INTRODUCTION

Perivascular spaces (PVS), also known as Virchow-Robin spaces, are fluid-filled spaces surrounding arterioles, venules, and capillaries in the brain parenchyma1. They were originally identified and described in the 19th century2, but their function is still not well understood3. Recent evidence indicates that PVS constitute a major component of the brain clearance system, playing a critical role in the maintenance of brain health3. In fact, PVS are involved in the drainage of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the subarachnoid space and interstitial fluid from the extracellular space, contributing to the elimination of metabolic waste products from the brain4,5.

PVS can be visualized in vivo using MRI, where they appear as structures following the course of the blood vessels (arteries and veins) penetrating the cerebral parenchyma, with signal intensity similar to the CSF (i.e., dark on T1-weighted and bright on T2-weighted images) and with shape varying from linear to punctate, depending on whether the enclosed blood vessel is oriented parallel or perpendicular to the image acquisition plane, respectively. It should also be noted that PVS and enclosed blood vessels currently cannot be easily differentiated on MRI, and therefore appear as a unique tubular structure.

Although the clinical application of MRI dates back to the 1980s, only in the past two decades clinicians and researchers have started to visualize and analyze cerebral PVS on MRI (particularly at higher resolution and field strength). Such analysis of morphological features and alterations of the PVS associated with pathological conditions has been substantially facilitated by improvements to imaging sequences and post-processing techniques, which allow for enhancement of image quality and resolution. More recently, the use of ultra-high field (UHF) MRI systems (≥ 7T) have enabled even greater increases in spatial resolution due to the higher signal-to-noise ratios (SNR), resulting in significantly enhanced evaluation and visualization of PVS.

Here we describe sequences and post-processing techniques for PVS imaging, the main limitations of UHF MRI for PVS, and the latest findings regarding PVS imaged at 7T MRI.

NEUROIMAGING TECHNIQUES FOR PVS ANALYSIS

Previous MRI studies in humans have demonstrated that a higher number of visible PVS have been associated with several clinical conditions, including neuropsychiatric and sleep disorders6–10, multiple sclerosis11,12, mild traumatic brain injury13,14, Parkinson’s disease15, post-traumatic epilepsy14, myotonic dystrophy16, systemic lupus erythematosus17, cerebral small vessel disease18–22, and cerebral amyloid-β pathologies, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)23–28. These findings suggest that alterations of PVS indicate underlying cerebral pathology, and as a result, increasing attention has been dedicated to the in vivo analysis of PVS using MRI.

The PVS visible on MRI are filled with a CSF-like fluid, i.e., a fluid with a low level of proteins and macromolecules, causing PVS to predominantly exhibit T2 properties on MRI, appearing bright on T2-weighted images with long TR and TE. In fact, T2-weighted is currently considered the most appropriate sequence to visualize PVS since the contrast PVS-white matter is higher when compared to the same contrast on T1-weighted images. Turbo spin echo (TSE) sequences, such as 3D TSE-based SPACE (Sampling Perfection with Application optimized Contrasts by using different flip angle Evolutions - Siemens), or 3D fast spin echo (FSE) equivalents such as 3D T2 CUBE (GE), 3D T2 VISTA (Volume ISotropic Turbo spin echo Acquisition - Phillips), or 3D MVOX (MultiVOXel – Canon) have been shown to be particularly suitable for analyzing PVS on MRI, especially at UHF,29–32 offering isotropic or almost isotropic spatial resolution (up to 0.4 mm3) and near whole-brain coverage with a scan time of approximately 10 minutes.33

While on conventional 1.5T MRI the visibility of PVS is mostly limited to those that are dilated or tumefactive, recent advancements in sequence development and the more widespread use of high-field (3T) and UHF MRI enable improved visualization of PVS in general, not only enlarged PVS, but also normal, physiological or non-dilated PVS.

At 7T, for example, the higher SNR (more than double that achievable with a 3T MRI system) allows for an increase in spatial resolution from the reduction of voxel size. This has provided a significantly improved visualization of PVS on MRI, especially for smaller PVS (< 1 mm), and has increased the ability to study their morphological features and distribution at the mesoscale. (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Visualization and measures of PVS on MRI depend on the image resolution.

