Abstract

Background:

Gastroesophageal adenocarcinomas (GEA) are heterogenous cancers where immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have robust efficacy in heavily inflamed microsatellite instability (MSI) or Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) positive subtypes. ICI responses are markedly lower in diffuse/genome-stable (GS) and chromosomal instable (CIN) GEAs. In contrast to EBV and MSI subtypes, the tumor microenvironment of CIN and GS GEAs have not been fully characterized to date, which limits our ability to improve immunotherapeutic strategies.

Patients and methods:

Here we aimed to identify tumor-immune cell association across GEA subclasses using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (N=453 GEAs) and archival GEA resection specimen (N=63). TCGA RNAseq data were used for computational inferences of immune cell subsets, which were correlated to tumor characteristic within and between subtypes. Archival tissues were used for more spatial immune characterization spanning immunohistochemistry and mRNA expression analyses.

Results:

Our results confirmed substantial heterogeneity in TME between distinct subtypes. While MSI-high and EBV+ GEAs harbored most intense T cell infiltrates, the GS group showed enrichment of CD4+T cells, macrophages and B cells and, in ~50% of cases, evidence for tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs). In contrast, CIN cancers possessed CD8+T cells predominantly at the invasive margin while tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) showed tumor infiltrating capacity. Relatively T cell-rich ‘hot’ CIN GEAs were often from Western patients, while immunological ‘cold’ CIN GEAs showed enrichment of MYC and cell cycle pathways, including amplification of CCNE1.

Conclusion:

These results reveal the diversity of immune phenotypes of GEA. Half of GS GCs have TLSs and are therefore promising candidates for immunotherapy. The majority of CIN GEAs, however, exhibit T cell exclusion and infiltrating macrophages. Associations of immune-poor CIN GEAs with MYC activity and CCNE1 amplification may enable new studies to determine precise mechanisms of immune evasion, ultimately inspiring new therapeutic modalities.

Keywords: immunotherapy, gastric cancer subtypes, chromosomal instability, tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS)

Introduction

Gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma (GEA) is a deadly disease in need for new therapies1. Among the most exciting developments in oncology are immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) such as inhibitors of programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)2 which has shown response rates of 11–16% in unselected GEA patients3,4.

Study of predictors of ICI efficacy in GEA has been enhanced by molecular classifications through The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)5,6. Epstein-Barr Virus positive (EBV+) and microsatellite instability (MSI) tumors have intense T cell infiltrates and high PD-L1 expression7 and respond best tot ICI8. The remaining two groups, chromosomal instability (CIN) and the genome stable subtype (largely gastric cancers with diffuse histology) showed less T cells7,9 and poor responses to ICI10.

Although we are only starting to understand response to ICI, these drugs require an endogenous adaptive immune response to be effective11. For MSI and EBV GEAs, T cells are presumably activated in response to a high mutational/neoantigen load and viral antigens, respectively. However, we recognize that many tumors lack a cytotoxic T cell infiltrate and that factors within these immunologically ‘cold’ tumors can promote T cell exclusion12. In melanoma, for instance, WNT/β-catenin signaling induces T cell exclusion13. Identification of immunomodulating pathways is critical to guide new therapeutic strategies.

In this study we aim to 1) explore diversity in the immune contexture of GEA subtypes, and 2) identify candidate mediators of T cell exclusion to build a foundation for the development of novel immunotherapeutic interventions.

Materials and Methods

Patient series

Tumor-immune characterization was performed on two separate series. The first series consisted of genomic and transcriptomic data from 453 GEAs with annotated GEA subtypes, i.e. EBV (n=30), MSI (n=75), CIN (n=297), and GS (n=51) from TCGA14.

The second series was obtained from archival formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) surgical resected untreated non-metastatic GEAs from CIN (n=26) and GS (n=18) cases from Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA) and MSI (n=14) and EBV (n=13) cases from the University of Varese and Pavia7. EBV status was determined by in situ hybridization using probes against Epstein-Barr encoded RNA 1 (EBER1). MSI was assed using focused PCR analysis of the BAT25, 26, BAT40, D5S346 and D2S123 loci respectively.as previously described7. CIN cases were defined as MSS/EBV-negative esophageal adenocarcinomas. GS cases were defined as MSS/EBV-negative diffuse type gastric cancers.

Immune analyses with immunohistochemistry

Digital immune cell analyses

Immunohistochemistry was performed using antibodies against CD4 (Dako;#M7310), CD8 (Dako;M7103), CD20 (Dako;#M0755), CD45 (Dako;#M0701), CD68 (Dako;#M0876), FOXP3 (Biolegend;#320102), CD33 (Leica;#6029028), PD-1 (Cell Marque;#315M-95), T-bet (Santa Cruz;#sc-21749), cytokeratin (CKAE1/AE3-Dako;#3515), CD208 (NOVUS;#DDX0191P-100), and PNAd (BD Pharmingen-#553836). Slides were systematically evaluated (JH) and analyzed with Aperio ImageScope software. Immune cells (number of cells or staining intensity per mm2) at the tumor border and tumor center were analyzed separately.

PD-L1 was stained (clone 405.9A11) as previously described7 and was considered positive if ≥1% of tumor or stroma cells had membranous staining.

NanoString mRNA expression analyses.

