Abstract

Purpose:

Pial arteriovenous fistulae (PAVF) are rare intracranial vascular malformations, predominantly seen in children and distinct from arteriovenous malformations and dural arteriovenous fistulae. PAVF often leads to high morbidity and mortality. The aim of our study was to describe the clinical features and endovascular management of PAVF at various intracranial locations; to analyze the use of liquid embolic agents and coils alone or in combination in the treatment of PAVF and to analyze the outcome of embolization.

Materials and Methods:

Retrospective review of diagnostic angiography and neurointerventional database of our institution identified a cohort of 15 patients with non-galenic PAVF from 2008 to 2014 out of 6750 patients. Fourteen patients were treated endovascularly with coils and liquid embolic materials in combination or alone. Patients were followed up for evaluation of prognosis.

Results:

Age of the patients ranged from 3 to 37 years. Most patients were male and most common presentation was headache followed by seizure. Most common location of fistula was frontal lobe. The most common type was single artery single hole fistula with venous varix. Satisfactory obliteration was seen in all cases. One patient developed intraparenchymal hematoma on the first post procedural day and outcome was poor.

Conclusions:

PAVF are rare intracranial vascular malformations which can effectively be managed endovascularly with liquid embolic, coils alone, or in combination. Complete occlusion of the fistula can be achieved in most cases in a single sitting with a reasonable morbidity related to the procedure, compared with the natural history of this disease.

Keywords: Embolization, intracranial, pial arteriovenous fistulae

Introduction

Intracranial pial arteriovenous fistula (PAVF) also known as nongalenic pial arteriovenous fistula is a rare vascular malformation where one or more pial arteries feeds directly into a cortical vein without any intervening nidus. The incidence and prevalence of PAVF in general population are unknown.[1] It accounts for 1.6% of all intracranial vascular malformations.[2] Approximately, 170 cases of pial arteriovenous fistulae have been reported since 1970.

Brain arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are abnormal connections between arteries and veins via a cluster of abnormal network of vessels called nidus embedded in brain parenchyma with lack of a true capillary bed.[3] PAVF are abnormal direct communication or shunting between pial arteries that would normally supply the brain tissue and veins that normally drain the brain, without any intervening network. In a dural AVF there is abnormal shunting between dural vessels that normally would not supply the brain tissue and veins that normally drain the brain.

PAVF consists of one or more arterial feeders and usually a single venous channel. The direct arteriovenous shunt results in high venous blood flow and varix formation with the subsequent risk of haemorrhage. PAVF can be congenital or results from iatrogenic or traumatic injury.[4] However, the exact cause remains elusive. PAVF may present with a wide range of neurologic symptoms including an asymptomatic state, headache, seizures, focal neurologic deficit to potentially catastrophic events, such as life-threatening or fatal intracranial hemorrhage. Because of the association of pial arteriovenous fistulae with a high morbidity and mortality, these lesions need to be treated in most cases.[5]

Flow disconnection either by microsurgery or endovascular means results in good outcome without the necessity of varix resection.[4] Given the deep location of these lesions or their presence in eloquent areas, surgery can be challenging.[2,6] The endovascular technique is advantageous because it is noninvasive and second the access is relatively straightforward.

The aim of our study was to describe the clinical features, angioarchitecture, endovascular management of pial arteriovenous fistulae at various intracranial locations using liquid embolic agents and coils alone and to analyze the outcome of embolization.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of a diagnostic angiography and neurointerventional database of our institution identified a cohort of 15 patients with non-galenic pial AVF from January 2008 to November 2014 out of total 6750 patients who underwent DSA at our institute. Preprocedure angiograms were reviewed. All patients had a preprocedural clinical evaluation. Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score was assessed at admission. All patients had a diagnostic angiogram prior to the embolization procedure. Fourteen patients were treated endovascularly.

Institutional ethics committee approval was obtained for the study, apart from informed consent from all the subjects or their legal guardians before the procedures.

Onyx alone was used in seven patients, coils alone in two patients, coils with onyx in two patients, NBCA (N-butyl cyanoacrylate) alone in one patient, coils with NBCA was used in two patients. Balloon assistance was taken in a single case to reduce the flow while injecting glue. Onyx 18 was used in 6 cases, whereas onyx 34 was used in one case. We used Marathon microcatheter (Covidien, EV3) for injection of NBCA and onyx, Echelon microcatheter (Covidien, ev3) for coiling. The microcatheter was positioned just proximal to the fistulous site from where the onyx or NBCA was injected.

