Abstract

Aims

To compare the safety and efficacy of insulin glargine 300 U/mL (Gla‐300) versus first‐generation standard‐of‐care basal insulin analogues (SOC‐BI; insulin glargine 100 U/mL or insulin detemir) at 6 months.

Methods

In the 12‐month, open‐label, multicentre, randomized, pragmatic ACHIEVE Control trial, insulin‐naïve adults with type 2 diabetes (T2D) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) 64 to 97 mmol/mol (8.0%–11.0%) after ≥1 year of treatment with ≥2 diabetes medications were randomized to Gla‐300 or SOC‐BI. The composite primary endpoint, evaluated at 6 months, was the proportion of participants achieving individualized HbA1c targets per Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) criteria without documented symptomatic (blood glucose ≤3.9 mmol/L [≤70 mg/dL]) or severe hypoglycaemia at any time of the day at 6 months.

Results

Of 1651 and 1653 participants randomized to Gla‐300 and SOC‐BI, respectively, 31.3% and 27.9% achieved the composite primary endpoint at 6 months (odds ratio [OR] 1.19, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.01–1.39; P = 0.03 for superiority); 78.4% and 75.3% had no documented symptomatic or severe hypoglycaemia (OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.01–1.41). Changes from baseline to month 6 in HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose, weight, and BI analogue dose were similar between groups.

Conclusions

Among insulin‐naïve adults with poorly controlled T2D, Gla‐300 was associated with a statistically significantly higher proportion of participants achieving individualized HEDIS HbA1c targets without documented symptomatic or severe hypoglycaemia (vs SOC‐BI) in a real‐life population managed in a usual‐care setting. The ACHIEVE Control study results add value to treatment decisions and options for patients, healthcare providers, payers and decision makers.

Keywords: basal insulin, glycaemic control, hypoglycaemia, insulin analogues, randomized trial, type 2 diabetes

1. INTRODUCTION

Basal insulin (BI) analogue options include first‐generation (eg, insulin glargine 100 U/mL [Gla‐100] and insulin detemir [IDet]) and second‐generation (eg, insulin glargine 300 U/mL [Gla‐300] and insulin degludec) preparations. Within the tightly regulated protocol‐defined settings of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), second‐generation BI analogues demonstrated similar efficacy to first‐generation BI analogues, with a comparable or reduced risk of hypoglycaemia, 1 , 2 , 3 probably attributable to improved pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, 4 , 5 , 6 and lower 24‐hour variability in blood glucose excursions. 7 , 8

Randomized controlled trials are the “gold standard” for evaluating the biological effects of new treatments 9 achieved by implementing narrow eligibility criteria, providing constant oversight, following highly regulated protocol‐defined study procedures, and ensuring maximal adherence to treatment plans and medication. However, RCT populations are often homogeneous and not fully representative of patients seen in real‐world practice, and protocol‐specified procedures do not always reflect usual clinical practice. 10 Real‐world observational studies have broader eligibility criteria; 11 with oversight and treatment approaches that reflect actual practice, they can complement RCT data and may provide a more realistic estimation of real‐world effectiveness and safety of interventions. These data can be of great value to patients, healthcare providers (HCPs), and payers. 12 Pragmatic randomized real‐life clinical studies are designed to mimic the use of interventions in a real‐world setting while maintaining the internal validity and rigour of randomization. 13 , 14 They can bridge the gap between efficacy outcomes of highly regulated RCTs and real‐life treatment effectiveness of real‐world clinical practice.

ACHIEVE Control is the first randomized prospective pragmatic real‐life study to investigate the efficacy and safety of Gla‐300 versus first‐generation standard‐of‐care BI analogues (SOC‐BI; Gla‐100 or IDet) in insulin‐naïve adults with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes (T2D) on their current anti‐hyperglycaemic medication. ACHIEVE Control used a composite primary endpoint to determine whether Gla‐300, versus SOC‐BI, increased the likelihood that insulin‐naïve adults with T2D and elevated glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) attain individualized HbA1c targets without experiencing hypoglycaemia after 6 months. The study design imposed minimal restrictions on participant eligibility and study conduct to assess Gla‐300 efficacy and safety under usual‐care conditions.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

The design of ACHIEVE Control (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02451137) has been reported previously. 15 ACHIEVE Control was a large, 12‐month, randomized, prospective, open‐label, active‐controlled, two‐arm, multicentre, parallel‐group, pragmatic trial conducted in the United States and Canada.

Enrolment occurred from June 2015 to July 2017. Eligible participants were insulin‐naïve adults (≥18 years) with American Diabetes Association (ADA)‐defined T2D 16 diagnosed ≥1 year before the screening visit and with inadequate glycaemic control (HbA1c ≥64 mmol/mol [8.0%]) after ≥1 year of treatment with ≥2 diabetes medications (oral antihyperglycaemic drugs [metformin, sulphonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors, or sodium‐glucose co‐transporter type 2 inhibitors] or glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists [GLP‐1RAs]) approved for daily concomitant use with insulin (Victoza®, Byetta®, Adlyxin®). Exclusion criteria were an HbA1c >97 mmol/mol (11.0%), type 1 diabetes, contraindications to insulin, or any major systemic disease resulting in short life expectancy that, in the opinion of the investigator, would restrict or limit successful participation for the study duration. Pregnant or breastfeeding women and women with childbearing potential and no effective contraception were excluded.

