Abstract

Intrinsic β-cell circadian clocks are important regulators of insulin secretion and overall glucose homeostasis. Whether the circadian clock in β-cells is perturbed following exposure to prodiabetogenic stressors such as proinflammatory cytokines, and whether these perturbations are featured during the development of diabetes, remains unknown. To address this, we examined the effects of cytokine-mediated inflammation common to the pathophysiology of diabetes, on the physiological and molecular regulation of the β-cell circadian clock. Specifically, we provide evidence that the key diabetogenic cytokine IL-1β disrupts functionality of the β-cell circadian clock and impairs circadian regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. The deleterious effects of IL-1β on the circadian clock were attributed to impaired expression of key circadian transcription factor Bmal1, and its regulator, the NAD-dependent deacetylase, Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). Moreover, we also identified that Type 2 diabetes in humans is associated with reduced immunoreactivity of β-cell BMAL1 and SIRT1, suggestive of a potential causative link between islet inflammation, circadian clock disruption, and β-cell failure. These data suggest that the circadian clock in β-cells is perturbed following exposure to proinflammatory stressors and highlights the potential for therapeutic targeting of the circadian system for treatment for β-cell failure in diabetes.

Keywords: β-cell, circadian clock, inflammation, cytokines, diabetes

The circadian system is a critical component of the homeostatic process, permitting time-dependent regulation of essential physiological functions (1), including the regulation of glucose metabolism and metabolic health (2). Indeed, growing evidence from epidemiological, clinical, and animal studies link circadian disruptions with the development of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (3, 4). This relationship is mediated in part through the circadian disruption of pancreatic β-cell functionality (5), suggesting that misregulation of the circadian system may play an important role in the induction and progression of β-cell failure in diabetes (6).

Cell- and tissue-specific circadian rhythms are generated by a molecular clock comprised of transcriptional activator BMAL1 and its heterodimer CLOCK as well as repressor genes that encode period (PER1, 2, 3) and cryptochrome (CRY1, 2) proteins (7). The BMAL1:CLOCK heterodimer generates circadian rhythms through complex DNA binding with concurrent recruitment of ubiquitous and cell-specific enhancers, coactivators, and histone-modifying enzymes that are important for the activation of target genes (7). In β-cells, BMAL1-controlled genes permit the regulation of insulin secretion through the epigenetic control of transcripts involved in intracellular metabolic signaling and exocytosis (8, 9). Moreover, Bmal1 loss-of–function studies show that circadian clocks are essential for the regulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, β-cell maturation, turnover, and response to oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress (10–13). Despite an increased appreciation for the function of circadian clocks in β-cells, the impact of common diabetogenic stressors (eg, inflammation, glucotoxicity, lipotoxicity, etc) on the β-cell circadian clock remains incompletely understood.

Among common diabetogenic stressors, exposure to proinflammatory cytokines plays a prominent role in the development and progression of both Type 1 (T1DM) and T2DM diabetes mellitus (14, 15). In T1DM, β-cells are primarily exposed to interleukin (IL-) 1β, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and interferon–γ (IFNγ) due to autoimmune-mediated focal cytokine release (14). In T2DM, cytokine exposure is a result of the complex interplay between (1) adipose-derived circulating cytokines (eg, IL-1β and IL-6) (16), (2) IL-1β release through islet-associated macrophages (17), and (3) islet cell-derived cytokine production (18). Importantly, exposure of islets to proinflammatory cytokines recapitulates many aspects of β-cell dysfunction due to alterations in transcriptional networks spanning key pathways regulating metabolism, insulin biosynthesis, secretion, and turnover (19, 20).

Accumulating studies point to a complex relationship between the induction of inflammation and the regulation of the circadian clock (21–24). For example, disruption of clock function contributes to the pathogenesis of common proinflammatory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma (25), whereas activation of proinflammatory signaling (NF-κB), controls core circadian clock and clock-controlled gene expression (21). In this report, we provide evidence that among tested diabetogenic cytokines exposure to IL-1β significantly disrupts the β-cell circadian clock and circadian control of insulin secretion. This process is mediated in part through impaired expression of the only nonredundant circadian transcription factor, BMAL1, through regulation of Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) deacetylase. Moreover, we also provide evidence that the development of T2DM is associated with attenuated immunoreactivity in β-cell BMAL1 and SIRT1 expression, suggestive of a potential causative link between islet inflammation, circadian clock disruption, and β-cell failure.

Methods

Animal models

A total of 34 C57BL/6J and 35 Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP mice at age 8–12 weeks (equal proportions of male and female) were used in the current study. Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP mice were generated through breeding of Per2:LUC (26) reporter mice with mice expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the insulin promoter (27). Mice with β-cell-specific deletion of Bmal1 (β-Bmal1-/-) were generated by breeding mice homozygous for the floxed Bmal1 gene (B6.129S4 [Cg]-Arntl tm1Weit/J; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) (28) with mice transgenic for tamoxifen-inducible Cre driven by the rat Insulin2 promoter (Tg [Ins2-cre/ERT]; The Jackson Laboratory) (29). To conditionally delete Bmal1 in β-cells, (β-Bmal1-/-) mice received three i.p. injections each containing 4 mg tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) on alternate days at 2 months of age, as previously described (12). Specificity of Bmal1 deletion in pancreatic β-cells in this model has been previously validated in detail (12). All animals were housed under a standard 12 hour light, 12 hour dark (LD) cycle and provided with ad libitum chow (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN). By convention, the time of lights-on (6:00 am) is denoted as Zeitgeber Time (ZT) 0 and time of lights-off (6:00 pm ) as ZT12. A subset of mice received intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (STZ; 40 mg/kg/day in citrate buffer, pH 4.5) or vehicle on 5 consecutive days to induce β-cell failure and diabetes (30). All animal procedures were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care Committee.

Cell models

INS-1 832/13 cells were generously provided by Dr Christopher Newgard (Duke University). INS-1 832/13 cells were cultured under standard RPMI media conditions. All cytokines, IL-1β (201-LB-005/CF), IL-6 (206-IL-010/CF), TNFα (210-TA-020/CF), and IFNγ (585-IF-100/CF) were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Resveratrol was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (R5010). Bmal1 luciferase reporter INS-1 832/13 cell line (Bmal1:LUC) was generated by transducing INS-1 832/13 cells with lentiviral vectors expressing firefly luciferase under the Bmal1 promoter (vector plasmid pABpuro-BluF, a gift from Steven Brown, Addgene plasmid #46824). Lentiviral production was performed as previously described (31).

Mouse islet isolation, synchronization, and measurements of insulin secretion

Mouse islets were isolated using the collagenase method (32) and were allowed to recover overnight, incubated in standard RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. To measure circadian rhythms in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, isolated islets were synchronized through 1 hour exposure to 10 μM forskolin (8). Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion was assessed by static incubation at 4 mM glucose per 30 minutes followed by 16 mM glucose per 30 minutes, with insulin measured by ELISA (ALPCO).