A. Axial T2-weighted 3D SPACE image at 7T from a healthy 26-year-old male volunteer acquired at 0.32 × 0.32 × 0.4 mm resolution (interpolated to 0.16 × 0.16 × 0.4mm) with the following parameters: GRAPPA=3, TR/TE=2320/299ms, flip angle=120, 2 averages. Scan time: 24 minutes. B. Manual segmentation of the PVS across a sub-portion (8 cm slab) of the white matter. C-D. Comparison of PVS segmentation at high resolution (C: 0.16 × 0.16 × 0.4 mm) and moderate resolution (D: 0.6mm3) on 7T MRI. PVS characteristics and morphologic features were overestimated when 0.6 mm3 resolution image was used, especially for the smaller PVSs. The image in D has been acquired from the same volunteer using the following parameters: GRAPPA=3, TR/TE=2140/221ms. Scan time: 11minutes.

In addition to methods for improving image acquisition, researchers have also investigated new post-processing approaches to enhance the visibility of PVS on MRI and consequently, to obtain more accurate quantitation of PVS. Various approaches for enhancing visualization of PVS have been reported in the past few years. For example, Uchiyama et al. were able to enhance the signal intensity of PVS and lacunar infarcts on T2-weighted images at 1.5 T by applying the morphological “white” top-hat transformation34. More recently, the Haar transform of non-local cubes was used to enhance the signal of PVS on T2-weighted images acquired at 7T MRI followed by a block-matching 4D filtering to suppress the noise35. Another recent work at 7T MRI described the employment of Densely Connected Deep Convolutional Neural Networks to enhance the PVS signal and to suppress the noise without the need for heuristic parameter tuning, which is required for other techniques previously described36. Finally, Sepehrband et al. have shown that an enhanced PVS contrast (EPC) image can be obtained by dividing denoised T1-weighted and T2-weighted images (Figure 2)37. This technique was developed using 3T MRI scans, but can potentially be applied to images acquired at 7T as well.

Figure 2. The PVS visibility is enhanced on EPC compared with T2-weighted images.

Example showing a T2-weighted image at 3T from a healthy young volunteer acquired at 0.7 mm3 resolution and the corresponding Enhanced PVS Contrast (EPC) image. The visibility of PVS is improved on EPC, especially in areas with small PVS and/or multiple PVS close to each other. In fact, the contrast PVS/white matter was on average higher on EPC compared with T2-weighted images.

The ultimate goal of these techniques is to facilitate the visual analysis, segmentation, and quantitation of PVS on MRI.

Since pathological changes to PVS are expected to initiate in submillimeter scales38, the use of UHF MRI and/or techniques to enhance the PVS visibility for quantitation is fundamental not only for the analysis of physiological non-dilated PVS, but also to identify the early and more subtle pathological changes occurring in PVS. The identification of these features may be found to play a critical role in the diagnosis of various diseases and can provide essential insights into the physiology and pathophysiology of the PVS, which will be important for the investigation and development of new potential therapeutic strategies for diseases associated with alterations in cerebral blood flow, CSF/lymphatic drainage and resultant changes in the PVS. In addition to structural MRI, PVS can also be studied with diffusion-weighted MRI (dMRI). Recent evidence shows that PVS significantly and systematically influences dMRI metrics when a dMRI acquisition is performed with multiple b-values (multi-shell dMRI), which allows for differentiation of the PVS fluid component from the white matter signal37. Diffusion MRI enables the study of properties of the fluid within the PVS along with the PVS microstructural changes themselves, with significant implications in terms of pathophysiology. For example, it has been demonstrated that the PVS fluid signal can predict pathological increases in mean diffusivity found in early cognitive decline38.

