Abstract

Background

The Researching cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes (REWIND) double blind randomized trial demonstrated that weekly subcutaneous dulaglutide 1.5 mg, a glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonist, versus matched placebo reduced the first outcome of major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction or nonfatal stroke (594 versus 663 events) in 9901 persons with type 2 diabetes and either chronic cardiovascular disease or risk factors, and followed during 5.4 years. These findings were based on a time-to-first-event analysis and preclude relevant information on the burden of total major events occurring during the trial. This analysis reports on the total cardiovascular or fatal events in the REWIND participants

Methods

We compared the total incidence of MACE or non-cardiovascular deaths, and the total incidence of expanded MACE (MACE, unstable angina, heart failure or revascularization) or non-cardiovascular deaths between participants randomized to dulaglutide and those randomized to placebo. Incidences were expressed as number per 1000 person-years. Hazard ratios (HR) were calculated using the conditional time gap and proportional means models.

Results

Participants had a mean age of 66.2 years, 46.3% were women and 31% had previous cardiovascular disease. During the trial there were 1972 MACE or non-cardiovascular deaths and 3673 expanded MACE or non-cardiovascular deaths. The incidence of total MACE or non-cardiovascular deaths in the dulaglutide and placebo groups was 35.8 and 40.3 per 1000 person-years, respectively [absolute reduction = 4.5 per 1000 person-years; conditional time gap HR 0.90 (95% CI, 0.82–0.98) p = 0.020, and proportional means HR 0.89 (95% CI, 0.80–0.98) p = 0.022]. The incidence of total expanded MACE or non-cardiovascular deaths in the dulaglutide and placebo groups was 67.1 and 74.7 per 1000 person-years, respectively [absolute reduction = 7.6 per 1000 person-years; conditional time gap HR 0.93 (95% CI, 0.87–0.99) p = 0.023, and proportional means HR 0.90 (95% CI, 0.82–0.99) p = 0.028].

Conclusions

These findings suggest that weekly subcutaneous dulaglutide reduced total cardiovascular or fatal event burden in people with type 2 diabetes at moderate cardiovascular risk.

Clinical Trial Registration: https://www.clinicaltrials.gouv. Unique Identifier NCT01394952).

Keys words: Type 2 diabetes, Cardiovascular disease, Glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonists

Background

People with diabetes continue to be at high risk for cardiovascular (CV) events and premature death despite the use of established cardioprotective therapies. Large randomized placebo-controlled CV outcomes trials have therefore been conducted to assess the effects of glucose-lowering drugs on the hazard of major adverse CV events (MACE) defined as nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke or death from CV causes. Seven such trials using glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) have now been published. Four of them reported a reduced hazard of MACE [1–4], and a meta-analysis of these plus three additional trials whose results were neutral [5–7], reported a statistically significant hazard ratio of 0.88 for this outcome [8]. One of these trials was the Researching cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes (REWIND) trial, in which the addition of a once-weekly subcutaneous injection of dulaglutide (1.5 mg) significantly reduced the hazard of MACE by 12% in 9901 individuals with type 2 diabetes with either chronic CV disease or CV risk factors [4]. It also clearly demonstrated similar effect sizes in the subgroups with (31.5% of participants) and without (68.5% of participants) known CV disease.

These 7 CV outcomes trials all reported time-to-occurrence of the first MACE. Limiting the analysis to time-to-the first event precludes relevant clinical information pertaining to the total event burden experienced by participants [9–16]. To assess the impact of dulaglutide on total major events in the REWIND trial, we compared the composite of total number of MACE or non-CV deaths and the composite of total number of expanded MACE (MACE, heart failure, unstable angina or revascularization) or non-CV deaths between participants randomized to the GLP-1 RA and those randomized to placebo.

Methods

Trial design and study population

The trial design, population recruitment, baseline characteristics and results have been reported [4, 17, 18]. In brief, REWIND was a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial done at 371 sites in 24 countries. Eligibility criteria included age 50 years and older with established or newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, a HbA1c ≤ 9.5% on stable doses of up to 2 oral glucose-lowering drugs, and a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 23 kg/m2. In addition, people ≥ age 50 had to have CV disease (previous MI, ischemic stroke, revascularization, hospitalization for unstable angina or imaging evidence of myocardial ischemia), those ≥ age 55 had to have myocardial ischemia or coronary, carotid or lower limb arterial stenosis greater than 50%, left ventricular hypertrophy, albuminuria or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min per 1.73 m2, and those ≥ age 60 without evidence of CV or renal disease needed to have at least 2 of the following risk factors: hypertension, dyslipidemia, tobacco consumption or abdominal obesity. The main exclusion criteria were: cancer within the previous 5 years, eGFR < 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2, severe hypoglycemia in the previous year, liver disease, life expectancy less than 1 year, a CV event within the previous 2 months, or plans for revascularisation. The REWIND protocol was approved by Ethics Committees at all participating sites and all participants provided written informed consent.

