Abstract

Introduction

This study explored the role of body image dissatisfaction on orgasmic response during partnered sex and masturbation and on sexual relationship satisfaction. The study also described typologies of women having different levels of body image satisfaction.

Methods

A sample of 257 Norwegian women responded to an online survey assessing body image dissatisfaction, problems with orgasm, and sexual relationship satisfaction. Using structural equation modeling and factor mixture modeling, the relationship between body image dissatisfaction and orgasmic response was assessed, and clusters of sexual response characteristics associated with varying levels of body image dissatisfaction were identified.

Main Outcome Measure

Orgasmic function during partnered sex and masturbation, along with sexual relationship satisfaction, were assessed as a function of body image.

Results

Body image dissatisfaction, along with a number of covariates, predicted higher levels of “problems with orgasm” during both partnered sex and masturbation, with no significant difference in the association depending on the type of sexual activity. Varying levels of body image dissatisfaction/satisfaction were associated with differences in orgasmic incidence, difficulty, and pleasure during partnered sex; with one orgasmic parameter during masturbation; and with sexual relationship satisfaction.

Conclusion

Body image dissatisfaction and likely concomitant psychological distress are related to impaired orgasmic response during both partnered sex and masturbation and may diminish sexual relationship satisfaction. Women with high body image dissatisfaction can be characterized by specific sexual response patterns.

Horvath Z, Smith BH, Sal D, et al. Body Image, Orgasmic Response, and Sexual Relationship Satisfaction: Understanding Relationships and Establishing Typologies Based on Body Image Satisfaction. Sex Med 2020;8:740–751.

Key Words: Body Image, Sexual Relationship, Orgasm, Women, Masturbation, Partnered Sex

Introduction

Orgasmic difficulty (OD) is one of the more common sexual problems experienced by women, with about half of such women reporting distress about their condition.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 Interestingly, those women reporting greater distress about their OD are not necessarily those reporting greater OD. Rather, distress is more strongly linked to women's perceived causes for their OD: those women attributing their OD to psychological factors such as general anxiety or stress, sex-specific/performance anxiety, and cognitive distractibility report higher OD-related distress.8 Thus, compared with non-distressed OD counterparts, distressed women see their OD problem as emanating primarily from themselves. In doing so, they internalize the OD problem, take blame for it, and feel guilt, shame, self-anger, and distress about it.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 One potentially significant source of sex-specific/performance anxiety and distress is that of negative body image, a construct regarding a person's subjective opinion about his/her bodily appearance.16, 17, 18, 19

Link Between Body Image and Sexual Problems

For women, a positive body image has been associated with a more pleasurable sex life,20 whereas a negative body image is commonly mentioned as a factor contributing to OD.7 The relationship between body image and sexual functioning is partly independent of actual body size or mass (eg, body mass index), suggesting that subjective body image has more influence on a woman's overall and sexual functioning than her actual body dimensions.17,20, 21, 22

The burden of a negative body image on sexual response may be mediated through such factors as low self-esteem and psychological well-being,18,23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 and the specific framework through which negative body image leads to sexual problems has been conceptualized through self-objectification theory.30, 31, 32 Specifically, women are socialized to view themselves as objects to be looked at. Internalization of such ideation results in self-consciousness and “spectatoring” (observing oneself from a third person perspective33), especially in situations where the woman's body is exposed to others' evaluations, for example, during sexual activity.34 Women's focus on their own bodies may distract their attention from the positive sensations of sexual intimacy and the partner's erotic cues, which in turn may lead to diminished sexual self-efficacy and pleasure.34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 This relationship may be moderated by body shame, resulting from women's constant comparisons of themselves with cultural ideals,30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 and may motivate them to reduce these negative feelings by avoiding sexual activity altogether. As such, negative body image may become self-perpetuating—reducing sexual interest, a sense of intimacy with a partner, and sexual responsivity.39, 40, 41, 42, 43

Connections Between Negative Body Image and Partnered Sex vs Masturbation

A positive body image and higher self-acceptance of one's physical appearance have been associated with better sexual functioning, including orgasmic response, during partnered sex.7,43 Body dissatisfaction, on the other hand, presumably induces psychological distress, lower arousal and desire, and diminished orgasmic response and pleasure during partnered sex.7 Indeed, the sense that both partners are enjoying the sexual act strongly contributes to sexual dyadic mutuality and pleasure,7,44 which may be easily eroded by negative feelings and anxiety about one's body appearance.45 Although poor body image may diminish sexual response during partnered sex, its relationship to sexual/orgasmic response during masturbation is less understood. Specifically, negative body image may affect orgasmic capacity primarily through an anxiety-evoking evaluative process that operates primarily during partnered sex.46 Thus, negative body image could have different effects on orgasmic response, depending on whether masturbation or partnered sex is involved.11 To date, several studies have indicated that masturbation tends to be associated with a more positive body image, the idea being that women who masturbate are more able to associate sexual pleasure with their bodily responses and, in doing so, develop greater satisfaction with their bodies.47,48 However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined the relationship between body image dissatisfaction and orgasmic response and pleasure during masturbation, comparing it directly with orgasmic response and pleasure during partnered sex, in a multivariate context that includes other sexual and relationship parameters.

Body Image Dissatisfaction and Relationship Quality

The connection between negative body image and orgasmic problems (eg, diminished pleasure or frequency, increased OD) can both influence and be influenced by a woman's relationship status and quality.49,50 On the one hand, the distress and spectatoring/distraction related to negative body image51,52 can interfere with emotional closeness, leading to diminished intimacy and therefore to diminished relationship quality.45,46 On the other hand, high relationship satisfaction may help protect against the negative effects of negative body image on sexual functioning.43,44,51,52 Furthermore, positive body image and self-esteem appear to buffer the negative effects of a conflicted relationship.23,53 Thus, greater body dissatisfaction can lead to diminished relationship satisfaction and, vice versa, the perception that her partner is dissatisfied with her body may lead to lower sexual relationship satisfaction for both the woman and her partner.