RNA was extracted from FFPE slides using the Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE kit (Qiagen-#80234) using manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was analyzed using the nCounter® PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel (Nanostring Technologies). Data was normalized and analyzed using nCounter Advanced Analysis software (version 2.0).

Genomic annotation of CIN cancers with target sequencing

DNA from GEA resection specimen was subjected to target sequencing of exons of 243 genes commonly altered in GEA by a previously described method15.

Computational analyses

Immune cell annotation:

The Immune cell populations were calculated in TCGA samples using a computational algorithm, TIMER16, to estimate the abundance of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, B cells, macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells (DC) from mRNA sequencing data.,Hierarchical clustering of CD4 and CD8 scores analysis was used to annotate immune hot and cold status.

Genomic annotation:

Aneuploidy scores such as arm-level events and focal copy number variations (CNV) were calculated as before17. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed based on the gene sets obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (mSigDB). Neoantigen prediction was performed as previously described18.

Statistical analyses

Associations between numerical and categorical data were analyzed using two-tailed Student’s t-test and Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate with SPSS (version 24) or GraphPad Prism (version 6.0). Associations between immune cell number and mutational load or copy number variations were analyzed using Spearman’s rank order correlation and one-way Anova. All P-values are two sided and considered statistically significant when <0.05. Associations between genomic events and immune scores were corrected by Benjamini-Hochberg method for multiple comparisons.

Results

Profound differences in immune infiltration between GEA subtypes.

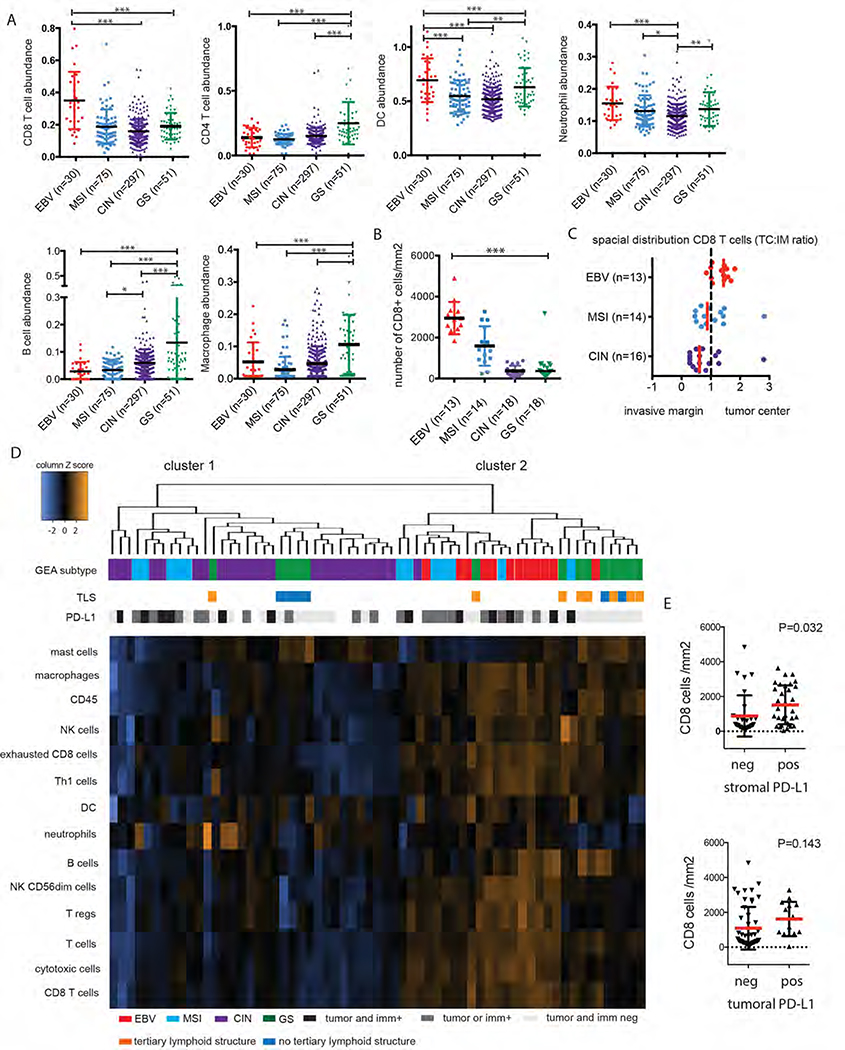

To evaluate the GEA immune tumor microenvironment (TME) we first performed an immuno-genomic analyses using 453 GEAs from the TCGA comprising all 4 distinct GEA subtypes (EBV (n=30), MSI (n=75), CIN (n=297), and GS (n=51). We next utilized a computational algorithm, TIMER16, to estimate the abundance of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, B cells, macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells (DC) from mRNA sequencing data, and confirmed highest CD8+ T cells abundance in EBV+ GEAs (P<0.001, Figure 1A). Interestingly, GS GEAs were enriched with CD4+ T cells, B cells and macrophage infiltrates (P<0.001). CIN tumors were significantly less inflamed compared to all other subtypes.

Figure 1.

The tumor immune microenvironment (TME) of GEA subclasses.

A) TIMER analysis of TCGA mRNA sequencing data shows heterogeneity of immune infiltration between GEA subtypes. B) IHC/digital image analysis using CD8 antibodies confirms lower CD8+ T cells in CIN and GS subclass. C) CD8 T cell have a tumor infiltrating character in EBV+ and MSI cancers (ratio cell density at TC tumor center compared to invasive margin (IM) >1) while the opposite is observed for CIN GEAs (ratio<1).

D) Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of Nanostring cell type annotation data identfies 2 large clusters. CIN GEAs form cluster 1 together with half of diffuse/GS cases and half of MSI GEAs. EBV and the other 50% of MSI group in cluster 2, together with diffuse/GS cases of which the majority has tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS). E) Stromal PD-L1 expression (IHC), but not tumoral PD-L1 expression, was found to be associated with intratumoral CD8+ T cells. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001

Additional analyses were performed using a second series of FFPE resection specimens of stage II and III GEAs spanning the 4 molecular subclasses. We first confirmed high CD8+ T cell infiltration in the EBV (n=13) and MSI (n=14) subtypes, which was lower in CIN (n=18) and diffuse gastric cancers, representing the GS subtype (N=18)(P<0.0001, Figure 1B). Spatial immune analyses identified that in EBV GEAs, CD8+ T cells densities are highest at the tumor center compared to invasive margin (ratio cell densities at tumor center (TC): invasive margin (IM)>1) (Figure 1C and supplementary Figure 1). By contrast, the opposite was observed for most CIN (14/18) GEAs where CD8+ T cells cluster mainly at the invasive margin (Figure 1C and 2D). Due to the discohesive growth pattern of diffuse cancers, an invasive margin could not be identified thus precluding this assessment of T cell localization.

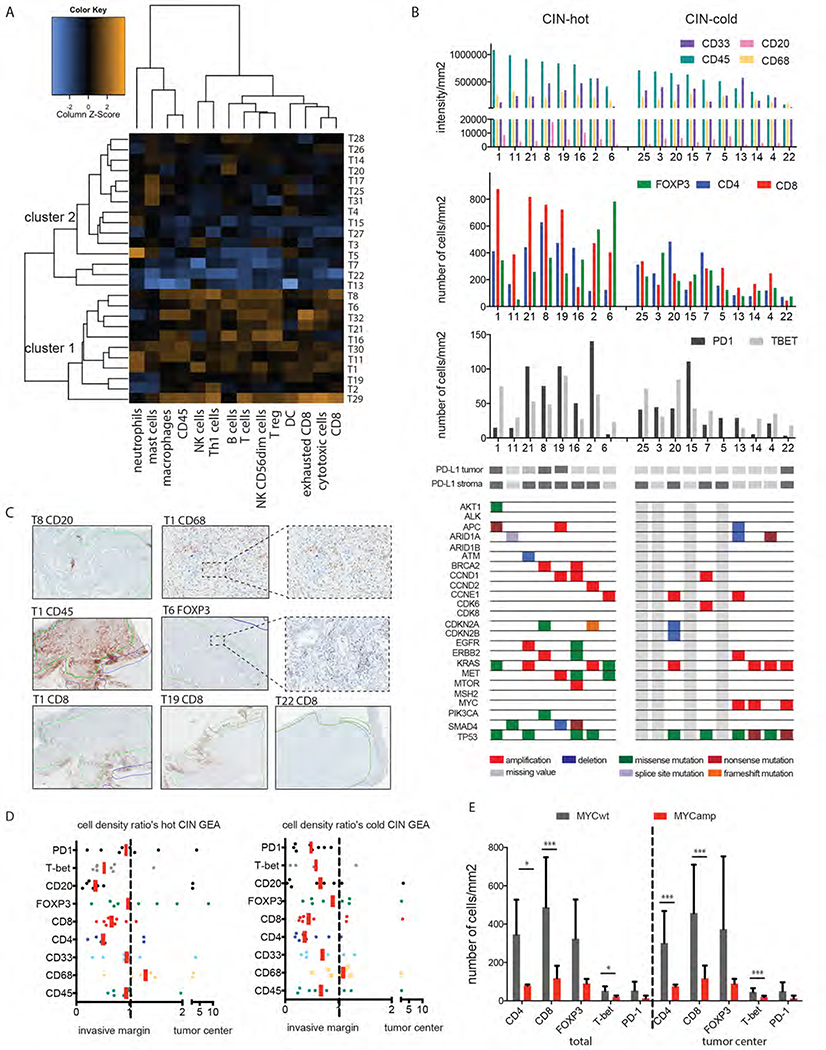

Figure 2. A).

A) unsupervised hierarchical clustering of cell type annotation data from Nanistring mRNA analysis of the CIN archival FFPE cohort reveals a ‘CIN-hot’ (cluster 1) and ‘CIN-cold’ (cluster 2) cluster.

B) The ‘CIN-hot’ (left) and ‘CIN-cold’ (right) clusters were further analyzed by IHC and a genomic GEA targeted sequencing panel, presented in order of decreasing CD45 count (left to right). (C) Examples of IHC and the digital analysis process are shown. Green: tumor area, blue, invasive margin

D) Cell density ratio’s (cell density at tumor center: cell density at invasive margin) show accumulation of most immune cell subsets at the invasive margin, except CD68+ macrophages and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells which are distributed more evenly over tumor margin and center E) MYC amplification (amp) is associated with a lower number of CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and T-bet+ (Th1 proinflammatory) T cells compared to MYC wildtype (WT) tumors. * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001

As expected PD-L1 positivity of tumor and/or immune cells was most prominent in MSI (12/14, 86%) and EBV GEAs (9/13, 69%), followed by CIN (61%, 11/18) and diffuse/GS type GEAs (1/18, 6%, P<0.001) and was associated with a higher number of CD8 T cells/mm2 (P=0.03,Figure 1E).

