Abstract

Background

Lockdowns were implemented to limit the spread of COVID-19. Peritraumatic distress (PD) and post-traumatic stress disorder have been reported after traumatic events, but the specific effect of the pandemic is not well known.

Aim

The aim of this study was to assess PD in France, a country where COVID-19 had such a dramatic impact that it required a country-wide lockdown.

Methods

We recruited patients in four groups of chatbot users followed for breast cancer, asthma, depression and migraine. We used the Psychological Distress Inventory (PDI), a validated scale to measure PD during traumatic events, and correlated PD risk with patients’ characteristics in order to better identify the ones who were the most at risk.

Results

The study included 1771 participants. 91.25% (n=1616) were female with a mean age of 32.8 (13.71) years and 7.96% (n=141) were male with a mean age of 28.0 (8.14) years. In total, 38.06% (n=674) of the respondents had psychological distress (PDI ≥14). An analysis of variance showed that unemployment and depression were significantly associated with a higher PDI score. Patients using their smartphones or computers for more than 1 hour a day also had a higher PDI score (p=0.026).

Conclusion

Prevalence of PD in at-risk patients is high. These patients are also at an increased risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder. Specific steps should be implemented to monitor and prevent PD through dedicated mental health policies if we want to limit the public health impact of COVID-19 in time.

Trial registration number

Keywords: psychological trauma, mental health, stress disorders, post-traumatic

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic called for unprecedented policies by governments around the world to counter its spread. Most European countries have implemented social distancing and shelter-in-place measures. These measures are comparable to generalised quarantine and prevent the spread of the virus by restricting the movement and social interactions of people who are potentially exposed.1 As of 3 May 2020, 2.5 billion people are in lockdown.2 In France, these measures have been enforced since 17 March 2020. Several studies have reported the negative effects of quarantine on stress or depression.3–5

Peritraumatic distress (PD) is defined as the emotional and physiological distress experienced during and/or immediately after a traumatic event. It is associated with a higher risk and severity of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).6 7 The Peritraumatic Distress Inventory (PDI) was created to assess the emotional and physiological experience of individuals during a traumatic event.8 Studies have shown that PDI has a good internal consistency, stability and validity. PDI items can be grouped into factors that better reflect and predict PD and PTSD: negative emotions (items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 10) and perceived life threat and bodily arousal (items 4, 7, 9, 11, 12 and 13).9 It has also been shown that a PDI score ≥14 predicts full or partial PTSD 6 weeks postinjury.10

The main objective of this study was to assess PD in France during the COVID-19 crisis in at-risk patients. The secondary objectives were to describe the patients’ characteristics that can be used to predict the risk of PD and PTSD. In order to do so, we built an e-cohort: users of four medical chatbots designed to support patients with (1) asthma, (2) breast cancer, (3) depression and (4) migraine were invited to participate in an online survey. A chatbot is a software leveraging artificial intelligence to provide a natural language conversation with a user. They can be used to monitor patients during treatment or to collect patient-reported outcomes.11 Vik chatbots, developed by Wefight, have been shown to provide assistance with patient support and adherence to treatment.12 They are also capable of providing medical information to breast cancer patients with a level of quality comparable with that of physicians, as shown in the phase III randomised controlled trial INCASE (NCT03556813).13 The ‘Vik Asthme’ chatbot is dedicated to information and management of asthma-related symptoms, the ‘Vik Breast’ chatbot has been specialised for the management of patients with breast cancer, the ‘Vik Depression’ chatbot provides assistance to patients with symptoms of depression and the ‘Vik Migraine’ chatbot is helpful for patients with chronic migraine.

