Abstract

Amiloride is a potassium retaining diuretic and natriuretic which acts by reversibly blocking luminal epithelial sodium channels (ENaCs) in the late distal tubule and collecting duct. Amiloride is indicated in oedematous states, and for potassium conservation adjunctive to thiazide or loop diuretics for hypertension, congestive heart failure and hepatic cirrhosis with ascites. Historical studies on its use in hypertension were poorly controlled and there is insufficient data on dose-response. It is clearly highly effective in combination with thiazide diuretics where it counteracts the adverse metabolic effects of the thiazides and its use in the Medical Research Council Trial of Older Hypertensive Patients, demonstrated convincing outcome benefits on stroke and coronary events. Recently it has been shown to be as effective as spironolactone in resistant hypertension but there is a real need to establish its potential role in the much larger number of patients with mild to moderate hypertension in whom there is a paucity of information with amiloride particularly across an extended dose range.

Keywords: Amiloride, hypertension, natriuretic, diuretic, review

Introduction

In 1965, Bickling and colleagues observed that certain nonsteroidal acylguanidine derivatives displayed both natriuretic and antikaliuretic properties. This led to the synthesis of amiloride.1 Amiloride hydrochloride (3,5-diamino-N-carbamimidoyl-6-chloropyrazine-2-carboxamide) is a synthetic pyrazine derivative. It is a potassium-sparing diuretic. It inhibits sodium reabsorption through epithelial sodium channels in the distal convoluted tubules and collecting ducts of the kidney. Currently, amiloride is indicated in oedematous states, and for potassium conservation adjunctive to thiazide or loop diuretics for hypertension, congestive heart failure and hepatic cirrhosis with ascites.2 Amiloride is currently being used increasingly in hypertension management yet it is an old drug and there is a paucity of information on its blood pressure effects across an extended dose range and in various subgroups of patients with hypertension. This review summarises a number of clinical trials investigating the effects of amiloride for its natriuretic and diuretic effects and for its effects on blood pressure (BP).

Basic pharmacology

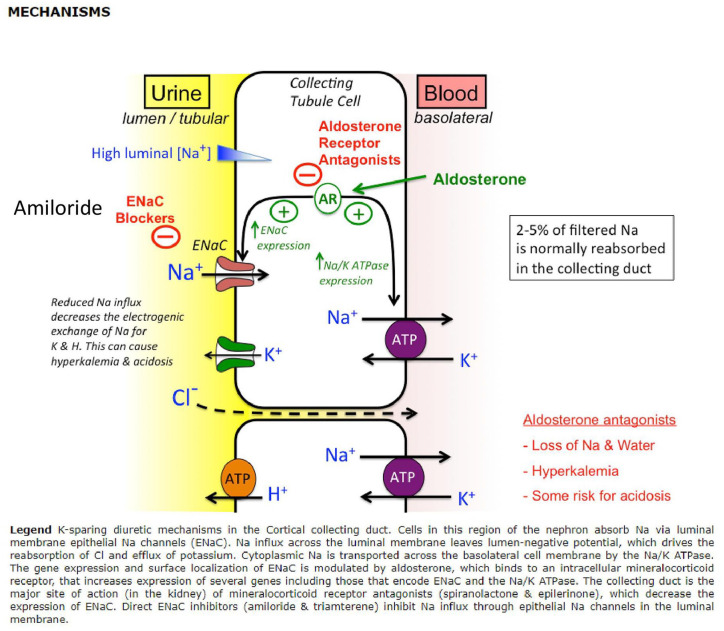

Amiloride is a pyrazine-carbonyl-guanidine derivative and it is chemically unrelated to other diuretics or antikaliuretic agents.3 It consists of a substituted pyrazine ring with an acylguanidine group attached to ring position 2, amino groups attached at ring positions 3 and 5, and a Cl group attached at position 6 (Figure 1). Due to the guanidium moiety, amiloride is a weak base with a pKa of 8.7 in aqueous solution. Protonation of amiloride occurs in the guanidine group and not in the amino groups. Due to these acid-base properties, amiloride can effectively penetrate biological and artificial membranes.4 Amiloride is rarely soluble in water.1

Figure 1.

Structure of amiloride.