Random assignment and follow-up

REWIND participants were recruited between August 18, 2011 and August 14, 2013. After a 3-week run-in period, eligible participants were randomized to either a weekly subcutaneous injection of dulaglutide 1.5 mg or matched placebo. Follow-up visits were every 3 to 6 months to document any CV disease or other health problems and to give lifestyle guidance. Among the participants randomized to dulaglutide 82.2% took the study medication from randomization until either a primary outcome or final follow-up compared with 83.1% of those randomized to placebo. All hospitalizations were recorded. REWIND was an event-driven trial with a target of at least 1200 confirmed first occurrences of a MACE consisting of CV death, nonfatal MI or nonfatal stroke. The trial was terminated on August 21, 2018 at which point, 1257 people had experienced a confirmed first MACE.

Events

The analyses for this report focus on the composite of total number of pre-specified MACE or non-CV deaths, and the composite of total number of expanded MACE outcomes (MACE, heart failure requiring hospitalization or urgent medical visit for treatment, unstable angina requiring hospitalization for treatment, or coronary, carotid or peripheral revascularization) or non-CV deaths from any cause. Various combinations of CV or fatal events were also analyzed. All of the events reported here were adjudicated by an independent committee of physicians blinded to the study medication and used pre-specified definitions [4].

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were summarized by counts and proportions, and continuous variables by means and standard deviations (SD). Trends in proportions were assessed using the Cochrane-Armitage trend test, and trends in means were assessed using simple linear regression. Analyses were performed separately for each composite event and focused on the total number of events during follow-up, and not the number of people with one or more events. Therefore, an individual who experienced a heart failure event, followed by a MACE, and later on by death from pneumonia would be counted as having had 3 events.

Incidence rates of events were estimated as the number of events per 1000 person-years (py) of follow-up. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for total MACE or non-CV deaths and total expanded MACE or non-CV deaths were estimated using both the conditional gap time model [19] and the proportional means model [20]. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the HR and 95% CI of first outcomes. All analyses were done using SAS (version 9.4).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The REWIND trial randomly assigned 9901 people, including 4589 (46.3%) women and 5312 (53.7%) men of mean (SD) age 66.2 (6.5) years to the addition of weekly subcutaneous injections of either dulaglutide 1.5 mg or placebo. Detailed baseline characteristics according to randomized treatment group have already been published [4]. Baseline characteristics in people who did and did not experience one or more MACE or non-CV deaths during follow-up are presented in Table 1. Numbers of events experienced during follow-up were statistically correlated with age, male sex, white background, tobacco use, prior CV disease, heart failure, diabetes duration, systolic blood pressure, HbA1c, use of beta blockers, blood pressure drugs (other than renin-angiotensin system modulators), antiplatelet drugs, sulfonylureas and insulin, and were inversely related to eGFR, and metformin use.

Table 1.

Distribution of number MACE or non-CV deaths according to baseline characteristics

| Participants | Number of events per participant | P (trend) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | ≥ 2 | |||

| Randomized | 9901 | 8233 | 1425 | 243 | |

| Mean age (years) | 9901 | 65.8 (6.3) | 68.1 (7.3) | 67.9 (8.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Female | 4589 | 3972 (48.2) | 522 (36.6) | 95 (39.1) | < 0.0001 |

| White | 7498 | 6207 (75.4) | 1096 (76.9) | 195 (80.3) | 0.044 |

| Tobacco consumption | 1407 | 1113 (13.5) | 254 (17.8) | 40 (16.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Prior cardiovascular disease | 3114 | 2362 (28.7) | 614 (43.1) | 138 (56.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 9224 | 7658 (93.0) | 1338 (93.9) | 228 (93.8) | 0.23 |

| Prior heart failure | 853 | 626 (7.6) | 184 (12.9) | 43 (17.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Mean diabetes duration (years) | 9901 | 10.3 (7.04) | 11.4 (7.91) | 11.8 (8.67) | < 0.0001 |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 9900 | 32.4 (5.7) | 32.0 (5.78) | 32.6 (6.12) | 0.16 |