The trial protocol was approved, in accordance with local regulations at the study sites, by the appropriate institutional review boards/independent ethics committees, and the trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all its amendments, the International Conference on Harmonization guidelines for good clinical practice, and all applicable laws, rules and regulations. All participants provided informed consent. Various protocol amendments were implemented after study initiation (Table S1).

Payer, research organization (including HealthCore and Comprehensive Health Insights, research subsidiaries of Anthem, Inc. and Humana, respectively), and HCP databases were analysed to identify potential clinical sites, and databases from the selected sites were used to identify potential study participants. Clinicians at the selected sites, many of whom were primary care physicians with no or limited prior clinical trial experience, screened participants for study inclusion.

2.2. Randomization and treatment

Participants were randomized (1:1) to Gla‐300 or SOC‐BI and stratified by individualized HbA1c treatment target (<53 mmol/mol [7.0%]/<64 mmol/mol [8.0%]), sulphonylurea use (yes/no), GLP‐1RA use (yes/no), and baseline HbA1c (</≥75 mmol/mol [9.0%]). For participants randomized to the SOC‐BI arm, investigators had the choice of using either Gla‐100 or IDet, based on their usual practice and clinical preference. Randomization was performed via an interactive voice response system by Perceptive Informatics (now PAREXEL Informatics, East Windsor, NJ, USA), which provided on‐demand treatment allocation. Statisticians, data managers, and the study sponsor were blinded to treatment arm allocation.

Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) criteria 15 , 17 were used to assign individualized HbA1c targets in order to reflect more realistic expectations for glycaemic control in real‐world practice, as well as common payer metrics and expectations in the United States. An eligibility cut‐off of HbA1c ≥64 mmol/mol (8.0%) was chosen to represent the threshold at which physicians might be more likely to consider initiating insulin therapy.

Participants received prescriptions for their assigned BI analogue along with instructions from their clinician to titrate the dose to a target fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level consistent with ADA guidelines at a target of 4.4–7.2 mmol/L; no titration algorithms were provided to clinicians, to mimic real‐world practice in a primary care setting. The dose of administered BI depended on the self‐monitored plasma glucose levels and occurrence of hypoglycaemia. Participants recorded the timing of their study treatment in e‐diaries. Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 were self‐administered once daily in the morning or evening, not related to food intake. IDet was self‐administered either once or twice daily, in the morning or evening as per package insert. There was no additional protocol‐defined guidance on, or sponsor oversight of, insulin dose titration. After randomization, participants were treated according to usual clinical practice, with protocol‐specified visits at 6 months (±30 days) and 12 months (±30 days). In the United States, BI analogues were obtained by participants via their clinician's prescription, which was dispensed by a pharmacy of their choice using vouchers provided by the study sponsor; in Canada, they were provided to participants at the site. Throughout, participants could continue previous background treatment, and investigators could prescribe additional (non‐insulin) anti‐hyperglycaemic drugs at their discretion in accordance with local labelling guidelines for concomitant use with a BI analogue. Any changes made to background anti‐hyperglycaemic therapy during the study were also at the discretion of the investigator.

Participants were encouraged to join a patient‐support programme (PSP). For participants randomized to Gla‐300, the COACH programme was available 18 ; those randomized to SOC‐BI were offered a PSP that may have been office‐based, hospital‐affiliated, community‐based, or provided by a payer.

Data were collected from HCP‐completed case report forms, administrative claims, e‐diaries (completed by study participants and used to document self‐monitored plasma glucose levels recommended at least once daily [morning fasting], as well as adverse events, dose changes, and hypoglycaemia and its symptoms), and participant surveys/questionnaires. As this was a pragmatic trial, there was limited study‐related interaction between participants and HCPs, but all participants were scheduled to undergo HbA1c testing at baseline and 6 months.

2.3. Endpoints and assessments

The composite primary endpoint was the proportion of participants who attained individualized HbA1c targets per 2015 HEDIS criteria at 6 months without experiencing hypoglycaemia at any time of day during the study. Individualized HEDIS HbA1c targets were <64 mmol/mol (8.0%) for participants aged ≥65 years and/or those who had any of the following conditions: coronary artery bypass surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention, ischaemic vascular disease, thoracic aortic aneurysm, chronic heart failure, prior myocardial infarction, chronic renal failure, end‐stage renal disease, dementia, blindness, or lower extremity amputation; an individualized HEDIS HbA1c target of <53 mmol/mol (7.0%) was assigned for all other participants. 15 , 17 Hypoglycaemia was defined as either documented symptomatic hypoglycaemia (blood glucose ≤3.9 mmol/L [≤70 mg/dL; ADA levels 1 + 2 definition of <3.9 mmol/L]) or a severe event (ADA level 3). 19 Individual components of the primary outcome are also reported.

Key secondary endpoints at 6 months included HbA1c target attainment without documented symptomatic (blood glucose <3.0 mmol/L [<54 mg/dL; equivalent to the ADA level 2 definition 19 ]) or severe hypoglycaemia, and change in HbA1c. Changes from baseline in FPG, weight, BI analogue dose, hypoglycaemia incidence (proportion of participants with ≥1 event), hypoglycaemia event rate (per participant‐year), and incidence of other treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were also examined.

Exploratory post hoc analyses were performed to examine the efficacy of Gla‐300 and SOC‐BI by HEDIS HbA1c target, and of Gla‐100 and IDet, and to determine the effect on the composite endpoint of participation in PSPs.

