Abstract

Objectives:

Reducing anastomotic leak rates after rectosigmoid resection and anastomosis is a priority in patients undergoing gynecologic oncology surgery. Therefore, we investigated the implications of performing near-infrared angiography (NIR) via proctoscopy to assess anastomotic perfusion at the time of rectosigmoid resection and anastomosis.

Methods:

We identified all patients who underwent rectosigmoid resection and anastomosis for a gynecologic malignancy between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2018. NIR proctoscopy was assessed via the PINPOINT Endoscopic Imaging System (Stryker).

Results:

A total of 410 patients were identified, among whom NIR was utilized in 133 (32.4%). There were no statistically significant differences in age, race, BMI, type of malignancy, surgery, histology, FIGO stage, hypertension, diabetes, or preoperative chemotherapy between NIR and non-NIR groups. All cases of rectosigmoid resection underwent stapled anastomosis. The anastomotic leak rate was 2/133 (1.5%) in the NIR cohort compared with 13/277 (4.7%) in the non-NIR cohort (p=0.16). Diverting ostomy was performed in 9/133 (6.8%) NIR and 53/277 (19.9%) non-NIR patients (p<0.001). Postoperative abscesses occurred in 8/133 (6.0%) NIR and 44/277 (15.9%) non-NIR patients (p=0.004). The NIR cohort had significantly fewer postoperative interventional procedures (12/133, 9.0% NIR vs. 55/277, 19.9% non-NIR, p=0.006) and significantly fewer 30-day readmissions (14/133, 10.5% NIR vs. 61/277, 22% non-NIR, p=0.004).

Conclusions:

NIR proctoscopy is a safe tool for assessing anastomotic rectal perfusion after rectosigmoid resection and anastomosis, with a low anastomotic leak rate of 1.5%. Its potential usefulness should be evaluated in randomized trials in patients undergoing gynecologic cancer surgery.

Keywords: Near-infrared angiography, proctoscopy, anastomotic leaks, gynecological malignancies, rectosigmoid resection

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative residual disease is a well-established prognostic factor in advanced or recurrent ovarian and uterine cancer.1-3 Intestinal surgery is required in many cases to achieve complete surgical resection of malignant disease. Most frequently, when the distal colon is involved, a rectosigmoid resection with anastomosis is necessary.4

An anastomotic leak after a bowel resection is a serious complication resulting in significant morbidity and mortality of up to 21%, mostly secondary to infectious complications and sepsis.5 Historically, leak rates from colorectal surgery were reportedly as high as 20-30%, but after the adoption of the air-leak test and stapled anastomoses, these rates have improved to 5-15%.5 In the gynecologic literature, anastomotic leaks have been reported to occur in 6% of patients undergoing cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer requiring bowel resection.6,7 Specifically, rectosigmoid resections are associated with the highest rate of anastomotic leaks.6

Risk factors associated with anastomotic leaks include low anastomosis, preoperative radiation, presence of intraoperative adverse events, poor nutrition, incomplete resection rings, active Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, active chemotherapy, or high-dose steroids.8 Additionally, poor oxygenation due to diminished blood supply is increasingly recognized as a risk factor for an anastomotic leak.9-12 Given this concern, methods of assessing the adequacy of bowel perfusion at the time of resection and anastomosis are of utmost importance. Some of these include visible light spectrophotometry and laser Doppler flowmetry.13

Recently, a newer technique has been introduced to assess anastomotic perfusion. This technique involves systemic administration of indocyanine green (ICG) and its visualization within the anastomotic vasculature using near-infrared (NIR) angiography via proctoscopy. This offers the surgeon a real-time opportunity to evaluate the perfusion of the anastomosis. This influences the surgeon’s decision to revise the anastomosis or, in the instance of poor anastomotic perfusion, create a diverting ileostomy. Demonstration of adequate perfusion offers reassurance and can prevent unnecessary diverting ileostomies. NIR has previously been reported as a safe approach, with promising results in identifying at-risk anastomosis, decreasing leakage rates, and improving outcomes in patients undergoing bowel resection.14-18 The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of NIR proctoscopy during rectosigmoid resection and anastomosis in patients undergoing surgery for gynecologic malignancies.