Clinical pharmacology

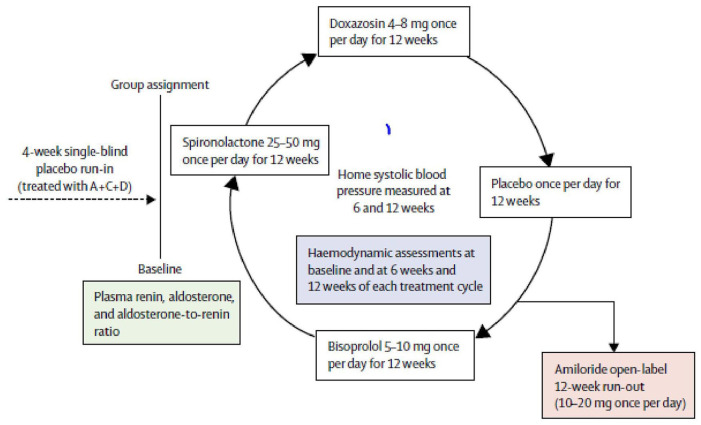

Amiloride reaches the nephron largely by glomerular filtration and acts on the luminal membrane of the distal convoluted tubule and collecting ducts3 (Figure 2). In the late distal tubules and collecting ducts, particularly in the cortical collecting tubules, there are principal cells which have epithelial sodium channels (ENaCs) in their luminal membranes. ENaC is a heterotrimer consisting of three subunits – alpha, beta and gamma. ‘Maximal sodium permeability is induced when all three subunits are coexpressed in the same cell’.5,6 In Liddle’s syndrome, mutations in the ENaC result in hyperactivity leading to severe hypertension. ENaCs are a highly regulated site for sodium reabsorption and sodium enters the cell by passive diffusion down the electrochemical gradient created by the basolateral Na+/K+ pump.5,7 The high sodium permeability depolarises the luminal but not the basolateral membrane. This creates a lumen-negative transepithelial potential difference. The transepithelial potential difference provides a driving force for potassium secretion into the lumen through the apical potassium channels.5 Amiloride can reversibly block luminal ENaCs of the principal cells by binding to the channel pore. There is a limited capacity for the late distal tubule and collecting duct to reabsorb solutes, therefore inhibition of the sodium channel at this site only mildly increases Na+and Cl- excretion rates.5 The inhibition of ENaC hyperpolarises the luminal membrane, reducing the lumen-negative transepithelial voltage. Normally, the lumen-negative potential difference facilitates cation secretion, its attenuation then decreases K+, H+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ excretion rates.3,5,6

Figure 2.

Reproduced TMed Web diuretic_pharm [TUSOM I Pharmwiki].

Pharmacokinetics

A 1973 trial8 studying the kinetics and bioavailability of amiloride (single dose of 20 mg) found that peak serum concentrations were reached at 4 h post amiloride administration, with an average of 47.5 ng/mL (±13.8). Approximately half of an oral dose of amiloride can be recovered in the urine as unmetabolised drug.3 The remainder of the unmetabolised drug can be recovered in the stool. In this study peak serum levels were reached at 3 h with a half-life of 6 h. Amiloride had extensive extravascular distribution as demonstrated by its volume of distribution.

A further study1 suggested that a single oral dose of 20 mg amiloride had a biological half-life of 9.6 ± 1.8 h in humans. Its effects began approximately 2 h post drug administration and peak activity was reached within 4–8 h.

A trial by Sabanathan et al.9 examined the effects of ageing and hypertension on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a combination capsule of atenolol (50 mg), hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg) and amiloride (2.5 mg). Three patient groups with a total of 18 volunteers participated – a group of young healthy subjects, a group of elderly healthy subjects, and a group of elderly hypertensive patients. Hypertension did not affect the pharmacokinetics of any drugs. However, a significant fall in BP was observed in the hypertensive group. Ageing significantly increased the bioavailability and the 24-h plasma concentration in all three drugs. The half-life of amiloride was also significantly longer in the elderly. Chronic dosing of amiloride increased the 24-h plasma concentration in all patient groups. There were no significant differences in the urinary recovery of amiloride between the young and elderly on acute or chronic dosing.

Current knowledge indicates that amiloride is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and has an oral bioavailability of around 50%. Co-administration with food can decrease absorption to 30%, but the absorption rate is unchanged. After administration, the onset of diuretic activity usually occurs within 2 h. Peak diuresis occurs within 6–10 h. The diuretic effects persist for about 24 h post administration. Amiloride is not metabolised by the liver. Approximately 50% is excreted unchanged by the kidneys in the urine, around 40% is excreted in the faeces. In patients with normal renal function, amiloride has a serum half-life of 6–9 h.10–13

Dose-response to diuretic and natriuretic effects

The dose-response of amiloride was investigated in six healthy male subjects aged between 21 and 30.14 Each subject received oral amiloride in doses of 5, 10, 20, 30, 40 and 60 mg. In addition, to determine the period of maximum amiloride activity, a single oral dose of 40 mg of amiloride was given to six more healthy males. Control and experimental urine samples were collected hourly throughout the day. The results demonstrated that by increasing the dose from 5 to 40 mg, the effects produced also increased. This includes increases in urinary volume, sodium and chloride excretion, and reduced potassium loss. However, above 40 mg, the responses reached a plateau. Some of these effects persisted for more than 10 h after drug administration. However, this effect was more prominent in doses above 30 mg. For a single dose of 40 mg, the response began in the second hour, reaching a maximum between 4 and 6 h and declined thereafter. At around 9 h post amiloride administration, the reduction in potassium secretion decreased to control values. Both sodium and chloride excretion effects persisted beyond 10 h. Urinary bicarbonate excretion was also increased by the 40 mg oral dose.

