Abstract

Aim: This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cerebrovascular disease (CeVD) events in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Methods: We searched the literatures in Pubmed, Embase, and Web of Science to identify cohort studies reporting the association between PCOS and CVD/CeVD events from 1964 to June 1, 2020. Outcome variables, such as all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, any cardiovascular diseases, myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and stroke, were extracted from the identified literatures, and we reported the outcomes of the association in hazard ratios (HR) and odds ratios (OR).

Results: Ten cohort studies comprising 166,682 samples are included in the review. Compared to non-PCOS women, the pooled risk of CVD events in PCOS women (OR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.32–2.08). In addition, the risk of myocardial infarction (OR: 2.57, 95% CI: 1.37–4.82), ischemic heart disease (OR: 2.77, 95% CI: 2.12–3.61), and stroke (OR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.56–2.47) are higher in the PCOS group. However, no significant difference in the overall mortality (HR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.57–1.86) and CVD-related death (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 0.99–2.23) was observed. Funnel plots of all outcomes are roughly symmetric, and no significant publication bias was found.

Conclusion: Though this study identified an increased risk of CVD and CeVD among women with PCOS, including occurrence of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and stroke, there was no difference in the all-cause or CVD-related mortality observed. Further large-scale studies are warranted to strengthen the association between PCOS and CV events. Our study may require a larger sample size to further verify the conclusions.

Keywords: polycystic ovary syndrome, cardiovascular disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, mortality

Background

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disease, which shows common polymorphic and clinical manifestations and 5–10% of morbidity in women of reproductive age (1, 2). It is caused by follicular dysplasia, insulin resistance (IR), and hyperandrogenism, which is characterized by irregular menstruation, infertility, obesity, and hyperandrogenemia (3, 4). PCOS patients often experience metabolic disturbances, which are easily combined with lipid metabolism disorders, obesity hypertension, diabetes, and other metabolic synthesis (5). Thus, PCOS patients have increased risk of atherosclerosis, which thereby significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) (5).

CVDs are the number one cause of death globally, taking an estimated 17.9 million lives each year. CVDs are a group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels and include coronary heart disease (CHD), cerebrovascular disease (CeVD), rheumatic heart disease, and other conditions. Four out of five CVD deaths are due to heart attacks and strokes, and one third of these deaths occur prematurely in people under 70 years of age (6). PCOS patients are often associated with obesity; most patients show a tendency to be obese during or even before puberty, and obesity is a risk factor of CVD, which thereby increases its incidence (7). Abnormal lipid metabolism often exists in PCOS patients with an approximately 70% prevalence rate, and it is mainly manifested as high-density lipoprotein (HDL) decrease and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) increase (8). At present, there are various studies on the risk of PCOS and CVD, but the results differ. Meta-analyses (9, 10) suggest that PCOS patients have a higher risk of CVD than normal people. In the study published in 2016, the results showed that a significant association was found between PCOS and CHD, no significant association was observed between PCOS and myocardial infarction (MI). In an article published in 2017, compared with those without PCOS, subjects with PCOS were significantly associated with an increased risk of developing stroke. However, no significant association was observed between PCOS and all-cause death in that article. In addition, a review of longitudinal studies (11) on the increased CVD prevalence is not proven. Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to better clarify the relationship between the PCOS and the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events and mortality.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

Our search used the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Meta-analysis. We obtained a list of eligible studies from the following databases: PubMed, EMBase, and Web of Science, published in English up to June 1, 2020. The search MESH term and keywords used included “polycystic ovary syndrome,” “PCOS,” “Stein-Leventhal syndrome,” “sclerocystic ovarian degeneration,” “cardiovascular diseases,” “coronary heart disease,” “myocardial infarction,” “cardiovascular stroke,” “myocardial infarct,” “heart attack,” “ischemic heart disease,” “myocardial ischemia,” “stroke,” “cerebrovascular accident,” and “apoplexy.” Detailed search strategies are shown in Supplementary Method 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were (1) exposed group was defined as PCOS according to the PCOS diagnostic criteria. Diagnosis of PCOS was classified as definite and possible PCOS. Definite PCOS was defined as histological evidence with clinical evidence of ovarian dysfunction. Possible PCOS was defined as histological evidence with clinical information not available, macroscopic evidence with clinical evidence of ovarian dysfunction, or clinical diagnosis by an experienced consultant (12). (2) The non-exposed group was defined as those without PCOS disease. (3) Cardiovascular outcomes included subclinical and clinical cardiovascular disease prevalence, incidence, and mortality. The outcomes were defined as mortality rate, which includes all-cause mortality and cardiovascular death, and cardiovascular event incidence, including any CVD, MI, ischemic heart disease, and stroke. Cardiovascular death was defined as that resulting from sudden cardiac death, end-stage congestive heart failure, acute MI, peripheral arterial disease, or cerebrovascular accident. (4) The study design was cohort studies only, and the language of the included stuies was limited to English.

