Abstract

Collectively, vast quantities of brain imaging data exist across hospitals and research institutions, providing valuable resources to study brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, in practice, putting all these distributed datasets into a centralized platform is infeasible due to patient privacy concerns, data restrictions and legal regulations. In this study, we propose a novel federated feature selection framework that can analyze the data at each individual institution without data-sharing or accessing private patient information. In this framework, we first propose a federated group lasso optimization method based on block coordinate descent. We employ stability selection to determine statistically significant features, by solving the group lasso problem with a sequence of regularization parameters. To accelerate the stability selection, we further propose a federated screening rule, which can identify and exclude the irrelevant features before solving the group lasso. Here, we use this framework for patch based feature selection on hippocampal morphometry. Shape is characterized through two different kinds of local measures, the radial distance and the surface area determined via tensor-based morphometry (TBM). The method is tested on 1,127 T1-weighted brain magnetic resonance images (MRI) of AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and elderly control subjects, randomly assigned to five independent hypothetical institutions for testing purpose. We examine the association of MRI-based anatomical measures with general cognitive assessment and amyloid burden to identify the morphometry changes related to AD deterioration and plaque accumulation. Finally, we visualize the significance of the association on the hippocampal surfaces. Our experimental results successfully demonstrate the efficiency and effectiveness of our method.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s Disease, Federated Learning, Feature Selection, Group Lasso, Surface-Based Morphometry, Amyloid Burden

1. INTRODUCTION

Unprecedentedly large numbers of brain magnetic resonance images (MRI) now exist across hospitals and research institutions. Simultaneously, the fast development of software and hardware makes it technically possible to unearth invaluable information from these combined datasets about the underpinnings of brain disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, patient privacy concerns, data restrictions and legal complexities have all been major obstacles for researchers to obtain or share these images. To remedy this problem, large-scale collaborative networks were built, such as the ENIGMA Consortium,1 which have adopted secure meta-analyses to study the data from hundreds of institutions worldwide without sharing patients’ scans and protected information.

Most of ENIGMA’s meta-analytic studies focus on univariate measures derived from the original images, which may fail to consider relationships between neighboring voxels. Recently, federated learning models like decentralized independent component analysis2 and sparse regression3 have made solid progress with leveraging multivariate image features for statistical inferences. However, in brain imaging research, it is more interesting to find significant explanatory factors that can predict/relate to clinical outcomes or cognitive performance, such as finding anatomically abnormal regions in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) patients’ brains. Therefore, using patch-based surface morphometry features from T1-weighted brain MRI images of AD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and healthy elderly control subjects, we propose a novel federated feature selection system based on group lasso regression and use it to assess morphological changes associated with AD deterioration in cognition (assessed through a general cognition test, the Mini-Mental State Examination or MMSE) and beta-amyloid plaque accumulation (based on uniform PET amyloid Centloid quantification). Our work generalizes and enriches federated learning research by explicitly selecting (and visualizing) key features. By increasing access to information from large imaging datasets, our method may uncover new important features to be used as imaging biomarkers of MCI and AD.