Rationale and Aims

This study explored 5 in-depth questions related to body image satisfaction and sexual response. How is body image (dis)satisfaction related to sexual/orgasmic response (i) during partnered sex and (ii) during masturbation? (iii) Does body image satisfaction have a greater effect on orgasmic response during partnered sex than during masturbation? (iv) How is body image satisfaction related to sexual relationship satisfaction? Finally, given that body image satisfaction—as a broad construct that moderates perceptions of both the self and others—can have a pivotal role on multiple factors impinging on sexual and relationship functioning, we asked, (v) can typologies be constructed that identify a constellation of sexuality-related factors associated with varying levels of body image satisfaction in women? We approached our analyses with several expectations based on the research literature, including the assumptions that body image dissatisfaction would be more strongly related to partnered sex than to masturbation and that poor body image would relate negatively to sexual relationship satisfaction.

Materials and methods

Participants and Procedures

This cross-sectional study recruited a convenience sample of 354 Norwegian women through social media to participate in an online survey examining sexual health and sexual problems in women. The invitation to participate was posted on Facebook. To meet the aims of this study, women who had no sexual partner or who did not engage in sex with their partner (N = 66) or who did not masturbate (N = 31) were excluded from the analyses, resulting in a final sample of 257 women. Mean and median ages were 29.4 (SD = 8.66; range 18–69 years) and 28.0 years (interquartile range = 28–35 years), respectively. Regarding education, 88 women had completed high school (34.9%), 41 had completed a technical or training degree/certification (16.3%), and 123 had completed a college or postgraduate degree (48.8%). Furthermore, 220 participants self-identified as heterosexual (85.6%), 31 as bisexual (12.1%), 1 as homosexual (0.4%), and 5 as other (2.0%).

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the authors’ universities. To begin the online questionnaire, participants had to provide informed consent, confirm their age of 18 years or older, and acknowledge the voluntary and anonymous nature of the study. Because some questions asked about very intimate behaviors, participants were informed of the option to terminate participation or skip questions without any consequences. Participants were also given the option of contacting the principal investigator for further information.

Measures

The online questionnaire, constructed in Qualtrics, consisted of 2 parts and took approximately 20–25 minutes.

Questionnaire for Measuring Female Sexual Response

A 42-item questionnaire, which included demographic information, 13 (approximations) of the 19 questions on the Female Sexual Function Index,54,∗ and a number of experimenter-constructed items specific to the aims of the study, assessed various aspects of sexual and orgasmic response during partnered sex and masturbation. The questionnaire was translated to Norwegian using the standard 2-step (forward and back) process by independent translators.55 Outcome measures and relevant covariates were drawn from questionnaire items and are delineated in the next sections. Detailed descriptions of the questionnaire are provided elsewhere.11,50,56, 57, 58

Primary Covariate and Organizing Variable

Body Image Satisfaction

On a separate 4-item questionnaire, participants self-rated their satisfaction with their body image,59 with each item assessed on a 6-point scale (1 = does not apply at all, 6 = applies exactly). This instrument, first used on a large sample of Norwegian adolescents59 and subsequently used in a number of studies on body image (dis)satisfaction, has demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency among both adolescents and adults (α = 0.82-0.91).59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64 The 4 items measured women's satisfaction with their (i) appearance and (ii) body, and women's tendency to want to change their (iii) body and (iv) appearance (scores on the latter 2 items were reversed). Higher scores represented higher levels of body image satisfaction. A high level of internal consistency was found for the scale in the current analysis (ω = 0.90).

Outcome Measures

For the first 2 outcome measures, 3 single-item questions were used to establish 2 separate composite variables: “problems with orgasm” for masturbation and (separately) for partnered sex. The first single-item question for each composite outcome variable measured the percent of time reaching orgasm (%orgasmic frequency) during partnered sex and masturbation: “Estimate how often sexual activity with your (current or most recent) partner ends in (or ended in) orgasm?” and “Estimate how often masturbation (alone, without your partner present) ends in orgasm for you?” with tick marks at 10-point intervals on an analog scale, 1 = Never, 10 = Always. The second item for each composite outcome variable assessed levels of OD during partnered sex and masturbation: “When you have (or have had) sex with your partner, do (or did) you have problems reaching orgasm?” and “If you masturbate (alone, without a partner present), do you ever have problems reaching orgasm?”; scale: 1 = Almost never [having difficulty to reach orgasm], 5 = Almost always;, 6 = I don't reach orgasm. The third item for each composite outcome variable assessed lack of orgasmic pleasure during partnered sex and masturbation: “When you have (or have had) sex with a partner, how pleasurable or satisfying would you rate your typical orgasm?” and “If you masturbate (alone, without a partner present), how pleasurable or satisfying would you rate your typical orgasm?”; scale reversed for analyses: 1 = Very satisfactory, 5 = Very unsatisfactory, 6 = I don't reach orgasm. Composite scores for “problems with orgasm” during partnered sex (ω = 0.84) and during masturbation (ω = 0.76) presented satisfactory levels of internal consistency among the 3 measures.

The third outcome variable—sexual relationship satisfaction—was assessed with a single-item question: “How satisfied are you with your primary sexual relationship, that is, with the relationship you consider to be most significant to you?” measured on a 5-point scale: 1 = Not at all satisfied, 5 = Very satisfied.

Covariates Measuring Sexual Response

Several measures of sexual response were included as covariates or validating variables. Single-item questions with 8 response categories were used to assess frequencies of partnered sex: “Considering your sexual history with your current or most recent ongoing partner, how often do you (or did you) have sex with your partner?” and (separately) for masturbation, “How often do you masturbate?” during the past 9–12 months (2 = Almost never, 9 = One or more times daily). Participants also evaluated the overall importance of sex in their life during the past 9–12 months: “Please rate the importance of sex in your life?” scale: 1 = Not important at all, 5 = Very important.

Data Analysis

All analyses were performed with Mplus 8.0 statistical software.56 To address the 5 aims of the study, both variable- (aims 1–4) and person- (aim 5) centered analyses were performed.

Body image satisfaction—the primary predictor and organizing variable—was used (i) as a predictor variable for the composite outcome variables “problem with orgasm during masturbation” and “problems with orgasm during partnered sex” (aims 1–3), as well as for the outcome variable “sexual relationship satisfaction” (aim 4) and (ii) for establishing latent classes (typologies) of women of varying levels of body image satisfaction (aim 5).

Variable-Centered Analysis

Structural equation modeling (SEM)65 was used to describe the relationship between body image satisfaction and “problems with orgasm” during partnered sex (aim 1) and (separately) during masturbation (aim 2). It also compared the effects of body image on “problems with orgasm” during masturbation vs during partnered sex (aim 3) and, separately, identified the relationship between body image satisfaction and sexual relationship satisfaction (aim 4). In the SEM model, the effects of age, frequency of partnered sex and (separately) masturbation, and overall importance of sex were also included as covariates in the analyses.