METHODS

This is a single institution retrospective cohort study. After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), we evaluated all patients who underwent rectosigmoid resection for a gynecologic malignancy at MSKCC between January 1st, 2013 and December 31st, 2018. Patients who underwent rectosigmoid resection were divided into two groups: those who had proctoscopic bowel perfusion assessment with NIR following anastomosis (NIR cohort); and those who did not (non-NIR cohort). Proctoscopic bowel perfusion assessment was performed with the use of PINPOINT Endoscopic Imaging System (Stryker) using NIR fluorescent imaging of systemically injected ICG via procotoscopy.

Study Design and Data Collection

All patients undergoing rectosigmoid resection for a gynecologic malignancy during the study time period were identified, using an institutional database. The decision to utilize NIR proctoscopy with intravenous ICG fluorescence was made at the discretion of the attending surgeon. Patient demographics were collected and included age, body mass index (BMI), race, preoperative chemotherapy within 90 days of surgery, history of prior radiotherapy, diagnosis, histology, stage,19 preoperative albumin, and comorbidities including diabetes, hypertension, current steroid use, and history of smoking. Additional intraoperative assessments were collected and included debulking status (primary, interval, secondary/tertiary), operative time, estimated blood loss (EBL), and total intravenous fluid administration. Variables that were collected specific to the assessment of the rectosigmoid anastomosis included splenic flexure mobilization, method of anastomosis, level of anastomosis from anal verge, tension at anastomosis per attending surgeon’s assessment, and performance of airleak test. Postoperative assessment included duration of hospital stay, complications (including pelvic abscess or anastomotic leak), and readmission rate. Anastomotic leak was defined based on imaging demonstrating an area of contrast extravasation at the area of the anastomosis, in the setting of clinical sign consistent with an anastomotic leak such as tachycardia, hypotension, and peritonitis. Separately, postoperative pelvic abscesses requiring interventional radiology drainage and/or antibiotic treatment were also identified and analyzed.

Surgical Protocol

Intraoperatively, all rectosigmoid resections were performed using a stapled end-to-end anastomosis with an EEA™ stapler (Medtronic); oversewing of the staple line was not part of standard technique. A bubble test was performed in all cases. After completion of the rectosigmoid resection, the surgeon performed a proctoscopy using the PINPOINT Endoscopic Fluorescence Imaging System (Stryker). Using the visible or white light guidance, the PINPOINT endoscope was inserted into the anus and advanced to the level of the staple line of the anastomosis. The surgeon obtained visualization of the proximal and distal ends of the rectosigmoid anastomosis with visualization of the entire anastomosis. A bolus of 3.75 to 7.5mg of ICG (dose was surgeon-dependent) was administered intravenously. The surgeon assessed in real time the perfusion of the anastomosis as adequate (no filling defect and homogeneous microperfusion) or inadequate (filling defect with no ICG microperfusion detection) and determined the surgical plan, including no further intervention, revision of the anastomosis, or creation of a diverting ostomy (Figure 1).

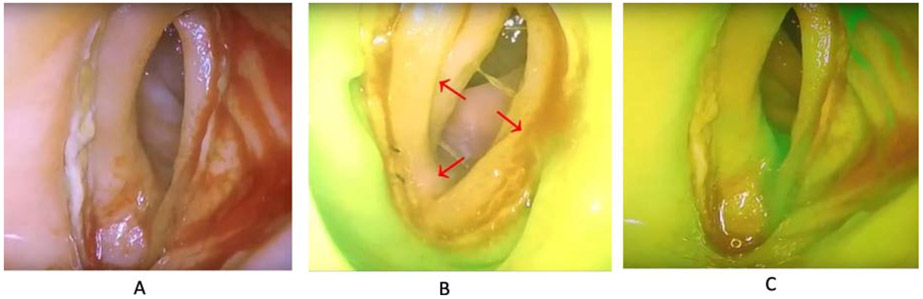

Figure 1:

The use of indocyanine green in assessing anastomotic perfusion of a rectosigmoid resection anastomosis. A) View of rectosigmoid anastomosis via proctoscopy. B) Use of near infrared with ICG demonstrating an area concerning for inadequate perfusion in the proximal portion (red arrows) (C) After anastomotic revision bowel perfusion appreciable along the entire anastomosis. (Courtesy of Allie Straubhar and Dennis Chi) ©MSKCC 2019

Statistical Analysis

The main exposure variable was the use of the NIR proctoscopy camera system. Outcome variables included operative times, EBL, duration of hospital stay, 30-day postoperative complications including anastomotic leaks, pelvic abscesses, and readmission rates. Descriptive statistics were performed for patient characteristics as well as perioperative and postoperative clinical factors. Comparisons between the NIR and non-NIR groups were performed using Fisher’s Exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test for continuous variables.

To examine the impact of NIR on postoperative complications, we combined anastomotic leaks and pelvic abscesses within 30 days post-surgery as the outcome of interest. Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed, assessing the association of NIR with other patient characteristics and perioperative clinical variables. A multivariable logistic regression model was then built based on variables with p-values <0.05 in the univariate setting. The final reported multivariate model was obtained using stepwise model selection methodology. All variables that included only one outcome incidence were excluded from the logistic regression analyses. A two-tailed p-value was reported and considered statistically significant if <0.05. Statistical analysis was conducted on R3.5.2.

RESULTS

A total of 410 patients were included in our analysis. NIR proctoscopy was utilized in 133 (32.4%) of these patients, and was not utilized in 277 (67.6%) patients. Patient characteristics and distribution between NIR and non-NIR cohorts are listed in Table 1. Clinical characteristics were evenly distributed between cohorts (except for smoking history, which was observed more frequently in the NIR cohort compared with the non-NIR cohort (17.3 vs. 9.8%, p = 0.04) and pre-operative albumin which was more elevated (median 4.2 vs. 4.1g/dL, range 2.9–5 vs. 2.4–5; p=0.012).

Table 1:

Clinical characteristics of the study sample (N=410)

| Characteristic | NIR N=133 |

Non-NIR N=277 |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age, years | 62 (22 – 84) | 61 (22 – 85) | 0.373 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.2 (18.5 – 49.4) | 25.4 (17 – 47.2) | 0.2 |

| Race | 0.713 | ||

| White | 103 (79.8) | 226 (83.1) | |

| AA | 10 (7.8) | 19 (7.0) | |

| Asian/Other | 16 (12.4) | 27 (9.9) | |

| Diagnosis* | 0.743 | ||

| Ovarian/FT/PP | 118 (89.4) | 243 (87.7) | |

| Uterine | 14 (10.6) | 34 (12.3) | |

| Histology | 0.807 | ||

| HGSOC | 99 (74.4) | 210 (75.8) | |

| Non-HGSOC | 34 (25.6) | 67 (24.2) | |

| FIGO staging | 0.291 | ||

| I/II | 12 (9.4) | 18 (6.5) | |

| III | 67 (52.8) | 167 (60.3) | |

| IV | 48 (37.8) | 92 (33.3) | |

| Preoperative Chemotherapy | 0.183 | ||

| No | 94 (70.7) | 213 (76.9) | |

| Yes | 39 (29.3) | 64 (23.1) | |

| Preoperative Radiation | 0.536 | ||

| No | 128 (96.2) | 270 (97.5) | |

| Yes | 5 (3.8) | 7 (2.5) | |

| Diabetes | |||

| No | 120 (90.2) | 258 (93.1) | 0.328 |

| Yes | 13 (9.8) | 19 (6.9) | |

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 83 (62.4%) | 186 (67.1) | 0.375 |

| Yes | 50 (37.6) | 91 (32.9) | |

| Steroid Use | |||

| No | 125 (94) | 266 (96) | 0.452 |

| Yes | 8 (6) | 11 (4) | |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 110 (82.7) | 249 (90.2) | 0.036 |

