Abstract

Context and Aims:

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm with intermediate malignant potential. The aim of this study is to describe and compare the clinical presentation, computed tomography (CT) findings and anaplastic lymphoma kinase -1 (ALK-1) expression of IMT of the thorax in children and adults. We also sought to study the tumour behaviour after treatment on the follow-up imaging.

Materials and Method:

This is a retrospective observational study of 22 histopathologically proven cases of IMT in the thorax. The clinical parameters, CT findings, biopsy results, treatment received and follow-up were recorded. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher's exact test.

Results:

IMT of the thorax had diverse imaging appearances, presenting either as large invasive lung masses with or without calcifications or as smaller endobronchial lesions. Children commonly presented with long duration fever (P = 0.02) and large invasive lung masses (P = 0.026), whereas adults presented with long duration haemoptysis (P = 0.001) and endobronchial lesions or smaller lung parenchymal lesions. Calcifications were more common in children (P = 0.007). ALK-1 was positive in 40% of children and 18.2% of adults (P = 0.547). Endobronchial lesions showed a trend for ALK-1 negativity. Patients with bronchoscopic excision had local recurrence and patients with surgical wedge resection had metastatic brain lesions as compared to those with lobectomy and pneumonectomy (P = 0.0152). A patient with unresectable lung mass had malignant transformation to spindle cell sarcoma after 9.5 years.

Conclusions:

Thoracic IMT presents with some distinct clinical and CT findings in adults and children. The CT findings and management options have implications for prognosis. If resectable, lobectomy is a better option than wedge resection or bronchoscopic excision for preventing local recurrence and metastasis. IMT can undergo malignant transformation.

Keywords: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-1, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour, thorax

Introduction

An inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMT) is a mesenchymal neoplasm with myofibroblastic spindle cells and inflammatory infiltrates.[1] IMT has intermediate malignant potential with the chance for local recurrence and rarely, metastasis. The most known and common site of involvement is the lungs.[2] Other sites include the bowel, mesentery, liver, spleen, bladder, mediastinum, breast, bone and soft tissues. Approximately 50% of cases show anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangement (2p23).[3] It is a rare tumour with mostly single case reports or small case series described in the literature.[4,5,6,7,8] The aim of this study is to describe and compare the clinical presentation, computed tomography (CT) findings and anaplastic lymphoma kinase -1 expression (ALK-1) of IMT of the thorax in children and adults. We also sought to study the tumour behaviour after treatment on the follow-up imaging.

Materials and Method

This is a retrospective observational study of 22 histopathologically proven cases of IMT of thorax from December 2000 to December 2017 from a single institution identified through pathology database. The contrast enhanced CT at presentation was assessed for location and size of the mass, calcification, intensity of enhancement, and presence of invasion of mediastinum or pleura. The CT images were reviewed by a thoracic radiologist with more than 10 years of experience. The size of the lesion in its maximum dimension was noted. For patients with multiple lesions, only the size of the largest lesion was taken. The intensity of enhancement was reviewed subjectively as minimal to mild, moderate and intense enhancement on visual comparison with chest wall muscles. Invasion of mediastinum or pleura was considered definite, if the mass overtly extends into it. Invasion of mediastinum or pleura was considered possible, if there is more than 3 cm of contact or 180 degrees or more encasement of mediastinal vessels with no intervening plane. The age, presenting symptoms of patients, histopathology of biopsy or surgical specimens and immunohistochemistry were recorded by chart review. Treatment received and available clinical and imaging follow-up were noted to look for the presence or absence of local recurrence, transformation to sarcoma and metastasis to assess malignant potential. Patients with multiple lesions at presentation were presumed to be multifocal in origin. Subsequent presentation with a new focal lesion at a different site was considered metastatic. Our study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB#11406).

Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher's exact test (SPSS version 25) to look for the significance of the relationship between age, CT findings, clinical parameters, ALK-1 expression and malignant potential as evidenced by recurrence, sarcomatous transformation or development of metastasis on follow-up. P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The age of 22 patients in our study varied from 4 years to 47 years with a mean age of 23 years. Nine patients (41%) were children less than 18 years of age and 13 (59%) were adults ranging from 20 to 47 years. 54.5% of the patients were females.