For these analyses, observed indicators of OD, lack of orgasmic pleasure during partnered sex and masturbation, and observed items of body image satisfaction scale were specified as ordered categorical variables, with the aforementioned statistical models estimated by using the “weighted least squares with means and variances” adjusted method.

Person-centered analysis

This analysis attempted to identify sexuality-related variables associated with subgroups having varying levels of body image satisfaction (aim 5). Specifically, factor mixture modeling66,67 was performed to differentiate subgroups of participants with discrete levels of body image satisfaction. In this procedure, the estimated models simultaneously incorporate characteristics of a confirmatory factor analytic measurement model and mixture modeling (eg, latent class analysis). Therefore, the estimated models contained both a continuous latent variable (ie, body image satisfaction) and a categorical latent variable (ie, subgroups with different levels of body image satisfaction). In this model, factor loadings on the continuous latent variable of body image satisfaction were equal across the identified latent classes, whereas the identified latent cases differed in the mean of the continuous latent body image factor.

A step-by-step process was used to specify the number of subgroups: (i) first, the model with the optimal number of latent classes was selected; (ii) then, interpretation of the identified latent classes was carried out based on their profile characteristics; and (iii) the identified latent classes were validated and compared in terms of relevant covariates.68 An iterative model estimation process was used, such that models with increasing numbers of latent classes were estimated and compared on various indices to determine the optimal number of subgroups. In essence, these procedures ensured a sufficient number of clusters (typologies) so as to adequately discriminate among women based on their body image satisfaction, while also limiting the number of clusters so that they were not so highly specified as to become meaningless because of inordinate detail.

Results

Preliminary Bivariate Associations

As a preliminary step to understanding interrelationships among the predictor and outcome variables and to construct valid composite outcome variables for SEM analysis, bivariate associations were calculated to assess the strength and direction of relationships between body image satisfaction and specific measures of orgasmic response during (i) partnered sex and (ii) masturbation and (iii) sexual relationship satisfaction (Table 1). The estimated model presented optimal level of model fitness (χ222 = 24.360; P = .329; root mean square error of approximation = 0.020; comparative fit index = 1.000; Tucker-Lewis index = 0.999).

Table 1.

Correlation coefficients measuring associations between latent factor of satisfaction with body image and observed indicators of orgasmic responses during partnered sex and masturbation and sexual relationship satisfaction

| Covariate | Correlation with satisfaction with body image factor |

|---|---|

| Frequency of orgasm during partnered sex | 0.18† |

| Orgasmic difficulty during partnered sex | −0.15∗ |

| Lack of orgasmic pleasure during partnered sex | −0.21† |

| Frequency of orgasm during masturbation | 0.16∗ |

| Orgasmic difficulty during masturbation | −0.12 |

| Lack of orgasmic pleasure during masturbation | −0.25‡ |

| Sexual relationship satisfaction | 0.21† |

N = 257.

Significant correlation coefficients are indicated by P < .05.

Significant correlation coefficients are indicated by P < .01.

Significant correlation coefficients are indicated by P < .001.

Specifically, body image satisfaction presented significant, positive (though weak) relationships with %frequency of orgasm during partnered sex and (separately) masturbation and with sexual relationship satisfaction (r = 0.16–0.21). Moreover, significant, negative, and weak links were demonstrated between body image satisfaction and OD during partnered sex and lack of orgasmic pleasure during both partnered sex and masturbation (r = −0.25 to −0.15).

Variable-Centered Analysis Using SEM (Aims 1–4)

To assess the interrelationships among variables within a unified analysis, SEM examined the predictive effects of body image satisfaction on (i) each of the 2 composite outcome variables of “problems with orgasm” during (separately) partnered sex and masturbation and (ii) sexual relationship satisfaction. Satisfactory level of model fitness was observed (χ266 = 84.740; P = .060; root mean square error of approximation = 0.033; comparative fit index = 0.996; Tucker-Lewis index = 0.994). Bivariate correlation estimates between the predictor and outcome variables are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

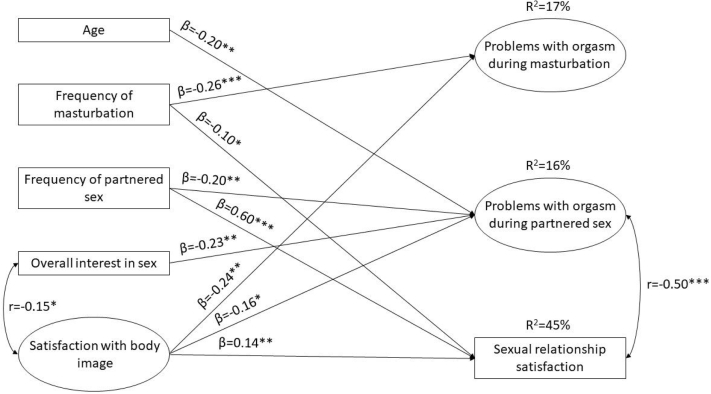

Standardized regression coefficients representing the predictive effects of body image satisfaction on the 2 composite outcome variables “problems with orgasm during partnered sex” and “problems with orgasm during masturbation” and the third outcome variable, sexual relationship satisfaction, are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. During partnered sex (aim 1), higher “problems with orgasm” was significantly associated with lower body image satisfaction, as well as with lower age, lower frequency of partnered sex, and lower overall interest in sex. During masturbation (aim 2), higher “problems with orgasm” was significantly associated with lower body image satisfaction and lower frequency of masturbation. The path coefficients between body image satisfaction and problems with orgasm during partnered sex (95% confidence interval of β = −0.31, −0.02) and problems with orgasm during masturbation (95% confidence interval of β = −0.39, −0.09) did not differ significantly in terms of strength (Wald test of parameter equality constraints = 0.502; P = .479), indicating that body image satisfaction played equally strong roles on orgasmic response, independent of whether the activity involved masturbation or partnered sex (aim 3).

Table 2.