Per2:LUC islet bioluminescence studies

Per2-driven bioluminescence emanating from islet cells was imaged by cooled, intensified charge-coupled device camera outfitted with a temperature- and gas-controlled incubation chamber (LV-200, Olympus, MN). Batches of 10 to 15 islets were placed in individual wells of a Nunc™ Lab-Tek™ Chambered coverglass (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), each containing standard RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.1 mM D-luciferin (Biosynth, Itaska, IL). The islets were placed in the Luminoview LV200 Bioluminescence Imaging System and bioluminescence was measured for 1 minute at intervals of 10 minutes and continuously recorded for at least 3 days. Bioluminescence signal was quantified using cellSens software (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Analysis of circadian parameters was performed using JTK_CYCLE (33).

Bmal1 luciferase assay

Bmal1:LUC transduced INS-1 832/13 cells were seeded (1 × 106 / well) and incubated with serial dilutions of IL-1β for 24 hours. Cell lysates were added to 96-well opaque plates (Costar) in duplicate and imaged on a Promega GloMax-Multi+ Detection System. Values were normalized to total protein content measured by bicinchoninic acid assay.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

INS-1 832/13 cells were plated at 1–1.5 × 106 cells/well. Following described treatments, total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Complement DNA (cDNA) was transcribed from 300 to 400 ng of RNA with the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA), and the resulting cDNA was mixed with SYBR Green Master Mix (ABI) with gene-specific primers. qRT-polymerase chain reaction analysis was performed using the ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System and the results were normalized to β-actin.

Western blot analysis

INS-1 832/13 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 106 /well. Following described treatments, total protein lysates were isolated using NP-40 buffer supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA). Protein lysates were ran on Mini-Protean TGX 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE gels (BioRad) and transferred to 0.2 µm PVDF Trans-blot Turbo membranes (BioRad) using the Trans-blot Turbo System (BioRad). Membranes were blocked in 5% milk (BioRad) and incubated with antibodies for BMAL-1 (RRID:AB_303729, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_303729) (34), CLOCK (RRID:AB_1586953, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_1586953) (35), RORα (RRID:AB_945289, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_945289) (36), Rev-Erbα (RRID:AB_2630359, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2630359) (37), SIRT1 (RRID:AB_298923, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_298923) (38), or β-actin (RRID:AB_2223041, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2223041) (39). The corresponding IRDyes (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) were used for the secondary antibodies and images were obtained with a LiCor Odyssey Fc.

Human pancreas and islet studies

Isolated human islets were obtained from Prodo Laboratories (Irvine, CA). Human pancreas was procured from the Mayo Clinic autopsy archives with approval from the Institutional Research Biosafety Board. Paraffin-embedded pancreatic sections were immunostained for Insulin (RRID:AB_306130, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_306130) (40), Bmal1 (RRID:AB_10675117, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_10675117) (41), Rorα (RRID:AB_945289, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_945289) (36), and Sirt1 (RRID:AB_2757043, https://scicrunch.org/resolver/AB_2757043) (42) with Vectashield-DAPI mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Blinded slides were viewed, imaged, and analyzed using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC, NY, USA) and ZenPro software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC.).

Statistics and calculations

Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA with post hoc tests wherever appropriate (GraphPad Prism v.6.0, San Diego, CA). Rhythmicity of in vitro glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mouse islets was assessed using Cosinor analysis with SigmaPlot 13 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL), as previously described in detail (43). All data is presented as means ± SEM and was assumed statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

In vitro exposure to IL-1β disrupts the β-cell circadian clock and circadian regulation of insulin secretion

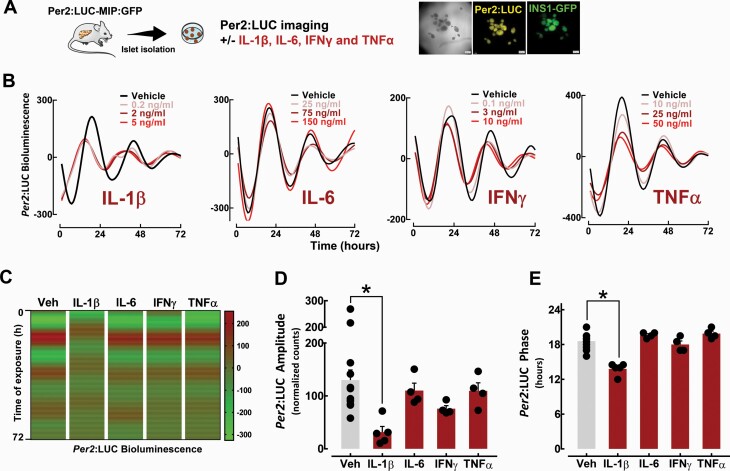

The use of clock gene luciferase fusion construct (eg, Per2) permits longitudinal assessment of peripheral circadian clocks (26). To assess the effects of proinflammatory cytokines on the β-cell circadian clock, we first used Per2:LUC (26) reporter mice crossbred with mice expressing enhanced GFP under the control of the insulin promoter (27) (Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP), which allows for examination of circadian activation of the Per2 promoter using real-time bioluminescence tracking (Fig. 1A). Isolated islets from Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP mice were treated in vitro for 72 hours to ranges of key proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, and IFNγ). These studies revealed that exposure to IL-1β (0.2–5 ng/ml) led to a significant dampening (∼80%, P < 0.05) of the amplitude and alterations in the phase (peak, 18.6 ± 0.4 vs 13.8 ± 0.5 hours for IL-1β vs vehicle, P < 0.05) of Per2-driven luciferase oscillations in β-cells (Fig. 1B–1E). Importantly, this effect was evident at concentrations previously shown to selectively reduce β-cell function (20) without a significant decrement in cell viability. Interestingly, the suppressive effect of IL-1β on the β-cell clock was in contrast to TNFα, IL-6, and IFNγ, all of which showed no significant effect on Per2-driven bioluminescence (Fig. 1B–1E).

Figure 1.

Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on β-cell circadian clock elucidated through bioluminescence recordings of islets isolated from Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP mice. A: Diagrammatic representation of the study design indicating that pancreatic islets were isolated from Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP mice to assess Per2-driven bioluminescence in response to increasing concentrations of IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, and IFNγ. B: Representative examples of circadian Per2-driven bioluminescence rhythms in batches of 10 to 15 islets isolated from Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP male and female mice exposed for 72 hours to either IL-1β (0.2–5 ng/ml), TNFα (10–50 ng/ml), IL-6 (25–150 ng/ml), or IFNγ (0.1–10 ng/ml) versus vehicle. C: Representative heat maps displaying bioluminescence traces for islets isolated from Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP mice exposed for 72 hours to either IL-1β (0.2–5 ng/ml), TNFα (10–50 ng/ml), IL-6 (25–150 ng/ml), or IFNγ (0.1–10 ng/ml) versus vehicle. D and E: Bar graphs represent mean amplitude and phase of Per2-driven bioluminescence in β-cells exposed to IL-1β (2 ng/ml), TNFα (25 ng/ml), IL-6 (75 ng/ml), IFNγ (3 ng/ml), or vehicle. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4–7 independent experiments) and *P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance versus vehicle.

