Summary

In clinical medicine, indomethacin (IND, a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug) is used variously in the treatment of severe osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gouty arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis. A common complication found alongside the therapeutic characteristics is gastric mucosal damage. This complication is mediated through apoptosis and autophagy of the gastrointestinal mucosal epithelium. Apoptosis and autophagy are critical homeostatic pathways catalysed by caspases downstream of the gastrointestinal mucosal epithelial injury. Both act through molecular signalling pathways characterized by the initiation, mediation, execution and regulation of the cell regulatory cycle. In this study we hypothesized that dysregulated apoptosis and autophagy are associated with IND‐induced gastric damage. We examined the spectra of in vivo experimental gastric ulcers in male Sprague‐Dawley rats through gastric gavage of IND. Following an 18‐hour fast, IND was administered to experimental rats. They were sacrificed at 3‐, 6‐ and 12‐hour intervals. Parietal cells (H+, K+‐ATPase β‐subunit assay) and apoptosis (TUNEL assay) were determined. The expression of apoptosis‐signalling caspase (caspases 3, 8, 9 and 12), DNA damage (anti–phospho‐histone H2A.X) and autophagy (MAP‐LC3, LAMP‐1 and cathepsin B)‐related molecules in gastric mucosal cells was examined. The administration of IND was associated with gastric mucosal erosions and ulcerations mainly involving the gastric parietal cells (PCs) of the isthmic and upper neck regions and a time‐dependent gradual increase in the number of apoptotic PCs with the induction of both apoptotic (upregulation of caspases 3 and 8) cell death and autophagic (MAP‐LC3‐II, LAMP‐1 and cathepsin B) cell death. Autophagy induced by fasting and IND 3 hours initially prompted the degradation of caspase 8. After 6 and 12 hours, damping down of autophagic activity occurred, resulting in the upregulation of active caspase 8 and its nuclear translocation. In conclusion we report that IND can induce time‐dependent apoptotic and autophagic cell death of PCs. Our study provides the first indication of the interactions between these two homeostatic pathways in this context.

Keywords: apoptosis, autophagy, gastric mucosa, indomethacin, parietal cells

1. INTRODUCTION

In digestive physiology parietal cells (PCs) have an important functional role in the gastric mucosa. When patients are in a fasting state PCs the intracellular canalicular membrane is recruited into the cytoplasm as tubule vesicles with subsequent degradation by autophagy. This is followed by the formation of new tubule vesicles that will be ready to be added to the membrane on activation. During eating these cells have wide intracellular canaliculi with a highly folded membrane studded with H+, K+‐ATPase subunits (proton pumps) for active hydrochloric acid (HCL) production. 1 , 26 , 27 The degradation and recycling of intracellular canaliculi membranes occurs inside autophagosomes. 11 , 56

The gastric mucosa is affected by damaging agents, such as drugs, food and alcohol, that cause gastric ulcerations and erosions. Gastric ulcers are a widely prevalent gastrointestinal disorder affecting 10% of the world’s population, specifically due to the intake of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as indomethacin (IND). 36 , 37 The latter can induce mucosal damage both in cyclooxygenase‐dependent and in cyclooxygenase‐independent pathways. Among these, apoptosis mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress represents cyclooxygenase‐independent mechanisms. 34 Several studies have indicated that IND is able to induce apoptosis and ER stress. 43 , 48

Apoptosis is characterized by nuclear chromatin agglutination and attenuation. Caspases catalyse this. These caspases come in both initiator and executioner forms. 71 The initiator caspases 8 and 9, which usually exist as inactive forms, are activated by dimerization. The executioner caspases 3, 6 and 7 are produced as inactive procaspase dimmers that must be cleaved by initiator caspases to become active. Apoptosis is affected through two central caspase activation cascade pathways: either extrinsic or intrinsic. 3 The extrinsic pathway is triggered by the ligation of specific cell surface death receptors. The latter induces the formation of the death‐inducing signalling complex to cleave and activate caspase 8, which cleaves downstream effector caspases (3, 6 and 7). The activation of the latter leads to DNA fragmentation and apoptosis. 55 , 71 Alternatively, the intrinsic pathway is triggered by intracellular death signals, such as from DNA damage, which results in alteration of mitochondria with the release of cytochrome c and the subsequent transduction of various signals into caspase activity. The latter include activation of the initiator caspase 9, which activates the effector caspases 3, 6 and 7. 22 , 23

Autophagy, an intracellular regulatory mechanism, mediates cellular stress caused by nutrient deficiencies and leftover dysfunctional growth factors, and includes several types. Micro‐autophagy occurs when intracellular cytosolic elements are phagocytosed directly by lysosome through the lysosomal membrane. Macro‐autophagy involves the delivery of cytoplasmic elements termed 'cargo' to the lysosome via the intermediary of a double membrane–bound vesicle, termed autophagosome (fusion of lysosome). Chaperone‐mediated autophagy is a proteolytic system that mediates the timely degradation of specific proteins and cellular transcription activity accordingly. Other types of autophagy are micro‐ and macropexophagy, nuclear piecemeal micro‐autophagy and the cytoplasm‐to‐vacuole targeting pathway.

Autophagy is a physiologically regulated process involving the recycling of intracellular cytoplasmic organelles, proteins and macromolecules, which mediates the homeostasis of the intracellular environment. 63 When cells are deprived of nutrients/growth factors, or in hypoxic conditions, autophagy provides the necessary means to maintain the intracellular metabolism essential for cell survival. 40 During autophagy isolation membranes are formed which sequester part of the cytoplasm or particular organelle/protein‐forming autophagosomes. These are double‐membraned structures orchestrated by microtubule‐associated protein light chain 3 (MAP‐LC3). The autophagosomes then fuse with endo/lysosomes where they bind to lysosomal‐associated membrane protein 1 or 2 (LAMP‐1, LAMP‐2) forming autolysosomes. Inside the latter, the contents of the cargo are digested by lysosomal cathepsins. 21 , 28 During autophagy, the cytoplasmic form (LC3‐I) is processed and recruited to the autophagosomes where LC3‐II is generated. This results in the formation of cellular autophagosome puncta containing LC3‐II, which is the hallmark of autophagic activation. The autophagic activity is evaluated biochemically by measuring the amount of MAP‐LC3‐II that accumulates in the absence or presence of lysosomal activity. Thus, autophagy seems to play an essential role in IND‐induced small intestinal lesions. 17 , 46 Although the overall importance of autophagy is undisputed, we recognize the role of autophagy in IND‐mediated gastric pathologies has not been explored.

Autophagy and apoptosis crosstalk in several aspects. 16 The crosstalk between autophagic and apoptotic pathways may cooperatively govern the fate of PCs, depending upon the status of these cells and their intracellular signalling environment. 35 Also, both autophagy and apoptosis may modulate cell death independently, and autophagy lies upstream of apoptosis and is required for apoptotic cell death. 7 , 67

Autophagy, unlike apoptosis, is relatively non‐programmed and occurs through different pathways and mediators. Autophagy is upregulated by cellular stress, such as oxidative stress and ER stress. 33 Since ER stress is closely connected with triggering autophagy associated cell death, it is plausible that autophagy could regulate the fate of apoptosis. 32 The protective roles of autophagy in cell survival have been documented by some studies. 6 , 40 , 46 Whether autophagy can protect the gastric mucosa against the deleterious effects of IND has not been yet determined. Moreover, to date, the possible interactions between apoptosis and autophagy in the gastric PCs following the administration of IND have not been investigated. Here, we hypothesize that dysregulated apoptosis and autophagy are associated with IND‐induced gastric damage. To test our hypothesis, we established an animal model. This study presents findings that are novel, to our knowledge, regarding the damaging effects of IND. The following two themes were investigated: damage to PCs following IND treatment and the interaction between autophagy and apoptosis following this treatment.

