Abstract

The epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) is a tumor-associated antigen and a potential target for tumor vaccine. The EpCAM is a cell-surface glycoprotein highly expressed in colorectal carcinomas. The objective of the present study is to develop an edible vaccine system through Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa). For the transformation, two plant expression vectors containing genes encoding for the EpCAM recombinant protein along with the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region of immunoglobulin M (IgM) and Joining (J)-chain tagged with the KDEL endoplasmic reticulum retention motif (J-chain K) were constructed. The vectors were successfully transformed and expressed in the Chinese cabbage individually using Agrobacterium. The transgenic Chinese cabbages were screened using genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in T0 transgenic plant lines generated from both transformants. Similarly, the immunoblot analysis revealed the expression of recombinant proteins in the transformants. Further, the T1 transgenic plants were generated by selfing the transgenic plants (T0) carrying EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K proteins, respectively. Subsequently, the T1 plants generated from EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K transformants were crossed to generate F1 plants carrying both transgenes. The presence of both transgenes was validated using PCR in the F1 plants. In addition, the expression of Chinese cabbage-derived EpCAM–IgM Fc × J-chain K was evaluated using immunoblot and ELISA analyses in the F1 plants. The outcomes of the present study can be utilized for the development of a potential anti-cancer vaccine candidate using Chinese cabbage.

Keywords: Agrobacterium, colorectal carcinoma, EpCAM, plant molecular biopharming, recombinant vaccine, transgenic chinese cabbage

1. Introduction

Plant expression systems, such as those in tomatoes [1,2], carrots [3], bananas [4], spinach [5], lettuce [6], and tobacco [7,8] have been established to produce valuable recombinant proteins, including therapeutic enzymes, vaccines, and antibodies. Among horticultural crops, Chinese cabbage has been recently recognized as a potential candidate to produce such valuable recombinant proteins, because it has a reasonable total soluble protein capacity relative to plant biomass [9]. In general, a large amount of soluble protein in plant biomass can provide better production of recombinant proteins, thereby enhancing the possibility of an efficient plant-based bioreactor system [10]. Chinese cabbage transformation protocols are well established for the overexpression of transgenes, which can impart resistance to plant pathogenesis [11,12,13] and tolerance to harsh environments, such as drought and salinity [14,15,16], and it can also improve physiological traits, such as tolerance to calcium deficiency [17]. There are several advantages of using Chinese cabbage for the production of therapeutic proteins. Chinese cabbage leaf biomass can be directly used in oral application without the purification of recombinant vaccines. Isolates of the targeted recombinant proteins can be easily purified from its leaf biomass. Additionally, Chinese cabbage is easy to manipulate by breeding and establishing mass seed production with self-compatibility or self-incompatibility [18]. However, the application of Chinese cabbage for therapeutic protein production has not yet been actively studied.

Among the valuable recombinant proteins expressed in plants, an epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) is a tumor-associated antigen (TAA) that has been shown to be highly expressed on cancer cells over the last several decades and expressed using diverse heterologous expression including plants such as Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris subsp. Vulgaris), Nicotiana tabaccum, and N. Benthamiana [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Plants have glutaminyl cyclases to catalyze the formation of pyroglutamic acid at the N-terminus of proteins, which is important for its immunogenicity [27,28]. Thus, it is assumed that N-terminal glutamine could be modified to pyroglutamate in diverse transgenic plants species, including Chinese cabbage. The EpCAM cancer antigenic protein can be used to prevent and inhibit cancer; hence, it is a vaccine candidate [23]. The EpCAM protein is often fused to the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region of immunoglobulin G (IgG Fc), having the advantages of Fc fusion, including enhanced protein stability, ease of application for affinity chromatography, and enhanced biofunctions [24,29,30]. Therefore, the Fc-fusion strategy has also been applied to the EpCAM-Fc fusion cancer vaccine expressed in insect and plant systems [31,32]. The plant-derived EpCAM fused to IgG Fc induced a humoral immune response in BALB/c mice [29,30]. In previous studies, the Fc fused to EpCAM originated from IgG, eventually forming IgG monomeric structures [33,34]. Recently, the fusion of Fc originating from IgA and IgM, for therapeutic recombinant proteins, has been applied to form dimeric or polymeric structures that have improved biofunctions [30,31]. In particular, IgM-like protein structures can provide hexameric or pentameric structures that have advantages, such as an ease of recognition of dendritic cells, thereby efficiently presenting an antigen for an induction of the immune response [35]. The co-expression of both IgM and Joining (J)-chain could avoid the hexameric structures that cause cytosolic responses through IgM-C1q complement-dependent cytotoxicity [36]. Indeed, such an antibody-like protein complex could have beneficial biological and chemical properties as a vaccine by targeting the antigen-presenting cells (APCs), protein–A/G-derived affinity purification, and protein in vivo stability [37]. Additionally, the Fc-fusion strategy could provide higher expression levels and stability in heterologous expression systems, eventually leading to better yield in a plant expression system [29,31,33].

In the present study, the Fc of IgM was fused to EpCAM to generate polymeric protein structures as a cancer vaccine in the Chinese cabbage expression system. Additionally, the J-chain was expressed in Chinese cabbage. Both transgenic plants carrying EpCAM fused to IgM Fc, and J-chain recombinant protein transgenes were crossed to generate F1 transgenic plants and investigate the potential of Chinese cabbage as a plant bioreactor to produce highly valuable antigen–Fc complex proteins for cancer immunotherapy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for Agrobacterium-mediated Chinese cabbage transformation and generation of transgenic plants carrying both epithelial cell adhesion molecule–immunoglobulin M fragment crystallizable (EpCAM–IgM Fc) and Joining (J)-chain K. (A) Plant expression vectors to express EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. The expected quaternary structure of EpCAM–IgM Fc in T0 transgenic plants carrying the transgene encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc is hexameric. The expected protein structure of the J-chain K in T0 transgenic plants carrying the transgene encoding J-chain K is hook-like. (B) Generation of T0 transgenic plants carrying EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K obtained from Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. (C) T1 transgenic plants with EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K obtained from self-crossing of T0 transgenic plants with EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K. Cross-fertilization between T1 transgenic plants carrying EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K transgenes after selfing of T0 plant generation. (D) F1 transgenic plants carrying both transgenes encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K obtained from crossing between T1 transgenic plants carrying transgenes encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and T1 transgenic plants carrying transgenes encoding J-chain K. The expected quaternary structure of EpCAM–IgM Fc × J-chain K in transgenic plant F1 is pentameric.