The exclusion criteria for this study were (1) the patient had a prior cardiovascular event; (2) the study was a conference, abstract, or letter; (3) republished studies; (4) outcome data of study were unavailable.

Data Collection and Quality Assessment

Relative data were extracted by two independent authors (JZ and CG) with a unified standard. Differences or contradictions between the authors were resolved by discussion or consultation of a third investigator (GQZ). We extracted relevant information from the included studies, such as (1) basic characteristics of individual study: first author, published year, country, mean age, sample, study design, race, PCOS diagnosis, control group, adjustment factors, and follow-up; (2) clinical physiological and biochemical characteristics of individual study: BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, smoking rate, postmenopausal women, systolic, diastolic, hypertension, diabetes, IR, HOMA dyslipidemia, total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, androstenedione, testosterone, free testosterone, and fasting glucose; (3) outcomes: all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, any CVD, MI, ischemic heart disease, and stroke. In the original literature, if there is original data, the data on the original event is extracted; if not, the combined effect quantity is extracted. If multiple effect estimates are reported, we use the most comprehensive adjusted risk estimates.

Methodological quality of the studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) with eight items. A study can be rewarded a maximum of nine stars with a maximum of two stars for comparability and one star for each numbered item within the selection and exposure categories. More than six stars indicates a study of high quality.

Statistical Analysis

The effect size of hazard ratio (HR) (13) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used for the outcome of mortality rate, and the odds ratios (OR) (14, 15) with 95% CI was used for the incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. The I2 statistical value using chi-square tests was used to evaluate and measure the heterogeneity size (16). When the I2 value was >40% with significance level of P < 0.1, heterogeneity was identified in relevant outcome. Funnel plots were used to qualitatively detect publication bias (17). Statistical analyses of all outcomes were performed using RevMan software (Versions 5.3).

Result

Literature Search Results

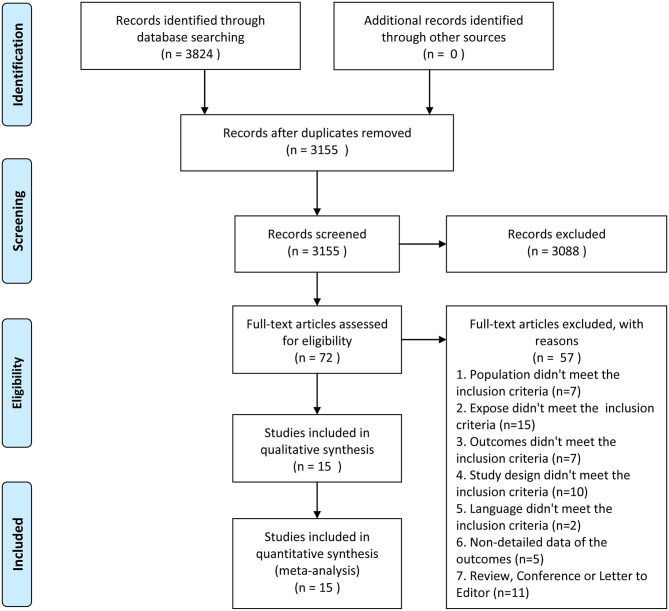

Initially, 3,824 literatures were identified from PubMed, EMBase, and Web of Science. However, 669 of those were excluded due to duplication, 3,088 studies were excluded by reading titles and abstracts based on the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 72 potential studies were screened for full-text reading. Finally, 15 cohort studies with 352,031 individuals (18–32) were chosen (Figure 1). Average follow-up duration ranged from 5 to 22 years. Patients were followed up for an average of more than 10 years in a majority of studies (73.3%). Ten of the articles' risk estimates

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of selection process.

were adjusted for age and BMI. Ten studies (66.7%) reported an adjusted estimate for at least one of the risk factors. The basic characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1, and the clinical physiological and biochemical characteristics of individual studies are provided in Table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of individual studies.

| Study | Year | Country | Age | Sample | Race | Diagnosis of PCOS | Source of control | Adjustment factors | Follow-up (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calderon-Margalit | 2014 | USA | 45.4(3.44); 45.4 (3.57) | 55/668 | Black 376, White 374 | NR | Women who had none of these symptoms | Age, Race, Education, Smoking, Menopausal Status, BMI, SBP, lnTG, and HOMA-IR | 20 |

| Dahlgren | 1992 | Sweden | 45.9(40-49); 55.1(50–61) | 40–49 Y: 18/57; 50–61 Y: 15/75 | NR | Histopathological characteristics | Age matched referents | NR | 12 |

| Ding | 2018 | Taiwan | 15–49 | 8,048/32,192 | NR | ICD-9 | NR | NR | 16 |

| Glintborg | 2015 | Denmark | 29(23–35) | 77,899 | NR | ICD-10 | The index date of their matched PCOS cases | NR | 17 |

| Hart | 2015 | Australia | NR | 2,560/26,660 | NR | ICD-10 or ICD-9 | Hospital population | Any potential effect of PCOS on hospitalizations related to adult onset diabetes | 15 |