Our study demonstrates the role of IND in inducing time‐dependent gastric mucosal erosions and ulcerations. At the molecular level, observed morphological changes were linked to a gradual increase in the number of apoptotic PCs, which was associated with an increase in active caspase 3 and caspase 8 expression values in these cells, and not in caspase 9 and caspase 12, indicating that apoptosis occurs via an extrinsic pathway. This IND‐induced apoptosis was associated with an initial induction of autophagy in the PCs (an increase in MAP‐LC3, LAMP‐1 and cathepsin B) followed by downregulation of autophagy. Our study demonstrates that IND treatment causes the death of gastric PCs through both apoptotic and autophagic mechanisms. Furthermore, we show that the luminal PCs in the gastric pits and isthmus gland are the nucleation site of gastric erosion and ulceration.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Primary antibodies

Anti‐proton pump (H+ K+ ATPase β‐subunit) and MAP‐LC3 were obtained from MBL. Cleaved caspase 3 was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Active caspase 8 was obtained from Novus Biologicals. LAMP‐1, caspase 12 and actin (I‐19) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.. Active caspase 9 was obtained from Biorbyt, Cambridgeshire. Anti‐phospho‐histone H2A.X was obtained from Merck KGaA.

2.2. Kits and reagents

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase UTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) kit was obtained from Roche Diagnostics. Cathepsin B Activity Fluorometric Assay Kit was obtained from Bio Vision. VECTASTAIN® ABC Kit, Impact TM, 3, 30‐diaminobenzidine (DAB) and VECTASHIELD® Hard F Set™ Mounting Medium with DAPI were obtained from Vector Laboratories. ECL™ Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent was obtained from Amersham (GE Healthcare).

2.3. Secondary antibodies

EnVision + System‐HRP was obtained from Dako, and streptavidin–biotinylated anti‐rabbit, anti‐mouse and anti‐rat and HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies for Western blotting were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.

2.4. Immunofluorescence double labelling with different antibodies

Alexa Flour 594, 488 and DyLight 488, Thermo Fisher and Cy3, Abcam for immunofluorescence were obtained from xxxx.

2.5. Animals

A total of 60 adult male Sprague‐Dawley rats (230‐60 g) were purchased from Nippon, Charles River.

2.6. Experimental procedure

The rats were handled according to best practices and kept in ventilated metal cages on a 12‐hour light/12‐hour dark cycle at room temperature (22 ± 2°C) and humidity (50% ± 10%). They were fed a standard diet and portable drinking water ad libitum for 3 days before being killed/dispatched, followed by specimen collection/handling.

IND powder (Sigma Aldrich), prepared according to the standard operating procedure manual, at a concentration of 30 mg/kg body weight, 53 was dissolved in three ml hydroxyl propyl cellulose solution (Nippon Soda Co., Ltd.) for each rat.

2.7. Experimental design

The rats were randomly divided into three different groups, including control, fasting and treated. The control group included 12 animals and had ad libitum access to food and water. The fasting group included 12 animals which were deprived of food but not water for 18 hours. The animals in the IND‐treated groups (36 rats) received a single oral dose of IND after an 18‐hour fasting period; 30 mg/kg body weight unfixed tissue samples were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C through gastric gavage. These animals were sacrificed at 3‐, 6‐ and 12‐hour intervals, 12 animals for each period.

Some rats were fixed with intracardiac perfusion of 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and samples were paraffin‐embedded for routine histopathological, immune histochemical, immunofluorescence and TUNEL assay. The animals died within seconds of after intracardiac perfusion of paraformaldehyde. Their stomachs were dissected, opened along the lesser curvature, rinsed in saline and grossly examined. Erosive mucosal lesions were observed with a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMG‐10). Gastric tissue strips (about 2 × 10 mm in size) were taken and further processed for routine histology and light microscopy.

Other rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation following anaesthesia. Fresh unfixed tissue was obtained for Western blotting and protein assays. For Western blotting and fluorometric protein assay, gastric mucosal tissue samples from all groups (without fixation) were rapidly dissected on ice, separated from other layers, rinsed rapidly in sterile saline and immediately placed inside cryotubes in liquid nitrogen, were transported and finally stored in a freezer at −80°C.

2.8. Microscopic evaluation of gastric mucosal damage

Gastric tissue strips of about 2 × 10 mm from all groups were processed for LM microscopy. For light microscope examination, four‐µm‐thick paraffin sections were prepared and stained with Periodic acid–Schiff stains and Mayer’s haematoxylin. 62

2.9. Immunohistochemical evaluation

Four‐µm‐thick tissue sections were subjected to immunohistochemical procedures. 25 The reactions were conducted either with the streptavidin–biotin complex or EnVision horseradish peroxidase (HRP) technique, which was visualized with diaminobenzidine (DAB) and counterstained with haematoxylin. The immunostained sections were examined using a light microscope (Olympus BX50).

2.10. Gastric tissue apoptotic indices using TUNEL assay

We performed terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase‐mediated biotinylated UTP nick end labelling assay according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. 46 The apoptotic nuclei were visualized with DAB, counterstained with haematoxylin and viewed by two observers. Each experimental run included the positive and negative control sections.

2.11. Double‐labelling immunofluorescence

Sections were processed and stained either by a simultaneous or by sequential approach with different primary and secondary antibodies. Sections were counterstained with 4′,6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI). 58 Two observers examined the slides using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP 8). All obtained images were of identical exposure and gain settings.

2.12. Western blotting and protein signal quantification

We carried out Western blotting and protein signal quantification following the manufacturer’s instructions. 17 Briefly, 40 µg of homogenized protein extracts of the gastric mucosa of each group was electrophoretically fractionated on 16% SDS‐PAGE (Tefco) under reducing conditions and transferred into methanol‐activated, 0.2‐mm pore size polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon‐P Transfer Membrane, Millipore). The membrane was immune‐blotted with primary antibodies and matching HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies. The reaction was visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent, visualized by Fusion FX (Vilber Lourmat). Bands were measured in terms of imaging analysis (Image J, NIH). 25 , 58

2.13. Fluorometric protein assay for cathepsin B activity

Cathepsin B activity was determined with 50 µg of gastric mucosa tissue protein extract from each group in triplicate using a fluorometric assay kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 36 , 37 Emerging fluorescence was measured with an excitation filter, 405 nm, and emission filter, 495–505 nm, GloMax Multi‐Detection System (Version 3:00, Promega).

Positive cells for TUNEL, H+, K+‐ATPase, and active nuclear caspase 3 were counted in 12 gastric mucosal sections in high power fields (×200) from three different tissue samples in each group using image software analysis Win Roof version 6.1 (Japan).

Immunofluorescent dots of active caspase 8, LC3 and γH2AX in PCs were counted in 20 PCs in three sections for all groups.

2.14. Statistical analysis

Statistical comparison (Analysis of variance, ANOVA) among groups was performed using statistical package SPSS for Windows, version 16.0. The values were defined of statistical significance as P < .05 and were represented by mean ± SD for each group of the recordings reported by two observers.

