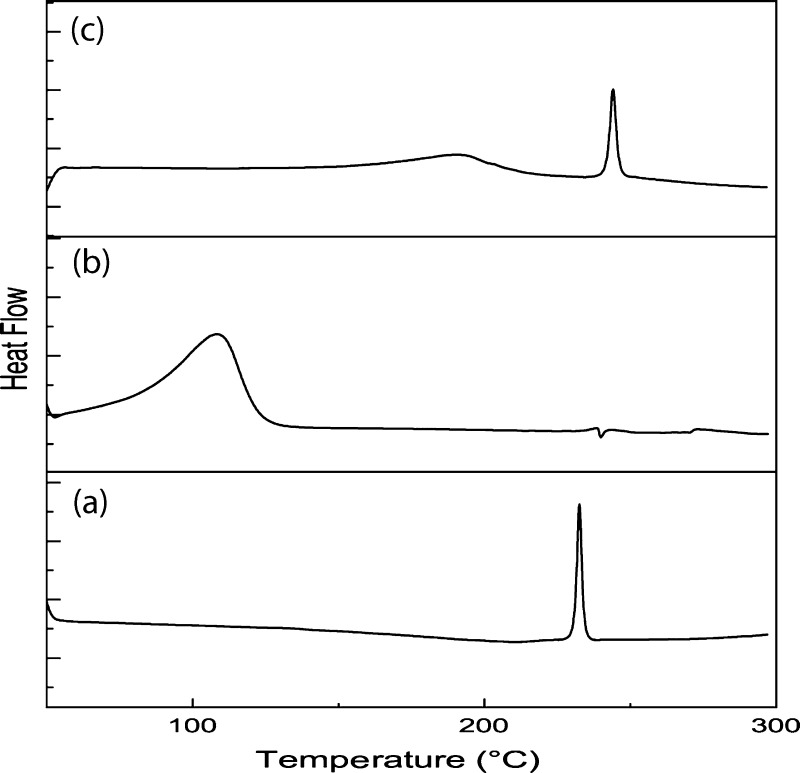

3.5. DSC Analysis

A further insight into the interaction of host, guest, and complexed state can be assigned via the DSC study.40 A shift or change in the intensity of the peak or disappearance of melting, boiling, and sublimation points is observed in DSC curves because of the inclusion of a drug in cyclodextrin. Thermogram of pure UMB {Figure 7a} exhibited a single endothermic peak in the temperature range of 30–300 °C.41,42 The peak appeared at around 233 °C was sharp and strong. Formation of this peak indicates the purity as well as crystalline character of UMB. Whereas, in the case of αCD, an endothermic peak appeared at around 108 °C, which corresponds to the release of water molecules bound with different energy in the cavity of cyclodextrin {Figure 7b}. When the inclusion complex was formed, the peak appeared at 233 °C in pure UMB got slightly shifted to a higher temperature of 244 °C {Figure 7c}. Therefore, from the comparison of the above three thermograms and their shifted peaks, it was elucidated that some weak interactions, which could be hydrogen bonding, van der Waals, or electrostatic interactions, occurred between UMB and αCD.

Figure 7.

DSC thermograms of (a) UMB, (b) αCD, and (c) UMB + αCD inclusion complex.

3.6. ESI-MS Studies

A suitable estimation of the relative gas-phase stabilities of the inclusion complex was evaluated by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS).43 In Figure S1, the peaks observed at m/z 681.56, 1135.96, and 1157.99 are related to the molecular ions, [UMB + αCD + H]+, and [UMB + αCD + Na]+, respectively.44 As can be seen from this figure, in the positive mode there are peaks centered at m/z 1157.99 (Table 3, Figure S1), which clearly denote the formation of the singly charged ions of the [UMB + αCD + Na]+ complex.

Table 3. ESI-MS Analysis of the Complexes with Calculated as Well as Experimental Mass Values.