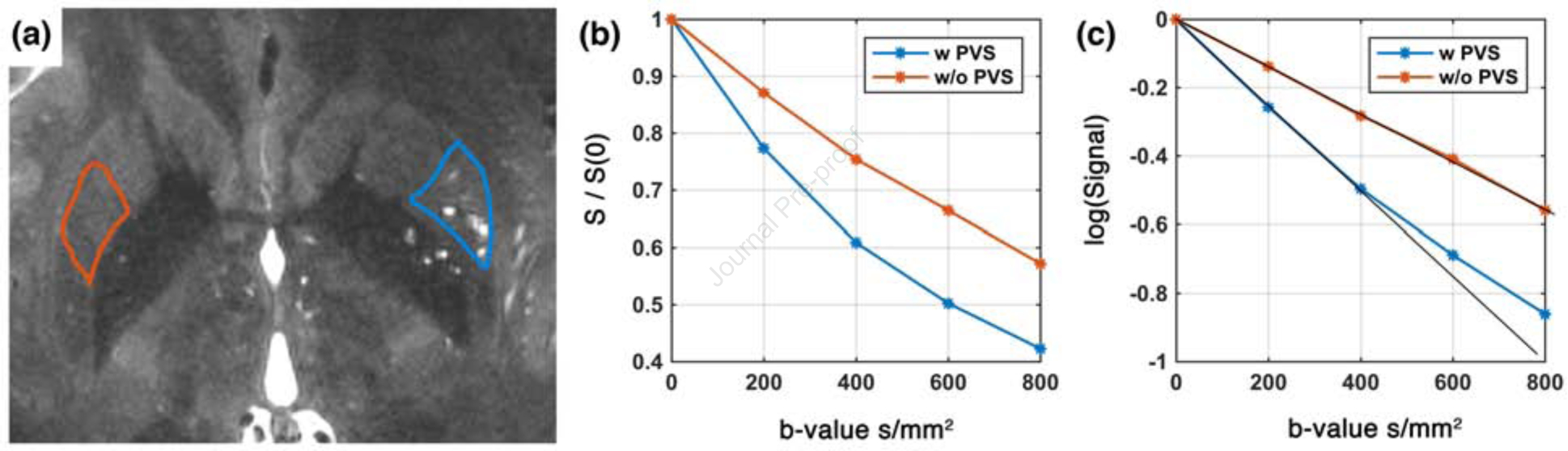

At UHF, dMRI benefits from the higher spatial resolution and reduction of partial volume effects, resulting in a more accurate separation of multiple parenchymal compartments, including fiber bundles in white matter and PVS39,41,42. PVS have been shown to have significant contributions to diffusion signal39. Unlike the highly hindered interstitial fluid of the white matter, water molecules of PVS fluid can diffuse relatively unbounded when acquiring conventional diffusion MRI data. Therefore, even a small volume fraction of the PVS fluid in the imaged voxel has a large signal contribution (high signal fraction). With high-resolution dMRI at UHF, the contribution of PVS becomes more evident in comparison with the lower field MRIs. Given the high diffusivity of PVS, its signal contribution is largest at low b-values (<1000 s/mm2). To assess the contribution of PVS to diffusion signal at UHF, we conducted a multi-shell dMRI experiment and compared diffusion signal in the same anatomical regions with and without PVS presence. A fifty-minute scan was conducted to acquire diffusion MRI volumes at the following b-values: 0, 200, 400, 600, 800 s/mm2 with fixed echo time of 65ms and TR=4400ms and isotropic resolution of 1.3 mm3. Thirty gradient-encoding directions per shell were acquired in both anterior-posterior and posterior-anterior phase encoding directions. Regions of the putamen of the basal ganglia with high vascular density were manually segmented (Figure 3. a). Basal ganglia were chosen since this region is known to have high vascular and PVS presence, allowing for comparison of PVS fluid with perfusion-related diffusion changes, also known as intra-voxel incoherent motion (IVIM)43. Experimental data showed that PVS fluid explains fast diffusion signal decay at low b-values (200 – 800 s/ mm2). The region with high PVS exhibits a faster signal decay (Figure 3. b–c). As expected, a higher proton density was also noted in the high PVS region (higher S0 signal). These results suggest that PVS fluid has a different diffusion profile in comparison with the rest of the extra-cellular fluid (i.e. interstitial fluid) and therefore should be modeled accordingly for quantitative techniques.

Figure 3. PVS fluid has significant contribution to diffusion signal at low b-value.

(a) shows the studied regions, which both have high vascular presence (lenticulostriate arteries penetrate into the putamen and have significant presence throughout). Two regions of interest with low PVS (red) and high PVS (blue) presence were manually delineated. (b-c) normalized diffusion signal and the log form in these regions are shown. Note that the region with high PVS presence decays faster and shows a bi-exponential profile.

