Abstract

Background

The intrinsic pathway factors (F) XII and FXI have been shown to contribute to thrombosis in animal models. We assessed the role of FXII and FXI in venous thrombosis in three distinct mouse models.

Methods

Venous thrombosis was assessed in mice genetically deficient for either FXII or FXI. Three models were used: the inferior vena cava (IVC) stasis, IVC stenosis, and femoral vein electrolytic injury models.

Results

In the IVC stasis model, FXII and FXI deficiency did not affect the size of thrombi but their absence was associated with decreased levels of fibrin(ogen) and an increased level of the neutrophil extracellular trap marker citrullinated histone H3. In contrast, a deficiency of either FXII or FXI resulted in a significant and equivalent reduction in thrombus weight and incidence of thrombus formation in the IVC stenosis model. Thrombi formed in the IVC stenosis model contained significantly higher levels of citrullinated histone H3 compared with the thrombi formed in the IVC stasis model. Deletion of either FXII or FXI also resulted in a significant and equivalent reduction in both fibrin and platelet accumulation in the femoral vein electrolytic injury model.

Conclusions

Collectively, these data indicate that FXII and FXI contribute to the size of venous thrombosis in models with blood flow and thrombus composition in a stasis model. This study also demonstrates the importance of using multiple mouse models to assess the role of a given protein in venous thrombosis.

Keywords: animal models, blood coagulation, factor XI, factor XII, venous thrombosis

Essentials.

FXII or FXI deficient mice were subjected to three models of venous thrombosis.

FXII and FXI contributed to venous thrombus formation in models with blood flow.

A deficiency of either FXII or FXI resulted in a similar protection against venous thrombosis.

FXII and FXI deficiency altered thrombus composition in a stasis model.

1. INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the developed world. 1 Anticoagulants serve as a mainstay therapy for the prevention and treatment of VTE. 2 However, a major limitation of current anticoagulant agents is their potential to cause life‐threatening bleeding. 2 , 3 Considerable efforts have been made to identify novel targets for anticoagulant therapies that can effectively prevent VTE while sparing critical physiological hemostatic processes. 2

The intrinsic coagulation pathway includes factors (F) XII and FXI. FXII undergoes autoactivation upon exposure to negatively charged surfaces, such as phospholipids on damaged cells, polyphosphate, kaolin, and implantable medical device materials. 4 , 5 FXIIa catalyzes the activation of FXI that, in turn, activates FIX. FIXa plays a critical role in the generation of FXa and subsequently thrombin. Amplification of thrombin generation by the intrinsic pathway is important because initiation from the tissue factor (TF)‐FVIIa complex is rapidly inhibited by tissue factor pathway inhibitor. 6

People with a genetic deficiency of FXII do not have a bleeding diathesis. 7 In contrast, FXI deficiency in humans is associated with a relatively mild bleeding diathesis that is most apparent on provocation in tissues with high fibrinolytic activity. 8 This contrasts with humans with deficiencies in FVIII (hemophilia A) or FIX (hemophilia B) that have a more severe phenotype with spontaneous episodes of bleeding. 9 Based, in part, on these clinical phenotypes, a number of agents have been developed that target FXII and FXI. 2 , 4 , 10 , 11 , 12 It is anticipated that agents targeting these factors will cause less bleeding than conventional anticoagulants. Encouragingly, results of two recent clinical trials have demonstrated that either reducing levels of FXI or inhibiting FXIa is effective in reducing the rate of asymptomatic venous thrombosis in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. 13 , 14

Both FXII and FXI have been shown to contribute to different forms of arterial thrombosis, including myocardial ischemia and stroke in preclinical models. 4 , 12 , 15 However, there are conflicting data regarding the relative contribution of FXII and FXI to venous thrombus formation in mice. Antisense oligonucleotide‐mediated knockdown of either FXII or FXI was associated with reduced venous thrombosis in the St Thomas’ model, which involves stenosis of the infrarenal section of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and temporary application of a neurovascular clip. 16 In contrast, a study reported that FXII deficiency, but not FXI deficiency, resulted in a significant reduction in thrombus formation in the IVC stenosis model of thrombosis without additional injury. 17 A recent consensus paper highlighted the potential for differences among models of venous thrombosis and the value of using multiple models with independent modes of initiation to assess the role of a given protein in venous thrombosis. 18 , 19

The goal of this study was to evaluate the contributions of FXII and FXI to venous thrombosis using genetically deficient mice in three commonly used models: IVC stenosis, IVC stasis, and femoral vein electrolytic injury.

2. METHODS

2.1. Mice

All procedures were approved by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with National Institutes of Health guidelines. FXII‐ and FXI‐deficient mice (F12 −/− and F11 −/−) on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from Dr. David Gailani (Vanderbilt University). 20 , 21 Mouse genotypes were determined by PCR at wean and confirmed at the experimental endpoint. Surgeries were conducted on 8‐ to 12‐week‐old male F12 −/−, F11 −/−, or appropriate littermate control mice in an operator‐blinded manner.

2.2. IVC stasis model

The IVC stasis model was conducted as previously described. 22 , 23 Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). A midline laparotomy was made and the bowel externalized and wrapped in wetted gauze. The IVC and adjacent aorta was mobilized by blunt dissection. Side branches were ligated using 5‐0 Prolene suture. Back branches were cauterized by diathermy. The IVC was then permanently ligated using 5‐0 Prolene suture material. Intraoperative buprenorphine was administered at a dose of 0.05 mg/kg. The peritoneum and skin were closed using 4‐0 nonabsorbable monofilament suture material. At 48 hours postthrombus induction, the thrombus was removed and weighed using a microbalance.

2.3. IVC stenosis model

Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane gas (1.5%‐3%, 1 L/min O2) for the duration of the procedure. Body temperature was maintained using a heated pad. Appropriate aseptic surgical technique was used. A midline laparotomy was made and the bowel externalized and wrapped in wetted gauze. The IVC and adjacent aorta was mobilized by blunt dissection. Side branches were first ligated using 4‐0 silk suture. The IVC and aorta were separated by sharp dissection just distal to the confluence of the left renal vein and a piece of 4‐0 silk suture material slung around the IVC. A piece of 5‐0 Prolene suture (0.1‐mm diameter) was placed on the ventral surface of the IVC and the 4‐0 silk suture was ligated tightly around the IVC with inclusion of the 5‐0 Prolene suture. The 5‐0 Prolene suture was removed resulting in stenosis of the IVC. Intraoperative buprenorphine was administered at a dose of 0.05 mg/kg. The peritoneum and skin were closed using 4‐0 nonabsorbable monofilament suture material in two layers. At 48 hours postthrombus induction, the IVC was inspected for the presence of thrombus with any resultant thrombus removed from the IVC and weighed using a microbalance.