| name of the complexes | calculated mass (a.u.) | experimental mass (a.u.) |

|---|---|---|

| [UMB + αCD + H]+ | 1134.98 | 1135.96 |

| [UMB + αCD + Na]+ | 1157.98 | 1157.99 |

3.7. Molecular Docking Studies

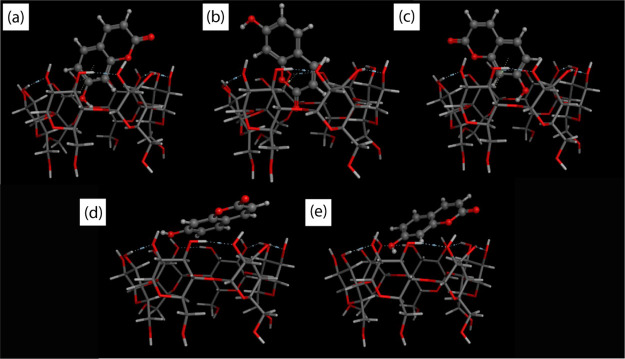

In recent years, the molecular docking has been extensively used to predict the bound conformations of CD and various drug molecules.45 The docking has been carried out for five different poses as shown in Figure 8. Docking results revealed the structural orientation of UMB inside the cavity of αCD as well as the lowest energy structure of the UMB + αCD inclusion complex.46

Figure 8.

Top best five conformational models of the UMB + αCD inclusion complex from (a) to (e) based on their binding affinity analyzed using MOE.2015 molecular docking software.

The computationally calculated binding affinities of the first five energy conformers of the UMB + αCD inclusion complex were −3.60, −3.59, −3.47, −3.42, and −3.42 kcal·mol–1, respectively, which were very near to the experimentally measured values (Table 4). Docking results demonstrate that the UMB was not completely embedded into the αCD cavities in all poses because of its small cavity size. For the first two poses, that is, Figure 9a,b, the binding affinity was quite similar and the change was about 0.01 kcal·mol–1. However, their structural orientation was totally different. In the first pose, the lactone moiety was located at the wider side of the αCD cavities but in the second case, the aromatic part came closer to the wider side of the αCD cavity, which was also supported by various spectroscopic methods, such as 1H NMR, FTIR, and so forth. However, in this work, only five conformations of optimized inclusion complexes based on their binding affinity have been studied and showed. If someone closely looks at the five conformations, it can be observed that Figure 8d,e are the conformations with least binding affinity and subsequently are not being encapsulated in the cavity of αCD. Therefore, the molecular docking and free energy calculation results suggested that UMB bound to αCD with both hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions.

Table 4. Binding Affinity of UMB + αCD in Different Poses Obtained from Molecular Docking.

| ligand with receptor (UMB + αCD) | binding affinity(ΔG) in kcal·mol–1 | rmsd_refine |

|---|---|---|

| pose 1 | –3.60 | 1.96 |

| pose 2 | –3.59 | 0.73 |

| pose 3 | –3.47 | 1.60 |

| pose 4 | –3.42 | 1.80 |

| pose 5 | –3.42 | 1.07 |

Figure 9.

Evaluation of potential energy of the complex as a function of time (a) in gas phase (b) in solvent phase.

3.8. Potential Energy Calculations of the Inclusion Complex

Potential energy calculations were carried out in order to obtain some information about the geometry and stability of the host–guest complex and to find the intermolecular interaction in αCD and UMB inclusion complexation.47 ΔE of the complexation was calculated for the minimum energy mode according to eq 2 and the data of EComplex, EHost + EGuest, and ΔE are listed in Table 4. This potential energy term (E) is actually a summation of various different energy terms and can be stated as eq 3.

| 2 |

| 3 |

where, Estr, Eang, Estb, Eoop, Etor, EvdW, Eele, and Esol are potential energy components for bond stretching, bond angle, stretching bending, out of plane bending, dihedral torsional, van der Waals, electrostatic, and solvation energies, respectively.48

The energies of the complex and its different components are summarized in Tables 5 and S5. As seen from the table, all the other energy components are unaltered but it is the van der Waals (ΔEvdW) and electrostatic (ΔEele) energies that are responsible for the complexation. The host–guest complexation in the gas phase is driven predominantly by vdW interactions. When the inclusion complex is formed, change in vdW energy, that is, ΔEvdW = −12.186 kcal·mol–1 is much lower than ΔEele = −7.839 kcal·mol–1, indicating the vdW forces play a pivotal role in the formation of UMB/αCD in an aqueous environment.