People with asthma are populations at increased risk of severe viral respiratory infections that can also induce exacerbations. The SARS-CoV-2 can induce asthma exacerbations that are a source of additional stress for asthma patients. Initial data show that patients with asthma do not appear to be over-represented in patients with COVID-19.14 15 In order to mitigate the lack of pathology control and treatment adherence during travel restrictions, the French government has implemented solutions to facilitate the renewal of treatment in the long term.16 In addition, 60 000 hospitalisations are attributable to asthma every year in France.17 This pandemic is of significant concern in patients with cancer who are at high risk of complications due to several predisposing factors.18–20 In patients with breast cancer, management must be tailored and cannot be delayed. European countries have increased the use of telehealth systems to reduce the number of hospital visits. In Italy, these changes in care led to the patients having many questions, which can generate severe stress or anxiety.21 The initial studies conducted in China following the COVID-19 pandemic have shown the impact on the mental health of healthcare workers, with an increased risk of depression and anxiety.22 Patients already diagnosed with depressive disorder could be at a high risk of distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, migraine is a pathology with a high prevalence: it is estimated to be between 17% and 21% in adults aged 18–65 years23 with a sex ratio of three women to one man.24 Despite its high prevalence, migraine remains an underdiagnosed and undertreated condition in the general population. Migraine can have a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life.25 Migraines can worsen in times of stress. This period of pandemic can generate a new source of stress and aggravate the pathology.

Patients and methods

Participants

The study was conducted in France between 31 March 2020 and 7 April 2020. The participants were users of the four different Vik chatbots. They were contacted online to participate in a survey assessing their level of stress during the COVID-19 crisis. The inclusion criteria were to be of legal age and to have breast cancer, asthma, migraine or depression. The exclusion criteria were users who were unable to formulate their non-opposition, who had insulted the chatbot, who had dialogues that made no sense or users with uncompleted questionnaires.

Intervention

A self-report questionnaire, the PDI, was used. PD is defined as the emotional and physiological distress experienced during and/or immediately after a traumatic event.8 9 It is the standard tool designed to assess psychological distress in times of crisis.26 It consists of 13 questions rated from 0 (not at all true) to 4 (extremely true). It explores the frequency of anxiety, depression, specific phobias, cognitive changes, avoidance and compulsive behaviours, physical symptoms and loss of social interaction in patients in the past one week. The total score, ranging from 0 to 52, is the sum of all items. A score greater than or equal to 14 indicates significant distress. The French validation of the PDI has a good internal cohesion, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.83.26

Data collection

The PDI questionnaire was presented to the participants by text messages. Users were asked to click on a button corresponding to the score they wished to give their status. There was no actual conversation per question, nor was there a need for natural language processing for each question. Classical demographic information (age, sex, city and professional profile), level of knowledge and use of internet tools and the presence or absence of symptoms related to COVID-19 were also assessed.

Ethical and regulatory issues

Participants were not paid. The collected data were anonymised and then hosted by Wefight on a server that meets the requirements for storing health data. Consent was collected online before the start of the study. This study was registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov database. In accordance with French and European laws on information technology and liberties (Commission Nationale Informatique et Libertés, registration n° 2217452, General Regulations for Data Protection), users had the right to access the data to verify its accuracy and, if necessary, to correct, complete and update it. They also had a right to object to the use of their data and a right to delete such data. The general conditions for the use of the data were presented and explained very clearly. They had to be accepted before accessing the questionnaire.

Statistical analysis

The description of the included populations was carried out using conventional statistical tools. For the quantitative variables we used the calculation of the mean, the standard deviation (SD), the median and the quartiles. For the qualitative variables we used numbers and percentages with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The population density was defined by French Government’s Direction of evaluation, prospection and performance.27

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to detect patients’ attributes with a significant effect on PDI, which is set as the only dependent variable. In addition, a binomial logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the patients’ features associated with a PDI ≥14, because this subpopulation is at a higher risk of partial or full PTSD 6 weeks after the traumatic event.9 A binomial variable is built splitting PDI >14 and PDI ≤14 and set as the dependent variable. For both analyses, independent variables are participant’s group (breast cancer, asthma, depression and migraine), age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64 and ≥65 years), sex (male or female), profession (employed, unemployed and other), smartphone/computer usage (<1 hour a day, 1–6 hours and >6 hours a day) a day and population density (low, medium or high).