Predictive effects on outcome variables measuring “problems with orgasm” during partnered sex and masturbation and on sexual relationship satisfaction

| Covariate | Outcome variables |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Problems with orgasm during partnered sex β (SE) | Problems with orgasm during masturbation β (SE) | Sexual relationship satisfaction β (SE) | |

| Age | −0.20 (0.06)† | −0.09 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.06) |

| Frequency of partnered sex | −0.20 (0.06)† | −0.01 (0.07) | 0.60 (0.05)‡ |

| Frequency of masturbation | 0.09 (0.07) | −0.26 (0.07)‡ | −0.10 (0.05)∗ |

| Overall interest in sex | −0.23 (0.07)† | −0.12 (0.08) | 0.11 (0.06) |

| Satisfaction with body image | −0.16 (0.07)∗ | −0.24 (0.08)† | 0.14 (0.06)† |

| Explained variance (R2) | 16% | 17% | 45% |

N = 257.

Significant standardized regression coefficients (β; and standard error values in parenthesis) are indicated by P < .05.

Significant standardized regression coefficients (and standard error values in parenthesis) are indicated by P < .01.

Significant standardized regression coefficients (and standard error values in parenthesis) are indicated by P < .001.

Figure 1.

Significant predictive effects on outcome variables measuring “problems with orgasm” during partnered sex and masturbation, and sexual relationship satisfaction. Note. N = 257. Single-ended arrows are standardized regression coefficients (β), whereas double-ended arrows represent correlations (r) between variables. Only significant (P < .05) indices are presented in the figure. Significant estimates are indicated by ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. Variables presented in ellipses are specified as latent variables, while variables presented in rectanguls are observed variables. R2 values indicate the level of explained variance on each outcome variables.

Regarding the outcome variable, sexual relationship satisfaction (aim 4), significant and positive predictive effects were presented for body image satisfaction as well as with frequency of partnered sex. The significant link between frequency of masturbation and sexual relationship satisfaction was considered a possible statistical artifact (ie, suppressor effect due to frequency of partnered sex) as the bivariate relationship between the 2 variables was non-significant.

Person-Centered Analysis Using Factor Mixture Modeling (Aim 5)

Person-centered analysis was aimed at identifying sexual response variables associated with subgroups of women having varying levels of body image satisfaction. This process involved 3 steps: model selection, characterizing each of the identified subgroups, and validation of the identified subgroups.

Model Selection

Models with 1 to 5 latent classes were estimated and contrasted. Model fit indices (Supplementary Table 2) suggested that optimal fit was presented for a model with 5 latent classes (subgroups). However, inclusion of the fifth latent class over 4 subgroups did not indicate a more parsimonious and optimal classification solution. Therefore, the 4-class solution was selected, with average probabilities of being assigned to each of the 4 classes being 0.95, 0.93, 0.95, and 0.97, indicating a very low error rate of class assignment.

Profile Characteristics of the Identified Latent Classes

Table 3 displays profile characteristics of the 4 identified latent classes. Women assigned to class 1 (“very low body image satisfaction”; N = 63; 24.71%) were characterized by very low levels of body image satisfaction. Women assigned to class 2 (“average body image satisfaction”; N = 111; 43.53%) showed average levels of item scores on each of the indicators, typically reporting being somewhat satisfied with their body image. Women of class 3 (“moderately high body image satisfaction”; N = 62; 24.31%) demonstrated greater than average and high scores on each item of body image satisfaction. Finally, women in class 4 (“very high body image satisfaction”; N = 19; 7.45%) had very high mean item scores, indicating very high levels of body image satisfaction.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of the retrieved factor mixture model with 3 latent classes

| Covariate | λ (SE) | Very low body image satisfaction class N = 63 (24.71%) M (SE) | Average body image satisfaction class N = 111 (43.53%) M (SE) | Moderately high body image satisfaction class N = 62 (24.31%) M (SE) | Very high body image satisfaction class N = 19 (7.45%) M (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I would like to change a good deal about my body.∗ | 1.00 (0.00)† | 1.63 (0.17) | 2.87 (0.12) | 4.15 (0.16) | 5.68 (0.27) |

| 2. By and large, I am satisfied with my looks. | 2.67 (0.76)∗∗∗ | 1.43 (0.06) | 3.38 (0.06) | 4.92 (0.07) | 6.00 (0.00) |

| 3. I would like to change a good deal about my looks.∗ | 1.06 (0.11)∗∗∗ | 1.76 (0.17) | 3.14 (0.12) | 4.33 (0.15) | 5.89 (0.07) |

| 4. By and large, I am satisfied with my body. | 1.79 (0.32)∗∗∗ | 1.41 (0.07) | 3.03 (0.08) | 4.72 (0.10) | 5.89 (0.07) |

| Continuous latent factor mean | - | −4.19 (0.58) | −1.87 (0.27) | 0.00 (0.00)‡ | 3.29 (0.55) |

Each item of the scale was assessed on a 6-point scale (1 = does not apply at all, 6 = applies exactly).

Negatively worded items were recoded so that higher scores represented higher satisfaction with body image.

Factor loading of the first item was fixed at 1 to set the metric of the continuous latent factor. Significant factor loadings (λ; and standard error values in parenthesis) are indicated by ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001.

Continuous latent factor mean was fixed at 0 to set the metric of the latent factor.

Validation of the Latent Classes

The 4 identified classes above were compared in terms of variables measuring orgasmic responses during partnered sex and (separately) during masturbation and on sexual relationship satisfaction (Table 4). This procedure is important to understanding how the 4 classes differ in ways beyond just body image satisfaction, thus showing how responses to sexual response-related items differ across groups having different levels of body image satisfaction. 5 variables indicated in the following paragraph showed the greatest differentiation among groups established on the basis of body image satisfaction.

Table 4.