2. Results

2.1. Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation and Regeneration of T0 Transgenic Chinese Cabbage

Agrobacterium-mediated transformation was conducted to transfer genes encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc or J-chain K to Chinese cabbage (Figure 2). Three hundred hypocotyl pieces of Chinese cabbage were applied to transform plant expression vectors (pH2GW EpCAM–IgM Fc, and J-chain K) (Figure 1A,B). After co-cultivation with Agrobacterium, the hypocotyl pieces were transferred onto regeneration media (Figure 2C,D). A callus began to form at the cut ends of 30–40% of the hypocotyls within 2 weeks (Figure 2D). Adventitious shoots were observed from calli after 3–4 weeks (Figure 2D,E). The shoots were isolated from the explants and transferred onto the regeneration medium with 6 mg/L phosphinotricin (PPT) when they were at least 4–5 mm in length (Figure 2E,F). Most shoots showed vigorous regenerative growth on the new selective medium. However, some of the shoots became etiolated and died one week later. These results suggested that there were escapees from the selective medium culture. In some cases, the leaves of regenerated plants exhibited chlorosis, indicating that these plants might be chimeras.

Figure 2.

Agrobacterium-mediated Chinese cabbage transformation and generation of transgenic Chinese cabbage carrying transgenes encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K. (A) In Vitro seed germination to generate Chinese cabbage seedlings. (B) In Vitro preculture of hypocotyls in media. (C) Agrobacterium-inoculated hypocotyls incubated in in vitro regeneration media. (D) Callus generated from in vitro callus-inducing media. (E) Shoot regeneration from calli under the regeneration media. The left shows newly regenerated shoots from the callus. The right shows shoots after further growth following transfer to new regeneration media. (F) Root induction from the regenerants in root-inducing media. (G) In Vivo T0 transgenic Chinese cabbage growth after transplanting into pots with soil from the in vitro root-induced transgenic plants.

2.2. Presence of Transgenes Encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-Chain K in T0 Transgenic Plants

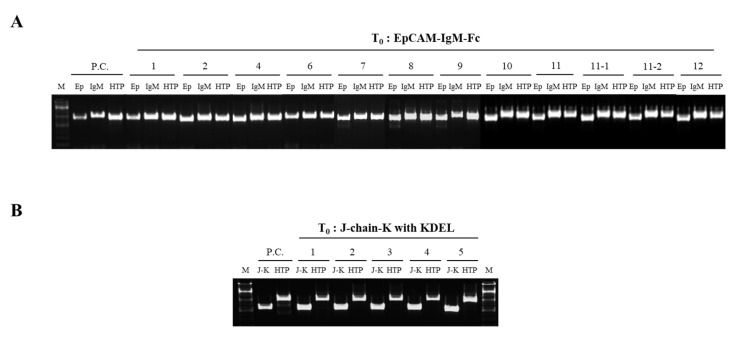

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the genomic DNA was conducted to confirm the presence of transgenes in transgenic plants (EpCAM–IgM Fc) and (J-chain K) randomly selected Chinese cabbage regenerants obtained by transforming each vector (Figure 3A,B, respectively). All tested regenerants obtained from transformations using plant expression vectors carrying the gene encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc had amplified bands at 837 bp (EpCAM), 1053 bp (IgM Fc), and 1023 bp (hygromycin phosphotransferase (HTP)) (Figure 3A). All tested regenerants obtained from transformation using the plant expression vector carrying the gene encoding the J-chain K had the expected amplified J-chain K band at 543 bp (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis to confirm the transgenes encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K in T0 transgenic lines. (A) Transgenic lines (#1–12) carrying the transgene encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc were tested by PCR using three different primer sets for EP, IgM Fc, and HTP. PC is a positive control; M, size marker; Ep, EpCAM (837 bp); IgM, Fc of IgM (1053 bp); HTP, hygromycin phosphotransferase (1023 bp); non-transgenic plant (NT). (B) Transgenic lines (#1–5) carrying a transgene encoding J-chain K. J-K, J-chain fused to KDEL endoplasmic reticulum retention signal; J-K, J-chain K (543 bp); hygromycin phosphotransferase (HTP) (1023 bp); non-transgenic plant (NT).

2.3. Expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc in T0 Transgenic Plants

Expression of the EpCAM–IgM Fc protein in leaf tissues of transgenic plants was analyzed using Western blotting (Figure 4). In the IgM Fc detection immunoblot, all randomly selected transgenic lines (2,6,7,9,11) showed an approximately 75 kDa protein band similar to that of the positive control (Figure 4A black arrowhead). In the EpCAM detection immunoblot, all lines (2,6,7,9,11) of transgenic plants showed the expected bands for EpCAM–IgM Fc (Figure 4A) with an EpCAM–IgM Fc-sized protein band (Figure 4B white arrowhead). No band was observed in the non-transgenic plants (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Immunoblot analysis to confirm the expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc in T0 transgenic lines. (A) T0 transgenic plants #2, 6, 7, 9, and 11 were tested by goat anti-IgM Fc µ-chain conjugated to HRP. M, protein marker; +, tobacco plant EpCAM–IgM Fc as a positive control; −, non-transgenic plant as a negative control. (B) T0 transgenic plants #2, 6, 7, 9, and 11 were tested by mouse anti-human EpCAM as a primary first antibody and goat anti-mouse IgG 2a heavy chain conjugated to HRP as a secondary antibody. M, protein marker; +, tobacco plant EpCAM–IgM Fc as a positive control (50 ng); −, non-transgenic plant as a negative control; hygromycin phosphotransferase (HTP).

