Abstract

Background

According to expert consensus, the time interval between Hymenoptera venom immunotherapy (VIT) injections can be extended up to 12 weeks, without significant impact on efficacy and safety. However, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic caused longer delays, and no recommendations are available to manage this huge extension.

Objectives

To provide advice on how to resume VIT safely after a long delay from the last injection considering the potential risk factors for side effects, without starting again with the induction phase.

Methods

All the patients who delayed VIT because of the pandemic were consecutively enrolled in this single-center study. The time extension was decided according to their risk profile (eg, long prepandemic time interval, severe pre-VIT reaction, older age, multitreatments), and correlation analyses were performed to find potential risk factors of side effects.

Results

The mean delay from the pre- (7 weeks) to the postpandemic VIT interval (15.5 weeks) was 8.5 weeks. The total amount of the prepandemic VIT maintenance dose was safely administered in 1 day in 78% of patients, whereas only 3, of 87, experienced side effects, and their potential risk factors were identified in bee venom allergy and recent VIT initiation.

Conclusions

In a real-world setting, long VIT delays may be safe and well tolerated, but more caution should be paid in resuming VIT in patients with long prepandemic maintenance interval, severe pre-VIT reaction, recent VIT initiation, older age, multidrug treatments, and bee venom allergy. This is useful in any case of long, unplanned, and unavoidable VIT delay.

Key words: COVID-19 pandemic, Hymenoptera venom allergy, Maintenance interval, Systemic reactions, Venom immunotherapy

Abbreviations used: COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; HVA, Hymenoptera venom allergy; MI, Maintenance interval; REMA, Red Española de Mastocitosis (Spanish Network on Mastocytosis); SE, Side effect; SR, Systemic reaction; STL, Serum tryptase level; VIT, Venom immunotherapy

What is already known about this topic? The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic raised the need to extend venom immunotherapy (VIT) time intervals safely. However, no guidelines are currently available on how to manage long extensions of intervals between VIT administrations (ie >3 months).

What does this article add to our knowledge? Our results show that long VIT delay may be tolerated in clinical practice, if key risk factors are considered: bee venom, long time interval between injections, severe pre-VIT reaction, date of VIT initiation, age, multitreatments.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? A safe and effective protocol to resume VIT after a long interruption is useful in case of unexpected delays in treatment. A new build-up phase may be safely avoided in most cases, with compliance and cost advantage.

Introduction

Hymenoptera stings can induce allergic systemic and occasionally fatal reactions.1 Subcutaneous venom immunotherapy (VIT) is the only disease-modifying treatment as it lessens the risk of a subsequent systemic reaction (SR), prevents morbidity, and improves health-related quality of life.2 Many treatment protocols for the VIT induction phase have been designed, varying with respect to the number of injections, venom doses, and time needed to reach the protective dose. For example, a conventional regimen means increasing doses at weekly intervals for outpatients, whereas the induction phase of rush regimens lasts 4 to 7 days, and the ultrarush protocol maintenance dose is reached within 1 to 2 days or within a few hours.

In Europe, VIT may be performed with aqueous (nonpurified or purified) extracts and depot preparations of Hymenoptera venoms, the last being used only for the conventional build-up and maintenance schedule. Many European allergists switch to depot preparations following the updosing phase with an aqueous extract.1

According to expert consensus, injections are usually given every 4 weeks in the first year of treatment, every 6 weeks in the second year, and in case of a 5-year treatment every 8 weeks from year 3 to 5.2 If lifelong treatment is necessary, extending the maintenance interval (MI) to 3 months may be relevant in terms of convenience and economic savings, because it does not seem to reduce effectiveness or increase side effects (SEs).2 , 3

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, allergists and immunologists continued to play their important role in the prevention of venom anaphylaxis,4 especially in the management of VIT, its delays in administration, and the need to reduce the hospital admissions at the same time. Currently, there are suggestions on how to behave in the event of a pandemic,4, 5, 6, 7 without a detailed approach on how to resume VIT after a long delay from the last injection, avoiding to start VIT again.