Comparison of the identified latent classes

| Covariate | Very low body image satisfaction class N = 63 (24.71%) M (SE) |

Average body image satisfaction class N = 111 (43.53%) M (SE) |

Moderately high body image satisfaction class N = 62 (24.31%) M (SE) |

Very high body image satisfaction class N = 19 (7.45%) M (SE) |

Overall Wald-test (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of orgasm during partnered sex | −0.33 (0.13)a | 0.03 (0.11)b | 0.12 (0.12)b,c | 0.50 (0.22)c | 13.07 (0.004) |

| Orgasmic difficulty during partnered sex | 0.25 (0.13)b | −0.05 (0.11)a,b | −0.04 (0.12)a,b | −0.40 (0.22)a | 7.51 (0.057) |

| Lack of orgasmic pleasure during partnered sex | 0.25 (0.14)b | 0.00 (0.11)a,b | −0.19 (0.12)a | −0.18 (0.21)a,b | 6.40 (0.094) |

| Frequency of orgasm during masturbation | −0.14 (0.16)a | −0.04 (0.11)a | 0.18 (0.10)a | 0.14 (0.15)a | 4.06 (0.256) |

| Orgasmic difficulty during masturbation | 0.08 (0.14)a | 0.04 (0.10)a | −0.16 (0.11)a | 0.06 (0.26)a | 2.38 (0.497) |

| Lack of orgasmic pleasure during masturbation | 0.32 (0.16)c | −0.02 (0.10)b,c | −0.14 (0.11)a,b | −0.45 (0.16)a | 12.72 (0.005) |

| Sexual relationship satisfaction | −0.31 (0.14)a | −0.04 (0.10)a,b | 0.27 (0.12)b | 0.32 (0.23)b | 12.43 (0.006) |

3-step Bolck-Croon-Hagenaars (BCH) method was used to compare the identified latent classes. In the cases of comparisons, means (standard errors in parenthesis) in the same row that do not share superscripts differ at P < .05 level. Each validating variable was standardized such that their means were equal to 0 and standard deviations equal to 1.

Orgasmic Frequency

Compared with the other 3 latent classes, members of class 1 (“very low body image satisfaction”) showed significantly lower frequency of orgasm during partnered sex. Women in class 4 (“very high body image satisfaction”) reported significantly higher frequency of orgasm during partnered sex than those assigned to class 2 (“average body image satisfaction”).

Orgasmic Difficulty

In terms of reaching orgasm during partnered sex, class 1(“very low body image satisfaction”) reported significantly higher rates of difficulty than class 4 (“very high body image satisfaction”).

Orgasmic Pleasure During Partnered Sex

Compared with women in class 3 (“moderately high body image satisfaction”), women in class 1 (“very low body image satisfaction”) experienced significantly lower levels of orgasmic pleasure during partnered sex.

Orgasmic Pleasure During Masturbation

Women in class 3 (“moderately high body image satisfaction”) and class 4 (“very high body image satisfaction”) presented significantly higher orgasmic pleasure during masturbation than those in class 1 (“very low body image satisfaction”). In this regard, women in class 2 (“average body image satisfaction”) also had lower rates of orgasmic pleasure during masturbation than women in class 4 (‘very high body image satisfaction’).

Sexual Relationship Satisfaction

Women in class 3 (“moderately high body image satisfaction”) and class 4 (“very high body image satisfaction”) demonstrated significantly higher levels of sexual relationship satisfaction than Class 1 women (“very low body image satisfaction”).

Discussion

This study confirms a potential role for body image on orgasmic response during partnered sex, and, to our knowledge, demonstrates for the first time that low body satisfaction is also associated with greater problems with orgasm during masturbation. It further reiterates the importance of body image satisfaction to overall sexual relationship satisfaction, and shows that varying levels of body image satisfaction are associated with clusters of other sexuality-related variables.

Predictors of Problems with Orgasm: Role of Body Image Dissatisfaction

Having a positive body image has been associated with a more pleasurable sex life19 and better sexual functioning during partnered sex.7,43 Body dissatisfaction, related to increased psychological distress, has been related to less frequent, pleasurable and consistent orgasm among women.7,8,69 Our results, using a standard measure for body image satisfaction,59 confirmed this pattern, indicating that lower body image satisfaction is associated with higher levels of “problems with orgasm,” a composite measure comprised of orgasmic difficulty, percent of time reaching orgasm, and diminished orgasmic pleasure. Other variables included in the SEM—age, frequency of partnered sex, and overall interest in sex—were also significant predictors of “problems with orgasm.” The fact that body image satisfaction was only weakly correlated with these other predictor variables in the SEM argues that the association of body image dissatisfaction with diminished orgasmic response occurs independently of these other factors. Both lower age and lower frequency of partnered sex—also predictive of greater “problems with orgasm”—likely stand as proxies for lower levels of partnered sexual experience. Better orgasmic response has been linked to both of these factors in previous research.7,11,57,70

Contrary to our expectation and that of self-objectification theory, lower body image satisfaction also significantly predicted greater “problems with orgasm” during masturbation. In fact, body image satisfaction played equally strong roles on orgasmic response, independent of whether the activity involved masturbation or partnered sex. Despite a dearth of studies relating body image to masturbation, several studies on the topic have generally emphasized the positive relationship between masturbation and body image, the idea being that masturbation may enhance bodily response, pleasure, a sense of control and well-being, and thus body satisfaction.47,48 However, neither of these studies examined the relationship specifically between body image satisfaction and orgasmic parameters during partnered sex and masturbation as our study did.

This finding is notable, as a major assumption underlying the relationship between body image satisfaction and sexual response (based on self-objectification theory31,32) has been that the evaluative component involved in partnered sex inhibits desire, arousal, and thus orgasmic response,19,21, 22, 23, 24,27,71,72 and consistent with this idea, prior research has suggested that masturbation may be instrumental in developing a more positive body image.47,48 Yet the current findings suggest that poor body image may affect orgasmic pleasure and response equally during both partnered sex and masturbation. That is, while partner evaluation may play a role in mediating the effects of body image satisfaction on orgasmic response during partnered sex, other factors must also be involved, as partner evaluation is absent during masturbation. Whether such factors are psychological (eg, overall low feelings of self-efficacy and esteem7,13,31,33,73) or physiological could not be addressed in our analysis. However, both might be operating. From a psychological perspective, women who struggle to reach orgasm under any circumstances may tend to internalize the problem, feel greater distress, and experience diminished feelings of overall sexual self-efficacy.7,8,13 During masturbation (even with no “evaluating observer” physically present), as women focus on their own bodies more intensely, some may be reminded of their shame and dissatisfaction, viewing themselves from an outside objectifying position (spectatoring). Furthermore, given that body image dissatisfaction is often associated with negative genital self-image, as women physically touch their own bodies, they may trigger negative thoughts concerning their appearance.74 Together, the combination of shame and spectatoring might well exacerbate cognitive distraction and disrupt attention to erotic sensations.73 As frequency of masturbation in our sample was not linked to the level body image (dis)satisfaction, the interpretation that women who engage in masturbation are more likely to struggle with a positive body image has less plausibility. In other words, women who masturbate more frequently do not appear to do so simply because they are avoiding partnered sex owing to low body image satisfaction. Finally, from a physiological perspective, women whose body image dissatisfaction is linked to being less-ideally figured, overweight, or obese may as well suffer lower sexual responsivity because of the physiological imbalances sometimes associated with these conditions.75

The fact that lower masturbation frequency was associated with greater “problems with orgasm” during masturbation is not surprising, although the relationship is likely bidirectional: women who masturbate less tend to be less proficient at it,57,58 and women who are less likely to reach orgasm under any conditions are less inclined to masturbate.58 On the other hand, the fact that neither age nor frequency of partnered sex was related to “problems with orgasm” during masturbation strengthens the argument made previously and that these variables stand as proxies for partnered sexual experience and thus would not be related to problems with orgasm during masturbation.