2.4. Presence of Transgenes Encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-Chain K in T1 Transgenic Plants

The T0 transgenic line #2, with the highest expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc, was self-crossed to generate a T1 line #2 (Figure 1; Figure 4). PCR was performed for the presence of transgenes in eight (EpCAM–IgM Fc) T1 plants (Figure 5). All tested T1 plants obtained from the transformation using the plant expression vector carrying the gene encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc had the expected amplified bands at 837 bp (EpCAM), 1053 bp (IgM–Fc), and 1023bp (HTP) (Figure 5A). In the transgenic plant carrying the J-chain K transgene, the transgenic line 1 was self-crossed to generate T1. Transgenic plants in T1 carrying the J-chain K transgene were randomly selected for PCR testing (Figure 5B). All of the tested T1 plants obtained from selfing had the expected amplified band at 543 bp (J-chain K) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis to confirm the transgenes encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K in the T1 transgenic lines. (A) T1 transgenic lines (#2–9, 2–14, 2–17, 2–20, 2–21, 2–23, 2–25, and 2–27) carrying the transgene encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc were tested by PCR using three different primer sets for EP, IgM Fc, and HTP. PC is a positive control; M, size marker; Ep, EpCAM (837 bp); IgM, Fc of IgM (1053 bp); HTP, hygromycine phosphotransferase (1023 bp); non-transgenic plant (NT). (B) T1 transgenic lines (#1–1, 1–2, 1–3, 1–4, and 1–5) carrying the transgene encoding J-chain K. J-K, J-chain fused to KDEL endoplasmic reticulum retention signal; J-K, J-chain K (543 bp); hygromycin phosphotransferase (HTP) (1023 bp); non-transgenic plant (NT).

2.5. Expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc in T1 Transgenic Plants

In all tested T1 transgenic lines, expression of the EpCAM–IgM Fc protein was confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 6). In the IgM Fc detection immunoblot, all tested transgenic lines (#2–9, 2–14, 2–28, 2–35, and 2–54), except for lines 2–17, showed a strong protein band (75 kDa) (Figure 6A). In the EpCAM detection immunoblot, the #2–9, 2–14, and 2–21 lines showed the strongest protein band density, whereas the #2–17, 2–23, and 2–27 lines had weak protein bands (75 kDa) (Figure 6B). Additionally, 50 kDa size bands were also observed in all lines, including the non-transgenic control line. No band was observed in the non-transgenic plants (Figure 6). It is speculated that the 50 kDa protein bands are Rubisco proteins, which are often detected in plant total soluble proteins.

Figure 6.

Immunoblot analysis to confirm the expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc in representative T1 transgenic lines. (A) T1 transgenic plants #2–9, 2–14, 2–17, 2–21, 2–23, and 2–27 were tested by goat anti-human IgM Fc µ-chain conjugated to HRP. M, protein marker; +, tobacco plant EpCAM–IgM Fc as a positive control; −, non-transgenic plant as a negative control. (B) T1 transgenic plants #2–9, 2–14, 2–17, 2–21, 2–23, and 2–27 were tested by mouse anti-human EpCAM as the first antibody and goat anti-mouse IgG 2a conjugated to HRP as the second antibody. M, protein marker; +, tobacco plant EpCAM–IgM Fc as a positive control (50 ng); −, non-transgenic plant as a negative control; hygromycin phosphotransferase (HTP).

2.6. Presence of Transgenes Encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-Chain K in F1 Transgenic Plants Obtained between EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-Chain K T1 Plants

The F1 plants were obtained from crossing EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K T1 plants. The presence of transgenes encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K was confirmed in the F1 plants using PCR. In randomly selected F1 plants, all tested F1 lines showed the presence of the transgenes EpCAM (837 bp), IgM Fc (1053 bp), and J-chain K (543 bp), except for M209-8, in which only the J-chain K gene was detected without the EpCAM and IgM Fc genes (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis to confirm the transgenes encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K in F1 transgenic lines obtained by crossing between T1 EpCAM Fc transgenic plants (#2) and T1 J-chain transgenic lines (#1). F1 transgenic lines (#M209-1, M209-2, M209-3, M209-4, M209-5, M209-6, M209-7, M209-9, and M209-10) carrying a transgene encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc were tested by PCR using three different primer sets for Ep, IgM Fc, and HTP. positive control (PC); size marker (M); Ep, EpCAM (837 bp); IgM, Fc of IgM (1053 bp); J-K, J-chain K (543 bp); non-transgenic plant (NT); hygromycine phosphotransferase (HTP).

2.7. Expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc in F1 Transgenic Plants Obtained by Crossing EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-Chain K T1 Plants

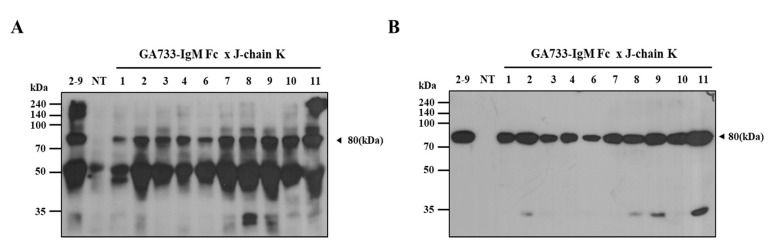

In the F1 transgenic lines with positive PCR results for EpCAM, IgM Fc, and J-chain K transgenes, the expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc was confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 8A). In the IgM Fc detection immunoblot, all tested F1 transgenic lines (#1–9) showed the 75 kDa size protein band. Furthermore, in the EpCAM detection immunoblot, all tested F1 transgenic lines (#1–9) showed the 75 kDa size protein band (Figure 8B). No bands were observed in the non-transgenic plants (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Immunoblot analysis to confirm the expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc in representative F1 transgenic lines. (A) F1 transgenic plants M209-1–209-10 were tested by goat anti-IgM Fc µ-chain conjugated to HRP. protein marker (M); +, tobacco plant EpCAM–IgM Fc as a positive control; − non-transgenic plant as a negative control. (B) F1 transgenic plants M209-1–209-10 were tested by mouse anti-human EpCAM as the first antibody and goat anti-mouse IgG 2a conjugated to HRP as the second antibody. 2–9, T1 transgenic plant #2–9 (Figure 6); +, tobacco plant EpCAM–IgM Fc as a positive control (50 ng); −, non-transgenic plant (NT) as a negative control; hygromycin phosphotransferase (HTP).