The aim of the present study was to share the experience of a single specialized allergy unit in Italy on this topic, focusing on the key factors taken into account to safely extend the time intervals between VIT injections limited to the period of the pandemic, and on the characteristics/risk factors of patients who experienced SEs because of that extension.

Methods

This study consecutively enrolled, over a period of 3 months, all patients with allergy treated with maintenance VIT, who delayed their shots because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our Allergy Clinic collects patients coming from central and southern Italy and is specialized in performing rush and ultrarush VIT protocols.

Whenever discontinuation was not recommended or patients preferred to continue VIT because of quality-of-life issue, the date of the next appointment and the number of VIT shots were decided on the basis of several patient's features, like the pre-VIT severity reaction, diagnosed or potential mast cell disorders based on a positive REMA score (Red Española de Mastocitosis - Spanish Network on Mastocytosis),8 skin testing, age, duration of VIT, type of Hymenoptera venom allergy (HVA)/venom extract, time interval between VIT injections before the COVID-19 pandemic (prepandemic MI), comorbidities, and pharmacological treatments.

Before resuming VIT, all patients underwent a medical examination, and spirometry and/or electocardiogram were performed if necessary. A venous access was also placed, and the anesthesiologist was always alerted.

Patients were not allowed to attend the visit in case of quarantine or previous contacts with COVID-19 cases, as assessed by the phone contact before the visits. Each patient was screened for COVID-19 potential infection/exposure with epidemiological interviews and body temperature check at entrance, as per hospital's COVID-19 contingency plan, and provided with disinfectant and personal protective equipment. During the visits, social distancing was respected whenever possible.

A post hoc analysis was performed to analyze the relationship between the delay in VIT administrations due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the key baseline characteristics of patients considered for the risk assessment of the VIT time interval prolongation (Pearson correlation or Spearman test, when applicable, and ANOVA test for VIT duration). The prepandemic MI is defined as the original time interval between VIT injections, before the pandemic. The postpandemic MI is the new time interval between VIT injections, which was prolonged because of the pandemic; it reflects the total magnitude of the VIT interruption (ie, prepandemic MI + time extension due to pandemic). The delay is the time gap/extension between the prepandemic MI and the postpandemic MI (ie, postpandemic MI–prepandemic MI); it reflects the magnitude of the extension from pre- to postpandemic MI, and therefore how quickly the shift from pre- and postpandemic MI was done.

Furthermore, the associations between SEs and potential risk factors were analyzed (χ2 test). Log transformation was performed for not normally distributed variables, when applicable. STATA v.13 (StataCorp - College Station, Texas, USA) was used for all the analyses.

Patients gave an informed consent to the continuation of VIT and to the use of their clinical data for research purposes in an anonymous form.

Because all the interventions were part of routine clinical practice, a formal approval by the Ethical Committee was not needed and was not requested.

Results

Baseline patients' features

Of 292 patients treated with maintenance VIT, 177 (61%) respected the original appointment despite the COVID-19 pandemic, and 28 (9.6%) stopped the treatment either because of their own decision (6 subjects), or in agreement with the investigators, as eligible to VIT discontinuation1 , 2 (22 subjects). Eighty-seven patients (30%) delayed their appointments because of fear of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. The features of these patients are presented in Table I . In particular, 72% of them were males, 84% have had a history of Mueller class 3-4, 4.5% were suffering from comorbidities (mainly represented by cardiovascular diseases), and 12% were treated with antihypertensive drugs. Four patients were suffering from diagnosed mast cell disorders, while 29% of the patients showed a REMA score of 2 or more, and 10% serum tryptase level (STL) of greater than or equal to 11.5 μg/L. The mean duration of VIT was 6.1 ± 5.5 years (15% on VIT for ≤1 year), whereas the mean prepandemic MI was 7 ± 2.3 weeks (min-max, 2-12 weeks). Seventy-four percent of patients were treated with vespid venoms, 10% with 2 vespid extracts, and the remaining patients with bee venom; most of the extracts used were depot. The total maintenance dose was 100 μg in all patients but 3, in whom it was 150 μg. None of these patients was restung during the months of the pandemic. No cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection, quarantine, or contact with potential infected people have been reported among our study population.