2.4. Femoral vein electrolytic injury model

The femoral vein electrolytic injury model was conducted as previously described. 24 , 25 Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital (50 mg/kg). Rhodamine 6G (0.5 µg/g) and Alexa‐647 labeled anti‐fibrin antibody (clone 59D8, 1 µg/g) were administered intravenously through the external jugular vein. The femoral vein was exposed by a groin incision. A 1.5‐V charge was applied to the ventral surface of the femoral vein for 30 seconds using a grounded 75‐µm microsurgical needle. Accumulation of platelets and fibrin was imaged by fluorescence intravital videomicroscopy in which the field was illuminated by beam expanded 532‐ and 650‐nm laser light and fluorescent signal visualized using an operating microscope (M‐690, Wild/Leica) equipped with a digital camera (DVC‐1412, DVC Inc) connected to a camera‐synchronized shutter (UniBlitz, Chroma Technology). Data were analyzed using ImageJ software (v1.52, National Institutes of Health) and normalized fluorescent intensities calculated.

2.5. Western blotting

Western blotting of thrombus lysates was conducted as previously described. 23 Thrombi from wild‐type, F12‐/‐ and F11‐/‐mice on a C57BL/6J background were harvested, snap frozen, and stored at −80°C before processing. Thrombi were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (EMD Millipore) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, Roche) and incubated on ice for 30 minutes. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15 000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Total soluble protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce). Lysates were prepared for electrophoresis by addition of SDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and heated to 95°C for 10 minutes. Equal amounts of total soluble protein from thrombus lysates were loaded onto 4% to 20% gradient SDS polyacrylamide gels (BioRad) and separated by electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and blocked using protein‐free blocking buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Membranes were probed with anti‐CD41 (PA5‐79527, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 0.5 µg/mL), anti‐Ly6G (1A8, Lifespan Biosciences, 2 µg/mL), anti‐H3Cit (ab5103, Abcam, 1 µg/mL), anti‐H3 (ab1791, Abcam, 0.5 µg/mL), anti‐β actin (SC‐47778, Santa Cruz, 1 µg/mL), or anti‐fibrin(ogen) (A0080, Dako, 1 µg/mL) primary antibodies. Membranes were probed with Alexa‐700 and Alexa‐800 conjugated anti‐IgG secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, 0.1 µg/mL) and antigen‐antibody complexes visualized on an Odyssey imaging system (Li‐Cor Biosciences). Densitometric analysis was conducted using ImageJ software (version 1.52, National Institutes of Health).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Shapiro‐Wilk normality tests were used to assess normality of data with parametric and nonparametric tests selected as appropriate. For analysis of two groups, either unpaired Student t tests or Mann‐Whitney U tests were used. To assess differences in the incidence of thrombus formation between groups the Fisher exact test was used. Data were analyzed using Prism software (v8.2, GraphPad).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Effect of FXII or FXI deficiency on venous thrombosis in the IVC stasis and stenosis models