Predictors of Sexual Relationship Satisfaction: Role of Body Image Dissatisfaction

Consistent with our expectation, higher body image satisfaction was a significant predictor of higher sexual relationship satisfaction, consistent with other studies that have demonstrated such an association.45,51,52 Higher body image satisfaction likely leads to more comfortable (less distressful) sexual interactions with the partner, greater pleasure, and hence a more satisfying sexual relationship.7,8,49 At the same time, better relationship satisfaction may offer greater balance to the physical and emotional components of sexual intimacy, affording women some protection against negative self-evaluation/dissatisfaction regarding their body appearance.23,43,45,51, 52, 53

Other predictors of sexual relationship satisfaction included a higher frequency of partnered sex (a proxy often linked to this outcome) and lower frequency of masturbation. Previous analyses have shown that frequency and preference for masturbation among women are often tied to partner issues (ie, women who perceive the partner as uninterested or who feel less satisfied with partnered sex because of a lower incidence of orgasm) and therefore to lower sexual and overall relationship satisfaction.11,50,56

Typologies of Women With Varying Levels of Body Image Satisfaction

Also unique to this analysis, we were able to identify clusters of sexuality-related variables associated with low, average, moderately high, and very high body image satisfaction. Such typologies help give context to the pervasive role that body image has—through impairment or enhancement—on sexual and relationship functioning, functions sometimes considered among the important defining aspects of people's lives.

Women with very low body image satisfaction (class 1) tended to have a low incidence of orgasm during partnered sex, higher OD during partnered sex, and lower pleasure during partnered sex and masturbation and the lowest relationship satisfaction. This constellation of factors suggests a relatively high level of orgasmic problems during both partnered and masturbatory sex, coupled with very low sexual relationship satisfaction, a potential indicator of problems within the overall relationship.†

Women with very high and moderately high body image satisfaction (classes 4 and 3) both indicated the highest levels of sexual relationship satisfaction within the sample but differed somewhat in their orgasmic response. The former group (class 4: very high body image satisfaction) was the antithesis of very low body image satisfaction women described previously: these women reported the highest incidence of orgasm and the least orgasmic difficulty during partnered sex, along with moderately high levels of pleasure during partnered sex. They also indicated the highest level of orgasmic pleasure during masturbation. In contrast, the latter group (class 3: moderately high body image satisfaction), although also endorsing a high level of sexual relationship satisfaction, was characterized by a moderate incidence of orgasm during partnered sex, moderate orgasmic difficulty during partnered sex and masturbation yet moderately high orgasmic pleasure during both partnered sex and masturbation. These groups provide evidence for the idea that, even though some women experience moderate OD during partnered sex, they might still report moderately strong pleasure during partnered sex and masturbation and rate their sexual relationship satisfaction equivalent to those having the highest level of body image satisfaction. Such patterns perhaps reiterate the strong protective effects of high sexual relationship satisfaction on positive sexual response, even though body image may not be as positive.23,53

Those women with average body satisfaction (class 2) generally fell in the midrange on most variables, that is, better off than class 1 women but not reaching the levels of classes 3 and 4 women. Specifically, these women showed a higher incidence of orgasm and less OD during partnered sex than class 1 women, and they were situated between class 1 and class 3 or 4 women on orgasmic pleasure during partnered sex and masturbation. Their sexual relationship satisfaction also fell midway between class 1 and class 3 or 4 women. This midway pattern consistently characterized this group, although only some of the contrasts reached significance.

Overall, these typologies suggest that specific sexual response patterns are associated with varying levels of body image satisfaction. In this respect, body image satisfaction—and the constellation of responses associated with it—affords a window into the types of issues likely to affect, and be affected by, orgasmic capacity during partnered sex and masturbation. The finding that body image satisfaction, along with several other variables regarding interest in sex and frequency of partnered and masturbatory sex, explained nearly 17% of variance in “problems with orgasm” (of which an estimated 4–5% comes from body image) and 45% of variance in sexual relationship satisfaction argues for assessing and addressing such issues within the context of remediation and treatment.14,35,42,76

Strengths and Limitations

Our study included the benefits common to many online/non-online surveys,77 including a sizable sample drawn from Norway. Furthermore, anonymity afforded through an Internet approach reduces social desirability and improves openness in responding, so important when dealing with sensitive and private topics such as orgasm, pleasure, and masturbation.78,79 Finally, we investigated the role of body image satisfaction on orgasmic response and sexual relationship satisfaction in the context of empirically supported covariates reported in the research literature.

At the same time, our conclusions are limited by the sample size and the potential for systematic bias within the sample, a problem for any non-probability study that relies heavily on social media for recruitment. In addition, we used a fairly simple, 1-dimensional 4-item instrument for assessing body image dissatisfaction and selected single items from the Female Sexual Function Index to assess a number of sexual response constructs. We acknowledge that the use of a multidimensional instrument may have yielded more precise estimates for such constructs. Finally, owing to the cross-sectional nature of the study, although we could statistically control for relevant covariates, we could not assume causality when examining relationships between body image satisfaction, orgasmic response, and sexual relationship satisfaction. As such, it was not possible to consider the influence of unmeasured, third variables on the observed findings. For example, controlling for the effects of body mass index and measures of depressive, somatic, and eating disorder symptoms might have resulted in greater precision with respect to the associations between body image and sexual response. Longitudinal studies could address the aforementioned issues, as well as replication in community samples drawing participants from wider economic and age brackets that allow parsing out potential differences due to variables such as ethnicity, cultural background, and sociosexual orientation.