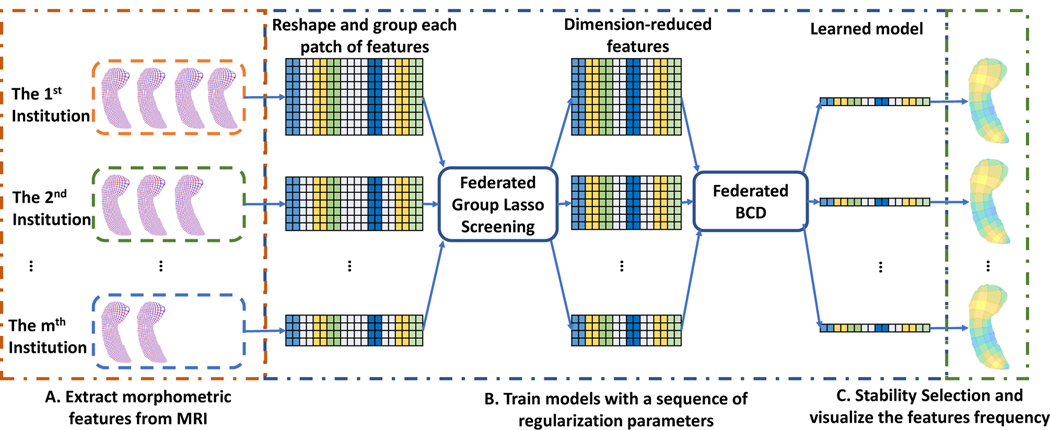

Our proposed framework is shown as Fig. 1. Briefly, based on its own T1-weighted magnetic resonance images (MRI), each institution locally computes two morphometric features, the radial distance (RD)4,5 from a central axis and surface tensor-based morphometry (TBM) 6–9 - characterizing the thickness and surface area of the hippocampus around a vertex, respectively. Secondly, it uniformly selects patches on each hippocampal surface, groups the features in each patch and finally reshapes the features of each individual into a vector. With these grouped features and the responses (MMSE or Centiloid), the framework solves the group lasso problem with a descent sequence of regularization parameters in a distributed manner. Beforehand, we employ a novel federated group lasso screening method, which we call the federated dual polytope projection for group lasso (FDPP_GL), to identify and remove the groups of features for which the corresponding solution vector is zero. With the dimension-reduced features, we can efficiently solve the optimization problem using a proposed federated block coordinate descent (FBCD). Then, the final solution vectors are assigned to each institution and they perform the stability selection10 by counting how often each entry in the solution vector is zero on each vertex. The frequency represents how significantly the vertex is related to the response. Finally, we visualize the frequency on the hippocampal surface.

Figure 1.

Illustration of our federated feature selection framework. Each institution maintains its own imaging data and locally calculates RD and TBM. After patching and reformatting the features, we first employ the federated group lasso screening rule to identify and remove irrelevant features and we then run the federated block coordinate descent. Finally, each institution obtains the same learned models and performs stability selection to rank the association between the surface changes and MMSE or Centiloid. This association will be visualized on the hippocampal surface to study brain disorders affecting its anatomy.

The main contributions of this work are as follows. Firstly, our proposed federated feature selection framework achieved superior performance in efficiency compared with similar feature selection methods with group lasso, such as the state-of-the-art distributed solver with the alternating direction method of multipliers algorithm (ADMM).11 Secondly, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first feature selection model to study hippocampal morphometric changes with amyloid plaque accumulation in AD. Finally, the visualization of these abnormalities will contribute to novel exploration of brain disorders. Importantly, beyond brain MRI, our framework can also be applied to any other kinds of medical data for feature selection.

2. DATA DESCRIPTION

The data used in this paper were downloaded from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) project database. From ADNI, we collected 1,127 T1-weighted MR images from 173 AD patients, 516 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) patients and 438 asymptomatic normally aging seniors (CTL). Besides, for each MRI scan, we also collected its corresponding MMSE and Centiloid scale12 results. The Centiloid scale is a comparison parameter obtained from amyloid PET imaging data as a measure of the amyloid burden of brains. The mean amyloid burden measurement for a control group (no amyloid pathology) is represented as 0 on the Centiloid scale, while that of an AD group is 100.

3. METHODS

3.1. Federated Block Coordinate Descent for Group Lasso

Group lasso13 is a very popular technique for group-wise feature selection for high dimensional data. A group-lasso linear regression has the following optimizing problem:

| (1) |

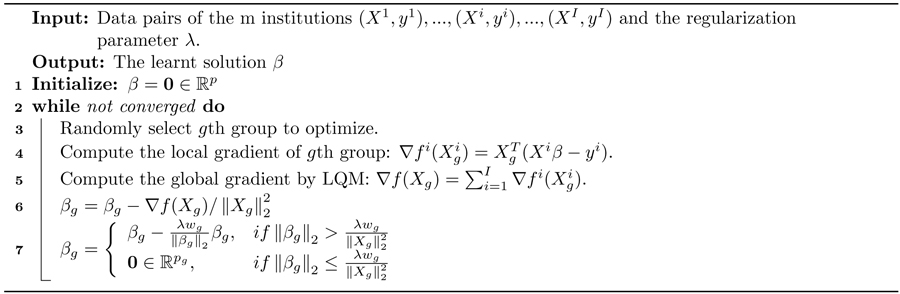

Algorithm 1:

Federated Block Coordinate Descent

|

where is the feature matrix and y denotes the N dimensional response vector. Group lasso divides the original feature matrix into G different groups, where Xg represents the features in gth group and wg is the weight for this group. After solving the group lasso problem, we get the G solution vectors, β1, β2,...,βG. The dimension of each group, pg, can be arbitrary and the whole solution vector β is . Additionally, λ is a positive regularization parameter to control the sparsity of the solution vector and wg is the weight for gth group of features.

There are many optimization methods to solve the group lasso problem; block coordinate descent (BCD)14 is one of the most efficient. Instead of updating all the variables at the same time, BCD only updates one or several blocks of variables at each epoch. Therefore, for the group lasso problem, it can optimize one group of variables while keeping the other ones fixed. Based on this idea, we propose a federated block coordinate descent to solve our problem.

Li et al. proposed an optimization model, the local query model (LQM), which preserves the data privacy of each institution.15 Let us assume that there are I institutions, and that each of them owns a private data set . We can reformulate the problem 1 as minβ , where is the least square loss of the ith institution. We then have the global gradient . Each of the local institutions calculates its own gradient locally and uploads it to the master server. The latter is used only to determine the gradient with respect to X, by adding all together. It then assigns the global update gradient back to all the local institutions to compute β. We didn’t consider the missing data conditions here and techniques like16,17 can deal with these conditions. Besides, many privacy-preserving techniques can be used in the gradient transmission. We leave these issues for a future study. Our proposed federated block coordinate descent is outlined in Alg. 1.