We then performed immune profiling using Nanostring mRNA expression analyses on our FFPE cohort. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering showed that diffuse/GS gastric cancers cluster together with EBV and many MSI GEAs (Figure 1D). Interestingly, about half of all MSI GEAs cluster with less inflamed GEAs in cluster 1,,indicating heterogeneity within MSI GEAs. Although limited by a small sample size, there was no difference in age, gender or anatomic site between MSI cases in both clusters. Using the larger TCGA dataset, no association between CD8+ T cell abundance and neoantigen load within MSI cancers was found.

We next performed a differential cell type analyses between GEA subtypes, finding that CIN tumors have the lowest density of Th1 T cells and exhausted CD8 cells among all subtypes (P<0.0001) and lowest NK cells and regulatory T cells, compared to MSI and EBV (P<0.001, supplemental Figure 2). Pathways related to cytoxicity, NK cell function, and antigen processing were most enriched in MSI and EBV GEAs (P<0.0001). Interestingly, diffuse/GS cases had higher complement and microglial function scores compared to the other subtypes (P<0.0001). As CIN and GS GEAs have the lowest responses to ICI, we decided to focus further analyses on these subtypes.

CIN GEAs have a heterogeneous immune microenvironment.

We first evaluated CIN GEAs and observed large variation in immune composition across these tumors. Nanostring mRNA profiling revealed that 11/25 (44%) CIN cases are more strongly inflamed, the ‘CIN-hot’ group compared to the remaining 14/25 (56%); the “CIN-cold’ group (Figure 2A). IHC and digital slide analyses confirmed a 12-fold and 20-fold difference in CD45+ cells and CD8+ T cell per mm2 between CIN GEAs with the highest (nr 1) and lowest number (nr 22) of immune cells. Immune cell densities were often positively interrelated (supplemental Figure 3) and more prevalent at the invasive margin (IM) compared to the tumor center (TC) (TC:IM ratio< 1; Figures 2C–D).. CD68+ macrophages (TAMs) showed more consistent levels across all CIN GEAs (Figure 2B) and a more homogeneous distribution within the tumor.

Genomic differences between immunological hot and cold CIN GEAs.

To search for structural differences between CIN-hot and CIN-cold GEAs we first annotated CIN GEAs genomically with a target sequencing panel and identified that MYC amplification correlated with a lower CD8+ and CD4+ T cell numbers at the invasive margin and within the tumor (P=0.001 (threshold P<0.002) Figure 2E). Similar correlations were not observed for other recurrent somatic aberrations.

We next utilized CIN tumors from the TCGA cohort (n=297) to identify genome-immune associations. We first asked if neoantigen load predicts T cell infiltration in CIN tumors but found an inverse correlation with CD8+ T cells abundance (P=0.04) (supplemental Figure 4). Also no association between neoantigen levels and levels of cytolytic effectors granzyme (GRZA) and perforin (PRF1) (CYT score) was identified, suggesting the presence of alternative mechanisms impacting immune cell infiltration.