Statement of authorship

Zsolt Horvath: Writing - Original Draft, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition; Betina Hodt Smith: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing; Dorottya Sal: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing; Krisztina Hevesi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition; David L. Rowland: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Funding: Zsolt Horvath was supported by the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH-1157-8/2019-DT).

Clarifying wording changes were made for most questions based on consensus input during the survey development process from 3 focus groups of women [see 7,8,11]. Such changes were often necessary as FSFI items do not specifically query about situations involving masturbation.

Overall relationship satisfaction and sexual relationship satisfaction were correlated at 0.481, P < .001

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2020.06.008.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.McCool M.E., Zuelke A., Theurich M.A. Prevalence of female sexual dysfunction among premenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Sex Med Rev. 2016;4:197–212. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berman J.R., Berman L., Goldstein I. Female sexual dysfunction: incidence, pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment options. Urology. 1999;54:385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kontula O., Miettinen A. Determinants of female sexual orgasms. Socioaffective Neurosci Psychol. 2016;6:31624. doi: 10.3402/snp.v6.31624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis R.W., Fugl-Meyer K.S., Corona G. Definitions/epidemiology/risk factors for sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7(4pt2):1598–1607. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham C.A. The DSM diagnostic criteria for female orgasmic disorder. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:256–270. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9542-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rowland D.L., Kolba T.N. Understanding orgasmic difficulty in women. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1246–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hevesi K., Gergely Hevesi B., Kolb T.N. Self-reported reasons for having difficulty reaching orgasm during partnered sex: relation to orgasmic pleasure. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;4:106–115. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2019.1599857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hevesi K., Miklos E., Horvath Z.S. Typologies of women with orgasmic difficulty and their relationship to sexual distress. J Sex Med. 2020;17:1144–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peixoto M.M., Nobre P. Automatic thoughts during sexual activity, distressing sexual symptoms, and sexual orientation: findings from a web survey. J Sex Marital Ther. 2016;42:616–634. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2015.1113583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalmbach D.A., Pillai V., Kingsberg S.A. The transaction between depression and anxiety symptoms and sexual functioning: a prospective study of premenopausal, healthy women. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44:1635–1649. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0381-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowland D.L., Donarski A., Graves V. The experience of orgasmic pleasure during partnered and masturbatory sex in women with and without orgasmic difficulty. J Sex Marital Ther. 2019;45:550–561. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2019.1586021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loos V.E., Bridges C.F., Critelli J.W. Weiner’s attribution theory and female orgasmic consistency. J Sex Res. 1987;23:348–361. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rowland D.L., Adamski B.A., Neal C.J. Self-efficacy as a relevant construct in understanding sexual response and dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther. 2015;41:60–71. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2013.811453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephenson K.R., Meston C.M. Why is impaired sexual function distressing to women? The primacy of pleasure in female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2015;12:728–737. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kearney-Cooke A. Reclaiming the body: using guided imagery in the treatment of body image disturbance among bulimic women. In: Hornyak L.M., Baker E.K., editors. Experimental therapies for eating disorders. Guilford Press; New York: 1989. pp. 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiederman M. Women’s body image selfconsciousness during physical intimacy with a partner. J Sex Res. 2000;37:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamiya Y., Cash T.F., Thompson J.K. Sexual experiences among college women: the differential effects of general versus contextual body images on sexuality. Sex Roles. 2006;55:421–427. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crose R.G. A woman's aging body: Friend or foe? In: Trotman F.K., Brody C., editors. Psychotherapy and counseling with older women. Springer; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satinsky S., Reece M., Dennis B. An assessment of body appreciation and its relationship to sexual function in women. Body Image. 2012;9:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weaver A.D., Byers E.S. The relationships among body image, body mass index, exercise, and sexual functioning in heterosexual women. Psychol Women Q. 2006;30:333–339. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths S., Hay P., Mitchison D. Sex differences in the relationships between body dissatisfaction, quality of life and psychological distress. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2016;40:518–522. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowery S.E., Kurpius S.E.R., Befort C. Body image, self-esteem, and health-related behaviors among male and female first year college students. J Coll Student Dev. 2005;46:612–623. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faith M.S., Schare M.L. The role of body image in sexually avoidant behavior. Arch Sex Behav. 1993;22:345–356. doi: 10.1007/BF01542123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ackard D.M., Kearney-Cooke A., Peterson C.B. Effect of body image and self-image on women’s sexual behaviors. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:422–429. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200012)28:4<422::aid-eat10>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davison S., Bell R., LaChina M. Sexual function in well women: stratification by sexual satisfaction, hormone use, and menopause status. J Sex Med. 2008;5:1214–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koch P., Mansfield P., Thurau D. Feeling frumpy: the relationships between body image and sexual response changes in midlife women. J Sex Res. 2005;4:215–223. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez D.T., Kiefer A.K. Body concerns in and out of the bedroom: implications for sexual pleasure and problems. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36:808–820. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldsmith K.M., Byers E.S. Perceived impact of body feedback from romantic partners on young adults' body image and sexual well-being. Body Image. 2016;17:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hannier S., Baltus A., De Sutter P. The role of physical satisfaction in women’s sexual self-esteem. Sexologies. 2017;27:e85–e95. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartky S.L. Routledge; New York, NY: 1990. Femininity and domination: studies in the phenomenon of oppression. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Claudat K., Warren C.S. Self-objectification, body self-consciousness during sexual activities, and sexual satisfaction in college women. Body image. 2014;11:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grower P., Ward L.M. Examining the unique contribution of body appreciation to heterosexual women's sexual agency. Body Image. 2018;27:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cash T.F., Smolak L., editors. Body image: a handbook of science, practice, and prevention. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dove L., Wiederman M.W. Cognitive distraction and women's sexual functioning. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:67–78. doi: 10.1080/009262300278650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trapnell P.D., Meston C.M., Gorzalka B.B. Spectatoring and the relationship between body image and sexual experience: self-focus or self-valence? J Sex Res. 1997;34:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meana M., Nunnink S.E. Gender differences in the content of cognitive distraction during sex. J Sex Res. 2006;43:59–67. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva E., Pascoal P.M., Nobre P. Beliefs about appearance, cognitive distraction and sexual functioning in men and women: a mediation model based on cognitive theory. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1387–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts T.A., Gettman J.Y. Mere exposure: Gender differences in the negative effects of priming a state of self-objectification. Sex Roles. 2004;51:17–27. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quinn-Nilas C., Benson L., Milhausen R.R. The Relationship between body image and domains of sexual functioning among heterosexual, emerging adult women. Sex Med. 2016;4:e182–e189. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pujols Y., Meston C.M., Seal B.N. The association between sexual satisfaction and body image in women. J Sex Med. 2010;7:905–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seal B.N., Bradford A., Meston C.M. The association between body esteem and sexual desire among college women. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38:866–872. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9467-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.La Rocque C.L., Cioe J. An evaluation of the relationship between body image and sexual avoidance. J Sex Res. 2011;48:397–408. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.499522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallwiener S., Strohmaier J., Wallwiener L.M. Sexual function is correlated with body image and partnership quality in female university students. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1530–1538. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pascoal P.M., Narciso I.D.S.B., Pereira N.M. What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people's definitions. J Sex Res. 2014;51:22–30. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.815149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milhausen R.R., Robin R., Andrea C.B. Relationships between body image, body composition, sexual functioning, and sexual satisfaction among heterosexual young adults. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44:1621–1633. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowland D.L., van Lankveld J.D.M. Anxiety and performance in sex, sport,and stage: identifying common ground. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1615. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shulman J.L., Horne S.G. The use of self-pleasure: masturbation and body image among African American and European American Women. Psych Women Quart. 2003;27:262–269. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bowman C.P. Women’s masturbation: experiences of sexual Empowerment in a primarily sex-positive sample. Psych Women Quart. 2014;38:363–378. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Byers E.S. Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: a longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. J Sex Res. 2005;42:113–118. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rowland D.L., Sullivan S.L., Hevesi K. Orgasmic latency and related parameters in women during partnered and masturbatory sex. J Sex Med. 2018;15:1463–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Steer A., Tiggemann M. The role of self-objectification in women’s sexual functioning. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2008;27:205–225. [Google Scholar]