2.4. Statistical considerations

Initial sample size estimation was based on findings from EDITION 3, which showed similar glycaemic control of Gla‐300 and Gla‐100, but a lower risk of hypoglycaemia with Gla‐300. 20 A sample size of 3270 participants was estimated to provide ≥90% power to detect superiority of Gla‐300 versus SOC‐BI for the composite primary endpoint at a 5% significance level. Furthermore, data from a commercially available database were used to validate the proportion of participants anticipated to be assigned to each HEDIS target, resulting in the assumption of a 70%:30% split for HEDIS targets <53 mmol/mol (7%):<64 mmol/mol (8%). The ratio was applied to the EDITION 3 results to yield an assumption of an absolute overall (weighted average) difference in the primary endpoint of 5.5% favouring Gla‐300 for all study participants.

Following the addition of a blinded interim analysis, the sample size was increased to 3324. The interim analysis, planned to occur after 1800 participants had completed their 6‐month visit, was undertaken by an independent, multidisciplinary data monitoring committee and tested for overwhelming efficacy of Gla‐300 versus SOC‐BI for the primary endpoint at a 1% significance level; results were not communicated to the study sponsor before study completion and unblinding. It was determined that overwhelming efficacy was not met and the study would continue to completion. The revised sample size calculation for the final analysis considered a group‐sequential approach with an efficacy boundary based on a gamma (−3) alpha spending function and an overall two‐sided alpha level of 0.05, with two‐sided nominal significance levels of 0.010 and 0.046 at interim and final analysis, respectively.

Efficacy analyses were performed in randomized participants based on the intention‐to‐treat principle. For the determination of 6‐month HbA1c target attainment rates, randomized participants with missing data at 6 months were counted as not having attained their target. Odds ratios (ORs) with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the composite primary endpoint, its components, and other efficacy endpoints were determined by logistic regression analyses, with adjustments for HbA1c target, sulphonylurea use, GLP‐1RA use, and baseline HbA1c. Secondary and ad hoc endpoints were exploratory, and analyses of these endpoints are descriptive only. Changes in HbA1c, FPG, and weight from baseline to 6 months were assessed by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with treatment arm allocation as a fixed factor and randomization strata factors as potential confounders.

Safety, including incidence of hypoglycaemia events and TEAEs, was analysed in randomized participants who received ≥1 dose of study drug; participants who received >1 study drug were analysed according to the treatment they received for the longest period. Safety analyses were descriptive, with no statistical testing performed. Relative risk of hypoglycaemia with Gla‐300 versus SOC‐BI (risk ratio and corresponding 95% CI) was estimated with a log‐binomial regression model, using a log‐link function and a binomial response distribution, and adjusting for randomization strata (HbA1c target, sulphonylurea use, and GLP‐1RA use), and baseline HbA1c (continuous variable). Exposure‐adjusted rates for hypoglycaemia events were analysed with an over‐dispersed Poisson regression model with a log‐link function and treatment arm as a fixed effect, adjusting for randomization strata.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

A total of 3304 participants were randomized at 407 sites in the United States (n = 3137) and 20 sites in Canada (n = 167); 167 sites were identified in collaboration with insurance providers and the others were selected by the study sponsor based on the database analysis. Overall, 1632/1651 participants (98.8%) in the Gla‐300 and 1626/1653 (98.4%) in the SOC‐BI groups received ≥1 dose of study treatment, with 1497 (90.7%) and 1472 (89.1%) participants, respectively, completing the 6‐month treatment period (Figure S1).

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were similar in the two treatment groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline participant demographics and clinical characteristics, by HEDIS target and overall

| Target HbA1c <64 mmol/mol (8.0%) | Target HbA1c <53 mmol/mol (7.0%) | Overall population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gla‐300 (n = 777) | SOC‐BI (n = 740) | Gla‐300 (n = 874) | SOC‐BI (n = 913) | Gla‐300 (n = 1651) | SOC‐BI (n = 1653) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 66.8 (8.6) | 67.3 (8.6) | 53.0 (7.9) | 52.5 (7.9) | 59.4 (10.8) | 59.1 (11.0) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||||

| <65 years | 223 (28.7) | 198 (26.8) | 874 (100) | 913 (100) | 1097 (66.4) | 1111 (67.2) |

| 65 to <75 years | 429 (55.2) | 412 (55.7) | 0 | 0 | 429 (26.0) | 412 (24.9) |

| ≥75 years | 125 (16.1) | 130 (17.6) | 0 | 0 | 125 (7.6) | 130 (7.9) |

| Male, n (%) | 451 (58.0) | 427 (57.7) | 453 (51.8) | 495 (54.2) | 904 (54.8) | 922 (55.8) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 639 (82.2) | 606 (81.9) | 644 (73.7) | 693 (75.9) | 1283 (77.7) | 1299 (78.6) |

| Black | 107 (13.8) | 96 (13.0) | 155 (17.7) | 142 (15.6) | 262 (15.9) | 238 (14.4) |

| Asian/Oriental | 24 (3.1) | 32 (4.3) | 59 (6.8) | 63 (6.9) | 83 (5.0) | 95 (5.7) |