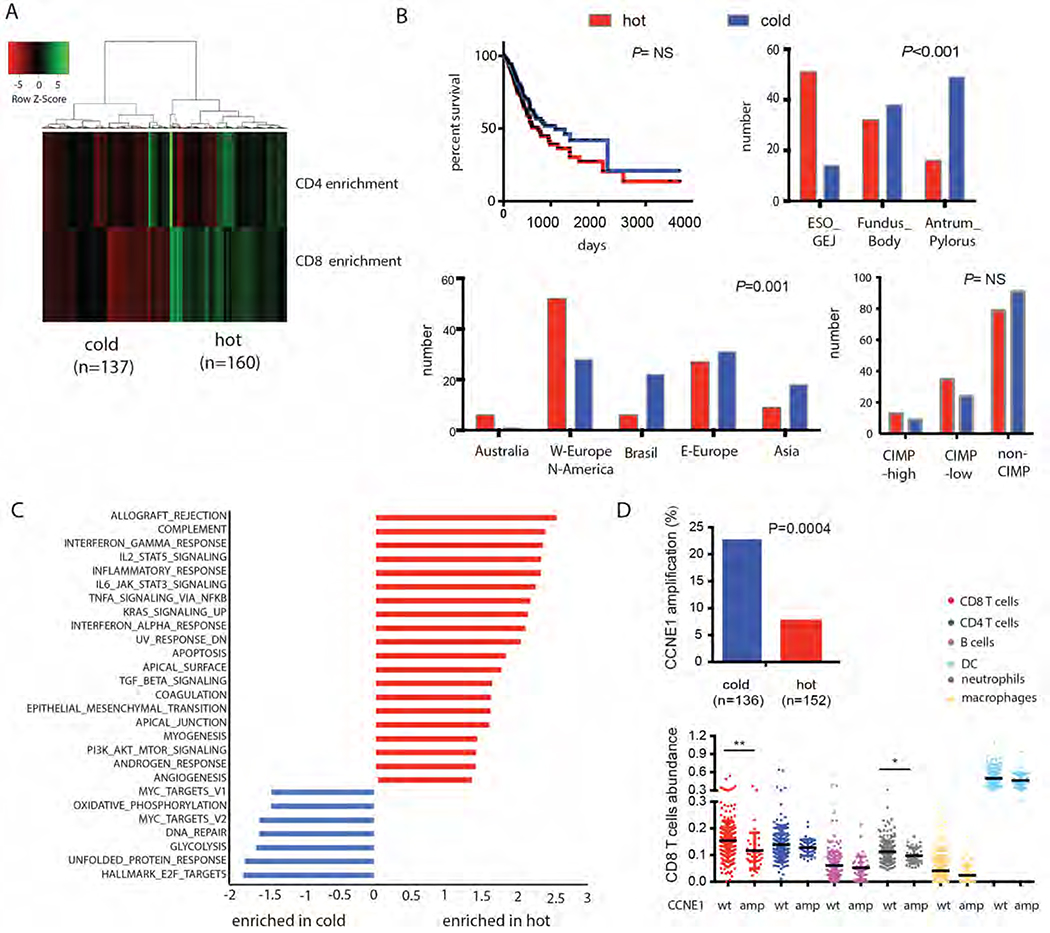

Inspired by the distinct immune clusters among CIN GEAs within our FFPE cohort we categorized TCGA CIN tumors as immunological ‘hot’ (160/297= 53.9%) or ‘cold’ (137/297, 46.1%) based on hierarchical clustering using CD4 and CD8 abundance scores (Figure 3A). Immunological hot and cold groups did not differ in age, gender or tumor stage, or survival (Figure 3B). Interestingly, we observed geographical differences between immunological ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ cases. While patients from Asia and Brazil were overrepresented in immunological cold tumors, tumors from Australia, North-America and Western-Europe were most frequently immunological hot (P=0.0001). Furthermore, immunological cold tumors had a more distal tumor location compared to hot tumors (P<0.001).

Figure 3.

Differential analyses of ”CIN-hot” and “CIN-cold” phenotypes using TCGA data.

A CIN samples were divided into ‘CIN-hot’ and ‘CIN-cold’ groups based on CD4 and CD8 enrichment scores (B), which was not significantly associated with overall survival Immunological cold tumors occurred more often patient from Asian, Western-European and Brazilian descent and were more often in the distal stomach.

C) Gene set enrichment analysis of TCGA mRNA expression data comparing CIN-hot GEAs and CIN-cold GEAs. Red: pathways enriched in the CIN-hot. Blue: pathways enriched in the CIN-cold GEAs.

D) Cyclin E1 (CCNE1) was one of the most differentially amplified genes between hot (red) and cold (blue) CIN tumors, and associated with a lower CD8 T cells abundance score.

* p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01

Immunological cold CIN tumors have up-regulation of cell cycle regulatory pathways

To identify potential regulators of T cell exclusion we performed gene set enrichment analyses (GSEA) comparing hot and cold TCGA tumors. As expected, gene sets associated with inflammatory response such as interferon gamma response signaling were among the most enriched in CIN–hot cancers (Figure 3C, in red). Interestingly, KRAS signaling was enriched as well, consistent with findings that KRAS mutation induces CD8+ T cell responses in lung cancer19. Immunological cold tumors, however, showed very distinct expression patterns (Figure 3C in blue) with enriched pathways involved in cell cycle regulation and proliferation, such as MYC and E2F target pathways, and gene sets associated with oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis and an unfolded protein response. In contrast to our FFPE series, MYC amplification by itself was not associated with T cell enrichment in the TCGA cohort. GISTIC analyses, however, did identify cell cycle regulator Cyclin E1 (CCNE1) as one of the most differential amplified genes being present in 22.8% of immune cold CIN GEAs and 7.9% of immune hot GEAs (P=0.0004, (threshold P<0.002)) and associated with a lower CD8+ T cell and neutrophil scores (P=0.002, and 0.02 respectively, Figure 3D). This association was not observed for recurrent amplifications of ERBB2, KRAS, GATA6, and VEGFA and cell cycle regulators CDK4, CDK6 and CCND1. With MutSig analyses of mutations in hot and cold CIN cohorts, no significantly differentially mutated gene was identified (data not shown).

As CCNE1 is a cell cycle driver that induces CIN20 and CIN has been associated with immune cell exclusion21 we questioned whether CCNE1 amplification is specifically associated with T cell exclusion or whether this is a reflection of a general state of aneuploidy. Indeed, we found that the number of focal copy number variations (CNVs) also showed an inverse association with CD8+ T cell abundance (P=0.005), which was not observed for arm level CNAs (Supplemental Figure 3B). As CCNE1 amplification is related to a higher number of focal CNAs, it is not known whether CCNE1 amplification itself or a higher level of chromosomal instability drive T cell exclusion in these GEAs.