2.8. Binding Affinity of the Anti-IgM Fc µ-Chain Antibody to Chinese Cabbage-Derived EpCAM-IgM Fc × J-Chain K (EpCAM-IgM FcC × J-Chain KC).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was conducted for the recognition of Chinese cabbage-derived EpCAM–IgM FcC × J-chain KC using an anti-IgM Fc µ-chain antibody (Figure 9). In the anti-IgM Fc µ-chain antibody treatment group, both EpCAM–IgM FcT × J-ChainKT and EpCAM–IgM FcC × J-ChainKC showed high absorbance levels (0.367 and 0.315, respectively), whereas EpCAM–IgG FcT had almost no absorbance signal (0.02) (Figure 9). However, in the anti-IgG Fc treatment group, both EpCAM–IgM FcT × J-ChainKT and EpCAM–IgM FcC × J-ChainKC showed almost no absorbance signal (0.01 and 0.018, respectively), whereas EpCAM–IgG FcT showed an absorbance signal (0.165) (Figure 9). In the 1X PBS treatment group, all three samples lacked an absorbance signal (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to confirm binding interaction between anti-IgM Fc µ-chain antibody and EpCAM–IgM Fc × J-ChainK purified from F1 transgenic Chinese cabbage plant. Each ELISA plate well was coated with 10 ng of the purified Chinse cabbage-derived EpCAM–IgM Fc × J-ChainK (EpCAM–IgM FcC × J-ChainKC), tobacco-derived EpCAM–IgM Fc × J-ChainK (EpCAM–IgM FcT x J-ChainKT), or tobacco-derived EpCAM–IgG Fc (EpCAM–IgG Fc T). Each anti-IgM Fc µ-chain antibody and anti-IgG Fc antibody conjugated to HRP was applied to the coated well. Error bars indicate standard deviation (* p < 0.05); hygromycin phosphotransferase (HTP).

3. Discussion

This study demonstrated the successful expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc as anti-colorectal cancer IgM Fc fusion antigenic proteins, creating a candidate for a cancer vaccine in transgenic T0 and T1 Chinese cabbage, including F1 plants from a crossing between EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K T1 transgenic plants. Transgenic Chinese cabbage expressing EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K were obtained from Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. PCR analysis revealed that all tested T0 transgenic plants carrying EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K transgenes had PCR bands of both transgenes, indicating that these genes were properly embedded in the plant genome. Western blotting showed variable expression of the EpCAM–IgM Fc transgene in the T0 transgenic plants. In EpCAM–IgM Fc, among the tested T0 transgenic plants, transgenic line #2 had the highest level of EpCAM–IgM Fc. Thus, EpCAM–IgM Fc transgenic line #2 was selected for self-crossing to generate T1 plants. Regarding the J-chain K, according to Western blot analysis, its expression was not observed in the T0 transgenic plants.

In both EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K T1 transgenic plants, the existence of EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K transgenes was confirmed by PCR, respectively. However, Western blotting revealed that only the EpCAM–IgM Fc protein expression was detected in the T1 plants, and the J-chain K protein was not detected. It appeared that J-chain protein expression is difficult to detect. Currently, there are no reports demonstrating J-chain expression in transgenic plants. However, the function of the J-chain is active when it is co-expressed with IgM or immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies [36]. Despite a barely detectable J-chain protein level, it has vital activity when it assembles with IgM Fc or IgA Fc to generate pentameric or dimeric structures, respectively [38].

The T1 transgenic line highly expressing EpCAM–IgM Fc proteins was selected to cross with the T1 transgenic line carrying the J-chain K transgene to generate F1 plants carrying two transgenes. Since transgenic Chinese cabbage plants have the ability of self-fertilization and cross-fertilization, this crop has been efficiently bred to build useful characteristics in terms of growth physiology, taste, and disease resistance [39,40,41]. In this study, we used self- and cross-fertilization of Chinese cabbage to obtain the F1 plants having two different transgenes encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K. The immunoglobulin Fc-fusion protein is the protein linked to the immunoglobulin Fc fragment. The Fc-fused proteins obtain beneficial biological and pharmacological effects from the Fc fragment [42,43]. The Fc fragment remarkably enhances the plasma half-life of their fused proteins or peptides through its FcRn interaction, eventually prolonging their therapeutic activities [43]. Additionally, the Fc fragment interacts with Fc receptors on immune cells to provoke antigen presentation, inducing immune responses [44,45]. Furthermore, regarding protein expression, the Fc-fused proteins in general exhibit better protein expression [29]. The Fc-fused protein can be purified by Protein-A affinity chromatography [42]. In general, there are three major Ig Fc fragment forms, IgG, IgA, and IgM. The IgG and IgA-Fc fused proteins can be assembled in monomeric and dimeric forms, respectively [46]. The IgM Fc can be assembled to polymerize through disulfide bonding localized to the junction portions of CH2 and CH3 of the Fc fragment [35]. The J-chain has important functions in the assembly with IgA and IgM, acting as a glue between the Fc regions of each antibody [35]. In IgA, the J-chain enhances the dimerization of IgA and its secretion process [47]. In IgM, J-chain forms the pentameric structure from the hexameric structure [35]. The pentameric structures are less effective at activating complements than the hexameric structures, reducing damage to epithelial membranes. The J-chain on IgM might sterically hinder the binding of complement component 1q (C1q) and thereby decrease the cytolytic activity of pentameric IgM [48]. Therefore, the J-chain should be co-expressed with the IgM–Fc fusion anti-colorectal cancer vaccine candidate. The two expression cassettes can be combined and transferred into one Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. However, in this study, each transgene was individually transferred to each Chinese cabbage plant, and these plants were successfully cross-fertilized to obtain both transgenes. To confirm whether an anti-human IgM Fc µ-chain antibody can recognize Chinese cabbage-derived EpCAM–IgM Fc × J-chain K, an ELISA analysis was conducted. The binding reaction between EpCAM–IgM Fc × J-chain K and the anti-human IgM Fc µ-chain antibody showed an absorbance signal indicating that the EpCAM–IgM Fc × J-chain K was structurally formed to be recognized by the anti-IgM Fc µ-chain antibody. In previous studies, EpCAM alone and fused with IgG Fc have been expressed in diverse plants [26,27,28], however, the IgM–Fc fused EpCAM is the first report in this study. In this current study, a glycosylation study with the EpCAM–IgM × J-chain K was not conducted, which affects its immunogencitiy. It has been reported that the Brasscia species has glycosylation apparatus for protein glycosylation [49,50]. In the current study, it is speculated that the EpCAM–IgM Fc assembled with J-chain K, retaining it inside endoplasmic reticulum (ER), harboring mainly an oligomannose type. Thus, in the future, glycosylation should be further investigated.