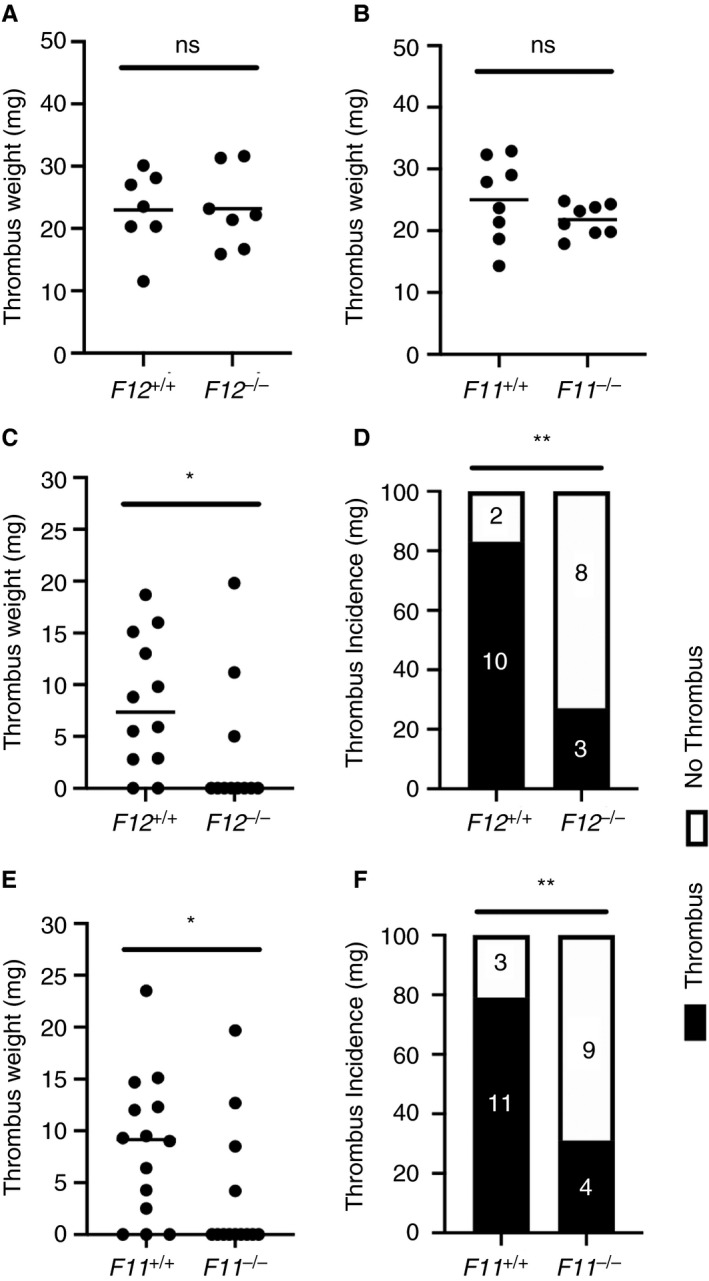

To determine the contribution of FXII and FXI to venous thrombosis, we subjected gene‐specific knockout mice to the IVC stasis and the IVC stenosis models. It is important to note the F12 −/− and F11 −/− mice have normal levels of white blood cells and platelets. 26 , 27 In the IVC stasis model, FXII deficiency did not affect thrombus weight at 48 hours postinduction (Figure 1A). Similarly, F11 −/− mice subject to the IVC stasis model demonstrated a small (12%) but nonsignificant reduction in thrombus weight at 48 hours postinduction compared with F11 +/+ controls (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of FXII and FXI deficiency on venous thrombus formation in the mouse IVC stasis and IVC stenosis models. FXII‐ and FXI‐deficient mice were subject to the IVC stasis model or IVC stenosis models of venous thrombosis and compared to wildtype littermate controls. A, Thrombus weight at 48 hours postinduction did not differ significantly between F12 −/− mice and F12 +/+ controls in the IVC stasis model (n = 7 per group). B, In the IVC stasis model, a small nonsignificant decrease in thrombus weight was observed in F11 −/− mice compared with F11 +/+ controls (n = 8 per group). ns, P > .05 Student t test. Thrombus weight data are represented as individual values with a line for the mean. C, In the IVC stenosis model, F12 −/− mice demonstrated a significant reduction in median thrombus weight at 48 hours postinduction compared with F12 +/+ controls (n = 11‐12 per group). D, A significant reduction in the incidence of venous thrombus formation in F12 −/− mice was observed compared with F12 +/+ controls. E, F11 −/− mice subject to the IVC stenosis model demonstrated a significant reduction in median thrombus weight at 48 hours postinduction compared with F11 +/+ controls (n = 13‐14 per group). F, A significant reduction in the incidence of venous thrombus formation in F11 −/− mice was observed compared with F11 +/+ controls. *P < .05, Mann‐Whitney U test, **P < .05 Fisher exact test. Thrombus weight data are represented as individual values with a line for the median

In the IVC stenosis model, in which the thrombus forms in the presence of blood flow, a significant reduction in thrombus weight at 48 hours postinduction was observed in F12 −/− mice compared with F12 +/+ littermate controls (Figure 1C). The incidence of thrombus formation was also significantly lower in F12 −/− mice compared with F12+/+ controls (3/11 vs 10/12) (Figure 1D). Thrombus weight at 48 hours postinduction was also significantly reduced in F11 −/− mice compared with F11 +/+ littermate controls subject to the IVC stenosis model (Figure 1E). Consistent with impaired thrombus formation in F11 −/− mice, the incidence of thrombus was significantly reduced compared with F11 +/+ littermate controls (4/12 vs 11/14) (Figure 1F).

3.2. Assessment of thrombus composition in the IVC stasis and stenosis models

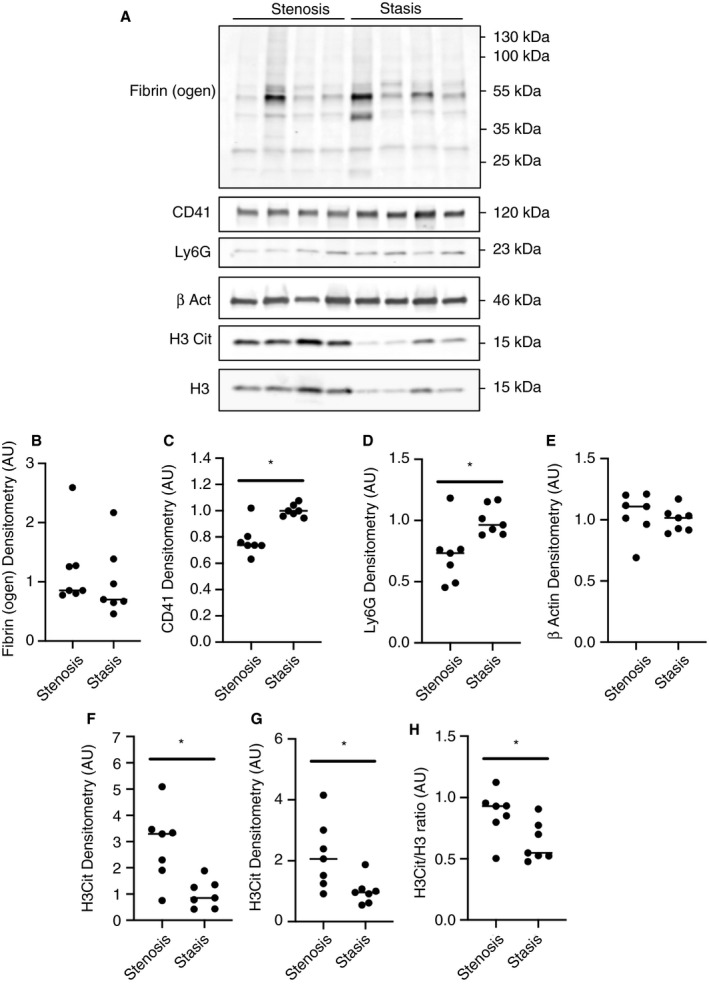

We determined if differences in thrombus composition could explain why FXII and FXI contributed to the IVC stenosis model but not the IVC stasis model. The composition of thrombi formed in wild‐type mice using the two models was assessed by western blotting (Figure 2A). Thrombi formed in the IVC stenosis and stasis models contained similar levels of fibrin(ogen) (Figure 2B). To determine the relative abundance of platelets and neutrophils, thrombus tissue lysates were immunoblotted for the cell‐specific markers CD41 and Ly6G, respectively. Surprisingly, densitometric analysis revealed that the platelet marker CD41 and the neutrophil marker Ly6G were more abundant in thrombi formed in the IVC stasis model compared to thrombi formed in the IVC stenosis model (Figure 2C and D). The relative abundance of β actin was not found to differ significantly between thrombi formed in the two models, indicating a similar degree of cellularity (Figure 2E). To assess neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation in thrombi, the abundance of citrullinated histone H3 was assessed together with histone H3 as a control. Interestingly, both citrullinated histone H3 and histone H3 were more abundant in thrombi formed by the IVC stenosis compared with the IVC stasis model (Figure 2F and G). The ratio of citrullinated histone H3 to histone H3 was also significantly increased in thrombi formed in the IVC stenosis model compared with the IVC stasis model (Figure 2H).

FIGURE 2.