3. RESULTS

3.1. IND‐induced gastric mucosal erosions and ulcerations mainly involved the isthmic and neck regions

Within the control groups (healthy‐eating and fasting animals), the mucosa was thrown into longitudinal folds (gastric folds or rugae; Figure 1, 1A,B). However, IND‐treated groups showed early brown haemorrhagic superficial erosion (IND 3 hours), and more profound and deeper erosions extending all through the mucosa at 6 and 12 hours (Figure 1, 1C‐E). On the mucosal surface, there were small, funnel‐shaped depressions (gastric pits). Almost the entire mucosa was occupied by simple, tubular gastric glands, which opened into the bottom of the gastric pits. The surface epithelium was simple tall columnar, mucous‐producing cells. Luminal PCs occurred most frequently in gastric pits, the isthmus and the neck of the glands, where they projected into the lumen of the glands. Few PCs were situated basally, between and below chief cells, in the lower parts of the glands (Figure 1, 2A,B). In the IND‐treated groups, the erosions were more superficial involving mainly the subepithelial layer (lamina propria) followed by superficial sloughing of the covering surface of the mucosal epithelium later on. Full‐thickness sloughing and ulceration of the gastric mucosa occurred 6‐12 hours following treatment with IND. Figure 1, 2C‐E shows a summary of these findings.

Figure 1.

1.1 Gross examination of the stomach showing normal intact glistening pink mucosa in healthy‐eating (A) and fasting 18 h (B). Brown haemorrhagic superficial erosions (arrow) are demonstrated at early time IND 3 h (C), deeper at 6 h (D) and 12 h (E). 1.2. Photomicrographs of the gastric mucosal tissue. A, The gastric mucosa appears unremarkable in the control group (animals eating normally). B, The gastric mucosa appears unremarkable in the animals fasting for 18 h. C‐E, In IND‐treated animals, there are superficial erosions involving the isthmic and neck regions of the gastric mucosa, together with sloughing of overlying superficial cells (arrows) at 3 h (C). Ulceration (arrow) of the gastric mucosa occurred after 6 h (D) and 12 h (E). (PAS and haematoxylin)

3.2. IND‐induced a time‐dependent gradual increase in the number of apoptotic gastric PCs

Through TUNEL, in both control groups, minimal apoptosis was seen (Figure 2, 1A,B). In contrast, TUNEL‐positive cells showed a time‐dependent gradual increase in the number of apoptotic PCs (3, 6 and 12 hours) following the intake of IND (Figure 2, 1F). The end labelling was localized in the nuclei, indicating extensive apoptotic DNA fragmentation within the nuclei of the PCs. The apoptotic luminal PCs detached (anoikis) into the lumen of the gastric glands at 3 hours and then were out of the lumen at 6 hours (Figure 2, 1C‐E). The IND‐induced PC apoptosis at 6 and 12 hours was associated with a concomitant time‐dependent significant decrease in the number of PCs (H+, K+‐ATPase beta subunit, a marker of PCs). A summary of these findings is shown in Figure 2, 2A‐F.

Figure 2.

2.1. Photomicrograph of gastric mucosa showing very few TUNEL‐positive cells on the surface epithelium in healthy‐eating (A) and in fasting 18‐h groups (B). TUNEL‐positive cells are located at the isthmic and neck regions of the mucosal glands in IND‐treated groups (arrow) after 3 h (C), exfoliated after 6 and 12 h (D,E). Note, the PCs with positive nuclei shown in the insets. Counting of stained cell nuclei and statistical analysis proved the significant and time‐dependent increase in TUNEL‐positive cells (F) after IND treatment (#: non‐significant, *P < .05, **P < .001). 2.2. Photomicrographs of the gastric mucosa showing H+ K+ ATPase ß‐subunit–positive cells (PCs, parietal cells) which are normally distributed along the entire gastric glands in the control group (A: animals eating normally) and in the animal fasting for 18 h (B). Exfoliation of these cells at the site of damage occurred at the surface after 3, 6 and 12 h (red arrows, C, D and E respectively). We counted of the cells with cytoplasmic staining cell, and there was a statistically significant time‐dependent decrease in PCs at a time starting at 6 till 12 h following IND treatment (F) (#: non‐significant, *P < .05, **P < .001, the red asterisk means decrease)

3.3. An IND‐induced caspase 3–dependent gastric PC apoptosis

An IND‐induced time‐dependent activation of caspase 3 in PCs (Figure 3, 1A‐F) shows that there is caspase 3 co‐localization in PCs with apoptosis as confirmed with double‐labelling immunofluorescence. This was observed within the nuclei of PCs after 3 hours and occurred mainly within the nucleus in IND 6 and 12 hours (Figure 3, 2).

Figure 3.

3.1. Photomicrographs of gastric mucosa showing cleaved caspase 3–positive cells. There are very few positive nuclei in healthy‐eating (A) and few at the gastric pit and upper part of the neck in fasting 18 h (B). IND‐treated groups showing a time‐dependent increase in cleaved caspase 3–positive cells at the site of mucosal damage (arrow) after 3, 6 and 12 h (C‐E). Note, the positively stained nuclei of PCs in the inset. Counting of stained cell nuclei and statistical analysis proved the time‐dependent and significant increase in cleaved caspase 3–positive cells in IND‐treated groups at the site of mucosal damage (F) ( #: non‐significant, *P < .05). 3.2. Photomicrographs of gastric mucosa stained by double‐labelling immunofluorescence of active caspase 3 (green dots) and PCs (red) marker showing co‐localization of active caspase 3 inside PC nucleus (arrow) in IND‐treated group, and the double labelling appears few intranuclear after 3 h (left panel) but mainly nuclear after 6 h (middle panel) and 12 h (right panel)

3.4. IND‐induced caspase 8 (extrinsic pathway) but not caspase 9 or caspase 12 (intrinsic pathway) in the gastric PCs

In control groups, we observed cytoplasmic expression of active caspase 8 mainly in the PCs. However, it appeared to be nuclear and increased after IND treatment (Figure 4, 1A‐E). Active caspase 8 co‐localization in PCs was confirmed with double‐labelling immunofluorescence. It was observed within the cytoplasm in control groups and started to appear within the nucleus after 3 hours and occurred mainly within the nucleus in IND 6 and 12 hours (Figure 4, 2A‐F). Furthermore, the simple active caspase 8 to actin ratio was expressed and, using Western blotting, was found to increase after IND treatment (Figure 6, 3A,B). In contrast, in PCs of IND‐treated rats, we found a lack of expression of caspase 9 (mitochondrial) and caspase 12 (ER) (data not shown).

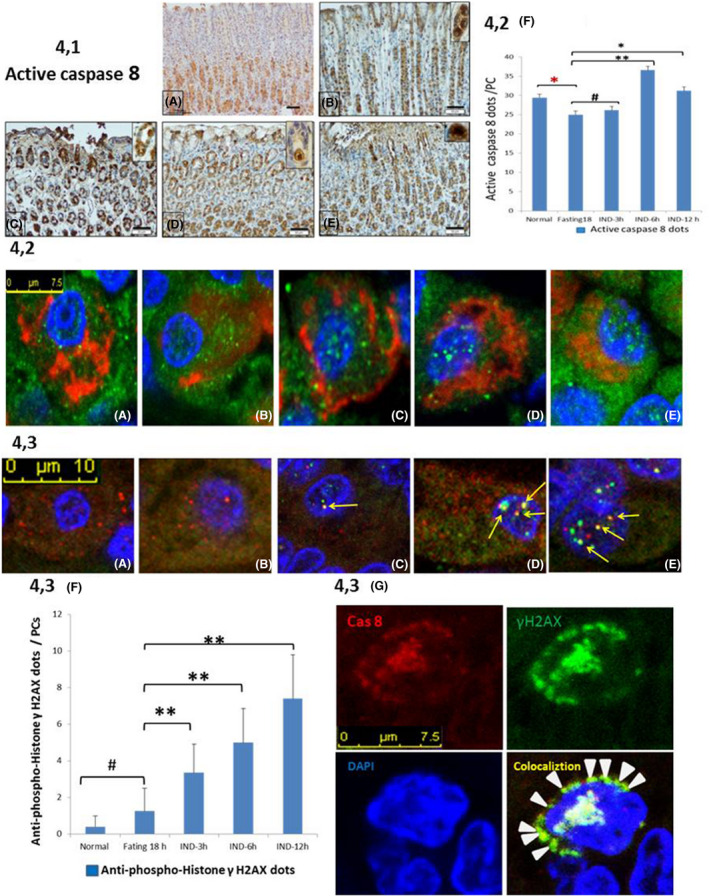

Figure 4.