IMT was pure lung parenchymal in 23%, lung parenchymal with mediastinal or pleural invasion in 36%, endobronchial in 27% and presumed multifocal involvement in 14%. The maximum size of the lesions varied from 1 cm to 15 cm. Calcifications were present in 32% cases. Minimal to mild enhancement was seen in 85% of cases, and the rest showed moderate enhancement. None had intense enhancement. None of our patients showed cavitation within the mass. Table 1 highlights the differences between children and adults with IMT of thorax with respect to presenting symptoms, CT findings and ALK-1 positivity. Children and adults showed statistically significant differences in presenting symptoms with 87.5% of children presenting with fever of 3 months to 2 years duration and 75% of the adults presenting with haemoptysis for a few months to one year. 50% of children and 58.3% of adults had cough. Other less common symptoms were loss of weight, fatigue, breathing difficulty, dysphagia and chest pain.

Table 1.

Presenting symptoms, CT findings and ALK -1 positivity in patients with IMT

| Parameters | Children (n=9) | Adults (n=13) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | 7 (87.5%) | 3 (25%) | 0.02 |

| Cough | 4 (50%) | 7 (58.3%) | 1.00 |

| Haemoptysis | 0 (0%) | 9 (75%) | 0.001 |

| Loss of weight and appetite | 3 (37.5%) | 3 (25.0%) | 0.642 |

| Size >7 cm | 6 (66.7%) | 2 (15.3%) | 0.026 |

| Minimal to mild enhancement | 7 (87.5%) | 10 (83.3%) | 1.000 |

| Presence of calcification | 6 (66.7%) | 1 (7.7%) | 0.007 |

| Lung mass with definite or possible mediastinal invasion or pleural invasion | 6 (66.7%) | 2 (15.3%) | 0.027 |

| ALK-1 | 2 (40%) | 2 (18.2%) | 0.547 |

*Non-available data were excluded from the analysis. Presenting symptoms of two patients were not available. Two patients had non-contrast CT study. Six patients did not have staining for ALK-1