All considered, we confirmed that each EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K transgene expression cassette was successfully transferred to the Chinese cabbage, and cross-fertilization between both transgenic plants carrying one of the transgenes generated F1 transgenic seedlings carrying both transgenes. These results revealed that both transgenes were stably inserted, and the EpCAM–IgM Fc protein gene was expressed in F1 transgenic plants reproduced from crossing between EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K T1 transgenic plants. Furthermore, these results suggested that two genes can co-exist through cross-breeding in Chinese cabbage T1 transgenic plants. In conclusion, the transgenic Chinese cabbage expressing EpCAM–IgM Fc can be applied to express anti-colorectal cancer IgM Fc fusion recombinant vaccine candidate proteins.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Expression Vector and Agrobacterium Strain

The gene encoding the human EpCAM protein (Thr17-Lys265, GenBank accession no. BC014785) was fused to the gene encoding human IgM Fc polypeptides (Leu103-Tyr453, GenBank accession no. X57086) to construct the EpCAM–IgM Fc fusion protein, and this was cloned under the CaMV promoter in the plant expression vector pRCV2 to generate pRCV2 EpCAM–IgM Fc carrying the hygromycin phosphotransferase (hpt) gene for Chinese cabbage (B. rapa L. ssp. pekinensis) transformation [45]. The 30 amino acids (MATQRRANPSSLHLITVFSLLAAVVSAEVD) as an ER signal peptide from Nicotiana plumbaginifolia was fused to N-terminus of the cleavage site (Thr17-Ala23). Chinese cabbage was transformed with the plant expression vector pRCV2 EpCAM–IgM Fc (Figure 1A). This vector was constructed by ligating pCAMBIA 1301 with pBluescript II KS (+) (Stratagene, San Diego, CA, USA) according to a previous study [12]. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA 4404 carrying pRCV2 EpCAM–IgM Fc was applied for plant transformation. Agrobacteria were grown in a yeast extract peptone (YEP) medium.

4.2. Plant Material and Preparation

Chinese cabbage Seoul (Dong-bu Seed, Seoul, Korea) was used for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation to express EpCAM–IgM Fc and the J-chain tagged with the KDEL endoplasmic reticulum retention motif (J-chain K) (Figure 1B). The seeds were submerged in 70% ethanol for 1 min. Then, the seeds were vigorously shaken in 30% commercial Clorox (The Clorox company, Oakland, CA, USA) (1.6% hypochlorite) plus 0.1% Tween-20 (USB, Cleveland, OH, USA) for 20 min. Then, they were rinsed three times with water. The seeds were germinated on an MS medium [51] and cultivated in vitro to grow hypocotyls 4–5 cm long for 7 days under a 16 h photoperiod. Following this, the hypocotyls were dissected, avoiding the shoot apex, and quickly cut into 7–8 mm segments for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

4.3. Transformation and Selection Procedures

One mL of Agrobacterium cell stock was cultured in 50 mL of a YEP medium containing kanamycin (50 mg/L) and acetosyringone (5 mg/L) until an optical density (OD) 600 value of 1.0 was obtained. The Agrobacterium cells were pelleted and washed. Then, they were resuspended in 50 mL of the YEP medium. Agrobacterium cells were applied to infect hypocotyl explants by immersing them in the bacterial inoculum for 10 min (Figure 1B). The hypocotyl explants were blotted on sterile filter paper and placed on a co-cultivation medium containing acetosyringone (5 mg/L) at pH 5.2–5.7. After 3 days of co-cultivation, the explants were washed with an MS liquid medium supplemented with cefotaxime (200 mg/L) and transferred to an MS selection medium containing 3% sucrose, IBA (4 mg/L), NAA (3 mg/L), AgNO3 (4 mg/L), acetosyringone (5 mg/L), cefotaxime (200 mg/L), hygromycin (10 mg/L), and 0.8% plant agar (pH 5.6). After cultivation for 3 and 8 weeks, the number of calli and shoots that formed on the explants were determined, respectively (Figure 1B). Then, the regenerated shoots were transferred to a rooting medium that consisted of 1/2-strength MS medium, 3% sucrose, cefotaxime (200 mg/L), and 0.7% plant agar (pH 5.8).

4.4. PCR Amplification from Genomic DNA of Plant Leaf

To confirm the existence of transgene encoding EpCAM–IgM Fc, genomic DNA was prepared from the fresh leaves of transgenic and non-transgenic Chinese cabbage plants according to the DNA extraction kit (RBC Bioscience, Taipei, Taiwan) using the mini-prep method and protocol. DNA concentration was measured using a NanovueTM plus spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare, Boston, MA, USA) and adjusted to 20 ng/μL, and the DNA was used for PCR amplification. The status of transgenic plants was confirmed by PCR using HTP (hygromycine) and target gene (EpCAM, IgM, and J-Chain K) specific primers. The reaction solution for PCR analysis contained 20 ng of gDNA, 5.0 μL of Takara buffer mixture buffer (Takara, Kusatsu, Japan), 1.0 μL each of 10 pmol/μL of primer set, and autoclaved distilled water, to reach a total volume of 20 μL. The primer set for EpCAM (837 bp, forward primer (F)-GCA GGC TAT GGC TAC TCA ACG AAG G/reverse primer (R)-CTC GAG TTT TAG ACC CTG CAT TGA G), IgM (1053 bp, F-CTC GAG CTT CCA GTG ATT GCT GAG C/R-CTC GAG TCA GTA GCA GGT GCC AGC TGT G), J-chain K (543 bp, F-GCA GGC TAT GGC CAA GAA CCA TTT GC/R-AGT TCA TCT TTG TCA GGA TAG CAG G), and hygromycine (HPT, 1023 bp, F-CTA TTC CTT TGC CCT CGG ACG GC/R-ATG AAA AAG CCT GAA CTC ACC GCG ACG) genes were used for DNA amplification to confirm the presence of the transgene in the plants. The PCR reaction was performed as follows: denaturation at 95 ℃ for 10 min in the beginning, a repeated cycling step of denaturation at 95 ℃ for 1 min, annealing at 56 ℃ for 40 s, and extension at 72 ℃ for 1 min (35 times). This was followed by a final denaturation at 72 ℃ for 10 min. A non-transgenic Chinese cabbage plant was used as a negative control, whereas plant expression vectors containing the EpCAM–IgM Fc and J-chain K genes were used as positive controls.