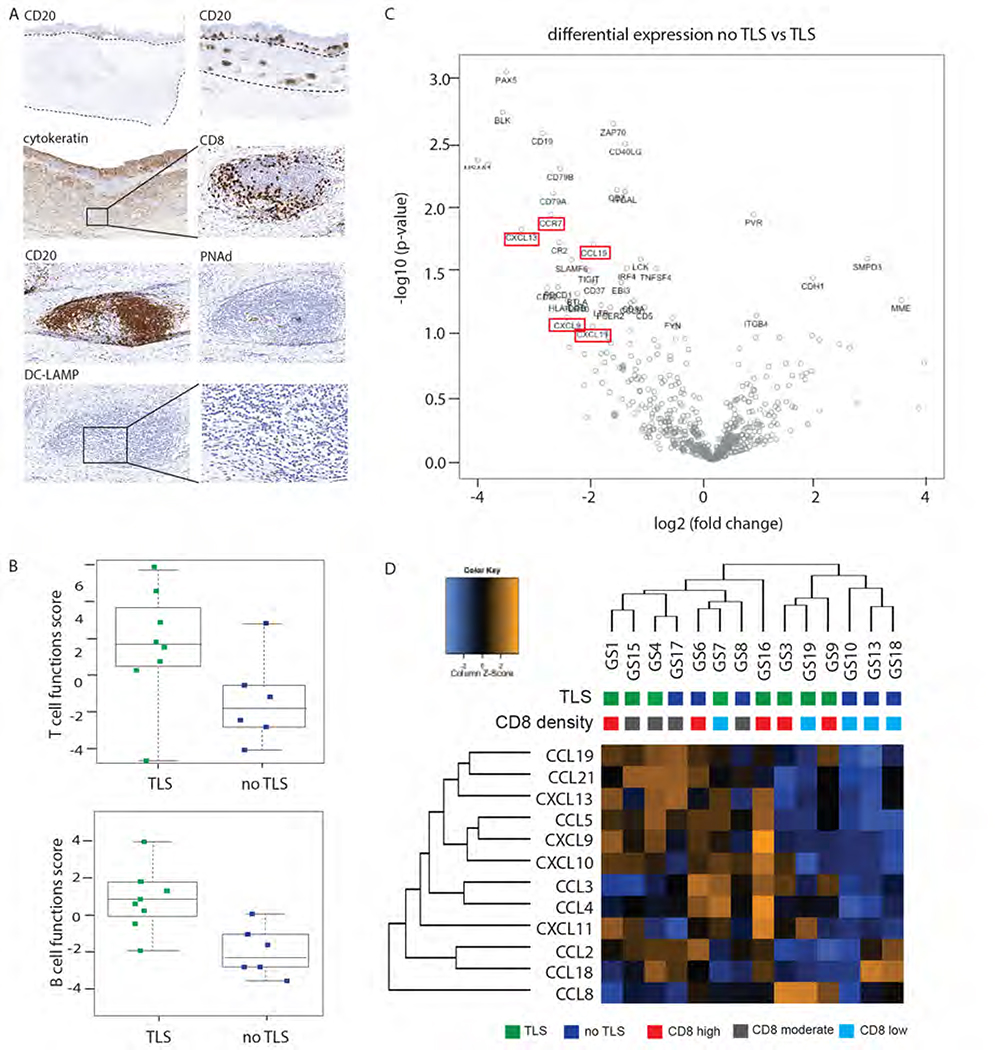

Diffuse type gastric cancers have enrichment of intratumoral tertiary lymphoid structures

We next evaluated diffuse/GS gastric cancers in our FFPE cohort and observed CD8+ T cells aggregates in 10/18 diffuse/GS GEAs which showed structural similarity to tertiary lymphoid structures (TLSs) (Figure 4A and supplemental Table 1). These intratumoral TLSs were not observed in CIN GEAs. TLSs usually provide intratumor sites for T antigen presentation by dendritic cells to generate effector immune cells22. We confirmed with IHC that these aggregates were enriched with DC-LAMP (CD208) positive dendritic cells, contain high endothelial venules (HEV), which enable migration of peripheral T cells into the lymphoid structures, and CD20+ B cells, which were in juxtaposition of CD8+ T cells zones, all characteristic signs of TLSs (Figure 5A).

Figure 4. A).

A) 50% diffuse type/GS GEA lymphoid aggregated which we further characterized as tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) by additional IHC (A; PNAd, peripheral node addressin, marker for high endothelial venules; DC-LAMP, dendritic cell lysosomal associated membrane glycoprotein, marker for mature DCs).

B) Presence of TLSs in diffuse type/GS GEA was associated with a higher T cell and B cell function score.

C) Vulcano plot showing the most differentially expressed genes in diffuse type/GS GEA with and without TLS.

D) The 12-chemokine gene expression signature is enriched in some but not all diffuse/GS GEA with TLS formation.

We next evaluated the diffuse/GS tumors with Nanostring and confirmed robust presence of markers of B and T cell populations in tumors with TLS formation and enrichment of lymphocyte attractant CXCL13 (P=0.007; Figure 4C–D). Additionally, we found chemokine CCL19 and its receptor CCR7, which play a role in T cell and DC homing, enriched in diffuse/GS GEAs with TLSs (P=0.005 and 0.009 respectively). The 12-chemokine gene expression signature that characterizes TLSs in melanoma and lung cancers23 was enriched in some but not all diffuse/GS cases with TLSs (Figure 4D), which might reflect the different stages of lymphoid neogenesis. All together, these results show that over half of diffuse/GS GEA show signs of an initiated antitumor immune response, consistent with our earlier observation that many diffuse/GS cases co-cluster with EBV+ and MSI GEA’s (Figure 1D, cluster 2). Although the level of activation of the antitumor immune response in these cancers needs further evaluation, these results suggest that the subset of diffuse/GS cases with TLS formation are promising candidates for further immunomodulatory agents.

