Abstract

Background

Globally, about 50 million people were living with dementia in 2015, with this number projected to triple by 2050. With no cure or effective treatment currently insight, it is vital that factors are identified which will help prevent or delay both age-related and pathological cognitive decline and dementia. Observational data have suggested that hearing loss is a potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia, but no conclusive evidence from randomised controlled trials is currently available.

Methods

The HearCog trial is a 24-month, randomised, controlled clinical trial aimed at determining whether a hearing loss intervention can delay or arrest the cognitive decline. We will randomise 180 older adults with hearing loss and mild cognitive impairment to a hearing aid or control group to determine if the fitting of hearing aids decreases the 12-month rate of cognitive decline compared with the control group. In addition, we will also determine if the expected clinical gains achieved after 12 months can be sustained over an additional 12 months and if losses experienced through the non-correction of hearing loss can be reversed with the fitting of hearing aids after 12 months.

Discussion

The trial will also explore the cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared to the control arm and the impact of hearing aids on anxiety, depression, physical health and quality of life. The results of this trial will clarify whether the systematic correction of hearing loss benefits cognition in older adults at risk of cognitive decline. We anticipate that our findings will have implications for clinical practice and health policy development.

Trial registration

Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR: 12618001278224), registered on 30.07.2018.

Keywords: Hearing loss, Hearing aids, Dementia, Depression, Frailty, Cognition, Cognitive decline

Background

Hearing loss is the second highest cause of disability in the world, affecting 466 million people, with 90% of cases being due to age-related hearing loss (ARHL) [1]. ARHL is a highly prevalent form of sensory impairment in later life, affecting 40 to 45% of people aged 65 years and 83% of those aged 70 years or above [2]. ARHL increases the risk of mental health problems [3], frailty [4], cognitive impairment [5] and dementia [6].

Currently, more than 50 million people are living with dementia, and this is projected to reach 75.63 million in 2030 and 135.46 million in 2050 [7]. According to the Lancet Dementia Taskforce, of the many risk factors that contribute to dementia, hearing loss could account for 8% of all dementia cases [8]. Developing effective strategies to prevent dementia has become a global health priority, with projections suggesting that the total number of people living with dementia could be reduced by 13% if the onset of symptoms could be delayed by two years or more [9].

Australian data from the Health In Men Study showed that in a sample of 37,898 older men, the hazard of dementia associated with hearing impairment was 1.69 (95%CI = 1.54, 1.85) [10]. In addition, a systematic review of 14 prospective studies showed that hearing loss was associated with a 49% (95%CI 30–67%) increase in the hazard of dementia [10]. Whilst this data shows a clear association between hearing loss and cognitive impairment, a causal relationship cannot be definitively determined, and it is currently not known whether the correction of hearing loss through the use of hearing aids can decrease the rate of cognitive decline or reduce dementia risk.

Our trial aims to investigate whether the correction of hearing loss through the use of hearing aids (HAs) could decrease the 12-month rate of cognitive decline among older adults at risk of dementia.

Methods

Aims

This trial will determine whether the correction of hearing loss through the use of hearing aids (HA) decreases the 12-month rate of cognitive decline among older adults at risk of dementia.

We will also investigate whether the correction of hearing loss has a beneficial impact on memory and executive functions, anxiety and depressive symptoms, quality of life, physical health, and health-related costs over 12 months.

We will explore whether the expected clinical gains achieved through the correction of hearing loss by 12 months can be sustained over an additional period of 12 months and if losses experienced through the non-correction of hearing loss can be reversed with the fitting of HAs after 12 months (i.e., HAs fitting for controls at 12 months with follow up of 12 months).

Study design

Two-arm parallel randomised controlled trial.

Participants and setting

We will recruit 180 older adults with mild cognitive impairment and hearing loss. The trial will be conducted at the Ear Science Institute Australia (ESIA) based in the Perth and Bunbury metropolitan regions, Western Australia as well as the Western Australian Centre for Health & Ageing, Perth, Australia. Participants will be recruited from the ESIA hearing clinics, aged-care homes, and hospital memory clinics. In addition, we will place advertisements in the local media and primary care networks, inviting interested participants for screening. If the recruitment of participants is lower than predicted, we will use the electoral roll list to select a random list of people aged ≥70 years living the study areas: they will receive information about the study and an invitation to contact the research office for screening if they believe they may be potentially eligible (the mail out will be de-identified – i.e., investigators will not have access to the list). This approach has been used successfully in other studies.