| Mean SBP (mm Hg) | 9901 | 137 (16.5) | 140 (18.0) | 139 (17.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Mean DBP (mm Hg) | 9901 | 78.5 (9.7) | 78.6 (10.3) | 77.2 (10.6) | 0.463 |

| Mean HbA1c | 9876 | 7.3 (1.0) | 7.4 (1.1) | 7.4 (1.0) | 0.0062 |

| Mean eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) | 9640 | 77.9 (22.3) | 71.7 (24.0) | 70.7 (23.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Mean LDL (mmol/L) | 9590 | 2.55 (0.97) | 2.64 (1.00) | 2.48 (0.96) | 0.092 |

| Medications | |||||

| Metformin | 8037 | 6737 (81.8) | 1111 (78.0) | 189 (77.8) | 0.0004 |

| Sulfonylurea | 4552 | 3740 (45.4) | 700 (49.1) | 112 (46.1) | 0.0430 |

| Insulin | 2363 | 1889 (22.9) | 409 (28.7) | 65 (26.8) | < 0.0001 |

| DPP4i | 564 | 484 (5.9) | 64 (4.5) | 16 (6.6) | 0.220 |

| Thiazolidinedione | 168 | 150 (1.8) | 14 (1.0) | 4 (1.7) | 0.073 |

| Other glucose lowering drugs | 32 | 28 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | 0 | 0.39 |

| ACEI/ARB | 8068 | 6700 (81.4) | 1166 (81.8) | 202 (83.1) | 0.47 |

| Beta blocker | 4512 | 3628 (44.1) | 737 (51.7) | 147 (60.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Other BP drug | 5599 | 4568 (55.5) | 871 (61.1) | 160 (65.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Statin | 6547 | 5450 (66.2) | 907 (63.7) | 190 (78.2) | 0.27 |

| Fibrate | 898 | 756 (9.2) | 119 (8.4) | 23 (9.5) | 0.52 |

| Antiplatelet | 5342 | 4365 (53.0) | 812 (57.0) | 165 (67.9) | < 0.0001 |

Data are shown as N (%) or Mean (SD); BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LDL, low density lipoprotein; DPP4i, dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitor; ACEI/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker

Events during follow-up

During a median follow-up period of 5.4 years (IQR 5.1–5.9), 1257 of the 9901 (12.7%) participants experienced at least one MACE, 1918 (19.4%) experienced at least one expanded MACE (Additional file 1: Table S1), and 465 (4.7%) died from non-CV causes.

By the end of follow-up there were a total of 932 MACE or non-CV deaths in dulaglutide group participants (35.8 per 1000 py) and 1040 such outcomes (40.3 per 1000 py) in placebo group participants (Table 2). The total number of MACE or non-CV deaths was, therefore, reduced by an absolute amount of 4.5 per 1000 py in the dulaglutide treatment group. This was reflected in a 10% reduced hazard using the conditional time gap model [HR 0.90 (95% CI, 0.82–0.98) p = 0.020] and an 11% reduced hazard using the proportional means model [HR 0.89 (95% CI, 080–0.98) p = 0.022]. Similar effects were noted within subgroups (Additional file 1: Table S2) defined by age, sex, prior CV disease, HbA1c levels, and use of statins, renin-angiotensin drugs or metformin (interaction P values all ≥ 0.15).

Table 2.

Incidences and hazard ratios of the composites of total CV events or non-CV deaths

| Composite event | Dulaglutide group | Placebo group | Events avoideda | Conditional time gap model | Proportional means model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (/1000py) | N (/1000py) | N (N/1000py) | HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| MACE or non-CV death | 932 (35.8) | 1040 (40.3) | 108 (4.5) | 0.90 (0.82–0.98) | 0.020 | 0.89 (0.80–0.98) | 0.022 |

| MACE, UA or non-CV death | 1034 (39.7) | 1123 (43.5) | 89 (3.8) | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) | 0.052 | 0.91 (0.83–1.01) | 0.066 |

| MACE, HF or non-CV death | 1195 (45.9) | 1372 (53.2) | 177 (7.3) | 0.91 (0.84–0.99) | 0.021 | 0.86 (0.78–0.96) | 0.006 |

| MACE, Revasc or non-CV death | 1399 (53.8) | 1519 (58.9) | 120 (5.1) | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 0.030 | 0.91 (0.83–1.01) | 0.0632 |

| MACE, UA, HF, Revasc or non-CV death | 1747 (67.1) | 1926 (74.7) | 179 (7.6) | 0.93 (0.87–0.99) | 0.023 | 0.90 (0.82–0.99) | 0.028 |

aDifference in numbers (and rate) of outcomes in the dulaglutide group versus the placebo group; N, number of outcomes; py, person-year; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; CV, cardiovascular; UA, unstable angina; HF, heart failure; Revasc, revascularization