Table I.

Baseline patients' features

| Demographic characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Median age (y) (IQR) | 56 (42-68) |

| Sex: M/F | 63/24 (72%/28%) |

| Allergy characteristics | Concomitant conditions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-VIT reaction, n (%) | Comorbidities, n (%) | 45 (52) | |

| Mueller 1 | 4 (5) | Cardiovascular | 38 (43) |

| Mueller 2 | 10 (11) | Respiratory | 7 (8) |

| Mueller 3 | 24 (28) | Mast cell disease | 4 (5) |

| Mueller 4 | 49 (56) | Diabetes mellitus | 4 (5) |

| Other | 3 (3) | ||

| Prepandemic skin reactivity (μg/mL), n (%)∗ | |||

| 1 | 29 (33) | Potential mast cell disorder (ie, REMA score ≥2), n (%) | 25 (29) |

| 0.1 | 30 (34) | ||

| 0.01 | 12 (14) | STL ≥11.5 (median, 5.4 μg/L), n (%) | 9 (10) |

| 0.001 | 10 (11) | ||

| 0.0001 | 3 (3) | Treatments, n (%) | 41 (47) |

| ACE inhibitors | 10 (11) | ||

| Venom | Sartanics | 19 (22) | |

| A | 22 (25) | Beta-blockers | 8 (9) |

| VC | 5 (6) | Calcium-channel blockers | 10 (11) |

| P | 15 (17) | Other antihypertensives | 13 (15) |

| V | 36 (41) | Cardiac (anticoagulants, antiarrhytmics) | 11 (13) |

| P + V | 9 (10) | Statins | 9 (10) |

| Asthma inhalers | 2 (2) | ||

| VIT characteristics | |

|---|---|

| VIT duration, n (%) | |

| y ≤ 1† | 13 (15) |

| 1< y ≤2 | 11 (13) |

| 2< y ≤5 | 24 (28) |

| 5< y ≤10 | 25 (29) |

| y >10 | 14 (16) |

| Overall mean VIT duration (min-max) | 6.1 ± 5.5 y (0-30) |

| Mean prepandemic VIT interval (min-max) | 7.0 ± 2.3 wk (2-12) |

| Type of extract, n (%) | |

| Aqueous | 4 (5) |

| Depot | 83 (95) |

| Restung patients, n (%)‡ | 41 (47) |

| Systemic SEs to VIT, n (%) | 1 (1) |

A, Apis mellifera; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; F, female; IQR, interquartile range; M, male; P, Polistes dominula; V, Vespula germanica; VC, Vespa crabro.

Skin test not performed in 3 children because of serological diagnosis. Mean time interval between the first postpandemic visit and the last skin test: 28.8 mo (min-max, 1 mo-5 y).

Mean VIT duration: 9 mo (min-max, 1-18 mo).

Reaction in 2 patients.