In a second study,15 the dose-response was investigated in 14 subjects. Amiloride was given orally, once or twice daily, in dosages ranging from 1 mg/day to 30 mg/twice daily. For single-day administration of doses varying from 1 mg to 20 mg, 1 mg was able to produce a slight natriuresis. Between 4 and 20 mg, natriuresis and potassium retention took place but with little diuresis. A more prolonged administration of amiloride was also examined in two normal subjects and a cirrhotic patient. A total of 20 mg/day of amiloride was administered for 2–4 days and similar changes were seen. The magnitude of the daily effects declined by the fourth day. Withdrawal of therapy caused a rebound in sodium retention and potassium secretion. In another six patients, 20 mg/day of amiloride was administered for 5–12 days. There were more pronounced potassium retention and mild hyperchloremic acidosis. In one hypertensive patient in whom the dose was maintained for a further 2 weeks, there was a slow return of potassium and bicarbonate to control values. An amiloride dose of 20 mg or more daily was maintained for 3–5 months in a hypertensive patient with idiopathic oedema, clinical effectiveness was maintained with no adverse effects.

In a 1981 review, Vidt3 concluded that by increasing the dose from 5 to 40 mg, a greater diuretic and natriuretic response was observed. However, a plateau occurred above 40 mg. The onset of action occurred within 2 h and the maximal effect occurred between 4 and 6 h. At lower doses, these effects were present for the first 10 h after administration. At doses above 40 mg, these effects may be prolonged up to 24 h.

There are no clear records of studies of a dose-effect relation between increasing doses of amiloride and placebo-controlled BP responses.

Adverse effects

The most dangerous adverse effect of amiloride is hyperkalaemia due to its potassium-sparing effects.3 Therefore, amiloride is contraindicated in patients with hyperkalaemia, and those at increased risk of developing hyperkalaemia. This includes patients with renal failure, and those receiving other K+-sparing diuretics or potassium supplements. Care should be exercised in patients taking angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers. NSAIDs can also increase the likelihood of hyperkalaemia in patients receiving sodium channel blockers. Amiloride has also been associated with side effects on the central nervous, gastrointestinal, endocrine, musculoskeletal, dermatological and haematological systems. The most common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and headache.5,11 Chronic amiloride treatment may also increase serum uric acid concentrations due to increased reabsorption in the proximal tubule.3,5

Clinical trials in hypertension

Early trials (pre-2000)

Paterson et al.16 in 1968 conducted a clinical trial to compare the effect of amiloride hydrochloride with hydrochlorothiazide in 12 previously untreated mild hypertensives. Each patient was treated with amiloride 5 mg three times daily, hydrochlorothiazide 50 mg daily or a combination of both for three 6-week periods. All three treatments lowered BP by approximately 24/12 mmHg, although there was no placebo control. Hypotensive effects were not significantly increased with the two treatments combined, however, two patients withdrew on the combination due to excessive diuresis. When the two agents were combined, serum potassium was maintained near pre-treatment levels whereas thiazide alone led to hypokalaemia and amiloride alone caused a slight increase in plasma potassium. The study included too few patients, however, to determine differential BP responses in the three groups of patients.

In a study by Kremer et al.,17 amiloride (40 mg/day) was given to 19 patients with primary hyperaldosteronism. Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) fell by 29/15 mmHg but again there was no placebo control. There were reductions in total exchangeable sodium, and in serum sodium and bicarbonate; while total exchangeable potassium, total body potassium, serum potassium, chloride and urea, and plasma renin, angiotensin II and aldosterone all increased significantly. Falls of a smaller magnitude (12/9 mmHg) were observed in five patients with essential hypertension; hyperkalaemia was not observed.

A multicentre study conducted in 198118 compared amiloride 5–10 mg, amiloride 5–10 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 50–100 mg and hydrochlorothiazide 50–100 mg in 179 patients (aged between 21 and 69 years) with mild to moderate essential hypertension for 12 weeks. Significant BP reduction (amiloride 14/8 mmHg; amiloride plus hydrochlorothiazide 23/11 mmHg; hydrochlorothiazide 20/10 mmHg) was seen in all three treatment groups. This study clearly shows the complementarity of combining amiloride with a thiazide, but the monotherapy comparisons reflect low doses of amiloride compared with high doses of hydrochlorothiazide.

Thomas and Thomson19 investigated the biochemical disturbance produced by thiazide diuretics and its potential reversal by amiloride in patients with moderate hypertension. In previously untreated patients, the thiazide produced a significant fall in plasma potassium and hyperuricaemia that did not occur with amiloride. Patients receiving long term treatment for their hypertension who continued to take thiazides had persistent hypokalaemia and hyperuricaemia, whereas substitution with amiloride corrected the hypokalaemia and serum uric acid returned towards normal ranges. Patients receiving long term treatment also had impaired glucose tolerance, which was corrected in those receiving amiloride. Control of hypertension was equally effective with both preparations (metoprolol and thiazide 45/31 mmHg; metoprolol and amiloride 44/32 mmHg; continued thiazide 7/8 mmHg; substituted amiloride 11/10 mmHg), but the dose of amiloride was only 5–10 mg daily.