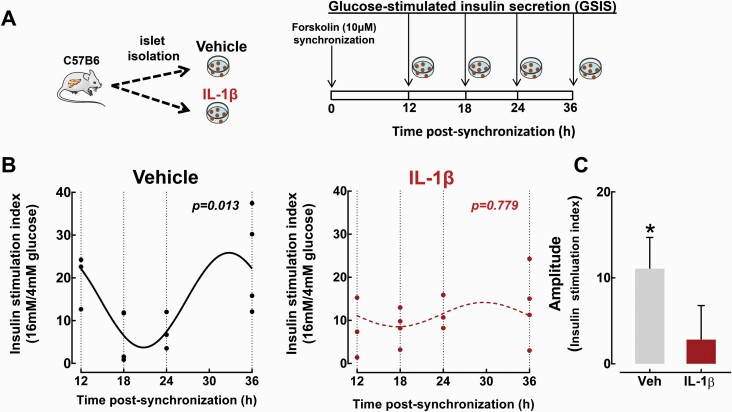

To examine whether IL-1β also disrupts circadian regulation of β-cell function, we assessed self-autonomous circadian rhythms in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in isolated mouse islets, which was recently shown to be regulated by the β-cell circadian clock (8). Consistent with previous studies (8), we observed robust time-dependent rhythms in GSIS following forskolin synchronization of control mouse islets (Cosinor regression analysis P = 0.013, Fig. 2A and 2B). Importantly, treatment with IL-1β (2 ng/ml, 24 hours) abrogated rhythmic regulation of GSIS in isolated islets, which was consistent with the inhibitory effects of IL-1β on the β-cell circadian clock (Cosinor regression analysis P = 0.779, Fig. 2A–2C).

Figure 2.

Effects of IL-1β on circadian regulation of GSIS in isolated mouse islets. A: Diagrammatic representation of the study design indicating that isolated islets from C57BL/6J mice were either treated with vehicle or IL-1β (24-hour treatment at 2 ng/ml) and subsequently synchronized with forskolin (1-hour treatment at 10 μM) to induced circadian regulation of GSIS, as previously described (8). Subsequently, GSIS was assessed at 12, 18, 24, and 36 hours postsynchronization by static incubation at basal 4 mM glucose, followed by hyperglycemia at 16 mM glucose. B: Individually plotted insulin stimulation indices (expressed as insulin release during 30 minutes at hyperglycemic 16 mM glucose over basal 4 mM glucose concentrations) at 12, 18, 24, and 36 hours postforskolin synchronization in vehicle-treated (black line) and IL-1β-treated (red line) mouse islets. Fitted black line represents significant cosine regression analysis (effect of time P < 0.05). Note the lack of statistical significance in the IL-1β-treated group. C: Average amplitude of circadian rhythm in GSIS in vehicle-treated (grey bar) and IL-1β-treated (red bar) mouse islets derived from cosine regression analysis (see “Methods” section). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM and an average of at least 3 independent experiments (from 3–4 mice per group). *P < 0.05.

In vivo exposure to diabetogenic conditions disrupts the β-cell circadian clock

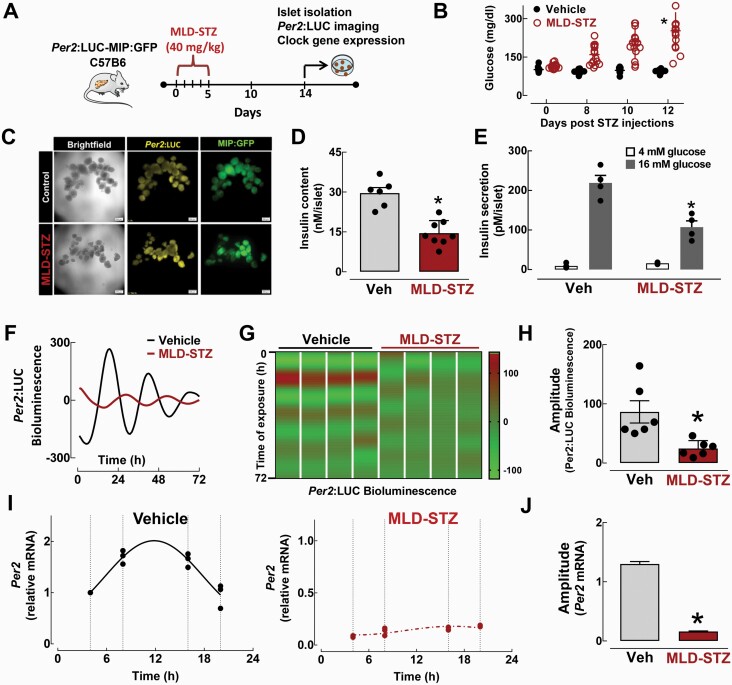

To extend our findings, we next investigated β-cell circadian clock function under proinflammatory stress in vivo. Specifically, we first assessed circadian clock function in islets isolated from Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP mice treated with multiple low dose streptozotocin (MLD-STZ), a mouse model of β-cell failure associated with inflammation, DNA damage, and oxidative stress (30, 44, 45) (Fig. 3A and 3B). Of note, all experiments involving MLD-STZ islets were performed 14 days postfinal STZ injection, at which point it was confirmed that islets displayed preserved islet integrity but attenuated (~50%) insulin content and secretory function (Fig. 3C and 3D). However, STZ-mediated induction of β-cell DNA damage and apoptosis might have also influenced islet circadian clock regulation in this study. MLD-STZ resulted in a disrupted circadian clock function characterized by significant dampening of the amplitude of Per2-driven luciferase oscillations (~70%, P < 0.05, Fig. 3F–3H). Consistently, quantitative RT-PCR performed on islets isolated at multiple time points during the LD cycle in vivo confirmed the loss of circadian rhythmicity and amplitude in Per2 mRNA expression in MLD-STZ compared to vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 3I and 3J).

Figure 3.

Effects of multiple low-dose streptozotocin (MLD-STZ)-induced β-cell failure on the β-cell circadian clock. A: Diagrammatic representation of the study design indicating that a subset of Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP and C57BL/6J mice received intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (STZ; 40 mg/kg/day) versus vehicle on 5 consecutive days to induce β-cell failure and diabetes, which was confirmed by measurements of blood glucose concentrations (B). C: Representative examples of MIP:GFP and Per2:LUC expression patterns in batches of 10 to 15 islets isolated from Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP mice exposed in vivo to MLD-STZ versus vehicle. D: Insulin content measured from islets isolated from C57BL/6J mice exposed in vivo to either MLD-STZ (red bar) versus vehicle controls (n = 6–8 independent experiments).*P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance versus vehicle. E: Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion measured during 30-minute static incubations at hyperglycemic 16 mM glucose and basal 4mM glucose concentrations in islets isolated from C57BL/6J mice exposed in vivo to either MLD-STZ versus vehicle controls (n = 4 independent experiments).*P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance versus vehicle. Representative examples of circadian Per2-driven bioluminescence rhythms (F) and corresponding heat maps (G) displaying bioluminescence traces for islets isolated from Per2:LUC-MIP:GFP mice exposed in vivo to MLD-STZ (red line) versus vehicle (black line). Each column in (G) represents an independent experiment. H: Bar graph represents mean amplitude of Per2-driven bioluminescence in β-cells exposed to MLD-STZ (red bar) or vehicle (grey bar) (n = 6 independent experiments). I: Per2 mRNA levels obtained from islet lysates of MLD-STZ (red) and vehicle (grey) mice collected at ZT 4, 8, 16, and 20 time points in the 24-hour circadian cycle. Fitted black line represents significant cosine regression analysis (effect of time P < 0.05). J: Average amplitude of circadian rhythm in Per2 mRNA in vehicle (grey bar) and MLD-STZ (red bar) islets derived from cosine regression analysis (see “Methods” section). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3–4) fold change with vehicle at ZT 4 set as 1. *P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance versus vehicle.