Composition of thrombi formed using the mouse IVC stenosis and stasis models of thrombosis. Thrombus composition was assessed by western blotting of total soluble protein lysates from thrombi formed using the IVC stenosis and IVC stasis models of thrombosis (n = 7 per group). A, Representative western blots for fibrin(ogen), the platelet marker CD41, the neutrophil marker Ly6G, the cytoplasmic marker β Actin, citrullinated histone H3 (H3Cit), and the nuclear marker total histone H3 (H3) in thrombi formed using the IVC stenosis and IVC stasis models. Densitometric analysis of (B) fibrin(ogen), (C) CD41, (D) Ly6G, (E) β Actin, (F) H3Cit, and (G) H3 in thrombi formed in the IVC stenosis model compared with the IVC stasis model. H, The ratio of H3Cit to total H3 was significantly higher in thrombi formed in the IVC stenosis model compared with the IVC stasis model. *P < .05, **P < .01 Mann‐Whitney U test. Data represented as individual values with a line for the median

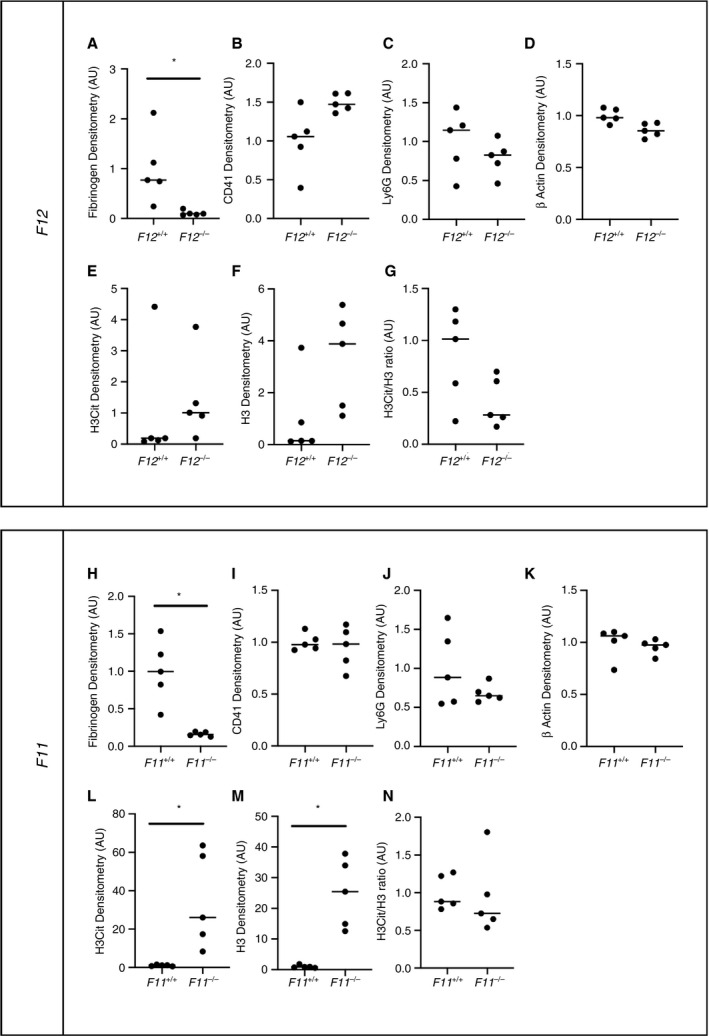

The composition of thrombi formed in F12 −/− and F11 −/− mice using the IVC stenosis and IVC stasis model was also assessed by western blotting. Consistent with findings in wild‐type mice, there was no difference in the relative abundance of fibrin(ogen) and β actin, and the relative abundance of citrullinated histone H3, total histone H3, and the ratio of citrullinated histone H3 to total histone H3 were all markedly elevated in thrombi formed using the IVC stenosis model (Figure S1). In contrast to the results with wild‐type mice, there was no significant difference in the relative abundance of CD41 or Ly6G (Figure S1).

To determine if loss of FXII or FXI altered the composition of thrombi formed using the IVC stasis model, composition of thrombi formed in F12 −/− and F11 −/− mice was compared with the respective wild‐type littermate controls. Interestingly, there was a significant decrease in levels of fibrin(ogen) in thrombi formed in F12 −/− mice and F11 −/− mice compared with their respective controls (Figure 3A and H). No significant difference in the relative abundance of CD41, Ly6G or β actin was observed in thrombi formed in F12 −/− mice compared with F12+/+ mice (Figure 3B‐D) and F11 −/− mice compared with F11+/+ mice (Figure 3I‐K). A significant increase in both citrullinated histone H3 and total histone H3 was observed in thrombi formed in F11 −/− mice compared with F11+/+ controls (Figure 3L and M). Similarly, a trend toward increased levels of citrullinated histone H3 and total histone H3 was observed in thrombi formed in F12 −/− mice compared with F12+/+ controls (Figure 3E and F). A trend toward a reduced ratio of citrullinated histone H3 to total histone H3 was observed in thrombi formed in F12 −/− mice (Figure 3G), but not F11 −/− mice (Figure 3N), when compared with the respective controls.

FIGURE 3.

Composition of thrombi formed using the IVC stasis is F12+/+ mice compared with F12 −/− mice and F11+/+ mice compared with F11 −/− mice. Thrombus composition was assessed in thrombi from F12 −/− and F11 −/− mice formed using the IVC stasis model of thrombosis by western blotting of total soluble protein lysates and compared with respective wild‐type littermate controls. Densitometric analysis of immunoblots for (A, H) fibrin(ogen), (B, I) CD41, (C, J) Ly6G, (D, K) β actin, (E, L) citrullinated histone H3, and (F, M) total histone H3 for F12 −/−, F11 −/− mice and wild‐type littermate controls. (G, N) The ratio of H3Cit to total H3 was also calculated. *P < .01 Mann‐Whitney U test. Data represented as individual values plus the median