PDI items were grouped into two factors that have been shown to better reflect and predict PD and PTSD: negative emotions (items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 10) and perceived life threat and bodily arousal (items 4, 7, 9, 11, 12 and 13). For those groups of factors, an ANOVA was performed with the same independent variables as before and the patient’s mean rate for each group of items as the dependent variable. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated between the average PDI and the number of infected people in each French region and was tested to be equal to 0.

Results

Cohort description

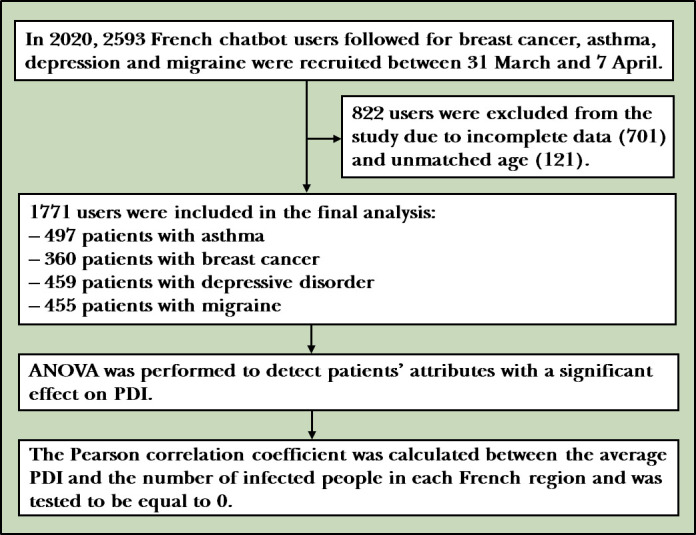

The study included 2593 participants. We excluded 822 of them because they were not eligible (incomplete questionnaires and age requirements). The total sample size was 1771 (responding rate=72.9%) (figure 1). Overall, 91.25% (n=1616) were female with a mean age of 32.8 (13.71) years, 7.96% (n=141) were male with a mean age of 28.0 (8.14) years and 0.79% (n=14) were ‘other’ with a mean age of 25.6 (8.85) years (table 1). In total, 3.3% (n=58) of participants were using a smartphone or computer less than an hour a day, 55.5% (n=983) for more than 1 hour but less than 6 hours a day and 41.22% (n=730) more than 6 hours a day. 87.86% (n=1556) had been using the internet for more than 5 years. During the survey period, 25.86% (n=458) were working as usual, 27.67% (n=490) were unemployed, 22.92% (n=406) were teleworking and 23.55% (n=417) were unemployed due to the pandemic and containment measures. Professional profiles are detailed in table 1. Regarding the population density, 7.4% (n=131) of participants were in a low (rural), 19% (n=335) in a medium (urban) and 73.7% (n=1305) in a high population density area.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study. ANOVA, analysis of variance; PDI, Peritraumatic Distress Inventory.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included participants (n=1771)

| Characteristics | % or mean (SD) |

| Gender | |

| Female (n=1616) | 91.25% |

| Male (n=141) | 7.96% |

| Other (n=14) | 0.79% |

| Age (years) | 32.4 (13.39) |

| Smartphone/computer usage time (>6 hours/day) (n=730) | 41.22% |

| Internet experience (>5 years) (n=1556) | 87.86% |

| Profession | |

| Farmer holding (n=14) | 0.80% |

| Artisan, dealer or business manager (n=55) | 3.16% |

| Manager or intellectual profession (n=112) | 6.32% |

| Intermediate profession (n=99) | 5.59% |

| Employee (n=689) | 38.74% |

| Worker (n=74) | 4.18% |

| Retired (n=52) | 2.94% |

| No professional activity (n=676) | 38.18% |

A total of 27.83% (n=493) declared they had symptoms of COVID-19, twenty-one participants tested positive, 11 negative and 461 were not tested. Of the 1771 respondents, 61.66% (n=1092) would have liked to be screened for COVID-19.