The advantages of 7T MRI for PVS imaging are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Advantages of 7T MRI for PVS Imaging

| PVS Feature | 7T advantage |

|---|---|

| Visibility | Improved visibility at 7T |

| Count | More PVS can be counted at 7T (smaller PVS can be detected) |

| Volume | Higher accuracy at 7T (partial volume effect at lower field results in overestimation of the PVS volume) |

| Caliber | Higher accuracy at 7T (partial volume effect at lower field results in overestimation of the PVS caliber) |

| Solidity | Higher accuracy at 7T (PVS can be mapped in more depth into the parenchyma, allowing the measurement of solidity) |

| Diffusion | PVS affect diffusion signal, especially at low b-value (<1000s/mm2). |

LIMITATIONS AND DISADVANTAGES OF UHF MRI

Even though the use of UHF MRI can provide remarkable improvements in spatial resolution, SNR, and potential clinical outcomes due to its superior ability to depict small anatomical structures and identify more subtle pathology41,44,45, there are several challenges and limitations related to UHF that need to be taken into account. Here we describe the issues we consider important for PVS imaging at UHF.

Since PVS appear as relatively small structures in brain MRI scans and are distributed throughout the white matter, it is crucial to have images without artifacts that could affect the visibility and quantitation of PVS. The increased SNR of UHF MRI could certainly reduce the scan time, which is one critical factor influencing the likelihood of acquiring images with motion artifact. However, increased spatial resolution usually goes along with increased sensitivity to motion, potentially resulting in a higher incidence of artifacts caused by movement of the individual being scanned, such as blurring, ringing, and ghosting46. To a lesser extent, these artifacts can also be determined by physiological involuntary and/or spontaneous movements, including heartbeat, respiration, and minor/subtle head movements47. This issue may be significantly mitigated and often completely solved by the employment of motion correction procedures. For example, prospective motion correction systems using a camera and a moiré phase tracking marker allow identification of head movements to minute levels to dynamically adjust the imaging protocol in real time48,49. Additionally, post-acquisition procedures and deep learning methods can be used to perform a retrospective and prospective correction of involuntary microscopic head movement50. Both types of motion correction techniques will lead to improved image quality under UHF MRI51,52.

As reported above, high contrast and SNR constitute two key elements for the optimal and accurate visualization of PVS on MRI. While UHF provides higher SNR than MRI systems at lower field strength, it is important to consider that the Larmor frequency for protons in the human head increases as well, and therefore the transmit radiofrequency (RF) magnetic field (B1) results in inhomogeneity because the RF wavelength of B1 becomes smaller than anatomical structures in the main magnetic field53. The increase in B1 inhomogeneity alters the CNR and flip angles across the field of view, resulting in a progressive decrease of SNR from the central part of brain to the periphery41. B1+inhomogeneity is particularly problematic for PVS imaging because it especially affects spin-echo based sequences, including T2-weighted, due to magnetization refocusing54–58. Moreover, since the course of PVS in the white matter tends to be centripetal, extending from the subcortical white matter towards the lateral ventricles, the loss of SNR in the periphery may significantly influence the ability to detect the subcortical portion of PVS. The two most common solutions to try to alleviate the effects related to B1 inhomogeneities are the following: the employment of transmit and receive RF parallel coil arrays (parallel transmit/receive), which can model the RF pulse sequences on each channel enhancing the B1 homogeneity59, and the use of adiabatic RF pulses, which improves the outer-volume suppression by controlling and adjusting the frequency and amplitude of B1 above the adiabatic threshold60.

The next two challenges are related to the safety of the subjects undergoing the MRI scan at UHF. Specific absorption rate (SAR) is the amount of RF energy absorbed by the human body during the scan, followed by a rise in temperature. SAR not only exhibits approximately a quadratic growth with the magnetic field but is also significantly increased by the use of sequences with large and/or very rapid RF pulses, including TSE, which is commonly used for PVS imaging. In order to avoid an excessively high SAR, parallel imaging techniques, such as generalized auto-calibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA), can be used; moreover, reducing flip angles and increasing TR may be convenient to lower SAR, although it may lead to longer acquisition times. It should be noted that, for safety purposes, MRI scanners generally prevent initiation of the acquisition of images with sequences where estimated SAR is close or above the limits set by the FDA (for brain MRI: 38° C or 3.2 W/kg averaged over head mass). Finally, all individuals entering a MR environment need to be screened for biomedical implants and devices. This is particularly critical at UHF, since presently only a limited number of implants have been tested and approved for 7T MRI scanners, which precludes the use of UHF MRI in subjects with untested implants61–64. Recently, safety guidelines for healthcare professionals have been proposed in order to ensure safety in research subjects or patients with metallic implants referred for 7T scans, including those with untested implants65. In general, an accurate scrutiny of the potential risk versus benefit of the MRI exam for each individual as well as an analysis of the material, anatomical location, and type of implant are the most important aspects to consider when deciding whether or not to proceed with the scan65.