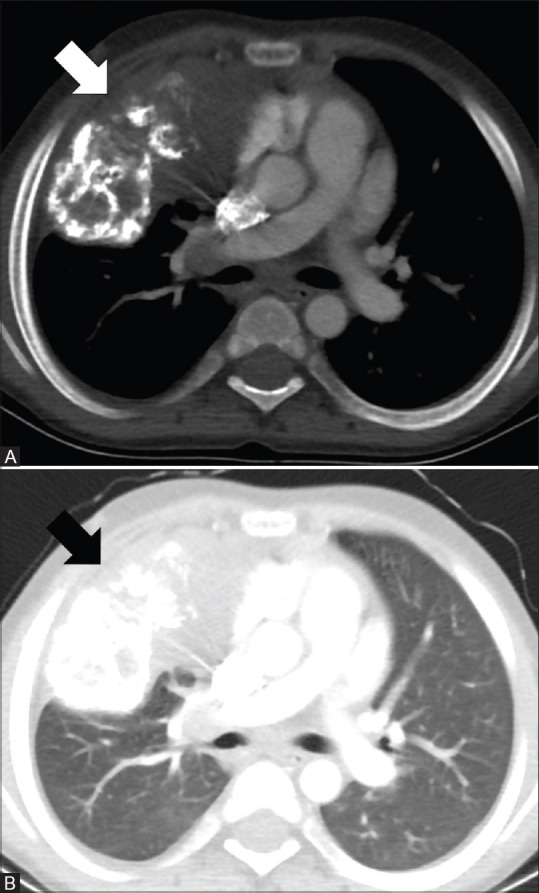

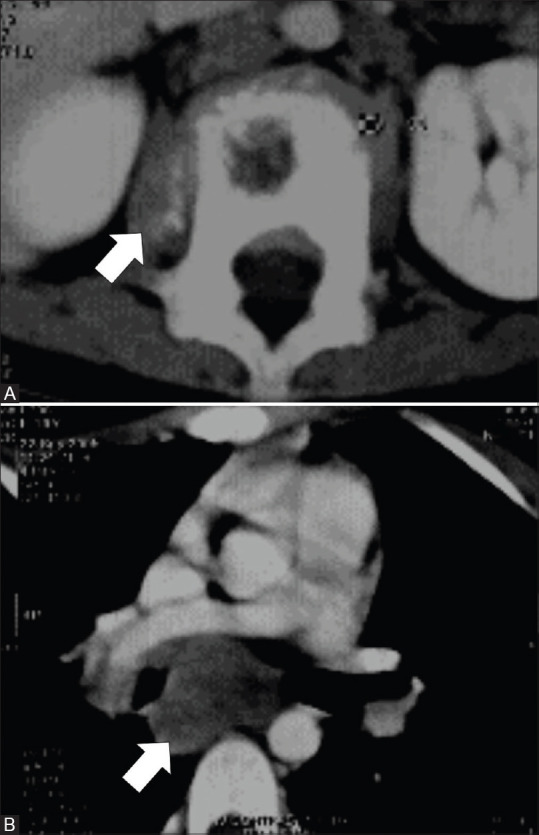

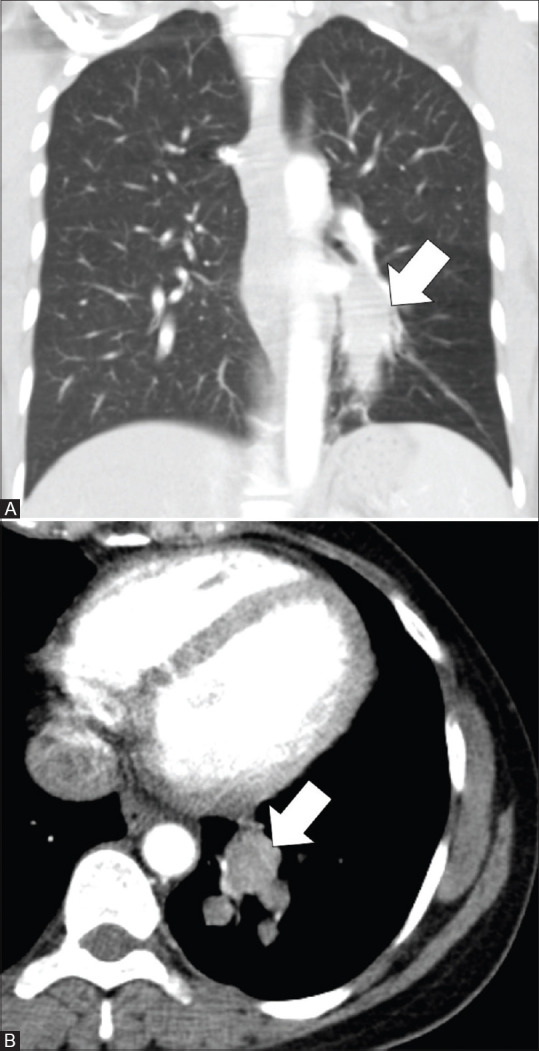

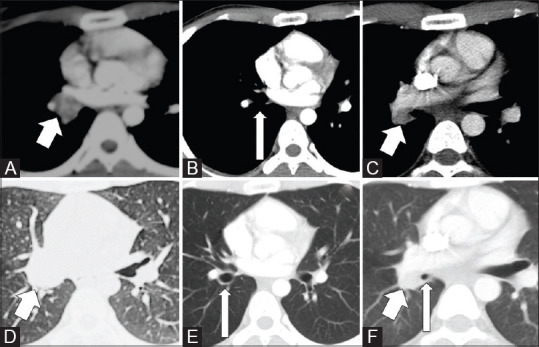

On CT, 66.7% of children had large lung masses ranging from 7 to 12 cm with definite or possible mediastinal [Figure 1] or pleural invasion and median size of 8.9 cm, whereas 69.2% of adult patients showed endobronchial lesions or lung parenchymal lesions ranging from 1 to 7 cm without mediastinal or pleural invasion and median size of 4.0 cm. There was no predilection for any lobe or bronchus. A child had a small endobronchial lesion similar to adults and another child had presumed multifocal involvement with lytic vertebral lesion and enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes [Figure 2]. 38.5% of the adults had well-defined round, ovoid or branching endobronchial lesions [Figure 3] and 30.8% of adults had single well-defined pure lung parenchymal lesions ranging from 1 to 7 cm in size. A 23-year-old patient had a 15 cm lung mass with extensive calcifications similar to childhood presentation. Two adult patients (15.4%) had presumed multifocal involvement, one with simultaneous masses in the lungs and liver and the other with bilateral multiple lung masses. Calcifications were present in 77.8% of children [Figures 1A and 2A] and 15.4% of adults and the difference was statistically significant (P = 0.007). Calcifications were absent in endobronchial lesions and lung parenchymal masses less than 7 cm. Clusters of chunky nodular and irregular ring like calcifications were seen in the masses which displayed calcification.