Table 5. Potential Energy of αCD (EHost), UMB (EGuest), Inclusion Complex (EComplex), and Change in Potential Energy (ΔE).

| inclusion complex | EHost (kcal·mol–1) | EGuest (kcal·mol–1) | EComplex (kcal·mol–1) | ΔE (kcal·mol–1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UMB + αCD | 602.083 | 46.778 | 605.615 | –43.246 |

3.9. Dynamic Simulations

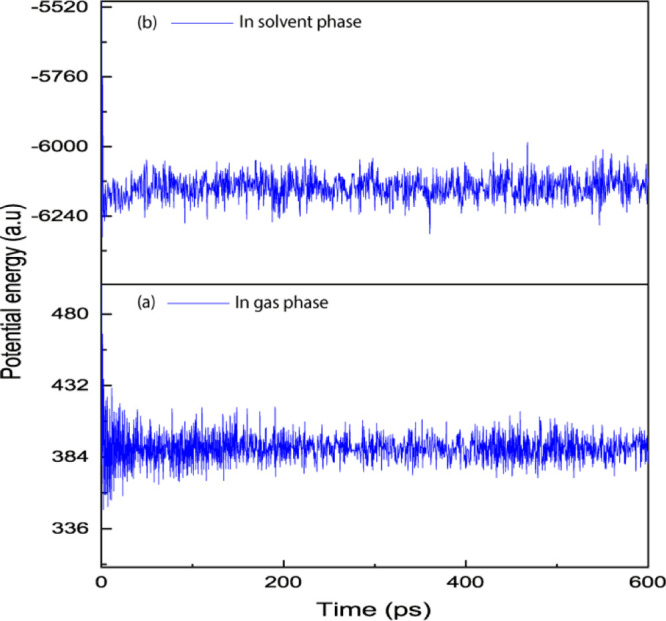

In this study, we used molecular dynamics to calculate the stability of the UMB and αCD inclusion complex equilibrium.49 The rigid microenvironment of the guest inside the host cavity and the stability of the complexes have been discussed using MD simulations based on the potential energy change with time.

Figure 9 shows the plot of potential energy versus time (ps) obtained through MD simulations for the complex structure in the gas phase as well as in the solvent phase. For complex UMB + αCD in the gas phase, we noticed a potential energy change from 586.201 to 385.245 kcal·mol–1 during first 100 ps; it also showed a slight variation of potential energy: 385.245 to 387.618 kcal·mol–1 in the second part of the interval between 100 and 600 ps. The binary inclusion complex of UMB in the gas phase showed an initial potential energy value and high fluctuations in the potential energy, but latter got stabilized after 100 ps of time. In the solvent phase, we noted that the UMB + αCD complex has a potential energy change from −5021.233 to −6190.101 kcal·mol–1 during first 100 ps, we also noticed a variation of potential energy: −6190.101 to −6122.078 kcal·mol–1 in the second part of the interval between 100 and 600 ps.50 Therefore, we observed that the complex becomes stable after 100 ps in both phases. The potential energy deviance of the complex was less for the inclusion complex in the solvent phase compared to the inclusion complex in the gas phase indicating the better stability of the supramolecular inclusion complex in the solvent phase.

4. Conclusions

In the present study, UMB + αCD was designed, synthesized, and characterized by using 1H NMR, FTIR, and ESI-MS. Job’s plot was used to confirm the stoichiometry of the inclusion complex. From the FTIR and NMR data, it is confirmed that the aromatic part has been inserted into the α-cyclodextrin cavity. Differential scanning calorimetric value for the inclusion complex confirms that it is thermally stable upto 244 °C. Thermodynamic parameters like the binding constant have been found to be favorable for stable inclusion complexation. From the molecular docking study, it is observed that when UMB inserted through the aromatic part, it showed the highest binding affinity compared to the rest of the four poses, which confirmed the preferential encapsulation and the geometry of the inclusion complex obtained from 1H NMR experiments. Thus, molecular docking as well as dynamic simulations also support the experimental evidence. Thus, the overall study concluded that the UMB-α–cyclodextrin supramolecular hybrid could lead to further developments of sunscreen agents.

Acknowledgments

N.R. acknowledges UGC-NFSC for Junior Research fellowship {ref. no. 2219/(CSIR-UGC NET JUNE 2019)}. Corresponding author M.N.R. is very much thankful to UGC for receiving one time Grant of seven lakhs from UGC-BSR (ref. no. F.4-10/2010).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c04716.

