Abstract

Background

Omeprazole administration is associated with changes in gastric and fecal microbiota and increased incidence of Clostridioides difficile enterocolitis in humans and dogs.

Hypothesis/Objectives

Study purpose was to assess the effect of omeprazole on gastric glandular and fecal microbiota in healthy adult horses.

Animals

Eight healthy horses stabled on straw and fed 100% haylage.

Methods

Prospective controlled study. Transendoscopic gastric glandular biopsies, gastric fluid, and fecal samples were obtained from each horse twice at a 7‐day interval before the administration of omeprazole. Samples were taken on the same horses before and after a 7‐day administration of omeprazole (4 mg/kg PO q24h). pH was assessed on fresh gastric fluid and other samples were kept at −20°C until analysis. Bacterial taxonomy profiling was obtained by V1V3 16S amplicon sequencing from feces and gastric glandular biopsies. Analysis of alpha, beta diversity, and comparison between time points were performed with MOTHUR and results were considered significant when P < .05.

Results

Gastric pH increased significantly after 7 days of omeprazole administration (P = .006). Omeprazole did not induce significant major changes in composition of fecal or gastric glandular microbiota, however, after administration, certain microbial genera became more predominant in the gastric glandular mucosa (lower Simpson's evenness, P = .05). Only the genus Clostridium sensu strictu_1 had a significant shift in the glandular gastric mucosa after omeprazole administration (P = .002). No population shifts were observed in feces.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Oral administration of omeprazole could have fewer effects in gastrointestinal microbiota in the horse compared to other species.

Keywords: biopsy, EGUS, gastric, microbiome, omeprazole, ulcers

Abbreviations

- EGUS

equine gastric ulcer syndrome

- GI

gastrointestinal

- NaCl

sodium chloride

- OTU

operational taxonomic unit

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

1. INTRODUCTION

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and other suppressors of gastric acid secretion are used extensively in both humans and animals with suspected disorders of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. 1 Omeprazole is the mainstay treatment of gastric ulcers in humans, dogs, and horses. 1 , 2 It is a potent inhibitor of gastric acid secretion, blocking the hydrogen‐potassium‐ATPase (proton pump) of gastric parietal cells, and allowing gastric pH to increase. 2 In equine practice, omeprazole is used to treat gastric ulcers and also commonly administered empirically for prevention of gastric disease, even without an established diagnosis. 3

In human patients, treatment with PPIs is associated with profound changes in the gut microbiome and increased risk of enteric infections by Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile), Salmonella spp, Shigella spp, or Campylobacter spp. 4 There is increased incidence of respiratory and hematogenous infections in those patients. 5 , 6 , 7 Proton pump inhibitor administration induces a decrease in the number of bacterial species found in fecal material of people, and this decrease is so marked that values approach those of samples from patients with C. difficile infection after only a week of treatment. 8 Modifications in intestinal microbiota occurs in dogs, where a 2‐week course of oral omeprazole altered the relative abundance of several bacterial communities throughout the GI tract. 1 There is a decrease of Helicobacter spp and an increase in other bacterial populations in gastric mucosa biopsies of healthy dogs after PPI administration. 1 Moreover, a significant increase of Lactobacillus in the duodenum is associated with a decrease in Faecalibacterium and the Bacteroides‐Prevotella‐Porphyromonas group in the fecal material of male dogs. 1

In horses, information about the effects of PPIs on the GI bacterial community is scarce. Administration of anti‐ulcer medication increased the risk of developing diarrhea and sepsis in sick foals. 9 There is not a significant effect of 1‐month omeprazole treatment (4 mg/kg PO q24h) on the composition and diversity of the fecal microbiota in adult horses. 10

In the present study, our hypothesis was that oral omeprazole, administered to healthy horses at therapeutic doses would induce a significant alteration of gastric and fecal microbiota.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Animals

Eight adult horses belonging to the university teaching herd were enrolled in the study. The group included 1 gelding and 7 mares (median age 16 years; range, 8‐17 years) from different breeds (2 Standardbreds, 4 Warmbloods, 1 Highlander, and 1 French Saddle horse). Horse's median weight was 488 kg (330‐636 kg). Animals were considered healthy on the basis of clinical history, clinical examination, and blood analysis including hematology and serum creatinine concentration measurement.

Horses were kept in stalls on straw bedding, were fed a diet of 100% haylage (square bales, 60% dry matter), provided at 1.5% of their body weight and divided into 2 meals per day. They had access to water ad libitum. For welfare reasons, horses were turned out daily on a sand paddock for about 1 hour. No medication or supplement was administered to the herd for at least 1 month before the beginning of the study. Animal handling, management, and feeding schedule was not modified for the duration of the study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the University of Liege (protocol 17‐1920).

2.2. Study design and sample collection

A prospective observational study was conducted, in which horses served as their own controls. All 8 horses were sampled twice at a 7‐day interval before administration of omeprazole (Day 0, Day 7), in order to assess normal variability of gastric and fecal microbiota (control period). The same month, on a second experimental period (administration period), horses were sampled on Day 0, then received a daily dose of 4 mg/kg omeprazole PO (Gastrogard, Merial LLC, Duluth, Georgia) for 7 consecutive days, and they were sampled again on Day 7. That resulted in a total of 4 sampling points, henceforth named as C0 (control period, Day 0), C7 (control period, Day 7), A0 (administration period, Day 0), and A7 (administration period, Day 7).