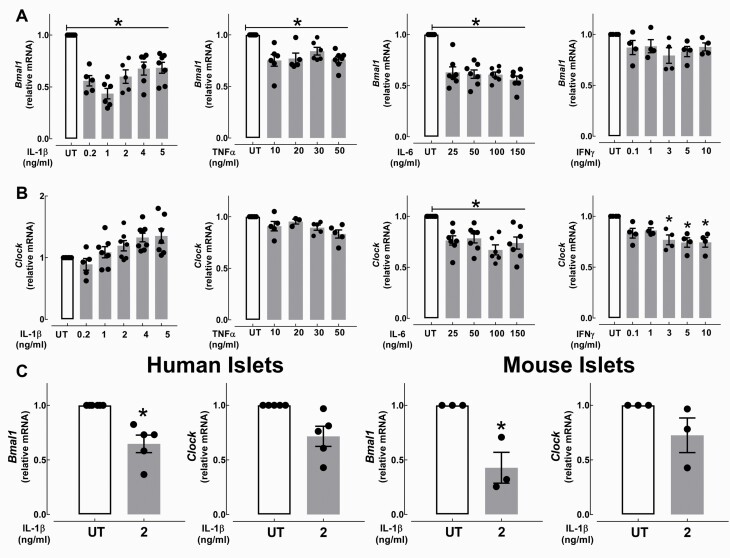

IL-1β impairs Bmal1 expression and promoter activation in β-cells

In β-cells, BMAL1:CLOCK heterodimer is required for the generation of circadian rhythms in insulin secretion through transcriptional regulation of genes regulating insulin exocytosis and various aspects of β-cell metabolism and functionality (8). Therefore, we next examined the impact of proinflammatory cytokines on the mRNA expression of Bmal1 and Clock in the INS-1 832/13 cells and isolated mouse and human islets. We found that exposure to IL-1β suppressed Bmal1 mRNA expression the most in INS-1 832/13 cells (~60%, P < 0.05, Fig. 4A), but it had no suppressive effect on Clock expression (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, other diabetogenic cytokines, namely IL-6 and TNFα, also showed modest repression of Bmal1 mRNA in INS-1 832/13 cells (P < 0.05, Fig. 4A), whereas exposure to IL-6 and IFNγ led to suppression of Clock (P < 0.05, Fig. 4B). Importantly, the suppressive effect of IL-1β on Bmal1 mRNA was reproduced in primary mouse and human isolated islets (P < 0.05, Fig. 4C), suggesting that the deleterious effects of IL-1β on the β-cell circadian clock are mediated in part through diminished Bmal1 transcription.

Figure 4.

Effects of proinflammatory cytokines on Bmal1 and Clock mRNA expression in INS-1 832/13 cells and isolated human and mouse islets. A and B: Normalized Bmal1 and Clock mRNA expression in INS-1 832/13 cells exposed for 24 hours to either IL-1β (0.2–5 ng/ml), TNFα (10–50 ng/ml), IL-6 (25–150 ng/ml), or IFNγ (0.1–10 ng/ml). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4–7 independent experiments per given concentration) and *P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance versus untreated (UT). C: Normalized Bmal1 and Clock mRNA expression in isolated nondiabetic human and mouse (C57BL/6J: 8–12 weeks old) islets exposed for 24 hours to IL-1β (2 ng/ml) versus UT. Human islet data represents n = 5 independent nondiabetic human islet shipments. Mouse islet data represents n = 3 independent experiments. Values are mean ± SEM and *P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance versus UT.

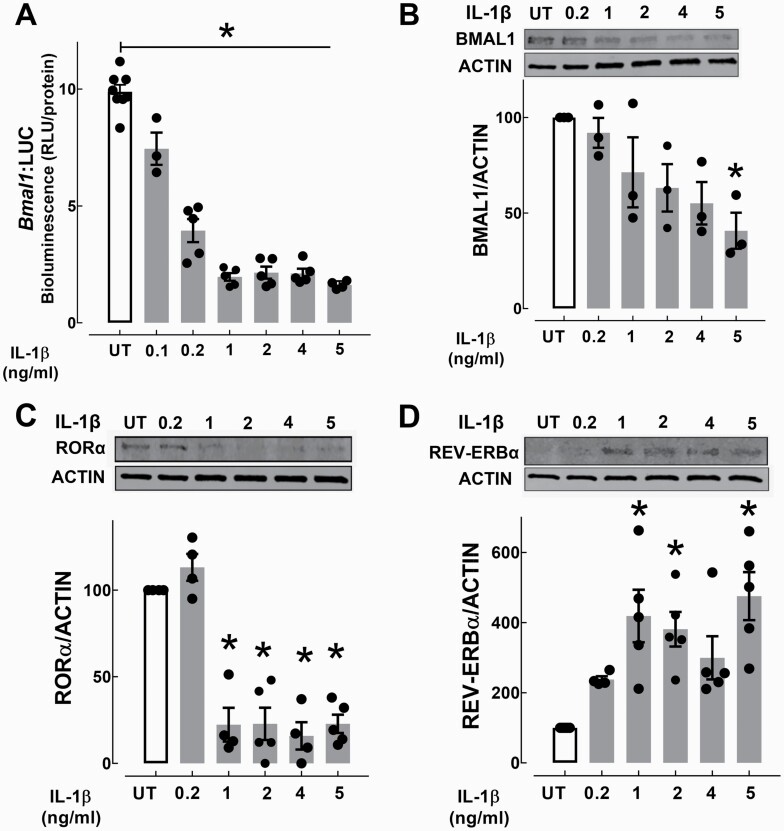

To confirm this observation, we next assessed Bmal1 promoter activity using a stably-transfected Bmal1:luciferase (Bmal1:LUC) reporter INS-1 832/13 cell line. Consistent with mRNA expression studies, IL-1β (doses from 0.1–5 ng/ml) showed dose-dependent suppression of Bmal1 promoter activation (up to 80%, Fig. 5A), which corresponded with decreased BMAL1 protein (Fig. 5B). Bmal1 expression is regulated by opposing activities of the orphan nuclear receptors RORα and REV-ERBα, which respectively play a role as activators and repressors of Bmal1 transcription through binding to RORE elements on the Bmal1 promoter (46, 47). Interestingly, exposure to IL-1β resulted in a significant decline of Bmal1 transcriptional activator RORα (~80%, Fig. 5C) and a corresponding induction of Bmal1 repressor REV-ERBα (P < 0.05, Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

Effects of IL-1β on activators and repressors of Bmal1 transcription in INS-1 832/13 cells. A: Bmal1 promoter activity was assessed using stably-transfected Bmal1:LUC reporter expressing INS-1 832/13 cells exposed for 24 hours to IL-1β (0.1–5 ng/ml). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3–6 independent experiments per given concentration) and *P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance versus untreated (UT). B–D: BMAL1, RORα, REV-ERBα protein expression assessed by Western Blotting in INS-1 832/13 β-cells exposed for 24 hours to IL-1β (0.2–5 ng/ml). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3–6 independent experiments per given concentration) and *P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance versus UT.