Figure 1(A and B).

CT images of a 10-year-old male with IMT. Axial images in mediastinal and lung window (A and B) show a large soft tissue mass with extensive calcifications in the right lung (arrows) with possible mediastinal invasion

Figure 2(A and B).

CT images of a 10-year-old female with presumed multifocal IMT of the mediastinal lymph nodes and L1 vertebra. Axial image (A) show lytic lesion in L1 vertebra with adjacent paravertebral soft tissue component showing foci of calcifications (arrow). Axial image (B) show subcarinal lymph nodal mass without calcification (arrow)

Figure 3(A and B).

CT images of a 37-year-old female with endobronchial IMT. Coronal image in lung window (A) and axial image in mediastinal window (B) show an oblong and branching, mildly enhancing 6.3 × 2.3 cm, endobronchial mass (arrows) in the posterior basal segmental and subsegmental bronchi of left lower lobe

Diagnosis of IMT was confirmed by open biopsy in 8 cases and CT or ultrasound or bronchoscopy-guided biopsy in 11 cases. In 3 patients, information regarding the mode of the biopsy was not available. In 42% cases, initial image-guided or bronchoscopic biopsy did not reveal a definite histopathological diagnosis and, open biopsy or excision was required to arrive at the diagnosis. In a patient, a third biopsy after two inconclusive bronchoscopic biopsies yielded the diagnosis. ALK-1 was not assessed in 6 patients who presented before 2005. Children showed ALK-1 positivity in 40% and adults in 18.2% (P = 0.547) and all the 6 patients with endobronchial lesions were ALK-1 negative (P = 0.234); however, these findings were not statistically significant.

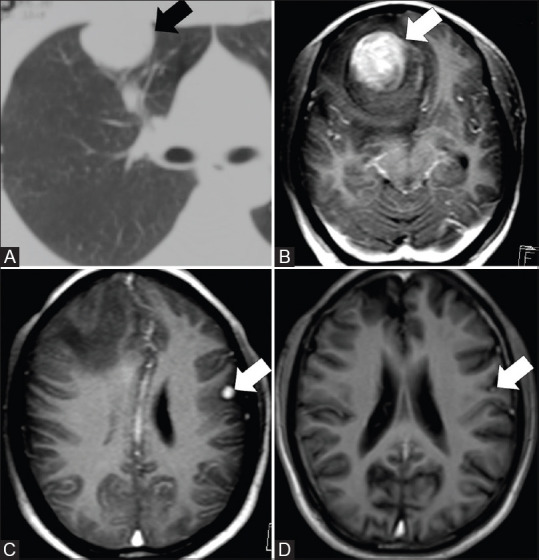

The treatment received and follow-up data are given in Table 2. Fifteen patients (68.2%) had follow up with CT thorax or chest radiograph with median follow-up of 23 months (range 6 to 114 months). Seven patients (32%) were lost to follow-up prior to initiating treatment. One adult and one child developed localising symptoms and metastatic multifocal brain parenchymal lesions [Figure 4], 6 months and 3 years, respectively after surgical excision of the lung mass. None of the patients with endobronchial tumours presented with metastasis. Three adults with endobronchial lesion and two adults with less than 7 cm lung parenchymal lesions had lobectomy with no recurrence on follow-up imaging (median 15 months). Three patients with endobronchial lesions had bronchoscopic excision of tumour, however, two of these had local recurrence on follow-up imaging (median 18 months) [Figure 5]. Patients with bronchoscopic excision and surgical wedge resection showed significantly worse prognosis as compared to those with lobectomy and pneumonectomy (P = 0.015).

Table 2.