On sampling days, several procedures were performed on each horse, including full gastroscopy, transendoscopic gastric juice collection, gastric glandular biopsy, and fresh fecal sampling.

The day before sampling, horses were muzzled and fasted (withdrawal of haylage and water) for 8 to 12 hours before gastroscopy was performed. For the gastroscopy, horses were sedated with 0.01 mg/kg of detomidine (Domidine, Eurovet Animal Health B.V., Brussels, Belgium) and, if necessary, restrained with a nose twitch. After disinfection with a quaternary ammonium solution (Umonium38 Instruments, Huckert's, Wavre, Belgium), a 3‐m gastroscope (Olympus Medical System Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was rinsed with sterile sodium chloride (NaCl 0.9%) solution (Versol, Aguettant, Lyon, France), including the working channel, which was manipulated aseptically at all times. To minimize contamination risk, a dedicated operator (CC), wearing sterile gloves and surgical cap and mask, was in charge of gastric sample collection and manipulation.

Before introducing the gastroscope in the horse, the working channel was flushed with 20 mL sterile NaCl 0.9% and a 2 mL aliquot was collected by gravity and kept frozen at −20°C to assess potential contamination in case of aberrant results. Excess water was removed by flushing the channel twice with an air‐filled 20 cc sterile syringe. The scope was then passed into the stomach and a single‐use sterile endoscopic biopsy forceps was used to take biopsies (2 × 2 mm) of the gastric glandular mucosa, about 3 to 4 cm below the margo plicatus of the greater curvature, on the left side of the stomach. Sampling location was consistent between horses and sampling days. Biopsies were placed in sterile Eppendorf tubes and frozen at −20°C until microbiota analysis was performed.

Then, a sterile polytetrafluoroethylene tube (1.2 mm internal diameter, with a customized luer‐lock tip) was inserted in the working channel of the scope in order to collect gastric fluid (2 × 2 mL aliquots) for pH testing. Gastric fluid pH was tested in duplicate by means of colorimetric fast reagent strips (MColorpHast, Merck KGaA, Darmstatd, Germany).

Finally, once all gastric samples had been collected, the whole stomach (squamous, glandular, and pyloric areas) was inspected for the presence of ulcers, in a standard gastroscopy procedure. If lesions were present, they were scored following recommendations of the last equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) consensus statement. 11

Fecal samples were collected directly from the rectal ampulla or from a pile of freshly passed feces. The core of a fecal ball was sampled in order to avoid external bacterial contamination. Samples were placed in a conservation milieu (Stool DNA stabilizer, PSP Spin Stool DNA Plus Kit 00310, Invitek, Berlin, Germany) and stored at −20°C until sequencing.

During the administration period, omeprazole was administered at 4 mg/kg PO q24h for 7 consecutive days, by the same operator, 1 hour before the morning meal. The first omeprazole dose was administered immediately after the gastroscopy on Day 0, and the last dose in the morning of Day 7, between 1 and 4 hours before the sampling procedure. All horses were observed daily during the administration period for any changes in attitude, appetite, feces production, and presence of colic signs. During the control period, horses were clinically observed and handled as during the administration period with the exception of omeprazole administration and were also sampled on Day 0 and Day 7 as described above.

2.3. Bacterial DNA extraction and high‐throughput sequencing

Total bacterial DNA was extracted from the gastric biopsies with the DNEasy Blood and Tissue kit (QIAGEN Benelux BV, Antwerp, Belgium) and from the stool samples with the PSP Spin Stool DNA Plus Kit 00310 (Invitek, Berlin, Germany), following the manufacturer's recommendations.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the 16S rDNA V1‐V3 hypervariable region and library preparation were performed with the following primers (with Illumina overhand adapters), forward (50‐GAGAGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG‐30) and reverse (50‐ACCGCGGCTGCTGGCAC‐30). Each PCR product was purified with the Agencourt AMPure XP beads kit (Beckman Coulter, Pasadena, California) and submitted to a second PCR round for indexing, using the Nextera XT index primers 1 and 2. After purification, PCR products were quantified using the Quant‐IT PicoGreen (ThermoFisher Scientific; Waltham, Massachusetts) and diluted to 10 ng/μL. A final quantification of each library was performed using the KAPA SYBR FAST quantitative PCR Kit (KapaBiosystems; Wilmington, Massachusetts) before normalization, pooling and sequencing on a MiSeq sequencer using V3 reagents (Illumina; San Diego, California). Positive control using DNA from 20 defined bacterial species and a negative control (from the PCR step) were included in the sequencing run. 12

Raw amplicon sequencing libraries were submitted to NCBI database under bioproject number PRJNA555204.