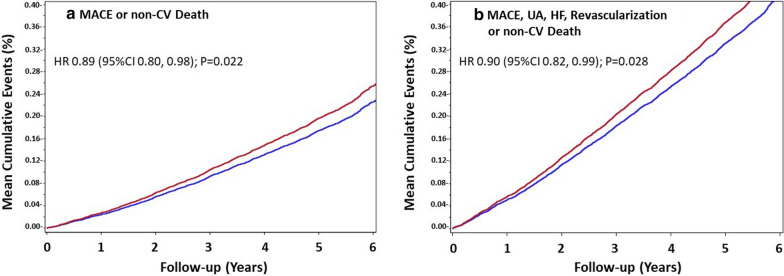

During the same period there were a total of 1747 expanded MACE or non-CV deaths in dulaglutide group participants (67.1 per 1000 py) and 1926 such outcomes (74.7 per 1000 py) in placebo group participants. The total number of MACE or non-CV deaths was, therefore, reduced by an absolute amount of 7.6 per 1000 py in the dulaglutide treatment group. This was reflected in a 7% reduced hazard using the conditional time gap model [HR 0.93(95% CI (0.87–0.99) p = 0.023] and a 10% reduced hazard using the proportional means model [HR 0.90 (95% CI 0.82–0.99) p = 0.028]. The mean cumulative event curves for both composite outcomes began to diverge after the first year and continued diverging until the completion of the study showing a lower rate of outcomes in participants randomized to dulaglutide than in those randomized to placebo (Fig. 1). Similar treatment group differences were noted for the composite of total MACE, unstable angina or death, total MACE, heart failure or death, and total MACE, revascularization or death (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence of the composite of total MACE or non-CV deaths (a) and the composite of total expanded MACE or non-CV deaths (b) in the dulaglutide group (blue line) and the placebo group (red line) during the follow-up. The hazard ratios (HR) are from the proportional means model

As noted in the Tables 3 and Additional file 1: Table S3, there were 1668 first MACE or non-CV deaths, comprising 789 in the dulaglutide group and 879 in the placebo group, [HR 0.88 (95% CI, 0.80–0.97) p = 0.011]. A similar pattern was seen for the 2286 first expanded MACE or non-CV deaths, that included 1097 in the dulaglutide group and 1189 in the placebo group, [HR 0.91 (95% CI, 0.84–0.99) p = 0.024].

Table 3.

Estimated effects of dulaglutide on the first composite outcome

| Composite event | Dulaglutide group | Placebo group | People spareda | Cox model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (N/1000py) | N (N/1000py) | N (N/1000py) | HR (95% CI) | p | |

| MACE or non-CV death | 789 (31.2) | 879 (35.3) | 90 (4.1) | 0.88 (0.80, 0.97) | 0.011 |

| MACE, UA, or non-CV death | 859 (34.3) | 933 (37.8) | 74 (3.5) | 0.91 (0.83, 0.99) | 0.041 |

| MACE, HF or non-CV death | 880 (35.3) | 983 (40.1) | 103 (4.8) | 0.88 (0.80, 0.96) | 0.0054 |

| MACE, Revasc, or non-CV death | 1002 (40.8) | 1090 (44.9) | 88 (4.1) | 0.91 (0.83, 0.99) | 0.028 |

| MACE, UA, HF, Revasc, or non-CV death | 1097 (45.3) | 1189 (49.8) | 92 (4.5) | 0.91 (0.84, 0.99) | 0.024 |

aDifference in numbers (and rate) of people experiencing a first composite event in the dulaglutide group versus the placebo group; CV, cardiovascular; py, person-year; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; UA, unstable angina; HF, heart failure; Revasc, revascularization

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of data from the REWIND trial, participants randomized to a once-weekly subcutaneous injection of dulaglutide 1.5 mg had a reduced total number of CV or fatal outcomes in addition to the number of first CV or fatal events compared with participants randomized to placebo. Moreover, the reduction in absolute numbers of events was greater for expanded MACE or non-CV deaths than for MACE or non-CV deaths in the dulaglutide treatment group.