VIT during and postpandemic: Timing

The mean postpandemic MI (ie, total VIT interruption due to pandemic) was 15.5 ± 3.3 weeks; it was greater than or equal to 4 months in 56% of patients, with the longest in 8% (≥5 months; maximum, 22 weeks). The mean delay (ie, extension from pre- to postpandemic MI) was 8.5 ± 3.1 weeks, and it was 2 months or more in 59% of patients (maximum, 16 weeks) (Table II ). VIT was administered in 1 day through 3 or 4 shots in all but 1 patient, who received only 2 shots (Table III ). The same type of extract (aqueous or depot) from the pre-COVID pandemic was reused. The total amount of the prepandemic maintenance dose of venom was administered in 1 day in 78% of patients; the others received from 60% to 85% (15% of patients) or 45% to 50% (7% of patients) of the total dose on the first day, and then the maintenance dose was reached at the subsequent visit (Table III). The reasons for not reaching the total dose in 1 day, in these patients (22%), were mostly due to logistic issues related to the pandemic reorganization. Only 3 patients (3%) did not manage to tolerate the total dose in 1 single day due to SEs. All the other patients did not show any SEs, including subjects on VIT for a short time (<1 year, but >1 month) and with long VIT interruptions (up to 5.5 months).

Table II.

Postpandemic VIT interval and delay

| Prepandemic VIT interval (no. of patients) | Postpandemic VIT interval: mean weeks (min-max) | Delay∗: mean weeks (min-max) |

|---|---|---|

| Total population (n = 87) | 15.5 ± 3.3 (8-22) | 8.5 ± 3.1 (3-16) |

| Prepandemic interval <4 wk (n = 1) | 12 | 10 |

| Prepandemic interval ≥4-<8 wk (n = 45) | 14.3 ± 3.5 (8-22) | 9.0 ± 3.4 (4-16) |

| Prepandemic interval ≥8-<12 wk (n = 38) | 16.8 ± 2.5 (11-22) | 8.0 ± 2.7 (3-13) |

| Prepandemic interval = 12 wk (n = 3) | 18.3 ± 1.5 (17-20) | 6.3 ± 1.5 (5-8) |

Delay = time extension from pre- to postpandemic time interval.

Table III.

Postpandemic VIT characteristics

| No. of injections in 1 d | No. of patients (%) |

| 2 | 1 (1) |

| 3 | 53 (61) |

| 4 | 33 (38) |

| VIT dose in 1 d | No. of patients (%) |

| 100% of the total dose | 68 (78) |

| 60%-85% of the total dose | 13 (15) |

| <60% of the total dose∗ | 6 (7) |

| SEs to VIT | No. of patients (%) |

| SR | 3 (3) |

50% in 5 patients, 45% in 1 patient.

Once VIT was resumed after the long pandemic lapse, and the prepandemic dosage was reached, the MI of subsequent shots was also kept mostly at the prepandemic MI.

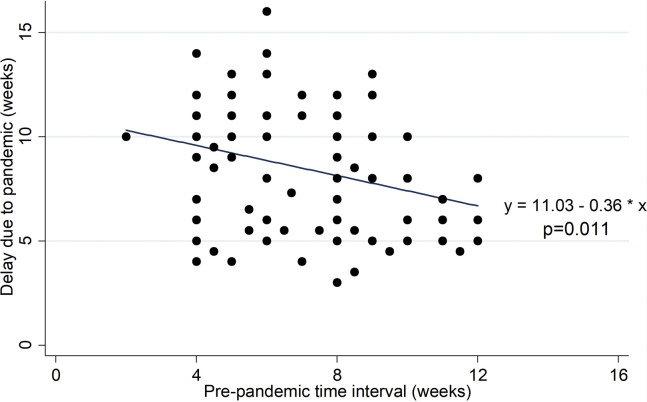

The analysis shows a linear negative correlation between prepandemic MI and the delay in VIT administration due to pandemic (Pearson r = −0.272; P = .011; 95% CI, −0.456 to −0.065) (Figure 1 ). Indeed, the mean delay decreases by an estimated 0.363 week per 1-week increase in prepandemic MI (P = .011; 95% CI, −0.639 to −0.086). Therefore, the longer the prepandemic MI, the shorter was the delay allowed in VIT administration (Table II).

Figure 1.

Correlation between injection's delay and prepandemic time interval between injections, with fitted values' line (n = 87).