Eligibility criteria

Participants will:

Be older adults aged 70 years or older (cognitive decline is more pronounced later in life).

Have a Montreal Cognitive Assessment for the Hearing Impaired (HI-MOCA [11] greater than 18 and less than 26 (mild impairment).

Have better ear average hearing loss at 0.5, 1 & 2 kHz (3FAHL) > 23 dB or high-frequency average hearing loss (2, 3 & 4 kHz) (HFAHL) ≥ 40 dB as measured using air conduction pure-tone audiometry (HA fitting criteria recommended by Hearing Services Program in Australia for older adults with ARHL [12].

Be fluent English speakers.

Exclusion criteria

We will exclude participants who:

Have impaired instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) [13] due to cognitive deficits (requires assistance or is dependent in the use of telephone, shopping, housekeeping, laundry, transport, management of medications and finances) – i.e. have dementia [14] or major neurocognitive disorder.

Meet clinical criteria for cochlear implantation (unaided bilateral sensorineural hearing loss > 70 dBHL, and open-set sentence scores in quiet in the worse ear < 65% and in the better ear < 85% or open set phoneme scores in quiet in the worse ear < 45% and in the better ear < 65% with optimised HA fitting [15].

Have visual impairment that limits participant’s ability to read Times New Roman font size 16 (a requirement for two sentences of HI-MOCA).

Have a severe medical illness that limits the ability of the participant to attend appointments or sustain participation in the study for 24 months.

Plan to move away from the study area during the subsequent 24 months.

Are unable or unwilling to provide written, informed consent to participate.

Are unable to complete the motor screening task (MOT) module of the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB) due to visual impairment, inability to comprehend test instructions or inability to attend to the task due to dexterity problems [16].

Intervention

The intervention consists of three parts: (i) hearing assessment and HA discussion, (ii) HA fitting, verification and validation and (iii) HA review following daily use of HAs.

The intervention will be carried out by a qualified audiologist according to the Australian Audiological Society Standards in a standardised soundproof booth. All participants will be given a pair of Oticon OPN 1S hearing aids.

Outcomes

We will use several well-validated scales to assess our primary and secondary outcomes.

Primary outcome measures

Global cognitive abilities: Due to hearing impairment, older people may experience difficulty in following verbal instructions or completing tasks that heavily rely on hearing during cognitive assessments. This may result in overestimation of cognitive impairment in such individuals [5]. Hence, we have used a non-verbal global cognitive measure that has been validated to use with the hearing impaired older adults. The global cognitive abilities will be measured using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for the Hearing Impaired (HI- MoCA [11]. No significant difference was observed for MOCA and HI-MOCA scores in cognitively intact normal hearing participants, and the test-retest reliability coefficient was 0.66 [11].

Secondary outcome measures

Nonverbal cognition assessment using Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB) [16]- This assessment does NOT rely on verbal communication:

Attention Switching task (AST): is a test of executive functioning and provides a measure of cued attentional set-shifting [16]. AST is based on the Stroop test and relies heavily on the functions of the anterior right hemisphere and medial frontal structures.

Delayed Matching Sample (DMS): assesses participants’ ability to recognise complex visual patterns at different time intervals [16]. It is primarily sensitive to medial temporal lobe dysfunction.

Paired Associates Learning (PAL): PAL is a recall test of memory which assesses episodic visuospatial memory, learning and association ability [16]. PAL is primarily sensitive to the changes in medial temporal lobe functioning.

Spatial Working Memory (SWM): measures the retention and manipulation of visuospatial information in areas such as non-verbal working memory, working visuospatial memory and strategy use [16].

Other measures including safety measures

General physical & mental health

Participants will be asked to complete the following widely used and validated assessments:

Cognitive reserve questionnaire to obtain information on participant age, gender, education, work history and leisure activities [17].

Health status and Quality of life: Short Form survey (SF-12) [18].