2.4. Sequence analysis and 16S rDNA profiling

Sequence reads processing was performed as previously described using MOTHUR software package v141.1, 13 and VSEARCH algorithm for chimera detection. 14 A clustering distance of 0.03 was used for operational taxonomic unit (OTU) generation. 16S reference alignment and taxonomical assignment from phylum to genus were done with MOTHUR and were based upon the SILVA database (v1.32) of full‐length 16S rDNA sequences. 15

Subsample datasets were obtained and used to evaluate ecological indicators (Goods Coverage, Chao richness index, reciprocal Simpson microbial diversity, and Simpson derived evenness of the samples) and beta‐diversity (using a distance Bray‐Curtis dissimilarity matrix) using MOTHUR. When assessing ecology of a community (eg, microbial), alpha diversity measures the diversity within the community as opposed to β‐diversity which measures diversity between communities (or the same community at different time points). Richness is a measure of the number of species in the community and evenness expresses how evenly the individuals in the community are distributed over the different species (eg, presence of predominant species). The Good's coverage estimator is a method of estimating what percent of the total species of a community is represented in a sample.

2.5. Data analysis

Differences between groups (C0, C7, A0, A7) for the different ecological indices of the microbial population were assessed with ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc tests using PRISM 7 (Graphpad Software; San Diego, California). Differences were considered significant for a P‐value <.05. ROUT outlier identification method was applied to identify outliers based upon population structure value using PRISM7 with Q = 1%. Normality distribution was assessed by a Shapiro‐Walk test (PRISM7).

Beta‐diversity was visualized with a Bray‐Curtis dissimilarity matrix based nonparametric dimensional scaling (NMDS) model using vegan and vegan3d packages on R. Sample clustering and beta‐dispersion were respectively assessed on Bray‐Curtis dissimilarity matrix with analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) and homogeneity of molecular variance (HOMOVA) tests using MOTHUR (using 10 000 iterations on the rarefied table). Analysis of molecular variance determines whether the genetic diversity within 2 or more communities is greater than their pooled genetic diversity, and HOMOVA determines whether the amount of genetic diversity in each community is significantly different.

In order to analyze more precisely the dynamics of bacterial populations within the 2 periods of the study (control and administration), the population data at a genus level were transformed to generate a delta between the paired data of Day 7 and Day 0 for each horse, and this for the 2 periods. Starting from the subsample data set, a Hellinger transformation was applied to each genus population. This transformation consists of the square root of the target population (in our case the relative abundance of each genera) quotient over the sum of the populations for the sample:

where j indexes the genera, i the site/sample, and i. is the row sum for the ith sample.

Then, the delta is generated (Day 7‐0) with the transformed values for each genera within each horse. This transformation gives an index whose maximum is 1 (population at Day 7 = 100% and population at Day 0 = 0%) and the minimum −1. The more the index tends towards zero, the smaller the difference in abundance between the beginning and the end of the study period. A table of bacterial genera was obtained, which allowed comparing the evolution of the populations in the 2 periods (control period and administration period). In order to minimize the negative effects of the correction for multiple tests on a large scale, the bacterial genera whose sum of the absolute median values of the 2 groups was zero were removed from the analysis (80/385 genres analyzed). Finally, a paired 2‐way ANOVA (mixed model) with correction by Benjamini‐Hochberg's false discovery rate was applied to identify statistical differences between control and administration values.

3. RESULTS

Horses were clinically normal during the study period and no adverse response to omeprazole administration was observed. No major incidents happened during sample collection, except for 3 horses (2 in the A0 and 1 in the C0) that ate some straw from the bedding through the muzzle during the withholding of feed period. That resulted in a small amount of fairly solid content in their stomachs that precluded sampling of gastric juice for pH determination at the corresponding time point.

Initial gastroscopy (Day 0) revealed the presence of mild subclinical gastric lesions in 3 horses, including 1 horse with grade 1 squamous gastric disease (SGD), 1 horse with grade 2 SGD and 1 horse with a focal erythematous pyloric lesion. After the 7‐day period of administration of omeprazole, SGD had improved in both affected horses (1 was completely healed and the other showed grade 1 SGD). Endoscopic appearance of the pyloric lesion had not changed by the end of the administration period.

3.1. Oral omeprazole significantly increased gastric pH in healthy horses

During the control period, withholding of feed gastric pH values showed large individual variability with a mean of 3.7 at Day 0 (range, 1‐6) and 3.5 at Day 7 (range, 1‐5.5). During the administration period, mean withholding of feed gastric pH value significantly increased after 7 days of omeprazole administration (P = .006; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The box plot shows the significant increase in pH value of gastric fluid in 8 healthy horses after 7 days of administration of omeprazole (***P = .006). C0: control period, Day 0; C7: control period, Day 7; A0: administration period, Day 0; A7: administration period, Day 7. pH values were compared with ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test with alpha error: 0.05. Median bars on C0 and A7 match with the bottom and upper lines of the box, respectively

3.2. Analysis of microbial population

From 8 281 479 raw reads, we obtained 6 979 549 reads after cleaning with a median read length of 506 bp, and we had 5 060 272 reads after chimera removal. We retained 5492 reads per sample as a subsampling process to proceed with OTU binning (0.03 cutoff) for a total of 9407 OTUs. Mean sampling Good's coverage was 99.6%, with no statistical difference between groups.

3.2.1. Alpha diversity and beta diversity analysis

Microbial population ecological indices of glandular gastric samples were assessed at the genus level. After outlier screening, it was decided to exclude horse 2 from the analysis concerning 16S sequencing of the gastric glandular biopsies because of aberrant results obtained on the C7 sample (see horse 2 in Figure 2). The only statistical difference was detected on evenness, which was lower after 7 days of omeprazole administration (A7) in regard to the other groups (control period and A0). Results are shown in Figure 3.