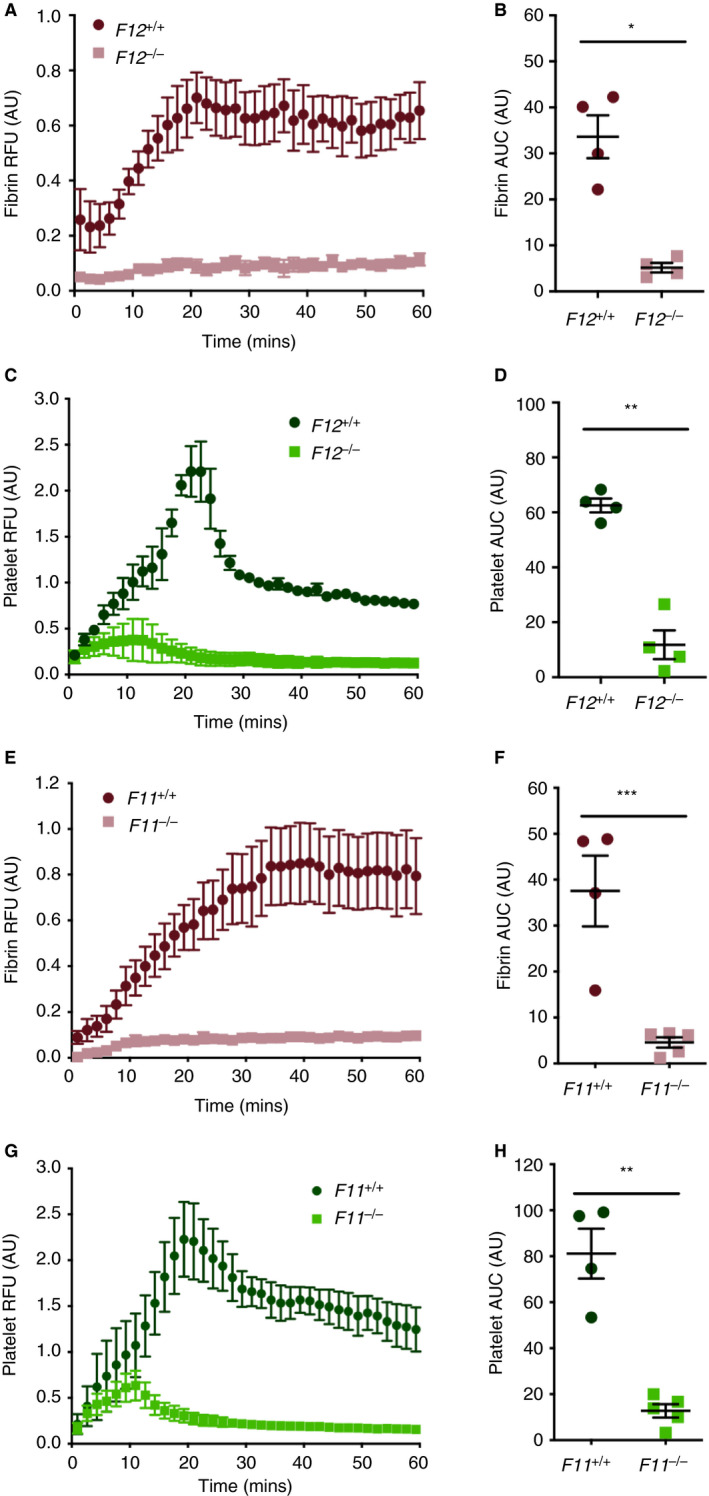

3.3. Effect of FXII and FXI deficiency on thrombus formation in the electrolytic injury model

To assess the contribution of FXII and FXI in an additional model of venous thrombosis with preserved blood flow, F12 −/−, F11 −/−, and appropriate wild‐type littermate control mice were subjected to the femoral vein electrolytic injury model. A marked reduction in the accumulation of fibrin was observed in F12 −/− mice compared with F12 +/+ littermate controls (Figure 4A). Quantification of the data by calculation of fibrin area under the curve demonstrated a significant 85% reduction in the accumulation of fibrin (Figure 4B). A significant reduction in the accumulation of platelets was also observed in F12 −/− mice compared with F12 +/+ littermate controls (Figure 4C and D). In F11 −/− mice, a marked reduction in fibrin accumulation was observed in F11 −/− mice compared with F11 +/+ littermates (Figure 4E). Quantification revealed a significant 88% reduction in fibrin accumulation was observed in F11 −/− mice compared with F11 +/+ littermates (Figure 4F). Furthermore, accumulation of platelets was also significantly reduced (Figure 4G and H).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of FXII or FXI deficiency on venous thrombus formation in the mouse femoral vein electrolytic model of thrombosis. Thrombus formation in F12 −/− and F12 +/+ controls was assessed using the femoral vein electrolytic injury model (n = 4 per group). A, A marked reduction in temporal accumulation of fibrin was observed. B, Area under the curve measurements demonstrated a significant decrease in total fibrin accumulation at the site of injury in F12 −/− mice compared with F12 +/+ controls. C, Similarly, a marked reduction in temporal platelet accumulation was observed in F12 −/− compared with F12 +/+ controls. D, Area under the curve measurements demonstrated a significant decrease in total platelet accumulation at the site of injury in F12 −/− mice compared with F12 +/+ controls. Thrombus formation in F11 −/− and F11 +/+ controls was assessed using the femoral vein electrolytic injury model (n = 4‐5 per group). E, A marked reduction in temporal fibrin accumulation was evident in F11 −/− mice compared with F11 +/+ controls. F, Area under the curve measurement demonstrated a significant reduction in total fibrin accumulation. G, A marked reduction in platelet accumulation was also observed in F11 −/− mice compared with F11 +/+ controls. H, Area under the curve measurements revealed a significant reduction in total platelet accumulation in F11 −/− mice compared with F11 +/+ controls. *P < .001, **P < .0001, ***P < .01 Student t test. Data represented at mean ± standard error of the mean

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we found a model‐dependent contribution of FXII and FXI to venous thrombosis in mice. In the IVC stasis model, neither FXII nor FXI deficiency conferred protection from venous thrombus formation. The IVC stasis model provides a strong thrombogenic insult owing to the complete ligation of the IVC, the ligation of distal lateral IVC side branches, and the cauterization of back branches. The cauterization of back branches and the full ligation of the IVC in this model likely exposes significant amounts of subendothelial TF that may trigger thrombosis. 28 Indeed, vessel wall TF, but not myeloid cell TF, has been shown to drive thrombosis in the IVC stasis model, whereas myeloid cell TF contributes to thrombosis in the IVC stenosis model. 17 , 28 , 29 It is, therefore, not surprising that a role for FXII and FXI cannot be detected in this model. Moreover, it has previously been shown that the IVC stasis model is insensitive to neutrophil depletion, platelet depletion, or inhibition of platelet activation. 30 , 31 Interestingly, however, we found that an absence of either FXII or FXI was associated with decreased levels of fibrin(ogen) and increased levels of citrullinated histone H3.

In the IVC stenosis model deletion of either FXII or FXI resulted in a comparable reduction in venous thrombus formation. The result with FXI‐deficient mice contrasts to a previous report that found no role for FXI in venous thrombus formation using genetically deficient mice subject to the IVC stenosis model (Table 1). 17 However, the absence of a phenotype in F11 −/− mice in the von Brühl et al study may be due to a number of factors that include use of a small number of F11 −/− mice in an inherently variable model and a control group of animals that were not littermates. 32 In contrast to the IVC stasis model, myeloid TF, neutrophils, NETs, and platelets have all been found to contribute to thrombus formation with IVC stenosis, a model in which the thrombus forms in the presence of blood flow and provides a milder thrombogenic insult. 17 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 34

Table 1.