Physical function: Functional Comorbidity Index (FCI) [19].

Depressive symptoms: Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [20].

Anxiety symptoms: Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI) [21].

Function: Lawton & Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) [22].

Social Support and interaction: de Jong Gierveld social support questionnaire [23].

Frailty: handgrip strength will be measured using a Jamar Analogue Hand Dynamometer [24].

Psychological and social adjustment problems resulting from hearing loss: Hearing Handicap Inventory of the Elderly (HHIE) [25].

Effectiveness of the HAs application: International Outcome Inventory for HAs (IOI-HA) [26].

Demographic questionnaire

Health-care utilisation cost questionnaire.

Hearing Assessment

The assessment of hearing will consist of two parts:

Peripheral hearing assessment will be based on tympanometry, which provides information about middle ear pathologies; pure-tone audiometry, which generates information on hearing thresholds across .25–.8 kHz frequency range; and speech perception in a quiet environment: Consonant-Nucleus-Consonant (CNC) word [27] and City University of New York (CUNY) sentence test [28].

Central hearing assessment will comprise of the following tests: Dichotic Digits Test (DDT) [29], Synthetic Sentence Identification with Ipsilateral Competing Message (SSI-ICM) [30] and Quick Speech in Noise (Quick-SIN) [31].

Procedures for the collection of study measures

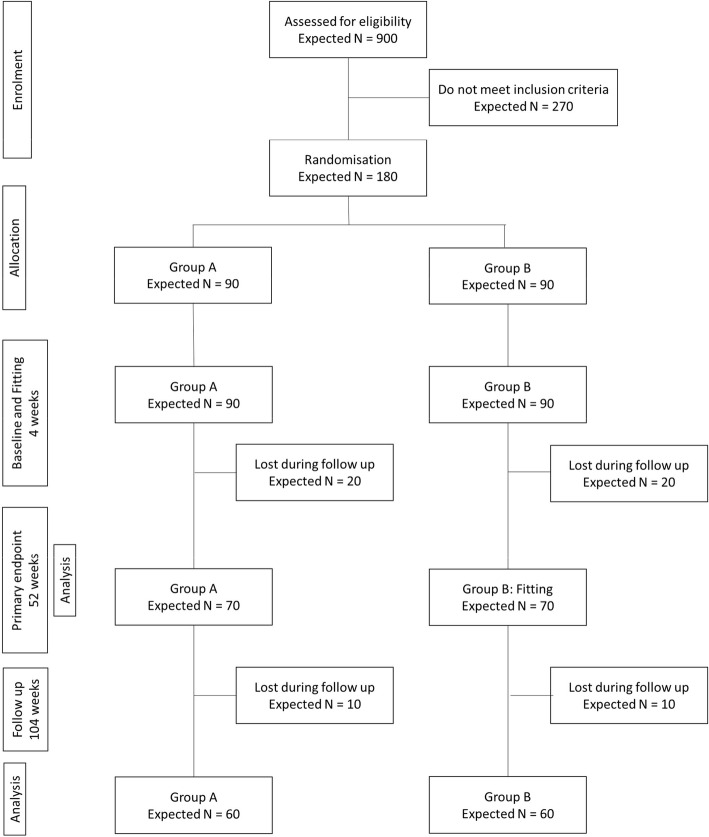

The procedure for the data collection will follow the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. During the screening process, participants who meet the criteria for inclusion in the study will be randomly assigned to either the experimental (A) or control (B) group. Group A participants will receive the intervention immediately after the baseline assessment, whereas group B participants will receive the intervention 12 months later (Fig. 1). All participants will be informed that if they get randomly allocated to group B, they will have to wait 12 months to receive the treatment. Those who prefer to receive HAs immediately without having to wait 12 months will be given the option to opt-out from the study. Cognition, mental health and QoL assessments will be carried out separately to the hearing assessments and HA fitting.

Fig. 1.