| Iftikhar | 2012 | USA | 25.0 ± 5.3 | 309/652 | NR | ICD | Matched age and calendar year during their clinic visit plus three years | Age at last follow-up, BMI, infertility treatment, postmenopausal hormone therapy, and family history. | 22 |

| Joan | 2006 | USA | 30.7 ± 7.2/30.8 ± 7.5 | 11,035/55,175 | White 1,209/3,778, Black 226/522, Asian 288/1,117, Hispanic 352/1,324, Other 140/432 | ICD-9 | Health plan membership | Hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and BMI | NR |

| Lunde | 2007 | Norway | 49.8(42.8, 57.4)/46.6(35.6, 57.2) | 131/854 | NR | Ultrasound examination and histological examination | Matched age, birth cohort and observation time | NR | 15–20 |

| Mani | 2013 | UK | 29.6 ± 9.1 | 2,301 | White 1,479, South Asian 677, Black 26, Other 119 | Clinical and biochemical grounds | National Female Population | BMI, age and hypertension | 20 |

| Merz | 2016 | USA | 62.6 ± 11.6/64.8 ± 9.6 | 25/270 | NR | 1990 NIH criteria, 2003 European and American criteria | Registered menopausal population in the WISE | Diabetes, waist circumference, hypertension, and angiographic CAD | 10 |

| Morgan | 2012 | UK | 27.1 ± 7.1/27.1 ± 7.1 | 21,734/108,670 | NR | NR | Matched primary-care practice, age and BMI | Age, primary-care contacts, BMI, and year of diagnosis | 5 |

| Meun | 2018 | Netherlands | 69.57 ± 8.72/69.20 ± 8.60 | 106/171 | NR | NR | NR | Age, years since menopause and cohort | 12 |

| Schmidt | 2011 | Sweden | NR | 32/127 | Caucasian | Rotterdam criteria | Age-matched control | NR | 21 |

| Shaw | 2008 | UA | 62.5 ± 10/65.8 ± 9 | 104/390 | NR | NR | Women without clinical features of PCOS from NIH-NHLBI | Age and body mass index | 6 |

| Wild | 2000 | UK | NR | 319/1,379 | NR | Histopathology records, operating theater records, admission and discharge records and diagnostic indexes | Age matched referents | BMI | 5 |

BMI, body mass index; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; NR, Not reported; PCOS, Polycystic ovary syndrome.

Table 2.

Clinical physiological and biochemical characteristics of individual studies.

| Study | Year | BMI | Wraist to hip ratio | Smoking rate | Post-menopausal women | Systolic (mmHg) | Diastolic (mmHg) | Hypertension | Diabetes | Fasting glucose (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calderon-Margalit | 2014 | 29.3 (6.50);29.9 (7.47) | NR | 23/287 | 7/153 | 113 ± 15.9/115 ± 16.3 | 71.6 ± 11.8/72.7 ± 11.7 | 10/118 | 4/36 | 100 ± 36.3/95.4 ± 22.4 |

| Dahlgren | 1992 | NR | 40–49 Y: 0.81 ± 0.06/0.78 ± 0.06; 50–61 Y: 0.84 ± 0.09/0.79 ± 0.07 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 40–49 Y: 18/75; 50–61 Y: 15/90 | 40–49Y: 18/75; 50–61 Y: 15/90 | NR |

| Ding | 2018 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Glintborg | 2015 | 27.3(23–32.7) | NR | 51/82 | NR | NR | NR | 357/365 | 458/423 | 4.6(4.3–5.0) |

| Hart | 2015 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Iftikhar | 2012 | 29.4 ± 7.77/28.3 ± 7.47 | NR | 80/652 | 652/652 | NR | NR | 80/309;73/343 | NR | 94(39–338)/94(68–208) |

| Joan | 2006 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Lunde | 2007 | 24.7(17,36.9) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11 | 6 | NR |

| Mani | 2013 | 30.1 ± 7.6 | NR | 311/2,301 | NR | 130.5 ± 15.7 | 73.7 ± 11.1 | NR | 88/2,301 | NR |

| Merz | 2016 | 28.7 ± 5.9/30.0 ± 6.7 | NR | 9/46 | All | 141.4 ± 19.9/140.4 ± 21.6 | 75.4 ± 12.5/76.7 ± 10.9 | 12/171 | 6/87 | 109.78 ± 46.5/121.4 ± 60.5 |

| Morgan | 2012 | 28.7 ± 8.2/25.5 ± 5.8 | NR | 28,103/108670 | NR | 119.4 ± 14.3/116.8 ± 13.1 | 75.2 ± 14.3/72.5 ± 13.1 | NR | 713/21,734; 966/86,936 | NR |

| Meun | 2018 | 27.92 ± 4.53/26.84 ± 3.83 | 0.89 ± 0.08/0.86 ± 0.08 | 17/28 | NR | 142.3 ± 21.74/143.61 ± 19.22 | 74.55 ± 10.39/77.03 ± 9.92 | 70/107 | 20/12 | 6.25 ± 1.83/5.79 ± 1.41 |