The four groups included 497 patients with asthma (from the ‘Vik Asthma’ chatbot), 360 patients with breast cancer (from the ‘Vik Breast’ chatbot), 459 patients with depressive disorder (from the ‘Vik Depression’ chatbot) and 455 from the Vik Migraine group.

Findings

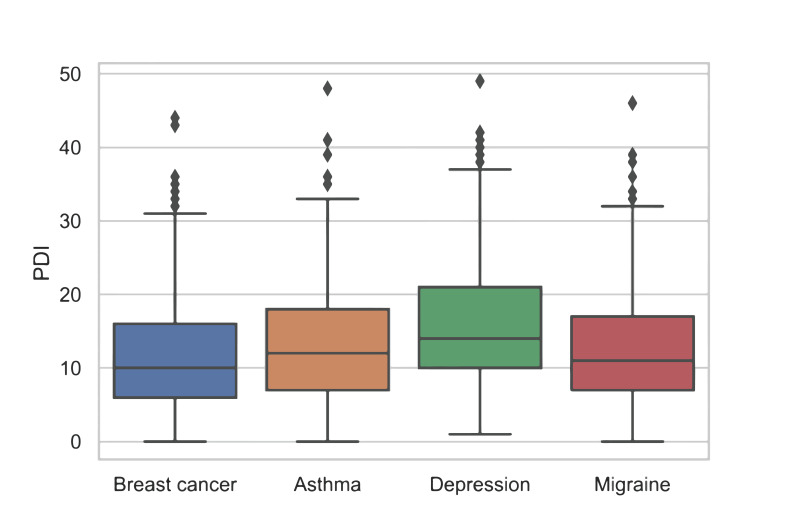

The global mean PDI score was 13.48 (8.02). Median PDI was 127–18 for patients with asthma, 106–16 for patients with breast cancer, 1410–21 for patients with depressive disorder and 117–17 for patients with migraine (figure 2). Scores for each item are shown in table 2.

Figure 2.

PDI for each group of participants. PDI, Peritraumatic Distress Inventory.

Table 2.

Mean score, SD and quartiles for each item of the PDI

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Total | |

| Mean | 1.05 | 1.52 | 1.53 | 1.51 | 0.29 | 0.79 | 2.44 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 1.23 | 0.67 | 0.1 | 0.41 | 13.48 |

| SD | 1.15 | 1.29 | 1.3 | 1.35 | 0.77 | 1.17 | 1.26 | 1.24 | 1.16 | 1.23 | 1.07 | 0.43 | 0.85 | 8.02 |

| 25% | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| 50% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| 75% | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 18 |

PDI, Peritraumatic Distress Inventory.

In total, 38.06% (674) of the respondents had psychological distress (score ≥14). Prevalence of PD was 42% for patients with asthma (209/497), 34% for patients with breast cancer (123/360), 54% for patients with depressive disorder (246/459) and 39% for patients with migraine (178/455).

The ANOVA analysis showed that sex (F=−3.217, p=0.001), unemployment (F=4.503, p<0.001) and depression (F=4.966, p<0.001) were significantly associated with a higher PDI score.

Patients using their smartphones or computers more than 1 hour a day also had a higher PDI score (F=−2.230, p=0.026).

Binomial logistic regression shows that patients with depression had a 53% (OR: 1.53, 95%CI: 1.18 to 1.99) increased risk (Z=3.207, p=0.001) of developing PD, while patients under 34 years of age had a 72% (OR: 1.72, 95% CI: 1.04 to 2.89) increased risk (Z=2.094, p=0.036), women had a 63% (OR: 1.63, 95% CI: 1.12 to 2.38) increased risk (Z=2.549, p=0.011) and unemployed patients had a 38% (OR: 0.38, 95% CI: 1.12 to 1.71) increased risk (Z=3.033, p=0.002).