All procedures were performed on Siemens Artis Zee (Siemens, Germany) Biplane digital subtraction angiography machine.

Patients were followed up, mRS at 3 months was assessed. After that, patients were followed up at 1 year. The outcome was categorized as neurologically excellent without any symptoms (modified Rankin Scale 0), good (modified Rankin Scale 1 or 2), and poor (modified Rankin Scale score >2).

Results

Fourteen patients were treated with endovascular means. One patient showed spontaneous obliteration of the fistula just prior to an interventional procedure. Of these, nine patients (60%) were male patients and six were female. The mean age of the treated patients was 12.5 with a range of 3 to 32 years. The mean age of all the patients was years 14 with a range of 3 to 37 years.

In our cohort, the majority of the patients (46.7%) presented in the first decade of life followed by the second decade. Only one patient had first symptoms in his 3rd decade of life. Two patients presented in the fourth decade for the first time.

In our series, the most common presenting complaint was a headache (73.3%), followed by seizure (60%), vomiting (33.3%), and episodes of loss of consciousness (33.3%), focal neurological deficits (13.3%), reduced visual acuity (13.3%). One child (6.7%) had attention deficit hyperkinetic disorder.

Seven of our patients had a history of prior intracranial hemorrhage; age group ranging from 3 to 22 years, mean age 10.1 years, median 9 years; four of them were male and three were female. All of them had single hole fistula and associated venous varix was present.

Most of the fistulas were single artery – single hole fistula – 12 out of 15 patients (80%). Three patients (20%) had more than one arterial feeders from middle cerebral artery (MCA) branches (2 patients) or from anterior cerebral artery (ACA) and MCA branches (1 patient) draining into a single venous sac in 2 patients and two separate venous sacs in one patient [Table 1]. The commonest location of the fistula was frontal lobe (33.3%) followed by temporal (26.7%) then parietal lobe (20.0%). The most common feeding artery was the MCA (46.7%), followed by ACA (26.7%). Venous drainage was superficial in 12 patients (80%) and deep in 3 patients (20%) [Table 2].

Table 1.

Topographic distribution of pial AVFs

| Frontal | Temporal | Parietal | Occipital | Posterior Fossa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-hole fistulas | 3 (20.0%) | 4 (26.7%) | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Multi-hole fistulas | 2 (13.3%) | 0 | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 5 (33.3%) | 4 (26.7%) | 3 (20.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (6.7%) |

Table 2.

Feeding arteries and draining veins

| Arterial feeder/venous drainage | No of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| MCA | 7 (46.7) |

| PCA | 2 (13.3) |

| ACA | 4 (26.7) |

| ICA | 1 (6.7) |

| VA | 1 (6.7) |

| Superficial venous drainage | 12 (80) |

| Deep venous drainage | 3 (20) |

Fourteen fistulae were associated with large venous varices. One patient had feeding artery pseudoaneurysm. None of the lesions had feeding vessel stenosis. Angioarchitecture is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Angioarchitectural features

| Angioarchitecture | No. of cases |

|---|---|

| Venous ectasia | 11 |

| Ectatic venous pouch/false venous aneurysm/Venous varix | 14 |

| Pial venous stenosis or thrombosis | 1 |

| Dural sinus stenosis or thrombosis | 0 |

| Pial venous reflux | 13 |

| Flow related arterial aneurysm | 2 |

| Transdural supply | 2 |

| Arterial stenosis | 0 |

Complete obliteration of the pial fistulae was achieved in 12 patients (85.7%) all in single sessions [Figures 1–4]. Out of these immediate complete occlusion of the fistulae was obtained in 11 patients (78.6%) and follow up angiography showed complete obliteration of the fistula in the remaining patient.

Figure 1(A-F).