IL-1β impairs Bmal1 expression and β-cell function via modulation of Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) expression and activity

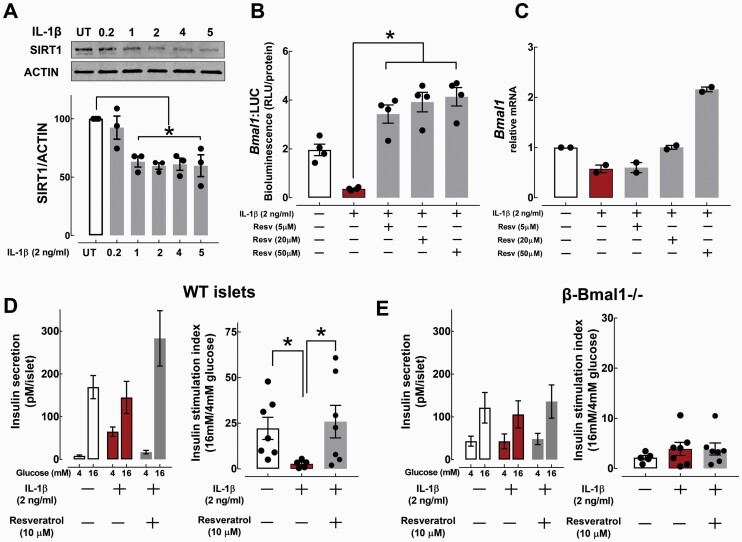

Previous studies have identified an NAD+-dependent deacetylase-Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), as a critical regulator of Bmal1 circadian gene expression, protein, and DNA binding stability, and overall circadian clock function (48–50). Moreover, SIRT1 expression and activity is disrupted in β-cells following exposure to proinflammatory cytokines in vitro (51) and in animal models of T2DM (52). Consistent with these observations, SIRT1 levels were also significantly repressed upon acute exposure to IL-1β in β-cells (P < 0.05, Fig. 6A). Importantly, treatment of INS-1 832/13 cells with a SIRT1 activator (Resveratrol) restored Bmal1 promoter activity and mRNA expression following IL-1β treatment (Fig. 6B and 6C). We next tested whether IL-1β-mediated β-cell dysfunction is also reversed upon enhancement of SIRT1 activity, and whether this occurs in a BMAL1-dependent manner. To address this, we generated mice with a conditional β-cell-specific deletion of Bmal1 (β-Bmal1-/-) and subsequently assessed GSIS in isolated islets from β-Bmal1-/- and corresponding wild-type control mice in response to IL-1β (2 ng/ml, 24 hours) or IL-1β + Resveratrol (10 μM, 24 hours) (Fig. 6D and 6E). Consistent with previous studies, IL-1β robustly suppressed GSIS in control mouse islets highlighted by ~85% reduction in the insulin stimulation index in response to 16 mM glucose (P < 0.05 vs untreated, Fig. 6D). Pretreatment with Resveratrol reversed IL-1β-mediated β-cell dysfunction by restoring GSIS in control mouse islets (P < 0.05 vs IL-1β, Fig. 6D). In contrast, islets isolated from β-Bmal1-/- mice failed to modulate GSIS upon both IL-1β and Resveratrol treatments, implying that IL-1β-mediated β-cell dysfunction is attributed at least in part to modulation of Bmal1-SIRT1 pathway (Fig. 6E). However, it is important to point out that previously reported hypothalamic expression of RIP-Cre might have influenced reported β-cell functional outcomes in β-Bmal1-/- mice.

Figure 6.

Modulation of SIRT1 activity reverses IL-1β-mediated β-cell dysfunction via BMAL1-dependent mechanism. A: SIRT1 protein expression assessed by Western Blotting in INS-1 832/13 cells exposed for 24 hours to IL-1β (0.2–5 ng/ml). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments per given concentration) and *P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance versus untreated (UT). B: Bmal1 promoter activity assessed using stable-transfected Bmal1:luciferase (Bmal1:LUC) reporter expressing INS-832/13 cells exposed for 24 hours to IL-1β (2 ng/ml) with or without cotreatment with SIRT1 chemical agonist Resveratrol (Resv) at 5, 20, and 50 μM. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4 independent experiments per given condition) and *P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance. C: Bmal1 mRNA expression assessed in INS-832/13 cells exposed for 24 hours to IL-1β (2 ng/ml) with or without cotreatment with SIRT1 chemical agonist Resv at 5, 20, and 50 μM. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 2 independent experiments per given condition). D and E: Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion assessed by static incubation at 4 and 16 mM glucose and corresponding insulin stimulation indices (expressed as insulin release during 30 minutes at hyperglycemic 16 mM glucose over basal 4 mM glucose concentrations) in WT-isolated (D) and β-Bmal1-/--isolated (E) mouse islets exposed to either vehicle, IL-1β (2 ng/ml, 24 hours), or IL-1β + Resveratrol (10μM, 24 hours). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 5–7 independent experiments per given conditions) and *P < 0.05 denotes statistical significance.

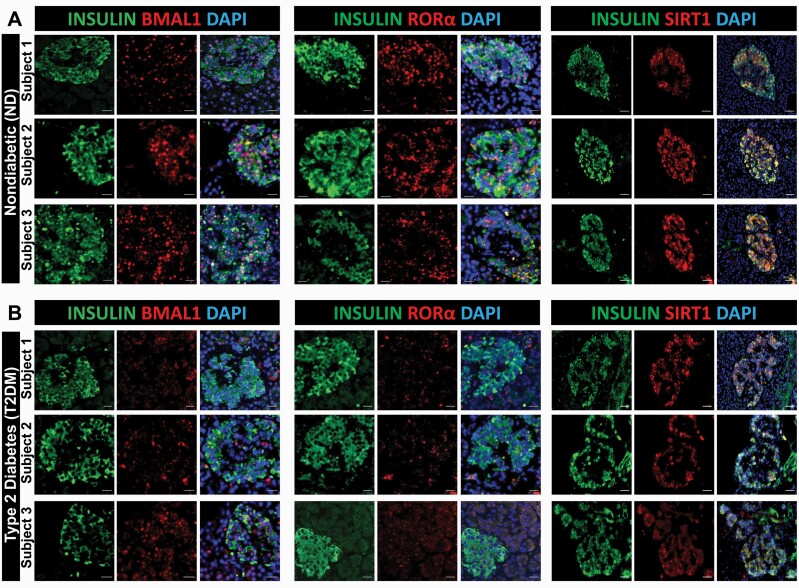

T2DM in humans is associated with reduced β-cell immunoreactivity of key circadian clock regulators BMAL1, RORα, and SIRT1

To address whether the development of diabetes in humans is associated with attenuated β-cell expression of key circadian transcriptional regulators, we performed detailed immunofluorescence analysis on autopsy-derived human pancreatic tissue collected from subjects with T2DM and age-matched nondiabetic controls (Fig. 7 and Table 1). As expected, mean fasting blood glucose (188 ± 25 vs 93 ± 5 mg/dl, P < 0.05) and body mass index (BMI) (36 ± 2 vs 25 ± 1, P < 0.05) were significantly higher in the T2DM group compared to nondiabetic controls. Consistent with our previous observations, nuclear immunoreactivity of BMAL1 was attenuated in β-cells of patients with T2DM compared to controls (Fig. 7A and 7B). Importantly, we also observed similar patterns of attenuated immunoreactivity of key Bmal1 regulators RORα and SIRT1 in β-cells of patients with T2DM (Fig. 7A and 7B).