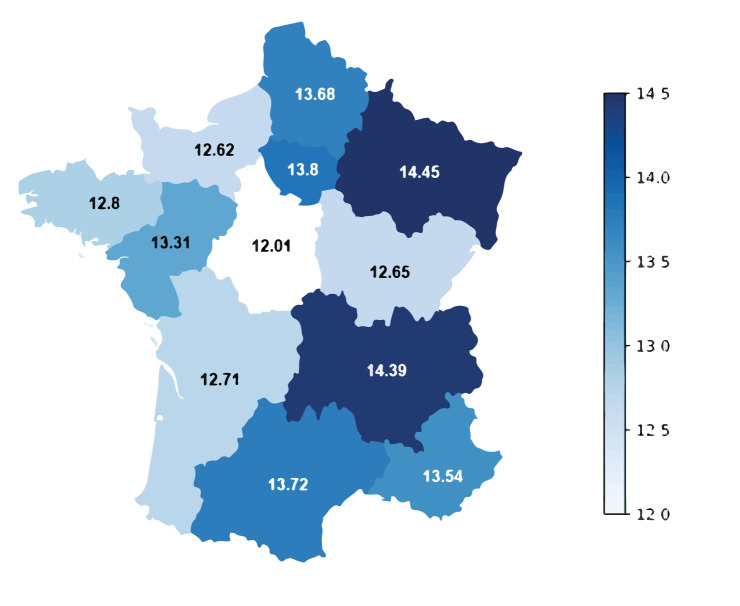

PDI was significantly higher in regions with higher COVID-19 prevalence (F=2.263, p=0.024) (Pearson correlation coefficient=0.58) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Average PDI in each of the 11 regions of France. PDI, Peritraumatic Distress Inventory.

The negative emotions factor was significantly associated with depression (F=6.705, p<0.001), age higher than 65 years (F=2.288, p=0.022), being a woman (F=2.816, p=0.004), living in a low population density area (F=2.478, p=0.013), being unemployed (F=4.845, p<0.001) and using a smartphone or computer more than 6 hours a day (F=2.105, p=0.035).

The life threat and bodily arousal factor was significantly associated with depression (F=4.689, p<0.001), being younger than 34 years of age (F=2.416, p=0.015), being a woman (F=2.942, p=0.003), living in a low population density area (F=2.755, p=0.005) and being unemployed (F=2.553, p=0.010).

Discussion

Main findings

The first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, and has since brought unprecedented efforts from governments all over the world to limit its spread. These steps have included social distancing and global shutdowns. Their precise consequences on mental health are still unknown. It is currently considered that the risk for mental health is outweighed by the need to prevent infections. The available literature on the mental health consequences of pandemics are more focused on the sequelae of the infection; however, other catastrophic events, such as the World Trade Centre terrorist attacks, were followed by an increase in depression and PTSD cases, substance abuse, domestic violence and child abuse.28 In that regard, the 2006 SARS epidemic also induced an increase in PD and PTSD in patients and clinicians.29 COVID-19 could also have the same effect, specifically because of the strong mitigation strategies that have been enforced all over the world, on a scale never seen before, and the major economic disruptions it has induced.30

The aim of our study was to quantify PD on a national scale in a country that has been hard-hit by COVID-19. We used a chatbot-administered standardised and a validated tool specifically designed to rate PD, the Psychological Distress Inventory.8 We showed that, in four groups of patients at-risk to develop PD and PTSD, the prevalence of psychological distress was 38.06% (n=674). These patients are also at high risk to develop partial of full PTSD 6 weeks after the evaluation, as shown by Bunnell et al.9 Within those four groups of patients, women, unemployed (p<0.001) and depressed (p<0.001) patients had significantly higher PDI score. Interestingly, patients using their smartphones or computers more than 1 hour a day also had a higher PDI score (p=0.026). This could also highlight the potential negative psychological impact of information and/or social networks in the context of such an event.