The pre-specified primary analyses of all CV outcomes trials with GLP-1 receptor agonists, including REWIND, focused on estimating a participant’s risk of experiencing the first primary CV outcome, MACE after randomization. The reported HRs therefore reflect differences in the time from randomization to the first outcome in people who were randomly assigned to the active versus control therapy. The previously reported HR of 0.88 for dulaglutide versus placebo in the REWIND trial means that on average at any time-point after randomization, people who had been randomly assigned to dulaglutide were 12% less likely to have experienced a first post-randomization MACE than people who had been randomized to placebo [4]. Although this provides important information regarding the therapeutic effect of dulaglutide, patients and health care providers are also interested in knowing the total burden of serious CV events, and deaths from any cause in participants treated with dulaglutide. The estimated HR of about 0.9 for the burden of total MACE or non-CV death therefore focuses on events and not participants. It means that at any time-point after randomization, there were 10% fewer events in people randomly assigned to dulaglutide versus placebo. In the participants with a placebo-group MACE or non-CV death rate of 40.3 per 1000 py, this 10% difference would be consistent with 108 fewer MACE or non-CV deaths, and 179 fewer expanded MACE or non-CV deaths (with a placebo rate of 74.7 per 1000 py) in the dulaglutide group during the 5.4-year follow-up. If the results of this post hoc analysis are replicated, we hypothesize that the number of events avoided would be higher in individuals with event rates higher than those reported in Table 2.

The inclusion of non-CV death within the primary analyses presented here represents a conservative approach to estimating the effect of dulaglutide on the overall burden of CV disease as well as on the time to the first occurrence. First, death from any cause is clearly relevant to both participants and providers. Second, including all-cause deaths versus just CV deaths eliminates any misclassification of the cause of death (i.e. CV or non-CV death). Finally, it eliminates the possibility that a benefit of the drug on event burden would be negated by an increase in death, also referred to as the competing risk of death [21]. Whereas some investigators addressed this possibility in sensitivity analyses [13–15], we and others have integrated all-cause death into the main analyses of event burden [16]. Notably, the estimated HR of 0.88 for the time to the occurrence of the first MACE outcome or non-CV death was identical to the previously reported HR for the first occurrence of MACE alone [4]. However, the addition of non-CV deaths increases the event rates in both treatment groups compared with MACE alone and hence the number of people spared from experiencing an event. This is reflected in the absolute risk reduction which was 3.1 per 1000 py for the first occurrence of a MACE as previously reported (594 versus 663 events) [4], and 4.1 per 1000 py for the first occurrence of a MACE or non-CV death as noted in Additional file 1: Table S3 (789 versus 879 events).

The finding of a reduced burden of CV events in the REWIND trial is similar to the results of an analysis of event burden from the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes Evaluation of cardiovascular Results (LEADER) trial of another GLP-1 RA. In this analysis liraglutide was associated with a reduction of total (first and recurrent) MACE by 16% and of total CV events by 13% in 9340 participants followed for a median of 3.8 years [15]. Notably, inclusion of non-CV deaths in a sensitivity analysis did not alter their findings. The higher outcome reduction rates in the LEADER trial than in the REWIND mostly result in a higher risk population; indeed, 83% of the LEADER enrolled participants had a chronic CV disease compared with 31% of the REWIND enrolled participants.

Although the exact mechanism of the benefit of dulaglutide or other GLP-1 receptor agonists on CV disease reduction is unknown, possibilities include a decrease of risk factors such as high HbA1c, LDL-cholesterol, blood pressure and bodyweight as well as potential effects on the atherothrombotic process by improving endothelial and platelet functions [22] and attenuating the arterial plaque progression by reducing inflammation and vascular tone [23]. The fact that other GLP-1 receptor agonists such as liraglutide and semaglutide have qualitatively similar effects on CV events, metabolic and other indices overall and within sub-groups is consistent with general “class effect” of these drugs [24–26].