Figure 7.

BMAL1, RORα, and SIRT1 immunoreactivity is attenuated in human T2DM β-cells. Representative examples of pancreatic islets stained by immunofluorescence for BMAL1, RORα, and SIRT1 (red), insulin (green), and counterstained with nuclear marker DAPI (blue) imaged at × 20 (BMAL1 and RORα scale bars, 20 µm; SIRT1 scale bars, 50 µm) in human pancreatic tissue obtained from Mayo Clinic autopsy archives. Graph shows 3 representative examples of nondiabetic (ND; A) and T2DM (B) subjects. In total, pancreatic specimens from n = 8 (ND) and n = 7 T2DM subjects were obtained and examined.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of subjects in the human autopsy pancreas cohort.

| Clinical Characteristics of Nondiabetic Subjects | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Age (y) | 84 | 65 | 86 | 60 | 81 | 61 | 80 | 64 |

| Sex (M/F) | M | M | M | M | M | M | F | F |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 24.0 | 21.0 | 24.7 | 27.7 | 26.1 | 22.3 | 29.8 | 20.7 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 89 | 95 | 77 | 88 | 117 | 90 | 97 | 106 |

| Time of death | 20:40 | 20:45 | 7:00 | 7:45 | 23:55 | 1:50 | 5:44 | 23:38 |

| Cause of death | Urothelial carcinoma | Acute myeloid leukemia | Sepsis | Ischemic heart disease | Acute bronchopneumonia | Biliary cirrhosis | Exsanguination | Fibrinous pneumonia |

| Clinical Characteristics of Type 2 Diabetic Subjects | ||||||||

| Case ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Age (y) | 62 | 75 | 90 | 84 | 64 | 67 | 80 | |

| Sex (M/F) | M | F | M | M | M | M | M | |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 37.6 | 32.8 | 32.0 | 33.2 | 49.7 | 32.6 | 31.0 | |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 145 | 182 | 199 | 127 | 188 | 147 | 325 | |

| Time of death | 20:24 | 22:01 | 21:50 | 3:05 | 6:15 | 22:46 | 3:30 | |

| Diabetes medication | Metformin | Glyburide, metformin | Untreated | Insulin | Insulin | Insulin | Oral agents | |

| Cause of death | Pulmonary thromboembolism | Metastatic adenocarcinoma | Acute bronchopneumonia | Multisystem organ failure | Diabetic ketoacidosis | Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | Atherosclerotic disease | |

Discussion

The development of both T1DM and T2DM is preceded by β-cell dysfunction characterized by impaired glucose-stimulated insulin secretion progressing toward β-cell apoptosis and/or dedifferentiation (53–55). Although there are many notable differences in the epidemiology and pathophysiology of β-cell failure between the 2 forms of diabetes, exposure to proinflammatory cytokines and consequent islet inflammation appears to play a prominent role in both conditions (56). However, despite an increased understanding into the biological effects of β-cell cytokine exposure and action, the molecular and physiological basis underlying the effects of proinflammatory cytokines remain incompletely understood.

The focus of the current study was on the effects of key diabetogenic cytokines on the regulation of the β-cell circadian clock and circadian control of insulin secretion. Among the individually tested cytokines, IL-1β was shown to have the most profound disruptive effect on clock-mediated circadian transcriptional and physiological oscillations in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. It is important to note that this study did not assess the combined effects of the key proinflammatory cytokines (eg, IL-1β + TNFα + IFNγ), as are commonly used to recapitulate islet cell milieu in T1DM. Moreover, previous studies also demonstrated that acute exposure to IL-1β exerts beneficial effects on β-cell function through amplification of insulin exocytosis, which contributes to islet compensation to metabolic stress (57). Factors regulating the beneficial versus deleterious effects of IL-1β on islets are complex and remain to be fully elucidated, but they likely involve differences in local cytokine exposure levels and timing, as well as the use of different experimental models.

Ample evidence describes the involvement of IL-1β in T1DM and, more recently, T2DM (14, 15, 19, 56). In T1DM, IL-1β is produced primarily by monocytes and macrophages and exerts a direct effect on β-cell function and survival, often in concert with other cytokines and chemokines (14). In T2DM, the origin of IL-1β exposure to the β-cells is more complex and controversial; however, it is likely to include a combination of systemic adipose-derived and “local” islet inflammasome/macrophage–derived IL-1β secretions (17, 58, 59). Importantly, IL-1β exposure at concentrations (and durations) used in our study has been shown to preferentially induce defects in β-cell secretory function by altering key mediators of insulin exocytosis and granular machinery (eg, Snap25) (20). Indeed, self-autonomous circadian rhythms in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion have been shown to be driven by circadian clock-mediated regulation of transcriptional enhancers encoding genes involved in the assembly and translocation of insulin-secretory granules (8). Moreover, isolated islets from T2DM patients are characterized by the impaired circadian clock corresponding to reduced insulin exocytosis and secretion (6). Moreover, exposure to proinflammatory cytokines (including IL-1β) induces activation of proapoptotic cellular programs, which has been also associated with the resetting of the circadian clock (60).

Our study shows that IL-1β disrupts the β-cell circadian clock in part through compromising the expression of a key circadian transcription factor Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like (BMAL1). Indeed, Bmal1 is the only nonredundant clock gene indispensable for the regulation of circadian rhythms in mammals (61). In β-cells, Bmal1 expression is required for the regulation of postnatal maturation (13), glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (8), β-cell turnover (12), mitochondrial function (11), and oxidative/endoplasmic reticulum stress response (62). Therefore, impaired β-cell Bmal1 expression recapitulates many features of β-cell failure in diabetes (12), including disruption in the regulation of glucose homeostasis in vivo in mice (8, 11), and in humans is associated with development of metabolic syndrome and T2DM (63). Therefore, it is plausible to hypothesize that the deleterious effects of IL-1β on the β cell are mediated at least in part through repression of Bmal1 expression and consequently compromised circadian-regulation of β-cell functions critical for the control of insulin secretion.

IL-1β appears to regulate β-cell Bmal1 expression by promoting inhibition of an NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 expression. This data is consistent with accumulating work that has identified SIRT1 as a key regulator of core circadian clock function (48–50, 64). Studies show that SIRT1 positively regulates the circadian clock through (1) enhancing Bmal1 transcription by cooperative binding with RORα and PPARγ co-activator 1α (PGC1α) (64), (2) enhancing gene transcription through deacetylation of core clock genes (eg, Bmal1 and Per2) (48), and (3) CLOCK-mediated chromatin remodeling (49). In accordance with these findings, cytokine-mediated lung epithilium inflammation (due to cigarette smoke and COPD) is associated with impaired circadian clock function due to compromised expression of the BMAL1–SIRT1 pathway (25, 65). Consistently, we also observed attenuated immunoreactivity of BMAL1 and SIRT1 in β-cells of patients with T2DM assessed in autopsy-derived pancreatic tissue. These observations implicate the loss of BMAL1–SIRT1 expression as a potential common mechanism in inflammation-mediated chronic diseases such as diabetes and COPD. Notably, in a nonhuman primate model of diet-induced diabetes, treatment with SIRT1 agonist Resveratrol was shown to reverse β-cell dysfunction and dedifferentiation (52). Future studies are warranted to address the effects of SIRT1 agonism on the regulation of islet circadian clock function under proinflammatory conditions in diabetes.