4.1. Photomicrographs of gastric mucosa showing active caspase 8–positive cells. There are few positive cells at the gastric pits and the upper part of the neck in healthy‐eating (A), fasting 18 h (B) and after 3 h of IND (C) groups. IND‐treated groups showing a time‐dependent increase in active caspase 8–positive cells at the site of mucosal damage after 6 and 12 h (D,E). Note, the positivity is cytoplasmic in healthy‐eating (A), fasting 18 h (B) but nuclear in few PCs after 3 h that increased after 6 and 12 h (D,E) as shown in the insets. 4.2. Photomicrographs of gastric mucosa stained by double‐labelling immunofluorescence of active caspase 8 (green dots) and PC (red) marker showing co‐localization of active caspase 8 inside PC cytoplasm in normal (A) and in fasting 18‐h (B) groups. In IND‐treated group, the double labelling appears few intranuclear after 3 h (C) but mainly nuclear after 6 h (D) and 12 h (E). Counting of co‐localized dots and statistical analysis (F) proved the time‐dependent and significant increase in active caspase 8 in PCs in IND‐treated groups (#: non‐significant,*P < .05, **P < .001, red asterisk = decrease and black asterisk = increase). 4.3 Double‐labelling immunofluorescence of active caspase 8 (red dots) and γ H2A.X (green dots) showing few cytoplasmic red dots in healthy‐eating (A) and fasting 18‐h (B) groups. In contrast, there is an apparent nuclear co‐localization (yellow dots pointed by arrows) of active caspase 8 and γ H2AX in IND‐treated group at 3 h (C) and 6 h (D) increased in IND 12 h (E). A perinuclear ring of co‐localization (arrowhead) appeared at IND 6‐h–treated group (4.3 G). Counting of γ H2A.X dots and statistical analysis (F) proved the time‐dependent and significant increase in γ H2A.X in PCs in IND‐treated groups (#: non‐significant, **P < .001)

Figure 6.

6.1. Double‐labelling immunofluorescence of active caspase 8 (green dots) and MAP‐LC3 (red dots) showing the presence of few cytoplasmic co‐localization (yellow dots pointed by the arrow) in the healthy‐eating group (A). In contrast, numerous co‐localization of caspase 8 and LC3 is present in fasting 18 h (B) and IND 3 h (C) with few co‐localization in 6 h and very few in IND 12 h. Note, dots of active caspase 8 appear intranuclear (D&E). 6.2. Double‐labelling immunofluorescence of caspase 8 (red dots) and Lamp‐1 (green dots) showing few co‐localization (yellow dots pointed by the arrow) in a healthy‐eating group (A). In contrast marked co‐localization of active caspase 8 and Lamp‐1 is present in fasting 18 h (B) and in IND 3 h (C) with few co‐localization in 6 h (D) and very few in IND 12 h (E). A photograph (A) showing Western blot analysis of the whole gastric mucosa active caspase 8, anti‐phospho‐histone γ H2A.X and MAP‐LC3. 6.3.B analysis of western blotting of LC3I versus LC3II Note, the western blot analysis of the three parameters between different groups and time intervals; active caspase 8 level decreases in fasting 18 h and treated 3h (but increased in IND‐treated groups after 6 and 12 h). γ H2A.X shows little increase in fasting 18 h and more in IND‐treated groups by time intervals. MAP‐LC3 increases in fasting 18 h and in 3 h after IND‐treated group and dropped after 6‐ and 12‐h IND‐treated groups

3.5. Active caspase 8–induced nuclear double‐stranded DNA damage in the IND‐treated groups

Within IND‐treated groups, there was a time‐dependent increase in the co‐localization of active caspase 8 and anti‐phospho‐histone γH2AX in the nuclei of the PCs (Figure 4, 3A‐F), appearing as a peripheral nuclear ring early after 6 hours of IND treatment (Figure 4, 3G) These findings were congruent with the results of the Western blotting of anti‐phospho‐histone γH2AX (Figure 6, 3A,B).

3.6. IND‐mediated induction of the autophagic (MAP‐LC3) marker in the gastric PCs

In fasting and IND treatment (after 3 hours), there was enhanced autophagy manifested in increased expression of MAP‐LC3‐II. Alternatively, IND treatment (6 and 12 hours) was associated with the dampening down of autophagy (decreased MAP‐LC3‐II expression). A summary of these results as shown by immunohistochemistry (Figure 5, 1A‐E) and immunofluorescence (Figure 5, 2A‐F) is shown. Quantification of LC3 puncta is a valid method for determining the induction of autophagy but increased numbers of puncta do not necessarily mean increased autophagy. Increased numbers of LC3 puncta may also be observed when the completion of autophagy is inhibited, which results in an accumulation of puncta. Therefore, it is more appropriate to use a method that gauges autophagic flux, such as measuring the conversion of LC3‐I to LC3‐II. The ratio of LC3‐II to LC3‐I at 18 hours in fasting animals increased, indicating the initiation of autophagy and increased conversion of LC3‐I to LC3‐II compared with the normal group, and thus signifying increased autophagic flux. In IND‐treated animals (3‐hour interval), the ratio of LC3‐II to LC3‐I was further increased, indicating a further increase in autophagic flux than at initiation, which was confirmed by a concomitant increase in the activity of cathepsin B (lysosomal activity). Later on (6‐ and 12‐hour intervals of IND treatment), the ratio decreased, implying cessation of the conversion of LC3‐I to LC3‐II. However, Mizushima and Yoshimori 44 stated that Western immunoblotting tends to be much more sensitive to LC3‐II than LC3‐I, so it is recommended to simply use the LC3‐II level rather than the ratio. A summary of these findings is shown in Figure 6, 3A‐C.

Figure 5.

5.1 Photomicrographs of gastric mucosa showing MAP‐LC3–positive cells mostly in the basal part and few in the luminal part of the gastric glands in the healthy‐eating group (A). However, luminal part of the gland shows an increase in the positive cells in fasting 18 h (B) and in IND 3‐h (C) but decreases in IND 6‐h (D) and IND 12‐h (E) groups. Note, the cytoplasmic positivity in PC is shown in the inset. Note, the damaged area is pointed by the arrow. 5.2 Double‐labelling immunofluorescence of LC3 (green dots) and PC marker (red) showing minimal co‐localization of MAP‐LC3 inside luminal PCs cytoplasm in normal (A) and increased in fasting 18‐h (B) groups. In IND‐treated groups, the double labelling appears maximally in 3‐h (C) and damped down in 6‐h (D) and 12‐h (E) IND‐treated groups. Counting of co‐localized dots and statistical analysis (F) proved the significant increase in LC3 and PC IF in fasting 18 h and in 3 h after IND‐treated groups and damped down in 6‐h and 12‐h IND‐treated groups (*P < .05, **P < .001, red asterisk = decrease and black asterisk = increase). 5.3. A diagram (C) showing an increase in fluorometric protein assay of cathepsin B in fasting 18 h and in 3 h after IND‐treated groups and damped down in 6‐h and 12‐h IND‐treated groups (*P < .05, **P < .001, red asterisk = decrease and black asterisk = increase)

3.7. IND‐mediated upregulation of lysosomal activity (cathepsin B) markers in the gastric PCs

We found that fasting and IND treatment (3 hours) showed enhanced lysosomal enzyme activity as evidenced by upregulation of cathepsin B activity revealed in the fluorometric protein assay. Alternatively, IND treatment (6 and 12 hours) was associated with the dampening down of autophagy–lysosomal activity (downregulation of cathepsin B activity; Figure 5, 3).