Anticipated participant recruitment flowchart

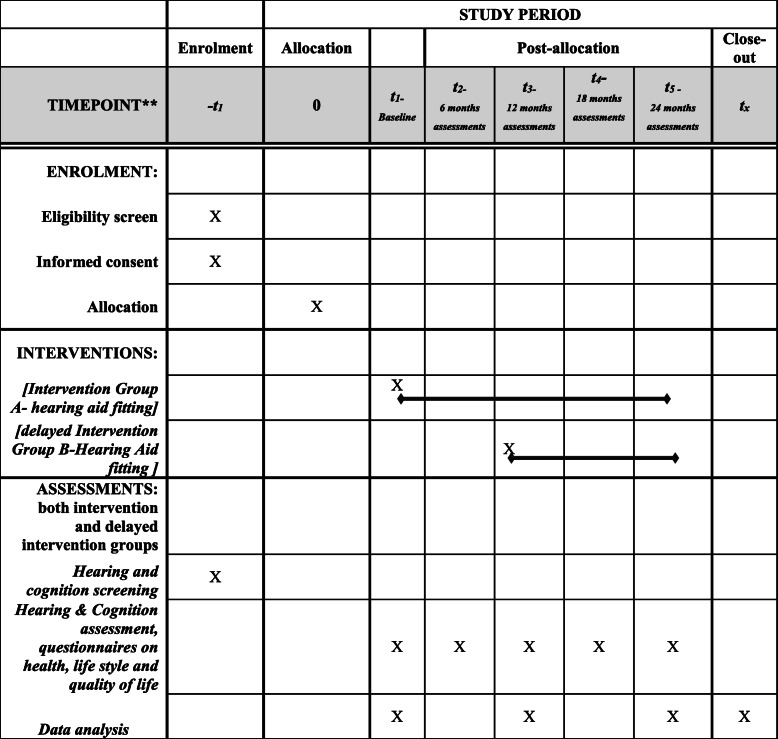

Group A will complete hearing assessment, cognitive, mental health and QoL assessment at the baseline, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months.

Group B will complete hearing assessment, cognitive, mental health and QoL assessment at the baseline, 6, 12 months, 18 and 24 months. (Primary endpoint analysis at 12 months and follow-up analysis at 24 months are shown in Fig. 1). Timeline of the study is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Timeline of the study

Intervention: will be conducted by a qualified Audiologist.

Part I: Hearing assessment and HA discussion

During this appointment, the participant will complete (1) a comprehensive case history on their medical and hearing history, (2) a Client Oriented Scale of Improvement (COSI) goals [32] for everyday listening situations and (3) a standard hearing assessment. An explanation on what are hearing aids and how they work, what they are used for, how to use them, and related questions and answers will be provided.

Part II: HA fitting, real-ear verification and validation -immediately following appointment part I.

The audiologist will program the HA and carry out the real-ear verification using real-ear insertion gain (REIG) to ensure that appropriate amplification is provided validation tasks will be carried out to determine that the participant is benefitting from the HAs [33]. Adjustments will be made to the devices so that the participant is comfortable with the devices.

Part III: HA review: 2 weeks after the HA fitting.

HA data logging information recorded in the software of the HA is analysed to ensure that the HA program provides the best solutions to the listening demands of the participant. Based on COSI goals, data logging information and feedback received from the participants, changes are made to the HA program.

HA review appointments at 12 and 24 months after HA fitting

These appointments are similar to Part II and III of the HA fitting appointments. During these appointments, a standard pure-tone audiometric assessment to obtain hearing thresholds, reprogramming of the HA according to the current hearing loss.

Measuring adherence with treatment

The Oticon Opn 1S HAs have a “log in“feature that records both the average number of hours and different listening environments in which the participant has used the HA. These data can be retrieved when the HA is connected to the program software, which will be done at all assessments. In addition, the participant will be asked to maintain a daily listening diary in which s/he records the number of hours the HA is worn.