Accumulating evidence points to the importance of islet-specific circadian clocks in the regulation of insulin secretion in humans in health and during the evolution of T2DM (6, 66–69). Robust circadian rhythms in insulin secretion and glucose tolerance have been demonstrated in humans in vivo (69) and in isolated human islets in vitro (6). Correspondingly, compromised circadian regulation of insulin secretion is a characteristic feature of T2DM development in humans and was recently shown to be attributed to impaired islet circadian clock function (6, 68). Consistent with these observations, we demonstrated a pattern of decreased β-cell immunoreactivity of key circadian clock regulators BMAL1, SIRT1, and RORα utilizing human autopsy pancreatic tissue from patients with T2DM. Observation of diminished BMAL1 immunoreactivity is particularly notable given the critical role of this transcription factor in the regulation of diverse β-cell functions (70). Notably, BMAL1 belongs to the Per–Arnt–Sim (PAS) domain family of proteins, which exhibit a common function as cellular stress and homeostasis sensors (71) and subsequently are important regulators of β-cell functionality (72). Interestingly, mRNA expression of key PAS domain proteins (eg, Hif1α, Arnt, PASK, and Bmal1) have been previously shown to be suppressed in T2DM human islets and under proinflammatory conditions (72, 73). Nevertheless, lack of time-dependent islet or β-cell circadian clock protein data is a limitation of our study and many studies examining circadian clock expression in human tissues. Additional acquisition of autopsy human pancreas across the 24-hour circadian cycles and/or implementation of CYCLOPS machine learning methodology, which identifies diurnal changes in high-throughput human data sets (74), will be important for future studies to confirm changes in circadian protein/mRNA expression in vivo in human islet cells.

In conclusion, our study provides evidence that the circadian clock and subsequent circadian regulation of insulin secretion in β-cells is perturbed following exposure to a common proinflammatory cytokine Interleukin 1β, which is involved in the pathophysiology diabetes mellitus. These data add to the growing body of evidence suggesting that disruption of the islet circadian clock contributes to the induction of β-cell failure and highlights the potential for therapeutic targeting of circadian system in the treatment of diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: We acknowledge funding support from the National Institutes of Health (2R01DK098468 to A.V.M. and T32-HL105355 to N.J.).

Author Contributions: N.J. contributed to study design, conducted experiments, assisted with the data analysis, interpretation, and preparation of the manuscript. M.B. conducted experiments, assisted with the data analysis, interpretation, and preparation of the manuscript. K.R. contributed to study design, conducted experiments, and reviewed the manuscript. T.H. conducted experiments and reviewed the manuscript. S.K.S. assisted with the data analysis and reviewed the manuscript. A.V.M. designed, interpreted the studies, and wrote the manuscript. A.V.M is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of data analysis.

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

The data and datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Pittendrigh CS. Temporal organization: reflections of a Darwinian clock-watcher. Annu Rev Physiol. 1993;55:16–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bass J, Lazar MA. Circadian time signatures of fitness and disease. Science. 2016;354(6315):994–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Qian J, Scheer FAJL. Circadian system and glucose metabolism: implications for physiology and disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2016;27(5):282–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Javeed N, Matveyenko AV. Circadian etiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Physiology. 2018;33(2):138–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perelis M, Ramsey KM, Marcheva B, Bass J. Circadian transcription from beta cell function to diabetes pathophysiology. J Biol Rhythms. 2016;31(4):323–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petrenko V, Gandasi NR, Sage D, Tengholm A, Barg S, Dibner C. In pancreatic islets from type 2 diabetes patients, the dampened circadian oscillators lead to reduced insulin and glucagon exocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(5): 2484–2495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Takahashi JS. Transcriptional architecture of the mammalian circadian clock. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18(3):164–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perelis M, Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, et al. Pancreatic β cell enhancers regulate rhythmic transcription of genes controlling insulin secretion. Science. 2015;350(6261):aac4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petrenko V, Saini C, Giovannoni L, et al. Pancreatic α- and β-cellular clocks have distinct molecular properties and impact on islet hormone secretion and gene expression. Genes Dev. 2017;31(4):383–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marcheva B, Ramsey KM, Buhr ED, et al. Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes. Nature. 2010;466(7306):627–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee J, Moulik M, Fang Z, et al. Bmal1 and β-cell clock are required for adaptation to circadian disruption, and their loss of function leads to oxidative stress-induced β-cell failure in mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(11):2327–2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rakshit K, Hsu TW, Matveyenko AV. Bmal1 is required for beta cell compensatory expansion, survival and metabolic adaptation to diet-induced obesity in mice. Diabetologia. 2016;59(4):734–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rakshit K, Qian J, Gaonkar KS, Dhawan S, Colwell CS, Matveyenko AV. Postnatal ontogenesis of the islet circadian clock plays a contributory role in β-cell maturation process. Diabetes. 2018;67(5):911–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eizirik DL, Colli ML, Ortis F. The role of inflammation in insulitis and beta-cell loss in type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(4):219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Donath MY, Böni-Schnetzler M, Ellingsgaard H, Ehses JA. Islet inflammation impairs the pancreatic beta-cell in type 2 diabetes. Physiology. 2009;24(6):325–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spranger J, Kroke A, Möhlig M, et al. Inflammatory cytokines and the risk to develop type 2 diabetes: results of the prospective population-based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Potsdam Study. Diabetes. 2003;52(3):812–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Westwell-Roper CY, Ehses JA, Verchere CB. Resident macrophages mediate islet amyloid polypeptide-induced islet IL-1β production and β-cell dysfunction. Diabetes. 2014;63(5):1698–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Igoillo-Esteve M, Marselli L, Cunha DA, et al. Palmitate induces a pro-inflammatory response in human pancreatic islets that mimics CCL2 expression by beta cells in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2010;53(7):1395–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eizirik DL, Kutlu B, Rasschaert J, Darville M, Cardozo AK. Use of microarray analysis to unveil transcription factor and gene networks contributing to Beta cell dysfunction and apoptosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1005(1):55–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ohara-Imaizumi M, Cardozo AK, Kikuta T, Eizirik DL, Nagamatsu S. The cytokine interleukin-1beta reduces the docking and fusion of insulin granules in pancreatic beta-cells, preferentially decreasing the first phase of exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(40):41271–41274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hong HK, Maury E, Ramsey KM, et al. Requirement for NF-κB in maintenance of molecular and behavioral circadian rhythms in mice. Genes Dev. 2018;32(21-22):1367–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Haspel JA, Chettimada S, Shaik RS, et al. Circadian rhythm reprogramming during lung inflammation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Curtis AM, Fagundes CT, Yang G, et al. Circadian control of innate immunity in macrophages by miR-155 targeting Bmal1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(23):7231–7236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spengler ML, Kuropatwinski KK, Comas M, et al. Core circadian protein CLOCK is a positive regulator of NF-kappaB-mediated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(37):E2457–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hwang JW, Sundar IK, Yao H, Sellix MT, Rahman I. Circadian clock function is disrupted by environmental tobacco/cigarette smoke, leading to lung inflammation and injury via a SIRT1-BMAL1 pathway. Faseb J. 2014;28(1):176–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yoo SH, Yamazaki S, Lowrey PL, et al. PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(15):5339–5346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hara M, Wang X, Kawamura T, et al. Transgenic mice with green fluorescent protein-labeled pancreatic beta -cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284(1):E177–E183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Storch KF, Paz C, Signorovitch J, et al. Intrinsic circadian clock of the mammalian retina: importance for retinal processing of visual information. Cell. 2007;130(4):730–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, Melton DA. Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature. 2004;429(6987):41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sandberg JO, Andersson A, Eizirik DL, Sandler S. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents low dose streptozotocin induced diabetes in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;202(1):543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tonne JM, Campbell JM, Cataliotti A, et al. Secretion of glycosylated pro-B-type natriuretic peptide from normal cardiomyocytes. Clin Chem. 2011;57(6):864–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rakshit K, Qian J, Ernst J, Matveyenko A. Circadian variation of the pancreatic islet transcriptome. Physiol Genomics. 2016;48(9):677–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hughes ME, Hogenesch JB, Kornacker K. JTK_CYCLE: an efficient nonparametric algorithm for detecting rhythmic components in genome-scale data sets. J Biol Rhythms. 2010;25(5):372–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. RRID:AB_303729.