Svendsen et al.20 investigated the effects of amiloride in thiazide-treated hypertensive patients. A total of 28 patients with essential hypertension, 12 men and 16 women aged between 26 and 71, were initially treated with hydrochlorothiazide (1 mg/kg body weight, median 75 mg/day) for 8 weeks. Patients were then randomly assigned to continue hydrochlorothiazide therapy (12 patients, same dosage) or to receive adjunctive amiloride treatment (16 patients, 5 mg/25 mg hydrochlorothiazide, median 15 mg/day) for the following 3 months. In the adjunctive amiloride treatment group, both plasma potassium and total body potassium increased by 15% and 4% respectively. The addition of amiloride induced an activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS) system, a significant rise was seen in the plasma concentrations of renin, angiotensin II and aldosterone. There was a significant decrease in standing SBP in the hydrochlorothiazide and amiloride group, however, standing DBP and supine BP did not change. The antihypertensive effect of amiloride could be antagonised by this stimulation of the RAAS. The increase in aldosterone secretion could also limit the potassium-retaining ability of amiloride.

Backhouse et al.21 compared the efficacy and tolerability of frusemide plus amiloride and hydrochlorothiazide plus amiloride in patients with mild to moderate hypertension. Thirty six patients were included in the study, age ranging between 40 and 68 years. Eighteen patients were treated with frusemide 40 mg and amiloride 5 mg, the other 18 were given hydrochlorothiazide 50 mg and amiloride 5 mg, both groups took one tablet daily for 2 weeks. Both treatments were found to reduce BP effectively in the majority of patients, 13/18 patients in the furosemide/amiloride group and 14/18 patients in the hydrochlorothiazide/amiloride group showed a ‘good response’ (mean supine DBP <90 mmHg or decreased by 10 mmHg). There was a significant decrease in the mean potassium and sodium levels in the hydrochlorothiazide/amiloride group, this was not seen in the frusemide/amiloride group.

One of the most important studies with amiloride and the only one in which longer term follow up was designed to obtain morbidity and mortality data was the Medical Research Council Trial of Hypertension in Older Patients.22

The trial was designed to establish whether lowering BP in elderly hypertensive patients reduced cardiovascular outcomes, notably stroke and myocardial infarction. In this trial of around 4000 patients, BP was lowered with a combination of hydrochlorothiazide and amiloride or atenolol and compared with placebo.

Follow up was for an average of 5.8 years. BP was lowered more effectively by the diuretic combination, although in some patients the beta-blocker was added to control BP (15/6 mmHg compared with placebo). Both stroke and coronary events were reduced significantly by thiazide/amiloride (31% and 44%, respectively). In this trial, only relatively low doses of amiloride (2.5 mg) were used in combination with hydrochlorothiazide (25 mg).

Later trials (2000–2010)

Pratt et al.23 investigated the BP responses to amiloride and spironolactone in normotensive subjects. The authors hypothesised that secondary hyperaldosteronism as a response to the decreased sodium reabsorption caused by amiloride may reduce its usefulness to lower BP. Therefore, they tested the BP response in 40 normotensive subjects using amiloride 5 mg/day, spironolactone 25 mg/day, the combination of amiloride 5 mg/day and spironolactone 25 mg/day or placebo. Over 4 weeks, the combination of amiloride and spironolactone lowered SBP by 4.6 ± 1.6 (mean ± SEM) mmHg and DBP by 2.2 ± 1.2 mmHg. However, either drug alone had no significant effect on BP. Thus, the authors speculated that the combination of drugs was complimentary, resulting in overall greater inhibition of ENaC function than either drug used alone. It was also suggested that the significant decline in BP provides additional support for the importance of ENaC in regulating BP.

Baker et al.24 conducted a trial to investigate the effectiveness of amiloride in the treatment of hypertension in people of African origin with T594M polymorphism. The T594M polymorphism of ENaC is found in ~5% of people of African origin and is significantly associated with high BP. The T594M polymorphism leads to high BP by disrupting negative regulation of ENaC and increasing sodium channel activity similar to that seen in Liddle’s syndrome. Since amiloride can control BP in Liddle’s syndrome, the authors investigated whether amiloride would also control BP in subjects of African origin with T594M polymorphism. The study showed that amiloride 20 mg was able to control the BP of these subjects as effectively as taking two or more other antihypertensive agents.

A study conducted by Pratt et al.25 used amiloride to investigate the racial difference in the activity of ENaC since it is known that people with black ethnic origin appear to retain more sodium which suppresses the secretion of renin and aldosterone, compared to those of white ethnic origin. Therefore, ENaC activity could either be higher in black ethnic groups leading to sodium retention or lower due to reduced stimulation by aldosterone. To examine differences in ENaC activity between the two ethnic groups, 5 mg/day amiloride for 1 week was used to inhibit ENaC in 20 black and 25 white normotensive young subjects. BP and measurements of potassium were used for comparison. The study found that amiloride reduced BP in the white ethnic group but not in those with black ethnic origin. This is consistent with less ENaC activity to inhibit in the blacks. Serum potassium concentration was higher in blacks than whites, also consistent with lower ENaC activity in blacks. The authors suggested that in those with black ethnic origin, there was an increase in sodium retention at other sites that suppressed aldosterone levels, resulting in fewer ENaCs at the cell surface.