3.8. Crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy in the gastric PCs

Fasting and IND treatment (after 3 hours) were associated with strong co‐localization between caspase 8 and LC3 (Figure 7). Alternatively, this co‐localization decreased in the IND‐treated groups (6‐ and 12‐hour periods). A summary of these results is shown in Figure 6, 1A‐E.

Figure 7.

Diagram summarizing the hypothesis of the mechanism of IND‐induced gastric PC damage. It is plausible to propose that modifying autophagy may have therapeutic ramifications against IND‐induced gastric mucosal damage. Taken as a whole, since IND‐induced apoptosis or autophagy seems to be allied to licence the PCs fate, optimal modulation of autophagy can be a therapeutic strategy to attenuate IND‐associated gastric damages. However, extensive large‐scale experimental work is mandated to investigate how IND could inhibitor abort autophagy could be a leading strategy to rescue gastric mucosa from damage. This effect could be due to cleavage of specific autophagic proteins or genes either directly or indirectly through upregulation of active caspase 8 (blue arrow = increase or upregulation, while red arrows = decrease or downregulation)

3.9. Autophagy induced active caspase 8 degradation at 3 hours in the IND‐treated groups in the gastric PCs

There was strong co‐localization between active caspase 8 and Lamp‐1 lysosomal enzyme, indicating that active caspase 8 undergoes degradation inside autolysosomes. A summary of these results is shown in Figure 6, 2A‐E.

4. DISCUSSION

IND is a commonly prescribed drug with several shortcomings, including peptic ulceration, haemorrhage and perforation. Morphologically, the intake of IND is associated with damage to the gastric epithelial cells; understanding the underlying mechanisms of this cellular damage will aid in the development of a therapeutic strategy to ameliorate it. Since apoptosis in association with autophagy is a process occurring along with ER cell stress, it is conceivable that there is some crosstalk between the apoptotic and autophagic pathways. To date, our knowledge about the association between apoptotic and autophagic cell death in the gastric PCs is limited. Further insights regarding these observations were gleaned through a rat animal model examining the histopathological changes and underlying molecular alterations of apoptosis and the safeguarding autophagic machinery of the fasting gastric mucosa associated with the intake of IND.

In the current study, we investigated the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying IND‐induced gastric damage. We found that PCs underwent apoptosis through an extrinsic rather than intrinsic autophagy pathway. This occurs through the activation of caspase 8. Autophagy was investigated through the analysis of some autophagy‐related markers. The interplay between autophagy and apoptosis in IND‐induced damage in gastric PCs was investigated by studying active caspase 3 and caspase 8 and autophagy markers (LC3, LAMP‐1 and cathepsin B). We made several observations. Autophagy was upregulated early after IND administration (3 hours) to protect the gastric mucosal cells, especially luminal PCs, from cellular stress induced by IND. This protective effect was mediated by the degradation of active caspase 8 inside autolysosomes. Later on (6‐12 hours after IND administration), autophagy was inhibited as indicated by downregulation of both LC3‐II and cathepsin B activity with upregulation of active caspase 8, leading to apoptotic cell death with autophagic features.

4.1. IND‐induced gastric mucosal erosions and ulcerations mainly involving the isthmic and neck regions

Our study revealed that IND provoked gastric mucosal injury starting 3 hours after drug administration in the gastric pit and upper neck region with sloughing of the overlying surface mucosal epithelium. Mucosal damage became deeper with time until almost all mucosal layers were damaged (ulceration) at 12 hours. This mucosal injury may have been due to the impairment of mucosal blood flow, superoxide radical generation and the inhibitory effect of IND on prostaglandin synthesis 64 with the induction of apoptosis. At the molecular level, these changes were associated with the loss of the adhesion molecules, weakened integrity of the gastric glands and disturbance of the epithelial barrier, which caused these cells to be subjected to more acidic components. 2 The IND‐induced gastric mucosal damage and dissociation of the luminal PCs as revealed by our study agree with previous studies. 9 , 15 , 37 , 51 , 54 . The significant time‐dependent (from IND 6‐12 hours) decrease in the number of the PCs (stained with anti‐proton pump H+, K+‐ATPase β‐subunit) was consistent with the results of the gross and histopathological assessment, as well as with previous studies. 42

4.2. IND‐induced time‐dependent gradual increase in the number of apoptotic gastric PCs

In agreement with other studies, our current work demonstrated the ability of IND to induce time‐dependent PC apoptosis. 10 , 12 , 19 , 24 Apoptotic PCs were seen histologically and by TUNEL as exfoliated apoptotic cells in the gastric gland lumens and up through the lumen to the epithelium with pyknotic nuclei or TUNEL‐positive cells. This morphology signifies a particular type of apoptosis which is associated with detachment of the luminal lining epithelial cells and is known as anoikis (cell‐detachment‐induced apoptosis). Anoikis can occur through integrin‐mediated cell death, which involves the recruitment of caspase 8 to the integrin‐β‐subunit cytoplasmic domain and initiation of an apoptotic response. 14 IND‐induced PC apoptosis may be attributed to the production of ROS followed by a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential. 8 The latter is believed to induce ROS production, and therefore, a vicious cycle ameliorates the process of oxidative stress, leading to apoptosis. 39 , 59 , 60 Moreover, PC apoptosis is related to the induction of tumour necrosis factor‐α and caspase 3. The amplification and propagation of the cell death signalling cascade induced by TNF‐α and caspases remain under the regulatory control of nitric oxide. 45 , 59 , 60 Induction of apoptosis of intact gastric mucosal epithelial cells following IND administration may also be due to the direct apoptotic effect of IND on gastric epithelial cells. On the other hand, IND may induce some other intermediate mediators or inflammatory cytokines that induce apoptosis in rat gastric mucosal cell lines. 30

4.3. IND‐induced caspase 3‐ and caspase 8–dependent gastric parietal cell apoptosis

The salient point of the present study is that IND activates caspase 3–dependent apoptotic PC death. The upregulation of caspase 3 and caspase 8 expression in the gastric PC following IND treatment concurs with other studies. 12 , 50 , 72 A rat gastric mucosal cell line, RGM1, was used to examine the molecular changes following IND intake and stated that it induces caspase 3–like protease activation followed by apoptosis in a dose‐ and time‐dependent manner. It also enhanced mitochondrial cytochrome c release in a time‐dependent fashion. 12 Studies have reported the activation of caspase 3 (a 3.9‐fold increase in mucosal expression of caspase 3 activity), and the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase following IND intake. 60 Some researchers examined the anti‐apoptotic effects of lansoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, in the gastric mucosa following the intake of IND. Lansoprazole prevented IND‐induced activation of caspase 8 and accordingly favoured mucosal cell renewal. 38 Here, we showed for the first time (using co‐localization of active caspase 3 and anti‐proton pump H+, K+‐ATPase β‐subunit), to our knowledge, that IND‐induced apoptotic cell death characteristically involves PCs, especially luminal PCs. This possibly novel finding indicates that luminal PCs in the gastric pit and isthmus are the nucleation site of gastric erosion and ulceration, which is supported by a previously postulated theory. 52 Caspase 3 is activated in the apoptotic cell both by intrinsic (mitochondrial) and by extrinsic (death ligand) programmed cell death pathways. Caspase 3 is activated by upstream caspase 8 and caspase 9 because it functions as a convergence point for different signalling pathways.