Discussion

GEA is heterogeneous disease with distinct molecular subtypes. An increasing number of studies have demonstrated prognostic value of the TCGA classification24 and differential responsiveness to ICI7. Especially in CIN and GS GEAs, ICI-results are disappointing. As a foundation to improved immunotherapeutic strategies we evaluated the immune TME across GEA subsets and identified large variation in immune infiltrate between and within GEA subtypes. Using different cohorts, EBV+ GEAs were consistently T cells infiltrated. Interestingly, we observed a dichotomy in immune infiltration of MSI GEAs in which half of MSIs have a EBV-like TME and half have a less inflamed CIN-like TME. Although a less robust T cell infiltrate is not necessarily a determinant of failure of ICI, this diversity within MSI is consistent with the failure of ICI efficacy in some MSI cancers25. While more studies of the immune diversity of MSI cancers are needed, we opted to focus on CIN and GS GEA given the lower efficacy of ICI therapy.

Analyses of the CIN microenvironment identified that CIN GEAs not only have lower T cell densities but that T cells are mostly concentrated at the invasive margin. Although this detailed immunohistochemical analyses was limited to 18 patients, the pattern was consistently present and suggests that T cell exclusion, rather than T cell suppression, is a dominant immune suppressive mechanism. Furthermore, we noted that the patients with relative higher T cell density were more often from Western countries and had a more proximal tumor location. This difference is consistent with a previous study comparing immune signature of Asian and non-Asian gastric cancer cohorts26. Whether these differences reflect ethnic or environmental differences will need to be established. While these results may be apparently contradictory to results showing that Asian GEAs populations have increased sensitivity to ICI compared non-Asian population27, the CIN subtype is more predominant within Western cohorts. When stratified by subtype, CIN GEAs within Asian population were also minimally responsive to ICI10.

In our attempt to unravel mechanisms of T cell exclusion in CIN GEAs we found CD68+ myeloid cells and neutrophils to be prominent immune cell populations. Although we were not able to detail the sub-phenotype of these myeloid cells, M2 macrophages, myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and neutrophils can have strong immune suppressive properties12,28. Furthermore, using orthogonal genomic data, we identified that T cell poor CIN GEAs have enrichment of MYC pathway activation, which is also observed in other cancer types29. Indeed in lymphoma, pancreatic cancer and lung cancer mouse models MYC activation promtes influx of macrophages and neutrophils30 and loss of T cells, B cells, and NK cells29,31.

Another finding was the association of low T cell scores with amplification of cell cycle regulator cyclin E1 (CCNE). CCNE1 has not been identified as driver of immune exclusion. However CCNE1 amplification has been implicated as an instigator to increased aneuploidy, a tumor characteristic that has been associated with a T cell suppressed microenvironment21, making it less clear whether CCNE1 itself or enhanced CIN with Cyclin E1 overexpression promotes immune cell exclusion. It is not known how aneuploidy induces T cells exclusion but one explanation is immune suppression from the unfolded protein response (UPR), itself activated by proteomic stress (ER stress) in CIN32. ER stress has pro-inflammatory but also immune suppressive effects33 upon innate immune cell populations which inhibits their antigen presenting capacity. Alternatively, CIN could inhibit the immune response by perturbing neoantigen presentation due to a competitive disadvantage of neoantigens compared to excessive expression of other proteins34.

Collectively, these data suggest CIN GEAs have a complex suppressed tumor immune microenvironment that may need a multifactorial approach for immune activation. Targeting immune suppressive macrophages or neutrophils by neutralizing granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) or inhibiting colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) or targeting immune suppressive cell cycle or MYC pathways are potential strategies.

Beyond CIN, we also evaluated the TME of diffuse type/GS gastric cancers and found recurrent intratumoral TLSs. TLSs can be considered as antibody ‘factories’ at the tumor site meant to fuel an inflammatory response containing high numbers of B cells, T cells and dendritic cells22. These features may explain why cancers with intratumoral TLSs have a more favorable prognoses and respond well to immunotherapy35,36. As responses to ICI in diffuse type GEAs were not overwhelmingly positive8, it remains to be identified if metastatic diffuse type cancer also harbor TLSs. Nevertheless, given the established associations of TLS formation with immune cell involvement, TLS+ diffuse gastric cancers are promising candidate for immunomodulatory strategies.

Although future studies are needed to determine the best immunomodulatory approach in CIN and diffuse/GS GEA, these results illustrate the extent of heterogeneity of the immune contexture in gastric cancer and argue for the need for more personalized targeted or combination immunotherapies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

There is large heterogeneity in the immune contexture of gastro-esophageal adenocarcinomas (GEA) subtypes.

Chromosomal instable GEAs are often T cell excluded, which is associated with enhanced MYC and cell cycle pathways.

Genome stable cancers, contrarily, often have tertiary lymphoid structures.

This study argues for more personalized immunotargeting strategies in gastroesophageal cancer treatment.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Specialized Histopathology Core at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center for their support.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from Merck to AJB. SD is supported by the Dutch Cancer Society, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), ASCO and Oncode Institute. SO receives funding from USA National Institutes of Health (grant number R35 CA197735).