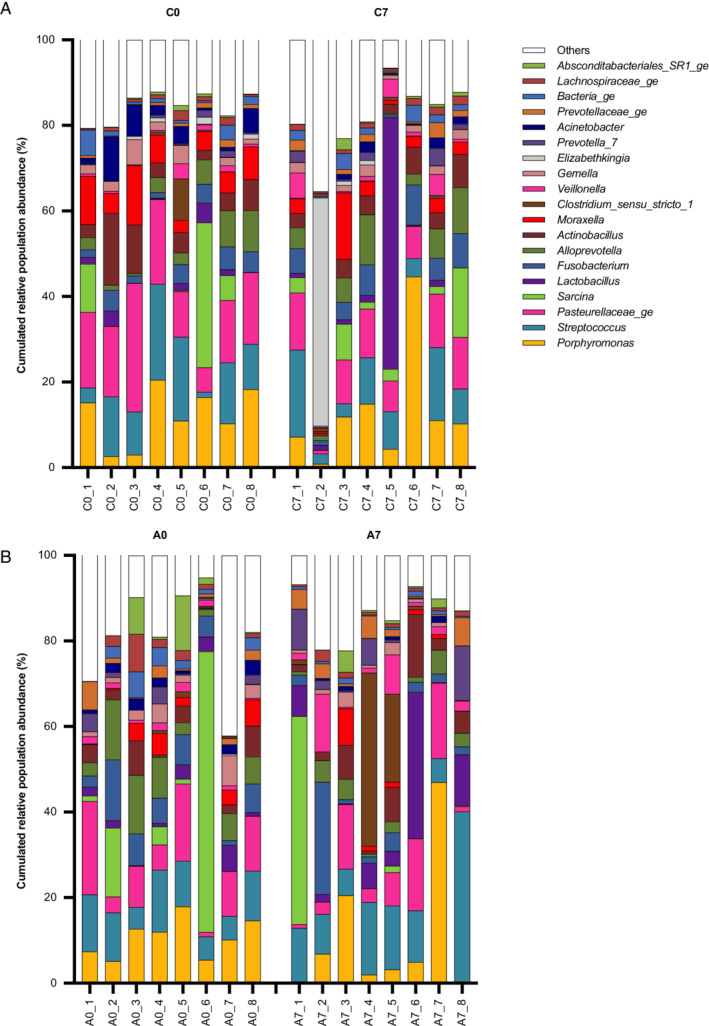

FIGURE 2.

Bar charts illustrate the 20 most abundant genera found in the glandular gastric mucosa and their cumulated relative abundance (%) in each of the 8 horses included in the study. Each bar represents a horse (1 to 8). C0: control period, Day 0; C7: control period, Day 7; A0: administration period, Day 0; A7: administration period, Day 7

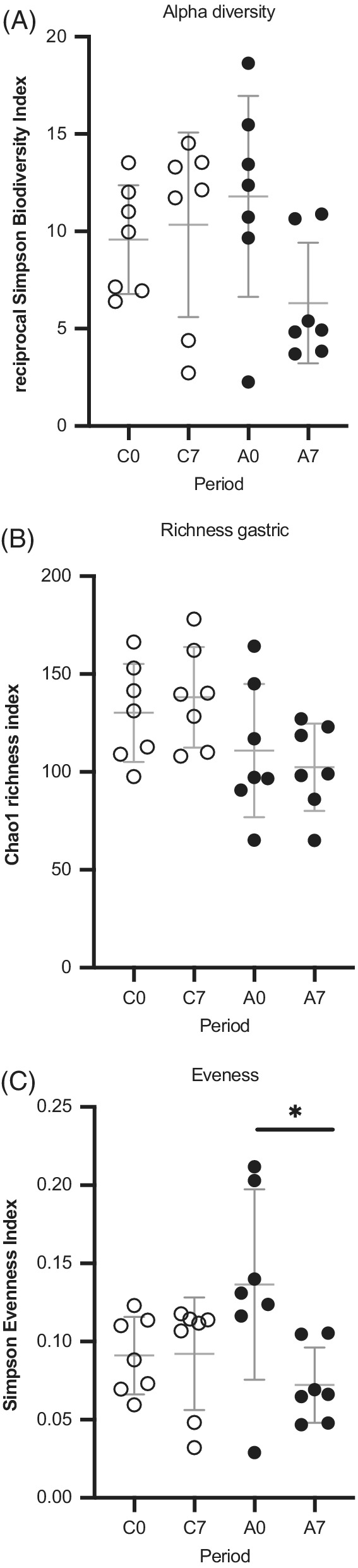

FIGURE 3.