Treatment received and follow-up data of our patients with IMT

| Treatment | Number of patients (%) | Local recurrence/metastasis/sarcomatous transformation/increase in size of lesion on follow up |

|---|---|---|

| Bronchoscopic excision | 3 (13.6%) | 2 |

| Wedge excision | 2 (9.1%) | 2 |

| Lobectomy | 5 (22.7%) | 0 |

| Pneumonectomy | 1 (4.5%) | 0 |

| Medical management with steroids, cyclophosphamide or crizotinib | 4 (18.2%) | 1 |

| Lost to follow up | 7 (32%) | Not available |

| Total | 22 (100%) |

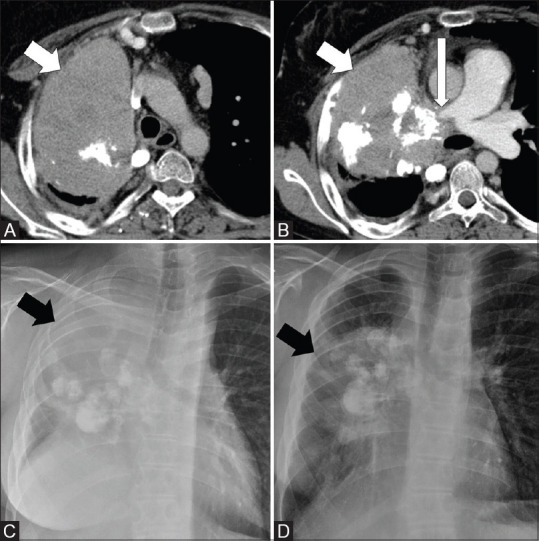

Figure 4(A-D).

CT thorax and MRI brain images of a 35-year-old male with metastases to the brain after 36 months of surgical wedge resection of IMT in the right upper lobe. Axial CT thorax (A) shows the right lung mass (arrow). Axial post contrast MRI brain images (B and C) done a few years after resection of IMT in lung showed a dominant mass in the right frontal region (arrow) and another in the left parietal region (arrow). Axial post contrast MRI brain after radiation showed reduction in size (arrow) and number of lesions (D)

Figure 5(A-F).

CT images of a 20-year-old male with recurrence of endobronchial IMT after 20 months of bronchoscopic therapeutic removal of tumour. Axial images in mediastinal (A) and lung window (D) shows the endobronchial mass (arrows) and axial images in mediastinal (B) and lung window (E) after endoscopic removal of tumour shows clear bronchus (arrows). CT thorax images after 20 months (C and F) showed recurrent tumour (short arrows) with narrowing of the bronchus (long arrow)

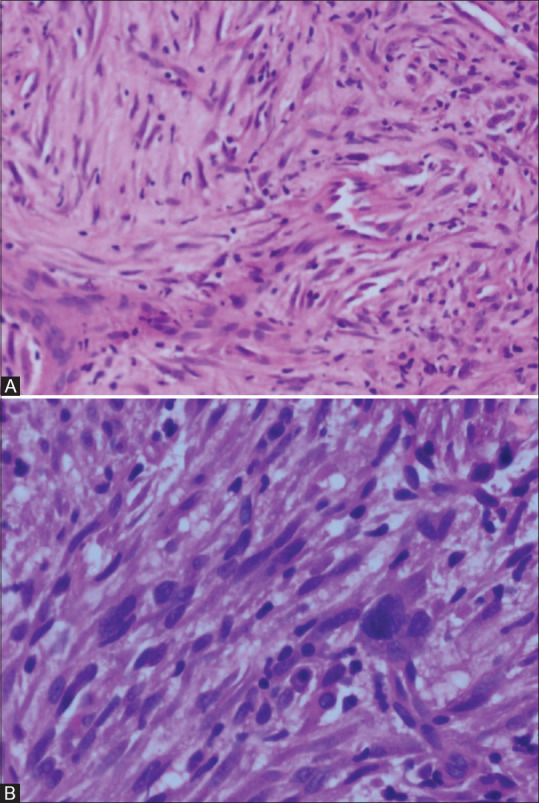

Four patients with unresectable tumours who had follow-up imaging (median 25 months) were treated with steroids. Two of these patients were additionally on cyclophosphamide. One of these patients had biopsy proven malignant transformation to high-grade spindle cell sarcoma after 9.5 years [Figure 6]. Another patient on steroids showed improvement with mild reduction in the size of the mass after 15 months and yet another patient who was ALK-1 positive had symptomatic improvement with crizotinib. Two patients did not show any change in the size of the masses on follow-up.

Figure 6(A-D).