4.4. IND‐mediated induction of the autophagic (MAP‐LC3) and lysosomal (cathepsin B) markers in gastric PCs

MAP‐LC3 is a mammalian homologue of yeast ATG8. The latter is an important marker and effector molecule of autophagy. MAP‐LC3 is a major constituent of the autophagosome; it is involved in cargo recruitment into autophagosomes and also the biosynthesis of autophagosomes, which represent a double‐membraned structure that helps sequester the target organelle/protein. They then fuse with endo/lysosomes where the contents—and MAP‐LC3—are degraded. Our study revealed the expression of MAP‐LC3 (key readout of levels of autophagy) in the luminal PCs and lack of expression at the base of the glands supporting the functional heterogeneity of gastric PCs along the gland axis. 26 , 27 The increased expression of MAP‐LC3 in PCs during fasting indicates a role for autophagy in challenging starvation and supplying the essential needs of the cells. On the other hand, the increased MAP‐LC3 expression following initial IND intake (3 hours) suggests the role of autophagy in combating IND‐induced cellular stress. Our findings are in agreement with other studies. 6 Previous investigations examined the relationships between autophagy and ethanol‐induced gastric damage. They found that ethanol can trigger autophagy through the downregulation of mTOR signalling. Autophagy, in turn, suppresses the formation of ROS and the degradation of antioxidant and lipid peroxidation, thereby decreasing generation of the cellular oxidative stress response. 6 Cell survival during stress can occur through Atg5‐ and Atg7‐dependent (conventional pathway) and Atg5/Atg7‐independent pathways of autophagy. Atg5/Atg7‐independent (alternative) pathways are not associated with MAP‐LC3 processing but appear to specifically involve autophagosome formation from late endoscopes and the trans‐Golgi. 47 In our series, it is still plausible that prolonged exposure to IND (at 6 and 12 hours) induced autophagy through the Atg5/Atg7‐independent pathway. The process of macro‐autophagy was examined in mouse cells lacking Atg5 or Atg7, which revealed that mouse cells can still form autophagosomes/autolysosomes and perform autophagy‐mediated protein degradation when exposed to certain unfavourable conditions. This alternative process of macro‐autophagy is controlled by some autophagic proteins, such as Unc‐51‐like kinase 1 and Beclin 1. 47 Knowing whether such proteins are involved in PC IND‐induced autophagy requires further investigation. We used cathepsin B (a lysosomal enzyme) involved in autophagic degradation—a more specific method for measuring lysosomal enzyme activity during autophagy flux at different time intervals in the experiment. Its increased activity (as revealed by fluorometric protein assays) indicates increased lysosomal degradation early in the IND‐treated mucosal cells (at 3 hours) possibly to combat IND‐induced cellular stress. There was a subsequent marked decrease in cathepsin B levels (6 and 12 hours) after IND treatment. The inhibitory effect of IND on lysosomal cathepsin B was proved previously in rat spleens 68 and gastric cancer cells. 65 Lysosomal cathepsin B inhibition together with the dampening down of autophagy (decreased MAP‐LC3 expression) was congruent with lapidated LC3‐II levels. Taken together, these data indicate that the cytoprotective effect of autophagy is only activated at fasting and early on (3 hours) following IND intake,however, it is aborted at 6 and 12 hours after IND administration.

4.5. The interplay between apoptosis and autophagy in gastric parietal cells

Autophagy and apoptosis are two interrelated types of machinery, and the fate of the cell is determined according to their balance in response to cytotoxic stress. 13 , 16 , 41 To examine the possible crosstalk between apoptosis and autophagy, we performed double‐labelling immunofluorescence of active caspase 8 and autophagosomal marker MAP‐LC3. There was co‐localization between caspase 8 and MAP‐LC3 in the IND‐treated gastric PCs, indicating interplay between apoptotic and autophagic machinery. We found that fasting and IND treatment (after 3 hours) were associated with strong co‐localization between caspase 8 and MAP‐LC3. This co‐localization decreased in IND‐treated animals (at 6‐ and 12‐hour intervals). To test whether autophagy affects caspase 8 activation or degradation, we performed double‐labelling immunofluorescence of active caspase 8 and lysosomal surface protein (LAMP‐1), and found co‐localization, indicating that autophagy degrades active caspase 8 inside autophagolysosomes. 20 , 70

These findings indicate that cleaved caspase 8 undergoes degradation inside autolysosomes. It is conceivable that fasting and an initial IND treatment (at 3‐hour period) induced apoptosis and autophagy. The latter prompted the degradation of caspase 8 inside PCs. Further IND treatment (at 6‐ and 12‐hour periods) was associated with damping down of autophagy resulting in accumulation of active caspase 8. As revealed by our study, the increased activity of MAP‐LC3 and cathepsin B (fasting and following 3‐hour treatment with IND) is likely responsible for the degradation of cleaved caspase 8. Our results coincide with earlier investigations. 20 Hou et al reported the expression pattern and subcellular localization of active caspase 8 in TRAIL‐mediated autophagy and the autophagy‐to‐apoptosis shift upon autophagy inhibition. They used Bax (−/−) Hct116 cells that are TRAIL‐resistant, despite significant DISC processing of caspase 8, and a caspase 8–specific antibody. They determined that the TRAIL‐mediated autophagic response counter‐balances the TRAIL‐mediated apoptotic response. This was mediated through continuous sequestration of the large caspase 8 subunit in autophagosomes and its subsequent elimination in lysosomes. 20 With damping down of autophagy (at 6 and 12 hours), active caspase 8 levels began to increase 70 subsequently with double‐stranded DNA damage and cleaved caspase 3 activity increased. These findings agree with other studies. The effects of tunicamycin on HepG2 cells have been previously studied. Tunicamycin induced caspase‐dependent apoptosis pathway with increased activity of caspases 3/7, 8 and 9. This was associated with an increased level of LC3II and activation of Beclin 1. The inhibition of autophagy efficiently promoted IND‐induced cell death. The apoptotic cell rate and caspase 3 activation were significantly enhanced following aborted autophagy. 70 These results coincide with autophagy inhibition and epithelial cell damage of the gastrointestinal tract induced by aspirin. 18 However, it is still plausible that the increase in active caspase 8–cleaved Atg3 can inhibit autophagy. 49

As in previous studies, we report the translocation of active caspase 8 into the nuclei of the PCs following IND treatment. 4 Active caspase 8 translocated into the nucleus could possibly either activate caspase 3 4 , 57 or induce direct DNA damage. 61 To investigate the underlying effect of its nuclear translocation, we performed double‐labelling immunofluorescence of cleaved caspase 8 with histone H2AX‐associated DNA damage. Interestingly, we found time‐dependent nuclear co‐localization of cleaved caspase 8 with anti‐phospho‐histone γH2AX–associated DNA damage (γH2AX) in the PCs of the IND‐treated group with a peripheral nuclear ring (at 6 hours IND treatment) and intranuclear localization with increasing time of IND treatment. These observations concur with the results that death receptor pathways induce double‐stranded DNA breaks and appear as a peripheral ring at early apoptosis. 61 Western blotting of cleaved caspase 8 and γH2AX further confirmed their increase with time, with a marked increase at IND 6 hours and which remained high at IND 12 hours.