LATEST RESEARCH IN PVS AT UHF MRI

In the past few years, several groups employed 7T MRI systems to investigate PVS, both under physiological conditions and in pathology. The first study of PVS at 7T reported the feasibility of imaging and quantification of PVS at UHF and confirmed, in a small sample size, that PVS density in AD patients was significantly higher compared with age-matched healthy controls31, as previously demonstrated at lower field strength23–28. Another recent paper investigated whether PVS may represent a new biomarker for epilepsy29. The authors manually counted PVS using axial T2-weighted TSE sequences acquired in 21 patients with focal epilepsy and 17 healthy volunteers. They found that epilepsy patients presented a more asymmetric distribution of PVS; in 72% of cases, the region of maximum asymmetry matched with the suspected seizure onset zone, with less PVS visible in that area compared with the contralateral side29. The relationship between PVS asymmetry and epilepsy was interpreted as an effect of the disease on cerebral structures, possibly determined by the disrupted macrophage activity in the seizure onset zone29.

The advancements in PVS analysis on MRI have allowed for further study of PVS not only in disease but also in physiological states. To date, the normal amount and distribution of PVS in healthy human brains have not been fully described nor understood, and therefore the ability to confidently define the pathogenic alterations in PVS, especially in subclinical stages of diseases, is hindered. Recently, two groups analyzed PVS in healthy volunteers using 7T MRI. Bouvy et al. showed that PVS were spatially correlated with lenticulostriate arteries in the basal ganglia and with perforating arteries in the centrum semiovale, but not with veins32. Moreover, a higher number of PVS were found in older adults (n=5, age: 51–72 years old) compared to younger people (n=5, age: 19–27 years old), but no differences in PVS diameter were reported32. Zong et al. described the PVS morphology and distribution in the basal ganglia, thalamus, midbrain, and white matter of 45 healthy subjects (21–55 years old) scanned at 7T33. They found that PVS count and volume fraction significantly increased with age in basal ganglia and presented high inter-subject variability as well as a significant spatial heterogeneity not solely explained by B1 inhomogeneities33. Interestingly, they also showed that carbogen breathing significantly increased the PVS volume fraction in basal ganglia and white matter33, which suggests a link between vasodilation and apparent PVS volume on MRI. Further studies with larger sample size will be required to better understand the morphological features of PVS in normal conditions and which factors affect the physiological appearance of PVS on MRI.

CONCLUSION

Current results show that imaging PVS at UHF is feasible and offers the possibility of accurately identifying and quantitation of the PVS, including those smaller in size (< 1 mm) which are usually not visible on conventional lower field MRI scans. This may be particularly helpful in analyzing the normal PVS and the early pathologic alterations of PVS. More studies, both in clinical and research settings, are required to investigate the advantages of UHF for in vivo PVS analysis. This will allow further investigation into the physiological function of PVS in terms of cerebrospinal-interstitial fluid exchange, lymphatic and brain clearance system, as well as their role as a diagnostic biomarker for some neurological diseases. Moreover, further efforts are needed to solve the existing limitations of imaging at UHF, including both those related to sequence optimization and hardware development, and those concerning SAR limitations and the safety of subjects and patients. Nonetheless, the more widespread application of UHF MRI systems is expected to result in novel scientific discoveries and more opportunities to use 7T MRI scanners as diagnostic tools in clinics, with subsequent anticipated improvement of the clinical outcomes of patients.

KEY POINTS.

UHF MRI systems have higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) compared with lower field systems, resulting in improved spatial resolution and/or shorter scan times. This allows for visualization of normal and pathological structures in greater detail.

UHF MRI can be applied to image PVS in vivo, with advantages in the identification and accurate quantification of PVS.

UHF MRI presents some technical challenges and limitations relating to safety issues that must be considered.

SYNOPSIS.