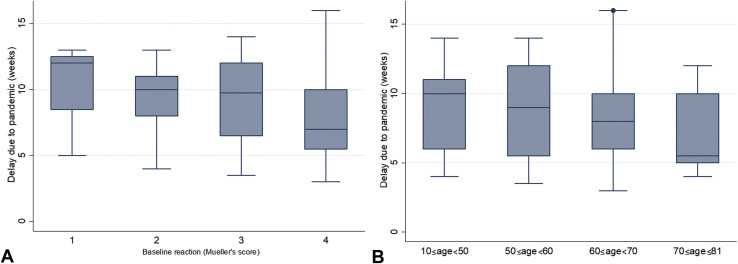

A linear negative correlation was also observed between severity of pre-VIT reaction and delay in VIT administration due to pandemic (Spearman r = −0.341; P = .001; 95% CI, −0.517 to −0.138) (Figure 2 , A). The mean delay decreases by 1.263 week per each unitary increase in Mueller's score (P = .002; 95% CI, −2.033 to −0.492).

Figure 2.

Box plot of injection's delay per (A) severity of baseline reaction to sting and (B) patients' age (n = 87).

There is a trend for a negative correlation between VIT duration and delay in VIT administration, but this correlation is not statistically significant (P = .085). This is supported by the fact that no significant differences, in terms of delay, are observed across different years of VIT duration (F = 0.69; P = .603).

Patients undergoing concomitant medications had a shorter delay (P = .041), as well as older patients (P = .017; Figure 2, B); namely, the mean delay in patients 65 years or older was 7.1 ± 2.6 weeks, compared with 9.2 ± 3.1 weeks in the younger ones.

However, no significant correlation has been observed between VIT delay and sex, type of HVA, comorbidities, prepandemic skin test reactivity, previous SEs related to VIT, abnormal STL (ie, ≥11.5 μg/L), or REMA score (ie, ≥2).

SRs during postpandemic VIT

Table IV presents the features of the 3 patients who experienced SRs after VIT delay. Among all the key baseline characteristics analyzed, SEs had a statistically significant correlation only with bee venom allergy (P = .002).

Table IV.

Characteristics of patients who reacted to VIT after the extension of the time interval between administrations

| Patient | Age (y) | Sex | VIT duration | Pre-VIT Mueller | REMA score | Reaction during VIT | Venom (extract) | Prepandemic MI | Postpandemic MI | SEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1∗ | 38 | M | 1 mo | IV | 3 | No† | Bee (depot) | 2 wk | 12 wk | Moderate oral, palmar, and plantar itching |

| 2 | 36 | M | 3 y | III | −2 | No | Bee (depot) | 6 wk | 20 wk | Mild rhinoconjunctivitis and cough |

| 3‡ | 43 | F | 12 y | IV | 2 | No | Bee (depot) | 10 wk | 20 wk | Menses-like pain |

F, Female; M, male.Key common features: bee venom allergy, depot extract, no concomitant diseases/treatments, no previous reactions during VIT.

Hobby beekeeper.

This patient tolerated a 3-d “rush” protocol with a purified aqueous extract, whereas 1 y before he was forced to stop VIT in another center because of systemic SEs during a conventional protocol using a nonpurified aqueous extract.

Beekeeper's family member.

All the 3 patients were quite young (≤43 years old) and without comorbidities or concomitant treatments.

Patient 1, a hobby beekeeper, had a history of particularly troublesome VIT before starting the therapy at our center (on March 2020), with recurrent SRs to VIT during the induction phase in another center. Consequently, he had the shortest VIT duration (ie, 1 month) and prepandemic MI (ie, 2 weeks) in our study population; all the other patients had a prepandemic MI of greater than or equal to 4 weeks. Furthermore, the skin reactivity to bee venom was very high (0.0001 μg/mL). He reported moderate oral, palmar, and plantar itching 20 minutes after the second injection on the same day (35% of the total maintenance dose), with complete remission after administration of cetirizine 10 mg and betamethasone 4 mg, but he managed to reach 50% of the total dose on the first day without further SEs. At the subsequent visit, he experienced mild palmar itching, and reached 85% of the total dose. No further events were reported at the subsequent visits, reaching the total maintenance dose.