| Schmidt | 2011 | NR | NR | 15/93 | 127/127 | 139.4 ± 20.2/123.1 ± 14.9 | 82.7 ± 10.6/79.1 ± 6.6 | NR | NR | NR |

| Shaw | 2008 | 31.1 ± 7/28.4 ± 6 | 0.885 ± 0.12/0.857 ± 0.11 | 27/45 | 390/390 | 139.9 ± 20/140.1 ± 22 | 77.4 ± 10/75.7 ± 11 | 63/104;126/286 | 34/104;70/286 | 132.1 ± 67/126.1 ± 58 |

| Wild | 2000 | 26.6/25.9 | 0.82/0.72 | 40/232 | P/C:81/82 | 132/132 | 79/82 | 273/1,379 | 54/1,379 | NR |

| Study | Year | Insulin resistance, HOMA | Dyslipidemia | Total cholesterol | LDL cholesterol | HDL cholesterol | Triglycerides (mm/L) | Androstenedione (nmol/L) | Testosterone (mmol/L) | Free testosterone |

| Calderon-Margalit | 2014 | 5.32 ± 9.13/3.86 ± 2.96 | 8/48 | 4.90 ± 0.79/4.77 ± 0.87 | 2.79 ± 0.78/2.76 ± 0.76 | 1.55 ± 0.46/1.52 ± 0.41 | 1.22 ± 0.96/1.08 ± 0.79 | NR | NR | NR |

| Dahlgren | 1992 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 40–49 Y: 1.16 ± 0.58/1.21 ± 0.52; 50–61 Y: 1.58 ± 0.92/1.35 ± 0.61 | NR | NR | NR |

| Ding | 2018 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Glintborg | 2015 | 12.2(8.1–20.1) | 112/108 | 1.0(0.7–1.5) | 2.7(2.2–3.3) | 1.4(1.1–1.6) | NR | NR | 1.74(1.24–2.38) | 0.033(0.021–0.050) |

| Hart | 2015 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Iftikhar | 2012 | NR | MA | 197(92–330)/199(0–369) mg/dl | 108(26–225)/111(38–211) mg/dl | 57(23–106)/58(23–129) mg/dl | 107(29–473)/110 (33–431) | NR | NR | NR |

| Joan | 2006 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Lunde | 2007 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Mani | 2013 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Merz | 2016 | 3.07 ± 5.02/5.35 ± 8.24 | 16/146 | 195.3 ± 36.6/197.8 ± 48.5 mg/dl | 110.1 ± 29.4/116.2 ± 42.0 mg/dl | 47.9 ± 10.3/52.5 ± 11.2 mg/dl | NR | 0.4 | 0.83 | 0.55 |

| Morgan | 2012 | NR | NR | 4.9 ± 1.0/4.9 ± 1.0 mmol/L | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Meun | 2018 | NR | NR | 5.98 ± 0.85/6.09 ± 1.01 | NR | 1.40 ± 0.35/1.57 ± 0.39 | NR | 2.63(2.00–3.31)/2.17(1.67–2.88) | 1.30(1.04–1.71)/0.74(0.68–0.80) | 2.69(2.13–3.49)/1.16(1.05–1.29) |

| Schmidt | 2011 | NR | MA | 5.9 ± 0.8/5.9 ± 1.1 mmol/L | 2.2 ± 0.7/2.7 ± 0.8 mmol/L | 2.0 ± 0.4/1.6 ± 0.3 mmol/L | 1.4 ± 0.7/1.0 ± 0.5 | NR | NR | NR |

| Shaw | 2008 | 35/104;63/286 | NR | 203.7 ± 49/194.4 ± 46 mg/dl | 120.2 ± 41/114.4 ± 42 mg/dl | 50.8 ± 12/52.4 ± 11 mg/dl | 184.3 ± 147/147.0 ± 113 | NR | NR | NR |

| Wild | 2000 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

BMI, body mass index; NR, Not reported.

Results of Mate Analysis

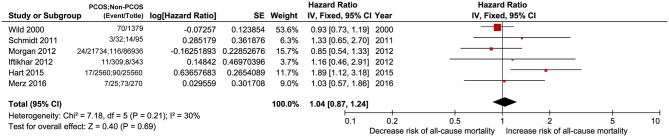

All-Cause Mortality

Six studies including PCOS and non-PCOS were involved in the outcome of all-cause mortality evaluation. Compared with patients in the non-PCOS group, patients in the PCOS group had no significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.57–1.86, P = 0.69; I2 = 30%, P = 0.21) in a fixed-effects model (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing PCOS and non-PCOS for all-cause mortality.

