The review of the differences and similarities in the different case definitions for myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME)/chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) by Lim and Son [1] deserves appreciation. Based on their analysis the authors acknowledge the “distinct view of ME and CFS” [2] and recognize four categories of case definitions: ME, ME/CFS, CFS [3] and Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disorder (SEID) [4].

Indeed these labels reflect very different case definitions [5]. According to Lim and Son [1] the first category comprises two ‘ME’ case definitions: ME (Ramsay) [6] and ME according to the International Case Criteria (ME-ICC) [7]. However as can be deduced from Table 2 [1], ME [6] and ME-ICC [7] are two distinct clinical entities [8].

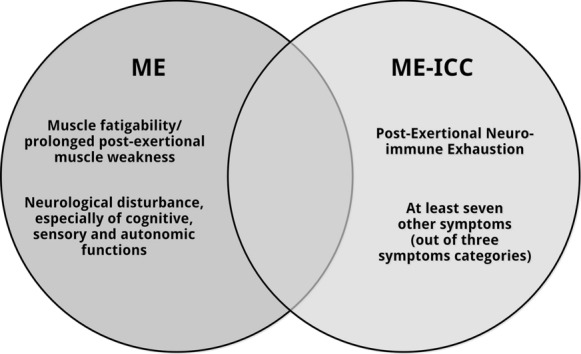

ME (Ramsay) [6] is a neuromuscular disease. The discriminative symptom of ME is muscle fatiguability/prolonged muscle weakness following trivial exertion. Ramsay states [9]: “[I]n my opinion a diagnosis should not be made without it”. Muscle fatigability is accompanied by “neurological disturbance, especially of cognitive, autonomic and sensory functions” [6]. So, in essence the case definition of ME (Ramsay) [6] is very simple [10] and requires two (types of) symptoms: muscle fatigability/post-exertional muscle weakness and specific neurological symptoms. “Other characteristics include [..] a prolonged relapsing course and variation in intensity of symptoms within and between episodes, tending to chronicity.” [6].

In contrast, the ME-ICC case definition [7] is much more complex. The diagnosis ME-ICC requires post-exertional neuro-immune exhaustion (mandatory symptom), at least three symptoms related to neurological impairments; at least three symptoms related to immune, gastro-intestinal, and genitourinary impairments; and at least one symptom related to energy production or transportation impairments [7].

The case criteria of ME [6] and ME-ICC [7] define two very different patient groups. Muscle fatigability/long-lasting post-exertional muscle weakness, a hallmark feature of ME, is not required to be qualified as ME-ICC [7] patient. Symptoms indicating autonomic, sensory, and/or cognitive dysfunction, also mandatory for the diagnosis ME [6], are not required to meet the ME-ICC [7] ‘neurological impairments’ criterion. The diagnosis ME [6] requires only two type of symptoms (muscle fatigability/post-exertional muscle weakness and “neurological disturbance”), but the polythetic definition of ME-ICC [7] requires a patient to have at least 8 symptoms. In essence, the case criteria of ME (Ramsay) and ME-ICC are not interchangeable (Fig. 1) [8].

Fig. 1.

ME (Ramsay) and ME-ICC (7): two different clinical entities

Finally, it is important to note that, in contrast with Table 2 [1], ME [6] is often but not always triggered by an infection and that ME requires at least four symptoms: muscle fatigability/prolonged post-exertional muscle weakness and three neurological symptoms indicative of cognitive, autonomic and sensory dysfunction.

In conclusion, ME (Ramsay) [6], a neuromuscular disease, is not comparable to ME-ICC [7]. ME [6], ME-ICC [7], ME/CFS, CFS [3] and SEID [4] are distinct clinical entities with partial overlap. So solving the current confusion with regard to case definitions requires a clear distinction between ME [6], ME-ICC [7], ME/CFS, CFS [3] and SEID [4].

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to Dr. Ramsay, Dr. Dowsett, Dr. Acheson and various others who dedicated their professional career to ME.

Abbreviations

- ME

Myalgic encephalomyelitis

- CFS

Chronic fatigue syndrome

- SEID

Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disorder

- ME-ICC

ME as defined by the International Case Criteria

Authors’ contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding.

Availability of data and materials

All data related to this study are available in the public domain.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

There are no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lim EJ, Son CG. Review of case definitions for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) J Transl Med. 2020;18:289. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02455-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Twisk FNM. Myalgic encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and systemic exertion intolerance disease: three distinct clinical entities. Challenges. 2018;9(1):19. doi: 10.3390/challe9010019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuda K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe M, Dobbins JG, Komaroff AL. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(12):953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine . Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: redefining an illness. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine/National Academy of Medicine; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Twisk FNM. Replacing Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome with systemic exercise intolerance disease is not the way forward. Diagnostics (Basel) 2016 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics6010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dowsett EG, Ramsay AM, McCartney RA, Bell EJ. Myalgic encephalomyelitis—a persistent enteroviral infection? Postgrad Med J. 1990;66(777):526–530. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.777.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, de Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, Mitchell T, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: international consensus criteria. J Intern Med. 2011;270(4):327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Twisk FNM. Myalgic encephalomyelitis or what? The International Consensus Criteria. Diagnostics (Basel) 2018 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics9010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramsay AM. Postviral fatigue syndrome—the saga of Royal Free Disease. 1. London (for the Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Association): Gower Medical Publishing; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Twisk FNM. Myalgic encephalomyelitis or what? An operational definition. Diagnostics (Basel) 2018 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics8030064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data related to this study are available in the public domain.