In 2008, Guerrero et al.26 published a study which investigated the efficacy of amiloride and enalapril as second option antihypertensive drugs in patients with uncontrolled BP receiving hydrochlorothiazide (HCT) treatment. Eighty two patients (18–75 years of age) treated with hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/day for at least 4 weeks, with uncontrolled BP, participated in this randomised, double-blind clinical trial. Patients were randomised to receive enalapril (10 mg/day) or amiloride (2.5 mg/day) during a follow-up period of 12 weeks. If in the fourth week, office BP was not controlled, the doses were doubled (enalapril to 20 mg and amiloride to 5 mg). If office BP was still uncontrolled in the eighth week, propranolol 40 mg BID was added. Both ABPM and office BP were used for the analysis. Overall 43.2% of the patients in the amiloride group had controlled office BP compared to 75% of the patients in the enalapril group at the end of the follow-up period. HCT-amiloride reduced office BP by 16.4 ± 12.3/5.8 ± 12.7 mmHg and HCT-enalapril by 22.2 ± 15.8/9.7 ± 9.4 mmHg. In addition, more patients in the HCT-amiloride group doubled the amiloride dose or needed to use propranolol. ABPM in both groups had a similar circadian pattern. There was a significant increase in serum potassium levels in both groups and a significant increase in triglycerides in the HCT-amiloride group. Cough was more frequent in participants treated with enalapril. The authors concluded that enalapril was more effective than amiloride as an add-on drug in patients taking hydrochlorothiazide with uncontrolled BP.

Recent trials (2010–2020)

In 2012, Matthesen et al.27 tested the effect of amiloride and spironolactone on renal tubular function, ambulatory blood pressure (ABP) and pulse wave velocity (PWV) during baseline conditions and after furosemide bolus in healthy participants in a double-blinded, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Eleven Caucasian males and 13 Caucasian females participated in the trial with a mean age of 22 years and BMI of 23 ± 3 kg/m2. Mean BP was 119/73 ± 9/10 mmHg. Participants were given amiloride 5 mg twice daily, spironolactone 25 mg twice daily, or placebo twice daily for three periods of 28 days. Examinations were done both at baseline conditions and after furosemide 40 mg intravenous bolus. There were no differences in 24-h ABP, PWV, renal tubular function or plasma concentration of vasoactive hormones in baseline conditions in the treatment groups. Urinary output (UO) and CH2O (tubular function) were not significantly different after 4 weeks of placebo, amiloride and spironolactone treatment. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion were the same at the end of all three treatments. Thus, amiloride and spironolactone did not change the cardiovascular and renal effect variables. However, furosemide increased UO, CH2O, and urinary sodium and potassium output. Water absorption via AQP2 and sodium absorption via ENaC were also increased simultaneously. Furosemide induced a more pronounced increase in PWV, CSBP, plasma concentrations of angiotensin II and aldosterone after amiloride and spironolactone treatment compared to placebo.

In 2014, Bhagatwala et al.28 evaluated the effects of amiloride monotherapy on BP and cardiovascular risk in young (18–35 years), drug naïve adults with prehypertension (120–139/80–89 mmHg). The participants took 10 mg daily amiloride in the morning with breakfast for 4 weeks, in a non placebo-controlled, open-label study. After 4 weeks of amiloride monotherapy, there were significant reductions in peripheral SBP (7.06 ± 2.25 mmHg), peripheral DBP (4.35 ± 1.67 mmHg), central SBP (7.68 ± 2.56 mmHg) and central DBP (4.49 ± 1.78 mmHg). No changes in heart rate and weight were observed. The reductions in peripheral and central BPs did not differ between Caucasians and African Americans. There was a significant increase in FMD (brachial artery flow-mediated dilation, a biomarker of nitric oxide dependent vasodilation and endothelial function) and a significant reduction in CR-PWV (carotid radial pulse wave velocity, a surrogate marker of arterial stiffness). There were no significant changes in CF-PWV (carotid femoral pulse wave velocity) and AI%HR75 (augmentation index adjusted for heart rate at 75). There was an increase in serum aldosterone concentration. The rise in the plasma renin activity (PRA) was insignificant. Aldosterone-renin ratio, serum potassium concentration and serum creatinine concentration were all significantly elevated. Participants with stage 2 prehypertension (130–139/85–89 mmHg, n = 6) had significantly greater mean reductions in peripheral SBP (14.5 ± 4.60 mmHg, p < 0.01) and central SBP (16.15 ± 5.44 mmHg, p < 0.01), compared with participants with stage 1 prehypertension (120–129/80–84 mmHg, n = 11). Improvements in CF-PWV and AI%HR75 were also greater. The major findings in this study include amiloride decreased peripheral and central BPs; amiloride improved endothelial function and lowered peripheral arterial stiffness; amiloride mediated improvements in FMD and PWV may be independent of its BP-lowering effects, and amiloride monotherapy increased serum aldosterone. The differences in observations between stage 2 and stage 1 prehypertension led the authors to propose that amiloride might be more efficacious when BP is higher in drug naïve young adults. The improvements in endothelial function led to the proposition that amiloride improves FMD and PWV by blocking vascular ENaC. The authors concluded that amiloride could be used as an early intervention to halt the progression to hypertension and cardiovascular disease in young adults with prehypertension.