CT images and CXR of a 23-year-old male with malignant transformation of IMT to sarcoma after 9.5 years of initial diagnosis. Axial CT thorax images (A and B) shows a large right lung mass with chunky calcifications (short arrows) infiltrating the right pulmonary artery (long arrow). CXR taken after 9.5 years showed considerable increase in size of the mass (arrow) (C) as compared to mass (arrow) at initial presentation (D). Note the elevated right hemidiaphragm in C, which is likely due to combination of infiltration of right main bronchus and phrenic nerve involvement

Discussion

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour, previously under the umbrella of the inflammatory pseudotumour, is a distinct myofibroblastic neoplasm with infiltrates of plasma cells, lymphocytes and eosinophils.[9] IMT has an incidence of 0.04% to 1% among all pulmonary neoplasms[10] and occurs mostly in children and young adults. The underlying aetiology of IMT is not certain. Various proposed causes of IMT include trauma, infection and immunological causes.[4] Patients may be asymptomatic or present with fever, haemoptysis, cough, loss of weight, dyspnoea, chest pain[5,6] or dysphagia. Haemoptysis was the commonest presentation of adults in our study unlike children who mostly presented with fever and this is similar to what is described in the literature.[11]

We observed distinct CT imaging patterns in majority of the adults and children with thoracic IMT. Young adults present with a solitary, well-defined, minimal to mildly enhancing endobronchial lesion or lung parenchymal lesion with a size of less than 7 cm, whereas children present with larger minimal to mildly enhancing lung masses more than 7 cm with definite or possible pleural or mediastinal invasion rendering them often unresectable. Calcifications are reported more commonly in children than adults occurring in 15% to 29%.[7,8] Although cavitation was not present in our series, it can be rarely seen in IMT.[7] Multifocal involvement can be seen in 5% of patients.[12]

Depending on the age and CT findings, IMT may resemble other benign or malignant lesions. Endobronchial IMT can mimic carcinoid tumours; however, IMT shows less intense enhancement, unlike carcinoid tumours. Atypical carcinoids and a few typical carcinoids can have mild to moderate enhancement similar to IMT and hence the diagnosis of carcinoid cannot be excluded on the basis of enhancement.[13] Carcinomas such as mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma and bronchogenic carcinoma should also be considered in the differential diagnosis, when the location is endobronchial. CT is helpful in differentiating mucus plugging from tumour as it is non-enhancing and usually fluid density.[13] Solitary lung mass and multiple lung lesions in young adults can resemble lymphoma, carcinoma, infection and IgG4 disease. Large masses with lung parenchymal involvement and chunky calcifications seen commonly in children may resemble hamartoma, sarcoma and metastasis such as osteosarcoma metastasis. Pleuropulmonary blastoma is another differential consideration of IMT in a child presenting with a large lung mass, especially if less than 6 years of age.[14,15] Type 1 and type 2 pleuropulmonary blastomas are cystic or solid-cystic, unlike IMT. Type 3 pleuropulmonary blastomas, which are solid tumours with areas of haemorrhage and necrosis can resemble IMT.[14] Calcifications are usually absent in type 3 pleuropulmonary blastoma, although small foci of peripheral calcifications have been reported.[15] Multisite involvement with lytic bone lesions, calcifications and lymphadenopathy can mimic tuberculosis. Hence, histopathology is essential for diagnosis, although the possibility of IMT can be considered on CT. Open biopsy may be required for diagnosis in approximately one-third to one-half of patients as image-guided or bronchoscopy-guided biopsy may not reveal the diagnosis.