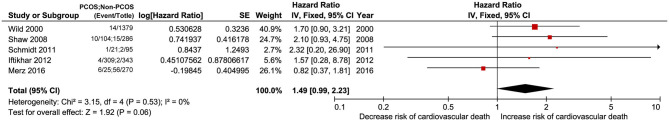

Cardiovascular Death

Five studies including PCOS and non-PCOS were involved in the outcome of cardiovascular death evaluation. Compared with patients in the non-PCOS group, patients in the PCOS group had no significantly increased risk of cardiovascular death (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 0.99–2.23, P = 0.06; I2 = 0%, P = 0.53) in a fixed-effects model (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing PCOS and non-PCOS for cardiovascular death.

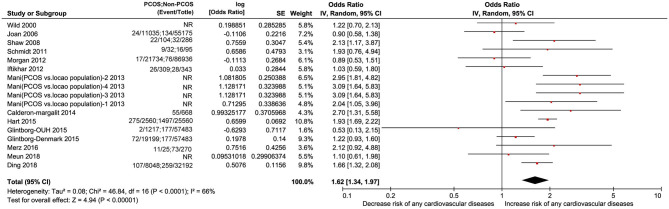

Any CVD

Seventeen studies including PCOS and non-PCOS were involved in the outcome of any CVD evaluation. Compared with patients in the non-PCOS group, patients in the PCOS group had significantly increased risk of CVD (OR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.32–2.08, P < 0.00001; I2 = 66%, P < 0.0001) in a random-effects model (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot comparing PCOS and non-PCOS for any CVDs. NR, not reported.

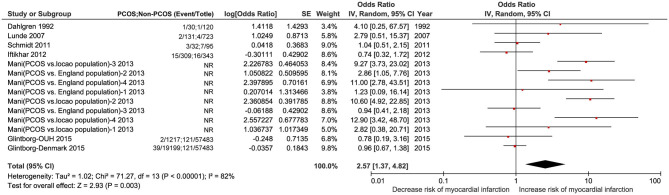

MI

Fourteen studies including PCOS and non-PCOS were involved in the outcome of MI evaluation. Compared with patients in the non-PCOS group, patients in the PCOS group had significantly increased risk of MI (OR: 2.57, 95% CI: 1.37–4.82, P = 0.003; I2 = 82%, P < 0.00001) in a random-effects model (Figure 5). There was larger heterogeneity in this subgroup analysis using the random effects model.

Figure 5.

Forest plot comparing PCOS and non-PCOS for MI. NR, not reported.

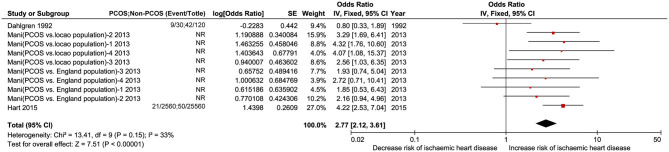

Ischemic Heart Disease

Ten studies including PCOS and non-PCOS were involved in the outcomes of ischemic heart disease evaluation. Compared with patients in the non-PCOS group, patients in the PCOS group had significantly increased risk of ischemic heart disease (OR: 2.77, 95% CI: 2.12–3.61, P < 0.00001; I2 = 33%, P = 0.15) in a fixed-effects model (Figure 6). No heterogeneity was found in this subgroup analysis.

Figure 6.

Forest plot comparing PCOS and non-PCOS for ischemic heart disease. NR, not reported.

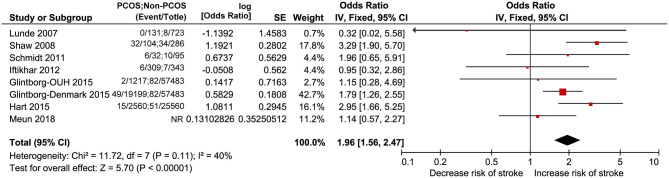

Stroke

Eight studies including PCOS and non-PCOS were involved in the outcome of stroke evaluation. Compared with patients in the non-PCOS group, patients in the PCOS group had significantly increased risk of stroke (OR: 1.96, 95% CI: 1.56–2.47, P < 0.00001; I2 = 40%, P = 0.11) in a fixed-effects model (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Forest plot comparing PCOS and non-PCOS for stroke.