Limitations

These analyses are limited by the fact that they were not pre-specified and causal conclusions should not be drawn. Strengths include the 5.4-year median follow-up period, the large number of participants from many countries with well characterized baseline clinical findings, the high proportion of enrolled women, and the inclusion of all deaths in the composite event as a measure of total event burden.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that dulaglutide reduced the event burden of CV or fatal outcomes in a population at moderate CV risk. The absolute reduction was greatest for the composite outcome that included an expanded definition of a MACE. Our study supports the clinical implication of assessing all CV events or deaths in addition to the first manifestation of the primary outcome of randomized trials to capture the impact of the pharmacological intervention on the burden of disease.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Number of Participants who Experienced Varying Numbers of CV Events. Table S2. Effect of dulaglutide on Total MACE or non-Cardiovascular Death in subgroups. Table S3. Number of Participants who Experienced Varying Numbers of CV Events or on non CV deaths.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants and the staff of the REWIND trial for their valuable contributions.

Abbreviations

- ACEI

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

- ARB

Angiotensin receptor blocker

- BMI

Body mass index

- BP

Blood pressure

- CI

Confidence interval

- CV

Cardiovascular

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- DPP4i

Dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 inhibitor

- eGFR

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- GLP-1

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- HbA1c

Glycated hemoglobin A1c

- HF

Heart failure

- HR

Hazard ratio

- LDL

Low density lipoprotein

- MACE

Major adverse cardiovascular event

- MI

Myocardial infarction

- py

Person-year

- Revasc

Revascularization

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- UA

Unstable angina

Authors’ contributions

GRD and HCG wrote first draft and LD did the statistical analysis. All authors were involved in the REWIND trial. They reviewed the data and provided comments on the different versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The REWIND trial and this post hoc analysis were funded by Eli Lilly.

Availability of data and materials

All the data for the present report came from the Population Health Institute (PHRI) in Hamilton, Canada. PHRI did also all data analysis for the REWIND trial. The REWIND main trial data are in references 4, 17 and 18. The REWIND data sharing policy is described in the Additional file 1.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics review boards responsible for each of the 371 participating sites (24 countries) approved the protocol and each of the 9901 participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

GRD received honoraria from BAYER for lectures. LR received research grants from Swedish Heart–Lung Foundation, Stockholm County council, Family Erling Perssons Foundation and Boehringer-Ingelheim and speaker honoraria from Bayer AG, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk. LAL received research grants from, provided CME on behalf of and/or acted as an adviser to AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, GSK, Janssen, Lexicon, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Servier. ML is employed by Eli Lilly. LD has no competing interests. JLP has no competing interests. CMA is employed by Eli Lilly. JES has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Mylan, Sanofi. Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Boehringer Ingelheim. IC has received honoraria for lectures and consulting fees from Abbot, Medtronic, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Novartis and MSD. WCCPLJ has received honoraria for speaking from Merck, Menarini, Sanofi, Abbott, WCC has received institutional grant support from Eli Lilly. FL has no competing interests. EGCM acted as an adviser for Servier and received honoraria from Menarini, Sanofi, MSD, Silanes, Novo, Stendhal, Boryun for lectures. VP has no competing interests. NP has no competing interests. JB received research grants from Eli Lilly, ReCor, and Ablative Solutions. He is a consultant for both Medtronic and Up-to-Date. WHHS provided CME and/or acted as an adviser to MSD, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Tanabe, Takeda, Eli Lilly, Bayer’s, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. TTK has no competing interests. PJR has no competing interests. MK has no competing interests. SH has no competing interests. PP has no competing interest. HMC has received grants from Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Regeneron, Pfizer, Novo Nordisk, honoraria for speaker bureau from Eli Lilly and advisory panel from Sanofi Aventis and Novartis, and is shareholder Roche Pharma. MCR reports grant support through Oregon Health & Science University from Astra Zeneca, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk, and honoraria for consulting from Adocia, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Intercept, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Theracos. HCG holds the McMaster-Sanofi Population Health Institute Chair in Diabetes Research and Care. He reports research grants from Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Merck, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi; honoraria for speaking from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; and consulting fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Janssen, Sanofi, and Kowa.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12933-020-01179-1.