The recent Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of 7T MRI scanners for clinical use has introduced the possibility to study the brain not only in physiological but also pathological conditions at ultra-high field (UHF). Since UHF MRI offers higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and spatial resolution compared with lower field clinical scanners, the benefits of UHF MRI are particularly evident for imaging small anatomical structures, such as the cerebral perivascular spaces (PVS). A few new studies performed at 7T have already shown the feasibility and the advantages of UHF for the analysis of PVS. However, UHF MR systems present some technical challenges and safety concerns that have not yet been solved, and therefore, the use of UHF MRI has some limitations that need to be taken into consideration. In this article, we describe the application of UHF MRI for the investigation of PVS, including imaging techniques, advantages and disadvantages of using 7T MRI for the analysis of PVS, and the latest research in PVS at UHF MRI.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number RF1MH123223. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The Authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Giuseppe Barisano, Neuroscience Graduate Program, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Meng Law, Department of Neuroscience, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

Rachel M. Custer, Laboratory of Neuro Imaging, Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Arthur W. Toga, Laboratory of Neuro Imaging, Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Farshid Sepehrband, Laboratory of Neuro Imaging, Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhang ET, Inman CB, Weller RO. Interrelationships of the pia mater and the perivascular (Virchow-Robin) spaces in the human cerebrum. J Anat. 1990;170:111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woollam DH, Millen JW. The perivascular spaces of the mammalian central nervous system and their relation to the perineuronal and subarachnoid spaces. J Anat. 1955;89(2):193–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wardlaw JM, Benveniste H, Nedergaard M, et al. Perivascular Spaces in the Brain: Anatomy, Physiology, and Contributions to Pathology of Brain Diseases. Vol 16 Nature Research; 2020. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-0312-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen MK, Mestre H, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):1016–1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, et al. Clearance systems in the brain—implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(8):457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacLullich AMJ, Wardlaw JM, Ferguson KJ, Starr JM, Seckl JR, Deary IJ. Enlarged perivascular spaces are associated with cognitive function in healthy elderly men. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(11):1519–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taber KH, Shaw JB, Loveland KA, Pearson DA, Lane DM, Hayman LA. Accentuated Virchow-Robin Spaces in the Centrum Semiovale in Children with Autistic Disorder. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28(2):263–268. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200403000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rollins NK, Deline C, Morriss MC. Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Dilated Virchow-Robin Spaces in Childhood. Radiology. 1993;189:53–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patankar TF, Baldwin R, Mitra D, et al. Virchow-Robin space dilatation may predict resistance to antidepressant monotherapy in elderly patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 2007;97(1–3):265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berezuk C, Ramirez J, Gao F, et al. Virchow-Robin spaces: correlations with polysomnography-derived sleep parameters. Sleep. 2015;38(6):853–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Achiron A, Faibel M. Sandlike appearance of Virchow-Robin spaces in early multiple sclerosis: A novel neuroradiologic marker. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(3):376–380. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wuerfel J, Haertle M, Waiczies H, et al. Perivascular spaces--MRI marker of inflammatory activity in the brain? Brain. 2008;131(9):2332–2340. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inglese M, Bomsztyk E, Gonen O, Mannon LJ, Grossman RI, Rusinek H. Dilated Perivascular Spaces: Hallmarks of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(4). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan D, Barisano G, Cabeen R, et al. Analytic Tools for Post-traumatic Epileptogenesis Biomarker Search in Multimodal Dataset of an Animal Model and Human Patients. Front Neuroinform. 2018;12:86. doi: 10.3389/fninf.2018.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laitinen LV, Chudy D, Tengvar M, Hariz MI, Tommy Bergenheim A. Dilated perivascular spaces in the putamen and pallidum in patients with Parkinson’s disease scheduled for pallidotomy: A comparison between MRI findings and clinical symptoms and signs. Mov Disord. 2000;15(6):1139–1144. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Costanzo A, Di Salle F, Santoro L, Bonavita V, Tedeschi G. Dilated Virchow-Robin spaces in myotonic dystrophy: Frequency, extent and significance. Eur Neurol. 2001;46(3):131–139. doi: 10.1159/000050786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyata M, Kakeda S, Iwata S, et al. Enlarged perivascular spaces are associated with the disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12966-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Potter GM, Doubal FN, Jackson CA, et al. Enlarged perivascular spaces and cerebral small vessel disease. Int J stroke. 