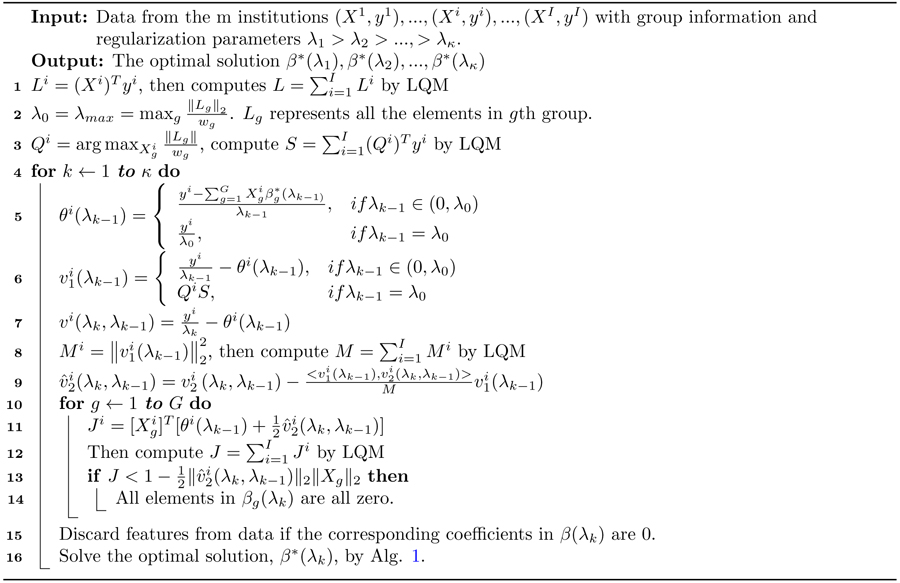

3.2. Federated Screening Rule for Group Lasso

Finding the optimal value for the regularization parameter λ is a common problem in lasso techniques. The most frequently-used methods, such as cross-validation, solve it by trying a sequence of regularization parameters, λ1 > ... > λκ, which can be very time-consuming. Instead, the enhanced dual polytope projection rule (EDPP)18 achieved a 200x speedup on the cross-validation in real world applications, by using the information derived from the solution of its previous regularization parameter. For the group lasso problem, the gth group of features Xg can be discarded if it satisfies the screening rule, , where and Jg and Lg are the elements of J and L defined in Alg. 2. The screening rule is based on the uniqueness and non-expansiveness of the optimal dual solution, because the feasible set in the dual space is a convex and closed polytope. More information on EDPP can be found at GitHub: http://dpc-screening.github.io/glasso.html.

Following the strong rule, we further propose a federated screening rule for group lasso, named federated dual polytope projection for group lasso (FDPP_GL), to rapidly locate the inactive features in a distributed manner while preserving data privacy at each institution. We summarize the method in Alg. 2. In the algorithm, we estimate the maximum regularization parameter, λmax. The input sequence of parameters, λ1...λκ, should be no greater than λmax. Based on the solutions with the sequence of regularization parameters, we can then perform stability selection10 to select the significant features.

3.3. Feature Extraction and Selection

In this work, we extracted two surface morphometric features from the T1-weighted MR images, including radial distance (RD)4,5 and surface tensor-based morphometry (TBM),6–9 which characterize vertex-wise changes in hippocampal thickness and regional surface area, respectively. After normalizing the MRI scans to the MNI template space, the hippocampal segmentation was conducted by FIRST with default settings in FSL.19 For each pair of hippocampal surfaces, we then extracted the vertex-wise morphometric features following the same procedures as in Shi et al.20 Using the conformal parameterization in Wang et al.,21 each surface was mapped to a rectangle, which consists of a uniform vertex matrix (100 × 150). In other words, each surface had 100 × 150 well-aligned vertices, and each vertex contained two different kinds of features, RD and TBM. RD refers to the distance from a medial axis to a vertex on the surface and TBM examines the Jacobian matrix J of the deformation map that registers the surface to a template surface. For TBM, was computed at each vertex, and this value reflects how the surface area changed around the vertex (expansion or atrophy). In this way, we extracted 15,000 RD and 15,000 TBM for each hippocampal surface. Finally, we used the heat kernel smoothing algorithm22,23 to refine the surface features.

On each 100 × 150 surface, we uniformly selected 2,500 patches, of size 2 × 3, and the same kind of features in one patch were considered as a group. We selected this patch size of 2 × 3 not only because it can increase the robustness of the feature selection model, but also because it will not have an obvious influence on the visualization. Since each MRI scan has two hippocampal surfaces, the feature dimension for each individual is p = (15000 + 15000) × 2. We then carried out the above-mentioned group lasso method to select features. Given a decreasing sequence of regularization parameters, λ1,...,λκ, we learned a set of corresponding models, β(λ1),...,β(λκ). We then performed the stability selection by counting the frequency of nonzero entries in the learned models and visualize the frequency on the surface. We will discuss the detail of visualization in the next section.

4. EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

In this section, we first assess the efficiency and accuracy of our proposed framework, and secondly, we introduce a visualization of the significant features. We simulated the distributed condition on a cluster with tens of conventional x86 nodes, of which each contains two Intel Xeon E5–2680 v4 CPUs running at 2.40GHz. And all the algorithms were developed with C for fair comparison.

4.1. Running Time Comparison

In this experiment, we were trying to demonstrate that our proposed framework, FDPP_GL+FBCD, has superior efficiency compared with the state-of-the-art distributed ADMM (DADMM).11 We also tested the running of

Algorithm 2:

Federated Dual Polytope Projection for Group Lasso

|

FBCD without using the screening rule.