Limitations

There are limitations that should be considered when interpreting our results: first, a majority of participants were women (91.25%). This is due in part to the fact that one of the four groups explored consisted of patients with breast cancer, but it could also show that men are less likely to participate in this kind of online self-reported survey. This fact could potentially bias the results and specifically the value of the features we found to be associated with a PDI over 14 (predictive of PTSD). Another limitation is due to the sampling technique itself, relying on groups of patients already using the chatbots, excluding patients not using them. This study still holds interesting results because of the large cohort of respondents, the adequate geographical spread across France and the sampling time frame that corresponds to the pandemic peak in France. Another limitation is the lack of baseline measures for these cohorts: for example, we can only show that patients with depression had a higher PDI score during the COVID-19 crisis, without concluding that this is directly related to COVID-19.

Other studies have been conducted to measure the impact of COVID-19 among the general population. In Italy, Rossi et al31 conducted a web-based survey on 18 147. They found high rates of negative mental health outcomes 3 weeks into the COVID-19 lockdown: 37% of the participants declared they had symptoms of PTSD, 17.3% of depression and 20.8% of anxiety. Like in our study, the majority of respondents were women (79.6%).

Implications

Overall, policy makers are rightfully concerned by the potential negative effects of COVID-19 on public health, beyond the pandemic itself. In the UK, psychological first aid guidance has been issued by Mental Health UK.32 In France, several psychological support hotlines have been created for healthcare professionals33 and the general public.34 The precise mental health sequelae of the pandemic are still unknown but should not be neglected. In the coming weeks, months and years, we need to thoroughly investigate these consequences to be able to correctly address them. Specific efforts should be made to lower the risk of PD, depression, suicide, substance abuse and domestic violence; otherwise, the long-term consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic could be even more dire, should they remain unexplored, unaddressed and ultimately forgotten.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has a significant impact on psychological distress in patients with breast cancer, asthma, depression and migraine: 38% of participants have a PDI ≥14. This population is also at increased risk of partial or full PTSD. Specifically, women, unemployed and depressed patients are at an even higher risk. Patients using their smartphones or computers more than 1 hour a day are also at higher risk to develop PD. These measures call for systematic evaluation of the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in countries where lockdowns were enforced (2.5 billion people as of 3 May 2020).

Biography

Benjamin Chaix obtained a bachelor’s degree in Audiology in 2008 and a master’s degree in Biotechnology in 2010 from the Faculty of Pharmacy of Montpellier in France. He was a clinical engineer at the Institute of Neurosciences of Montpellier from 2010 to 2014. Since 2017, he has been working in the ENT and Head and Neck surgery department of the hospital Gui de Chauliac in Montpellier and is a lecturer at the University of Montpellier. In addition, BC is also the head of clinical operations of Wefight, a digital medicine company focused on artificial intelligence that develops chatbots to support patients with chronic diseases. He has conducted several studies or clinical trials on patients with breast cancer and depression or mood disorders. His research interests include cognition, natural language processing, and therapeutic education.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by Wefight.

Competing interests: GD, AG and BB are employees of Wefight. BC and J-EB own shares of Wefight.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. BC had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.CDC Quarantine and Isolation | Quarantine [Internet], 2019. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/index.html

- 2.Statista Infographics Infographic: What Share of the World Population Is Already on COVID-19 Lockdown? [Internet]. Available: https://www.statista.com/chart/21240/enforced-covid-19-lockdowns-by-people-affected-per-country/