2015;10(3):376–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouhl RPW, Van Oostenbrugge RJ, Knottnerus ILH, Staals JEA, Lodder J. Virchow-Robin spaces relate to cerebral small vessel disease severity. J Neurol. 2008;255(5):692–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohba H, Pearce L, Potter G, Benavente O. Enlarged perivascular spaces in lacunar stroke patients. The secondary prevention of small subcortical stroked (SPS3) trial. In: International Stroke Conference. Vol 43; 2012:A151. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doubal FN, MacLullich AMJ, Ferguson KJ, Dennis MS, Wardlaw JM. Enlarged perivascular spaces on MRI are a feature of cerebral small vessel disease. Stroke. 2010;41(3):450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):822–838. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70124-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charidimou A, Jaunmuktane Z, Baron J-C, et al. White matter perivascular spaces: an MRI marker in pathology-proven cerebral amyloid angiopathy? Neurology. 2014;82(1):57–62. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000438225.02729.04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Ramirez S, Pontes-Neto OM, Dumas AP, et al. Topography of dilated perivascular spaces in subjects from a memory clinic cohort. Neurology. 2013;80(17):1551–1556. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828f1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roher AE, Kuo Y-M, Esh C, et al. Cortical and leptomeningeal cerebrovascular amyloid and white matter pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Med. 2003;9(3–4):112–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramirez J, Berezuk C, McNeely AA, Scott CJM, Gao F, Black SE. Visible Virchow-Robin spaces on magnetic resonance imaging of Alzheimer’s disease patients and normal elderly from the Sunnybrook dementia study. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015;43(2):415–424. doi: 10.3233/JAD-132528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen TP, Cain J, Thomas O, Jackson A. Dilated perivascular spaces in the Basal Ganglia are a biomarker of small-vessel disease in a very elderly population with dementia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(5):893–898. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen W, Song X, Zhang Y. Assessment of the virchow-robin spaces in Alzheimer disease, mild cognitive impairment, and normal aging, using high-field MR imaging. Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(8):1490–1495. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldman RE, Rutland JW, Fields MC, et al. Quantification of perivascular spaces at 7T: A potential MRI biomarker for epilepsy. Seizure. 2018;54:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zong X, Park SH, Shen D, Lin W. Visualization of perivascular spaces in the human brain at 7T: Sequence optimization and morphology characterization. Neuroimage. 2016;125:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.10.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cai K, Wain R, Das S, et al. The Feasibility of Quantitative MRI of Perivascular Spaces at 7T. J Neurosci Methods. 2015;269:151–156. doi: 10.1177/0963721414541462.Self-Control [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bouvy WH, Biessels GJ, Kuijf HJ, Kappelle LJ, Luijten PR, Zwanenburg JJM. Visualization of perivascular spaces and perforating arteries with 7 T magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 2014;49(5):307–313. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zong X, Lian C, Jimenez J, Yamashita K, Shen D, Lin W. Morphology of perivascular spaces and enclosed blood vessels in young to middle-aged healthy adults at 7T: Dependences on age, brain region, and breathing gas. Neuroimage. 2020;218:116978. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchiyama Y, Kunieda T, Asano T, et al. Computer-aided diagnosis scheme for classification of lacunar infarcts and enlarged Virchow-Robin spaces in brain MR images. In: Proceedings of the 30th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS’08 - “Personalized Healthcare through Technology.” Vol 2008 Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc; 2008:3908–3911. doi: 10.1109/iembs.2008.4650064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou Y, Park SH, Wang Q, et al. Enhancement of perivascular spaces in 7 T MR image using Haar transform of non-local cubes and block-matching filtering. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung E, Chikontwe P, Zong X, Lin W, Shen D, Park SH. Enhancement of perivascular spaces using densely connected deep convolutional neural network. IEEE Access. 2019;7:18382–18391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sepehrband F, Barisano G, Sheikh-Bahaei N, et al. Image processing approaches to enhance perivascular space visibility and quantification using MRI. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12351. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48910-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi Y, Wardlaw JM. Update on cerebral small vessel disease : a dynamic whole-brain disease. 2016:83–92. doi: 10.1136/svn-2016-000035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sepehrband F, Cabeen RP, Choupan J, Barisano G, Law M, Toga AW. Perivascular space fluid contributes to diffusion tensor imaging changes in white matter. Neuroimage. 2019;197:243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.04.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sepehrband F, Cabeen RP, Barisano G, et al. Nonparenchymal fluid is the source of increased mean diffusivity in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagnosis, Assess Dis Monit. 2019;11:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barisano G, Sepehrband F, Ma S, Jann K, Cabeen R, Wang DJ, Toga AW, Law M. Clinical 7 T MRI: Are we there yet? A review about magnetic resonance imaging at ultra-high field. Br J Radiol. 