Firstly, we randomly assigned the 1,127 subjects to five institutions. Every institution had almost the same number of subjects and one computation node. We uniformly selected 100 regularization parameters from 1.0 to 0.1 and ran all three methods with the same setup. To compare them further, we randomly down-sampled or up-sampled the dimension of the features, as shown in Fig. 2. Although FBCD had similar performance as DADMM, our proposed framework, FDPP_GL+FBCD, achieved a speedup up to 89 fold.

Figure 2.

Comparison of running time. For the features with different dimensions, our framework compared with DADMM achieved a speedup of 62 fold, 80 fold, 86 fold and 89 fold.

4.2. Prediction Accuracy Comparison

If there is no loss during communication, our proposed framework will have the same performance on the different multi-institution conditions as well as the data-centralized condition. To evaluate accuracy, we performed 5-fold cross-validation on the ADNI data set under three conditions, including a data-centralized condition, three institutions, and five institutions. For each training data set, we randomly assigned the subjects to three institutions, five institutions or a single institution. Besides, we also compared the performance of FBCD and DADMM under the five-institution condition. We performed cross-validation for 10 times with a sequence of regularization parameters, 1, 0.5 and 0.1, and with all the other experimental setups being the same as last experiment. The mean and standard derivation of the root mean square error of the train set and test set are shown in Tab. 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of RMSE.

| λ | FDPP_GL(1) | FDPP_GL(3) | FDPP_GL(5) | FBCD(5) | DADMM(5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | 1.0 | 2.796 ± 0.000 | 2.796 ± 0.000 | 2.796 ± 0.000 | 2.796 ± 0.000 | 2.796 ± 0.000 |

| 0.5 | 2.700 ± 0.007 | 2.700 ± 0.007 | 2.700 ± 0.007 | 2.700 ± 0.007 | 2.700 ± 0.008 | |

| 0.1 | 2.429 ± 0.009 | 2.429 ± 0.007 | 2.429 ± 0.009 | 2.429 ± 0.009 | 2.438 ± 0.008 | |

| Test | 1.0 | 2.786 ± 0.006 | 2.786 ± 0.006 | 2.786 ± 0.006 | 2.786 ± 0.006 | 2.786 ± 0.006 |

| 0.5 | 2.709 ± 0.008 | 2.709 ± 0.007 | 2.709 ± 0.008 | 2.709 ± 0.008 | 2.711 ± 0.007 | |

| 0.1 | 2.594 ± 0.010 | 2.594 ± 0.011 | 2.594 ± 0.010 | 2.595 ± 0.010 | 2.604 ± 0.013 |