Detailed descriptions of all the chemicals used, Job’s plot table, association constant data, ESI-MS spectra of the inclusion complexes, and potential energy calculations of both inclusion complexes using computational studies (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kockler J.; Oelgemöller M.; Robertson S.; Glass B. D. Photostability of sunscreens. J. Photochem. Photobiol., C 2012, 13, 91–110. 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2011.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afonso S.; Horita K.; Sousa e Silva J. P.; Almeida I. F.; Amaral M. H.; Lobão P. A.; Costa P. C.; Miranda M. S.; Esteves da Silva J. C. G.; Sousa Lobo J. M. Photodegradation of avobenzone: Stabilization effect of antioxidants. J. Photochem. Photobiol., C 2014, 140, 36–40. 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiefel C.; Schubert T.; Morlock G. E. Bioprofiling of Cosmetics with Focus on Streamlined Coumarin Analysis. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 5242–5250. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.; Wang X.; Zhan Y.; Xu Z.; Xu Z.; Feng X.; Li S.; Xu H. A Dual Network Hydrogel Sunscreen Based on Poly-γ-glutamic Acid/Tannic Acid Demonstrates Excellent Anti-UV, Self-Recovery, and Skin-Integration Capacities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 37502–37512. 10.1021/acsami.9b14538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsella M.; d’Alessandro N.; Lanterna A. E.; Scaiano J. C. Improving the Sunscreen Properties of TiO2 through an Understanding of Its Catalytic Properties. ACS Omega 2016, 1, 464–469. 10.1021/acsomega.6b00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knežević N. Ž.; Ilić N.; Dokić V.; Petrović R.; Janaćković D. Mesoporous Silica and Organosilica Nanomaterials as UV-Blocking Agents. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 20231–20236. 10.1021/acsami.8b04635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Qian L.; Feng Y.; Feng J.; Tang P.; Yang L. Co-intercalation of Acid Red 337 and a UV Absorbent into Layered Double Hydroxides: Enhancement of Photostability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 20603–20611. 10.1021/am506696k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Qian L.; Feng Y.; Tang P.; Li D. Acid Blue 129 and Salicylate Cointercalated Layered Double Hydroxides: Assembly, Characterization, and Photostability. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 17961–17967. 10.1021/ie502893f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leandri V.; Gardner J. M.; Jonsson M. Coumarin as a Quantitative Probe for Hydroxyl Radical Formation in Heterogeneous Photocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 6667–6674. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b00337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krauter C. M.; Möhring J.; Buckup T.; Pernpointner M.; Motzkus M. Ultrafast branching in the excited state of coumarin and umbelliferone. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 17846–17861. 10.1039/c3cp52719k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V.; Al-Abbasi F. A.; Verma A.; Mujeeb M.; Anwar F. Umbelliferone β-D-galactopyranoside Exerts Anti-inflammatory Effect by Attenuating COX-1 and COX-2. Toxicol. Res. 2015, 4, 1072–1084. 10.1039/c5tx00095e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Telange D. R.; Nirgulkar S. B.; Umekar M. J.; Patil A. T.; Pethe A. M.; Bali N. R. Enhanced transdermal permeation and anti-inflammatory potential of phospholipids complex-loaded matrix film of umbelliferone: Formulation development, physico-chemical and functional characterization. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 131, 23–38. 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L.; Li X.-z.; Yan Z.-q.; Guo H.-r.; Qin B. Phytotoxicity of umbelliferone and its analogs: Structure-activity relationships and action mechanisms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 97, 272–277. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazimba O. Umbelliferone: Sources, chemistry and bioactivities review. Bull. Fac. Pharm. (Cairo Univ.) 2017, 55, 223–232. 10.1016/j.bfopcu.2017.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar F.; Al-Abbasi F. A.; Bhatt P. C.; Ahmad A.; Sethi N.; Kumar V. Umbelliferone β-d-galactopyranoside inhibits chemically induced renal carcinogenesis via alteration of oxidative stress, hyperproliferation and inflammation: possible role of NF-kB. Toxicol. Res. 2015, 4, 1308–1323. 10.1039/c5tx00146c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Real M.; Gámiz B.; López-Cabeza R.; Celis R. Sorption, persistence, and leaching of the allelochemical umbelliferone in soils treated with nanoengineered sorbents. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9764. 10.1038/s41598-019-46031-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarsenkar A.; Guntuku L.; Prajapti S. K.; Guggilapu S. D.; Sonar R.; Vegi G. M. N.; Babu B. N. Umbelliferone–oxindole hybrids as novel apoptosis inducing agents. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 12604–12610. 10.1039/c7nj02578e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster M. E.; Loftsson T. Cyclodextrins as pharmaceutical solubilizers. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2007, 59, 645–666. 10.1016/j.addr.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M. N.; Saha S.; Barman S.; Ekka D. Host–guest inclusion complexes of RNA nucleosides inside aqueous cyclodextrins explored by physicochemical and spectroscopic methods. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 8881–8891. 10.1039/c5ra24102b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceborska M. Interactions of Native Cyclodextrins with Biorelevant Molecules in the Solid State: A Review. Curr. Org. Chem. 2014, 18, 1878–1885. 10.2174/1385272819666140527232228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bomzan P.; Roy N.; Sharma A.; Rai V.; Ghosh S.; Kumar A.; Roy M. N. Molecular Encapsulation Study of Indole-3-methanol in Cyclodextrins: Effect on Antimicrobial Activity and Cytotoxicity. J. Mol. Struct. 2021, 1225, 129093. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R.; Roy K.; Subba A.; Mandal P.; Basak S.; Kundu M.; Roy M. N. Case to case study for exploring inclusion complexes of an anti-diabetic alkaloid with α and β cyclodextrin molecules for sustained Dischargement. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1200, 126988. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2019.126988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B.; Hua S.; Liu J. Cyclodextrin-based delivery systems for chemotherapeutic anticancer drugs: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 232, 115805. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T.; Tsuchiya R.; Doi M.; Nagatani N.; Tanaka T. Solubilization of ultraviolet absorbers by cyclodextrin and their potential application in cosmetics. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2019, 93, 91–96. 10.1007/s10847-018-0846-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metilda G. M.; Kumari J. P. Preparation and Characterization of Umbelliferone and Hydroxy Propyl α-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex. Indian J. Appl. Res. 2015, 5, 158–160. [Google Scholar]