- 3.Bai Y, Lin C-C, Lin C-Y, et al. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv 2004;55:1055–7. 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry 2009;54:302–11. 10.1177/070674370905400504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2013;7:105–10. 10.1017/dmp.2013.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorman KR, Engel-Rebitzer E, Ledoux AM, et al. Peritraumatic experience and traumatic stress : Martin CR, Preedy VR, Patel VB, et al., Comprehensive guide to post-traumatic stress disorders [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016: 907–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas Émilie, Saumier D, Brunet A. Peritraumatic distress and the course of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a meta-analysis. Can J Psychiatry 2012;57:122–9. 10.1177/070674371205700209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunet A, Weiss DS, Metzler TJ, et al. The Peritraumatic distress inventory: a proposed measure of PTSD criterion A2. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1480–5. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.9.1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bunnell BE, Davidson TM, Ruggiero KJ. The Peritraumatic distress inventory: factor structure and predictive validity in traumatically injured patients admitted through a level I trauma center. J Anxiety Disord 2018;55:8–13. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guardia D, Brunet A, Duhamel A, et al. Prediction of trauma-related disorders: a proposed cutoff score for the peritraumatic distress inventory. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2013;15. 10.4088/PCC.12l01406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bibault J-E, Chaix B, Nectoux P, et al. Healthcare ex machina: are conversational agents ready for prime time in oncology? Clin Transl Radiat Oncol 2019;16:55–9. 10.1016/j.ctro.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaix B, Bibault J-E, Pienkowski A, et al. When Chatbots meet patients: one-year prospective study of conversations between patients with breast cancer and a Chatbot. JMIR Cancer 2019;5:e12856. 10.2196/12856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bibault J-E, Chaix B, Guillemassé A, et al. A Chatbot versus physicians to provide information for patients with breast cancer: blind, randomized controlled Noninferiority trial. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e15787. 10.2196/15787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J-J, Dong X, Cao Y-Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 2020;75:1730–41. 10.1111/all.14238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lupia T, Scabini S, Mornese Pinna S, et al. 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak: a new challenge. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2020;21:22–7. 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.fiche-pharmacien-regles-derogatoires-delivrance-medicaments.pdf [Internet]. Available: https://www.ameli.fr/sites/default/files/Documents/670441/document/fiche-pharmacien-regles-derogatoires-delivrance-medicaments.pdf

- 17.Afrite A, Allonier C, Com-Ruelle L, et al. L’asthme en France en 2006 : prévalence et contrôle des symptômes. 8, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.El Ramahi R, Freifeld A, Epidemiology FA. Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of influenza infection in oncology patients. J Oncol Pract 2019;15:177–84. 10.1200/JOP.18.00567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:335–7. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission in patients with cancer at a tertiary care hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:1108 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Indini A, Aschele C, Cavanna L, et al. Reorganisation of medical oncology departments during the novel coronavirus disease-19 pandemic: a nationwide Italian survey. Eur J Cancer 2020;132:17–23. 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.03.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen J, Liu X, Wang D, et al. Multiple Risk Factors of Depression and Anxiety in Medical Staffs: A Cross-Sectional Study at the Outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in China [Internet]. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3551414 [Google Scholar]

- 23.ANAES [Recommendations for clinical practice. Review of diagnosis and treatment of migraine in the adult and child October 2002. Professional recommendations and references: economic evaluation service]. Rev Neurol 2003;159:S5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stovner LJ, Andree C. Prevalence of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 2010;11:289–99. 10.1007/s10194-010-0217-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jehel L, Brunet A, Paterniti S, et al. [Validation of the Peritraumatic Distress Inventory's French translation]. Can J Psychiatry 2005;50:67–71. 10.1177/070674370505000112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministère de l’Education Nationale et de la Jeunesse Une typologie des communes pour décrire le système éducatif [Internet]. Available: https://www.education.gouv.fr/une-typologie-des-communes-pour-decrire-le-systeme-educatif-6524

- 28.Neria Y, Nandi A, Galea S. Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: a systematic review. Psychol Med 2008;38:467–80. 10.1017/S0033291707001353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee AM, Wong JGWS, McAlonan GM, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry 2007;52:233–40. 10.1177/070674370705200405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020;383:510–2. 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossi R, Socci V, Talevi D, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and Lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:790. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mental Health UK Covid-19 and your mental health [Internet]. Available: https://mentalhealth-uk.org/help-and-information/covid-19-and-your-mental-health/

- 33.DGOS_Michel.C. COVID-19 [Internet]. Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé, 2020. Available: http://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/prevention-en-sante/sante-et-travail/observatoireQVT/article/covid-19

- 34.Plateforme téléphonique -Coronavirus (Covid-19): numéros utiles | service-public.fr [Internet]. Available: https://www.service-public.fr/particuliers/actualites/A13894