| Yes | 23 (17.3) | 27 (9.8) | |

| Preoperative Albumin, g/dL | 4.2 (2.9 – 5) | 4.1 (2.4 – 5) | 0.012 |

| Debulking Surgery | |||

| Primary | 68 (51.1) | 176 (63.5) | 0.053 |

| Interval | 32 (24.1) | 47 (17) | |

| Secondary/Tertiary | 33 (24.8) | 54 (19.5) |

Values are presented as numbers (%) or median (range)

FT, fallopian tube; PP, primary peritoneal; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecologic Oncology

one case of synchronous ovarian and uterine carcinoma

Intraoperative measures and operative characteristics of rectosigmoid anastomosis, with or without the use of NIR, are listed in Table 2. The median procedure times did not differ between the NIR and non-NIR cohorts (458 vs. 471 minutes, range 250–1011 vs. 213–1296; p=0.619). There was no significant difference between the distribution of high-risk (<10 cm) versus low-risk (≥10 cm) anastomoses based on the distance from the anal verge to the anastomosis (p=0.206). EBL and use of intraoperative intravenous fluid (IVF) volume were significantly higher in the non-NIR group. Significantly fewer patients underwent diverting ostomies in the NIR cohort (9/133, 6.8%) compared with the non-NIR cohort (53/277, 19.9%; p<0.001).

Table 2:

Intraoperative measures and operative characteristics of LAR anastomosis with or without the use of NIR

| NIR N=133 |

Non-NIR N=277 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative Measures | |||

| Total operative time, minutes | 458 (250 – 1011) | 471 (213 – 1296) | 0.619 |

| Estimated blood loss, milliliters | 680 (25 – 5100) | 800 (100 – 6500) | 0.042 |

| Total intravenous fluids* | 3500 (1000 – 15000) | 4200 (500 – 13000) | <0.001 |

| Operative Characteristics | |||

| Splenic Flexure Mobilization# | 128 (96.2) | 251 (91.9) | 0.137 |

| Surgical technique | |||

| Stapled^ | 133 (100) | 271 (97.8) | 1 |

| Level of anastomosis** | |||

| <10cm | 35 (26.5) | 87 (33) | 0.206 |

| ≥ 10cm | 97 (73.5) | 177 (67) | |

| No tension at anastomosis# | 132 (99.2) | 267 (96.4) | 1 |

| Air leak test performed# | 132 (99.2) | 265 (95.7) | 1 |

| Diverting Ostomy | 9 (6.8) | 55 (19.9) | <0.001 |

Values are presented as numbers (%) or median (range); unknown cases excluded from percent reported LAR, low anterior resection; NIR, near-infrared

crystalloids only, milliliters

6 cases with unreported data in the non-NIR cohort

as measured from anal verge, 14 cases with unreported data

all remaining cases with unknown variable of interest

Postoperative data are listed in Table 3. The anastomotic leak rate was 2/133 (1.5%) in the NIR cohort compared with 13/277 (4.7%) in the non-NIR cohort (p=0.159). Postoperative abscesses occurred in 8/133 (6.0%) NIR patients and 44/277 (15.9%) non-NIR patients (p=0.004). The NIR cohort had significantly fewer postoperative interventional procedures (12/133, 9.0% NIR vs. 55/277, 19.9% non-NIR; p=0.006) and significantly fewer 30-day readmissions (14/133, 10.5% NIR vs. 61/277, 22% non-NIR; p=0.004). Length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in the NIR cohort (p=0.016).