Comparative effects of FXII and FXI deficiency in mouse venous thrombosis models

| Approach | Model | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ASO | St Thomas’ | Targeting FXII and FXI With High‐Level Knockdown Equally Protective | 16 |

| KO | IVC stenosis | FXII deficiency, but not FXI deficiency, protective | 17 |

| siRNA | FVEI | Targeting FXII more protective than FXI for intermediate level knockdown | 59 |

| KO | IVC stenosis | FXII and FXI deficiency equally protective |

Current study |

| KO | IVC stasis | FXII and FXI deficiency not protective |

Current study |

| KO | FVEI | FXII and FXI deficiency equally protective |

Current study |

Abbreviations: ASO, antisense oligonucleotide; FVEI, femoral vein electrolytic injury; IVC, inferior vena cava; KO, knockout; siRNA, short interfering RNA.

We determined if compositional changes in the thrombus may have contributed to the sensitivity of the IVC stenosis model to FXII and FXI. Given the important role of even relatively low shear rates for platelet activation, we hypothesized that the IVC stenosis model, which maintains low levels of blood flow at the time of induction, would support more platelet activation and incorporation than the IVC stasis model. Platelets can release and bind polyphosphate that supports activation of FXII. 35 In addition, the activated platelet surface has also been shown to promote generation of FXIIa through exposure of phosphatidylserine and to be an important surface for the activation of FXI. 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 Surprisingly, immunoblotting revealed a significantly lower relative abundance of the platelet surface marker CD41 in thrombi formed using the IVC stenosis model compared with the IVC stasis model, suggesting a relatively lower abundance of platelets. Based on this finding, it is unlikely that differences in platelet accumulation accounted for the observed sensitivity of the IVC stenosis model to FXII and FXI.

Surprisingly, the relative abundance of the neutrophil marker Ly6G was significantly lower in thrombi formed in the IVC stenosis model when compared with the IVC stasis model, indicating a lower neutrophil content. Based on the potential involvement of NET formation in FXIIa‐dependent thrombus propagation, we evaluated the extent of NET formation in the two models by measuring levels of the NET marker citrullinated histone H3 as a function of total histone H3. 23 Protein arginine deiminase 4 citrullinates histone H3 and drives NETosis, a process required for venous thrombosis in the IVC stenosis model. 33 We observed significantly higher levels of both total histone H3 and citrullinated histone H3 in thrombi formed in the IVC stenosis model than the IVC stasis model. The higher histone H3 content of thrombi from the IVC stenosis model is consistent with increased nucleated cell content. Critically, the ratio of citrullinated histone H3 to total histone H3 was significantly higher in thrombi formed using the IVC stenosis model compared with the IVC stasis model. This suggests that the amount of NET formation is higher in the IVC stenosis model. The contribution of NETs to activation of FXII remains unclear. Purified DNA has been found to promote formation of FXIIa and FXIa. 40 , 41 , 42 Isolated histones can also promote FXIIa generation in a direct or indirect manner 42 , 43 ; however, there are mixed reports on the ability of intact NETs to activate FXII. 42 , 44 It is interesting to consider if NET‐mediated activation of FXII could have contributed to the observed sensitivity of the IVC stenosis model to these factors.

The composition of thrombi formed in FXII‐ and FXI‐deficient mice using either the IVC stenosis or IVC stasis models was also assessed by western blotting. In contrast to our findings in thrombi formed in wild‐type mice, we did not observe differences in the relative abundance of CD41 or Ly6G in FXII‐ or FXI‐deficient mice. It is possible that deficiencies in FXII and FXI alter the recruitment of platelets and neutrophils that could account for this discordant observation. Importantly, however, as observed in wild‐type thrombi, a markedly higher relative abundance of citrullinated H3, total histone H3, and an increased citrullinated H3 to total H3 ratio was observed FXII‐ and FXI‐deficient thrombi formed using the stenosis model versus the stasis model. This complementary finding further reinforces the potential importance of NET formation to venous thrombus formation in the IVC stenosis model.

In addition to the ability of NETs to function as a surface for the activation of FXII, it has recently been demonstrated that FXII serves as an activator of neutrophils promoting the formation of NETs. 45 Furthermore, neutrophils express FXII that represents a distinct pool of FXII that cannot be compensated for by plasma FXII derived from hepatic expression. 45 To investigate the potential of FXII to modulate thrombus NET formation, the composition of thrombi formed using the IVC stasis model was assessed in F12 −/− mice and compared with respective F12+/+ controls. Thrombi formed in F11 −/− and F11+/+ mice were used to control for a non‐FXII specific contribution of the intrinsic pathway. Consistent with a role for FXII as an enhancer of NET formation, thrombi formed in F12 −/− mice, but not F11 −/− mice, demonstrated a reduced ratio of citrullinated H3 to total H3. Further work is required to determine if the observed effect of FXII on NET formation contributes to the observed protection of FXII‐deficient mice in intrinsic pathway sensitive models of venous thrombosis.

A deficiency of either FXII or FXI did not affect thrombus weight in the IVC stasis model. However, we observed a significant decrease in fibrin(ogen) and a significant increase in citrullinated H3 in thrombi formed in F11 −/− mice compared with controls using the IVC stasis model. Similar results were observed with F12 −/− mice. It is possible that an increase in NET formation may compensate for the reduction in fibrin(ogen). Fibrin(ogen) binds to the integrin αMβ2 on the surface of leukocytes. 46 In addition, platelet binding to neutrophils via an interaction between GP1bα and αMβ2 enhances NET formation. 47 , 48 , 49 In wild‐type mice, fibrin(ogen) binding to αMβ2 on neutrophils may limit NET formation, whereas in F12 −/− mice and F11 −/− mice, more αMβ2 is available to bind platelets with a subsequent increase in NET formation.

Thrombus formation in the IVC stenosis model takes place in the presence of residual blood flow. Experimental measurements have demonstrated that at the time of initiation blood flow through the IVC is reduced by 80% to 90% in the stenosis model compared with a complete absence of blood flow observed in the stasis model. 17 , 50 , 51 However, histological analysis indicates that in wild‐type mice, an occlusive thrombus forms by 24 hours. 17 It is possible in FXII‐ or FXI‐deficient mice that a failure to form an initial occlusive thrombus also have continued blood flow through the vessel. The retention of blood flow in the stenosed vessel may prevent the prolonged residency of procoagulant proteins and cells and subsequent amplification of thrombus formation.