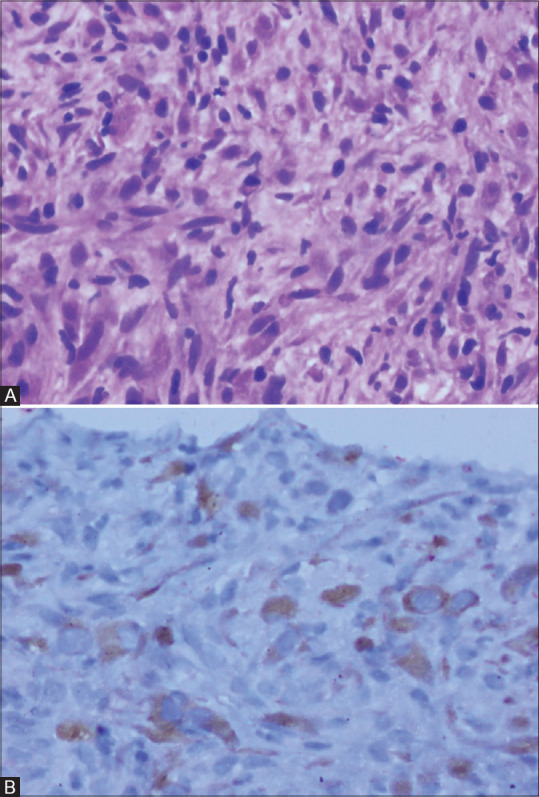

The classical cases in this study were tumours containing loosely arranged or compact fascicles of spindle cells in an oedematous or collagenous background with admixed moderate to dense infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells [Figure 7A]. Cytoplasmic reactivity for ALK-1 was seen in about 50% to 60% of cases [Figure 7B]. Though definite histological features, tumour size or cellularity are not reliable prognostic indicators, ALK-1 negative cases are known to have a higher likelihood of metastasis.[8,16] One patient in our study with metastatic brain lesions was ALK-1 negative. The other patient with brain metastasis was not tested for ALK-1. In our cases, ALK-1 positivity was more common in children with large infiltrating lung mass, and all the endobronchial lesions were ALK -1 negative; however, the results were not statistically significant. Siminovich et al. studied eight paediatric patients with pulmonary IMT and found that all were ALK-1 negative by the traditional method. However, one case showed ALK locus rearrangement by fluorescence in situ hybridization.[17] Larger sample size is required to evaluate the association of ALK-1 status with tumour morphology and behaviour, which is difficult to obtain due to the rare nature of the disease.

Figure 7(A and B).

Photomicrographs of histopathology and immunohistochemical staining for ALK-1 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour. Spindle cells with mild pleomorphism admixed with lymphocytes and plasma cells in a collagenised background (H and E 200×) (A). Granular cytoplasmic staining for ALK-1 in the spindle cells (200×) (B)

The treatment for IMT depends on the location and extent of disease. Complete surgical excision is the recommended treatment, which gives long-term survival benefits. Our follow-up data suggests that whenever mass is resectable, lobectomy and pneumonectomy are better options than wedge resection or endobronchial resection for preventing local recurrence and metastasis. The mass may be unresectable due to invasion of adjacent structures or multifocal involvement. Corticosteroids may be of some benefit in unresectable tumours as in one patient of our study. Chemotherapeutic drugs have been found to be of little use. If ALK-1 positive, crizotinib, an ALK inhibitor has been documented to be effective.[18] Radiation also has been used.[19] One of our patients who presented 3 years later with multiple brain metastases after wedge resection of the lung mass, had excision of the dominant right frontal mass and received whole brain radiation therapy for other smaller focal brain lesions. At 7-year follow-up, the patient showed a reduction in size and number of the non-resected focal brain lesions [Figure 4C and D]. Jehangir et al. suggested that patients with IMT in the lungs should be screened for brain lesions even if asymptomatic.[20] In our study, 12.5% of cases with follow-up data developed brain metastasis. Very rarely, IMT may show sarcomatous transformation, as in one patient of our study [Figure 8]. The malignant transformation showed markedly atypical cells with hyperchromatic to smudged nuclei, increased proliferative rate, atypical mitotic figures and necrosis [Figure 8B]. The underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms are still unclear. The rare possibility of biphasic tumour composed of classic IMT juxtaposed to a high-grade sarcoma in the primary site and classic IMT in the metastasis is also known.[21]

Figure 8(A and B).

Photomicrographs of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour with sarcomatous transformation. Spindle cells display moderate hyperchromasia and pleomorphism in initial biopsy (H and E 200×) (A). Marked atypia with hyperchromasia and mitosis - sarcomatous transformation in biopsy of the same mass after 9.5 years (H and E 400×) (B)

There are many limitations in this study. The initial contrast enhanced CT scan was performed outside our institution in most of the cases and only limited images in the provided film were available for interpretation. ALK -1 was not assessed in one-fourth of our patients. The sample size was small; however, this is expected given the rarity of the disease. Although the majority of patients had follow-up imaging, the duration and modes of follow up imaging were different based on the presence or absence of new symptoms and the treating clinician's decision.