- 35. RRID:AB_1586953.

- 36. RRID:AB_945289.

- 37. RRID:AB_2630359.

- 38. RRID:AB_298923.

- 39. RRID:AB_2223041.

- 40. RRID:AB_306130.

- 41. RRID:AB_10675117.

- 42. RRID:AB_2757043.

- 43. de Goede P, Sen S, Su Y, et al. An ultradian feeding schedule in rats affects metabolic gene expression in liver, brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle with only mild effects on circadian clocks. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang H, Wright JR Jr. Human beta cells are exceedingly resistant to streptozotocin in vivo. Endocrinology. 2002;143(7):2491–2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kwon NS, Lee SH, Choi CS, Kho T, Lee HS. Nitric oxide generation from streptozotocin. Faseb J. 1994;8(8):529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Preitner N, Damiola F, Lopez-Molina L, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha controls circadian transcription within the positive limb of the mammalian circadian oscillator. Cell. 2002;110(2):251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sato TK, Panda S, Miraglia LJ, et al. A functional genomics strategy reveals Rora as a component of the mammalian circadian clock. Neuron. 2004;43(4):527–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Asher G, Gatfield D, Stratmann M, et al. SIRT1 regulates circadian clock gene expression through PER2 deacetylation. Cell. 2008;134(2):317–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nakahata Y, Kaluzova M, Grimaldi B, et al. The NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT1 modulates CLOCK-mediated chromatin remodeling and circadian control. Cell. 2008;134(2): 329–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Foteinou PT, Venkataraman A, Francey LJ, Anafi RC, Hogenesch JB, Doyle FJ 3rd. Computational and experimental insights into the circadian effects of SIRT1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(45):11643–11648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lee JH, Song MY, Song EK, et al. Overexpression of SIRT1 protects pancreatic beta-cells against cytokine toxicity by suppressing the nuclear factor-kappaB signaling pathway. Diabetes. 2009;58(2):344–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fiori JL, Shin YK, Kim W, et al. Resveratrol prevents β-cell dedifferentiation in nonhuman primates given a high-fat/high-sugar diet. Diabetes. 2013;62(10):3500–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52(1):102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Meier JJ, Bhushan A, Butler AE, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Sustained beta cell apoptosis in patients with long-standing type 1 diabetes: indirect evidence for islet regeneration? Diabetologia. 2005;48(11):2221–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Talchai C, Xuan S, Lin HV, Sussel L, Accili D. Pancreatic β cell dedifferentiation as a mechanism of diabetic β cell failure. Cell. 2012;150(6):1223–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Nunemaker CS. Considerations for defining cytokine dose, duration, and milieu that are appropriate for modeling chronic low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res. 2016;2016:2846570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hajmrle C, Smith N, Spigelman AF, et al. Interleukin-1 signaling contributes to acute islet compensation. JCI Insight. 2016;1(4):e86055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Masters SL, Dunne A, Subramanian SL, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by islet amyloid polypeptide provides a mechanism for enhanced IL-1β in type 2 diabetes. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hui Q, Asadi A, Park YJ, et al. Amyloid formation disrupts the balance between interleukin-1β and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in human islets. Mol Metab. 2017;6(8):833–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Tamaru T, Hattori M, Ninomiya Y, et al. ROS stress resets circadian clocks to coordinate pro-survival signals. Plos One. 2013;8(12):e82006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bunger MK, Wilsbacher LD, Moran SM, et al. Mop3 is an essential component of the master circadian pacemaker in mammals. Cell. 2000;103(7):1009–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lee J, Liu R, de Jesus D, et al. Circadian control of β-cell function and stress responses. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(Suppl 1):123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Woon PY, Kaisaki PJ, Bragança J, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like (BMAL1) is associated with susceptibility to hypertension and type 2 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(36):14412–14417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Chang HC, Guarente L. SIRT1 mediates central circadian control in the SCN by a mechanism that decays with aging. Cell. 2013;153(7):1448–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yao H, Sundar IK, Huang Y, et al. Disruption of Sirtuin 1-mediated control of circadian molecular clock and inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2015;53(6):782–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saini C, Petrenko V, Pulimeno P, et al. A functional circadian clock is required for proper insulin secretion by human pancreatic islet cells. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(4):355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pulimeno P, Mannic T, Sage D, et al. Autonomous and self-sustained circadian oscillators displayed in human islet cells. Diabetologia. 2013;56(3):497–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Boden G, Chen X, Polansky M. Disruption of circadian insulin secretion is associated with reduced glucose uptake in first-degree relatives of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1999;48(11):2182–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Boden G, Ruiz J, Urbain JL, Chen X. Evidence for a circadian rhythm of insulin secretion. Am J Physiol. 1996;271(2 Pt 1):E246–E252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Rakshit K, Thomas AP, Matveyenko AV. Does disruption of circadian rhythms contribute to beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes? Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(4):474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pellequer JL, Wager-Smith KA, Kay SA, Getzoff ED. Photoactive yellow protein: a structural prototype for the three-dimensional fold of the PAS domain superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(11):5884–5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sabatini PV, Lynn FC. All-encomPASsing regulation of β-cells: PAS domain proteins in β-cell dysfunction and diabetes. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(1):49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gunton JE, Kulkarni RN, Yim S, et al. Loss of ARNT/HIF1beta mediates altered gene expression and pancreatic-islet dysfunction in human type 2 diabetes. Cell. 2005;122(3):337–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Anafi RC, Francey LJ, Hogenesch JB, Kim J. CYCLOPS reveals human transcriptional rhythms in health and disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(20):5312–5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.