- Wang E.; Chen G.; Han C. Crystal Structures of β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes with 7-Hydroxycoumarin and 4-Hydroxycoumarin and Substituent Effects on Inclusion Geometry. Chin. J. Chem. 2011, 29, 617–622. 10.1002/cjoc.201190131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahaman H.; Roy N.; Roy A.; Ray S.; Roy M. N. Exploring Existence of Host-Guest Inclusion Complex of β-Cyclodextrin of a Biologically Active Compound with the Manifestation of Diverse Interactions. Emerg. Sci. J. 2018, 2, 251–260. 10.28991/esj-2018-01149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Q.; Li T.; Wang X.; Chu W.; Cai M.; Xie J.; Ni H. The mechanism of bensulfuronmethyl complexation with β-cyclodextrin and 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and efect on soil adsorption and bio-activity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1882. 10.1038/s41598-018-38234-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeoye O.; Conceição J.; Serra P. A.; Bento da Silva A.; Guedes R. C.; Corvo M. C.; Aguiar-Ricardo A.; Jicsinszky L.; Casimiro T.; Cabral-Marques H. Cyclodextrin solubilization and complexation of antiretroviral drug lopinavir: In silico prediction; Effects of derivatization, molar ratio and preparation method. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 227, 115287. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y.; Pang Y.; Guo Y.; Ren Y.; Wang F.; Liao X.; Yang B. Host-guest inclusion systems of daidzein with 2-hydroxypropyl-bcyclodextrin (HP-β-CD) and sulfobutyl ether-b-cyclodextrin (SBE-βCD): Preparation, binding behaviors and water solubility. J. Mol. Struct. 2016, 1118, 307–315. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2016.04.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shan P.-H.; Zhao J.; Deng X.-Y.; Lin R.-L.; Bian B.; Tao Z.; Xiao X.; Liu J.-X. Selective recognition and determination of phenylalanine by a fluorescent probe based on cucurbit[8]uril and palmatine. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1104, 164–171. 10.1016/j.aca.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favrelle A.; Gouhier G.; Guillen F.; Martin C.; Mofaddel N.; Petit S.; Mundy K. M.; Pitre S. P.; Wagner B. D. Structure–Binding Effects: Comparative Binding of 2-Anilino-6-naphthalenesulfonate by a Series of Alkyl- and Hydroxyalkyl-Substituted β-Cyclodextrins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 12921–12930. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b07157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida T.; Iwamoto T.; Fujino Y.; Tohnai N.; Miyata M.; Akashi M. Strong Guest Binding by Cyclodextrin Hosts in Competing Nonpolar Solvents and the Unique Crystalline Structure. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4570–4573. 10.1021/ol2017627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy N.; Ghosh R.; Das K.; Roy D.; Ghosh T.; Roy M. N. Study to synthesize and characterize host-guest encapsulation of antidiabetic drug (TgC) and hydroxy propyl-b-cyclodextrin augmenting the antidiabetic applicability in biological system. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1179, 642–650. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.11.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nath M.; Jairath R.; Eng G.; Song X.; Kumar A. New diorganotin(IV) derivatives of 7-hydroxycoumarin (umbelliferone) and their adducts with 1,10-phenanthroline. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2005, 61, 3155–3161. 10.1016/j.saa.2004.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telange D. R.; Nirgulkar S. B.; Umekar M. J.; Patil A. T.; Pethe A. M.; Bali N. R. Enhanced transdermal permeation and anti-inflammatory potential of phospholipids complex-loaded matrix film of umbelliferone: Formulation development, physico-chemical and functional characterization. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 131, 23–38. 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta A.; Roy N.; Das K.; Roy D.; Ghosh R.; Roy M. N. Synthesis and Characterization of Host Guest Inclusion Complexes of Cyclodextrin Molecules with Theophylline by Diverse Methodologies. Emerg. Sci. J. 2020, 4, 52–72. 