Five-year-old male. Pre-embolization angiograms - AP, lateral views (A and B) reveals right Sylvian fissure pial AVF with a feeder from MCA, draining via a single ectatic cortical vein into SSS. (C) Shows the fistula on microcatheter injection. (D and E) Shows post glue embolization - complete occlusion of fistula. 3 years follow-up DSA (F) shows no recurrence

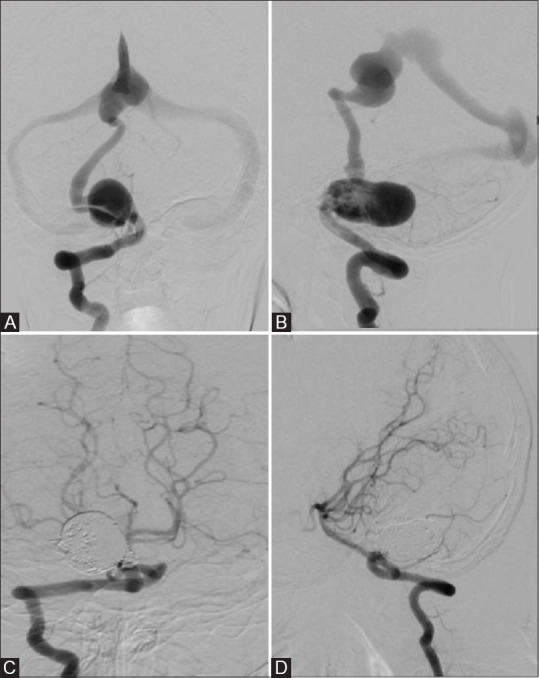

Figure 4(A-D).

)(A and B) Showing infratentorial PAVF fed by right PICA and draining via cortical vein into VOG. (C and D) Shows complete obliteration seen with the deployment of coils

Onyx alone was most commonly used embolic material (7 out of 14 patients [50%]) [Figure 3] followed by coiling alone [Figure 4] and coiling with onyx in two patients.

Figure 3(A-F).

Sixteen-year-old female. (A and B) showing slow flow fistula in left frontal region fed by a branch of ACA and draining into SSS. (C and D) showing complete obliteration of the fistula on post onyx embolization. Unsubtracted angiographic image (E) reveals onyx cast in situ. Follow-up MRA (F) after 3 months, no recurrent lesion

Spontaneous resolution encountered in one patient. A 37-year-old man presented with history of several episodes of seizure which was sudden onset in onset 4 months ago. Higher mental function, cranial nerves, motor, sensory systems were normal. DSA performed 4 months ago showed left parietal pial fistula fed by precentral, rolandic branch of left MCA draining into dilated venous sacs which in turn were draining by cortical veins to middle and posterior third of superior sagittal sinus. It was planned for onyx/glue embolization of the pial fistula. On the day of the procedure DSA showed complete obliteration of the fistula suggestive of spontaneous thrombosis otherwise normal vasculatures. Patient was discharged in stable condition without any neurological deficit.

Complications/adverse events

In one patient [Figure 5], there was migration of glue into the SSS, transverse, and sigmoid sinuses with pulmonary embolism. She developed deep venous infarcts involving bilateral thalami and pulmonary hypertension. She was managed in ICU aggressively for 15 days. However, she recovered gradually with GCS 15/15 at the time of discharge. On follow up at 12 months she was doing well without any neurological deficit. Chest radiograph showed clearing up of bilateral lung opacities. However, there was a complete obliteration of fistula and follow up mRS was 0. (Case no. 3). Follow up after 12 months no neurological deficit and improved lung functions. Another patient with a pial shunt from supraclinoid ICA with large venous varix developed 3rd nerve palsy with occasional diplopia following the procedure. Resolution of proptosis and improvement of vision was noted on 12 months follow up.

Figure 5(A-H).

Nine-year-old female. (A and B) showing Pial AVF fed by M1 perforator draining into BVOR to VOG to straight sinus. (C and D) shows coil & NBCA cast in the venous sac, BVOR; migrated NBCA in transverse sinus. (E) DWI image shows bilateral thalamic infarcts. (F) CT thorax shows glue emboli within pulmonary vasculatures, right atrium. (G) Chest X-ray shows pulmonary glue embolism. (H) Follow up Chest X-Ray after one-year showing resolution of opacities in bilateral lung fields