The PATHWAY-3 trial conducted by Brown et al.29 was a parallel-group, randomised, double-blind trial which compared the effects of hydrochlorothiazide and amiloride, either alone or in combinations, on glucose tolerance and BP. The trial included patients aged 18–80 years, with clinic SBP 140 mmHg or higher, home SBP 130 mmHg or higher, an indication for diuretic treatment, and at least one component of the metabolic syndrome in addition to hypertension. Patients were randomly assigned to 24 weeks of daily oral treatment with starting doses of 10 mg amiloride, 25 mg hydrochlorothiazide or 5 mg amiloride plus 12.5 mg hydrochlorothiazide. All doses were doubled after 12 weeks. An OGTT (oral glucose tolerance test) was done at baseline, 12 weeks and 24 weeks. Seated home and clinic BP were measured for each patient for the duration of the trial. The primary outcome, assessed on a modified intention-to-treat basis, was the change in plasma glucose concentration 2 h after oral administration of 75 g glucose drink from baseline at 12 and 24 weeks. The main secondary outcome was the change in home SBP from baseline at 12 and 24 weeks. The modified intention-to-treat analysis included 132 patients in the amiloride group, 134 patients in the hydrochlorothiazide group and 133 patients in the amiloride plus hydrochlorothiazide group. 2 h glucose concentrations after OGTT, averaged at 12 and 24 weeks, were significantly lower in the amiloride group than in the hydrochlorothiazide group (difference from hydrochlorothiazide: −0.55 mmol/L, p = 0.0093) and in the combination group compared to the hydrochlorothiazide group (difference from hydrochlorothiazide: −0.42 mmol/L, p = 0.048). The mean reduction in home SBP during 24 weeks between the amiloride and hydrochlorothiazide groups did not differ significantly (12.9 mmHg and 12.2 mmHg, respectively). However, the reduction in BP in the combination group was significantly greater than that in the hydrochlorothiazide group. The mean rise in renin concentration at 12 and 24 weeks in the combination group was 1.69 times higher than in the hydrochlorothiazide group. Plasma potassium was unchanged in the combination group, but a significant dose-dependent rise in concentration was seen in the amiloride group (by 0.63 mmol/L at 24 weeks) and a significant fall was seen in the hydrochlorothiazide group (by 0.27 mmol/L at 24 weeks). Seven patients (4.8%) in the amiloride group and three patients (2.3%) in the combination group reported hyperkalaemia. Thirteen serious adverse events occurred but the frequency did not differ significantly between the groups. The trial demonstrated that after 24 weeks of treatment, a potassium-sparing diuretic reduced BP as efficaciously as high-dose thiazide without inducing adverse effects on blood glucose concentrations. A combination of half the conventional doses of amiloride and hydrochlorothiazide was not associated with increased 2 h glucose concentrations compared with hydrochlorothiazide treatment alone, instead, significantly larger reductions in BP was observed compared to full doses of either diuretic given alone. Amiloride monotherapy did not cause clinically significant hyperkalaemia, amiloride combined with hydrochlorothiazide did not affect potassium concentrations significantly either. Based on these results, the authors recommended that the combination of amiloride and hydrochlorothiazide in doses equipotent for BP reduction becomes the first-choice diuretic in patients in whom adequate diuretic has not yet been prescribed.

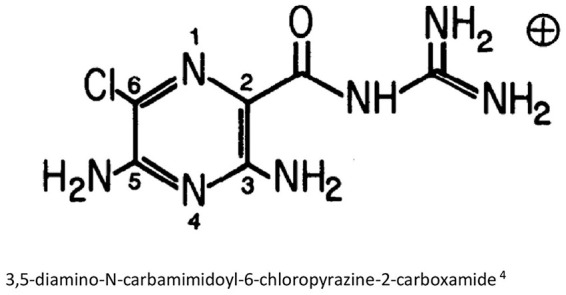

PATHWAY-230 was a randomised, double-blind crossover trial done at 14 UK primary and secondary care sites in 314 patients with resistant hypertension. Patients were given 12 weeks of once daily treatment with each of placebo, spironolactone 25–50 mg, bisoprolol 5–10 mg and doxazosin 4–8 mg and the change in home SBP was assessed as the primary outcome. In a substudy of this trial, the effect of amiloride 10–20 mg once daily on clinic SBP was assessed during an optional 6–12 week open-label runout phase (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic for PATHWAY 2 trial.30

Amiloride (10 mg once daily) reduced clinic SBP by 20.4 mmHg (95% CI 18.3–22.5), compared with a reduction of 18.3 mmHg (16.2–20.5) with spironolactone (25 mg once daily). No serious adverse events were recorded. Mean plasma potassium concentrations increased from 4.02 mmol/L (95% CI 3.95–4.08) on placebo to 4.50 (4.44–4.57) on amiloride (p < 0.0001).