4.3. Selected Feature Analysis

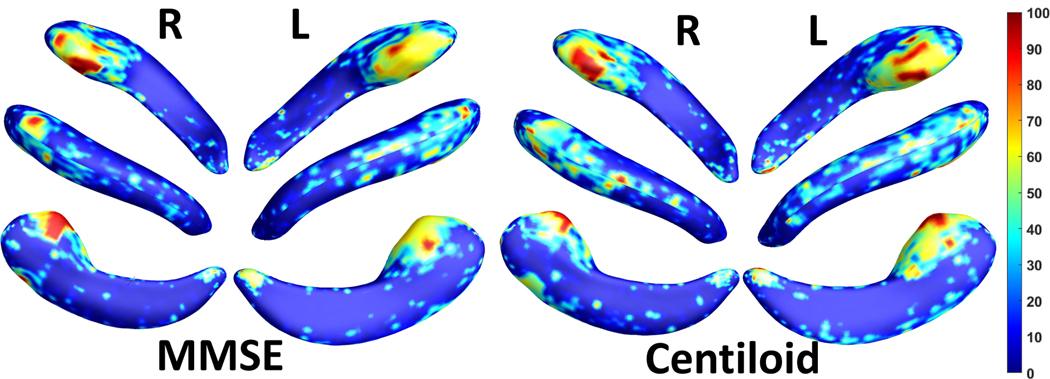

We employed stability selection with our FDPP_GL+FBCD to calculate the significance of the vertices on the hippocampal surfaces to MMSE or Centiloid. To select the most significant features, we uniformly generated 100 regularization parameters between 0.01 to 0.001. The two features, RD and TBM, were separately normalized with Z-score. After training the model, we got 100 solution vectors. The dimension of each vector is 60,000, since each of the left and right hippocampal surfaces contains 15,000 vertices, and each vertex has two features. Then, we performed stability selection by counting the nonzero entries for RD and TBM on the same vertex. The counted frequency on each vertex was normalized to 1 to 100, and then mapped to a color bar, as shown in Fig. 3. For better visualization, we smoothed the values on each surface with a 2 × 3 averaging filter. The warmer color areas have a higher frequency value. In other words, these areas have more significant associations with MMSE or Centiloid. Results are shown in Fig. 3. The morphometry changes mainly happen at the hippocampal subregions, the subiculum and CA1, consistent with results of some previous work.20,24–26

Figure 3.

Visualization of significant areas. The changes of the surface with warmer color have closer associations with MMSE or Centiloid. The changes are concentrated at two hippocampal sub-regions, the subiculum and CA1, which is consistent with results from other works such as.20,24,25

5. CONCLUSION

In this work, we proposed an efficient federated feature selection framework and obtained superior performance in efficiency and effectiveness. The visualization of the detected morphometry changes will contribute to the exploration of brain disease. In the future, we will extend our framework to the study of brain disorders using whole brain morphometry features.

Table 1.

Demographic information of subjects in this study

| Cohort | # | Gender(M/F) | Age | MMSE | Centiloid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTL | 438 | 200/238 | 74.5 ± 6.5 | 29.0 ± 1.2 | 24.4 ± 33.3 |

| MCI | 516 | 291/225 | 72.6 ± 7.8 | 28.0 ± 1.7 | 42.0 ± 40.7 |

| AD | 173 | 98/75 | 75.0 ± 7.8 | 22.7 ± 2.9 | 72.0 ± 40.2 |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported in part by NIH grants (R21AG065942, RF1AG051710, R01EB025032, U54EB020403, R01AG031581 and P30AG19610) and by the Arizona Alzheimer Consortium.

REFERENCES

- [1].Thompson PM, Stein JL, Medland SE, Hibar DP, Vasquez AA, Renteria ME, Toro R, Jahanshad N, Schumann G, Franke B, et al. , “The enigma consortium: large-scale collaborative analyses of neuroimaging and genetic data,” Brain imaging and behavior 8(2), 153–182 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Baker BT, Silva RF, Calhoun VD, Sarwate AD, and Plis SM, “Large scale collaboration with autonomy: Decentralized data ica,” in [2015 IEEE 25th international workshop on machine learning for signal processing (MLSP)], 1–6, IEEE; (2015). [Google Scholar]

- [3].Plis SM, Sarwate AD, Wood D, Dieringer C, Landis D, Reed C, Panta SR, Turner JA, Shoemaker JM, Carter KW, et al. , “Coinstac: a privacy enabled model and prototype for leveraging and processing decentralized brain imaging data,” Frontiers in neuroscience 10, 365 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pizer SM, Fritsch DS, Yushkevich PA, Johnson VE, and Chaney EL, “Segmentation, registration, and measurement of shape variation via image object shape,” IEEE transactions on medical imaging 18(10), 851–865 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, De Zubicaray GI, Janke AL, Rose SE, Semple J, Hong MS, Herman DH, Gravano D, Doddrell DM, et al. , “Mapping hippocampal and ventricular change in alzheimer disease,” Neuroimage 22(4), 1754–1766 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Davatzikos C, “Spatial normalization of 3d brain images using deformable models,” Journal of computer assisted tomography 20(4), 656–665 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Thompson PM, Giedd JN, Woods RP, MacDonald D, Evans AC, and Toga AW, “Growth patterns in the developing brain detected by using continuum mechanical tensor maps,” Nature 404(6774), 190–193 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Woods RP, “Characterizing volume and surface deformations in an atlas framework: theory, applications, and implementation,” NeuroImage 18(3), 769–788 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Chung MK, Dalton KM, and Davidson RJ, “Tensor-based cortical surface morphometry via weighted spherical harmonic representation,” IEEE transactions on medical imaging 27(8), 1143–1151 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Meinshausen N. and Bühlmann P, “Stability selection,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 72(4), 417–473 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- [11].Boyd S, Parikh N, and Chu E, [Distributed optimization and statistical learning via the alternating direction method of multipliers], Now Publishers Inc; (2011). [Google Scholar]