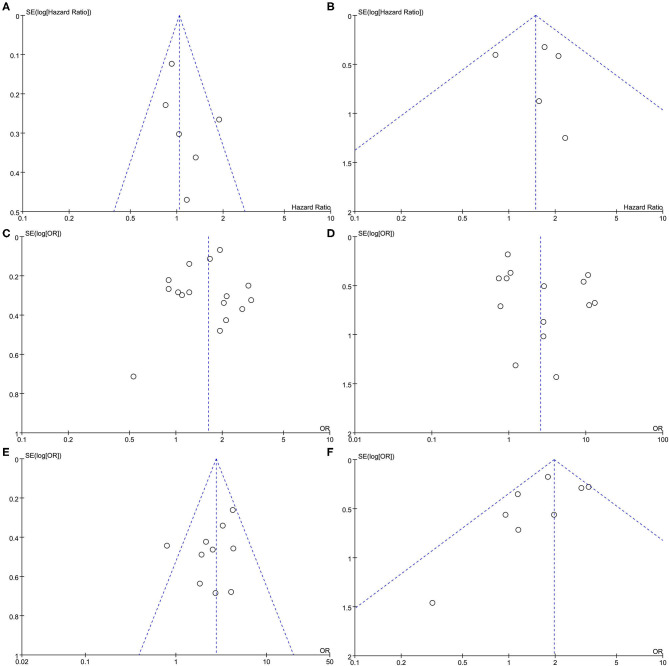

Publication Bias

Funnel plots were performed for all outcomes presented in Figures 8A–F. Funnel plots of all outcomes were roughly symmetric, and no significant publication bias was found.

Figure 8.

Funnel plot comparing PCOS and non-PCOS in all outcomes. (A) All cause morality. (B) Cardiovascular death. (C) Any cardiovascular diseases. (D) Myocardial infarction. (E) Ischemic heart diseases. (F) Stroke.

Discussion

A large amount of data in this meta-analysis shows that PCOS and non-PCOS significantly differ in the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, including any CVDs, MI, ischemic heart disease, and stroke, which indicates the relationship between PCOS and CVD risk. However, it did not lead to an increase in the associated mortality rate. To this day, the common pathophysiologic mechanisms are also unclear and require further study (8, 11).

In recent years, PCOS prevalence has gradually increased, and the clinical mechanism of its metabolism has received much attention (1, 33). Metabolic syndrome is a group of clinical syndromes characterized by the accumulation of various heart and cerebral risk factors, including hyperinsulinemia, IR causing obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, and it directly promotes the atherosclerosis course, wherein CVD and CeVD are the main clinical consequences (34). PCOS prevalence is on the rise, which may be related to genetic factors, dyslipidemia, and hypertension combined with excessive androgen, which may explain the increased risk factor of CVD in patients with PCOS (18, 27, 35). The relative risk of MI in PCOS women increases four times between the ages of 40 and 49 and 11 times between the ages of 50 and 60 (36, 37). On the basis of a report from the American Heart Association in 2019 (38), accounting for 31% of the total number of deaths from CVD, it has become a common and frequently occurring disease that seriously affects human quality of life.

IR and hyperinsulinemia are common in PCOS (39). IR can induce and enhance oxidative stress, affect vascular endothelial function, cause vascular endothelial injury and decreased vascular compliance, and promote CVD progress (40). Changes in intrinsic risk mechanisms, including increased LDL and TG synthesis, enhanced gluconeogenics, decreased lipoprotein lipase activity, decreased liver clearance of LDL and TG, and abnormal lipid metabolism production, lead to obesity in the PCOS population (41). PCOS causes the liver to secrete LDL, and the conversion of cholesterol from HDL to LDL accelerates. HDL reduces and increases the risk of atherosclerosis, dyslipidemia (42). Moreover, PCOS patient's metabolic disturbances also cause hypertension that mainly changes vascular function as caused by hyperinsulinemia (43). High insulin levels enable increased NA+ reabsorption of the kidneys, increases aldosterone secretion, and decreases prostacyclin synthesis and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation (44). Further, inflammatory cytokines and leptin levels were increased due to excessive fat accumulation, which leads to IR and induction of sympathetic nerve excitement, leading to hypertension (45).

The risk factors for CVD are complex, such as hypertension, smoke, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic synthesis character (38). There is still no obvious effective treatment for PCOS at present, and the focus is still on preventing complications, especially the occurrence and development of cardiovascular-related events (46). Further research is needed to improve the diagnostic process with aims to select specific treatment, customizing the therapy and lifestyle modifications (46).

This study has some advantages. First of all, this meta-analysis shows that PCOS can increase the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, including any CVDs, MI, ischemic heart disease, and stroke, but the mortality-related outcomes cannot. Second, compared with previous studies, our conclusions are basically consistent with the research opinions of other meta-analyses (9, 10) on risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, but there were differences in mortality outcomes. The results of the previous two studies were not only relatively simple, but also not statistically significant in other studies. In addition, compared with previous research results, the results of this paper are more comprehensive and include a larger study population, which makes the research results more convincing and provides readers with more comprehensive information. In the end, the inclusion results of this paper are consistent with the expected analysis results, which provide some treatment ideas and medication plans for the diagnosis and treatment of clinical departments.

However, the limitations should also be considered in this study. At first, the occurrence and development of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in PCOS individuals are related to many factors, especially a series of physiological and biochemical indicators, such as BMI, blood glucose, and blood lipids. However, the original study did not provide too much relevant data for further analysis. This study cannot perform subgroup analysis and meta-regression to explore and resolve clinical heterogeneity issues caused by these significantly related factors.