References

- 1.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JFE, Nauck MA, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, Eliaschewitz FG, Jodar E, Leiter LA, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834–1844. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez AF, Green JB, Janmohamed S, D’Agostino RB, Granger CB, Jones NP, et al. Albiglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Harmony Outcomes): a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1519–1529. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32261-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmann M, Pais P, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):121–130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31149-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, Dickstein K, Gerstein HC, Kober LV, et al. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 Diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(23):2247–2257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holman RR, Bethel A, Mentz RJ, Thompson VP, Lokhnygina Y, Buse JB, et al. Effect of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13):1228–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husain M, Birkenfeld AL, Donsmark M, Dungan K, Eliaschewitz FG, Franco DR, et al. Oral semaglutideand cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(9):841–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristensen SL, Rorth R, Jhund PS, Docherty KF, Sattar N, Preiss D, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptors agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(10):776–785. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy SA, Antman EM, Wiviott SD, Weerakkody G, Morocutti G, Huber K, et al. Reduction in recurrent cardiovascular events with prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes from the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(20):2473–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murphy SA, Cannon CP, Wiviott SD, McCabe CH, Braunwald E. Reduction in recurrent cardiovascular events with intensive lipid-lowering statin therapy compared with moderate lipid-lowering statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes from the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(25):2358–2362. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tikkanen MJ, Szarek M, Fayyad R, Holme I, Cater NB, Faergema O, et al. Total cardiovascular disease burden: comparing intensive with moderate statin therapy insights from the IDEAL (Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(25):2353–2357. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LaRosa JC, Deedwania PC, Shepherd J, Wenger NK, Greten H, DeMicco DA, et al. Comparison of 80 versus 10 mg of atorvastatin on occurrence of cardiovascular events after the first event (from the Treating to New Targets [TNT] trial) Am J Cardiol. 2010;105(3):283–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohli P, Wallentin L, Reyes E, Horrow J, Husted S, Angiolillo DJ, et al. Reduction in first and recurrent cardiovascular events with ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel in the PLATO study. Circulation. 2013;127(6):673–680. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.124248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, Ketchum SB, et al. Effects of icosapent ethyl on total ischemic events : from REDUCE-IT. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(22):2791–2802. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verma S, Bain SC, Buse JB, Idorn T, Rasmussen S, Orsted DD, Nauck MA. Occurrence of first and recurrent major adverse cardiovascular events with liraglutide treatment among patients with type 2 diabetes and high risk of cardiovascular events : a post hoc analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4(12):1214–20. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szarek M, White HD, Schwartz GG, Alings M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, et al. Alirocumab reduces total nonfatal cardiovascular and fatal events. The Odyssey Outcomes trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(4):387–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmann M, Pais P, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of participants in the Researching cardiovascular Events with a Weekly INcretin in Diabetes (REWIND) trial on the cardiovascular effects of dulaglutide. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(1):42–49. doi: 10.1111/dom.13028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmann M, Pais P, et al. Dulaglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an exploratory analysis of the REWIND randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):131–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31150-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prentice RL, Williams BJ, Peterson AV. On the regression analysis of multivariable failure time data. Biometrika. 1981;68(2):373–379. doi: 10.1093/biomet/68.2.373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin DY, Wei LJ, Yang I, Ying Z. Semiparametric regression for the mean and rate functions of recurrent events. J Royal Stat Soc B. 2000;62(4):711–730. doi: 10.1111/1467-9868.00259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks; new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sposito AC, Berwanger O, de Carvalho LSF, Saraiva JFK. GLP-1RAs in type 2 diabetes: mechanisms that underline cardiovascular effects and overview of cardiovascular outcome data. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0800-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim S, Kim KM, Nauck MA. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and cardiovascular events: class effects versus individual patterns. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018;29(4):238–248. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leiter LA, Bain SC, Hramiak I, et al. Cardiovascular risk reduction with once-weekly semaglutide in subjects with type 2 diabetes: a post hoc analysis of gender, age, and baseline CV risk profile in the SUSTAIN 6 trial. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0871-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pratley RE, Aroda VR, Lingvay I, et al. Semaglutide versus dulaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes (SUSTAIN 7): a randomised, open-label, phase 3b trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(4):275–286. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yabe D, Nakamura J, Kaneto H, et al. Safety and efficacy of oral semaglutide versus dulaglutide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (PIONEER 10): an open-label, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3a trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:382–406. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Number of Participants who Experienced Varying Numbers of CV Events. Table S2. Effect of dulaglutide on Total MACE or non-Cardiovascular Death in subgroups. Table S3. Number of Participants who Experienced Varying Numbers of CV Events or on non CV deaths.

Data Availability Statement

All the data for the present report came from the Population Health Institute (PHRI) in Hamilton, Canada. PHRI did also all data analysis for the REWIND trial. The REWIND main trial data are in references 4, 17 and 18. The REWIND data sharing policy is described in the Additional file 1.