Table 3:

Postoperative data on the use of NIR in evaluation of LAR anastomoses

| All Cases N= 410 |

NIR N=133 |

Non-NIR N=277 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital stay (days) | 8 (2-36) | 7 (3-22) | 8 (2-36) | 0.016 |

| Complications | ||||

| Post-op abscess | 52 (12.7) | 8 (6) | 44 (15.9) | 0.004 |

| Anastomotic leak | 15 (3.7) | 2 (1.5) | 13 (4.7) | 0.159 |

| Post-operative procedure | 67 (16.3) | 12 (9.0) | 55 (19.9) | 0.006 |

| Readmission Rate* | 75 (18.3) | 14 (10.5) | 61 (22) | 0.004 |

Values are presented as numbers (%) or median (range)

NIR, near infrared; LAR, low anterior anastomosis

within 30 days of surgery

On univariate analysis (Table 4) FIGO stage, EBL, total IVF, diverting ostomy and NIR proctoscopy were significantly associated with anastomotic leak or postoperative abscess. Specifically, the use of NIR proctoscopy was associated with a 61% reduction in the odds of anastomotic leak and postoperative abscess (p=0.009). The multivariate model demonstrated that FIGO stage, total IVF, and the use of NIR were independently associated with anastomotic leak and postoperative abscess (Table 5). After adjusting for FIGO stage and total IVF, the use of NIR proctoscopy was associated with a 60% reduction in odds of anastomotic leak and postoperative abscess (p=0.020).

Table 4:

Univariate logistic regression analysis of demographics and surgical variables associated with incidence of anastomotic leak and postoperative abscesses

| Variables | Levels | OR | 95%CI Lower Bound |

95%CI Upper Bound |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at surgery | as 1 yr increase | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.03 | 0.91 |

| Body mass index at surgery | as 1 kg/m2 increase | 1.02 | 0.97 | 1.07 | 0.42 |

| Race | 0.52 | ||||

| AA vs white | 1.69 | 0.60 | 4.15 | ||

| Asia/other vs white | 1.26 | 0.49 | 2.86 | ||

| Diagnosis | Uterine vs Ovarian/FT/PP | 0.85 | 0.31 | 1.96 | 0.72 |

| Histology | non-HGSOC vs HGSOC | 1.08 | 0.56 | 2.00 | 0.81 |

| FIGO staging | 0.038 | ||||

| III vs I/II | 0.50 | 0.21 | 1.27 | ||

| IV vs I/II | 0.28 | 0.11 | 0.78 | ||

| Preoperative Chemotherapy | Yes vs No | 0.75 | 0.36 | 1.43 | 0.40 |

| Diabetes | Yes vs No | 0.86 | 0.25 | 2.29 | 0.36 |

| Hypertension | Yes vs No | 1.30 | 0.73 | 2.29 | 0.78 |

| Steroid Use | Yes vs No | 1.66 | 0.46 | 4.79 | 0.38 |

| Smoking | Yes vs No | 1.66 | 0.46 | 4.79 | 0.38 |

| Preoperative Albumin | as 1g/dL increase | 0.63 | 0.33 | 1.25 | 0.18 |

| Debulking Surgery | 0.59 | ||||

| Interval vs Primary | 0.70 | 0.30 | 1.46 | ||

| Secondary/Tertiary vs Primary | 0.78 | 0.37 | 1.57 | ||

| Total operative time | as 1-minute increase | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.06 |

| Estimated blood loss | as 200ml increase | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.12 | 0.036 |

| Total intravenous fluids | as 1000ml increase | 1.26 | 1.12 | 1.41 | <0.001 |

| Splenic Flexure Mobilization | Yes vs No | 1.30 | 0.43 | 5.61 | 0.68 |

| Level of anastomosis | ≥ 10cm vs <10cm | 0.82 | 0.46 | 1.50 | 0.51 |

| Diverting Ostomy | Yes vs No | 2.41 | 1.23 | 4.57 | 0.008 |

| NIR technique | Yes vs No | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.76 | 0.009 |

FT, fallopian tube; PP, primary peritoneal; HGSOC, high-grade serous ovarian cancer; NIR, near infrared

Table 5:

Multivariate logistic model for anastomotic leak and postoperative abscesses after model selection

| N = 402(event#=57) | OR | 95% CI | p- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIGO Stage | 0.016 | ||

| III vs I/II | 0.44 | 0.17, 1.17 | |

| IV vs I/II | 0.22 | 0.08, 0.65 | |

| IVF (as 1000ml increase) | 1.27 | 1.13, 1.44 | <0.001 |

| NIR technique (yes vs no) | 0.40 | 0.17, 0.83 | 0.020 |

Adjusted for FIGO staging, estimated blood loss, total intravenous fluids, diverting ostomy, and use of NIR technique

IVF, intravenous fluids; NIR, near infrared

DISCUSSION

In patients undergoing surgical debulking for a gynecological malignancy requiring a rectosigmoid resection, our data indicates that the use of NIR proctoscopy to assess anastomotic rectal perfusion is associated with improved postoperative outcomes when performed in addition to the traditional airleak test and surgeon visual assessment. The surgeon’s visual assessment, which includes assessment of active bleeding from the resection margin, palpable pulsation in the mesentery, and lack of discoloration, is critical in deciding to proceed with an anastomosis.17 Our findings are consistent with previously published safety data in the colorectal literature evaluating the NIR platform in assessment of intestinal anastomoses.17,18,20 Specifically, our findings indicate an improvement in anastomotic leak and infection rates among those patients undergoing rectosigmoid resection with the use of NIR, as it provides an opportunity to identify poor perfusion, leading to the reinforcement or revision of the anastomosis. Importantly, the data suggests there is further benefit to the patient when the technique is employed, as it appears to result in fewer unnecessary ileostomy creations, likely secondary to surgeon reassurance.

Recent studies have described a significant decrease in leak rates with the use of ICG imaging to assess anastomotic perfusion in rectal cancer surgery.21 A recent meta-analysis reported a significant decrease in leak rates from 6.1% to 1.1% when ICG was used to evaluate anastomotic perfusion. Our data demonstrated a similar leak rate of 1.5% in the NIR cohort compared with 4.7% in the non-NIR cohort. This was not statistically significant. However, use of diverting ostomies, postoperative abscesses, re-operations, readmsissions, and length of hospital stay were significantly lower in the NIR cohort.

This retrospective study has several limitations. The use of NIR proctoscopy was introduced in early 2013 at our institution and was used infrequently in the beginning, with a steady increase over time. Its use was at the discretion of the surgeon, and initially was performed by few surgeons before it was more widely adopted. The surgeon- and time-bias may account for differences in surgical outcomes. During the study period several service-wide changes were implemented, which could have had an impact on surgical outcomes. Specifically, the Surgical Site Reduction bundle (SSI) and Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) bundle were introduced, resulting in lower total IVF, early postoperative oral nutrition, and preoperative oral antibiotics over time, all of which could have impacted anastomotic leak rate, rate of abscess, and other complications resulting in readmissions.22 Similarly, preoperative bowel preparation was at the discretion of the attending surgeon, and the impact of bowel preparation on proctoscopy visualization and postoperative outcomes is not evaluated in this study. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with caution.

Nevertheless, this retrospective analysis of NIR proctoscopy demonstrates a significant reduction in combined anastomotic leak and postoperative abscess, resulting in fewer readmissions and shorter length of hospital stay, without increasing operative time. The appropriate next step is to perform a multi-institutional randomized trial to confirm whether or not NIR proctoscopy can reduce the rate of anastomotic leak, postoperative abscess requiring intervention, and readmission. A multi-institutional randomized controlled trial is planned to further evaluate the true implications of the use of NIR proctoscopy in gynecologic cancer surgery.

Highlights.

There is a 1.5% leak rate when NIR technology is used to evaluate anastomotic perfusion after a rectosigmoid resection.

Use of NIR proctoscopy to assess anastomotic perfusion is associated with improved postoperative outcomes.

NIR proctoscopy offers an intraoperative tool to aid in surgical decision-making regarding the integrity of an anastomosis.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

Disclosures:

Dr. Iasonos reports personal fees from Mylan, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Abu-Rustum reports grants from Stryker/Novadaq, grants from Olympus, grants from GRAIL, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Leitao is a consultant for Intuitive Surgical Inc., outside the submitted work.