This study demonstrates that women with PCOS have increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, including any CVDs, MI, ischemic heart disease, and stroke but not mortality-related outcomes. Clinicians should provide timely, effective, and personalized interventions to prevent or delay the occurrence and development of related reinsurance to improve the quality of life of patients with PCOS. Our study may require a larger sample size to further verify the conclusions.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

This study was designed by J-HX. JZ and Q-QQ contributed data to the paper. Statistical analysis and interpretation of data were performed by J-HX, JZ and G-QZ. All authors were involved in drafting and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version to be published.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcvm.2020.552421/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Azziz R, Woods KS, Reyna R, Key TJ, Knochenhauer ES, Yildiz BO. The prevalence and features of the polycystic ovary syndrome in an unselected population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2004) 89:2745–9. 10.1210/jc.2003-032046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clayton RN, Ogden V, Hodgkinson J, Worswick L, Rodin DA, Dyer S, et al. How common are polycystic ovaries in normal women and what is their significance for the fertility of the population? Clin Endocrinol. (1992) 37:127–34. 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cibula D, Cifkova R, Fanta M, Poledne R, Zivny J, Skibova J. Increased risk of non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension and coronary artery disease in perimenopausal women with a history of the polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. (2000) 15:785–9. 10.1093/humrep/15.4.785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinoshita T, Kato J. Impaired glucose tolerance in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Horm Res. (1990) 33(Suppl 2):18–20. 10.1159/000181560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedaiwy MA, Abdel-Rahman MY, Tan J, AbdelHafez FF, Abdelkareem AO, Henry D, et al. Clinical, hormonal, and metabolic parameters in women with subclinical hypothyroidism and polycystic ovary syndrome: a cross-sectional study. J Women's Health. (2018) 27:659–64. 10.1089/jwh.2017.6584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO) . Cardiovascular Diseases. (2019). Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases.