Ydegaard et al.31 investigated the relationship between the BP-lowering effect of amiloride and endothelial ENaC and eNOS (endothelial nitric oxide synthase). Nitric oxide (NO) products and cGMP (cyclic guanosine monophosphate) were measured in the urine and plasma samples of diabetic patients before and after amiloride treatment (20–40 mg for 2 days: plasma n = 22, urine n = 12; 5–10 mg for 8 weeks: plasma n = 52, urine n = 55). Treatment with high dose oral amiloride (20–40 mg/day) for 2 days in type 1 diabetes patients with or without nephropathy lowered systolic and diastolic arterial pressure significantly (7.5 ± 2.4/4.3 ± 1.8 mmHg). Plasma and urine NO-products increased significantly. The decrease in BP was not significantly related to the increase in plasma or urine NO-products. Plasma cGMP decreased in response to amiloride while urine cGMP was unchanged. Plasma NO-product concentration directly correlated with urinary NO-product concentration significantly after amiloride treatment. This correlation was not observed before treatment. There were no significant relations between NO-products and cGMP in urine and plasma. Eight weeks of treatment with low dose amiloride (5–10 mg/day) in type 2 diabetes patients with treatment-resistant hypertension significantly lowered average daytime arterial BP by 6.3/3.0 mmHg, night-time BP by 7.1/2.8 mmHg and 24-h BP by 6.1/3.6 mmHg. There were no changes in plasma or urine NO-products and cGMP. The authors found that the BP decline in patients did not relate to NO-products or cGMP. The researchers concluded that the antihypertensive effect of ENaC blockers is primarily due to an effect on renal epithelial but not endothelial ENaC-eNOS interaction.

Summary

Amiloride has been studied in a number of trials since its discovery, often as an adjunctive treatment for hydrochlorothiazide or furosemide. Where amiloride monotherapy was administered, the trials generally consisted of a small number of subjects, of normotensives or prehypertensives, or of patients of African origin with specific polymorphisms.

Amiloride has dose-dependent diuretic effects up to 40 mg, although there is little data following higher doses. In normotensive subjects there is minimal BP reduction but reductions in excess of 15 mmHg SBP are seen with higher doses (20–40 mg) – comparable to those reported with spironolactone. There are few if any placebo-controlled trials evaluating the dose-response of amiloride with respect to BP. Efficacy is increased when amiloride is combined with a thiazide and with this combination, as demonstrated in the PATHWAY-3 Trial,29 the adverse metabolic effects of thiazide can be prevented. In the long-term trial of amiloride/hydrochlorothiazide, cardiovascular outcomes were improved in elderly hypertensive patients.22

In the hypertensive population BP remains poorly controlled and inappropriate use of drugs and dosage contributes to this ongoing problem. Diuretics play an important part of treatment algorithms.32 It is regrettable that we have very few studies on amiloride alone in dose-escalating studies that are placebo-controlled. It is evident that better BP control can be achieved when amiloride is combined with thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics. Further consideration might be given to the use of amiloride earlier in treatment strategies, perhaps even in mild hypertension, particularly if first choice agents are ineffective or poorly tolerated, but higher doses (up to 20–40 mg) than those used conventionally should be encouraged in patients with normal renal function.

There is an increasing recognition that potassium-sparing diuretics have a role in many patients with ‘essential’ hypertension, where the potential for hyperaldosteronism is significant. The drugs also are increasingly effective in the elderly, where the majority of the hypertensive population are found. Early studies with newer mineralocorticoid antagonists, which share the efficacy of spironolactone but avoid the steroidogenic side effects are promising. To date, however, their use has been confined to heart failure (finerenone)33 or of restricted geographical distribution (esaxerenone).34

Further trials in hypertension are to be encouraged.

Acknowledgments

PS is supported by the Biomedical Research Centre Award to Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Peter Sever  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0421-2409

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0421-2409

References

- 1. Benos DJ. Amiloride: a molecular probe of sodium transport in tissues and cells. Am J Physiol 1982; 242(3): C131–C145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. British National Formulary - NICE, 2020. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/

- 3. Vidt DG. Mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, adverse effects, and therapeutic uses of amiloride hydrochloride, a new potassium-sparing diuretic. Pharmacotherapy 1981; 1(3): 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garty H, Benos DJ. Characteristics and regulatory mechanisms of the amiloride-blockable Na+ channel. Physiol Rev 1988; 68(2): 309–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brunton LL, Hilal-Dandan R, Knollmann BC. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Almajid AN, Cassagnol M. Amiloride. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing, 2020. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31194443 (accessed 10 June 2020). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kleyman TR, Cragoe EJ., Jr. Amiloride and its analogs as tools in the study of ion transport. J Membr Biol 1988; 105(1): 1–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith AJ, Smith RN. Kinetics and bioavailability of two formulations of amiloride in man. Br J Pharmacol 1973; 48(4): 646–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sabanathan K, Castleden CM, Adam HK, et al. A comparative study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of atenolol, hydrochlorothiazide and amiloride in normal young and elderly subjects and elderly hypertensive patients. Euro J Clin Pharmacol 1987; 32(1): 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amiloride Hydrochloride, Monograph for Professionals. Drugs.com. https://www.drugs.com/monograph/amiloride-hydrochloride.html#ra (2019, accessed 11 July 2020).