Mean clinical follow-up was 12.7 months (range, 4–33 months). In our study outcomes were excellent (no deficit) in 10 patients (66.7%), good (minimal deficit) in 4 patients (26.7%), poor in one patient. There was an improvement in mRS score at 3 months compared to admission scores in all but two patients. In one patient mRS score remained the same (2) and in one patient score deteriorated from 1 to 4. Treatment, outcome, follow up is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Case summary

| Case no | Treatment modality | Embolization material | Complication | Fistula occlusion | Outcome | Follow up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Embolization | Coil | - | 100% | Good | 6 |

| 2 | Embolization | Coil+onyx | - | 100% | Good | 9 |

| 3 | Embolization | Balloon + coil + glue | Glue migration into SSS, Sigmoid sinus, Pulmonary embolism, deep venous infarct | 100% | Excellent | 12 |

| 4 | Embolization | Coil | Asymptomatic percolation of onyx into right transverse sinus | 100% | Excellent | 24 |

| 5 | Embolization | Onyx | - | 100% | Excellent | 12 |

| 6 | Embolization | Coil + Glue | - | 100% | Excellent | 12 |

| 7 | Embolization | Glue | - | 100% | Good | 33 |

| 8 | Embolization | Onyx | Intraprocedural basilar artery thrombus. Retrieved. Left distal SCA territory infarct | 100% | Excellent | 12 |

| 9 | Embolization | Onyx | POD 1-Right parietal hematoma with IV extension - decompressive craniectomy | Minimal residual filling fed by ACA branch | Poor | 13 |

| 10 | Embolization | Onyx | - | 100% | Excellent | 6 |

| 11 | Embolization | Coil + onyx | 3rd nerve palsy, Visual acuity on right side 6/8 | 60% | Good | 12 |

| 12 | Embolization | Onyx | - | 100% | Excellent | 12 |

| 13 | Embolization | Onyx | - | 100% | Excellent | 24 |

| 14 | Embolization | Onyx | - | 100% | Excellent | 12 |

| 15 | Spontaneous | - | - | 100% | Excellent | 12 |

Discussion

A retrospective review of a diagnostic angiography and neurointerventional database of our institution identified a cohort of 15 patients with non-galenic pial AVF from in 7 years out of 6750 patients which were 0.22% of our diagnostic and therapeutic neurointerventional procedures. The exact prevalence of pial arteriovenous fistulae remains unknown due to its rarity. The estimated prevalence of pial AVF from previous studies is between 0.1/100,000 and 1/100,000 with no gender predisposition.[2,7] It accounts for 1.6% of all brain vascular malformations.[2] According to Cook et al. pial AVF represent approximately 4% of pediatric cerebral vascular malformations.[8]

In our series M:F ratio was 3:2. Most patients were male as reported in the previously published literature.[9,10] Pial AVFs are seldom seen in the first year of life. In children, they tend to present at around 3 years to 15 years of age. The majority of pial fistulas are diagnosed in the second and third decades of life.[11]

Clinical features

The most common presenting feature was a headache in our series. Other presenting features were seizures, focal neurological deficit, giddiness, vomiting, loss of consciousness, altered behavior, proptosis, decreased vision, epistaxis, jaw swelling. None of our patients was neonate or infant and neither cardiac insufficiency nor macrocrania was seen in any one of them.

The reported incidence of seizure was 23%, mental retardation 3%, neurological deficit 3% in the review by Weon et al. in 2005.[7] The leading clinical presentation in neonates is that of congestive cardiac insufficiency, while infants tend to present with macrocrania and focal neurological deficits.[1,7,12] Adolescent and adult patients tend to present with less specific symptoms, such as headaches, seizures, and focal neurological deficits.[13,14]

One patient (6.7%) presented with left jaw swelling. Angiography revealed left maxillary haemangioma fed by alveolar branches of the internal maxillary artery. None of our patients had evidence of telangiectasia on the skin or mucous membrane. One patient had a history of a few episodes of epistaxis without any positive family history. However, no genetic testing was carried out to refute or confirm the diagnosis of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) or capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation (CM-AVM) syndrome. It is to be noted that, recently Saliou et al. in a series of 43 patients with cerebrospinal pial arteriovenous fistulae found RASA1 or HHT gene mutation in 53% cases.[15]

The incidence of intracranial haemorrhage on cross-sectional imaging (CT scan or MRI) was quite high (46.7%) in our series and also most of them were children. Hetts et al. noted in their series that incidence of intracranial haemorrhage is more common in patients with single-hole fistulas as compared to those having multi-hole fistulas.[7] Wei-Hsun Yang et al. in their review of the literature found that pediatric type had a high percentage of varix and mass effect as clinical presentation while the adult type usually manifests with haemorrhage.[16]

Treatment

Obliteration of the fistulous site by microsurgery or endovascular means results in good outcome. Goel et al. has successfully treated 14 patients by direct surgery without any procedure-related complication.[17] In the available database of our institution during that period almost all patients with PAVF were treated endovascularly. The endovascular technique is advantageous because it is noninvasive and second the access is relatively straightforward.