| Other | 13 (1.7) | 8 (1.1) | 20 (2.3) | 22 (2.4) | 33 (2.0) | 30 (1.8) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 33.1 (6.5) | 32.8 (6.9) | 34.5 (7.6) (n = 872) | 34.4 (7.5) (n = 912) | 33.9 (7.1) (n = 1650) | 33.7 (7.3) (n = 1652) |

| Screening HbA1c, mmol/mol, mean (SD) | 76 (8.7) | 76 (8.7) | 77 (8.7) | 77 (8.7) | 76 (8.7) | 77 (8.7) |

| Screening HbA1c, %, mean (SD) | 9.1 (0.8) | 9.1 (0.8) | 9.2 (0.8) | 9.2 (0.8) | 9.1 (0.8) | 9.2 (0.8) |

| Duration of diabetes, years, mean (SD) | 13.5 (8.4) | 13.0 (8.2) | 9.6 (5.8) | 9.7 (6.1) | 11.4 (7.4) | 11.2 (7.3) |

| Diseases/conditions that affected the assigned HEDIS target, n (%) | ||||||

| Any | 331 (42.6) | 296 (40.0) | 0 | 0 | 331 (20.0) | 296 (17.9) |

| Number of previous non‐insulin anti‐hyperglycaemic agents, a n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| 1 | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 7 (0.4) | 6 (0.4) |

| 2 | 375 (48.3) | 351 (47.4) | 420 (48.1) | 427 (46.8) | 795 (48.2) | 777 (47.0) |

| >2 | 397 (51.1) | 385 (52.0) | 451 (51.6) | 483 (52.9) | 848 (51.4) | 869 (52.6) |

| Duration of previous non‐insulin anti‐hyperglycaemic treatment, years, mean (SD) | 7.1 (5.8) (n = 776) | 7.1 (5.9) (n = 739) | 6.0 (4.8) | 5.9 (5.0) (n = 912) | 6.5 (5.3) (n = 1650) | 6.4 (5.5) (n = 1651) |

| Previous non‐insulin anti‐hyperglycaemic agents, n (%) | ||||||

| Biguanides | 688 (88.5) | 640 (86.5) | 831 (95.1) | 868 (95.1) | 1519 (92.1) | 1508 (91.3) |

| Sulphonylureas | 604 (77.7) | 596 (80.5) | 660 (75.5) | 660 (72.3) | 1264 (76.6) | 1256 (76.0) |

| DPP‐4 inhibitors | 353 (45.4) | 355 (48.0) | 349 (39.9) | 385 (42.2) | 702 (42.5) | 740 (44.8) |

| SGLT2 inhibitors | 185 (23.8) | 160 (21.6) | 259 (29.6) | 274 (30.0) | 445 (27.0) | 434 (26.3) |

| GLP‐1RAs | 124 (16.0) | 106 (14.3) | 161 (18.4) | 153 (16.8) | 285 (17.3) | 259 (15.7) |

| Thiazolidinediones | 95 (12.2) | 89 (12.0) | 105 (12.0) | 115 (12.6) | 201 (12.2) | 204 (12.3) |

| Glinides | 14 (1.8) | 18 (2.4) | 6 (0.7) | 8 (0.9) | 20 (1.2) | 26 (1.6) |

| Alpha‐glucosidase inhibitors | 9 (1.2) | 5 (0.7) | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 13 (0.8) | 8 (0.5) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) |

| HEDIS HbA1c target, n (%) | ||||||

| <53 mmol/mol (7.0%) | 0 | 0 | 874 (100) | 913 (100) | 874 (52.9) | 913 (55.2) |

| <64 mmol/mol (8.0%) | 777 (100) | 740 (100) | 0 | 0 | 777 (47.1) | 740 (44.8) |

Abbreviations: DPP‐4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4; GLP‐1RA, glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HEDIS, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set; SD, standard deviation; SGLT2, sodium‐glucose co‐transporter‐2; SOC‐BI, standard‐of‐care basal insulin (insulin glargine 100 U/mL or insulin detemir).

Some adults deviated from the protocol‐defined requirement for ≥2 diabetes medications.

3.2. Efficacy

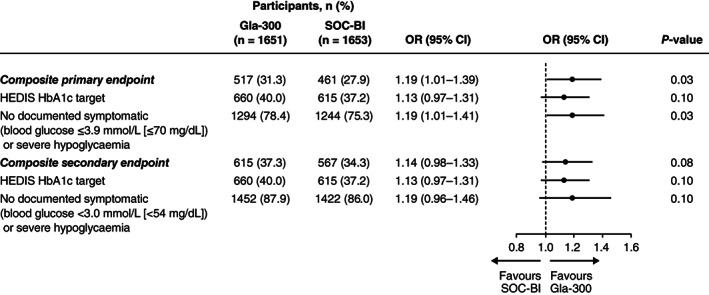

In the Gla‐300 group, a statistically significantly higher proportion of participants achieved the individualized HEDIS HbA1c targets at 6 months without documented symptomatic (blood glucose ≤3.9 mmol/L [≤70 mg/dL]) or severe hypoglycaemia versus the SOC‐BI group at any time (composite primary endpoint; 31.3% vs 27.9%, respectively; OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.01–1.39; P = 0.03 [Figure 1]). Overall, statistically significantly fewer participants randomized to Gla‐300 versus SOC‐BI had documented symptomatic (blood glucose ≤3.9 mmol/L [≤70 mg/dL]) or severe hypoglycaemia (21.6% vs 24.7%; P = 0.03).

FIGURE 1.