In conclusion, our study model demonstrated that IND causes cellular stress and affects the gastric PCs mainly in the luminal region; we also observed alterations in both apoptotic and autophagic apparatus. Autophagy is a protective cellular mechanism, with delayed apoptosis which preserves cell life. This may occur via a two‐step approach: first active caspase 8 is autophaged within autophagosomes; second, active caspase 8 is further degraded within autolysosomes. This is time‐dependent, and failure of autophagy to compensate cellular life will upscale apoptosis, accompanied by upregulation of active caspase 8. Our study also demonstrated nuclear DNA damage through active caspase 8 nuclear translocation, which represents a novel mechanism.

In this context, we propose a new mechanism for IND‐induced damage in the gastric mucosa: nuclear translocation of active caspase 8 and aborted autophagy leads to gastric PC apoptosis and mucosal injury respectively.

Our current findings do not confirm whether this autophagy results in cell death and tissue damage or acts as a pro‐survival response. To reach this conclusion, further experiments are needed in which rats would need to be treated with IND in combination with either an autophagy inhibitor, such as 3‐methyladenine, chloroquine 6 , 46 , 66 , 69 or apoptosis inhibitors (pancaspase inhibitors) such Z‐VAD‐FMK (carbobenzoxy‐valyl‐alanyl‐aspartyl‐[O‐methyl]‐ fluoromethylketone). 5 , 29 , 31 Alternatively, tissue damage could be compared after IND administration in wild‐type and autophagy‐deficient animals.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

In this study, the experimental design, animal care and procedures were all conducted following best practices approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee guidelines of Osaka Medical College, Approval Code No. 27104‐No. 28089.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There were no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Yuko Ito, Masa‐Aki Shibata, KentaroMaemura, Eman E. Abu‐Dief, Usama M Abdelaal, Hoda M Elsayed, Yoshinori Otsuki and Kazuhide Higuchi participated in research design, performed data analysis and contributed new reagents or analytic tools. Sahar M Gebril conducted experiments and performed data analysis. Mahmoud R. Hussein performed data analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The study is supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Sohag University.

Gebril SM, Ito Y, Shibata M‐A, et al. Indomethacin can induce cell death in rat gastric parietal cells through alteration of some apoptosis‐ and autophagy‐associated molecules. Int J Exp Path. 2020;101:230–247. 10.1111/iep.12370