To further evaluate the contribution of FXII and FXI to venous thrombosis in a flow competent model, gene‐specific knockout mice were assessed using the femoral vein electrolytic injury model of thrombosis. The femoral vein electrolytic injury model has an independent mode of initiation compared with the IVC stenosis and IVC stasis model with iron based electrolytic vascular injury driving formation of a fibrin and platelet rich thrombus. 24 Both coagulation proteases and platelets contribute to thrombus formation in this model. 24 , 25 , 52 The femoral vein electrolytic injury model has previously been shown to be sensitive to deletion of intrinsic pathway FIX. 24 , 53 Further, inhibition of polyphosphate, a potential physiological activator of FXII, markedly reduced thrombus formation in the femoral vein electrolytic injury model. 54 Importantly, deletion of either FXII or FXI impaired thrombus formation to a similar extent in this model. This is consistent with data in the IVC stenosis model and suggests that both FXII and FXI are important drivers of venous thrombosis. It is interesting to consider if the presence of residual and preserved blood flow in the IVC stenosis and femoral vein electrolytic injury models may have contributed to the observed sensitivity to FXII and FXI. In microfluidic chamber‐based studies, the formation of NETs has been found to occur in a shear stress‐dependent manner. 55 Shear stress in the IVC stenosis model and femoral vein electrolytic injury model may be an important driver of NET formation. The presence of NET components at the site of thrombosis in these models could provide a surface for activation of FXII.

There has been considerable discussion about the benefits of targeting FXII versus FXI for preventing venous thrombosis in patients. 10 In the baboon femoral arteriovenous shunt model, inhibition of FXI‐dependent activation of FIX reduced platelet deposition within the collagen‐coated portion of shunt, whereas inhibition of either FXII activation of FXI or FXII failed to reduce platelet deposition. 56 , 57 , 58 The IVC stenosis and stasis models of venous thrombosis are not titratable, making it challenging to assess the relative contribution of components of the intrinsic pathways. A single dose of antisense oligonucleotide mediated knockdown of either FXII or FXI produced similar reductions in both the St Thomas’ model and the ferric chloride IVC model. 16 Importantly, short interfering RNA mediated FXII knockdown to intermediate levels, but not high levels, was more protective than equivalent levels of FXI knockdown in the femoral vein electrolytic injury model (Table 1). 59 These findings suggest that there may be differential requirements for FXII and FXI during venous thrombosis in mice.

Our study indicates that FXII and FXI have similar contributions to three mouse models of venous thrombosis. In humans, FXI appears to play a greater role than FXII in various forms of thrombosis, including VTE. 10 In contrast to these clinical observations, FXII‐deficient mice have consistently been found to be protected in models of both venous and arterial thrombosis. 4 These discordant findings suggest a limitation of mouse models for studying the role of FXII in thrombosis because they may be overly dependent on contact activation‐mediated thrombus formation. To conclude, the results of this study have revealed model‐dependent contributions of FXII and FXI to venous thrombus formation in mice.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Steven P. Grover and Nigel Mackman designed experiments, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. Steven P. Grover, Tatianna M. Olson, and Brian C. Cooley conducted experiments, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript.

Supporting information

Fig S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Ying Zhang for excellent technical assistance and helpful comments from Dr Silvio Antoniak (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) and Dr David Gailani (Vanderbilt University). This work was supported by an AHA postdoctoral fellowship 19POST34370026 (SPG), the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute R01HL147149 (N.M), and the John C. Parker professorship (N.M.).

Grover SP, Olson TM, Cooley BC, Mackman N. Model‐dependent contributions of FXII and FXI to venous thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:2899–2909. 10.1111/jth.15037