Achievement of the composite primary and secondary endpoints and their components, individualized glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) target (both endpoints) without documented symptomatic (blood glucose ≤3.9 mmol/L [primary endpoint; ≤70 mg/dL]; blood glucose <3.0 mmol/L [secondary endpoint; <54 mg/dL]) or severe hypoglycaemia. Overall, 164 (9.9%) and 191 (11.6%) adults in the insulin glargine 300 U/mL (Gla‐300) and standard‐of‐care basal insulin (SOC‐BI [insulin glargine 100 U/mL or insulin detemir]) groups, respectively, had missing data at 6 months and thus were counted as having not achieved the primary endpoint. CI, confidence interval; HEDIS, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set; OR, odds ratio; SOC‐BI, standard‐of‐care basal insulin

The composite secondary endpoint of HbA1c target achievement without documented symptomatic (blood glucose <3.0 mmol/L [<54 mmol/L]) or severe hypoglycaemia at 6 months was attained by 37.3% of participants in the Gla‐300 group and 34.3% in the SOC‐BI group (OR 1.14, 95% CI 0.98–1.33; Figure 1). There were no statistically significant differences between treatment groups in changes from baseline to 6 months in HbA1c, FPG, or body weight (Table 2). The mean (SD) insulin doses in the Gla‐300 and SOC‐BI groups were 0.16 (0.07) U/kg and 0.15 (0.08) U/kg, respectively, at insulin initiation, and 0.34 (0.22) U/kg (n = 1494) and 0.34 (0.22) U/kg (n = 1451), respectively, at 6 months. In the SOC‐BI group, 65.4% of participants received Gla‐100 and 34.6% IDet.

TABLE 2.

Changes from baseline to 6 months in glycated haemoglobin, fasting plasma glucose and body weight

| Gla‐300 (n = 1651) | SOC‐BI (n = 1653) | LSM difference (95% CI) | P * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c change, mmol/mol, LSM (SE) | −15 (0.3) (n = 1489) | −15 (0.3) (n = 1462) | −0.4 (−1.3 to 0.4) a | 0.32 |

| Baseline HbA1c, mmol/mol, mean (SD) | 76 (8.9) | 77 (9.0) | — | — |

| HbA1c at 6 months, mmol/mol, mean (SD) | 61 (12.7) (n = 1489) | 62 (13.0) (n = 1462) | — | — |

| HbA1c change, %, LSM (SE) | −1.4 (0.03) (n = 1489) | −1.4 (0.03) (n = 1462) | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.04) a | 0.32 |

| Baseline HbA1c, %, mean (SD) | 9.2 (0.8) | 9.2 (0.8) | — | — |

| HbA1c at 6 months, %, mean (SD) | 7.7 (1.2) (n = 1489) | 7.8 (1.2) (n = 1462) | — | — |

| FPG change, mmol/L, LSM (SE) | −2.73 (0.09) (n = 1422) | −2.81 (0.09) (n = 1371) | 0.08 (−0.16 to 0.32) b | 0.53 |

| Baseline FPG, mmol/L, mean (SD) | 11.39 (3.34) (n = 1606) | 11.63 (3.40) (n = 1601) | — | — |

| FPG at 6 months, mmol/L, mean (SD) | 8.74 (3.30) (n = 1456) | 8.69 (3.36) (n = 1401) | — | — |

| Weight change, kg, LSM (SE) | 1.0 (0.1) (n = 1496) | 1.1 (0.1) (n = 1463) | −0.1 (−0.4 to 0.2) b | 0.53 |

| Baseline weight, kg, mean (SD) | 96.9 (22.5) | 97.0 (23.4) | — | — |

| Weight at 6 months, kg, mean (SD) | 98.1 (22.7) (n = 1496) | 98.4 (23.3) (n = 1463) | — | — |

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GLP‐1RA, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; LSM, least squares mean; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error; SOC‐BI, standard‐of‐care basal insulin (insulin glargine 100 U/mL or insulin detemir).

ANCOVA model with fixed categorical effects of treatment arm, randomization strata of HbA1c target, sulphonylurea use (yes/no), GLP‐1RA use (yes/no), as well as baseline BMI (continuous) and baseline HbA1c (continuous).

ANCOVA model with fixed categorical effects of treatment arm, randomization strata of HbA1c target, sulphonylurea use (yes/no), GLP‐1RA use (yes/no), as well as baseline BMI (continuous) and baseline FPG (continuous).

P values are for descriptive purpose only.

3.3. Post hoc analyses

3.3.1. Effectiveness by HEDIS HbA1c target

Numerically, more participants randomized to Gla‐300 achieved the composite endpoints regardless of HEDIS HbA1c target (Figure S2). HbA1c changes and achievement of individualized HbA1c targets are detailed in Tables S2 and S3, respectively.

3.3.2. Effectiveness by first‐generation BI analogue subgroup

Participants prescribed IDet versus Gla‐100 were more likely to be aged ≥65 years and to have a HEDIS HbA1c target <64 mmol/mol (8.0%; Table S4). Participants treated with Gla‐300 or Gla‐100 versus IDet were more likely to achieve both composite endpoints (Figure S3) and had larger changes in HbA1c (Table S5).