2019. February;92(1094):20180492. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20180492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sepehrband F, O’Brien K, Barth M. A time-efficient acquisition protocol for multipurpose diffusion-weighted microstructural imaging at 7 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2017;78(6):2170–2184. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le Bihan D IVIM method measures diffusion and perfusion. Diagn Imaging (San Fr. 1990;12(6):133–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balchandani P, Naidich TP. Ultra-high-field MR neuroimaging. Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36(7):1204–1215. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trattnig S, Springer E, Bogner W, et al. Key clinical benefits of neuroimaging at 7 T. Neuroimage. November 2016. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2016.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zaitsev M, Maclaren J, Herbst M. Motion artifacts in MRI: A complex problem with many partial solutions. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42(4):887–901. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herbst M, MacLaren J, Lovell-Smith C, et al. Reproduction of motion artifacts for performance analysis of prospective motion correction in MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(1):182–190. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schulz J, Siegert T, Reimer E, et al. An embedded optical tracking system for motion-corrected magnetic resonance imaging at 7T. Magn Reson Mater Physics, Biol Med. 2012;25(6):443–453. doi: 10.1007/s10334-012-0320-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maclaren J, Armstrong BSR, Barrows RT, et al. Measurement and Correction of Microscopic Head Motion during Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain. PLoS One. 2012;7(11). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gallichan D, Marques JP, Gruetter R. Retrospective correction of involuntary microscopic head movement using highly accelerated fat image navigators (3D FatNavs) at 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75(3):1030–1039. doi: 10.1002/mrm.25670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stucht D, Danishad KA, Schulze P, Godenschweger F, Zaitsev M, Speck O. Highest resolution in vivo human brain MRI using prospective motion correction. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Federau C, Gallichan D. Motion-correction enabled ultra-high resolution in-vivo 7T-MRI of the brain. PLoS One. 2016;11(5). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ibrahim TS, Lee R, Baertlein BA, Abduljalil AM, Zhu H, Robitaille PML. Effect of RF coil excitation on field inhomogeneity at ultra high fields: A field optimized TEM resonatior. Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;19(10):1339–1347. doi: 10.1016/S0730-725X(01)00404-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poon CS, Henkelman RM. Practical T2 quantitation for clinical applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1992;2(5):541–553. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880020512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norris DG, Koopmans PJ, Boyacioǧlu R, Barth M. Power independent of number of slices (PINS) radiofrequency pulses for low-power simultaneous multislice excitation. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(5):1234–1240. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Majumdar S, Orphanoudakis SC, Gmitro A, O’Donnell M, Gore JC. Errors in the measurements of T2 using multiple-echo MRI techniques. I. Effects of radiofrequency pulse imperfections. Magn Reson Med. 1986;3(3):397–417. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910030305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vargas MI, Martelli P, Xin L, et al. Clinical Neuroimaging Using 7 T MRI: Challenges and Prospects. J Neuroimaging. 2018;28(1):5–13. doi: 10.1111/jon.12481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kraff O, Quick HH. 7T: Physics, safety, and potential clinical applications. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;46(6):1573–1589. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu Y Parallel Excitation with an Array of Transmit Coils. Magn Reson Med. 2004;51(4):775–784. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tannús A, Garwood M. Adiabatic pulses. NMR Biomed. 1997;10(8):423–434. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sammet CL, Yang X, Wassenaar PA, et al. RF-related heating assessment of extracranial neurosurgical implants at 7T. Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;31(6):1029–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Feng DX, McCauley JP, Morgan-Curtis FK, et al. Evaluation of 39 medical implants at 7.0T. Br J Radiol. 2015;88(1056):1–10. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20150633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dula AN, Virostko J, Shellock FG. Assessment of MRI issues at 7 T for 28 implants and other objects. Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(2):401–405. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shellock FG. Reference Manual for Magnetic Resonance Safety, Implants, and Devices: 2018 Edition. (Shellock FG, ed.). California: Biomedical Research Publishing Group; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barisano G, Culo B, Shellock FG, et al. 7-Tesla MRI of the brain in a research subject with bilateral, total knee replacement implants: Case report and proposed safety guidelines. Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;57:313–316. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2018.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]