The main goal of endovascular treatment of PAVF was to occlude the fistulous site, the feeding artery and the draining vein as close to the fistula as possible. If only the feeding artery is occluded without occluding the fistulous site there is high chance of recurrence. If the draining vein is obliterated before occlusion of the fistulous site, it will rupture. We used liquid embolic material (onyx or glue) and coils alone or in combination to achieve this goal.

Madsen et al. in the review of literature stated that majority of pediatric patients with PAVF were treated endovascularly (83.7%) rather than surgical intervention (17.0%). There has been a significant shift in management strategies with the advancement of the endovascular field. Of the 23 reports involving surgical interventions, 19 of them were reported prior to 2002.

NBCA alone was the most commonly used embolic material followed by coiling alone and combined coiling and NBCA. Notably, there were very few patients (3.5%) in the literature review whose PAVFs were embolized with onyx, which in contrast with the increasing usage of this agent for treating other cerebrovascular malformations.[10]

All our patients treated with onyx alone [Figure 3] showed complete obliteration of PAVF and all of them had excellent clinical outcomes. In the present study the traditional “ plug and push” technique of Onyx injection was used, this technique utilises intermittent injections of variable amounts of the liquid embolic after allowing a small amount of ‘reflux’ to form a proximal plug. Experimental and clinical studies have demonstrated a better degree of percolation of liquid embolics when injected through a dual lumen balloon catheter as compared to traditional method of injection after forming a proximal plug.[18,19] The disadvantage of the dual lumen balloon catheter technique is the reduced maneuverability when dealing with distal fistulae and increased risk of catheter retention.[18]

We treated two cases with coil with onyx and one patient with coil with glue [Figure 2] Initial deployment of coils allowed slowing of flow in the fistulae and allowing safe injection of the onyx and complete obliteration of the fistula. Placement of coil just proximal to the fistulous site allows reduction of flow and enabled controlled injection of liquid embolic reducing the chances of distal migration of the embolic agent.

Figure 2(A-D).

Three-year-old male. (A and B)showing right basi-frontal PAVF fed by branches of MCA and ACA and draining via cortical veins into SSS. (C and D) showing embolization with coils and NBCA resulted in complete occlusion of fistula

We used coiling alone [Figure 4] as an embolic material in two patients (14.3%) with immediate complete obliteration of fistulas. Lv et al. treated seven patients with detachable coils alone and complete obliteration was obtained in 4 patients.[9] Alurkar et al. treated two patients with coils alone with complete obliteration.[20]

Limaye et al. reported a series of five cases treated with glue.[21] With glue (NBCA) injection, feeding vessel could be occluded close to the fistulous site along with glue penetration into the exact site of fistula and penetration of glue into the proximal part of the vein. Flow guided microcatheter are easier to navigate into the distal cerebral vasculature compared to over the wire microcatheter which is required to deploy micro coils.

However, NBCA is delivered in a single injection and the percolation is very unpredictable which makes its use hazardous in inexperienced hands. Since NBCA is a liquid adhesive agent gluing of the microcatheter is a potential complication. We treated one case with NBCA alone [Figure 1] where 90% of 0.2 ml of glue was injected after placement of the microcatheter tip just proximal to the fistulous site through a branch of MCA. Complete obliteration of the pial AVF was obtained without any complication. Advantages of NBCA injection are that it is relatively cheaper than coiling or onyx embolization, it reduces the length of the procedure thereby deliver less radiation dose to the child compared to onyx. On the other hand, onyx utilization typically extends the embolization[22] and requires more fluoroscopic time.[23]

Coil embolization with balloon flow arrest has been successfully used in the treatment of single-channel high flow fistulas in the past. However, published success rates for endovascular techniques have not been impressive. In their series of 79 patients, Hoh et al. reported that the failure rate of endovascular embolization for pial AVFs was as high as 40%.[4]

Lylyk et al. recently reported endovascular occlusion of high flow pial macrofistulae in two patients successfully using pCANvas (phenox) and adenosine-induced asystole to allow a controlled injection of nBCA without venous passage.[24]

Spontaneous resolution of pial fistula is rare. The only patient in our case series presented with recent onset seizure which following intra

Complications

The most common procedure-related complication reported in the literature is new intracranial hemorrhage (12.6%), followed by the development of new neurological deficit (7.4%).[10]

In the current case series, a procedure-related major complication which resulted in poor outcome was 7.1%, a major complication with complete recovery in 7.1%, minor complication in 7.1%, asymptomatic migration of minimal liquid embolic was seen in two patients.