This study was supported by research funds from Merck to A.J.B. A.J.B has funding from Merck, Bayer and Novartis, is an advisor to Earli and Helix Nano and a co-founder of Signet Therapeutics. SJR receives research funding from Merck, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Affimed, and KITE/Gilead.

Abbreviation:

- MSI

microsatellite instability

- EBV

Epstein-Barr Virus

- CIN

chromosomal instable

- GS

genome stable

- GEA

gastro-esophageal cancer

- TLS

tertiary lymphoid structures

- ICI

immune checkpoint inhibitors

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- TAM

tumor associated macrophages

- IT

intratumoral

- IM

invasive margin

Footnotes

Disclosure

All remaining authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008; 3581:36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman GJ, Long a J, Iwai Y et al. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J. Exp. Med. 2000; 1927:1027–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akyala AI, Verhaar AP, Peppelenbosch MP. Immune checkpoint inhibition in gastric cancer: A systematic review. J. Cell. Immunother. 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jocit.2018.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW et al. Safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer: Phase 2 clinical KEYNOTE-059 trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bass AJ, Thorsson V, Shmulevich I et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature 2014; 5137517:202–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature 2017; 5417636:169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Derks S, Liao X, Chiaravalli AM et al. Abundant PD-L1 expression in Epstein-Barr Virus-infected gastric cancers. Oncotarget 2016. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim ST, Cristescu R, Bass AJ et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat. Med. 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thorsson V, Gibbs DL, Brown SD et al. The Immune Landscape of Cancer. Immunity 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim ST, Cristescu R, Bass AJ et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat. Med. 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribas A Adaptive Immune Resistance : How Cancer Protects from Immune Attack. Cancer Discov. 2015; 5:915–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gajewski TF, Schreiber H, Fu Y-X. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Immunol. 2013; 1410:1014–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature 2015; 5237559:231–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J, Bowlby R, Mungall AJ et al. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature 2017. doi: 10.1038/nature20805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pectasides E, Stachler MD, Derks S et al. Genomic heterogeneity as a barrier to precision medicine in gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2018. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bo Li, Eric Severson, Jean-Christophe Pignon et al. Comprehensive analyses of tumor immunity: implications for cancer immunotherapy. Genome Biol. 2016:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Sethi NS, Hinoue T et al. Comparative Molecular Analysis of Gastrointestinal Adenocarcinomas. Cancer Cell 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miao D, Margolis CA, Vokes NI et al. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint blockade in microsatellite-stable solid tumors. Nat. Genet. 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0200-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busch SE, Hanke ML, Kargl J et al. Lung Cancer Subtypes Generate Unique Immune Responses. J. Immunol. 2016. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teixeira LK, Carrossini N, Sécca C et al. NFAT1 transcription factor regulates cell cycle progression and cyclin E expression in B lymphocytes. Cell Cycle 2016. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1203485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davoli T, Uno H, Wooten EC, Elledge SJ. Tumor aneuploidy correlates with markers of immune evasion and with reduced response to immunotherapy. Science (80-.). 2017. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teillaud JL, Dieu-Nosjean MC. Tertiary lymphoid structures: An anti-tumor school for adaptive immune cells and an antibody factory to fight cancer? Front. Immunol. 2017. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Messina JL, Fenstermacher DA, Eschrich S et al. 12-chemokine gene signature identifies lymph node-like structures in melanoma: Potential for patient selection for immunotherapy? Sci. Rep. 2012; 2:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sohn BH, Hwang JE, Jang HJ et al. Clinical significance of four molecular subtypes of gastric cancer identified by The Cancer Genome Atlas project. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrock AB, Ouyang C, Sandhu J et al. Tumor mutational burden is predictive of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in MSI-high metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin SJ, Gagnon-Bartsch JA, Tan IB et al. Signatures of tumour immunity distinguish Asian and non-Asian gastric adenocarcinomas. Gut 2015; 6411:1721–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng L, Wu YL. Immunotherapy in the Asiatic population: Any differences from Caucasian population? J. Thorac. Dis. 2018. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.05.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, De Visser KE. Neutrophils in cancer: Neutral no more. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wellenstein MD, de Visser KE. Cancer-Cell-Intrinsic Mechanisms Shaping the Tumor Immune Landscape. Immunity 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sodir NM, Swigart LB, Karnezis AN et al. Endogenous Myc maintains the tumor microenvironment. Genes Dev. 2011. doi: 10.1101/gad.2038411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Layer JP, Kronmüller MT, Quast T et al. Amplification of N-Myc is associated with a T-cell-poor microenvironment in metastatic neuroblastoma restraining interferon pathway activity and chemokine expression. Oncoimmunology 2017. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1320626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grootjans J, Kaser A, Kaufman RJ, Blumberg RS. The unfolded protein response in immunity and inflammation. Nat. Publ. Gr. 2016; 168:469–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Bettigole SE, Glimcher LH. Tumorigenic and Immunosuppressive Effects of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Cancer. Cell 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granados DP, Tanguay PL, Hardy MP et al. ER stress affects processing of MHC class I-associated peptides. BMC Immunol. 2009. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colbeck EJ, Ager A, Gallimore A et al. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures in Cancer: Drivers of Antitumor immunity, immunosuppression, or Bystander Sentinels in Disease? Front. Immunol. 2017; 8:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dieu-Nosjean M-C, Goc J, Giraldo NA et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer and beyond. Trends Immunol. 2014; 3511:571–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.