- 52.van den Brink F., Smeets M.A., Hessen D.J. Positive body image and sexual functioning in Dutch female university students: the role of adult romantic attachment. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;45:1217–1226. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0511-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Purdon C., Holdaway L. Non-erotic thoughts: content and relation to sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction. J Sex Res. 2006;43:154–162. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosen R., Brown C., Heiman J. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Beaton D.E., Bombardier C., Guillemin F. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rowland D.L., Hevesi K., Conway G.R. Relationship between masturbation and partnered sex in women: does the former facilitate, inhibit, or not affect the latter? J Sex Med. 2020;17:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rowland D.L., Kolba T.N. Relationship of specific sexual activities to orgasmic latency, pleasure, and difficulty during partnered sex. J Sex Med. 2019;16:559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rowland D.L., Kolba T.N., McNabney S.M. Why and how women masturbate, and the relationship to orgasmic response. J Sex Marital Ther. 2020:1–16. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2020.1717700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alsaker F.D. Pubertal timing, overweight, and psychological adjustment. J Early Adolescence. 1992;12:396–419. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holsen I., Kraft P., Røysamb E. The relationship between body image and depressed mood in adolescence: a 5-year longitudinal panel study. J Health Psych. 2001;6:613–627. doi: 10.1177/135910530100600601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bendixen M., Daveronis J., Kennair L.E.O. The effects of non-physical peer sexual harassment on high school students’ psychological well-being in Norway: consistent and stable findings across studies. Int J Pub Health. 2018;63:3–11. doi: 10.1007/s00038-017-1049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holsen I., Jones D.C., Birkeland M.S. Body image satisfaction among Norwegian adolescents and young adults: a longitudinal study of the influence of interpersonal relationships and BMI. Body image. 2012;9:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riiser K., Løndal K., Ommundsen Y. The outcomes of a 12-week Internet intervention aimed at improving fitness and health-related quality of life in overweight adolescents: the Young & Active controlled trial. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Birkeland M.S., Melkevik O., Holsen I. Trajectories of global self-esteem development during adolescence. J Adolescence. 2012;35:43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Loehlin J.C., Beaujean A.A. Taylor & Francis; Milton Pk, UK: 2016. Latent variable models: an introduction to factor, path, and structural equation analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Muthén B. Should substance use disorders be considered as categorical or dimensional? Addiction. 2006;101:6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muthén L.K. Muthén BO Mplus User’s Guide. Eighth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. 2017. https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf Available at:

- 68.Asparouhov T., Muthén B.O. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: using the BCH Method in Mplus to estimate a distal outcome model and an arbitrary secondary mode. 2014. https://www.statmodel.com/download/asparouhov_muthen_2014.pdf Available at:

- 69.Gillen M.M., Markey C.H. A review of research linking body image and sexual well-being. Body Image. 2019;31:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goldey K.L., Posh A.R., Bell S.N. Defining pleasure: a focus group study of solitary and partnered sexual pleasure in queer and heterosexual women. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45:2137–2154. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0704-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robbins A.R., Reissing E.D. Appearance dissatisfaction, body appreciation, and sexual health in women across adulthood. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47:703–714. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-0982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang S.R., Yang C.F., Chen K.H. Relationships between body image, sexual dysfunction, and health-related quality of life among middle-aged women: a cross-sectional study. Maturitas. 2019;126:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.04.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Comstock D.L., Hammer T.R., Strentzsch J. Relational-cultural theory: a framework for bridging relational, multicultural, and social justice competencies. J Couns Develop. 2008;86:2008. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Herbenick D., Schick V., Reece M. The Female Genital Self-Image Scale (FGSIS): results from a nationally representative probability sample of women in the United States. J Sex Med. 2011;8:158–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rowland D.L., McNabney S.M., Mann A.R. Sexual function, obesity, and weight loss in men and women. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5:323–338. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.ter Kuile M.M., Both S., van Lankveld J.J. Cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual dysfunctions in women. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:595–610. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Catania J.A., Dolcini M.M., Orellan R. Non-probability and probability-based sampling strategies in sexual science. J Sex Res. 2015;52:396–411. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1016476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Manzo A.N., Burke J.M. Increasing response rate in web-based/internet surveys. In: Gideon L., editor. Handbook of survey methodology for the social Sciences. Springer; New York: 2012. pp. 327–343. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ong A.D., Weiss D.J. The impact of anonymity on responses to sensitive questions. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30:1691–1708. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.