3.3.3. Impact of PSPs on the primary endpoint

During the first 6 months of follow‐up, 330 participants (20.2%) in the Gla‐300 group and 144 (8.9%) in the SOC‐BI group participated in a PSP. In the Gla‐300 group, 32.1% of participants who participated in a PSP and 31.1% of those who did not participate achieved the composite endpoint. Corresponding percentages in the SOC‐BI group for PSP participants and non‐participants achieving the composite endpoint were 29.2% and 27.8%, respectively.

3.4. Safety

Overall, 28.9% of Gla‐300‐treated participants and 30.4% SOC‐BI‐treated participants had ≥1 hypoglycaemia event (risk ratio 0.95, 95% CI 0.85–1.05); 8.9% and 10.0%, respectively, experienced nocturnal hypoglycaemia (risk ratio 0.89, 95% CI 0.72–1.10; Figure S4). Exposure‐adjusted hypoglycaemia event rates were 2.41 and 2.63 events per participant‐year among participants treated with Gla‐300 and SOC‐BI, respectively (rate ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.71–1.19); corresponding nocturnal event rates were 0.45 and 0.55 events per participant‐year, respectively (rate ratio 0.82, 95% CI 0.57–1.19). Rates of TEAEs were similar in the two treatment groups (Table S6).

4. DISCUSSION

In ACHIEVE Control, a statistically significantly higher proportion of participants in the Gla‐300 group achieved their individualized HEDIS HbA1c targets without documented symptomatic (blood glucose ≤3.9 mmol/L [≤70 mg/dL]) or severe hypoglycaemia as compared to the SOC‐BI group. Further analysis of the primary composite endpoint suggests that avoidance of documented symptomatic or severe hypoglycaemia may be a benefit of Gla‐300 versus SOC‐BI. The use of a composite primary endpoint is closely linked to real‐life treatment objectives, as achieving individualized HbA1c targets while minimizing hypoglycaemia risk is an important and clinically relevant treatment goal for physicians and patients. Since >90% of US health plans use HEDIS criteria to measure treatment performance and value, 15 , 17 their use in ACHIEVE Control to individualize glycaemic targets is relevant.

Due to its unique pragmatic study design, ACHIEVE Control provides valuable data for practising clinicians that complement findings from the EDITION 3 RCT 20 and the retrospective real‐world DELIVER Naïve study. 21 The phase 3a non‐inferiority EDITION 3 study demonstrated similar efficacy of Gla‐300 and Gla‐100 in HbA1c decrease from baseline to 6 months (least squares mean difference 0.4 mmol/mol [0.04%]). In addition, in the same study, Gla‐300 was associated with lower risks of severe or confirmed nocturnal hypoglycaemia (relative risk 0.76) and severe or confirmed serious hypoglycaemia at any time of day (relative risk 0.61). 20

DELIVER Naïve, a retrospective real‐world study, demonstrated at 6 months higher proportions of adults treated with Gla‐300 versus Gla‐100 achieving HbA1c targets of <53 mmol/mol (7.0%) without hypoglycaemia (21.9% vs 17.4%; P = 0.003) and <64 mmol/mol (8.0%) without hypoglycaemia (49.1% vs 41.8%; P < 0.001). 21 Adults were also more likely to achieve HbA1c targets <53 mmol/mol (7.0%) and <64 mmol/mol (8.0%) with Gla‐300 vs Gla‐100, irrespective of hypoglycaemia. 21 Consistent with these findings, ACHIEVE Control demonstrated a significant benefit with Gla‐300 versus SOC‐BI for attainment of individualized HbA1c targets without hypoglycaemia at 6 months, and favourable trends with Gla‐300 versus SOC‐BI for individualized HbA1c target attainment, irrespective of hypoglycaemia and for absence of hypoglycaemia from baseline to 6 months.

Some important differences between ACHIEVE Control and EDITION 3 20 warrant highlighting. Besides using efficacy endpoints reflective of real‐life treatment objectives, ACHIEVE Control included a broad insulin‐naïve population, including adults who would have been ineligible for participation in EDITION 3. Furthermore, unlike EDITION 3 where participants underwent intensive titration utilizing a titration algorithm, ACHIEVE Control was carried out under real‐life conditions with titration left to the discretion of the treating physician. In addition, in EDITION 3, participants were evaluated every 4 to 6 weeks, whereas, in ACHIEVE Control, study‐related visits were limited to baseline, 6 and 12 months, and remaining interactions between participants and investigators were based on usual clinical practice.

A major strength of ACHIEVE Control is its prospective, randomized, pragmatic real‐life study design, with findings based on the treatment of a wide spectrum of insulin‐naïve adults with T2D in a real‐world setting. The participation of study investigators with no prior clinical trial experience and multiple stakeholders increases the general relevance of the study outcomes for routine clinical practice. Furthermore, ACHIEVE Control had a large study population (3305 participants) treated at more than 400 clinical sites, enhancing its relevance, translatability and scalability.

The present findings from ACHIEVE Control in insulin‐naïve participants are supported by other EDITION RCTs 22 , 23 , 24 and retrospective real‐world studies 25 , 26 , 27 performed in insulin‐experienced adults. However, the study also has a number of limitations. SOC‐BI‐treated adults could be assigned to Gla‐100 or IDet at the investigator's discretion. While this reflects clinical practice, it could have introduced channelling bias. 28 Furthermore, grouping of SOC‐BI and the lack of a titration algorithm might have introduced additional bias. Further, participants were assigned a HEDIS HbA1c target based solely on age and comorbidities, without specifically accounting for additional factors, although some of these factors are indirectly addressed through HEDIS criteria. However, any effect on outcomes should have been similar in both treatment arms. As this was a real‐life study, no continuous glucose monitoring data were obtained. In addition, 7.9% of adults in the Gla‐300 group and 9.3% in the SOC‐BI group had major/critical protocol deviations that could potentially have impacted the efficacy analyses (mainly not receiving ≥2 anti‐hyperglycaemic agents for ≥1 year [6.4% and 8.0%, respectively]).