Following the day of intervention intracranial haemorrhage developed in one of our patients. Twelve hours postprocedure the patient developed right parietal hematoma with intraventricular extension and was managed by decompressive craniectomy and extra-ventricular drainage. It was a multi-hole fistula with more than one feeding arteries. The possible reason of hemorrhage is venous occlusion and incomplete obliteration of residual fistulous component from another feeder which could be cannulated even after several attempts. Following embolization of right MCA branch feeding the fistula, there was a minimal filling of the fistula through ACA feeder and due to delayed occlusion of draining vein, persistent filling from ACA feeder might have led to catastrophic hemorrhage. He developed left hemiparesis.

Glue migration, thalamic infarcts, pulmonary embolism occurred in one patient following deflation of balloon with complete recovery at 1 year follow up.

There is potential for DMSO toxicity but was not observed in this series.

Outcome

Spontaneous occlusion of the fistula was noted in one patient. In this study outcome was excellent in 10 patients (66.7%), good in 4 patients (26.7%), poor in one patient (6.6%). There was no procedure-related death.

Complete obliteration of the fistula was achieved in 12 out of 14 patients (85.7%) treated and downgrading of fistula was achieved in one patient (7.1%). In that case, 60-70% obliteration could be achieved after the first sitting of embolization with a significant decrease in the size of the pseudoaneurysm. On follow up at 3 months he was seizure free, having power 5/5 in all 4 limbs with the resolution of proptosis. DSA showed residual fistula but the patient did not give consent for second sitting of embolization as he was asymptomatic.

With a mean clinical follow-up of 12.7 months (range, 4–33 months), there was a significant improvement in MRS score at 3 months compared to MRS score at admission in all but two patients. In one patient MRS score remained the same (2) and in another patient score deteriorated from 1 to 4.

Procedure-related death was infrequent in the literature review (3.0%) by Madsen et al,[10] representing 4 patients who died of ICH after embolization (out of 137 patients). Majority of patients (65.4%) achieved an excellent outcome, 16.2% were noted to have a good outcome and 10.0% had a poor outcome, representing a significant neurological deficit at follow-up.[10]

Limitations of the study

Our study is a retrospective analysis of a relatively few numbers of cases; hence, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the pathogenesis, clinical progression, and optimal treatment strategy for pediatric patients with PAVF.