Scatterplots depicting alpha‐diversity indices of the gastric glandular mucosa microbial population in the control (open circles) and administration (full circles) period samples: no significant difference was found between groups regarding reciprocal Simpson index or population richness. Simpson derived evenness was different between glandular gastric biopsies after 7 days of omeprazole administration in regard to Day 0 values as shown by a Wilcoxon t test (*P = .05). Horizontal lines represent the mean, and error bars indicate the 95% CIs for each group and time point. C0: control period, Day 0; C7: control period, Day 7; A0: administration period, Day 0; A7: administration period, Day 7

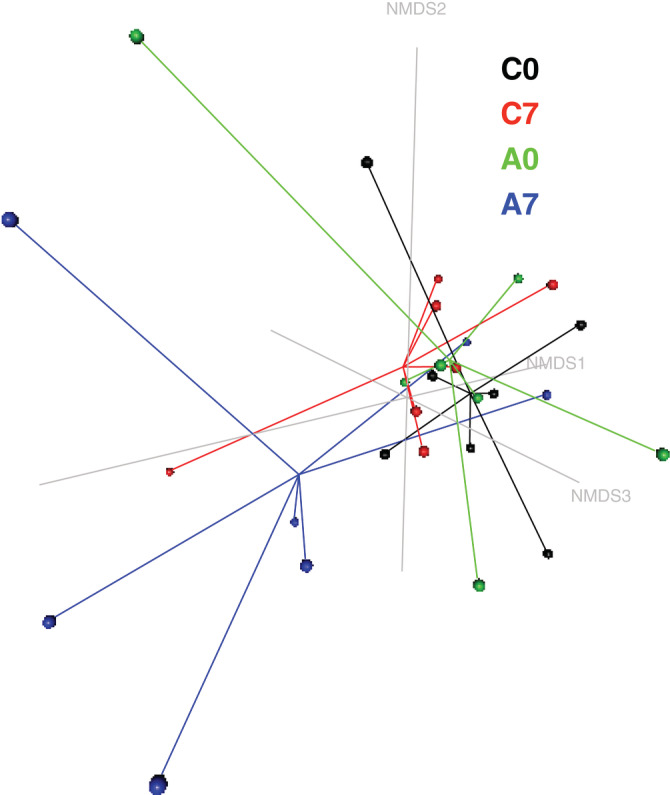

Beta diversity of gastric biopsy microbial profile was visualized using NMDS model (Figure 4). Group clustering testing did not reveal any differences between Day 7 and Day 0 within control or administration period. HOMOVA testing yielded significant results, indicating that the amount of genetic diversity in the microbiota of the glandular gastric mucosa was significantly different before and after omeprazole administration (P = .03).

FIGURE 4.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) model (k = 3, stress = 0.09) based upon a Bray‐Curtis dissimilarity matrix of the gastric glandular mucosa microbial profiles during the control and administration periods in 7 healthy horses (horse 2 was excluded because of aberrant results, probably associated with sample contamination during collection/manipulation). Samples belonging to each group are linked by lines to the centromere of the group. The community composition after 7 days of administration of omeprazole (4 mg/kg PO q24h) deviated from the composition before treatment and during the control period. C0: control period, Day 0; C7: control period, Day 7; A0: administration period, Day 0; A7: administration period, Day 7

3.2.2. Composition of equine gastric glandular microbiota

A total of 25 phyla were identified in the glandular mucosal gastric biopsies. The most abundant were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, Actinobacteria, and SR1_Abscondibacteria.

At a genus level, the most abundant defined genera observed were: Porphyromonas, Streptococcus, Sarcina, Lactobacillus, Fusobacterium, Alloprevotella, Actinobacillus, Clostridium sensu stricto_1, Veillonella, Gemella, Prevotella_7, and Acinetobacter (Figure 2).

The delta analysis of Hellinger transformed relative population abundance allowed assessment of an eventual shift in bacterial population after omeprazole administration. In the glandular gastric biopsies, Clostridium sensu strictu_1 was the only genera that showed a significant behavior in the glandular mucosa after omeprazole administration (Figure 5). No other significant differences were identified.

FIGURE 5.

A, Boxplot depicting the delta of Hellinger transformed relative abundance of bacterial genera showing statistical Clostridium sensu strictu_1 (*P = .002) differences between control (open circles) and administration (full circles) period samples. B, Scatterplot representing the relative abundance of Clostridium sensu strictu_1 in the different sampling times from control (open circles) and administration periods (full circles)

3.2.3. Alpha diversity and beta diversity analysis

The administration period had no effect on genus richness, alpha diversity or Simpson evenness of fecal samples (Figure 6). Analysis of molecular variance did not detect significant clustering of sample groups using either the Day within period or the period itself as criteria (P = .98). Again, HOMOVA testing did not yield significant differences in sample dispersion for the fecal microbiota before and after omeprazole administration (P = .98).

FIGURE 6.