Pilot test and sample size

In preparation of this trial, we conducted a pilot observational intervention study of two groups of hearing-impaired older adults: Group 1 [n = 35, mean age = 70.2 + 6.7 years, better ear four frequency average .5, 1, 2 & 4 kHz (BE 4PTA) = 31.92 dB, better ear high frequency average of 6 & 8 kHz (BE HF2PA) = 54.07 dB] and Group 2 [n = 13, mean age = 71.8 + 7.4 years, BE 4PTA = 33.46 dB, BE 2HFPTA = 55.57 dB]. A control group of 19 normal-hearing participants was also included. All participants completed hearing and a non-verbal cognitive assessment using the CANTAB test battery at baseline, 6 and 12 months. Hearing aids (HA) were fitted to Group 2 participants after the baseline assessment. Analysis of variance revealed that Group 2 participants (HA users) performed significantly better than Group 1 (non-HA users) on the delayed matching-to-sample (DMS) test of the CANTAB battery (p = .02, d = 0.38). We used G*Power software [34] to determine the required sample size for the study. Based on these pilot data, we calculated that a total of 140 participants would be required (70 in each group) to detect a conservative effect size of the intervention of d = 0.27 with two-sided α set at .05 and power of .90. To account for 25% of attrition over time, we estimated that a total of 180 participants would need to be recruited.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

The computer-generated randomisation sequence will be stratified by the severity of the hearing loss (mild to moderate vs severe) based on the results of the hearing assessment. Each stratification block will be associated with a random sequence of numbers assigned to the intervention and control group in random permuted blocks of 6, 8 or 10. This sequence will be stored in a password-protected server housed at the University of Western Australia and will be managed by a biostatistician not involved in this project. Once a participant consents and is enrolled, s/he will be automatically ascribed a number and group membership (intervention or control).

Due to the nature of the intervention, participants will know their group assignment, but research staff involved in the assessment of cognitive function, quality of life, mood and physical function will remain blind to treatment allocation. This will be achieved by directing participants to NOT: (i) discuss any aspects of the intervention during the assessments, (ii) wear their HAs during the assessment. Binaural hearing amplifiers will be used to facilitate the communication between participants and research staff during all assessment visits (including the 12 and 24-month visits).

Health economic analysis

This will involve the development of a model to estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared to the control. The analyses will be from the perspective of the health service and will be expressed as Quality-Adjusted Life Years gained. A particular focus of the economic evaluation will be a full assessment of the cost of delivering the intervention compared to that of the control group (including the costs of intervention material, costs of procedures, visits to health service provides and list of all medications). Given the feasibility of obtaining health administrative data within the study time frame, we will use a validated patient cost questionnaire to obtain self-reported health care utilisation data [35]. Whilst we recognise the potential for recall bias, there is evidence to suggest that this is a valid method of collecting data on health-care resource utilisation for use in economic evaluations, especially when administrative data is not easily available [36]. Costings information will be applied based on established economic costing methodologies drawing on primary research and secondary national tariffs [37]. Further, an application will be made to the Department of Health Linked data systems obtain pharmaceutical-based costs, Medicare-based costs and other associated costs including Mental Health Information System, Home and Community Care, Emergency Department Data, Aged Care Assessment and St John Ambulance related to each participant of the study.

The second aspect will include the assessment of the effectiveness of the intervention – effectiveness of the intervention and control will be measured using the SF-12, which is widely used in economic evaluations.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios will be calculated in terms of the incremental cost per sustained remission and the incremental cost per Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY) gained by the intervention. The QALY is a widely-used approach for estimating the quality of life benefits in economic evaluations. The values obtained from the SF-12 will be transformed into utility weights using the Short Form 6D algorithm [38] to formulate the cost per QALY. Sensitivity analysis will be undertaken to test the robustness of results.

Statistical analysis

All analyses will follow CONSORT guidelines. We will use standard descriptive statistics to compare basic sociodemographic and clinical data across treatment arms. We will use multilevel mixed models to investigate changes in cognitive and other scale scores over time. Mixed models provide estimates that are “intention-to-treat’ and allow for the investigation of interactions between group and time effects, as well as for the adjustment of possible imbalances between the groups following the randomisation. We will use imputed chain equations if the loss to follow up exceeds 25%. All probability tests will be two-tailed.