Manuscript handled by: Scott Diamond

Final decision: Scott Diamond, 17 July 2020

REFERENCES

- 1. Wendelboe AM, McCumber M, Hylek EM, et al. Global public awareness of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(8):1365‐1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mackman N, Bergmeier W, Stouffer GA, Weitz JI. Therapeutic strategies for thrombosis: new targets and approaches. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(5):333‐352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weitz JI, Chan NC. Advances in antithrombotic therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39(1):7‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grover SP, Mackman N. Intrinsic pathway of coagulation and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39(3):331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gailani D, Geng Y, Verhamme I, et al. The mechanism underlying activation of factor IX by factor XIa. Thromb Res. 2014;133(Suppl 1):S48‐S51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Grover SP, Mackman N. Tissue factor: an essential mediator of hemostasis and trigger of thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(4):709‐725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lämmle B, Wuillemin WA, Huber I, et al. Thromboembolism and bleeding tendency in congenital factor XII deficiency–a study on 74 subjects from 14 Swiss families. Thromb Haemost. 1991;65(2):117‐121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bolton‐Maggs PH. Factor XI deficiency and its management. Haemophilia. 2000;6(Suppl 1):100‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bolton‐Maggs PH, Pasi KJ. Haemophilias A and B. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1801‐1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gailani D, Bane CE, Gruber A. Factor XI and contact activation as targets for antithrombotic therapy. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(8):1383‐1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weitz JI, Fredenburgh JC. Factors XI and XII as targets for new anticoagulants. Front Med. 2017;4:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nickel KF, Long AT, Fuchs TA, Butler LM, Renné T. Factor XII as a therapeutic target in thromboembolic and inflammatory diseases. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(1):13‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Büller HR, Bethune C, Bhanot S, et al. Factor XI antisense oligonucleotide for prevention of venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):232‐240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weitz JI, Bauersachs R, Becker B, et al. Effect of osocimab in preventing venous thromboembolism among patients undergoing knee arthroplasty: the FOXTROT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2020;323(2):130‐139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gailani D, Gruber A. Factor XI as a therapeutic target. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(7):1316‐1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Revenko AS, Gao D, Crosby JR, et al. Selective depletion of plasma prekallikrein or coagulation factor XII inhibits thrombosis in mice without increased risk of bleeding. Blood. 2011;118(19):5302‐5311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. von Brühl ML, Stark K, Steinhart A, et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. J Exp Med. 2012;209(4):819‐835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diaz JA, Saha P, Cooley B, et al. Choosing a mouse model of venous thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39(3):311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Diaz JA, Saha P, Cooley B, et al. Choosing a mouse model of venous thrombosis: a consensus assessment of utility and application. J Thromb Haemost. 2019;17(4):699‐707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pauer HU, Renné T, Hemmerlein B, et al. Targeted deletion of murine coagulation factor XII gene‐a model for contact phase activation in vivo. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92(3):503‐508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gailani D, Lasky NM, Broze GJ. A murine model of factor XI deficiency. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1997;8(2):134‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hisada Y, Ay C, Auriemma AC, Cooley BC, Mackman N. Human pancreatic tumors grown in mice release tissue factor‐positive microvesicles that increase venous clot size. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15(11):2208‐2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hisada Y, Grover SP, Maqsood A, et al. Neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps enhance venous thrombosis in mice bearing human pancreatic tumors. Haematologica. 2020;105(1):218‐225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cooley BC. In vivo fluorescence imaging of large‐vessel thrombosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(6):1351‐1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aleman MM, Walton BL, Byrnes JR, et al. Elevated prothrombin promotes venous, but not arterial, thrombosis in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(8):1829‐1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tucker EI, Gailani D, Hurst S, Cheng Q, Hanson SR, Gruber A. Survival advantage of coagulation factor XI‐deficient mice during peritoneal sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(2):271‐274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Renné T, Pozgajová M, Grüner S, et al. Defective thrombus formation in mice lacking coagulation factor XII. J Exp Med. 2005;202(2):271‐281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Day SM, Reeve JL, Pedersen B, et al. Macrovascular thrombosis is driven by tissue factor derived primarily from the blood vessel wall. Blood. 2005;105(1):192‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hampton AL, Diaz JA, Hawley AE, et al. Myeloid cell tissue factor does not contribute to venous thrombogenesis in an electrolytic injury model. Thromb Res. 2012;130(4):640‐645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. El‐Sayed OM, Dewyer NA, Luke CE, et al. Intact Toll‐like receptor 9 signaling in neutrophils modulates normal thrombogenesis in mice. J Vasc Surg. 2016;64(5):1450‐1458.e1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Payne H, Ponomaryov T, Watson SP, Brill A. Mice with a deficiency in CLEC‐2 are protected against deep vein thrombosis. Blood. 2017;129(14):2013‐2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Geddings J, Aleman MM, Wolberg A, von Brühl ML, Massberg S, Mackman N. Strengths and weaknesses of a new mouse model of thrombosis induced by inferior vena cava stenosis: communication from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(4):571‐573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martinod K, Demers M, Fuchs TA, et al. Neutrophil histone modification by peptidylarginine deiminase 4 is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(21):8674‐8679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brill A, Fuchs TA, Savchenko AS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote deep vein thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(1):136‐144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Verhoef JJ, Barendrecht AD, Nickel KF, et al. Polyphosphate nanoparticles on the platelet surface trigger contact system activation. Blood. 2017;129(12):1707‐1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bäck J, Sanchez J, Elgue G, Ekdahl KN, Nilsson B. Activated human platelets induce factor XIIa‐mediated contact activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391(1):11‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Van Der Meijden PE, Van Schilfgaarde M, Van Oerle R, Renné T, ten Cate H, Spronk HM. Platelet‐ and erythrocyte‐derived microparticles trigger thrombin generation via factor XIIa. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(7):1355‐1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zakharova NV, Artemenko EO, Podoplelova NA, et al. Platelet surface‐associated activation and secretion‐mediated inhibition of coagulation factor XII. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chaudhry SA, Serrata M, Tomczak L, et al. Cationic zinc is required for factor XII recruitment and activation by stimulated platelets and for thrombus formation in vivo. J Thromb Haemost. 2020; in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kannemeier C, Shibamiya A, Nakazawa F, et al. Extracellular RNA constitutes a natural procoagulant cofactor in blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(15):6388‐6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vu TT, Leslie BA, Stafford AR, Zhou J, Fredenburgh JC, Weitz JI. Histidine‐rich glycoprotein binds DNA and RNA and attenuates their capacity to activate the intrinsic coagulation pathway. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(1):89‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Noubouossie DF, Whelihan MF, Yu YB, et al. In vitro activation of coagulation by human neutrophil DNA and histone proteins but not neutrophil extracellular traps. Blood. 2017;129(8):1021‐1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, et al. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet‐dependent mechanisms: involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood. 2011;118(7):1952‐1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oehmcke S, Mörgelin M, Herwald H. Activation of the human contact system on neutrophil extracellular traps. J Innate Immun. 2009;1(3):225‐230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stavrou EX, Fang C, Bane KL, et al. Factor XII and uPAR upregulate neutrophil functions to influence wound healing. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(3):944‐959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Flick MJ, LaJeunesse CM, Talmage KE, et al. Fibrin(ogen) exacerbates inflammatory joint disease through a mechanism linked to the integrin alphaMbeta2 binding motif. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(11):3224‐3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sreeramkumar V, Adrover JM, Ballesteros I, et al. Neutrophils scan for activated platelets to initiate inflammation. Science. 2014;346(6214):1234‐1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jimenez MA, Novelli E, Shaw GD, Sundd P. Glycoprotein Ibα inhibitor (CCP‐224) prevents neutrophil‐platelet aggregation in sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2017;1(20):1712‐1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pulavendran S, Rudd JM, Maram P, et al. Combination therapy targeting platelet activation and virus replication protects mice against lethal influenza pneumonia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019;61(6):689‐701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Aghourian MN, Lemarié CA, Blostein MD. In vivo monitoring of venous thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(3):447‐452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Saha P, Andia ME, Modarai B, et al. Magnetic resonance T1 relaxation time of venous thrombus is determined by iron processing and predicts susceptibility to lysis. Circulation. 2013;128(7):729‐736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cooley BC, Szema L, Chen CY, Schwab JP, Schmeling G. A murine model of deep vein thrombosis: characterization and validation in transgenic mice. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94(3):498‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cooley B, Funkhouser W, Monroe D, et al. Prophylactic efficacy of BeneFIX vs Alprolix in hemophilia B mice. Blood. 2016;128(2):286‐292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Smith SA, Choi SH, Collins JN, Travers RJ, Cooley BC, Morrissey JH. Inhibition of polyphosphate as a novel strategy for preventing thrombosis and inflammation. Blood. 2012;120(26):5103‐5110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yu X, Tan J, Diamond SL. Hemodynamic force triggers rapid NETosis within sterile thrombotic occlusions. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(2):316‐329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tucker EI, Marzec UM, White TC, et al. Prevention of vascular graft occlusion and thrombus‐associated thrombin generation by inhibition of factor XI. Blood. 2009;113(4):936‐944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Geng Y, Verhamme IM, Messer A, et al. A sequential mechanism for exosite‐mediated factor IX activation by factor XIa. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(45):38200‐38209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cheng Q, Tucker EI, Pine MS, et al. A role for factor XIIa‐mediated factor XI activation in thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. 2010;116(19):3981‐3989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liu J, Cooley B, Butler J. Reduction of hepatic factor XII expression in mice by ALN‐F12 inhibits thrombosis without increasing bleeding risk. Res Prac Thromb Haemost. 2017;1:36. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1