Regarding the two main protocol amendments, the addition of a blinded interim efficacy analysis should not have affected the outcome of the study, as care was taken to preserve the integrity of the data and the statistical analysis. The inclusion of severe hypoglycaemia would have increased the number of hypoglycaemia events for both groups similarly.

Participation in PSPs was higher in the Gla‐300 group than in the SOC‐BI group (20.2% vs 8.9%), but this did not appear to influence achievement of the primary endpoint; additional analyses on the impact of PSP participation are described in the companion paper reporting the 12‐month results of ACHIEVE Control. 29

Lastly, the cost of the BI analogues for both treatment arms was covered by the sponsor, which does not mirror real‐world practice in the United States and Canada. While this limits the generalizability of the results, any effects should have been similar in both treatment arms.

Subsequent analyses of ACHIEVE Control at 12 months of follow‐up will evaluate additional clinical outcomes, healthcare‐related resource utilization, costs, and patient‐reported outcomes, providing further insights into the potential impact of Gla‐300 in real‐world practice.

In conclusion, in this pragmatic, randomized trial, which mimics real‐world practice, treatment with the second‐generation BI Gla‐300 resulted in a statistically significantly higher proportion of insulin‐naïve adults with uncontrolled T2D who achieved their individualized HEDIS HbA1c target without experiencing documented symptomatic (blood glucose ≤3.9 mmol/L [≤70 mg/dL]) or severe hypoglycaemia versus SOC‐BI. The present results complement those from prior RCTs and observational studies, supporting the efficacy and safety of Gla‐300 in insulin‐naïve adults with T2D in a real‐world setting, and add value to treatment decisions and options for patients, HCPs, payers, and decision makers.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.F.M., S.D.S., G.O., R.B., A.D., J.G. and T.S.B. designed the study. A.M.G.C., A.D. and J.G. acquired and analysed the data. All authors contributed to the data interpretation, drafting, critical review and revision of the manuscript. J.G. and A.D. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

L.F.M. reports advisory panel participation and consultancy work for Applied Therapeutics, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis. S.D.S. reports advisory panel participation and research support for Sanofi and Novo Nordisk. G.O. reports research support for Sanofi. R.B. reports advisory panel participation for AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi, research support for Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ironwood, Janssen, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi, and participation in a speakers' bureau for Amarin, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Kowa, Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. A.M.G.C., A.D. and J.G. are employees and stockholders of Sanofi. T.S.B. reports consultancy work for Lifescan, Novo and Sanofi, research support for Abbott, Capillary Biomedical, Dexcom, Diasome, Eli Lilly, Kowa, Lexicon, Medtronic, Medtrum, Novo Nordisk, REMD, Sanofi, Senseonics, Viacyte, vTv Therapeutics and Zealand Pharma, and participation in a speakers' bureau for Medtronic and Sanofi.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors received writing/editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript provided by Yunyu Huang, PhD, of Excerpta Medica BV, and Jenny Lloyd (Compass Medical Communications Ltd, on behalf of Excerpta Medica), funded by Sanofi and editorial support by Susanna Ulm, PhD, of Evidence Scientific Solutions, Inc., funded by Sanofi. This study was funded by Sanofi. Collaborators on this study were HealthCore and Comprehensive Health Insights Pharmaceuticals. These are research subsidiaries of Anthem, Inc. and Humana, respectively.

Meneghini LF, Sullivan SD, Oster G, et al. A pragmatic randomized clinical trial of insulin glargine 300 U/mL vs first‐generation basal insulin analogues in insulin‐naïve adults with type 2 diabetes: 6‐month outcomes of the ACHIEVE Control study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:2004–2012. 10.1111/dom.14152