Discussion

The current paper discusses the methodology for a randomised control trial that investigates whether hearing loss intervention using hearing aids could delay or arrest the cognitive decline in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. One of the strengths of this trial is that it follows CONSORT guidelines for the design of randomised controlled trials. The recruitment of participants with mild cognitive deficits was guided by our desire to test a population at risk of dementia (when prevention may be possible) and by the difficulties associated with the consenting of older adults with moderate to severe cognitive impairment. Besides, those with severe to profound hearing loss who meet the criteria for a cochlear implant will not benefit from HA amplification, hence, including them would potentially undermine the impact of HA amplification on cognitive functions, mental health and QoL. We acknowledge, however, that our study will focus on the cognitive decline rather than conversion to dementia. At this stage, this is a “proof of concept’ investigation, as a dementia prevention trial would require a substantially larger sample and follow up. The projected outcomes of the current study can immediately be translated to practice through audiology clinics and will be applicable across practices around the world. Findings can also be used to inform audiologists, general practitioners and other health-care providers. This will provide important information for older people about the use of hearing aids to prevent worsening cognitive impairment. In addition, consumer support will be requested in disseminating lay summaries/information to the community. If cognitive decline can be delayed or arrested, this would improve the quality of life of older adults who are at risk of developing dementia. It may also lower costs to the health-care and social support systems, by decreasing the needs for services and residential care placement. It would also significantly reduce the overall burden borne by the community.

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to acknowledge the contribution from Ear Science Institute Australia Lions Hearing Clinics and members of the Audiology reference group for their input and support.

Abbreviations

- ARHL

Age-related hearing loss

- HA

Hearing aids

- ESIA

Ear Science Institute Australia

- HI-MOCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment for the Hearing Impaired