- [12].Navitsky M, Joshi AD, Kennedy I, Klunk WE, Rowe CC, Wong DF, Pontecorvo MJ, Mintun MA, and Devous MD Sr, “Standardization of amyloid quantitation with florbetapir standardized uptake value ratios to the centiloid scale,” Alzheimer’s & Dementia 14(12), 1565–1571 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yuan M. and Lin Y, “Model selection and estimation in regression with grouped variables,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology) 68(1), 49–67 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- [14].Qin Z, Scheinberg K, and Goldfarb D, “Efficient block-coordinate descent algorithms for the group lasso,” Mathematical Programming Computation 5(2), 143–169 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [15].Li Q, Yang T, Zhan L, Hibar DP, Jahanshad N, Wang Y, Ye J, Thompson PM, and Wang J, “Large-scale collaborative imaging genetics studies of risk genetic factors for Alzheimer’s disease across multiple institutions,” in [International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention], 335–343, Springer; (2016). [Google Scholar]

- [16].Liu X, He J, Min W, and Yang H, “Missing information imputation for disease-dedicated social networks with heterogeneous auxiliary data,” IISE Transactions on Healthcare Systems Engineering 10(2), 87–98 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- [17].Liu X, He J, Duddy S, and O’Sullivan L, “Convolution-consistent collective matrix completion,” in [Proceedings of the 28th ACM international conference on information and knowledge management], 2209–2212 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang J, Zhou J, Wonka P, and Ye J, “Lasso screening rules via dual polytope projection,” in [Advances in neural information processing systems], 1070–1078 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- [19].Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, et al. , “Advances in functional and structural mr image analysis and implementation as fsl,” Neuroimage 23, S208–S219 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shi J, Thompson PM, Gutman B, and Wang Y, “Surface fluid registration of conformal representation: Application to detect disease burden and genetic influence on hippocampus,” NeuroImage 78, 111–134 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang Y, Song Y, Rajagopalan P, An T, Liu K, Chou Y-Y, Gutman B, Toga AW, and Thompson PM, “Surface-based TBM boosts power to detect disease effects on the brain: an N=804 ADNI study,” Neuroimage 56(4), 1993–2010 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chung MK, Robbins SM, Dalton KM, Davidson RJ, Alexander AL, and Evans AC, “Cortical thickness analysis in autism with heat kernel smoothing,” NeuroImage 25(4), 1256–1265 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shi J, Stonnington CM, Thompson PM, Chen K, Gutman B, Reschke C, Baxter LC, Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, and Wang Y, “Studying ventricular abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment with hyperbolic Ricci flow and tensor-based morphometry,” NeuroImage 104, 1–20 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tsao S, Gajawelli N, Zhou J, Shi J, Ye J, Wang Y, and Leporé N, “Feature selective temporal prediction of Alzheimer’s disease progression using hippocampus surface morphometry,” Brain and behavior 7(7), e00733 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Adler DH, Wisse LE, Ittyerah R, Pluta JB, Ding S-L, Xie L, Wang J, Kadivar S, Robinson JL, Schuck T, et al. , “Characterizing the human hippocampus in aging and Alzheimer’s disease using a computational atlas derived from ex vivo mri and histology,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(16), 4252–4257 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wu J, Zhang J, Shi J, Chen K, Caselli RJ, Reiman EM, and Wang Y, “Hippocampus morphometry study on pathology-confirmed alzheimer’s disease patients with surface multivariate morphometry statistics,” 1555–1559 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]