Scatterplots depicting fecal population ecology of 8 healthy horses in the control (open circles) and administration (full circles) period samples: no significant differences were found in the Chao1 index (richness estimator), reciprocal Simpson index (microbial biodiversity estimator) or Simpson evenness. Horizontal lines represent the mean, and error bars indicate the 95% CIs for each group and time point. C0: control period, Day 0; C7: control period, Day 7; A0: administration period, Day 0; A7: administration period, Day 7

3.2.4. Composition of equine fecal microbiota

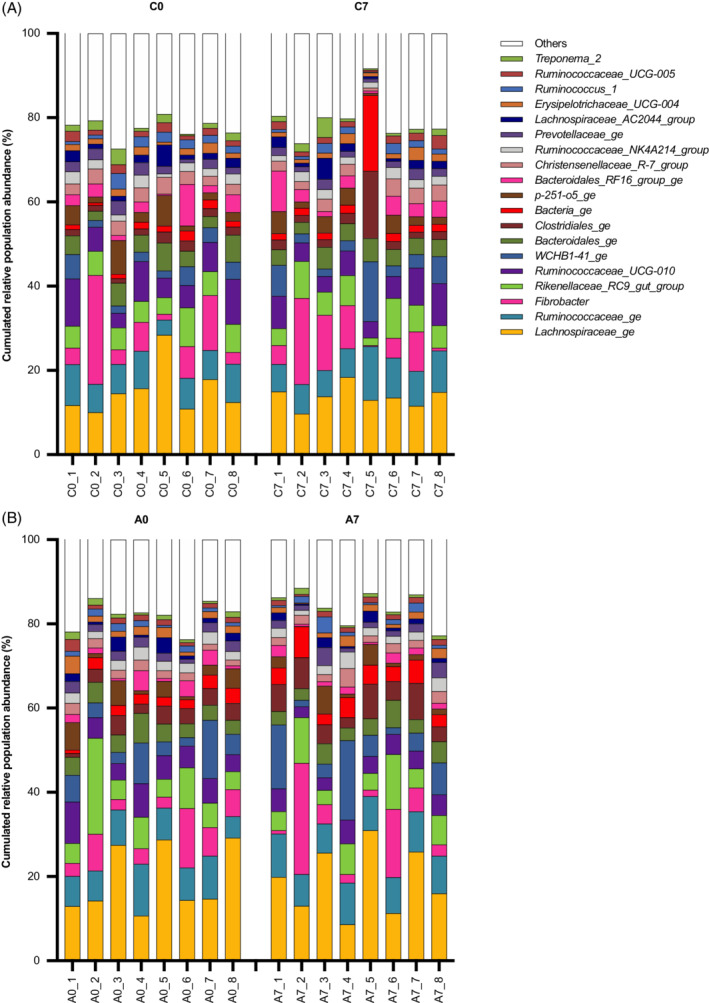

The most abundant microbial phyla found in fresh fecal material were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Verrumicrobia, and Fibrobacter. At a genus level, the most abundant genera observed during the control and administration periods are depicted in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Bar charts illustrate the 20 most abundant genera found in the feces and their cumulated relative abundance (%) in each of the 8 horses included in the study. Each bar represents a horse (1‐8). C0: control period, Day 0; C7: control period, Day 7; A0: administration period, Day 0; A7: administration period, Day 7

4. DISCUSSION

Alterations in GI microbiota occur in humans and dogs administered PPI, 1 but no similar findings had been observed so far in horses. In the present study, a 7‐day course of oral administration of omeprazole did not induce major changes in composition of fecal or gastric glandular microbiota. However, after administration of omeprazole certain microbial genera became more predominant (lower evenness) in the gastric glandular mucosa and a significant shift (increase) was observed for a specific population of Clostridia Clostridium sensu strictu_1.

Gastric microbiota has been less studied compared to fecal microbiome in horses. 10 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 Our results confirm the presence of Firmicutes, Bacteriodetes, Proteobacteria, and Fusobacteria as the major populations colonizing the mucosa of the stomach of horses, as have others. 16 Similarly to other studies, fewer species (richness) were found in the stomach compared to feces of horses, 16 and glandular mucosa microbiota had greater individual variability. There are significant differences in the bacterial communities of the stomach of horses subject to different feeding and management conditions. 19 , 22 In an attempt to minimize external factors influencing microbiota variability, we ensured that all horses enrolled in this study were exposed to the same environment and feeding management.

Certain microbial genera became more predominant (lower evenness) in the gastric glandular mucosa after omeprazole administration, and that could be the consequence of increasing the gastric juice pH. A pH rise decreases selection pressure over the gastric microbial population, allowing fast‐growing bacterial populations to proliferate. In this study, the specific bacterial populations shifting after administration of omeprazole were different among individuals, which accounts for the absence of significant results when the global microbial population before and after administration were compared. These findings suggest that the effects of omeprazole on gastric glandular microbiota, and its potential clinical consequences, are variable between horses. A larger study sample or a more prolonged course of administration might reveal significant effects or not.

A recent study explored the potential effect of omeprazole paste for 28 days on fecal and gastric microbiota in healthy adult horses. 10 Omeprazole (4 mg/kg PO q24h) did not modify the fecal microbiota, although evidence of adequate drug absorption (ie, determination of serum concentration of the drug or assessment of its effect) was not obtained. Unfortunately, the effects of omeprazole on gastric microbiota could not be properly evaluated because gastric juice samples appeared too variable within groups and over time to draw meaningful conclusions.