- 3FAHL

Three Frequency Average Hearing Loss

- HFAHL

High Frequency Average Hearing Loss

- IADL

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- dBHL

Decibel Hearing Loss

- MOT

Motor Screening Task

- CANTAB

Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Battery

- AST

Attention Switching task

- DMS

Delayed Matching Sample

- PAL

Paired Associates Learning

- SWM

Spatial Working Memory

- SF-12

Health status and Quality of life: Short Form Survey

- FCI

Functional Comorbidity Index

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire

- GAI

Geriatric Anxiety Inventory

- HHIE

Hearing Handicap Inventory of the Elderly

- IOI-HA

International Outcome Inventory for HAs

- CNC

Consonant-Nucleus-Consonant

- CUNY

City University of New York

- DDT

Dichotic Digits Test

- SSI-ICM

Synthetic Sentence Identification with Ipsilateral Competing Message

- Quick-SIN

Quick Speech in Noise

- QoL

Quality of Life

- COSI

Client Oriented Scale of Improvement

- REIG

Real Ear Insertion Gain

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- QALY

Quality Adjusted Life Year

Authors’ contributions

DJ, OA, AF, LF, PF and NL provided input into concept of the project, preparation of grant application and ethics approval documents. SR and MM provided input to the health economic analysis protocols of the project. MA, LC and AL provided input into hearing aid protocols of the study. All authors have reviewed and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received funding from Ron and Peggy Bell Legacy Trust, WA Department of Health Research Translation Project Grant and Rebecca L Cooper Foundation. The Oticon A/S, Denmark, provided hearing aids for the study. None of the funding bodies has provided any intellectual input into the design of the study and will not provide any input into data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This trial is registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR: 12618001278224). The ethics approval for the study was received from the University of Western Australia Human Ethics Committee (RA/4/20/4641). Written informed structured consent will be required from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation . Deafness and hearing loss. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Tweed TS, Klein BEK, Klein R, Mares-Perlman JA, et al. Prevalence of hearing loss in older adults in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;148(9):879. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009713. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jayakody DMP, Almeida OP, Speelman CP, Bennett RJ, Moyle TC, Yiannos JM, et al. Association between speech and high-frequency hearing loss and depression, anxiety and stress in older adults. Maturitas. 2018;110:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Seripa D, Imbimbo BP, Capozzo R, Quaranta N, et al. Age-related hearing impairment and frailty in Alzheimer’s disease: interconnected associations and mechanisms. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:113. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jayakody DMP, Friedland PL, Eikelboom RH, Martins RN, Sohrabi HR. A novel study on the association between untreated hearing loss and cognitive functions of older adults: baseline non-verbal cognitive assessment results. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017;43(1):182–191. doi: 10.1111/coa.12937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin FR, Metter EJ, O’Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2):214–220. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(3):332-84. 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The LANCET. 2020;396(10248):413-46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Vickland V, Chilko N, Draper B, Low LF, O’Connor D, Brodaty H. Individualised guidelines for the management of aggression in dementia - part 1: key concepts. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(7):1112–1124. doi: 10.1017/s1041610212000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford AH, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L, Almeida OP. Hearing loss and the risk of dementia in later life. Maturitas. 2018;112:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin VYW, Chung J, Callahan BL, Smith L, Gritters N, Chen JM, et al. Development of cognitive screening test for the severely hearing impaired: hearing-impaired MoCA. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(S1):S4–S11. doi: 10.1002/lary.26590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office of Hearing Services . Minimum Hearing Loss Threshold. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graf C. The Lawton instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scale. Medsurg Nurs. 2008;17(5):343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organisation . The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic criteria for research. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health Western Australia . Clinical Guidelines for Adult Cochlear Implant. Perth: Health Networks Branch, Department of Health; 2011. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cambridge Cognition . CANTAB eclipse test administration guide. Cambridge: UK Cambridge Cognition; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nucci M, Mapelli D, Mondini S. Cognitive reserve index questionnaire (CRIq): a new instrument for measuring cognitive reserve. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24(3):218–226. doi: 10.3275/7800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware EJ, Kosinski DM, Keller DS. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groll DL, To T. Bombardier C, Wright JG. The development of a comorbidity index with physical function as the outcome. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(6):595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pachana NA, Byrne GJ, Siddle H, Koloski N, Harley E, Arnold E. Development and validation of the geriatric anxiety inventory. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(1):103–114. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206003504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9(3 Part 1):179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur J Ageing. 2010;7(2). 10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Massy-Westropp NM, Gill TK, Taylor AW, Bohannon RW, Hill CL. Hand grip strength: age and gender stratified normative data in a population-based study. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:127. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ventry IM, Weinstein BE. The hearing handicap inventory for the elderly: a new tool. Ear Hear. 1982;3(3):128–134. doi: 10.1097/00003446-198205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox RM, Alexander GC. The international outcome inventory for hearing aids (IOI-HA): psychometric properties of the English version. Int J Audiol. 2002;41(1):30–35. doi: 10.3109/14992020209101309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson GE, Lehiste I. Revised CNC lists for auditory tests. J Speech Hear Disord. 1962;27:62–70. doi: 10.1044/jshd.2701.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boothroyd A, Hanin L, Hnath T. A sentence test of speech perception: reliability, set equivalence, and short term learning. New York: City University of New York; 1985. [Google Scholar] https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=A+sentence+test+of+speech+perception:+reliability,+set+equivalence,and+short+term+learning&author=A+Boothroyd&author=L+Hanin&author=T+Hnath&publication_year=1985&.

- 29.Musiek FE, Gollegly KM, Kibbe KS, Verkest-Lenz SB. Proposed screening test for central auditory disorders: follow up on the dichotic digits test test. Otol Neurotol. 1991;12(2):109–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orchik DJ, Burgess J. Synthetic sentence identification as a function of the age of the listener. Ear Hear. 1977;3(1):42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Killion MC, Niquette PA, Gudmundsen GI, Revit LJ, Banerjee S. Development of a quick speech-in-noise test for measuring signal-to-noise ratio loss in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;16(4):2395–2405. doi: 10.1121/1.1784440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dillon H, James A, Ginis J. Client oriented scale of improvement (COSI) and its relationship to several other measures of benefit and satisfaction provided by hearing aids. J Am Acad Audiol. 1997;8:27–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dillon H. Hearing aids. Sydney: Boomerang Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. doi: 10.3758/BF03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Brink M, van den Hout WB, Stiggelbout AM, Putter H, van de Velde CJH, Kievit J. Self-reports of health-care utilisation: diary or questionnaire? Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2005;21(3):298–304. doi: 10.1017/S0266462305050397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leggett EL, Khadaroo GR, Holroyd-Leduc LJ, Lorenzetti LD, Hanson LH, Wagg LA, et al. Measuring Resource Utilisation: A Systematic Review of Validated Self-Reported Questionnaires. Medicine. 2016;95(10):e2759-e. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care Programmes. 4. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brazier EJ, Roberts EJ. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care. 2004;42(9):851–859. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135827.18610.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.