- 11. Amiloride 5 mg Tablets BP - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). emc. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/6020/smpc#PHARMACOKINETIC_PROPS (2016, accessed 11 July 2020).

- 12. Midamor, (amiloride) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more https://reference.medscape.com/drug/midamor-amiloride-342406 (accessed 11 July 2020).

- 13. Amiloride Hydrochloride, Drug Summary. Prescriber’s Digital Reference. https://www.pdr.net/drug-summary/amiloride-hydrochloride?druglabelid=1840 (accessed 11 July 2020).

- 14. Baba WI, Lant AF, Smith AJ, et al. Pharmacological effects in animals and normal human subjects of the diuretic amiloride hydrochloride (MK-870). Clin Pharmacol Ther 1968; 9(3): 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bull MB, Laragh JH. Amiloride. A potassium-sparing natriuretic agent. Circulation 1968; 37(1): 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paterson JW, Dollery CT, Haslam RM. Amiloride hydrochloride in hypertensive patients. Br Med J 1968; 1(5589): 422–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kremer D, Boddy K, Brown JJ, et al. Amiloride in the treatment of primary hyperaldosteronism and essential hypertension. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1977; 7(2): 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Multicentre Diuretic Cooperative Study Group. Multiclinic comparison of amiloride, hydrochlorothiazide, and hydrochlorothiazide plus amiloride in essential hypertension. Arch Intern Med 1981; 141(4): 482–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thomas JP, Thomson WH. Comparison of thiazides and amiloride in treatment of moderate hypertension. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983; 286(6383): 2015–2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Svendsen UG, Ibsen H, Rasmussen S, et al. Effects of amiloride on plasma and total body potassium, blood pressure, and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in thiazide-treated hypertensive patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1983; 34(4): 448–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Backhouse CI, Platt J, Crawford RJ, et al. An open study to compare the efficacy and tolerability of two diuretic combinations, frusemide plus amiloride and hydrochlorothiazide plus amiloride, in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension. Curr Med Res Opin 1988; 10(10): 690–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. MRC Working Party. Medical Research Council trial of treatment of hypertension in older adults: principal results. BMJ 1992; 304(6824): 405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pratt JH, Eckert GJ, Newman S, et al. Blood pressure responses to small doses of amiloride and spironolactone in normotensive subjects. Hypertension 2001; 38(5): 1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baker EH, Duggal A, Dong Y, et al. Amiloride, a specific drug for hypertension in black people with T594M variant? Hypertension 2002; 40(1): 13–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pratt JH, Ambrosius WT, Agarwal R, et al. Racial difference in the activity of the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel. Hypertension 2002; 40(6): 903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guerrero P, Fuchs FD, Moreira LM, et al. Blood pressure-lowering efficacy of amiloride versus enalapril as add-on drugs in patients with uncontrolled blood pressure receiving hydrochlorothiazide. Clin Exp Hypertens 2008; 30(7): 553–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matthesen SK, Larsen T, Lauridsen TG, et al. Effect of amiloride and spironolactone on renal tubular function, ambulatory blood pressure, and pulse wave velocity in healthy participants in a double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Clin Exp Hypertens 2012; 34(8): 588–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bhagatwala J, Harris RA, Parikh SJ, et al. Epithelial sodium channel inhibition by amiloride on blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk in young prehypertensives. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2014; 16(1): 47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brown MJ, Williams B, Morant SV, et al. Effect of amiloride, or amiloride plus hydrochlorothiazide, versus hydrochlorothiazide on glucose tolerance and blood pressure (PATHWAY-3): a parallel-group, double-blind randomised phase 4 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2016; 4(2): 136–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Williams B, Macdonald TM, Morant S, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet 2015; 386(10008): 2059–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ydegaard R, Andersen H, Oxlund CS, et al. The acute blood pressure-lowering effect of amiloride is independent of endothelial ENaC and eNOS in humans and mice. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2019; 225(1): e13189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG136], 28 August 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136 (accessed 12 September 2020).

- 33. Pei H, Wang W, Zhao D, et al. The use of a novel non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist finerenone for the treatment of chronic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97(16): e0254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ito S, Itoh H, Rakugi H, et al. Double-blind randomized phase 3 study comparing esaxerenone (CS-3150) and eplerenone in patients with essential hypertension (ESAX-HTN Study). Hypertension 2020; 75(1): 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]