References

- 1. Aoyama F, Sawaguchi A. Functional transformation of gastric parietal cells and intracellular trafficking of ion channels/transporters in the apical canalicular membrane associated with acid secretion. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:813–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aoyama F, Sawaguchi A, Ide S, Kitamura K, Suganuma T. Exfoliation of gastric pit‐parietal cells into the gastric lumen associated with a stimulation of isolated rat gastric mucosa in vitro: a morphological study by the application of cryotechniques. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;129:785–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Banjerdpongchai R, Kongtawelert P, Khantamat O, et al. Mitochondrial and endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways cooperate in zearalenone‐induced apoptosis of human leukemic cells. J Hematol Oncol. 2010;3:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benchoua A, Couriaud C, Guegan C, et al. Active caspase‐8 translocates into the nucleus of apoptotic cells to inactivate poly(ADP‐ribose) polymerase‐2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:34217–34222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bockerstett KA, Osaki LH, Petersen CP, et al. Interleukin‐17A promotes parietal cell atrophy by inducing apoptosis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;5:678–690.e671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chang W, Bai J, Tian S, et al. Autophagy protects gastric mucosal epithelial cells from ethanol‐induced oxidative damage via mTOR signaling pathway. Exp Biol Med. 2017;242:1025–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen S, Zhou L, Zhang Y, et al. Targeting SQSTM1/p62 induces cargo loading failure and converts autophagy to apoptosis via NBK/Bik. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:3435–3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chung YM, Bae YS, Lee SY. Molecular ordering of ROS production, mitochondrial changes, and caspase activation during sodium salicylate‐induced apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Filaretova LP, Bagaeva TR, Morozova OY, Zelena D. A wider view on gastric erosion: detailed evaluation of complex somatic and behavioral changes in rats treated with indomethacin at gastric ulcerogenic dose. Endocr Regul. 2014;48:163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fuji Y, Matsura T, Kai M, Kawasaki H, Yamada K. Protection by polaprezinc, an anti‐ulcer drug, against indomethacin‐induced apoptosis in rat gastric mucosal cells. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2000;84:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fujii T, Fujita K, Takeguchi N, Sakai H. Function of K(+)‐Cl(‐) cotransporters in the acid secretory mechanism of gastric parietal cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:810–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fujii Y, Matsura T, Kai M, Matsui H, Kawasaki H, Yamada K. Mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase‐3‐like protease activation during indomethacin‐induced apoptosis in rat gastric mucosal cells. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;224:102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gordy C, He YW. The crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis: where does this lead? Protein Cell. 2012;3:17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guadamillas MC, Cerezo A, Del Pozo MA. Overcoming anoikis–pathways to anchorage‐independent growth in cancer. J Cell Scis. 2011;124:3189–3197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guidobono F, Pagani F, Ticozzi C, Sibilia V, Pecile A, Netti C. Protection by amylin of gastric erosions induced by indomethacin or ethanol in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:581–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gump JM, Thorburn A. Autophagy and apoptosis: what is the connection? Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:387–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harada S, Nakagawa T, Yokoe S, et al. Autophagy deficiency diminishes indomethacin‐induced intestinal epithelial cell damage through activation of the ERK/Nrf2/HO‐1 pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;355:353–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hernandez C, Barrachina MD, Vallecillo‐Hernandez J, et al. Aspirin‐induced gastrointestinal damage is associated with an inhibition of epithelial cell autophagy. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:691–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirata I, Naito Y, Handa O, et al. Heat‐shock protein 70‐overexpressing gastric epithelial cells are resistant to indomethacin‐induced apoptosis. Digestion. 2009;79:243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hou W, Han J, Lu C, Goldstein LA, Rabinowich H. Autophagic degradation of active caspase‐8: a crosstalk mechanism between autophagy and apoptosis. Autophagy. 2010;6:891–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huang WP, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy in yeast: a review of the molecular machinery. Cell Struct Funct. 2002;27:409–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hussein MR. Apoptosis in the ovary: molecular mechanisms. Hum Reprod Update. 2005;11:162–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hussein MR, Haemel AK, Wood GS. Apoptosis and melanoma: molecular mechanisms. J Pathol. 2003;199:275–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Imamine S, Akbar F, Mizukami Y, Matsui H, Onji M. Apoptosis of rat gastric mucosa and of primary cultures of gastric epithelial cells by indomethacin: role of inducible nitric oxide synthase and interleukin‐8. Int J Exp Pathol. 2001;82:221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ito Y, Shibata M‐A, Eid N, Morimoto J, Otsuki Y. Lymphangiogenesis and axillary lymph node metastases correlated with VEGF‐C expression in two immunocompetent mouse mammary carcinoma models. Int J Breast Cancer. 2011;2011:867152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Karam SM, Li Q, Gordon JI. Gastric epithelial morphogenesis in normal and transgenic mice. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G1209–G1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karam SM, Yao X, Forte JG. Functional heterogeneity of parietal cells along the pit‐gland axis. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G161–G171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kelekar A. Introduction to the review series autophagy in higher eukaryotes‐ a matter of survival or death. Autophagy. 2008;4:555–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Keoni CL, Brown TL. Inhibition of apoptosis and efficacy of pan caspase inhibitor, Q‐VD‐OPh, in models of human disease. J Cell Death. 2015;8:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kusuhara H, Matsuyuki H, Matsuura M, Imayoshi T, Okumoto T, Matsui H. Induction of apoptotic DNA fragmentation by nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs in cultured rat gastric mucosal cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;360:273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leung AM, Redlak MJ, Miller TA. Oxygen radical induced gastric mucosal cell death: apoptosis or necrosis? Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2429–2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li J, Hou N, Faried A, Tsutsumi S, Kuwano H. Inhibition of autophagy augments 5‐fluorouracil chemotherapy in human colon cancer in vitro and in vivo model. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1900–1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li J, Hou N, Faried A, Tsutsumi S, Takeuchi T, Kuwano H. Inhibition of autophagy by 3‐MA enhances the effect of 5‐FU‐induced apoptosis in colon cancer cells. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:761–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liggett JL, Zhang X, Eling TE, Baek SJ. Anti‐tumor activity of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs: cyclooxygenase‐independent targets. Cancer Lett. 2014;346:217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lim SC, Han SI. Ursodeoxycholic acid effectively kills drug‐resistant gastric cancer cells through induction of autophagic death. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:1261–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu WJ, Shen TT, Chen RH, et al. Autophagy‐lysosome pathway in renal tubular epithelial cells is disrupted by advanced glycation end products in diabetic nephropathy. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:20499–20510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu YH, Zhang ZB, Zheng YF, et al. Gastroprotective effect of andrographolide sodium bisulfite against indomethacin‐induced gastric ulceration in rats. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015;26:384–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maity P, Bindu S, Choubey V, et al. Lansoprazole protects and heals gastric mucosa from non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID)‐induced gastropathy by inhibiting mitochondrial as well as Fas‐mediated death pathways with concurrent induction of mucosal cell renewal. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14391–14401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maity P, Bindu S, Dey S, et al. Indomethacin, a non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug, develops gastropathy by inducing reactive oxygen species‐mediated mitochondrial pathology and associated apoptosis in gastric mucosa: a novel role of mitochondrial aconitase oxidation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:3058–3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Maiuri MC, Kroemer G. Autophagy in stress and disease. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:365–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self‐eating and self‐killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mandayam S, Huang R, Tarnawski AS, Chiou SK. Roles of survivin isoforms in the chemopreventive actions of NSAIDS on colon cancer cells. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1109–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marciniak SJ, Ron D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in disease. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1133–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3:542–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mustafa SB, Olson MS. Expression of nitric‐oxide synthase in rat Kupffer cells is regulated by cAMP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5073–5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Narabayashi K, Ito Y, Eid N, et al. Indomethacin suppresses LAMP‐2 expression and induces lipophagy and lipoapoptosis in rat enterocytes via the ER stress pathway. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:541–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nishida Y, Arakawa S, Fujitani K, et al. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7‐independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature. 2009;461:654–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ogata M, Hino S, Saito A, et al. Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9220–9231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ojha R, Ishaq M, Singh S. Caspase‐mediated crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis: mutual adjustment or matter of dominance. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;11:514–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Piotrowski J, Slomiany A, Slomiany BL. Activation of apoptotic caspase‐3 and nitric oxide synthase‐2 in gastric mucosal injury induced by indomethacin. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Podvigina TT, Bogdanov AI, Filaretova LP. Healing of gastric mucosal erosions induced by indomethacin and restoration of glucocorticoids levels in the blood of rats. Patol Fiziol Eksp Ter. 2002;(2):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rainsford KD. Azapropazone: 20 Years Of Clinical Use. Netherlands: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sabiu S, Garuba T, Sunmonu T, et al. Indomethacin‐induced gastric ulceration in rats: protective roles of Spondias mombin and Ficus exasperata. Toxicol Rep. 2015;2:261–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sabiu S, Garuba T, Sunmonu TO, Sulyman AO, Ismail NO. Indomethacin‐induced gastric ulceration in rats: ameliorative roles of Spondias mombin and Ficus exasperata. Pharm Biol. 2016;54:180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Salvesen GS. Caspases and apoptosis. Essays Biochem. 2002;38:9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sawaguchi A, McDonald KL, Forte JG. High‐pressure freezing of isolated gastric glands provides new insight into the fine structure and subcellular localization of H+/K+‐ATPase in gastric parietal cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52:77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shalini S, Kumar S. Caspase‐2 and the oxidative stress response. Mol Cell Oncol. 2015;2:e1004956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shibata M‐A, Ambati J, Shibata E, Yoshidome K, Harada‐Shiba M. Mammary cancer gene therapy targeting lymphangiogenesis: VEGF‐C siRNA and soluble VEGF receptor‐2, a splicing variant. Med Mol Morphol. 2012;45:179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Slomiany BL, Piotrowski J, Slomiany A. Induction of tumor necrosis factor‐alpha and apoptosis in gastric mucosal injury by indomethacin: effect of omeprazole and ebrotidine. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:638–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Slomiany BL, Piotrowski J, Slomiany A. Role of caspase‐3 and nitric oxide synthase‐2 in gastric mucosal injury induced by indomethacin: effect of sucralfate. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1999;50:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Solier S, Pommier Y. The apoptotic ring: a novel entity with phosphorylated histones H2AX and H2B and activated DNA damage response kinases. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1853–1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Suvarna SK, Layton C, Bancroft JD. Bancroft's Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques, Expert Consult: Online and Print, 7: Bancroft's Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Suzuki H, Osawa T, Fujioka Y, Noda NN. Structural biology of the core autophagy machinery. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2017;43:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Takeuchi K, Takehara K, Ohuchi T. Diethyldithiocarbamate, a superoxide dismutase inhibitor, reduces indomethacin‐induced gastric lesions in rats. Digestion. 1996;57:201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vallecillo‐Hernández J, Barrachina MD, Ortiz‐Masiá D, et al. Indomethacin disrupts autophagic flux by inducing lysosomal dysfunction in gastric cancer cells and increases their sensitivity to cytotoxic drugs. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wu Y‐T, Tan H‐L, Shui G, et al. Dual role of 3‐methyladenine in modulation of autophagy via different temporal patterns of inhibition on class I and III phosphoinositide 3‐kinase. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10850–10861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Xu MY, Lee DH, Joo EJ, Son KH, Kim YS. Akebia saponin PA induces autophagic and apoptotic cell death in AGS human gastric cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;59:703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yamamoto K, Kamata O, Kato Y. Differential effects of anti‐inflammatory agents on lysosomal cysteine proteinases cathepsins B and H from rat spleen. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1984;35:253–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Yu C, Li W‐B, Liu J‐B, Lu J‐W, Feng J‐F. Autophagy: novel applications of nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for primary cancer. Cancer Med. 2017;7:471–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zhang S, Wang C, Tang S, et al. Inhibition of autophagy promotes caspase‐mediated apoptosis by tunicamycin in HepG2 cells. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2014;24:654–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhivotovsky B. Caspases: the enzymes of death. Essays Biochem. 2003;39:25–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhou XM, Wong BC, Fan XM, et al. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs induce apoptosis in gastric cancer cells through up‐regulation of bax and bak. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1393–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]