Conclusions

Thoracic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours have distinct presenting symptoms and CT findings in children and adults. Wedge resection of the lung lesion and bronchoscopic removal of endobronchial lesions are associated with a higher chance of recurrence and metastasis compared to lobectomy and pneumonectomy when the lesion is resectable. IMT can present with multifocal lesions with lung, liver, bone and lymph nodal involvement. Metastatic brain lesions and malignant transformation can occur in IMT. Corticosteroids and crizotinib may be of some benefit in unresectable tumours. Studies with larger sample size and longer follow-up are needed to establish the natural history of the disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mrs. Reka K M. Sc, Department of Biostatistics, Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, for helping with the statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Zhu L, Li J, Liu C, Ding W, Lin F, Guo C, et al. Pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor versus IgG4- related inflammatory pseudotumor: Differential diagnosis based on a case series. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:598–609. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.02.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang W, Zhou X, Xu S, Lin S. CT manifestations of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (inflammatory pseudotumors) of the urinary system. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206:1149–55. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Butrynski JE, D’Adamo DR, Hornick JL, Dal Cin P, Antonescu CR, Jhanwar SC, et al. Crizotinib in ALK-rearranged inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahale A, Venugopal A, Acharya V, Kishore M, Shanmuganathan A, Dhungel K. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of lung (Pseudotumor of the lung) Ind J Radiol Imag. 2006;16:207–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carvalho A, Correia R, Fernandes MS, Pinheiro J, Leitão P, Padrão E, et al. Pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor: Report of 2 cases with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiol Case Rep. 2017;12:251–56. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda S, Onishi Y, Kawamura T, Maeda H. Clinical spectrum of pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Sur. 2008;7:629–33. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2007.173476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camela F, Gallucci M, di Palmo E, Cazzato S, Lima M, Ricci G, et al. Pulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in children: A case report and brief review of literature. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:35. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van den Heuvel DA, Keijsers RG, Van Es HW, Bootsma GP, de Bruin PC, Schramel FM, et al. Invasive inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:923–6. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a76e28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ufuk F, Herek D, Karabulut N. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung: Unusual imaging findings of three cases. Pol J Radiol. 2015;80:479–82. doi: 10.12659/PJR.894902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn P, Mertens F. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. pp. 83–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Surabhi VR, Chua S, Patel RP, Takahashi N, Lalwani N, Prasad SR. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors: Current update. Radiol Clin North Am. 2016;54:553–63. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narla LD, Newman B, Spottswood SS, Narla S, Kolli R. Inflammatory pseudotumour. Radiographics. 2003;23:719–29. doi: 10.1148/rg.233025073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeung M, Gasser B, Gangi A, Charneau D, Ducroq X, Kessler R, Quoix E, et al. Bronchial carcinoid tumors of the thorax: Spectrum of radiologic findings. Radiographics. 2002;22:351–65. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.2.g02mr01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan AA, El-Borai AK, Alnoaiji M. Pleuropulmonary blastoma: A case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Pathol 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/509086. 509086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cobanoglu N, Alicioglu B, Toker A, Galip N, Bassullu N, Dogusoy GB. Radiologic diagnosis of a type-iii pleuropulmonary blastoma. JBR–BTR. 2014;97:353–5. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang YH, Cheng B, Ge MH, Cheng Y, Zhang G. Comparison of the clinical and immunohistochemical features, including anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and p53, in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumours. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:867–77. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siminovich M, Galluzzo L, López J, Lubieniecki F, de Davila MT. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung in children: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) expression and clinico-pathological correlation. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2012;15:179–86. doi: 10.2350/11-10-1105-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Panagiotopoulos N, Patrini D, Gvinianidze L, Woo WL, Borg E, Lawrence D. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour of the lung: A reactive lesion or a true neoplasm? J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:908–11. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.04.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pavithran K, Manoj P, Vidhyadharan G, Shanmughasundaram P. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung: Unusual imaging findings. World J Nucl Med. 2013;12:126–8. doi: 10.4103/1450-1147.136739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jehangir M, Jang A, Ur Rehman I, Mamoon N. Synchronous inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor in lung and brain: A case report and review of literature. Cureus. 2017;9:e1183. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marino-Enriquez A, Wang WL, Roy A, Lopez-Terrada D, Lazar AJF, Fletcher CDM, et al. Epithelioid inflammatory myofibroblastic sarcoma: An aggressive intra-abdominal variant of inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor with nuclear membrane or perinuclear ALK. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:135–44. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318200cfd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]