In the present study, gastric juice was collected to assess gastric pH, but gastric biopsies were preferred to appraise gastric microbiota. The glandular mucosa, a few centimeters below the margo plicatus, was chosen for sampling. This area was selected because it is easily available for biopsy in the stomach of a horse withheld feed and is anatomically more exposed to acidity of gastric secretion, so it was thought that changes on gastric juice pH induced by the PPI could have more dramatic effects on the local microbiota of this area compared to other localizations in the stomach. This is not the first study studying gastric microbiota through mucosal biopsies. Some human studies defend the opinion that sequencing mucosal microbiota could be a more accurate reflection of the real composition of gastric microbiota than gastric fluid, because the fluid can be easily contaminated by bacteria coming from oral cavity and esophagus that simply pass through the stomach, instead of actually colonizing it. 23 , 24 , 25 Furthermore, some bacteria such as Lactobacillus, Helicobacter, and Streptococcus are tightly adherent to the mucosal surface. 16 , 20 In the present study, a single gastric sample obtained during the control period yielded bizarre results on bacterial composition, showing a very high relative abundance of the genus Elizabethkingia, which is usually considered as a soil and water contaminant. Sample contamination during collection/manipulation was the main suspicion to explain these aberrant results. For that reason, it was decided to exclude the horse (control and administration samples) from the data analysis concerning gastric microbiota.

Results of delta analysis identified some population shifts associated with omeprazole administration. Only the genus Clostridium sensu strictu_1 had a significant shift in the glandular gastric mucosa after omeprazole administration and no population shifts were observed in fecal material. The relevance of such gastric microbiota changes is yet to be determined but the shift in the genus Clostridium sensu strictu_1 has not been correlated with a possible shift in Clostridioides difficile population. Clostridioides difficile is a potential concern because of its frequent involvement in hospital and community‐acquired diarrhea associated with variable morbidity and mortality. 26 Based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis there is a close association between Clostridioides difficile and Clostridium mangenotii, both located in the Peptostreptococcaceae family, a family that is phylogenetically far from the members of Clostridium sensu strictu. 27 This significant shift was mainly induced by 2 horses that had a massive increase in the abundance of Clostridium sensu strictu_1 after omeprazole administration (Figure 5B). The small sample size together with individual variation of gastric microbiota and its changes in response to omeprazole administration could have influenced these results.

Subclinical gastric ulceration was found during the gastroscopic examination in 3 of the 8 horses involved in this study. This was an incidental finding, although not surprising because it is well known that EGUS might have a subclinical course and variable signs. 11 It is unclear how the presence of ulcers might have influenced gastric microbiota in affected horses. It is the authors' opinion that the potential effect is probably minimal. Indeed, every gastric biopsy was performed over glandular mucosa with a healthy appearance. Moreover, most abundant bacterial populations are not different between different gastric areas (ie, from the nonglandular to glandular part) nor between ulcerated or eroded and nonulcerated regions of the equine gastric mucosa. 16 Gastric pathogens in other species, such as Helicobacter pylori, were not identified in any of the 8 horses of the present study, which is in accordance with previous studies. 10 , 18

The most abundant phyla detected in fecal samples of the horses involved in this study were Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Verrumicrobia, and Fibrobacter, as previously described. 16 , 28 Unlike in gastric samples, fecal microbiota was fairly homogenous among individuals. Fecal microbiota had a high stability over time and no significant changes in richness and diversity after omeprazole administration were observed, consistent with earlier studies. 10

Several limitations of this study must be outlined. The study involved only a small number of animals. The sample size in our study is not different from other studies conducted on microbiota in horses, 10 , 16 , 29 , 30 but larger numbers could have reduced the effect of the high individual variability observed in GI microbiota samples. For the same reason, in the present study it was decided to use each horse as its own control to assess normal variability of fecal and gastric microbiota.

Gastroscopy was performed on all horses after sedation and 12 hours withholding of feed. It is known that withholding feed from horses alters GI microbiota. 31 Amount and type of bacteria can be altered by the lack of substrate available for microorganisms and possibly by a decrease in gastric pH. 16 Unfortunately, feed withholding was mandatory for adequate sampling and objective assessment of EGUS. Three horses managed to eat some straw through the withholding of feed muzzle before gastroscopy. Nevertheless, the influence of that incident on gastric microbiota was probably minimal because horses were housed on straw during the whole study period and previous accidental or voluntary ingestion of straw was likely for all of them.

Although unlikely, mild differences in haylage microbiota could have influenced our results. Haylage was coming from the same provider throughout the study and the square bale was the same during each 7‐day sampling period. However, to overcome the bias of feeding from different square bales between the control and the administration periods, a simultaneous control group not receiving the drug could have been included in the study.

Finally, the short duration of administration was mainly dictated by financial constraints but was not considered a main issue because in humans and dogs a short course administration of omeprazole (1 and 2 weeks, respectively) is sufficient to significantly alter fecal microbiome, 1 , 8 even if more profound modifications seem to be observed with more chronic therapies (ie, of months duration). 32 Interestingly, previous studies in horses did not find a significant effect of a 4‐week administration of omeprazole in the fecal microbiota. 10

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Approved by the ethical committee of the University of Liège (Protocol 17‐1920).

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

No funding was received for this study.