Patient 2 had a delay due to pandemic of 14 weeks, higher than the mean delay of the total population (8.5 weeks). Rhinoconjunctivitis and mild cough appeared at the third injection (40% of the total dose), effectively treated with nasal steroids and cetirizine 10 mg. Afterwards, he reached 60% of the maintenance dose on the same day.

Patient 3 is a beekeeper's family member who reached 100% of the total maintenance dose, but experienced late SEs (ie, menses-like pain 3-4 hours after the last injection, treated at home with oral corticosteroids). The event was judged related to VIT, because the symptomatology was quite similar to that which arose before starting VIT and no other possible causes have been identified.

Discussion

This study aims at sharing our experience in resuming VIT after a long delay from the last injection, on this occasion due to the COVID-19 pandemic, because no clear indications on this topic come from national or international documents or guidelines.2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

According to literature, in case of a 5-year treatment2 or of more than 4-year treatment,3 progressively extending the MI to 3 months does not seem to increase the risk of an SR or reduce VIT effectiveness. A 6-month interval does not seem to influence VIT safety,9 , 10 but it is less effective in the case of a few years of bee VIT.9 Moreover, there is no specific study available for patients with mastocytosis with severe initial SR suggesting the maximum MI to be used in these patients.

As first results, it is of note that of 292 patients only 9.6% of them stopped VIT, 30% delayed their appointment, whereas 61% respected the original appointment despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Even excluding those patients who did not respect the fixed MI, adherence to VIT remains quite high (61%), considering that the only study available on this topic indicates an adherence rate of 83.7% by the fifth year from the start of VIT in normal situation.11

Our patients are representative of a real-life population with the most common characteristics of patients with HVA in terms of demographic, allergy and VIT characteristics, and concomitant conditions (Table I). In this population, the delay (ie, extension) from the prepandemic scheduled MI to the new postpandemic MI, due to the COVID-10 pandemic, was often remarkable (up to 16 weeks), causing not only long VIT interruptions (new postpandemic MI up to 22 weeks) but also abrupt shifts to longer MI (Table II). However, these extensions were safe and well tolerated, because only 3 patients, of 87, experienced SRs (Tables III and IV). In our opinion, the main reasons for this achievement could be (1) the protocol used for extending VIT intervals; (2) the case-by-case approach adopted for the decision making of the time extension, which was weighed against key baseline characteristics; and (3) the environment and experience in managing HVA and SRs during the treatment.

Concerning the adopted protocol, even in case of long delay, it was chosen to resume VIT without starting over with a new build-up phase. In fact, the prepandemic maintenance dose was kept and reached in 1 day in most patients (78%), with consequent avoidance of a new induction phase and therefore a higher patient compliance. The depot extract was used in almost all the patients (95%), probably contributing to the safety,2 , 12 even though the low number of aqueous extracts (4 subjects) did not allow a robust risk comparison between them. The facilities of our specialized center for HVA made this protocol feasible in a safe environment, guaranteeing the appropriate management of SEs.

As for the case-by-case approach, because the prepandemic MI already reflected potential patients' risk factors of SEs, it was the main factor that affected the decision-making process for the new postpandemic MI. It is confirmed by the clear significant correlation between pre- and postpandemic MI, reflecting the caution paid in patients who already had long time intervals between injections before the pandemic; namely, a long prepandemic MI was correlated with shorter delays (P = .011, Figure 1), compared with patients with short prepandemic MI. This is consistent with the current recommendations2 , 3 that the time interval between VIT injections may be extended, but this should be done progressively over years, after reaching the maintenance dose, especially for VIT efficacy. Moreover, limited data are available on the efficacy and safety of time intervals longer than 12 weeks,9 , 10 and fast and long extensions are not recommended in patients who have started VIT recently and/or who have still short intervals (eg, <4 weeks).