Dr. Chi reports personal fees from Bovie Medical Co., personal fees from Verthermia Inc. (now Apyx Medical Corp.), personal fees from C Surgeries, other from Intuitive Surgical, Inc., other from TransEnterix, Inc., personal fees from Biom 'Up, outside the submitted work.

Dr. Long Roche reports other* from Intuitive Surgical Inc., outside the submitted work. (*Airfare to a survivorship conference, where she spoke).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ. Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(5):1248–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar S, Nath R, Lane G, Mehra G, Begum S, Sayasneh A. Advanced stage (IIIC/IV) endometrial cancer: Role of cytoreduction and determinants of survival. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;234:26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlin JN, Puri I, Bristow RE. Cytoreductive surgery for advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118(1):14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peiretti M, Bristow RE, Zapardiel I, et al. Rectosigmoid resection at the time of primary cytoreduction for advanced ovarian cancer. A multi-center analysis of surgical and oncological outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;126(2):220–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumetti J, Chaudhry V, Cintron JR, et al. Management of anastomotic leak: lessons learned from a large colon and rectal surgery training program. World J Surg. 2014;38(4):985–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimm C, Harter P, Alesina PF, et al. The impact of type and number of bowel resections on anastomotic leakage risk in advanced ovarian cancer surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;146(3):498–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseng JH, Suidan RS, Zivanovic O, et al. Diverting ileostomy during primary debulking surgery for ovarian cancer: Associated factors and postoperative outcomes. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;142(2):217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutegard M, Rutegard J. Anastomotic leakage in rectal cancer surgery: The role of blood perfusion. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;7(11):289–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle NH, Manifold D, Jordan MH, Mason RC. Intraoperative assessment of colonic perfusion using scanning laser Doppler flowmetry during colonic resection. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2000;191(5):504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vignali A, Gianotti L, Braga M, Radaelli G, Malvezzi L, Di Carlo V. Altered microperfusion at the rectal stump is predictive for rectal anastomotic leak. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43(1):76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheridan WG, Lowndes RH, Young HL. Tissue Oxygen-Tension as a Predictor of Colonic Anastomotic Healing. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30(11):867–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kologlu M, Yorganci K, Renda N, Sayek I. Effect of local and remote ischemia-reperfusion injury on healing of colonic anastomoses. Surgery. 2000;128(1):99–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Urbanavicius L, Pattyn P, de Putte DV, Venskutonis D. How to assess intestinal viability during surgery: A review of techniques. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;3(5):59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ris F, Hompes R, Cunningham C, et al. Near-infrared (NIR) perfusion angiography in minimally invasive colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(7):2221–2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong G, Croft J, Corrigan N, et al. IntAct: intra-operative fluorescence angiography to prevent anastomotic leak in rectal cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis. 2018;20(8):O226–O234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jafari MD, Wexner SD, Martz JE, et al. Perfusion assessment in laparoscopic left-sided/anterior resection (PILLAR II): a multi-institutional study. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220(1):82–92 e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kudszus S, Roesel C, Schachtrupp A, Hoer JJ. Intraoperative laser fluorescence angiography in colorectal surgery: a noninvasive analysis to reduce the rate of anastomotic leakage. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2010;395(8):1025–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jafari MD, Lee KH, Halabi WJ, et al. The use of indocyanine green fluorescence to assess anastomotic perfusion during robotic assisted laparoscopic rectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(8):3003–3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.network Ncc. 2019; https://www.nccn.org/. Accessed October 10, 2019.

- 20.Watanabe J, Ishibe A, Suwa Y, et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence imaging to reduce the risk of anastomotic leakage in laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanco-Colino R, Espin-Basany E. Intraoperative use of ICG fluorescence imaging to reduce the risk of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2018;22(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schiavone MB, Moukarzel L, Leong K, et al. Surgical site infection reduction bundle in patients with gynecologic cancer undergoing colon surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;147(1):115–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]