Conclusions

PAVF is a rare vascular malformation that leads to a high morbidity and mortality. Adequate treatment in the form of flow disconnection by endovascular means results in a good clinical outcome. Endovascular treatment with liquid embolic, coils alone or in combination is a safe, viable, and effective method. Complete occlusion of the fistula can be achieved in most cases in a single sitting with a reasonable morbidity related to the procedure, compared with the natural history of this disease.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hetts SW, Keenan K, Fullerton HJ, Fullerton HJ, Cooke DL, Amans MR, et al. Pediatric intracranial nongalenic pial arteriovenous fistulas: Clinical features, angioarchitecture, and outcomes. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:1710–9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halbach VV, Higashida RT, Hieshima GB, Hardin CW, Dowd CF, Barnwell SL. Transarterial occlusion of solitary intracerebral arteriovenous fistulas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1989;10:747–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geibprasert S, Pongpech S, Jiarakongmun P, Shroff MM, Armstrong DC, Krings T. Radiologic assessment of brain arteriovenous malformations: What clinicians need to know. Radiographics. 2010;30:483–501. doi: 10.1148/rg.302095728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoh BL, Putman CM, Budzik RF, Ogilvy CS. Surgical and endovascular flow disconnection of intracranial pial single-channel arteriovenous fistulae. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1351–63. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200112000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson PK, Nimi Y, Lasjaunias P, Berenstein A. Endovascular embolization of congenital intracranial pial arteriovenous fistulas. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 1992;2:309–17. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jabbour P, Tjoumakaris S, Chalouhi N, Randazzo C, Gonzalez LF, Dumont A, et al. Endovascular treatment of cerebral dural and pial arteriovenous fistulas. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2013;23:625–36. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weon YC, Yoshida Y, Sachet M, Mahadevan J, Alvarez H, Rodesch G, et al. Supratentorial cerebral arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) in children: Review of 41 cases with 63 non choroidal single-hole AVFs. Acta Neurochir. 2005;147:17–31. doi: 10.1007/s00701-004-0341-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooke D, Tatum J, Farid H, Dowd C, Higashida R, Halbach V. Transvenous embolization of a pediatric pial arteriovenous fistula. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012;4:e14. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2011-010028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lv X, Li Y, Jiang C, Wu Z. Endovascular treatment of brain arteriovenous fistulas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:851–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madsen PJ, Lang SS, Pisapia JM, Storm PB, Hurst RW, Heuer GG. An institutional series and literature review of pial arteriovenous fistulas in the pediatric population: Clinical article. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013;12:344–50. doi: 10.3171/2013.6.PEDS13110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berenstein A, Ortiz R, Niimi Y, Elijovich L, Fifi J, Madrid M, et al. Endovascular management of arteriovenous malformations and other intracranial arteriovenous shunts in neonates, infants, and children. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010;26:1345–58. doi: 10.1007/s00381-010-1206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vasudevan K, Spader HS, Grossberg JA, Murphy T, Jayaraman MV. Successful endovascular treatment of a holo-hemispheric cerebral arteriovenous fistula in an infant. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012;4:e26. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2011-010113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomlinson FH, Rufenacht DA, Sundt TM Jr, Nichols DA, Fode NC. Arteriovenous fistulas of the brain and the spinal cord. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:16–27. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.1.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Upchurch K, Feng L, Duckwiler GR, Frazee JG, Martin NA, Vinuela F. Nongalenic arteriovenous fistulas: History of treatment and technology. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E8. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.20.6.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saliou G, Eyries M, Iacobucci M, Knebel JF, Waill MC, Coulet F, et al. Clinical and genetic findings in children with central nervous system arteriovenous fistulas. Ann Neurol. 2017;82:972–80. doi: 10.1002/ana.25106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang WH, Lu MS, Cheng YK, Wang TC. Pial arteriovenous fistula: A review of literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2011;25:580–5. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2011.566382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goel A, Jain S, Shah A, Rai S, Gore S, Dharurkar P. Pial arteriovenous fistula: A brief review and report of 14 surgically treated cases. World Neurosurg. 2018;110:e873–81. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.11.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentric JC, Raymond J, Batista A, Salazkin I, Gevry G, Darsaut TE. Dual-lumen balloon catheters may improve liquid embolization of vascular malformations: An experimental study in swine. Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:977–81. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jagadeesan BD, Grande AW, Tummala RP. Safety and feasibility of balloon-assisted embolization with onyx of brain arteriovenous malformations revisited: Personal experience with the Scepter XC balloon microcatheter. Interv Neurol. 2018;7:439–44. doi: 10.1159/000490579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alurkar A, Karanam LS, Nayak S, Ghanta RK. Intracranial pial arteriovenous fistulae: Diagnosis and treatment techniques in pediatric patients with review of literature. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2016;6:2. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.175083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Limaye US, Siddhartha W, Shrivastav M, Anand S, Ghatge S. Case Report- Endovascular management of intracranial pial arterio-venous fistulas. Neurol India. 2004;52:87–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loh Y, Duckwiler GR. A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial of the Onyx liquid embolic system and N-butyl cyanoacrylate embolization of cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Clinical article J Neurosurg. 2010;113:733–41. doi: 10.3171/2010.3.JNS09370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velat GJ, Reavey-Cantwell JF, Sistrom C, Smullen D, Fautheree GL, Whiting J, et al. Comparison of N-butyl cyanoacrylate and onyx for the embolization of intracranial arteriovenous malformations: Analysis of fluoroscopy and procedure times. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:73–80. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000335015.83616.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lylyk P, Chudyk J, Bleise C, Serna Candel C, Aguilar Pérez M, Henkes H. Endovascular occlusion of pial arteriovenous macrofistulae, using pCANvas1 and adenosine-induced asystole to control nBCA injection. Interv Neuroradiol. 2017;23:644–9. doi: 10.1177/1591019917720921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]