4.5. Western Blot

To confirm the expression of EpCAM–IgM Fc in transgenic Chinese cabbage, 100 mg of leaf tissue was harvested from in vitro tissue culture and homogenized to generate leaf extracts in 1× PBS. A volume of 20 μL of leaf extract samples (100 mg of leaf/300 μL) mixed with 5 μL of protein loading buffer (1 M Tris-HCl, 50% glycerol, 10% SDS, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue) was loaded on 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membrane was incubated in blocking buffer (5% skim milk (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) in Tris-Buffered Saline (TBS) plus 0.5% (v/v) Tween 20). The blot was incubated for 1 h 30 min at room temperature (RT) with either mouse anti-human EpCAM antibody # MAB960-500 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) diluted in blocking buffer at 1:500 or goat anti-human IgM Fc µ-chain conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) diluted in blocking buffer at 1:5000 and then incubated for 1 h and 30 min at RT with a secondary antibody goat anti-mouse IgG 2a heavy chain conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted in blocking buffer at 1:5000. The goat anti-human IgM Fc µ-chain antibody recognized the IgM Fc portion of EpCAM–IgM Fc, whereas the anti-human EpCAM antibody detected EpCAM. Protein bands were visualized by exposing the membrane to X-ray film (Fuji, Tokyo, Japan) using a chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce). Non-transgenic plants and tobacco-derived human EpCAM–IgM Fc (50 ng) [52] were used as negative and positive controls, respectively.

4.6. Cross-Fertilization

After T0 transgenic plant validation by PCR and Western blot analysis, the transgenic plantlets (T0) with well-developed roots were transplanted into 10 cm pots containing soil and transferred to a glasshouse at the National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science (NIHHS), Wanju, Korea from 2015 to 2017 (Figure 1B). The plants were grown under normal daylight conditions with a set temperature of 22 °C and 60–70% relative humidity (RH). The T0 plants were grown in 2015 and selfed to produce seeds (T1). In 2016, the T1 seeds were sown and the plants were grown for 4–6 weeks with vernalization treatment (Figure 1C). The T1 plants containing the EpCAM–IgM Fc genes were crossed with the T1 plants with J-chain K during the blooming stage for the generation of the F1 transgenic lines in 2017. The crossing resulted in the generation of the F1 transgenic line (Figure 1D).

4.7. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The Maxisorp 96-well immuno plates (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were coated and incubated overnight at 4 ℃ with 10 ng per well of purified tobacco plant-derived EpCAM–IgG Fc (EpCAM–IgG FcT) [44], tobacco plant-derived EpCAM–IgM Fc (EpCAM–IgM FcT) × J-Chain KT [48], and Chinese cabbage-derived EpCAM–IgM Fc (EpCAM–IgM FcC) × J-Chain KC proteins diluted in 0.05 M carbonate/bicarbonate buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). After overnight incubation, the plates were washed with 1X PBS plus 0.5% (v/v) Tween 20 (1X PBS-T) four times and blocked with 5% skim milk (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in 1X PBS-T for 1 h at RT. Then, the plates were treated with rabbit anti-human IgG Fcγ antibody conjugated to HRP (Jackson Immunolab, West Grove, PA, USA) or goat anti-human IgM Fc µ-chain antibody conjugated to HRP (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) diluted 1:5000 in 1X PBS-T or 1X PBS and incubated for 2 h at RT. After washing four times with 1X PBS-T, the plates were detected using 3,3′,5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate and TMB stop solution (SeraCare, Milford, CT, USA). The plates were read using an Epoch Microplate Spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) at 450 nm.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis consisted of using Student’s t-test to determine the differences in absorbance of each group (EpCAM–IgG FcT, EpCAM–IgM FcT × J-Chain KT, and EpCAM–IgM FcC × J-Chain KC) using Microsoft Excel software (Microsoft Office Excel; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The difference between each group (EpCAM–IgG FcT, EpCAM–IgM FcT × J-Chain KT, and EpCAM–IgM FcC × J-Chain KC) was compared for statistical significance at 0.05 and 0.01 probabilities (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Abbreviations

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| EpCAM | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| Fc | Fragment crystallizable |