This is supported by the SRs that occurred in the patient with the shortest VIT duration (1 month) and prepandemic MI (2 weeks) of our study population (Table IV, patient 1). A fast and long extension has been required because of the pandemic (delay, 10 weeks) in this patient, but it was not tolerated.

The severity of the pre-VIT reaction to Hymenoptera stings was another baseline characteristic significantly correlated with the delay (P = .001; Figure 2, A), and to the subsequent new postpandemic MI (P = .047). Indeed, the applied interval extension was shorter, in case of severe baseline reactions, even though currently they are not regarded as risk factors for SRs.2

Concerning duration of VIT, the allowed delay between injections was shorter in the patients who had been undergoing VIT for many years, compared with the ones who had started VIT more recently, but this correlation was not linear (P = .085). The SRs experienced by the patient with the shortest VIT duration (patient 1 was the only one undergoing VIT for just 1 month) seems to confirm this risk factor in a nonlinear way, meaning that there may be risk in delaying too much the VIT administrations shortly after starting VIT (ie, recent VIT initiation ≤1 month), but afterwards the risk does not increase linearly with the VIT duration in our study.

Age was another factor considered for the extension, which was shorter in patients 65 years or older, compared with the younger patients (P = .017; Figure 2, B). However, all the 3 patients who experienced SRs were quite young (<44 years old).

Overall, comorbidities did not play a crucial role in deciding the new intervals, because all our patients had well-controlled diseases. However, more caution was paid in case of multidrug treatments. Consequently, our results do not show a significant relationship between delay and comorbidities, but the delay was significantly shorter for patients undergoing concomitant treatments (P = .041).

However, the sex, type of HVA, comorbidities, the prepandemic threshold of skin reactivity, previous SEs related to VIT, diagnosed mastocytosis or potential mast cell disorders (ie, abnormal REMA score), and high STLs were not correlated with the VIT delay, because these factors were not considered limiting factors to extend the intervals, according to our clinical decision making. In fact, the extension of the time intervals (ie, a mean delay of 8.5 weeks, leading to new postpandemic MI in the range of 8-22 weeks) in our population was totally tolerated even in case of comorbidities (including 43% of patients with cardiovascular diseases and 5% with mastocytosis), high skin test reactivity (29% of patients positive at ≤0.01 μg/mL), history of previous reactions during VIT injections (9%), high STLs (10%), and abnormal REMA score (29%).

However, notwithstanding that the low number of SRs hinders a proper analysis of risk factors, it is noteworthy that all the 3 patients with SRs share the bee venom allergy as a statistically significant risk factor (P = .002). This finding underlines the well-known peculiarity of bee venom.

In fact, bee venom allergy has been associated with lower efficacy and higher incidence of SRs to VIT compared with Vespula venoms.13 The gradual lengthening of the MI up to 12 weeks does not appear to interfere with either efficacy or safety of VIT,2 , 3 but it has been documented mainly for vespid VIT. And only 1 study showed that further prolonging the MI up to 6 months reduces VIT efficacy using bee venom extract while preserving its safety.9 Thus, more studies are needed to safely extend the MI or to resume VIT after long delay in patients with allergy to bee venom, not only in those who have recently started the treatment but also in long-term VIT.

To date, this is the first study providing practical recommendations on the management of VIT during a pandemic, based on the real-life experience with a considerable sample size. The lessons may be applicable in clinical practice not only in case of pandemics but also whenever any delay in VIT administration is necessary because of other causes (eg, patients' needs). According to our experience, attention should be paid in extending the time intervals between injections in case of already long MI, severe pre-VIT reaction, older age, and/or multidrug concomitant treatments. In addition, our results suggest that bee venom allergy and recent initiation of VIT should be considered before extending VIT intervals, because they may be the possible culprits of the SEs observed in this study, whereas a diagnosed or very likely (according to REMA score) mast cell disease does not seem to be a risk factor for prolonging VIT MI.