10.28991/esj-2020-01210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos R. G.; Moura Bordado J. C.; Mateus M. M. 1H-NMR dataset for hydroxycoumarins–Aesculetin, 4-Methylumbelliferone, and umbelliferone. Data Brief 2016, 8, 308–311. 10.1016/j.dib.2016.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arza C. R.; Froimowicz P.; Ishida H. Smart chemical design incorporating umbelliferone as natural renewable resource toward the preparation of thermally stable thermosets materials based on benzoxazine chemistry. RSC Adv. 2005, 5, 97855–97861. 10.1039/C5RA18357J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajbanshi B.; Dutta A.; Mahato B.; Roy D.; Maiti D. K.; Bhattacharyya S.; Roy M. N. Study to explore host guest inclusion complexes of vitamin B1 with CD molecules for enhancing stability and innovative application in biological system. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 298, 111952. 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111952. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Froimowicz P.; Rodriguez Arza C.; Ohashi S.; Ishida H. Tailor-Made and Chemically Designed Synthesis of Coumarin-Containing Benzoxazines and Their Reactivity Study Toward Their Thermosets. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 1428–1435. 10.1002/pola.27994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lacatusu I.; Badea N.; Murariu A.; Oprea O.; Bojin D.; Meghea A. Antioxidant Activity of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles Loaded with Umbelliferone. Soft Mater. 2013, 11, 75–84. 10.1080/1539445x.2011.582914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das K.; Datta B.; Rajbanshi B.; Roy M. N. Evidences for Inclusion and Encapsulation of an Ionic liquid with β-CD and 18-C-6 in Aqueous Environments by Physicochemical Investigation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 1679–1694. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b11274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiefel C.; Schubert T.; Morlock G. E. Bioprofiling of Cosmetics with Focus on Streamlined Coumarin Analysis. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 5242–5250. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy N.; Bomzan P.; Nath Roy M. Probing Host-Guest inclusion complexes of Ambroxol Hydrochloride with α- & β-Cyclodextrins by physicochemical contrivance subsequently optimized by molecular modeling simulations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 748, 137372. 10.1016/j.cplett.2020.137372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nafie G.; Vitale G.; Carbognani Ortega L.; Nassar N. N. Nanopyroxene grafting with β-Cyclodextrin monomer for wastewater applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 42393–42407. 10.1021/acsami.7b13677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismahan L.; Leila N.; Fatiha M.; Abdelkrim G.; Mouna C.; Nada B.; Brahim H. Computational study of inclusion complex of l-Glutamine/beta-Cycldextrin: Electronic and intermolecular interactions investigations. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1206, 127740. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.127740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akae Y.; Koyama Y.; Sogawa H.; Hayashi Y.; Kawauchi S.; Kuwata S.; Takata T. Structural Analysis and Inclusion Mechanism of Native and Permethylated aCyclodextrin-Based Rotaxanes Containing Alkylene Axles. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22, 5335–5341. 10.1002/chem.201504882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaube U.; Chhatbar D.; Bhatt H. 3D-QSAR, molecular dynamics simulations and molecular docking studies of benzoxazepine moiety as mTOR inhibitor for the treatment of lung cancer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 864–874. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.12.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud I.; Melkemi N.; Salah T.; Ghalem S. Combined QSAR, molecular docking and molecular dynamics study on new Acetylcholinesterase and Butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2018, 74, 304–326. 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.