| IgM | Immunoglobulin M |

| J-chain | Joining-chain |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| MS | Murashige and skoog |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| TAA | Tumor-associated antigen |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-R.L., K.K., and D.-S.K.; methodology, Y.-R.L., C.-Y.L., J.K., H.-E.L., S.L., K.K., and D.-S.K.; software, S.R.P., S.L., H.-E.L., and C.-Y.L.; validation, Y.-R.L., K.K., and D.-S.K.; formal analysis, Y.-R.L., C.-Y.L., S.L., J.-P.H., and H.-E.L.; investigation, Y.-R.L., K.K., and D.-S.K.; resources, Y.-R.L., and C.-Y.L.; data curation, Y.-R.L., C.-Y.L., S.R.P., S.L., K.K., and D.-S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-R.L., D.-S.K., and K.K.; writing—review and editing, Y.-R.L., S.R.P., S.L., K.K., and D.-S.K.; visualization, Y.-R.L., C.-Y.L., S.R.P., S.L., S.K., and K.K.; supervision K.K. and D.-S.K.; project administration, J.K., K.K., and D.-S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of “Cooperative Research Program for Agriculture Science and Technology Development (Project No. PJ01343703)” Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pogrebnyak N., Golovkin M., Andrianov V., Spitsin S., Smirnov Y., Egolf R., Koprowski H. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) S protein production in plants: Development of recombinant vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9062–9067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503760102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantor M., Sestras R., Chowdhury K. Transgenic tomato plants expressing the antigen gene PfCP-2.9 of Plasmodium falciparum. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2013;48:73–79. doi: 10.1590/S0100-204X2013000100010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaaltiel Y., Tzaban S., Fiks N., Tekoah Y., Aviezer D., Gingis-Velitski S. Plant-based oral delivery of β-glucocerebrosidase as an enzyme replacement therapy for Gaucher’s disease. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015;13:1033–1040. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma M., Sood B. A banana or a syringe: Journey to edible vaccines. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;27:471–477. doi: 10.1007/s11274-010-0481-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tacket C.O., Mason H.S., Losonsky G., Estes M.K., Levine M.M., Arntzen C.J. Human Immune Responses to a Novel Norwalk Virus Vaccine Delivered in Transgenic Potatoes. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;182:302–305. doi: 10.1086/315653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusibov V. Expression in plants and immunogenicity of plant virus-based experimental rabies vaccine. Vaccine. 2002;20:3155–3164. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(02)00260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shin C., Kang Y., Kim H.-S., Shin Y.K., Ko K. Immune response of heterologous recombinant antigenic protein of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) in mice. Anim. Cells Syst. 2019;23:97–105. doi: 10.1080/19768354.2019.1575904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee J.H., Park S.R., Phoolcharoen W., Eko K. Expression, function, and glycosylation of anti-colorectal cancer large single-chain antibody (LSC) in plant. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2020;14:363–371. doi: 10.1007/s11816-020-00610-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song I., Park S.-A., Han D., Lee H.K., Perlman D.H., Eko K. Expression, glycosylation, and function of an anti-rabies virus monoclonal antibody in tobacco and Arabidopsis plants. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2018;59:285–292. doi: 10.1007/s13580-018-0031-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon K.-B., Park J.-S., Park Y.-I., Song I.-J., Lee H., Cho H.S., Jeon J.H., Kim H.-S. Development of Systems for the Production of Plant-Derived Biopharmaceuticals. Plants. 2019;9:30. doi: 10.3390/plants9010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanjildorj E., Song S.Y., Yang Z.H., Choi J.E., Noh Y.S., Park S., Lim W.J., Cho K.M., Yun H.D., Lim Y.P. Enhancement of tolerance to soft rot disease in the transgenic Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. Pekinensis) inbred line, Kenshin. Plant Cell Rep. 2009;28:1581–1591. doi: 10.1007/s00299-009-0757-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J., Kang W.-H., Hwang J., Yang H.-B., Dosun K., Oh C.-S., Kang B.-C. Transgenic Brassica rapa plants over-expressing eIF(iso)4E variants show broad-spectrum Turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) resistance. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2014;15:615–626. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi D., Yang W., Tang J., Wang L., Fang Z., Liu Y., Zhuang M., Zhang Y., Yang L. High resistance of transgenic cabbage plants with a synthetic cry1Ia8 gene from Bacillus thuringiensis against two lepidopteran species under field conditions. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015;72:315–321. doi: 10.1002/ps.3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park J.-S., Yu J.-G., Park Y.-D. Characterization of a drought tolerance-related gene of Chinese cabbage in a transgenic tobacco plant. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2017;58:48–55. doi: 10.1007/s13580-017-0157-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qiu N., Liu Q., Li J., Zhang Y., Wang F., Gao J. Physiological and Transcriptomic Responses of Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. Pekinensis) to Salt Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1953. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pavlović I., Petřík I., Tarkowská D., Lepeduš H., Bok V.V., Brkanac S.R., Novak O., Salopek-Sondi B. Correlations between Phytohormones and Drought Tolerance in Selected Brassica Crops: Chinese Cabbage, White Cabbage and Kale. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:2866. doi: 10.3390/ijms19102866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su T., Li P., Wang H., Wang W., Zhao X., Yu Y., Zhang D., Yu S., Zhang F., Wang H. Natural variation in a calreticulin gene causes reduced resistance to Ca2+ deficiency-induced tipburn in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. Pekinensis) Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42:3044–3060. doi: 10.1111/pce.13612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murakami K. Selective fertilization in relation to plant breeding.: I. Chinese cabbage (Brassica pekinensis RUPR.).: 3. Inheritance of self and cross-incompatibility. Jpn. J. Breed. 1965;15:97–109. doi: 10.1270/jsbbs1951.15.97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spizzo G., Fong D., Wurm M., Ensinger C., Obrist P., Hofer C., Mazzoleni G., Gastl G., Went P. EpCAM expression in primary tumour tissues and metastases: An immunohistochemical analysis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011;64:415–420. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2011.090274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang L., Yang Y., Yang F., Liu S., Zhu Z., Lei Z., Guo J. Functions of EpCAM in physiological processes and diseases (Review) Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018;42:1771–1785. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park S.R., Ko K., Lim S., Cha S.Y., Chung H.J., Park S.J., Myung S., Kim M.K. In vitro wound healing: Inhibition activity of insect-derived mAb CO17-1A in human colorectal cancer cell migration. Èntomol. Res. 2020;50:199–204. doi: 10.1111/1748-5967.12425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macdonald J., Henri J., Roy K., Hays E., Bauer M., Veedu R.N., Pouliot N., Shigdar S. EpCAM Immunotherapy versus Specific Targeted Delivery of Drugs. Cancers. 2018;10:19. doi: 10.3390/cancers10010019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Went P.T., Lugli A., Meier S., Bundi M., Mirlacher M., Sauter G., Dirnhofer S. Frequent EpCam Protein Expression in Human Carcinomas. Hum. Pathol. 2004;35:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2003.