- 7.Vatopoulou A, Tziomalos K. Management of obesity in adolescents with polycystic ovary syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother. (2020) 21:1–5. 10.1080/14656566.2019.1701655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang Y, Qi J., Xue X., Huang R., Zheng J., Liu W., et al. Ceramide subclasses identified as novel lipid biomarker elevated in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot study employing shotgun lipidomics. Gynecol Endocrinol. (2019) 36:1–5. 10.1080/09513590.2019.1698026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao L, Zhu Z, Lou H, Zhu G, Huang W, Zhang S, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD): a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:33715–21. 10.18632/oncotarget.9553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y, Wang X, Jiang Y, Ma H, Chen L, Lai C, et al. Association between polycystic ovary syndrome and the risk of stroke and all-cause mortality: insights from a meta-analysis. Gynecol Endocrinol. (2017) 33:904–10. 10.1080/09513590.2017.1347779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacewicz-Swiecka M, Kowalska I. Polycystic ovary syndrome and the risk of cardiometabolic complications in longitudinal studies. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. (2018) 34:e3054. 10.1002/dmrr.3054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Group . R. E. A.-S. P. C. W. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. (2004) 81:19–25. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J. Semiparametric hazard function estimation in meta-analysis for time to event data. Res Synth Methods. (2012) 3:240–9. 10.1002/jrsm.1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deeks JJ. Issues in the selection of a summary statistic for meta-analysis of clinical trials with binary outcomes. Stat Med. (2002) 21:1575–600. 10.1002/sim.1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenland S. Interpretation and choice of effect measures in epidemiologic analyses. Am J Epidemiol. (1987) 125:761–8. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson SG, Sharp SJ. Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med. (1999) 18:2693–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copas J, Shi JQ. Meta-analysis, funnel plots and sensitivity analysis. Biostatistics. (2000) 1:247–62. 10.1093/biostatistics/1.3.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calderon-Margalit R, Siscovick D, Merkin SS, Wang E, Daviglus ML, Schreiner PJ, et al. Prospective association of polycystic ovary syndrome with coronary artery calcification and carotid-intima-media thickness: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Women's study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2014) 34:2688–94. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dahlgren E, Janson PO, Johansson S, Lapidus L, Oden A. Polycystic ovary syndrome and risk for myocardial infarction. Evaluated from a risk factor model based on a prospective population study of women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. (1992) 71:599–604. 10.3109/00016349209006227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding DC, Tsai IJ, Wang JH, Lin SZ, Sung FC. Coronary artery disease risk in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Oncotarget. (2018) 9:8756–64. 10.18632/oncotarget.23985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glintborg D, Hass Rubin K, Nybo M, Abrahamsen B, Andersen M. Morbidity and medicine prescriptions in a nationwide Danish population of patients diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. (2015) 172:627–38. 10.1530/EJE-14-1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart R, Doherty DA. The potential implications of a PCOS diagnosis on a woman's long-term health using data linkage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2015) 100:911–9. 10.1210/jc.2014-3886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iftikhar S, Collazo-Clavell ML, Roger VL, St Sauver J, Brown RD, Jr, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Neth J Med. (2012) 70:74–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo JC, Feigenbaum SL, Yang J, Pressman AR, Selby JV, Go AS. Epidemiology and adverse cardiovascular risk profile of diagnosed polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2006) 91:1357–63. 10.1210/jc.2005-2430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lunde O, Tanbo T. Polycystic ovary syndrome: a follow-up study on diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and malignancy 15–25 years after ovarian wedge resection. Gynecol Endocrinol. (2007) 23:704–9. 10.1080/09513590701705189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mani H, Levy MJ, Davies MJ, Morris DH, Gray LJ, Bankart J, et al. Diabetes and cardiovascular events in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a 20-year retrospective cohort study. Clin Endocrinol. (2013) 78:926–34. 10.1111/cen.12068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merz CN, Shaw LJ, Azziz R, Stanczyk FZ, Sopko G, Braunstein GD, et al. Cardiovascular disease and 10-year mortality in postmenopausal women with clinical features of polycystic ovary syndrome. J Women's Health. (2016) 25:875–81. 10.1089/jwh.2015.5441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meun C, Franco OH, Dhana K, Jaspers L, Muka T, Louwers Y, et al. High androgens in postmenopausal women and the risk for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease: the rotterdam study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2018) 103:1622–30. 10.1210/jc.2017-02421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan CL, Jenkins-Jones S, Currie CJ, Rees DA. Evaluation of adverse outcome in young women with polycystic ovary syndrome versus matched, reference controls: a retrospective, observational study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2012) 97:3251–60. 10.1210/jc.2012-1690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt J, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Brannstrom M, Dahlgren E. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in PCOS women of postmenopausal age: a 21-year controlled follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2011) 96:3794–803. 10.1210/jc.2011-1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw LJ, Bairey Merz N, Azziz R, Stanczyk FZ, Sopko G, Braunstein GD, et al. Postmenopausal women with a history of irregular menses and elevated androgen measurements at high risk for worsening cardiovascular event-free survival: results from the National Institutes of Health—National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2008) 93:1276–84. 10.1210/jc.2007-0425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 32.Wild S, Pierpoint T, Jacobs H, McKeigue P. Long-term consequences of polycystic ovary syndrome: results of a 31 year follow-up study. Hum Fertil. (2000) 3:101–5. 10.1080/1464727002000198781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yildiz BO, Bozdag G, Yapici Z, Esinler I, Yarali H. Prevalence, phenotype and cardiometabolic risk of polycystic ovary syndrome under different diagnostic criteria. Hum Reprod. (2012) 27:3067–73. 10.1093/humrep/des232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wild S, Pierpoint T, McKeigue P, Jacobs H. Cardiovascular disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome at long-term follow-up: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Endocrinol. (2000) 52:595–600. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01000.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Unluturk U, Harmanci A, Kocaefe C, Yildiz BO. The genetic basis of the polycystic ovary syndrome: a literature review including discussion of PPAR-gamma. PPAR Res. (2007) 2007:49109. 10.1155/2007/49109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alsamarai S, Adams JM, Murphy MK, Post MD, Hayden DL, Hall JE, et al. Criteria for polycystic ovarian morphology in polycystic ovary syndrome as a function of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2009) 94:4961–70. 10.1210/jc.2009-0839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmidt J, Brannstrom M, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Dahlgren E. Reproductive hormone levels and anthropometry in postmenopausal women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a 21-year follow-up study of women diagnosed with PCOS around 50 years ago and their age-matched controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2011) 96:2178–85. 10.1210/jc.2010-2959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. (2019) 139:e56–528. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armeni E, Lambrinoudaki I. Cardiovascular Risk in Postmenopausal Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. (2019) 17:579–90. 10.2174/1570161116666180828154006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hernández-Reséndiz S, Muñoz-Vega M, Contreras WE, Crespo-Avilan GE, Rodriguez-Montesinos J, Arias-Carrión O, et al. Responses of endothelial cells towards ischemic conditioning following acute myocardial infarction. Cond Med. (2018) 1:247–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaur J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. (2014) 2014:943162. 10.1155/2014/943162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Richardson MR. Current perspectives in polycystic ovary syndrome. Am Fam Physician. (2003) 68:697–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellver J, Rodríguez-Tabernero L, Robles A, Muñoz E, Martínez F, Landeras J, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome throughout a woman's life. J Assist Reprod Genet. (2018) 35:25–39. 10.1007/s10815-017-1047-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ueda-Nishimura T, Niisato N, Miyazaki H, Naito Y, Yoshida N, Yoshikawa T, et al. Synergic action of insulin and genistein on Na+/K+/2Cl- cotransporter in renal epithelium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2005) 332:1042–52. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lizneva D, Suturina L, Walker W, Brakta S, Gavrilova-Jordan L, Azziz R. Criteria, prevalence, and phenotypes of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. (2016) 106:6–15. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palomba S, Santagni S, Falbo A, La Sala GB. Complications and challenges associated with polycystic ovary syndrome: current perspectives. Int J Women's Health. (2015) 7:745–63. 10.2147/IJWH.S70314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.