Funding information The authors received writing/editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript provided by Yunyu Huang, PhD, of Excerpta Medica BV, and Jenny Lloyd (Compass Medical Communications Ltd, on behalf of Excerpta Medica), funded by Sanofi and editorial support by Susanne Ulm, PhD, of Evidence Scientific Solutions, Inc., funded by Sanofi. This study was funded by Sanofi. Collaborators on this study were HealthCore and Comprehensive Health Insights Pharmaceuticals. These are research subsidiaries of Anthem, Inc. and Humana, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1. Freemantle N, Chou E, Frois C, et al. Safety and efficacy of insulin glargine 300 u/mL compared with other basal insulin therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a network meta‐analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e009421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Russell‐Jones D, Gall MA, Niemeyer M, Diamant M, Del Prato S. Insulin degludec results in lower rates of nocturnal hypoglycaemia and fasting plasma glucose vs. insulin glargine: a meta‐analysis of seven clinical trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:898‐905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roussel R, Ritzel R, Boëlle‐Le Corfec E, Balkau B, Rosenstock J. Clinical perspectives from the BEGIN and EDITION programmes: trial‐level meta‐analyses outcomes with either degludec or glargine 300U/mL vs glargine 100U/mL in T2DM. Diabetes Metab. 2018;44:402‐409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shiramoto M, Eto T, Irie S, et al. Single‐dose new insulin glargine 300 U/ml provides prolonged, stable glycaemic control in Japanese and European people with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:254‐260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Becker RH, Dahmen R, Bergmann K, Lehmann A, Jax T, Heise T. New insulin glargine 300 units·mL‐1 provides a more even activity profile and prolonged glycemic control at steady state compared with insulin glargine 100 units·mL‐1. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:637‐643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bergenstal RM, Bailey TS, Rodbard D, et al. Comparison of insulin glargine 300 units/mL and 100 units/mL in adults with type 1 diabetes: continuous glucose monitoring profiles and variability using morning or evening injections. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:554‐560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Owens DR. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of insulin glargine 300 U/mL in the treatment of diabetes and their clinical relevance. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2016;12:977‐987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heise T, Hövelmann U, Nosek L, Hermanski L, Bøttcher SG, Haahr H. Comparison of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of insulin degludec and insulin glargine. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11:1193‐1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jones DS, Podolsky SH. The history and fate of the gold standard. Lancet. 2015;385:1502‐1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saunders C, Byrne CD, Guthrie B, et al. External validity of randomized controlled trials of glycaemic control and vascular disease: how representative are participants? Diabetes Med. 2013;30:300‐308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sherman RE, Anderson SA, Dal Pan GJ, et al. Real‐world evidence – what is it and what can it tell us? N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2293‐2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dagen Diabetes . ADA report. What value should clinicians place on real‐world evidence trial? https://dagensdiabetes.se/index.php/alla-senaste-nyheter/3085-ada-report-what-value-should-clinicians-place-on-real-world-evidence-trial. Accessed September 20 2019.

- 13. Janiaud P, Dal‐Ré R, Ioannidis JPA. Assessment of pragmatism in recently published randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1278‐1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zuidgeest MGP, Goetz I, Groenwold RHH, et al. Series: pragmatic trials and real world evidence: paper 1. Introduction. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;88:7‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oster G, Sullivan SD, Dalal MR, et al. Achieve control: a pragmatic clinical trial of insulin glargine 300 U/mL versus other basal insulins in insulin‐naïve patients with type 2 diabetes. Postgrad Med. 2016;128:731‐739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. American Diabetes Association (ADA) . Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(Suppl 1):S1‐S94. [Google Scholar]

- 17. National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) . HEDIS measures and technical resources. http://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/HEDISQM/Hedis2015/List_of_HEDIS_2015_Measures.pdf. Accessed July 10 2019.

- 18. Goldman JD, Gill J, Horn T, Reid T, Strong J, Polonsky WH. Improved treatment engagement among patients with diabetes treated with insulin glargine 300 U/mL who participated in the COACH support program. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9:2143‐2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Diabetes Association (ADA) . 6. Glycemic targets: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S66‐S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bolli GB, Riddle MC, Bergenstal RM, et al. New insulin glargine 300 U/ml compared with glargine 100 U/ml in insulin‐naïve people with type 2 diabetes on oral glucose‐lowering drugs: a randomized controlled trial (EDITION 3). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17:386‐394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bailey TS, Zhou FL, Gupta RA, et al. Glycaemic goal attainment and hypoglycaemia outcomes in type 2 diabetes patients initiating insulin glargine 300 units/mL or 100 units/mL: real‐world results from the DELIVER Naïve cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:1596‐1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Riddle MC, Bolli GB, Ziemen M, et al. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using basal and mealtime insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6‐month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 1). Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2755‐2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yki‐Järvinen H, Bergenstal R, Ziemen M, et al. New insulin glargine 300 units/mL versus glargine 100 units/mL in people with type 2 diabetes using oral agents and basal insulin: glucose control and hypoglycemia in a 6‐month randomized controlled trial (EDITION 2). Diabetes Care. 2014;37:3235‐3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Terauchi Y, Koyama M, Cheng X, et al. New insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus glargine 100 U/ml in Japanese people with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin and oral antihyperglycaemic drugs: glucose control and hypoglycaemia in a randomized controlled trial (EDITION JP 2). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:366‐374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhou FL, Ye F, Berhanu P, et al. Real‐world evidence concerning clinical and economic outcomes of switching to insulin glargine 300 units/mL vs other basal insulins in patients with type 2 diabetes using basal insulin. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:1293‐1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bailey TS, Wu J, Zhou FL, et al. Switching to insulin glargine 300 units/mL in real‐world older patients with type 2 diabetes (DELIVER 3). Diabetes Obes Metab. 2019;21:2384‐2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pettus J, Roussel R, Zhou FL, et al. Rates of hypoglycemia predicted in patients with type 2 diabetes on insulin glargine 300 U/ml versus first‐ and second‐generation basal insulin analogs: the real‐world LIGHTNING study. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10:617‐633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ankarfeldt MZ, Thorsted BL, Groenwold RH, Adalsteinsson E, Ali MS, Klungel OH. Assessment of channeling bias among initiators of glucose‐lowering drugs: a UK cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:19‐30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meneghini L, Blonde L, Gill J, et al. Insulin glargine 300 U/mL versus first‐generation basal insulin analogues in insulin‐naïve adults with type 2 diabetes: 12‐month outcomes of ACHIEVE control, a prospective, randomized, pragmatic real‐life clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2020; 1‐9. 10.1111/dom.14116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting Information