Finally, some limitations must be pointed out in our study. First, the low number of SRs is a clinical success and demonstrated the high safety profile of extending the VIT MI in our population, but it makes the association between SEs and the identified risk factors (ie, bee venom) less robust, from a statistical point of view. Second, data come from a single center in Europe where the approach is likely to be different from that in the United States (ie, by type of induction phase or extracts used). Therefore, additional studies would be needed to confirm our results.

Conclusions

Learning from the COVID-19 emergency, this study suggests a safe and effective protocol to resume VIT after a long, unplanned, and unavoidable delay in treatment. A new build-up phase may be safely avoided in most cases, with advantages in terms of patients' compliance and VIT-related costs.

Our patients are representative of a real-life population with the most common characteristics of patients with HVA in terms of demographic, allergy and VIT characteristics, and concomitant conditions (Table I). In this population, resuming VIT after a delay in treatment was generally safe and well tolerated. More caution should be paid in resuming VIT in case of long prepandemic MI, severe pre-VIT reaction, recent VIT initiation, older age, multidrug treatments, and bee venom allergy. Experienced staff, well-trained in HVA, is always recommended.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bilò M.B., Pravettoni V., Bignardi D., Bonadonna P., Mauro M., Novembre E. Hymenoptera venom allergy: management of children and adults in clinical practice. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2019;29:180–205. doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturm G.J., Varga E.M., Roberts G., Mosbech H., Bilò M.B., Akdis C.A. EAACI guidelines on allergen immunotherapy: Hymenoptera venom allergy. Allergy. 2018;73:744–764. doi: 10.1111/all.13262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golden D.B.K., Demain J., Freeman T., Graft D., Tankersley M., Tracy J. Stinging insect hypersensitivity. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;118:28–54. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilò M.B., Pravettoni V., Mauro M., Bonadonna P. Treating venom allergy during COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print July 16, 2020] Allergy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Klimek L., Jutel M., Akdis C., Bousquet J., Akdis M., Bachert C. Handling of allergen immunotherapy in the COVID-19 pandemic: an ARIA-EAACI statement. Allergy. 2020;75:1546–1554. doi: 10.1111/all.14336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Codispoti C.D., Bandi S., Moy J.N., Mahdavinia M. Running a virtual allergy division and training program in the time of COVID-19 pandemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:1357–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaker M.S., Oppenheimer J., Grayson M., Stukus D., Hartog N., Hsieh E.W.Y. COVID-19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1477–1488.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez-Twose I., González-de-Olano D., Sánchez-Muñoz L., Matito A., Jara-Acevedo M., Teodosio C. Validation of the REMA score for predicting mast cell clonality and systemic mastocytosis in patients with systemic mast cell activation symptoms. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;157:275–280. doi: 10.1159/000329856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg A., Confino-Cohen R. Effectiveness of maintenance bee venom immunotherapy administered at 6-month intervals. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:352–357. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baenkler H.W., Meußer-Storm S., Eger G. Continuous immunotherapy for hymenoptera venom allergy using six month intervals. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2005;33:7–14. doi: 10.1157/13070602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilò M.B., Kamberi E., Tontini C., Marinangeli L., Cognigni M., Brianzoni M.F. High adherence to hymenoptera venom subcutaneous immunotherapy over a 5-year follow-up: a real-life experience. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:327–329.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilò M.B., Antonicelli L., Bonifazi F. Purified vs. nonpurified venom immunotherapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;10:330–336. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328339f2d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Müller U., Helbling A., Berchtold E. Immunotherapy with honeybee venom and yellow jacket venom is different regarding efficacy and safety. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;89:529–535. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90319-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]