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Z., Lee K.-J., Shao Y., Lee J.-H., So Y., Choo Y.-K., Oh D.-B., Hwang K.-A., Oh S.H., Han Y.S., et al. Expression of GA733-Fc Fusion Protein as a Vaccine Candidate for Colorectal Cancer in Transgenic Plants. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012;2012:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2012/364240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brodzik R., Spitsin S., Golovkin M., Bandurska K., Portocarrero C., Okulicz M., Steplewski Z., Koprowski H. Plant-derived EpCAM antigen induces protective anti-cancer response. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2007;57:317–323. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0366-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung I.S., Fu Y.-Y., Zhao J., Park J.-H., Choi G.-W., Park K.Y., Lee Y.H. Human colorectal cancer antigen GA733-2-Fc fused to endoplasmic reticulum retention motif KDEL enhances its immunotherapeutic effects. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2018;14:748–S757. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.199445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perrar A., Dissmeyer N., Huesgen P.F. New beginnings and new ends: Methods for large-scale characterization of protein termini and their use in plant biology. J. Exp. Bot. 2019;70:2021–2038. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erz104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schilling S., Stenzel I., Bohlen A., Wermann M., Schulz K., Demuth H.-U., Wasternack C. Isolation and characterization of the glutaminyl cyclases from Solanum tuberosum and Arabidopsis thaliana: Implications for physiological functions. Biol. Chem. 2007;388:145–153. doi: 10.1515/BC.2007.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang C., Gao X., Gong R. Engineering of Fc Fragments with Optimized Physicochemical Properties Implying Improvement of Clinical Potentials for Fc-Based Therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 2018;8:1860. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kang Y.J., Kim D.-S., Myung S.-C., Eko K. Expression of a Human Prostatic Acid Phosphatase (PAP)-IgM Fc Fusion Protein in Plants Using In vitro Tissue Subculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:274. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moussavou G., Lee J.-H., Qiao L., Noh Y.H., Shin Y.K., Lee T.J., Lee S.H., Eko K. Baculovirus titration method based on MOI values for optimizing recombinant protein expression of the anti-cancer vaccine candidate GA733-Fc using Sf9 insect cells. Èntomol. Res. 2018;48:73–79. doi: 10.1111/1748-5967.12291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J.H., Ko K. Production of Recombinant Anti-Cancer Vaccines in Plants. Biomol. Ther. 2017;25:345–353. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2016.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Epark S.-R., Elim C.-Y., Ekim D.-S., Eko K. Optimization of Ammonium Sulfate Concentration for Purification of Colorectal Cancer Vaccine Candidate Recombinant Protein GA733-FcK Isolated from Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:1040. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.01040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim C.-Y., Lee K.J., Oh D.-B., Eko K. Effect of the developmental stage and tissue position on the expression and glycosylation of recombinant glycoprotein GA733-FcK in transgenic plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;5:778. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sørensen V., Rasmussen I.B., Sundvold V., Michaelsen T.E., Sandlie I. Structural requirements for incorporation of J chain into human IgM and IgA. Int. Immunol. 2000;12:19–27. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webster G., Van Dolleweerd C., Guerra T., Stelter S., Hofmann S., Kim M.-Y., Teh A.Y.-H., Diogo G.R., Copland A., Paul M.J., et al. A polymeric immunoglobulin—Antigen fusion protein strategy for enhancing vaccine immunogenicity. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018;16:1983–1996. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Czajkowsky D.M., Hu J., Shao Z., Pleass R.J. Fc-fusion proteins: New developments and future perspectives. EMBO Mol. Med. 2012;4:1015–1028. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakanishi K., Narimatsu S., Ichikawa S., Tobisawa Y., Kurohane K., Niwa Y., Kobayashi H., Imai Y. Production of Hybrid-IgG/IgA Plantibodies with Neutralizing Activity against Shiga Toxin 1. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yui S., Yoshikawa H. Bolting resistant breeding of Chinese cabbage. 1. Flower induction of late bolting variety without chilling treatment. Euphytica. 1991;52:171–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00029393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park B.-J., Liu Z., Kanno A., Kameya T. Genetic improvement of Chinese cabbage for salt and drought tolerance by constitutive expression of a B. napus LEA gene. Plant Sci. 2005;169:553–558. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Niemann J., Kaczmarek J., Książczyk T., Wojciechowski A., Jedryczka M. Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. Pekinensis)—A valuable source of resistance to clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2016;147:181–198. doi: 10.1007/s10658-016-0991-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park S.R., Lee J.-H., Kim K., Kim T.M., Lee S.H., Choo Y.-K., Kim K.S., Ko K. Expression and In Vitro Function of Anti-Breast Cancer Llama-Based Single Domain Antibody VHH Expressed in Tobacco Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:1354. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pyzik M., Sand K.M.K., Hubbard J.J., Andersen J.T., Sandlie I., Blumberg R.S. The Neonatal Fc Receptor (FcRn): A Misnomer? Front. Immunol. 2019;10:1540. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang X.-Y., Wang B., Wen Y.-M. From therapeutic antibodies to immune complex vaccines. NPJ Vaccines. 2019;4:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41541-018-0095-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim D.-S., Kang Y.J., Lee K.J., Qiao L., Ko K., Kim D.H., Myung S.C., Eko K. A Plant-Derived Antigen–Antibody Complex Induces Anti-Cancer Immune Responses by Forming a Large Quaternary Structure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:5603. doi: 10.3390/ijms21165603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woof J.M., Russell M.W. Structure and function relationships in IgA. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:590–597. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar N., Arthur C.P., Ciferri C., Matsumoto M.L. Structure of the secretory immunoglobulin A core. Science. 2020;367:1008–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharp T.H., Boyle A.L., Diebolder C.A., Kros A., Koster A.J., Gros P. Insights into IgM-mediated complement activation based on in situ structures of IgM-C1-C4b. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:11900–11905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901841116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sieg F., Schroder W., Schmitt J.M., Hincha D.K. Purification and Characterization of a Cryoprotective Protein (Cryoprotectin) from the Leaves of Cold-Acclimated Cabbage. Plant Physiol. 1996;11:215–221. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li J., Gao G., Zhang T., Wu X. The putative phytocyanin genes in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L.): Genome-wide identification, classification and expression analysis. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2013;288:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s00438-012-0726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murashige T., Skoog F. A Revised Medium for Rapid Growth and Bio-Assays with Tobacco Tissue Cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lim S. Ph.D. Thesis. The Graduate School Chung-Ang University; Seoul, Korea: Aug 23, 2019. Modification of Protein and Glycan Structures to Enhance Efficacy of Vaccine Against Cancer in Plant Expression System. [Google Scholar]