Cerri S, Taminiau B, de Lusancay A‐C, et al. Effect of oral administration of omeprazole on the microbiota of the gastric glandular mucosa and feces of healthy horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34:2727–2737. 10.1111/jvim.15937

REFERENCES

- 1. Garcia‐Mazcorro JF, Suchodolski JS, Jones KR, et al. Effect of the proton pump inhibitor omeprazole on the gastrointestinal bacterial microbiota of healthy dogs. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2012;80:624‐636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zavoshti FR, Andrews FM. Therapeutics for equine gastric ulcer syndrome. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2017;33:141‐162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McClure SR, White GW, Sifferman RL, et al. Efficacy of omeprazole paste for prevention of gastric ulcers in horses in race training. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;226:1681‐1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Imhann F, Jan Bonder M, Vich Vila A, et al. Proton pump inhibitors affect the gut microbiome. Gut. 2016;65:740‐748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laheij RJ, Sturkenboom MC, Hassing RJ, Dieleman J, Stricker BH, Jansen JB. Risk of community‐acquired pneumonia and use of gastric acid‐suppressive drugs. JAMA. 2004;292:1955‐1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bavishi C, Dupont HL. Systematic review: the use of proton pump inhibitors and increased susceptibility to enteric infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1269‐1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Graham PL, Begg MD, Larson E, et al. Risk factors for late onset gram‐negative sepsis in low birth weight infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:113‐117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seto CT, Jeraldo P, Orenstein R, Chia N, DiBaise JK. Prolonged use of a proton pump inhibitor reduces microbial diversity: implications for Clostridium difficile susceptibility (erratum published in Microbiome 2016;4:10). Microbiome. 2014;2:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Furr M, Cohen ND, Axon JE, et al. Treatment with histamine‐type 2 receptor antagonists and omeprazole increase the risk of diarrhea in neonatal foals treated in intensive care units. Equine Vet J Suppl. 2012;41:80‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tyma JF, Epstein KL, Withfield‐Cargile MC, et al. Investigation of effects of omeprazole on the fecal and gastric microbiota of healthy adult horses. Am J Vet Res. 2019;80:79‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sykes BW, Hewetson M, Hepburn RJ, Luthersson N, Tamzali Y. European College of Equine Internal Medicine Consensus Statement—equine gastric ulcer syndrome in adult horses. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29:1288‐1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ngo J, Taminiau B, Fall PA, Daube G, Fontaine J. Ear canal microbiota – a comparison between healthy dogs and atopic dogs without clinical signs of otitis externa. Vet Dermatol. 2018;29:425‐e140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, et al. Introducing Mothur: open‐source, platform‐independent, community‐supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537‐7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahé F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web‐based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:590‐596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perkins GA, den Bakker HC, Burton AJ, et al. Equine stomachs harbor an abundant and diverse mucosal microbiota. J Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:2522‐2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Contreras M, Morales A, Garcia‐Amado MA, et al. Detection of helicobacter‐like DNA in the gastric mucosa of thoroughbred horses. Let Appl Microbiol. 2007;45:553‐557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Husted L, Jensen TK, Olsen SN, Mølbak L. Examination of equine glandular stomach lesions for bacteria, including Helicobacter spp by fluorescence in situ hybridization. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:84‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Costa MC, Silva G, Ramos RV, et al. Characterization and comparison of the bacterial microbiota in different gastrointestinal tract compartments in horses. Vet J. 2015;205:74‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yuki N, Shimazaki T, Kushiro A, et al. Colonization of the stratified squamous epithelium of the non‐secreting area of horse stomach by lactobacilli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:5030‐5034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ericsson AC, Johnson PJ, Lopes MA, et al. A microbiological map of the healthy equine gastrointestinal tract. PLoS One. 2016;15:1‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Fombelle A, Varloud M, Goachet AG, et al. Characterization of the microbial and biochemical profile of the different segments of the digestive tract in horses given 2 distinct diets. Anim Sci. 2003;77:293‐304. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sung J, Nayoung K, Kim J, et al. Comparison of gastric microbiota between gastric juice and mucosa by next generation sequencing method. J Cancer Prev. 2016;21:60‐65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Delgado S, Cabrera‐Rubio R, Mira A, Suárez A, Mayo B. Microbiological survey of the human gastric ecosystem using culturing and pyrosequencing methods. Microb Ecol. 2013;65:763‐772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bik EM, Eckburg PB, Gill SR, et al. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:732‐737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lawson PA, Citron DM, Tyrell KM, et al. Reclassification of Clostridium difficile as Clostridioides difficile (Hall and O'Toole 1935) Prévot 1938. Anareobe. 2016;40:95‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lawson PA, Rainey FA. Proposal to restrict the genus Clostridium Prazmowski to Clostridium butyricum and related species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015;66:1009‐1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dougal K, De la Fuente G, Harris PA, et al. Identification of a core bacterial community within the large intestine of the horse. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harlow BE, Lawence LM, Hayes SH, et al. Effect of dietary starch source and concentration on equine fecal microbiota. PLoS One. 2016;29:1‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Costa MC, Weese JS. Understanding the intestinal microbiome in health and disease. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2018;34:1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schoster A, Mosing M, Jalali M, et al. Effects of transport, fasting and anaesthesia on the faecal microbiota of healthy adult horses. Equine Vet J. 2016;48:592‐602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kwok CS, Arthur AK, Anibueze CI, Singh S, Cavallazzi R, Loke YK. Risk of Clostridium difficile infection with acid suppressing drugs and antibiotics: meta‐analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1011‐1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting Information